Pulmonary sequestration is a rare congenital lung malformation characterized by nonfunctioning lung tissue without communication with the tracheobronchial tree and instead receives blood supply from non-pulmonary systemic arteries. This anomaly makes up 0.15–6.4% of all congenital pulmonary malformations and are classified as extralobular and intralobar.[1] Extralobular sequestrations have distinct pleural covering and venous drainage, typically presents in the first 6 months of life, are less common, and often co-occur with other congenital abnormalities.[2] Intralobar pulmonary sequestrations are contiguous with normal lung, can present at any age, and can be acquired or congenital. In the former, the malformations may result from antecedent infection or bronchial obstruction with the isolated lung then developing accessory arterial supply from the aorta.[3] About one-third of bronchopulmonary sequestrations are identified in childhood and are typically asymptomatic – discovered incidentally through imaging. Adult diagnoses are almost always symptomatic and most commonly present in the 4th decade.[3] In these cases, infection is seeded into the sequestered lung tissue through interalveolar connections from adjacent normally aerated lung.[4] With no ability to clear infection through mucociliary escape, infection becomes trapped in the sequestered lung leading to cycles of infection and inflammation – commonly cough and hemoptysis.

There are currently no consensus treatment guidelines.[5] In adults, video-assisted thoracoscopic treatment is the most common approach,[6] though there has been in increase in treating sequestrations with minimally invasive embolization of the feeding artery.[7-9] In addition, pulmonary sequestrations have also been reported to regress spontaneously and, thus, may contribute to its low prevalence in adults.[10]

We describe the management of three adult patients with intralobar pulmonary sequestrations who were treated with transcatheter embolization.

