Life-long maintenance of skeletal muscle integrity is maintained by a population of tissue resident adult muscle stem cells (MuSCs), or “satellite cells”, embedded between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and individual myofibers (Mauro, 1961). The indispensable role of MuSCs, distinguished by their tissue-specific expression of the transcription factor Pax7, has been repeatedly demonstrated (Lepper et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2011; Relaix and Zammit, 2012; Von Maltzahn et al., 2013). Despite protocols that afford efficient isolation of primary MuSCs from both human and murine tissues, therapeutic application of these cells is severely limited by donor availability and an inability to expand these cells in vitro (Montarras et al., 2005; Yi and Rossi, 2011; Liu et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2021). Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) have emerged as a promising, scalable, source of myogenic progenitors (MPs). Studies into the developmental origins of MuSCs have led to a deep understanding of the biological processes underlying the emergence of these cells within skeletal muscle tissue (Chal and Pourquié, 2017). These efforts, along with those affording the generation of PSCs via reprogramming of adult somatic tissue (iPSCs), have been foundational to the concept of using autologous MPs therapeutically (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Barberi et al., 2007).

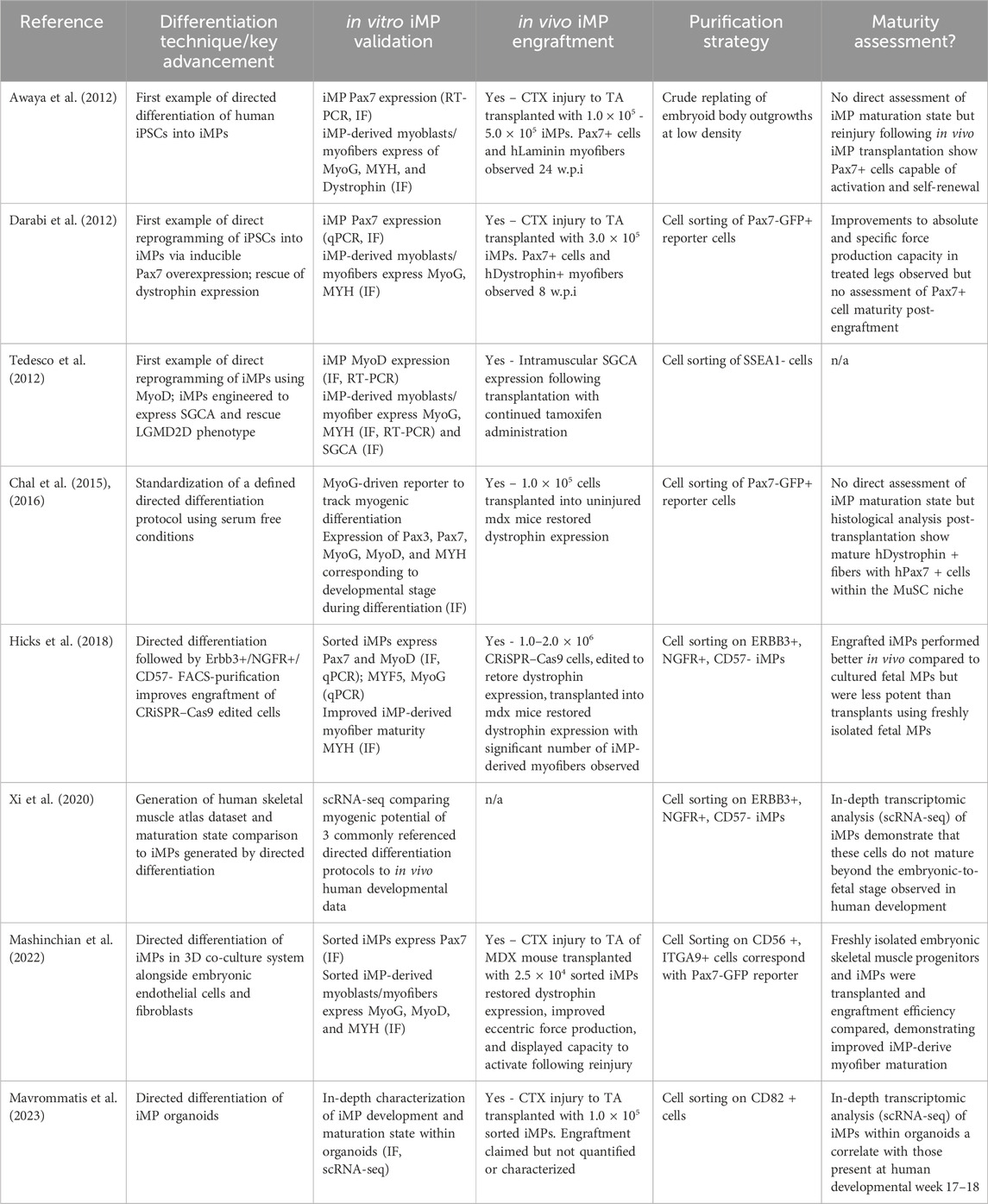

In this perspective, we present the state-of-the-art in generating and purifying therapeutically relevant iPSC-derived MPs (iMPs), focusing on workflows that enhance their similarity to MuSCs and improve engraftment for de novo muscle formation and MuSC niche repopulation (Table 1). We then explore an emerging area of cellular engineering which, despite rapid adoption in fields like immunology, remains relatively undeveloped in skeletal muscle therapeutics. Synthetic biology and the engineering of cells to perform functions beyond their natural roles presents a transformative opportunity to reshape the current paradigm of iMP-based therapies.

