Dear Editor,

Wolf’s isotopic response (WIR), first described in 1955, is defined as the occurrence of new dermatoses at a site that has already healed from a previous unrelated dermatosis. This is different from the isomorphic response (Koebner phenomenon), which is the development of the same disease on traumatized skin. Herpes zoster is a common cause of WIR; in fact WIR was labelled the “postherpetic isotopic response” because several types of cutaneous lesions have been described occurring within cleared cutaneous herpes zoster, or, less frequently, herpes simplex lesions.1 However, among the numerous dermatoses reported and discussed as manifestations of WIR, skin neoplasia has been rarely observed. Herein, we describe a case of superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) that developed at a healed herpes zoster site.

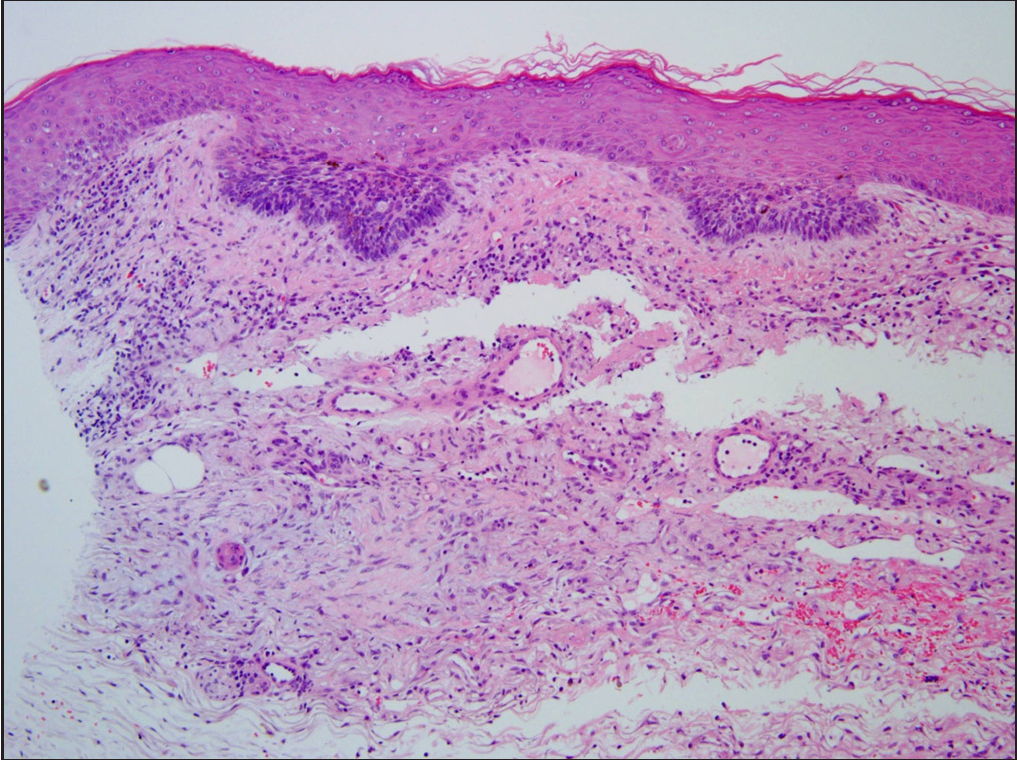

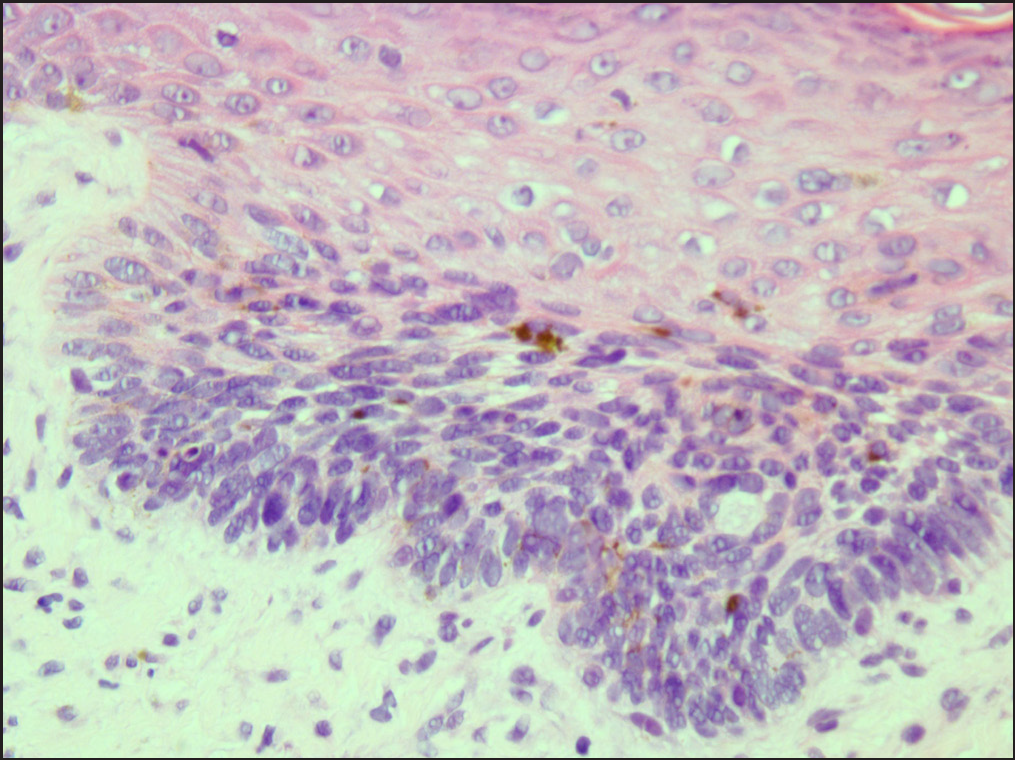

A 104-year-old woman presented with several pruritic and painful violaceous patches and plaques of various sizes on her right back, which had persisted for 2 years [Figure 1]. She had developed herpes zoster in the same anatomical location 20 years earlier. She had a medical history of cholangiocarcinoma and hypertension. A skin biopsy was performed to diagnose and rule out cutaneous metastasis of malignancy. Histopathological examination revealed nests of basaloid cells arising from the basal layer. The nests did not extend beyond the papillary dermis [Figures 2]. Based on the histopathological findings, we diagnosed the patient as having WIR with superficial BCC at the site of a previous herpes zoster infection. Considering the patients’ advanced age and lesion size, surgical treatment was deemed inappropriate. Instead, imiquimod 5% cream was prescribed, and the patient’s instructions were to apply the cream to the affected area three times a week.

