Meningiomas are the most common extra-axial broad-based non-glial tumors of the central nervous system (CNS). Meningiomas originate from the arachnoid membrane that envelops the brain, nerves, and spinal cord. They are frequently observed in individuals over 50 years, with a prevalence of 2–3% among the elderly population.[1] While most meningiomas develop spontaneously with an unknown cause, certain recognized risk factors include prior exposure to radiation and genetic disorders, such as neurofibromatosis type 2.[2] Most commonly, meningiomas are asymptomatic, although clinical signs may vary and arise from the compression of brain structures or obstruction of the ventricular system. Meningiomas predominantly occur along the lateral hemisphere convexity (20–34%), parasagittal (18–22%), sphenoid wing, middle cranial fossa (17–25%), and olfactory groove. Less common sites include cerebellopontine (CP) angle (2–4%), intraventricular (2–5%), orbital (<1–2%), clivus (<1%), and ectopic areas such as optic nerve sheath (0.4–1.3%) and choroid plexus (0.5–3%). Histopathologically, while the spinal origin accounts for about 10%, approximately 90% of meningiomas are classified as World Health Organization (WHO) Grade 1 lesions, denoting a benign nature. However, a minority, comprising 5–7%, exhibits atypical features as WHO Grade 2 tumors, while an even smaller fraction, ranging from 1% to 3%, represents the more aggressive WHO Grade 3 anaplastic types. It is important to recognize both the atypical locations and unusual imaging features of these common neoplasms to avoid misdiagnosis.

Imaging findingsThe role of plain films in diagnosing meningiomas has largely been replaced by more advanced imaging techniques. While most plain films appear normal, they can occasionally reveal hyperostosis, calcification, or osteolysis associated with meningiomas.

Meningiomas typically present as well-defined, lobulated extra-axial masses with broad-based dural attachment. They may cause inward displacement of cortical gray matter and occasionally display an infiltrative “meningioma en plaque” growth pattern.[3]

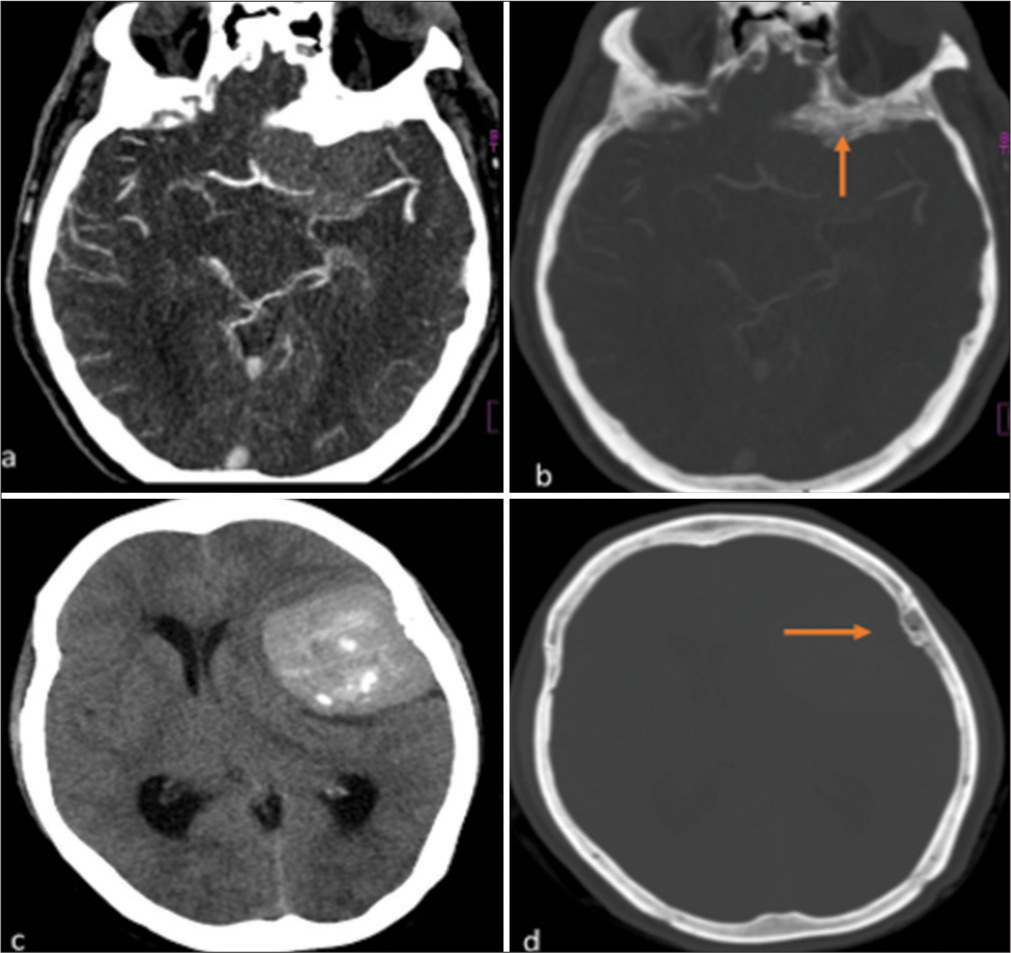

Computed tomography (CT) is often the initial imaging method for detecting meningiomas. CT scans are particularly effective at visualizing the tumor and its related features, including calcification, hemorrhage, edema, and changes in the calvarium. On unenhanced CT, meningiomas typically appear as sharply defined, homogeneous, and hyperdense extra-axial masses with a broad dural attachment.[4] In only 1–2% of cases, multiple tumors are present. About 60% of meningiomas appear as hyperdense solid lesions, and up to 20% show calcification. Enhancement with intravenous contrast medium is intense and usually homogeneous. Bone changes associated with meningiomas primarily include osteolysis and hyperostosis, with hyperostosis being the most common, occurring in approximately 20% of cases, particularly in the en plaque form.[3] These changes are best visualized on CT, although they can also be detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Hyperostosis frequently occurs in tumors located at the skull base and anterior cranial fossa, and its extent is not necessarily related to the tumor size [Figure 1]. Pathologically, hyperostosis may result from[4] direct tumor invasion of the bone or reactive hypervascularity of the periosteum, leading to benign bone formation.[5] Distinguishing between hyperostosis due to en plaque meningiomas and primary intraosseous meningiomas, especially osteoblastic types (seen in 59% of cases), can be challenging, particularly when the latter is accompanied by underlying dural enhancement. However, homogeneous, dense enhancement of the tumor within the skull can help differentiate a primary intraosseous meningioma from an en plaque meningioma.