Table 1. Key findings published that have progressed the field of iMP generation to its current state. The stability and flexibility afforded by directed differentiation are highlighted along with the maturation characteristics that we believe to be critical to improving iMP therapeutic application.

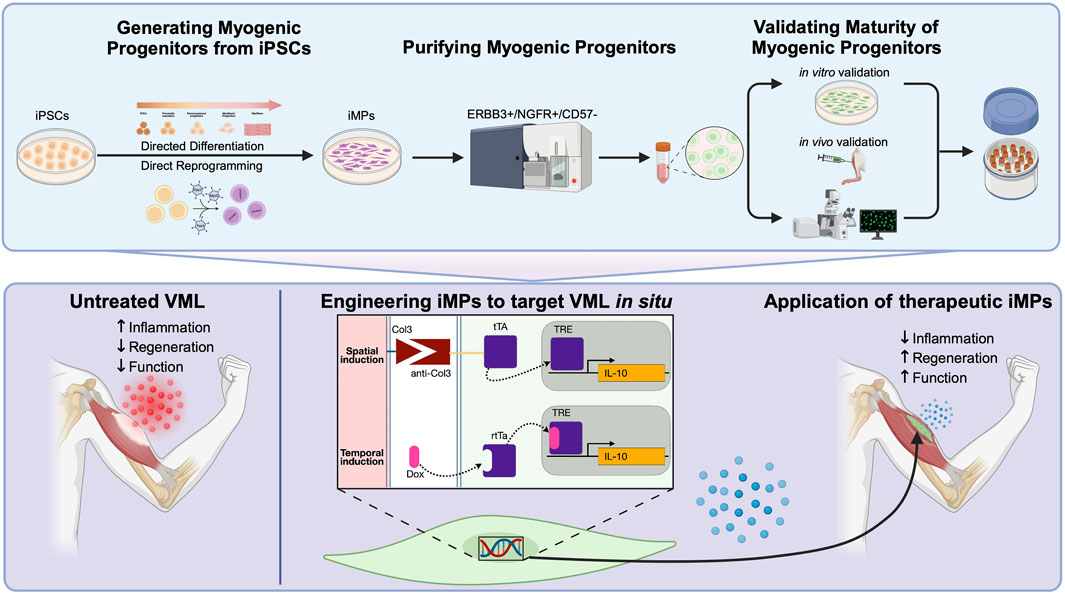

2 Making muscle: differentiation and purification of iMPsToday, a number of well-established protocols for the production of iMPs exist, each falling into one of two categories (Iberite et al., 2022). Direct reprogramming relies on the overexpression of myogenic transgenes to force myogenic potential, while directed differentiation generates iMPs through meticulous recapitulation of the conditions that lead to developmental emergence of MuSCs in vivo (Hicks et al., 2018; Xi et al., 2020; Nalbandian et al., 2021). While these two methods for generating iMPs differ, both aim to produce cells that can be used directly or, preferably, cryopreserved in viable cell banks for downstream application (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (Top panel) Standardized workflow for the generation and validation of iPSC-derived myogenic progenitors (iMPs) utilizing either directed differentiation or direct reprogramming approaches. Following differentiation, FACS isolation using ERBB3+/NGFR+/CD57− result in iMPs that are more mature, potent, and phenotypically comparable to MuSCs. Verification of myogenicity immediately after cell sorting include immunofluorescent staining for markers like Pax7 and MyoG and MYH and Dystrophin after secondary differentiation into myotubes. In parallel, cells should be further validated for their capacity to engraft and form de novo myofibers in vivo. Further histological assessment should confirm the capacity for some iMPs to retain Pax7 expression and populate the MuSC niche. (Bottom panel) An example of iMPs engineering to target volumetric muscle loss (VML) pathophysiology. Untreated VML is underscored by dysregulated fibrosis in the damaged muscle leading to poor regenerative potential. Engineering iMPs that express IL-10, a cytokine demonstrated to have potent pro-regenerative effects in VML, could be further enhanced by the spatio-temporal delivery afforded by this system. The improved regenerative environment should act synergistically to alleviate fibrosis and improve myogenic potential in the transplanted cells.