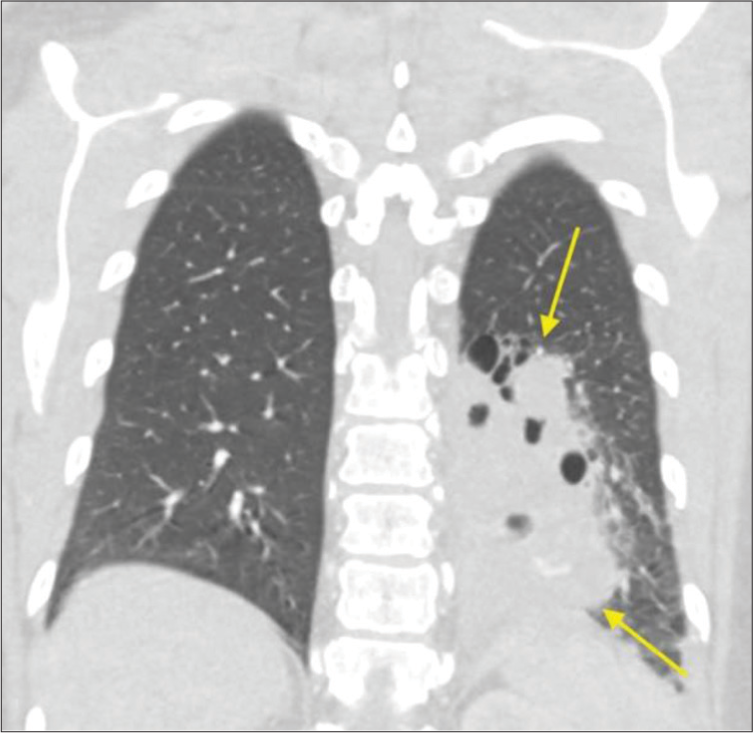

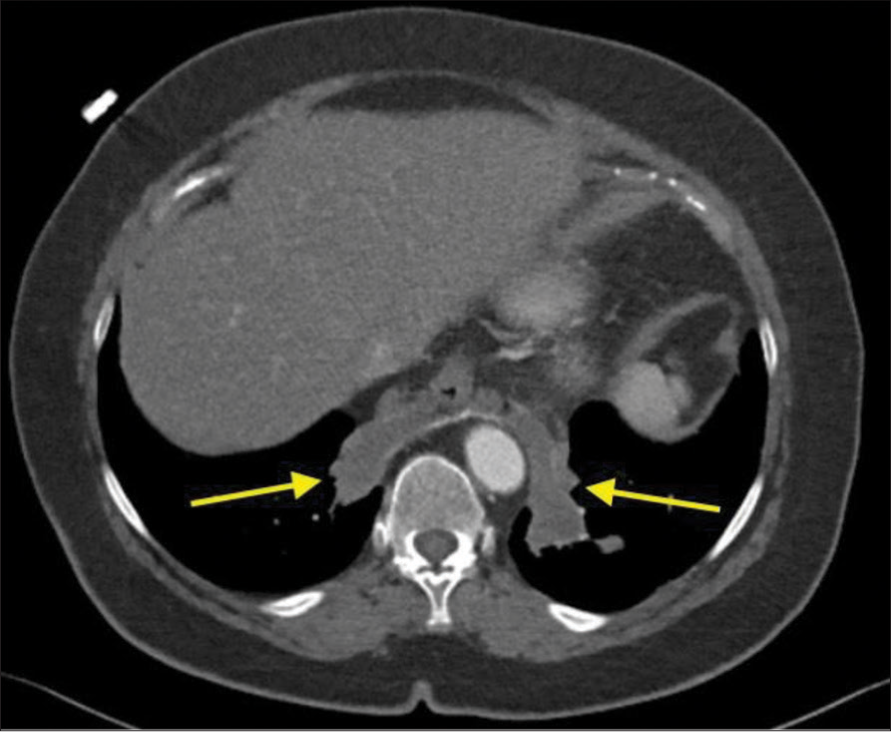

CASE SERIES Case 1A 53-year-old female with a history of coronavirus pneumonia 7 months earlier presented to the emergency department with cough, shortness of breath, and back pain. She was tachycardic with a low-grade fever and mild leukocytosis. She reported pain with coughing that was ongoing for several years with recent exacerbation. She denied prior chest surgery or smoking history and was an active individual with a recent notable decrease in exercise tolerance. A chest computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.3 × 7.0 × 9.6 cm heterogeneous rounded complex mass in the left lower lobe with multiple air-fluid levels and a vascular supply directly from the adjacent descending thoracic aorta [Figure 1]. These findings were consistent with sequestered pulmonary parenchyma with superimposed infection. The patient was discharged, referred to thoracic surgery and interventional radiology (IR), and was agreeable to pre-operative embolization; initially planned for debulking and hemostatic control for possible subsequent operative intervention.

