The superior mesenteric vein, inferior mesenteric vein, and splenic vein collect blood from the intestines, spleen, pancreas, and gallbladder, transporting it to the liver and forming the portal vein (PV) system. Most anomalies of the PV system are congenital, with the most common ones occurring in small vessels. Main trunk anomalies, such as duplicated PVs, congenital absence of the PV, and unbranched PVs, are relatively rare.[1] Computed tomography venography (CTV) imaging plays a crucial role in detecting abnormal vessels, clearly showing their origin, shape, and branching patterns. Accurately understanding these vascular variations is important for correct diagnosis and avoiding unnecessary surgeries. This article reports a new anomaly of the main PV trunk,[2] which we refer to as “three main portal veins.”

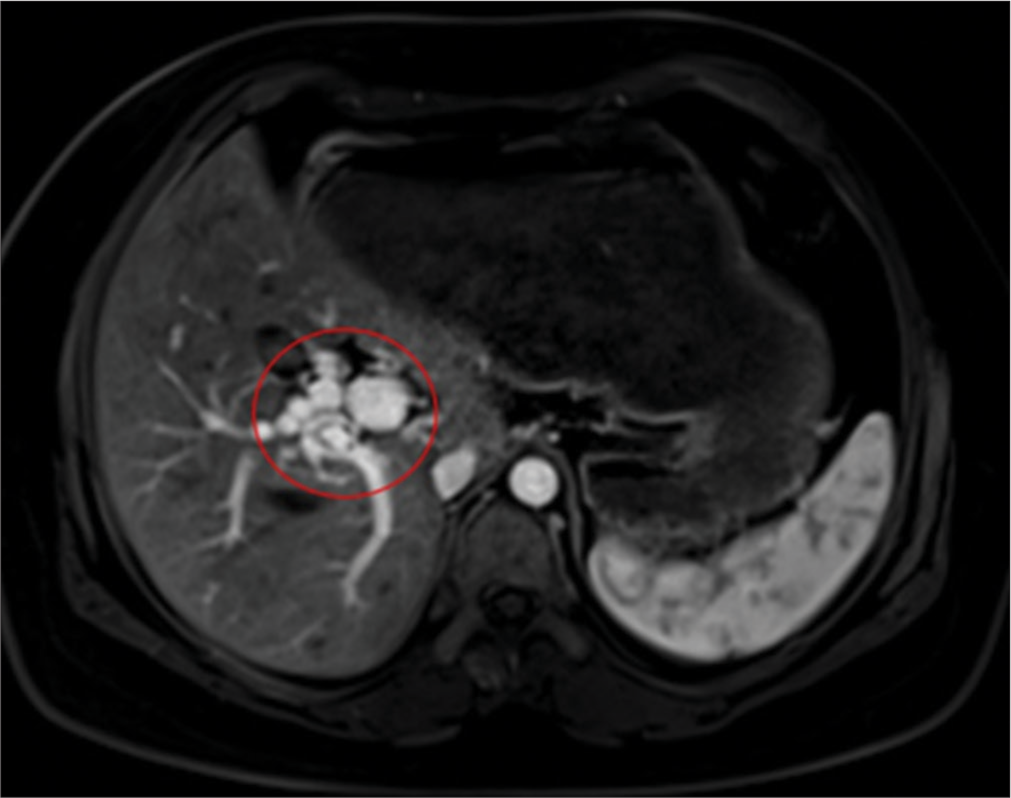

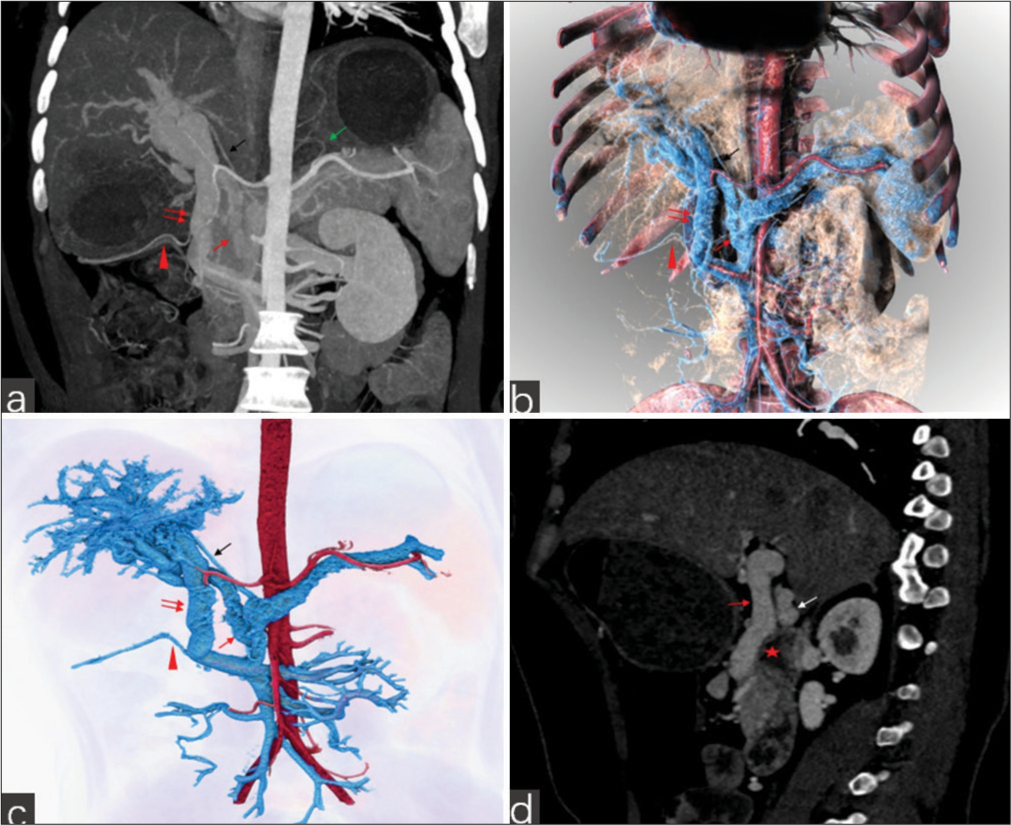

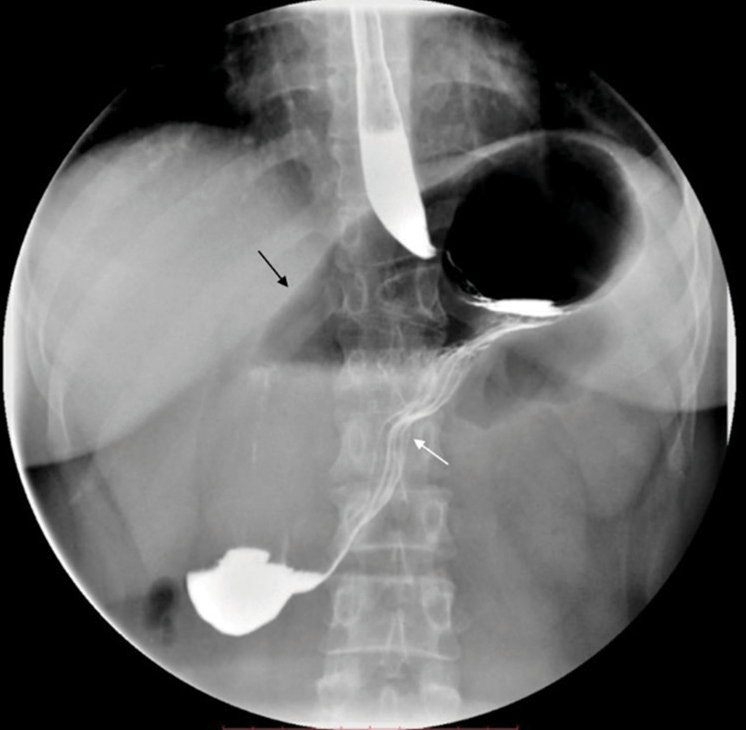

CASE REPORTThe patient, a 26-year-old female, presented with upper abdominal pain lasting more than 10 days. A previous gastroscopy revealed chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric retention. Deep palpation of the upper abdomen revealed tenderness without any mass. The initial clinical diagnosis was a gastrointestinal motility disorder. To rule out autoimmune liver disease, an enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI showed irregular PV thickness with multiple twisted vascular shadows around it and nodular abnormal signals in the hepatic portal area [Figure 1], suggesting hepatic sinusoidal dilation. Consequently, a CTV scan was performed for further vascular evaluation. The patient was initially misdiagnosed with PV cavernous