2.1 Direct reprogrammingOverexpression of the myogenic transcription factors MyoD and Pax7 both reliably induce iPSCs toward a myogenic fate. The first examples of iMP direct reprogramming demonstrated that activation of these inducible transgenes generated cells that reliably engraft into muscle tissue, and are capable of restoring tissue specific expression of dystrophin and a-sarcoglycan in their respective murine disease models (Darabi et al., 2012; Tedesco et al., 2012). Since these initial demonstrations, direct reprogramming protocols have been used to reliably produce iMPs with similar regenerative capacity (Tanaka et al., 2013; Quattrocelli et al., 2015; Uezumi et al., 2016; Azzag et al., 2022). Despite these successes, a number of caveats specific to direct reprogramming warrant consideration. First, many direct reprogramming strategies adopt the use of small molecules and growth factors to prime iPSCs towards a mesodermal lineage prior to myogenic transgene induction, raising the question of whether introducing transgenes for the final step of myogenic specification is truly necessary (Magli et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019). Correspondingly, direct reprogramming inherently skips critical developmental maturation steps and little has been done to assess the relative developmental maturity of iMPs generated using this method. We will elaborate on the importance of iMP maturity in later sections; however, the lack of evidence for maturation in these cells represents one of the most critical shortcomings of direct reprogramming. Concerns over the risks associated with random transgene integration in direct reprogramming have also drawn scrutiny. Targeting transgenes to genetic safe-harbor loci and transient overexpression systems have been developed to reduce the perceived risks associated with transgene integration but are likely precautionary and immaterial to therapeutic application (Sadelain et al., 2012; Ordovás et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2021; Shin et al., 2020).

Despite the drawbacks associated with direct reprogramming the FDA has recently given clinical trial approval for a first-of-its-kind muscular dystrophy treatment in which allogeneic cell banks, induced to a myogenic lineage using Pax7 overexpression, will be assessed for safety, tolerability, and engraftment capacity in DMD patients (Myogenica, 2024). Successes in these early trials have the potential to transform the landscape of myopathy-targeting therapeutics and open the door to more advanced therapeutic modalities, as we discuss below.

2.2 Directed differentiationUnlike direct reprogramming, directed differentiations use transgene-free methods of generating iMPs, relying on a holistic consideration of the developmental conditions that give rise to adult MuSCs. The first directed differentiation protocols were adapted from human embryonic stem cell (hESC) systems, and relied on undefined medias to differentiate embryoid body outgrowths into iMPs (Barberi et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2009; Mizuno et al., 2010; Awaya et al., 2012). While heterogeneity in the resulting populations was duly noted, these early studies provided evidence of myogenic potential in human iPSCs, paving way for more sophisticated protocols.

In 2016, two seminal papers established the culture conditions for generating Pax7+ myogenic progenitors from human iPSCs, optimizing an approach that induces presomitic mesoderm (PSM) specification prior to myogenic progenitor differentiation (Chal et al., 2015; Chal et al., 2016; Shelton et al., 2016). The resulting iMPs demonstrated robust myogenic capacity, but the rationale for the timing and concentration of certain growth factors remains dubious, even today. As these remain two of the most cited protocols for the generation of iMPs, a more granular screening aimed at optimizing these conditions is warranted and overdue. Data on the transition from early fetal to adult skeletal muscle in human tissue isolates are publicly available and may provide insights that would resolve this ambiguity (Xi et al., 2020).

Today, generation of iMPs using PSM to myogenic precursor differentiation has become the gold-standard in directed differentiations. However, the resulting cells are heterogeneous and there remains potential for further optimization and refinement (Bou Akar et al., 2024). Directed differentiations can generate iMPs that stably express Pax7 and are a more developmentally accurate recapitulation of MuSC-like cells than those generated via direct reprogramming. Standardization of directed differentiation protocols will be crucial to delivering therapeutic-grade iMPs. Towards this end STEMCELL technologies has released a product (STEMdiff™ Myogenic Progenitor Supplement Kit), that reliably produces a robust population of iMPs. cGMP qualification of products like this would represent a major step towards therapeutic application.

2.3 Purification strategies to isolate iMPsRegardless of the method used to generate iMPs, their therapeutic potential remains constrained by population heterogeneity. Direct reprogramming protocols utilize Pax7-driven fluorescent reporters to facilitate iMP purification, but neural crest progenitors, which also express Pax7, commonly contaminate these cultures (Basch et al., 2006). Non-transgenic directed differentiation strategies lack fluorescent reporters, necessitating the identification of surface markers that correlate with myogenic Pax7 expression. Cell surface markers for the purification of adult MuSCs have been identified, but are not reliably expressed in human iMPs (Wosczyna and Rando, 2018; Mierzejewski et al., 2020). Characterization of Pax7+ iMPs has led to the identification of several combinations of cell surface markers that aid in their purification. While CD54, CD10, CD82, CD56, and CDH13, and FGFR-4 all correlate with Pax7+ expression in human iMPs, the epidermal growth factor receptor ERBB3 has thus far been demonstrated the most reliable (Choi et al., 2016; Uezumi et al., 2016; Hicks et al., 2018; Sakai-Takemura et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Nalbandian et al., 2021). In combination with positive selection for CD271 and negative selection of CD57 neuroectodermal contaminates, ERBB3 allows robust purification of iMPs that are phenotypically similar to the MuSCs observed developmentally during secondary myogenesis (Hicks et al., 2018; Tey et al., 2019). To validate myogenicity after cell sorting, iMPs should be plated and immediately stained for Pax7 and MyoG. Additional confirmation of myogenic potential should be confirmed by staining for myosin heavy chain (MYH) and dystrophin following subsequent differentiation into myotubes.