Export to PPT

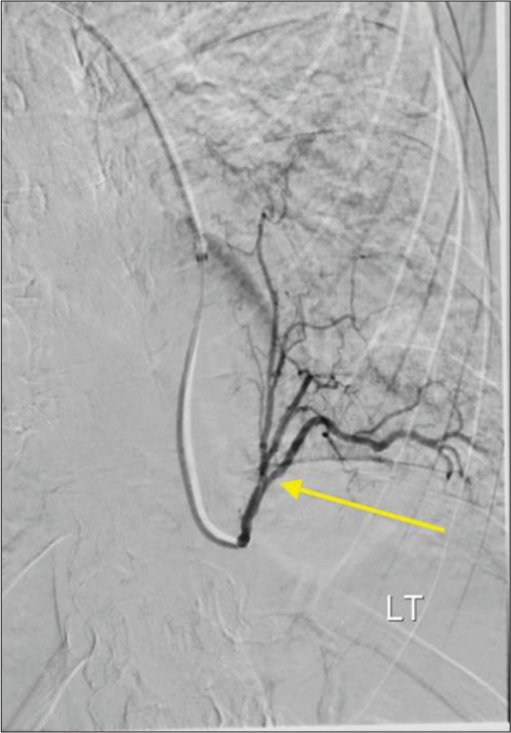

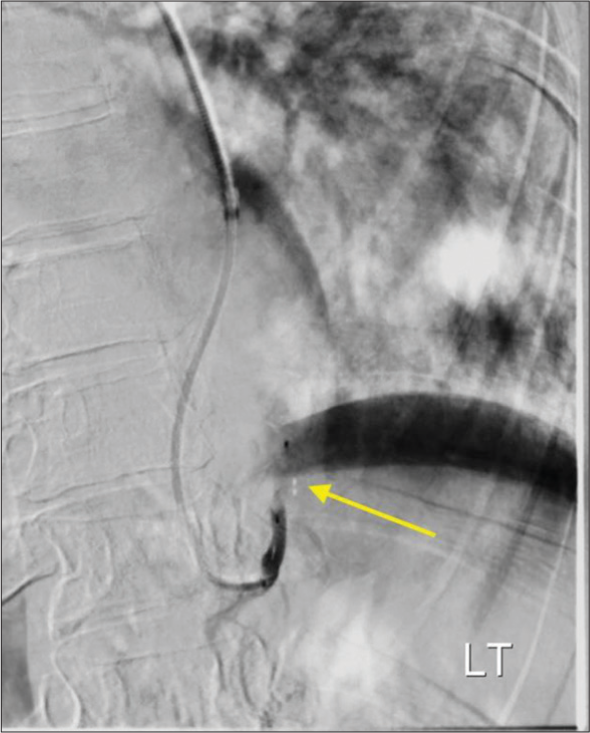

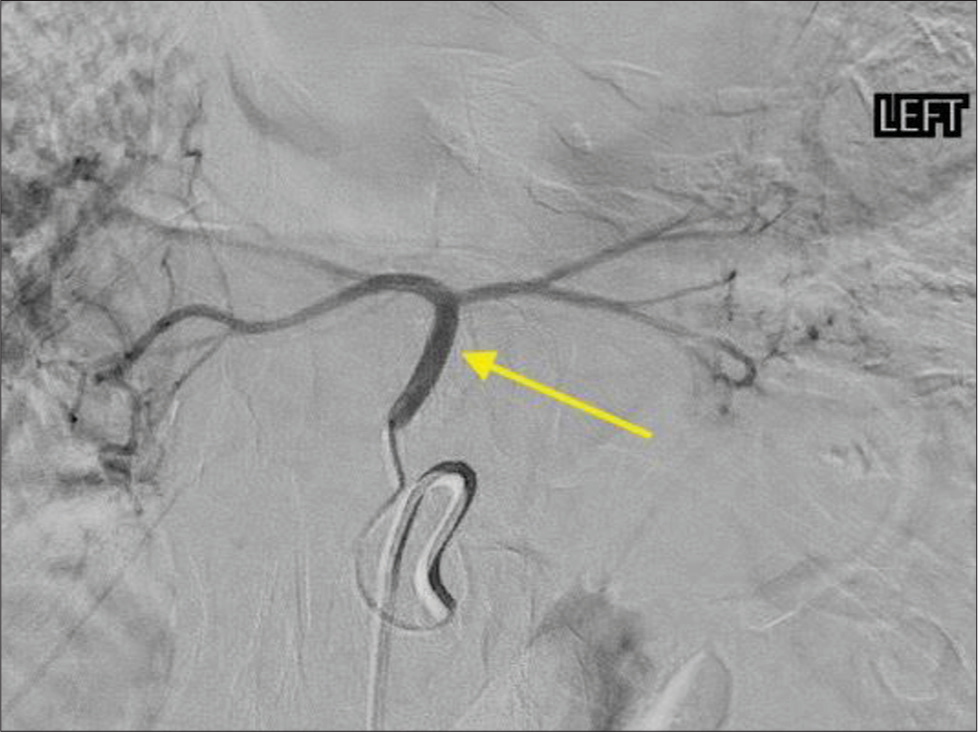

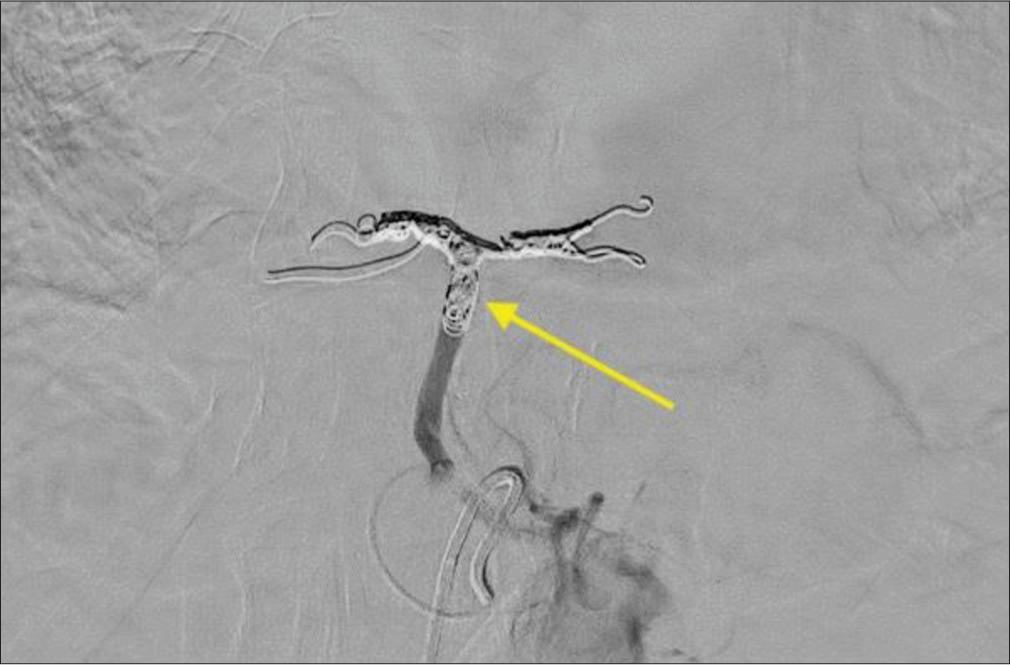

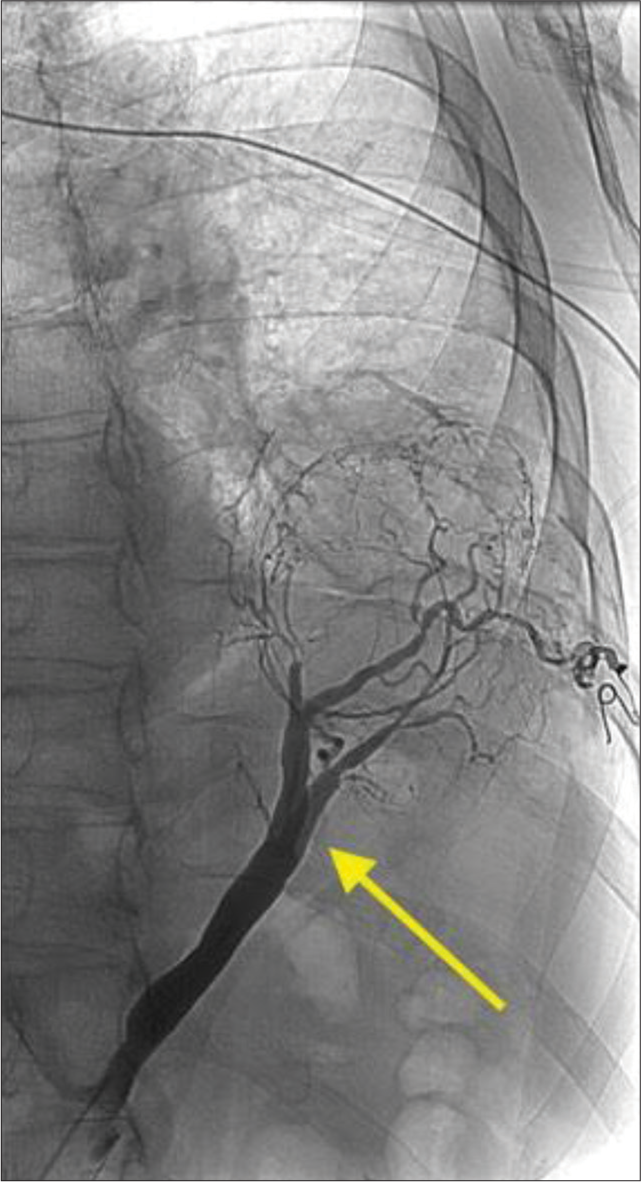

The procedure was performed under moderate sedation with radial artery access. Digital subtraction angiography of the aorta and selective angiography of first and second-order branches of the aorta supplying the pulmonary sequestration were obtained [Figure 2]. The anatomy was favorable for proximal embolization and a single Low-profile Braided Occluder (LOBO)-3 (Okami Medical, Aliso Viejo, CA) occlusion device was deployed in the first-order branch of the aorta supplying pulmonary sequestration [Figure 3]. Completion angiogram confirmed stasis and no further flow to the pulmonary sequestration was seen.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