Export to PPT

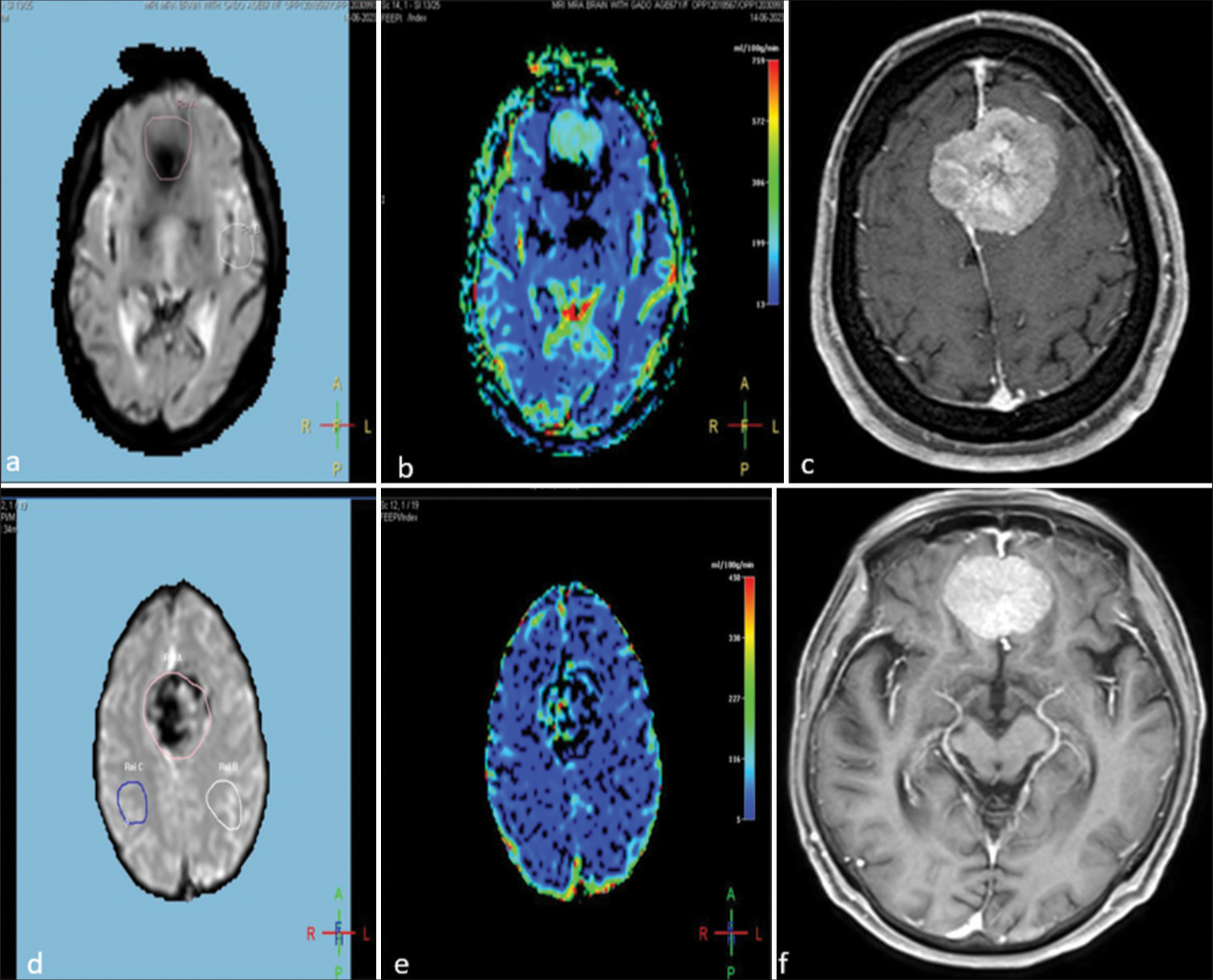

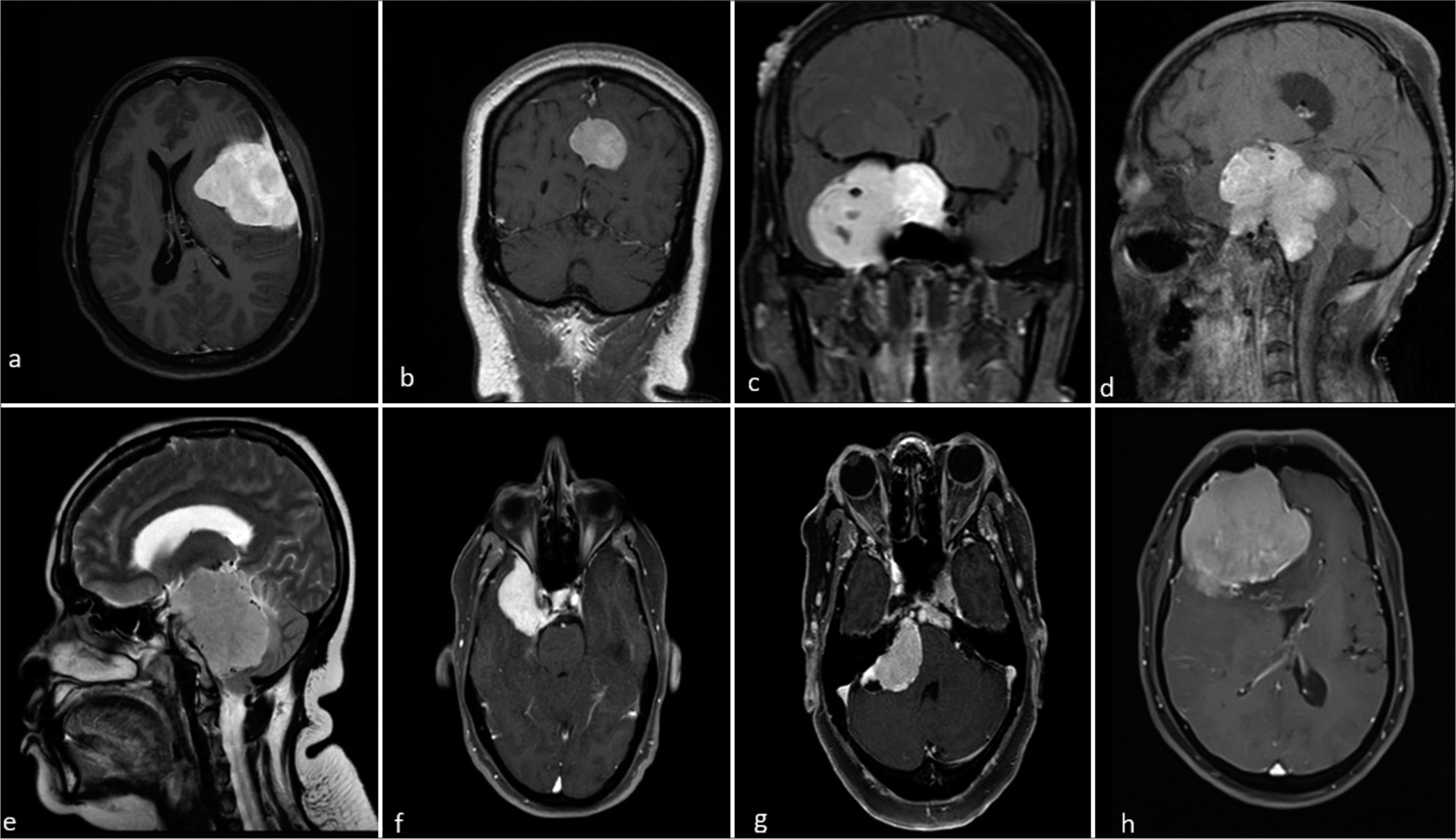

On MRI, they appear iso to slightly hypointense on T1 and isointense to slightly hyperintense on T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, with varying diffusion restriction. Post-contrast, meningiomas usually show avid, homogeneous enhancement, but may have non-enhancing areas such as necrosis or calcification. A dural tail is present in approximately 72% of cases, and a cerebrospinal fluid cleft is characteristic due to its extra-axial location.[6] Encasement of arteries and veins is common, and bone involvement, seen in 20% of cases, can lead to hyperostosis or lytic destruction. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) findings in meningiomas are mostly non-specific. Alanine detection inconsistency and lipid presence (0.9/1.3 ppm) are not always reliable indicators of aggressive meningiomas or conclusive evidence of non-benign meningiomas due to variability in results.[7] Meningiomas are highly vascular lesions, typically exhibiting hyperperfusion on perfusion-weighted imaging, with dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI being the most commonly used technique [Figure 2]. Relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) is generally elevated, with reported values ranging from 6 to 9. Angiomatous subtypes tend to have slightly higher rCBV values, while fibrous subtypes may show slightly lower values.

Export to PPT

Meningiomas are highly vascular tumors, often showing a significant tumor blush and delayed washout on catheter angiography. They are primarily supplied by meningeal branches of the external carotid artery, with additional supply from the internal carotid or vertebral arteries, and sometimes pial vessels. These tumors can encase or displace major vessels and may occlude large veins and cerebral venous sinuses. Identifying these vascular features preoperatively is crucial to reduce the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage or postoperative infarction due to vascular damage.

MATERIAL AND METHODSA retrospective review was conducted on 82 patients with pathologically confirmed meningiomas who underwent both CT and diffusion-weighted MRI (1.5T) at our institution. The imaging data were analyzed to assess various parameters, including age incidence, sex distribution, tumor location, T1- and T2-weighted sequences, contrast enhancement patterns, and the presence of calcifications, cysts, peritumoral edema, hemorrhage, and MRS findings.

RESULTSThis study analyzed 82 surgically treated intracranial meningioma cases using MRI. It focused on age incidence, gender distribution, tumor location, T1 and T2 characteristics, contrast enhancement, calcification, cysts, peritumoral edema, hemorrhage, and MRS findings.