3 Maturation of iPSC derived myogenic progenitors beyond the fetal phenotypeDespite improvements in the generation and purification of iMPs over the last decade, these cells invariably retain a late-embryonic/early-fetal phenotype, which like fetal MuSCs, show reduced engraftment capacity compared to adult MuSCs (Castiglioni et al., 2014; Xi et al., 2020). Strategies to address this lack of maturity include culturing iMPs in a 3D macroenvironment, external stimulation, and in vivo maturation (Khodabukus et al., 2019; Selvaraj et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2022; van der Wal et al., 2023; Crist et al., 2024). As maturation state remains the most significant identifiable cause of poor iMP engraftment, a collective effort must be made to address this problem.

3.1 3-dimensional and co-culture systems3D directed differentiation of iMPs attempts to integrate the culture conditions established in 2D protocols with the spatial/environmental cues afforded by 3D organization. In one study, fully humanized multilineage embryoids containing iPSCs, growth-arrested embryonic fibroblasts and embryonic endothelial cells were grown together using a directed differentiation protocol, resulting in robust myogenic induction of the iPSCs; after only 13 days 40%–50% of cells in these embryoids were Pax7+ (Mashinchian et al., 2022). Unfortunately, the method used in this study to quantify Pax7 via RNA-FISH misrepresents the true myogenic Pax7 population, and staining with surface markers for Pax7-associated proteins significantly reduced the number of truly myogenic cells. In addition, despite acceptable engraftment and improvements to functional force production, these cells exhibited an embryonic (week 9) phenotype, indicating that they are no more mature than those produced in 2D systems.

In a more recent publication, human skeletal muscle organoids formed a largely myogenic population of cells (∼90%). Interestingly, a significant number of mesenchymal (∼4%) and neural (∼5%) cells also populated these 3D structures. While not explicitly studied, the heterogenous 3D structure was likely partially responsible for the maturation of the resulting Pax7+ iMPs, which closely resembled a fetal week 17 phenotype (Mavrommatis et al., 2023). Cell-cell communication analysis of the scRNA sequencing data generated in this work identified a number of upregulated ECM components (COL1A2, COL5A2, COL5A3, FN1) and transcription factors (FBN1, CHODL, SPRY1) that could be targeted in 2D or 3D systems to further mature iMPs.

While inducing differentiation of iMPs using 3D culture systems is relatively new, the application of differentiated iMPs within 3D systems has been widely reported (Rao et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019; van der Wal et al., 2023). It is established that 3D co-cultures can mimic the MuSC niche, enhance myofiber maturation, boost in vivo engraftment potential, and act as effective disease models (Quarta et al., 2016; Quarta et al., 20017; Bersini et al., 2018; Maffioletti et al., 2018; Rao et al., 2018; Bakooshli et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Urciuolo et al., 2020; Massih et al., 2023). While recovery of mature iMPs from 3D systems may limit certain therapeutic applications (e.g., those requiring single cell suspensions), it may enhance their utility in others (e.g., traumatic skeletal muscle injury). 3D systems should be considered valuable tools for assessing iMP maturation and could help to further identify culture conditions that enhance this process.

3.2 Stimulation of iMPs to improve maturityStimulation of myogenic cells can be achieved through either mechanical, chemical, electrical, or static tension. Early studies of C2C12-derived myofibers seeded within 3D collagen scaffolds demonstrated that electrical stimulation of these cells improved sarcomere organization and myofiber maturity (Park et al., 2008). In 2018, Rao et al. demonstrated that myofibers grown within their 3D scaffolds supported a population of self-sustaining Pax7+ iMPs (Rao et al., 2018). Despite thorough characterization of this stimulatory effect on myofiber maturity and force production, the Pax7+ iMP population was not further characterized. In a more recent study, van der Wal et al. directly compared directly differentiated iMP-derived myofibers to those of primary human myoblasts, showing that electrical stimulation of the 3D scaffolds produced comparable force production measurements (van der Wal et al., 2023). While this study provided a detailed physical and proteomic analysis of the resulting myofibers, the presence and maturity of Pax7+ cells within the constructs were not reported. In vivo, maturation of the MuSC compartment coincides with myofiber maturation following secondary myogenesis. Future studies should make use of systems like those described above to assess the effects of stimulation on the capacity of iMP-derived myofibers to support maturation of the associated iMPs.