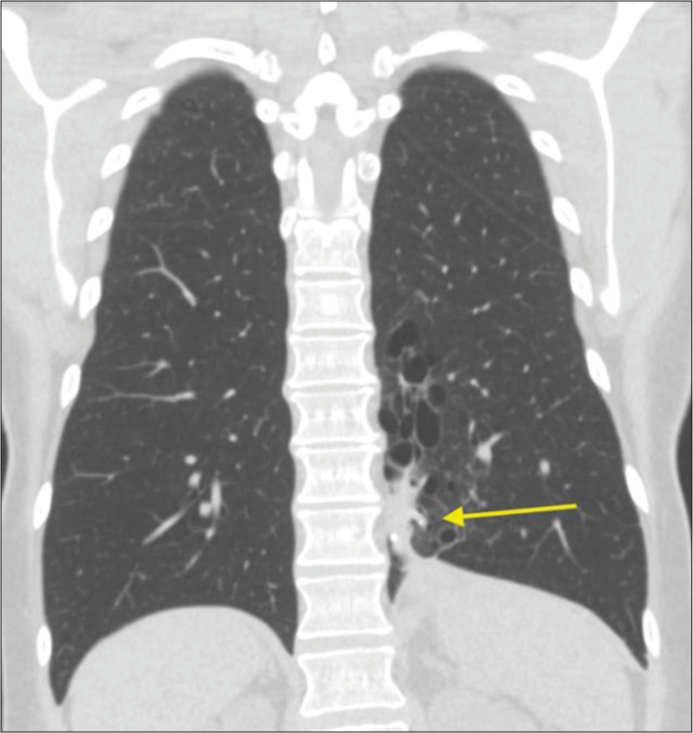

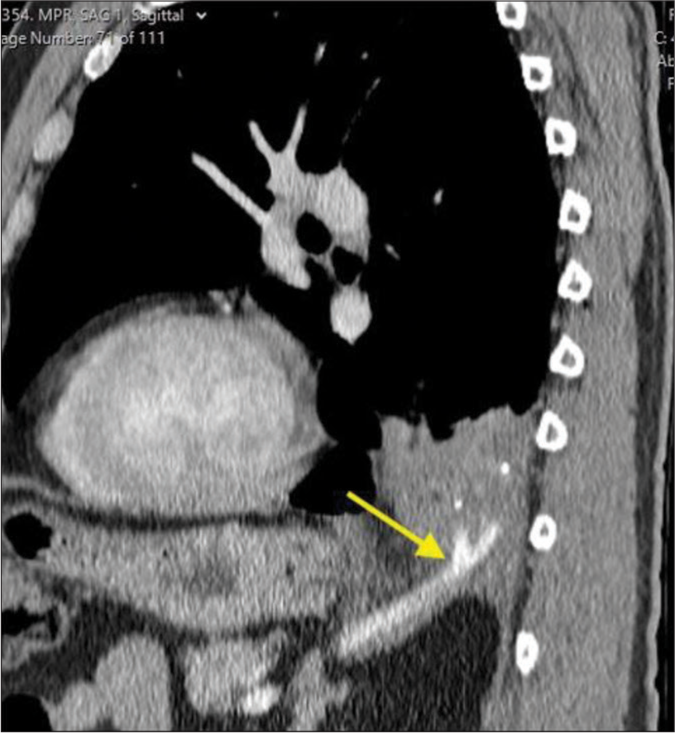

One month follow-up chest CT showed approximately 50% volume reduction of the sequestered lung with decreased surrounding inflammatory changes. Subsequent follow-ups continued to show improvement and at 9 months post-procedure, the region of pulmonary sequestration measured 1.5 × 2.2 × 3.1 cm [Figure 4]. The patient reported complete resolution of her shortness of breath, pain, and coughing. She continued to do well and did not require surgical intervention.