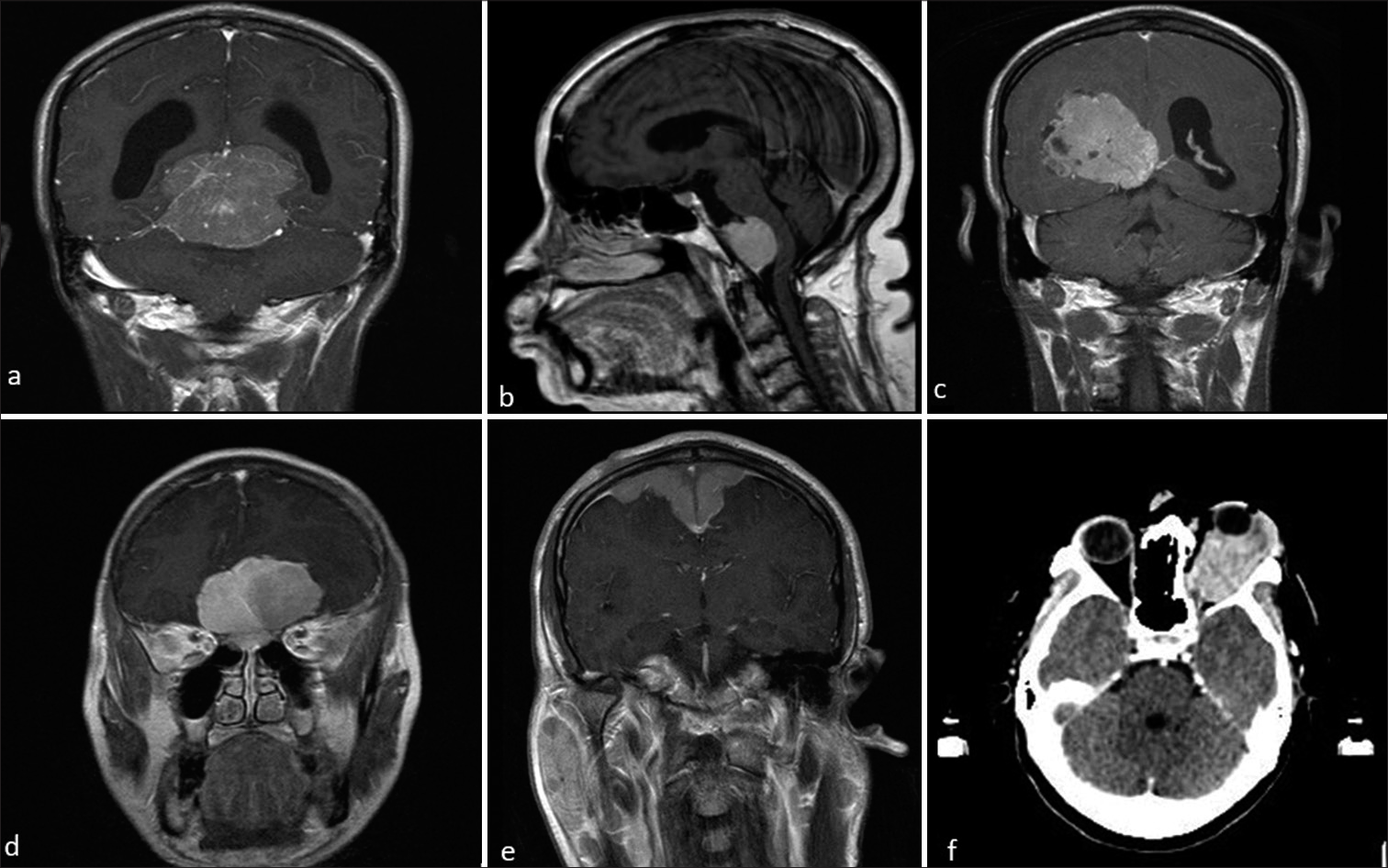

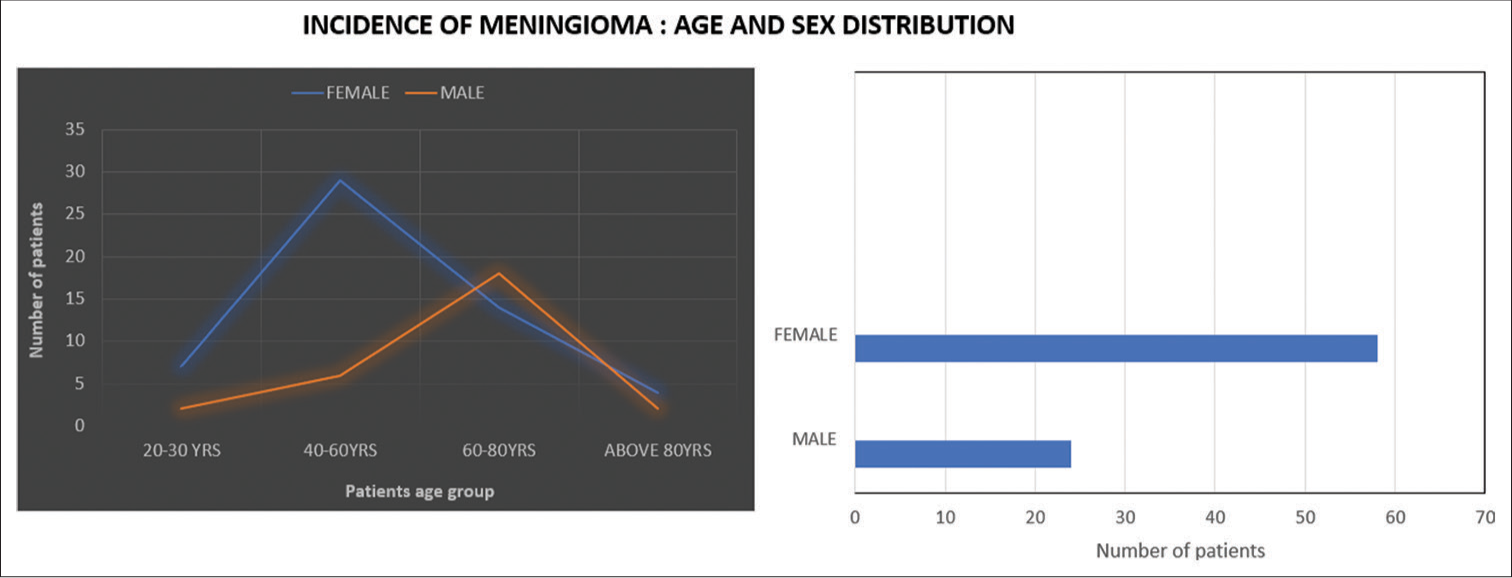

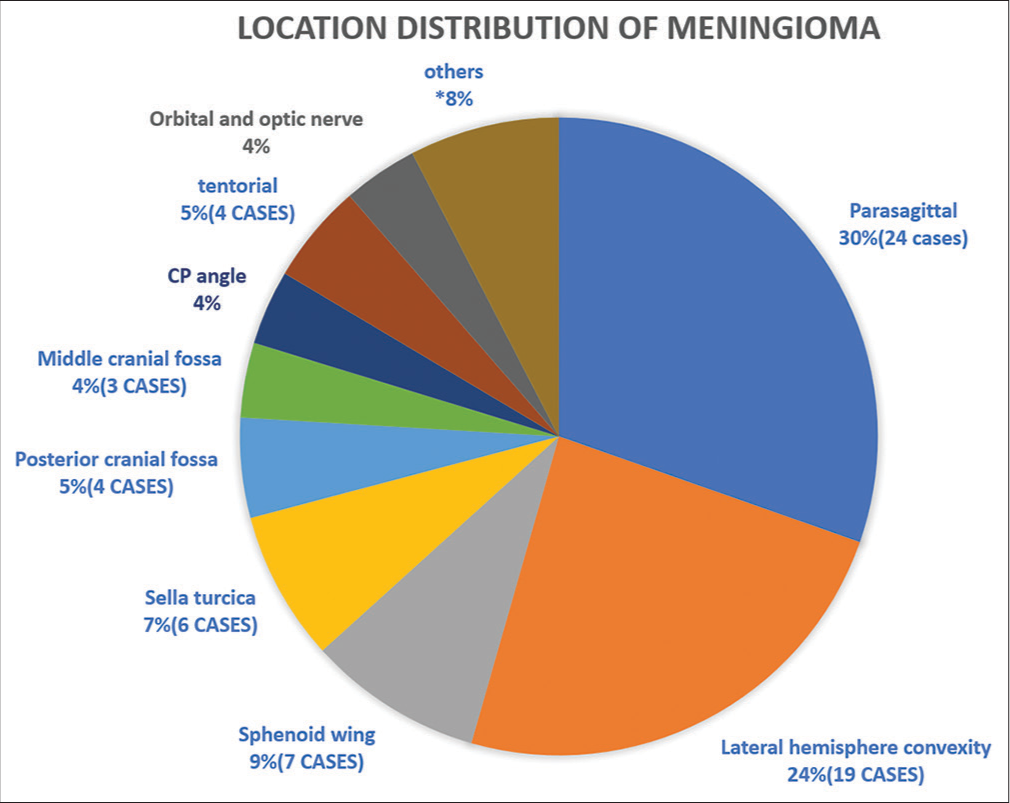

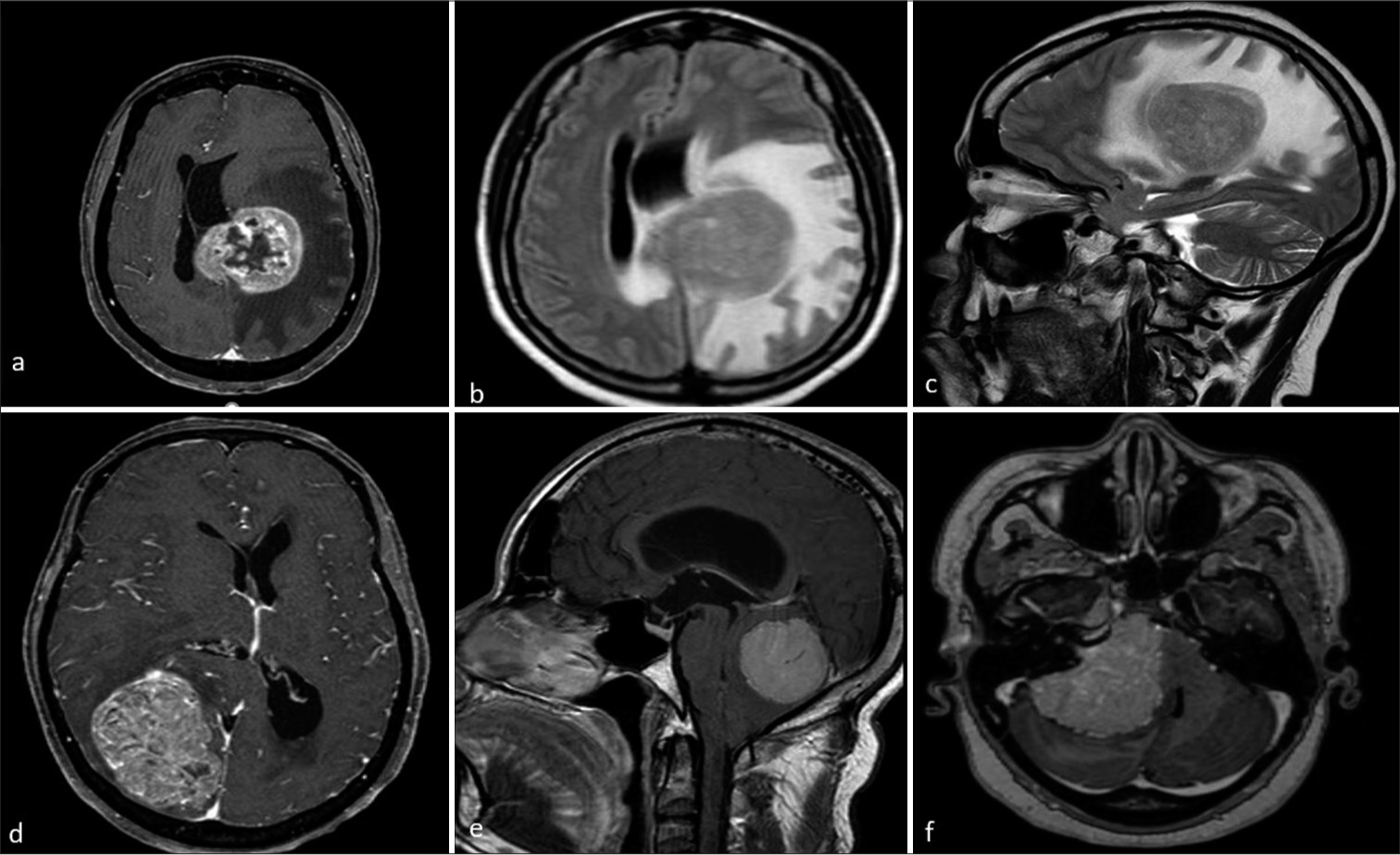

Meningiomas occurred in individuals aged 21–84, peaking at 40–60 for females and above 60 for males [Graph 1]. The tumors are more common in female patients 58 out of 82 and the rest are male. Left-sided cases numbered 48, right-sided 34. Parasagittal tumors (30%) and lateral hemisphere convexity were predominant locations, aligning with existing literature [Pie Chart 1, Figures 3 and 4].