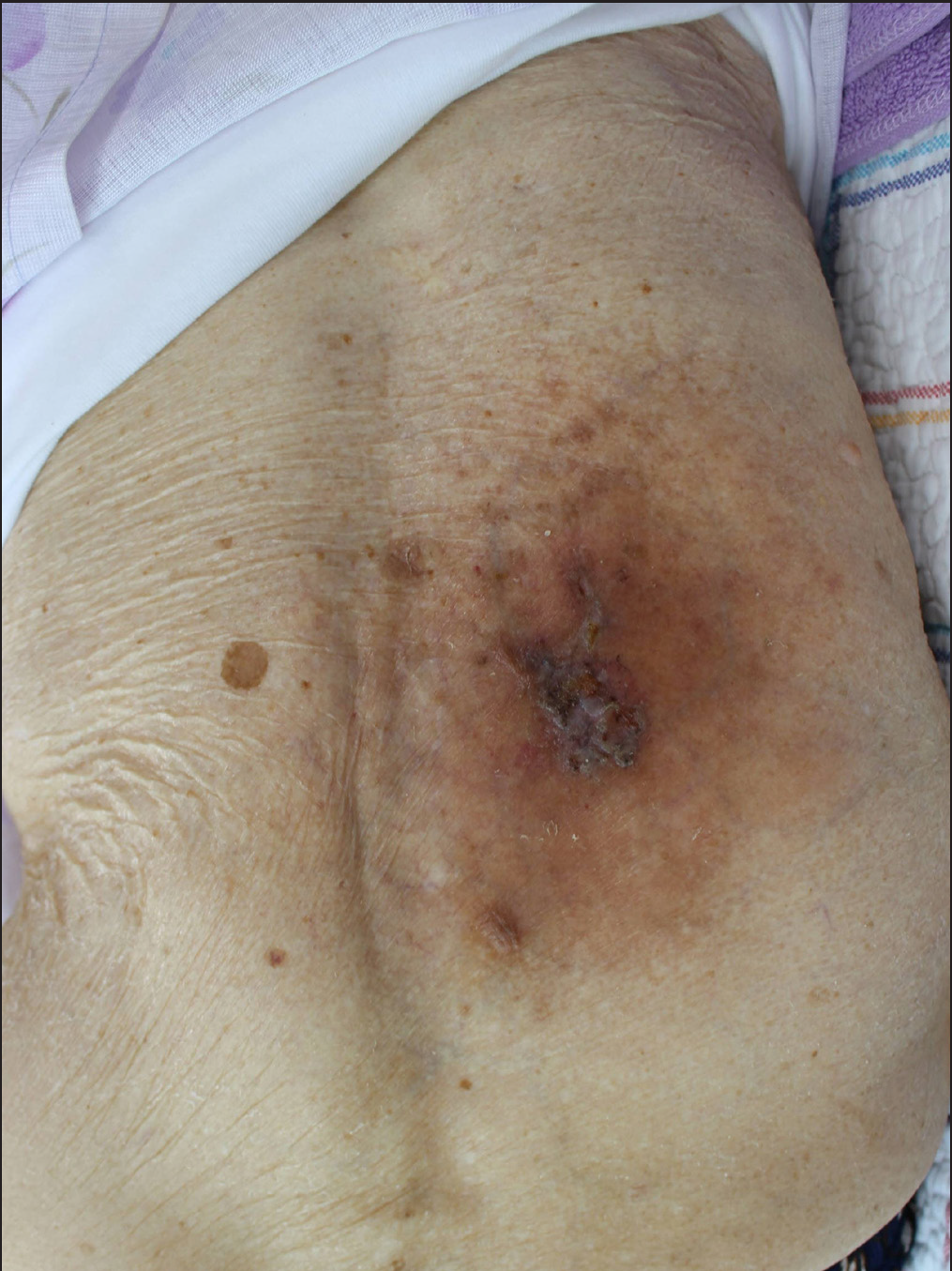

The size and thickness of the lesions gradually reduced after 7 months of treatment with imiquimod [Figure 3]. The patient is presently undergoing follow-up care.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Previously, Ruocco et al. reviewed 189 well-documented cases of WIR, of which 37 patients had malignant tumors, including breast carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, BCC, basosquamous carcinoma, Bowen’s disease, metastasis, and angiosarcoma.2 It is interesting to note that in WIR, the interval between primary and secondary diseases can vary widely, ranging from a few days to several years. Although numerous dermatoses have been reported to manifest as WIR, only five cases of BCC have been reported, with intervals ranging from 1 year to 35 years (mean 12.1 ± 11.5 years).2,3 In our case, the interval was 18 years. This highlights the importance of continuous follow-up and monitoring for the development of new dermatoses at sites of previous herpes zoster infections or skin injuries.

Although the mechanism and pathogenesis of WIR are still unclear, there are various hypotheses regarding the same, some of which are as follows: (1) viral particles remaining in the tissue may cause the second disease; (2) immunologic changes following viral infection may make the skin more vulnerable, leading to the second disease; (3) microvascular alteration acts as a cofactor in WIR; (4) neurologic alteration may interact with the immune system.1 Among these hypotheses, we speculate that the “locus minoris resistentiae” or immunocompromised cutaneous district may have been the mechanism in our case. This concept suggests that there may be areas of the body that are more susceptible to immune dysfunction. Varicella zoster virus can cause neural damage and result in the altered secretion of neuromediators, which interact with membrane receptors of immune cells. This can lead to local immune dysfunction and encourage the development of another disease in the affected dermatome.4 The fact that an increased prevalence of BCC is observed in people with a history of herpes zoster infection supports this hypothesis.5

The pathogenesis and interval of BCC after herpes zoster infection, possibly due to WIR, are not yet fully understood. In our case, it may have been a superficial BCC that was idiopathic because of advanced age; however, attention was paid to the association because it occurred at the site of a previous herpes zoster infection. Dermatologists should be aware that various dermatoses, including BCC, may occur at the site of healed herpes zoster. Further studies are needed to better understand the relationship between BCC and a history of herpes zoster and thereby determine the underlying mechanisms.

留言 (0)