3.3 The body is the best bioreactorHuman MuSC development is a spatiotemporally coordinated process guided by concurrent maturation of the surrounding tissue (Chal and Pourquié, 2017). Differentiation of iPSCs to fully mature iMPs may therefore be limited by constraints inherent to culture systems. Comparing MuSCs with iMPs matured in vivo or in vitro has demonstrated that in vivo-matured iMPs more closely resembled adult MuSCs, whereas in vitro-matured iMPs retained a more fetal-like transcriptomic profile (Incitti et al., 2019). Important myogenic regulators (Stat3, Jun, Itga7, Tgfb2, Notch1, Notch3, and Jag1) and genes involved in ECM regulation were upregulated in the in vivo matured iMPs compared to those matured in vitro. Future studies aimed at targeted activation or inhibition of signaling pathways in which these factors are involved may improve maturation of iMPs in vitro. Likewise, incorporating the identified ECM modalities within engineered scaffolds may expedite the maturation of these cells when applied within certain therapeutic contexts. The key takeaway from these data is that iMP maturity in vitro may be less significant to successful therapeutic application than previously thought; instead, we may be able to rely on in vivo maturation to carry these cells towards a more MuSC-like phenotype.

4 Engineering iMPs to improve therapeutic potentialAdvancements in the generation, purification, and maturation of iMPs justify consideration of how to proceed with their therapeutic application. Recent reviews have highlighted the need for pre-clinical testing of the safety and efficacy of iMPs but emphasis is often placed on those capable of addressing muscular dystrophies (Iberite et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2024). In this section we will instead discuss tissue engineering strategies focused on the treatment of volumetric muscle loss (VML). We will then consider how we might employ iMPs as a therapeutic platform, focusing potential application of these cells as treatments for systemic diseases.

4.1 Current therapeutic applications of iMPs in VMLVML is characterized by a loss of tissue architecture that leads to chronic fibrosis and an associated loss of function (Corona et al., 2015). Current clinical treatments rely on crude muscle flap surgeries, which are limited by donor-site availability (Greising et al., 2017). Experimental therapeutics targeting VML aim to restore tissue integrity and function through the use of 3D scaffolds seeded with myoblasts or MuSCs (Corona et al., 2013; Quarta et al., 2017; Goldman et al., 2018). Despite the obvious application of iMPs as a substitute for patient-derived MuSCs, few studies have reported successful therapeutic application of these cells (Wu et al., 2021; Pinton et al., 2023). iMP maturity likely dictates survival within the scaffold and the capacity to successfully generate functional de novo muscle.

4.2 Augmenting scaffold design to improve iMP efficacyScaffold design is critical to targeting VML pathophysiology (Wolf et al., 2015). In previous sections we have alluded to different ECM components that might help to mature iMPs in vitro. Current scaffolds can include either synthetic or natural material compositions, with natural hydrogels generally favored due to their intrinsic biocompatibility (Fischer et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2022). Hydrogels are frequently generated using proteins like collagen or fibrinogen, or polysaccharides such as hyaluronic acid or alginate. Those composed of proteins - specifically collagen - rarely consider particular isoforms, which have diverse functional characteristics (Goldman et al., 2018; Matthias et al., 2018; Pollot et al., 2018). Future studies should aim to incorporate specific collagen isotypes, like those already identified as important for iMP maturation, into scaffolds seeded with iMPs to improve maturation and survivability (Incitti et al., 2019). Additional considerations, such as the addition of growth factors and materials that promote revascularization and reinnervation must also be considered but are outside the scope of this perspective (Wu et al., 2021).

4.3 iMPs as in vivo biologics factoriesSkeletal muscle is a highly vascularized, metabolically active tissue, making it an excellent vehicle for the delivery of biological therapeutics. The engraftment of iMPs, while imperfect, is likely sufficient to deliver effective cell-based synthetic gene products in situ. A key advantage of iMPs is their capacity to be extensively engineered prior to differentiation and/or transplantation, affording flexibility in tailoring treatments. Utilizing iMPs as a delivery platform for therapeutics like growth factors, cytokines, and biologics represents a highly promising, yet largely untapped, application. This approach could revolutionize the delivery of therapeutics by directly targeting affected tissues, enhancing treatment precision and efficacy.

Following VML, a dysregulated immune response results in persistent inflammation, elevated TGFβ expression within the damaged tissue, and resulting in fibrosis (Larouche et al., 2021). Experimental treatments have successfully alleviated fibrosis through systemic administration of anti-fibrotic agents that target TGFβ, but these treatments have dangerous off-target effects (Garg et al., 2014; Greising et al., 2019; Larouche et al., 2022). More recently, work has demonstrated that local administration of the pro-regenerative cytokine IL-10 can improve the regeneration in skeletal muscle following VML (Huynh et al., 2023). Engineering iMPs to target inflammation and fibrosis - either by locally secreting anti-TGFβ antibodies or by counteracting inflammation using pro-regenerative cytokines such as IL-10 - could enhance regeneration after VML while mitigating the risks of systemic anti-TGFβ therapies (Borok et al., 2020; Narasimhulu and Singla, 2023). The capacity to generate inducible transgenes, controlled either temporally or spatially, would further improve the precision of these treatments (Figure 1).