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

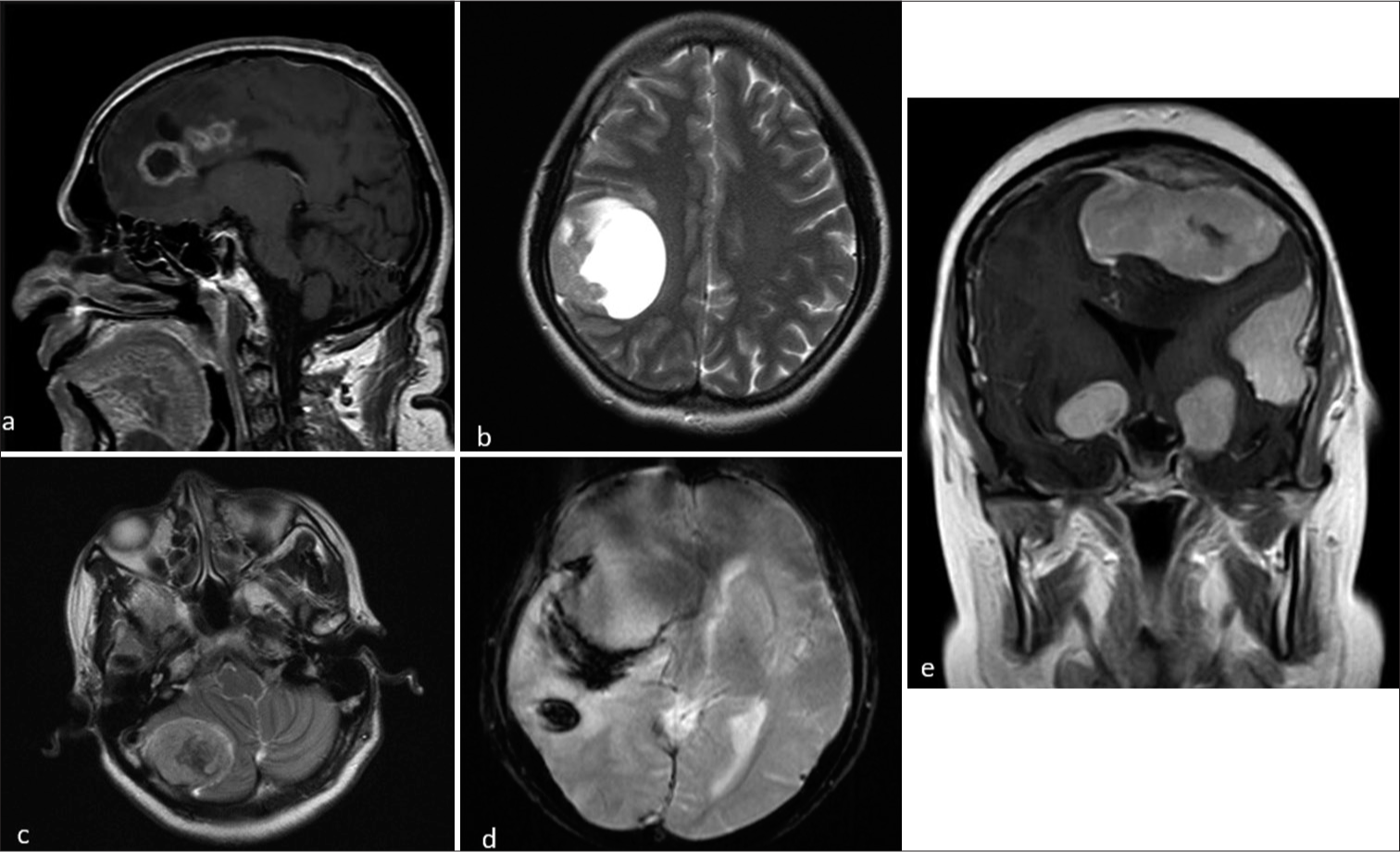

Most tumors showed typical magnetic resonance signal intensities and homogeneous contrast enhancement. Atypical features (22 cases) included heterogeneous signal, calcification, diverse contrast patterns, cysts, and necrosis. Dural tail signs and peritumoral edema occurred in over one-third of cases. Hyperostosis (24 cases) surpassed osteolysis. MRS indicated increased choline and creatine peaks, and alanine presence in 12 cases. Six cases had intratumoral/peritumoral hemorrhage; one had spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, confirming an anaplastic subtype. Encasement of carotid arteries and dural sinuses occurred in six cases. Four patients had recurrent meningiomas, and one case each of plaque meningioma and falx/tentorium origin was identified [Table 1, Figures 5 and 6]. Age, sex, location, and salient features of different cases given below.