transformation. A subsequent PV CTV examination [Figure 2] showed that three main PVs entering the liver, with no other pathways existed between these vessels. Due to the twisted course of the three vessels at the hepatic portal, the origin of the intrahepatic PV was indistinguishable. The origins of the right and left gastric veins were clearly aberrant. The patient’s condition improved after symptomatic treatment with acid suppression, and she was discharged. A year later, the patient was re-admitted with recurrent abdominal distention lasting more than 20 years, which had worsened for over a month. Examination revealed upper abdominal tenderness, and the preliminary diagnosis was gastrointestinal obstruction. The patient underwent a superior mesenteric artery computed tomography angiography to rule out superior mesenteric artery syndrome, but the imaging of the main PV anomaly remained unchanged. Concurrent gastrointestinal imaging suggested gastric volvulus [Figure 3], which was treated surgically. The patient recovered and was discharged, with no abnormalities detected in follow-up 1 year later. A literature search revealed no reports of PV anomaly combined with gastric volvulus.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONThe PV is a short, thick vessel, about 6–8 cm long, formed by the joining of the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein behind the pancreas. It ascends behind the upper part of the duodenum to the hepatic portal, where it splits into left and right branches, which further divide within the liver before emptying into the hepatic sinusoids. The PV carries blood from the digestive system, spleen, pancreas, and gallbladder into the liver.[3]