Export to PPT

Case 2A 70-year-old female with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, and 15-year history of a chronic, dry cough presented with progressive coughing episodes that resulted in bouts of hemoptysis. The patient had previously been treated for bronchitis, asthma, and reflux disease in the past. At least, two non-contrast chest CT examinations had been performed demonstrating bibasilar consolidation. The patient developed worsening hemoptysis and a contrast-enhanced CT of the chest was performed in planned evaluation of the bronchial arteries. The examination resulted in an unanticipated finding of systemic arterial supply to the basilar consolidations [Figure 5]. This allowed for a diagnosis of bilateral intralobar sequestration. After a multispecialty discussion, it was determined that an arterial embolization using an endovascular approach was the safest initial treatment.

Export to PPT

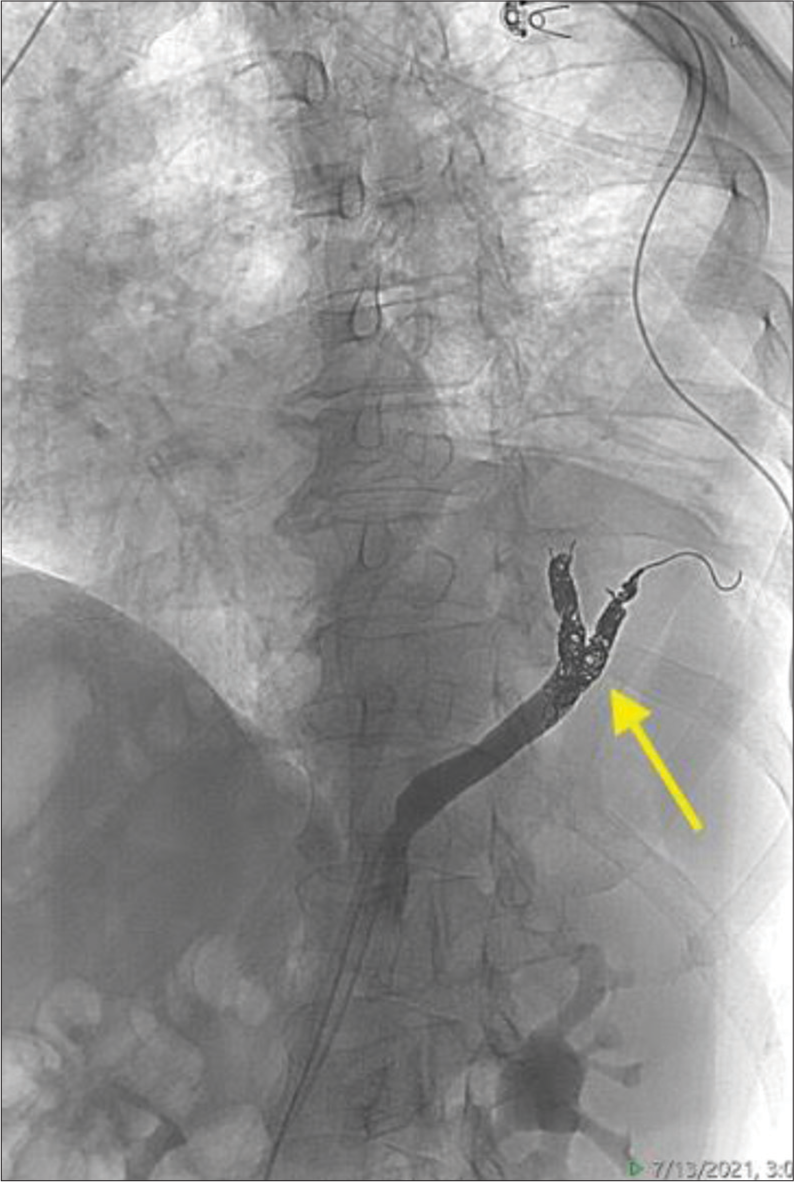

The procedure was performed with moderate sedation using common femoral artery access. The common arterial trunk arose from the left gastric artery and the bifurcating left and right segmental branches [Figure 6] were embolized using 4 mm Concerto detachable coils (Medtronic, Fridley, MN). The coil pack was then extended proximally to embolize the common trunk with 6 mm coils [Figure 7]. The angiographic endpoint was flow stasis. The patient was discharged on the same day of the procedure after a 2-h recovery.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

At 4 months, a CT angiogram was performed demonstrating no parenchymal enhancement of the sequestration. At 5 months, the patient reports being asymptomatic with resolved cough, no new episodes of hemoptysis, and improved breathing.