Table 1: List of salient features of meningioma.

Findings Number of cases Peri-tumoral edema 38 Mass effects 31 Dural tail sign 27 Necrosis 21 Bone hyperostosis/erosion 21 Cystic changes 10 Abnormal MR spectroscopy 12 Intra/peritumoral hemorrhage 6 Vascular encasement 6 Calcification 4

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

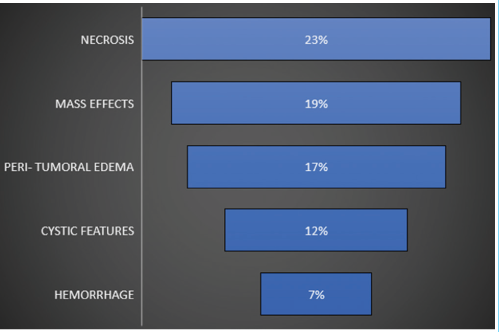

Atypical imaging featuresDistinguishing atypical meningiomas from the WHO I meningiomas before treatment is crucial for surgical planning and better outcomes. Atypical meningiomas show robust but heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Key imaging features include restricted diffusion, notably lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) compared to typical meningiomas. Perfusion MRI may reveal elevated rCBV, especially in peritumoral edema. MRS often indicates elevated alanine levels, a distinctive marker for atypical meningiomas. Recognizing these features is essential for accurate pre-treatment classification, guiding surgeries, and improving overall treatment success.[8] Prevalence of atypical imaging features in this study given below [Table 2]. Meningiomas from atypical locations are seen to have atypical features compared to typical locations [Table 3].

Table 2: Prevalance of atypical imaging features in this study.

Table 3: Meningiomas from atypical locations are seen to have more incidence of atypical features of meningioma compared to meningioma in typical locations.

Location Necrosis Hemmorhage Cystic changes Peri-tumoral edema[severe] Parasagittal[24] 6 2 4 5 Lateral hemisphere convexity[19] 3 - 2 2 Sphenoid wing[7] 2 - 1 1 Sella turcica[6] 3 2 1 1 Posterior cranial fossa[4] 2 - 1 1 Middle cranial fossa[3] 1 1 - - CP angle[3] 2 - - 1 Tentorial[3] 1 - 1 1 Others 1 1 - 1X-Axis (Age Groups): The current grouping of ages into broader intervals (e.g., 20-40 years, 40-60 years) was chosen to maintain clarity and readability given the sample size in each group. While we considered more granular intervals, the existing groupings reflect meaningful stages in patient age distribution and allow for a more streamlined comparison between age groups. We believe this format effectively communicates the trends in the data. Y-Axis (Number of Patients): The y-axis intervals were selected based on the maximum value of patients (35) in the dataset. To avoid unnecessary complexity, we used consistent increments of 5, which we believe balance accuracy and simplicity. We opted not to extend the y-axis beyond 35, as this would create empty space without additional informative value.

DISCUSSIONMore than 80% of meningiomas fall into the meningothelial, fibrous, and transitional subtypes, classified as WHO Grade 1, exhibiting typical imaging features described earlier. However, a smaller subset labeled as WHO Grade 2 and Grade 3 meningiomas displays distinct and atypical imaging findings.[7]

Meningothelial meningiomas, the most common subtype, typically present with hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences, homogenous contrast enhancement featuring a dural tail sign, and associated bone hyperostosis. Fibrous meningiomas, characterized by collagen presence, show relative T2 hypointensity. Transitional meningiomas exhibit mixed iso- and hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences. Psammomatous meningiomas, besides typical features of the WHO Grade 1, are distinguished by calcifications. Angiomatous meningiomas showcase multiple flow voids due to hypervascularity, accompanied by significant peritumoral edema. Reticular type contrast enhancement with peritumoral edema characterizes microcystic meningiomas.

Secretory meningiomas, common at the skull base, display high-signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences with high ADC values, unlike typical meningiomas, along with notable peritumoral edema. Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningiomas in young patients present with irregular tumor margins invading adjacent brain tissue, displaying heterogenous contrast enhancement and significant peritumoral edema. Clear cell meningiomas, mainly seen in young patients at CP angles, often recur. Their MRI features include heterogenous contrast enhancement, cysts, peritumoral edema, and lytic bone destruction.