In another example, we imagine a system in which iMPs engineered to constitutively express and secrete hormones responsible for blood glucose-homeostasis, might alleviate hyperglycemia in diabetic patients (Xie and Fussenegger, 2018). Synthetic circuits enabling glucose-mediated insulin secretion have been developed, bypassing the need for islet cells, which remain targeted by the immune system in type 1 diabetics receiving islet transplants (Xie et al., 2016). Type 2 diabetes might also be targeted using iMP-delivered synthetic gene circuits that secrete adiponectin to improve insulin sensitivity (Ye et al., 2017). Hypothetically, these synthetic gene circuits, applied to iMPs transplanted in otherwise healthy diabetic patients, could counteract hyperglycemia without the documented shortcomings of iPSC-based pancreatic beta cell therapies (Maxwell and Millman, 2021).

Thoughtful design of inducible synthetic transgenes should allow for iMPs to deliver therapeutics either locally or systemically. While the immediate application of these systems to target VML pathology are evident, the application of iMPs as a therapeutic delivery platform targeting systemic disease has yet to be discussed in the literature. The capacity for iMPs to persist long term as engrafted myofibers makes them an attractive alternative to other cell-based therapies that are often limited by poor engraftment efficiency and survivability (Levy et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). We propose that future studies aiming to address disease using cell therapeutics consider the use of iMPs as a reliable delivery platform.

4.4 iMPs as biosensors to study cellular dynamicsTemporal regulation of synthetic gene circuits is easily achieved through the use of inducible promoters, but the spatial organization of regenerating skeletal muscle may provide additional, therapeutically relevant, cues. Spatial transgene regulation has been achieved through the engineering of synthetic receptors capable of recognizing specific ligands, resulting in customizable sense/response behaviors (Roybal et al., 2016; Scheller et al., 2018). Synthetic notch (synNotch) receptors have proven a particularly powerful tool, capable of inducing the expression of myogenic transgenes in a spatially-regulated context (Morsut et al., 2016). Application of the synNotch system in vivo has demonstrated broad utility, from serving as an intercellular contact sensor capable of fate-mapping endothelial cells during development to enhancing CAR cell therapeutic efficacy (Hyrenius-Wittsten et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). iMPs engineered to express customized synNotch constructs could provide spatial, context-dependent, regulation of transgene activation/deactivation. For example, pro-fibrotic collagens 3, 4 and 6 are significantly upregulated in the fibrotic lesion following VML (Hoffman et al., 2022). A self-regulating, cell-based synNotch system that uses antiCol3-tTa to control expression of anti-TGFβ antibody expression could enable targeted delivery, limiting expression to areas only where pro-fibrotic collagens are present (Figure 1).

4.5 Engineering iMPs to exogenously stimulate myofibersWhen skeletal muscle is insufficiently innervated exogenous electrical stimulation can improve both the maturation and force production of the myofibers, aiding in the rehabilitation of muscle strength (Gordon and Mao, 1994; Crist et al., 2024). Optogenetic switches, which allow for transdermal stimulation of skeletal muscle using visible light, represents an attractive alternative to invasive patch clamps. Optogenetic switches have already proven capable of driving skeletal muscle contraction both in vitro and in vivo (Bruegmann et al., 2015; Ganji et al., 2021). Their therapeutic application as part of an iMP-based treatment should be investigated as it may allow for partial restoration of muscle function in spinal cord injury patients; or, at the very least, assist in the rehabilitation process.

5 Discussion/conclusionThe finding that myogenic differentiation is enhanced by prior PSM specification, whether it be in directed differentiation or direct reprograming protocols, has been fundamental to the generation of therapeutically relevant iMPs. Likewise, the ability to accurately purify the ERBB3+/NGFR+/CD57- myogenic Pax7+ population using cell sorting has considerably improved the purity of the resulting iMPs. Although imperfect, the current maturation capacity of these protocols allows for efficient engraftment of these cells and the generation of iMP-derived myofibers in vivo. While improvements within each of these categories are sure to further enhance the capacity for these cells to behave like adult MuSCs, using current iMPs as a therapeutic delivery platform opens the door to a wonderfully diverse and novel way of treating myopathies and systemic diseases alike. We encourage those working on cell-based therapies to consider new ways in which these cells can be employed and toward a future in which long-term iMP-based therapeutics can become a platform for therapeutics delivery.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributionsMH: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. FR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. MH is supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FBD-181513) F.M.V.R. is supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-159908).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ReferencesAwaya, T., Kato, T., Mizuno, Y., Chang, H., Niwa, A., Umeda, K., et al. (2012). Selective development of myogenic mesenchymal cells from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One 7, e51638–e51639. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051638

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Azzag, K., Bosnakovski, D., Tungtur, S., Salama, P., Kyba, M., and Perlingeiro, R. C. R. (2022). Transplantation of PSC-derived myogenic progenitors counteracts disease phenotypes in FSHD mice. NPJ Regen. Med. 7, 43–11. doi:10.1038/s41536-022-00249-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bakooshli, M. A., Lippmann, E. S., Mulcahy, B., Iyer, N., Nguyen, C. T., Tung, K., et al. (2019). A 3d culture model of innervated human skeletal muscle enables studies of the adult neuromuscular junction. Elife 8, 1–29. doi:10.7554/eLife.44530