Case 3A 70-year-old male with known left lower lobe pulmonary sequestration presented with sub-massive hemoptysis. On presentation, he was hemodynamically stable, with a hematocrit of 39%, previously 43% 2 months ago. He had mild subjective dyspnea, but oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. Initial CT revealed an aberrant branch from the aorta supplying the sequestration, without any other contributing supply [Figure 8]. Thoracic surgery was consulted for resection and IR was consulted for embolization. A multi-disciplinary approach of urgent embolization followed by medical optimization and subsequent resection in the short term was agreed on.

Export to PPT

Arterial access was obtained through the right common femoral artery. An aortagram was performed which demonstrated a large aberrant artery arising from the aorta at the level of the celiac axis. First-order branches of this vessel were selected [Figure 9] and coil embolization was performed with multiple detachable Ruby Coils (Penumbra Inc., Alameda, California) up to the confluence, to allow enough room for cross-clamp and resection during eventual surgical resection [Figure 10]. Post-embolization angiogram through both the microcatheter and the parent catheter demonstrates occlusion of the culprit vessel.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

The patient’s hemoptysis resolved overnight, with stabilization of hematocrit. He was discharged 4 days after presentation. Definitive surgical resection was performed 9 weeks later by thoracic surgery.

DISCUSSIONPulmonary sequestration is a rare congenital lung malformation. Although it can be an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients, it is also associated with serious complications such as massive hemoptysis, recurrent respiratory infections, and heart failure. As a result, the treatment for symptomatic patients has historically been surgical resection.[11] A possible cause for low adult prevalence of pulmonary sequestration is due to the evidence of spontaneous regression.[12] This is thought to be the result of progressive fibrosis of the dysplastic lung tissue and feeding blood vessel which eventually results in thrombosis and infarction.[13] A transcatheter embolization technique takes advantage of this mechanism by occluding the arterial supply, leading to infarction of the sequestration. Although there is currently limited literature describing endovascular management for pulmonary sequestration, this creates room for conversation regarding the optimal management for these patients.

As the above cases demonstrated, endovascular treatment can be performed through femoral or radial arterial access. Depending on the patient’s anatomy, a variety of catheters can be used to allow for selective and superselective angiography. Once at the vessel of interest, the operator’s choice of embolic can be deployed to achieve total occlusion. Here, we have demonstrated use of plugs and endovascular coils, though there is evidence of case reports which have utilized embolic agents such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles, gelfoam, and glue in addition to coils and plugs.[7-9] Final angiography is necessary to confirm total occlusion and follow-up imaging can be obtained to track the size of the pulmonary sequestration over time.

Embolization has been reported to be effective in pediatric cases with a low complication rate; however, repeat embolization may be required for some patients. Long-term follow-up for pulmonary sequestration post-embolization is limited; however, the imaging findings presented here suggest that it may be an effective and definitive treatment in patients with amenable anatomy and targetable arterial supply. Potential limitations of transcatheter embolization include contrast usage, relative contraindication in patients with kidney failure, and radiation exposure, though this is thought to be less of a concern in adult patients. Advantages of this approach include its minimally invasive nature which does not necessitate hospitalization or general anesthesia, and rapid recovery time. Potential complications include non-target embolization, for which, meticulous angiographic techniques should be deployed. Although there are currently no randomized control trials to compare patient outcomes after embolization versus surgical resection, these cases further supports existing case series that suggest the efficacy of this minimally invasive approach for patients with this disease process. Further, investigation directly comparing this angiographic approach to surgery may be limited due to the prevalence of the disease process. Given multiple potential embolization strategies, these cases suggest that definitive proximal embolization of the feeding vessels may be an effective treatment strategy that warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSIONProximal arterial embolization of pulmonary sequestration may be a safe, effective, and durable minimally invasive treatment for adults with symptomatic pulmonary sequestration, and possibly negate the need for surgery. Further, investigation may help clarify the best mode of embolization as well as compare outcomes with surgical resection.

留言 (0)