Previous reports suggest that duplicated PV anomalies can cause abdominal pain, portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and reduced hepatic fat,[4] with twisted PV pathways increasing the risk of thrombosis.[5,6] Early diagnosis and regular follow-up are essential to prevent serious complications such as PV thrombosis and portal hypertension.[2] However, in this case, the patient’s abdominal pain was due to incomplete gastric volvulus, with no signs of portal hypertension, varices, or hepatic fat, and no discomfort detected so far. The absence of symptoms in this case of PV anomaly may be attributed to two factors. First, the three main trunks of the PV converge after entering the liver, and the hemodynamics of the liver have not changed; thus, there are no manifestations of hepatic fat. Second, no PV thrombosis or liver function abnormalities were found, which did not lead to portal hypertension. However, the potential for thrombosis persists due to the presence of venous tortuosity in the hepatic hilum. Consequently, regular monitoring is essential to ensure the continued stability of the anomaly.

During embryonic development, the left and right gastric veins form and connect with the PV system between the 6th and 12th weeks.[7] The initial vascular structures appear between the 6th and 8th weeks, maturing between the 8th and 12th weeks, eventually establishing their anatomical positions and connections with the PV trunk.[8] This process ensures effective transportation of venous blood from the stomach and other digestive organs to the liver for metabolism. The stomach and PV system develop closely from the primitive gut and related vascular system. Therefore, anomalies in their development may share a common basis.[7,8] PV system anomalies may lead to abnormal blood flow to the stomach and surrounding tissues, affecting normal gastric development and rotation. These anomalies are often associated with congenital heart disease, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and congenital gastric ligament dysplasia.[7,8] In this case, the PV anomaly was combined with abnormal origins of the left and right gastric veins, with clinicians attributing the gastric volvulus to congenital chronic gastric volvulus causing incomplete gastrointestinal obstruction. Thus, we speculate that PV anomalies and abnormal left and right gastric veins may be related to congenital chronic gastric volvulus, manifesting clinically as complex abdominal symptoms.

Our case was initially misdiagnosed as PV cavernous transformation during MRI because the twisted blood vessels of the three main PVs at the hepatic portal were mistaken for collateral circulation. PV cavernous transformation results from partial or complete blockage of the main PV and its branches, leading to the formation of collateral circulation to reduce pressure around the PV. Clinically, it often presents with gastrointestinal symptoms such as hematemesis, melena, splenomegaly, and hypersplenism, and occasionally jaundice and ascites.[9] Imaging shows disordered, thickened, and irregular vascular shadows at the hepatic portal. PV anomalies are rare and varied, with complex shapes and courses of abnormal vessels. Computed tomography scans with multiplanar reconstruction, maximum intensity projection, and volume rendering post-processing can visually display variant vessels, reducing missed and misdiagnoses, thus playing an important role in diagnosing PV anomalies.

Reports of intraoperative findings of PV variations are increasing and they all emphasize that accurately recognizing these variations preoperatively is crucial for surgical success.[10] Our patient underwent surgery for gastric volvulus, with pre-operative CTV examination identifying these variations and facilitating the recognition of gastric vascular anatomy, aiding surgery.

In addition, rare PV anomaly needs to be differentiated from portal cavernoma, which are characterized by localized dilatation of the PV. The anomaly commonly occurs at the confluence of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein, or at the bifurcation of the PV. It can be classified into intrahepatic and extrahepatic types based on their location. It is crucial to identify these kinds of anomalies especially before liver transplant and other surgeries needing vein reconstruction.[11]

CONCLUSIONVariations in the main PV trunk are rare. This case represents a new type of PV anomaly, aiming to enhance the awareness and understanding of PV duplication anomalies among clinical and imaging physicians. Understanding these rare variations is crucial for clinicians to make accurate diagnoses and treatment plans.

留言 (0)