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barberi, T., Bradbury, M., Dincer, Z., Panagiotakos, G., Socci, N. D., and Studer, L. (2007). Derivation of engraftable skeletal myoblasts from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Med. 13, 642–648. doi:10.1038/nm1533

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Basch, M. L., Bronner-Fraser, M., and García-Castro, M. I. (2006). Specification of the neural crest occurs during gastrulation and requires Pax7. Nature 441, 218–222. doi:10.1038/nature04684

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bersini, S., Gilardi, M., Ugolini, G. S., Sansoni, V., Talò, G., Perego, S., et al. (2018). Engineering an environment for the study of fibrosis: a 3D human muscle model with endothelium specificity and endomysium. Cell. Rep. 25, 3858–3868. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.092

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bou Akar, R., Lama, C., Aubin, D., Maruotti, J., Onteniente, B., Esteves de Lima, J., et al. (2024). Generation of highly pure pluripotent stem cell-derived myogenic progenitor cells and myotubes. Stem Cell. Rep. 19, 84–99. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.11.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bruegmann, T., Van Bremen, T., Vogt, C. C., Send, T., Fleischmann, B. K., and Sasse, P. (2015). Optogenetic control of contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nat. Commun. 6, 7153–7158. doi:10.1038/ncomms8153

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Castiglioni, A., Hettmer, S., Lynes, M. D., Rao, T. N., Tchessalova, D., Sinha, I., et al. (2014). Isolation of progenitors that exhibit myogenic/osteogenic bipotency in vitro by fluorescence-activated cell sorting from human fetal muscle. Stem Cell. Rep. 2, 92–106. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.12.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chal, J., Al Tanoury, Z., Hestin, M., Gobert, B., Aivio, S., Hick, A., et al. (2016). Generation of human muscle fibers and satellite-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1833–1850. doi:10.1038/nprot.2016.110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chal, J., Oginuma, M., Al Tanoury, Z., Gobert, B., Sumara, O., Hick, A., et al. (2015). Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to muscle fiber to model Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 962–969. doi:10.1038/nbt.3297

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chang, H., Yoshimoto, M., Umeda, K., Iwasa, T., Mizuno, Y., Fukada, S., et al. (2009). Generation of transplantable, functional satellite-like cells from mouse embryonic stem cells. FASEB J. 23, 1907–1919. doi:10.1096/fj.08-123661

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Choi, I. Y., Lim, H. T., Estrellas, K., Mula, J., Cohen, T. V., Zhang, Y., et al. (2016). Concordant but varied phenotypes among duchenne muscular dystrophy patient-specific myoblasts derived using a human iPSC-based model. Cell. Rep. 15, 2301–2312. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corona, B. T., Rivera, J. C., Owens, J. G., Wenke, J. C., and Rathbone, C. R. (2015). Volumetric muscle loss leads to permanent disability following extremity trauma. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 52, 785–792. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.07.0165

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corona, B. T., Wu, X., Ward, C. L., McDaniel, J. S., Rathbone, C. R., and Walters, T. J. (2013). The promotion of a functional fibrosis in skeletal muscle with volumetric muscle loss injury following the transplantation of muscle-ECM. Biomaterials 34, 3324–3335. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.061

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Crist, S. B., Azzag, K., Kiley, J., Coleman, I., Magli, A., and Perlingeiro, R. C. R. (2024). The adult environment promotes the transcriptional maturation of human iPSC-derived muscle grafts. NPJ Regen. Med. 9, 16–11. doi:10.1038/s41536-024-00360-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Darabi, R., Arpke, R. W., Irion, S., Dimos, J. T., Grskovic, M., Kyba, M., et al. (2012). Human ES- and iPS-derived myogenic progenitors restore DYSTROPHIN and improve contractility upon transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell. Stem Cell. 10, 610–619. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fischer, K. M., Scott, T. E., Browe, D. P., McGaughey, T. A., Wood, C., Wolyniak, M. J., et al. (2020). Hydrogels for skeletal muscle regeneration. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 7, 353–361. doi:10.1007/s40883-019-00146-x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ganji, E., Chan, C. S., Ward, C. W., and Killian, M. L. (2021). Optogenetic activation of muscle contraction in vivo. Connect. Tissue Res. 62, 15–23. doi:10.1080/03008207.2020.1798943

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Garg, K., Corona, B. T., and Walters, T. J. (2014). Losartan administration reduces fibrosis but hinders functional recovery after volumetric muscle loss injury. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 1120–1131. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00689.2014

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goldman, S. M., Henderson, B. E. P., Walters, T. J., and Corona, B. T. (2018). Co-delivery of a laminin-111 supplemented hyaluronic acid based hydrogel with minced muscle graft in the treatment of volumetric muscle loss injury. PLoS One 13, 01912455–e191315. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191245

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Greising, S. M., Corona, B. T., McGann, C., Frankum, J. K., and Warren, G. L. (2019). Therapeutic approaches for volumetric muscle loss injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 25, 510–525. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2019.0207

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Greising, S. M., Rivera, J. C., Goldman, S. M., Watts, A., Aguilar, C. A., and Corona, B. T. (2017). Unwavering pathobiology of volumetric muscle loss injury. Sci. Rep. 7, 13179–13214. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13306-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hicks, M. R., Hiserodt, J., Paras, K., Fujiwara, W., Eskin, A., Jan, M., et al. (2018). ERBB3 and NGFR mark a distinct skeletal muscle progenitor cell in human development and hPSCs. Nat. Cell. Biol. 20, 46–57. doi:10.1038/s41556-017-0010-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hoffman, D. B., Raymond-Pope, C. J., Sorensen, J. R., Corona, B. T., and Greising, S. M. (2022). Temporal changes in the muscle extracellular matrix due to volumetric muscle loss injury. Connect. Tissue Res. 63, 124–137. doi:10.1080/03008207.2021.1886285

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huynh, T., Reed, C., Blackwell, Z., Phelps, P., Herrera, L. C. P., Almodovar, J., et al. (2023). Local IL-10 delivery modulates the immune response and enhances repair of volumetric muscle loss muscle injury. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–15. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-27981-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hyrenius-Wittsten, A., Su, Y., Park, M., Garcia, J. M., Alavi, J., Perry, N., et al. (2021). SynNotch CAR circuits enhance solid tumor recognition and promote persistent antitumor activity in mouse models. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabd8836. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abd8836

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Iberite, F., Gruppioni, E., and Ricotti, L. (2022). Skeletal muscle differentiation of human iPSCs meets bioengineering strategies: perspectives and challenges. NPJ Regen. Med. 7, 23–30. doi:10.1038/s41536-022-00216-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Incitti, T., Magli, A., Darabi, R., Yuan, C., Lin, K., Arpke, R. W., et al. (2019). Pluripotent stem cell-derived myogenic progenitors remodel their molecular signature upon in vivo engraftment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 4346–4351. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808303116

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jensen, J. B., Møller, A. B., Just, J., Mose, M., de Paoli, F. V., Billeskov, T. B., et al. (2021). Isolation and characterization of muscle stem cells, fibro-adipogenic progenitors, and macrophages from human skeletal muscle biopsies. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 321, C257–C268. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00127.2021

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Khodabukus, A., Madden, L., Prabhu, N. K., Koves, T. R., Jackman, C. P., Muoio, D. M., et al. (2019). Electrical stimulation increases hypertrophy and metabolic flux in tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle. Biomaterials 198, 259–269. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.058

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, H., Selvaraj, S., Kiley, J., Azzag, K., Garay, B. I., and Perlingeiro, R. C. R. (2021). Genomic safe harbor expression of PAX7 for the generation of engraftable myogenic progenitors. Stem Cell. Rep. 16, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.11.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, J., Oliveira, V. K. P., Yamamoto, A., and Perlingeiro, R. C. R. (2017). Generation of skeletal myogenic progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells using non-viral delivery of minicircle DNA. Stem Cell. Res. 23, 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2017.07.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, J. H., Kim, I., Seol, Y. J., Ko, I. K., Yoo, J. J., Atala, A., et al. (2020). Neural cell integration into 3D bioprinted skeletal muscle constructs accelerates restoration of muscle function. Nat. Commun. 11, 1025–1112. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14930-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Larouche, J. A., Kurpiers, S. J., Yang, B. A., Davis, C., Fraczek, P. M., Hall, M., et al. (2021). Neutrophil and natural killer cell imbalances prevent muscle stem cell mediated regeneration following murine volumetric muscle loss. bioRxiv 1, 2021. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111445119

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Larouche, J. A., Wallace, E. C., Spence, B. D., Johnson, S. A., Kulkarni, M., Buras, E., et al. (2022). Spatiotemporal mapping of immune and stem cell dysregulation after volumetric muscle loss 2. doi:10.1101/2022.06.03.494707

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lepper, C., Partridge, T. A., and Fan, C. M. (2011). An absolute requirement for pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 138, 3639–3646. doi:10.1242/dev.067595

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Levy, O., Kuai, R., Siren, E. M. J., Bhere, D., Milton, Y., Nissar, N., et al. (2020). Shattering barriers toward clinically meaningful MSC therapies. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–18. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba6884

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, L., Cheung, T. H., Charville, G. W., and Rando, T. A. (2015). Isolation of skeletal muscle stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Nat. Protoc. 10, 1612–1624. doi:10.1038/nprot.2015.110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Luo, T., Tan, B., Zhu, L., Wang, Y., and Liao, J. (2022). A review on the design of hydrogels with different stiffness and their effects on tissue repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 817391–817418. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.817391

留言 (0)