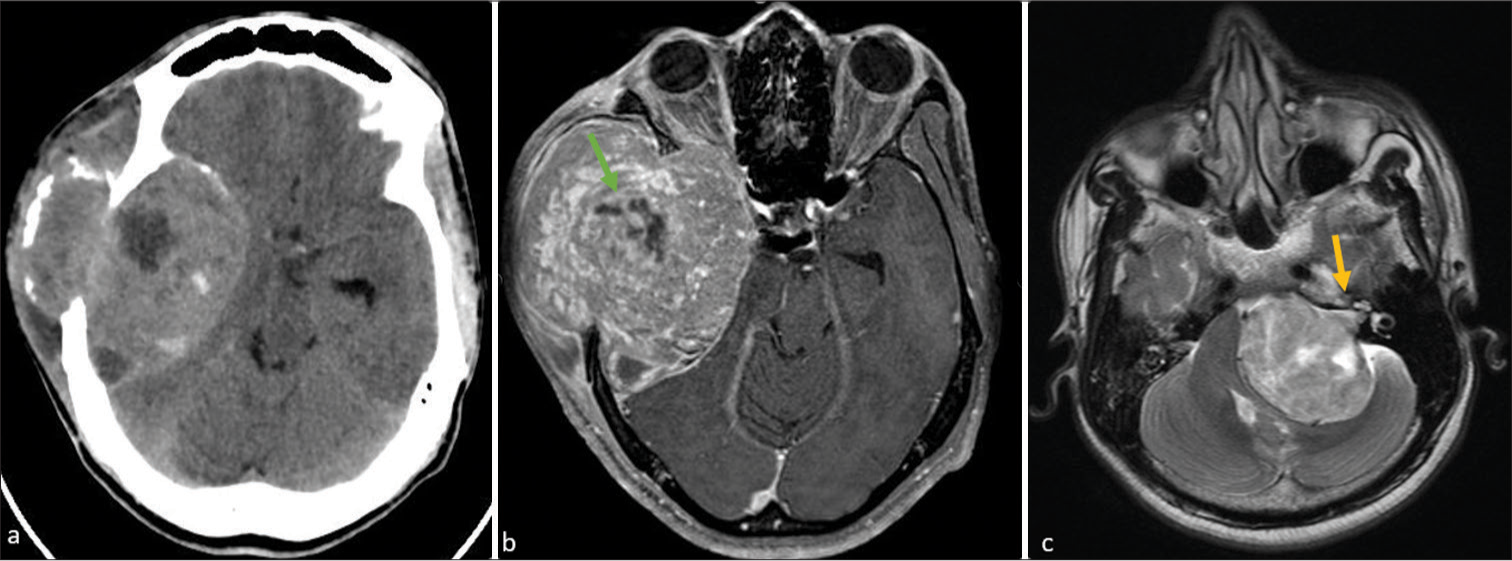

Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, more common in males, demonstrate irregular tumor margins, an indistinct tumor-brain interface, heterogenous signal intensities, restriction on diffusion-weighted sequences, underlying bone destruction, peritumoral edema, necrosis, and calcification.[7,9] Metaplastic meningiomas, containing cartilaginous, osseous, or lipomatous tissue, present varied imaging findings based on tumor composition. Although approximately 60% of meningiomas are extra-axial, about 60% are associated with vasogenic cerebral edema. Microcystic meningiomas, in particular, exhibit a high incidence of peritumoral edema. Cystic changes, either extratumoral or intratumoral, are rare in meningiomas with 10 cases in this study. Intratumoral hemorrhages are occasionally observed, with six cases in this study, one associated with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage.[8] While avid and homogenous contrast enhancement is typical, heterogenous or ring enhancement may occur, especially in cases with central cyst formation, hemorrhage, or necrosis [Table 4].

Table 4: Distinguishing features of subtypes of meningioma.

Pathological subtype Distinguishing imaging features Meningothelial Classical meningioma pattern Fibrous T2W hypointensity Transitional T2W heterogeneous appearance Psammomatous Dense calcification Angiomatous Large, prominent intratumoural and peritumoral feeding vessels Microcystic T1W hypointensity Secretory Skull base location, T2W hyperintensity Lymphoplasmacyte-rich En-plaque pattern Clear cell Cerebellopontine angle location, osteolysis Chordoid High mean ADC values Metaplastic Mesenchymal components on background of meningioma Atypical and WHO grade III Ill-defined margins, diffusion restrictionNumerous studies have sought to correlate MRI patterns with the various histopathological subtypes of meningiomas, providing valuable insights into accurate diagnosis and classification.[7,10]

Hoover et al. (2011)[7]: Distinguished soft from firm/fibrous meningiomas based on MRI. Soft meningiomas showed hypointensity on T1 and hyperintensity on T2, while firm/fibrous tumors appeared isointense on T1 and hypointense on T2. This aids surgeons during operations

Hale et al. (2018)[10]: Retrospective study of 128 patients identified predictors of high-grade meningioma through MRI. Predictors included tumor necrosis, increased peritumoral edema, location along the falx or convexity, presence of draining veins, and tumor volume.

Differential diagnosis and mimics for extra-axial tumorsMeningiomas necessitate differentiation from similar extra-axial dural-based conditions, and MRI plays a pivotal role in this diagnostic challenge [Table 5]: [9,11]

Table 5: Differential diagnosis/mimics for extra-axial tumors.

Type Distinguishing features Solitary fibrous tumour T2WI: mixed signal due to hypointense regions of collagen and these hypointense regions enhance. Separate regions of different T2 signal can cause Yin-Yang sign Dural Metastasis T2W –variable, typical rCBV values of less than 2 Schwannoma Do not have a propensity to involve the internal auditory canal (which is a fairly constant feature of schwannomas) Lymphoma may be lobulated with indistinct ‘fluffy borders’ and restriction on DWI . Sarcoidosis Presence of pulmonary sarcoidosis can aid in distinguishing it from meningiomas Glioblastoma High lipid and high lipid-choline ratio on MRS,restriction on DWI. Venous vascular malformation of the dura or venous sinuses Delayed slow centripetal “filling in” of the mass on dynamic contrast-enhanced MR is suggestive of hemangioma. Melanocytic tumour Usually contain areas of T1 hyperintensity due to melanin and haemorrhage.Several neoplastic and non-neoplastic entities can mimic meningiomas both clinically and radiologically. Solitary fibrous tumor, rare WHO grade II neoplasms, differ from meningiomas by lacking calcification and hyperostosis but may cause skull erosion and display heterogeneous enhancement with prominent internal flow voids [Figures 1 and 2]. These tumors often have a narrow or broad dural attachment. Dural metastases, which may present with an enhancing dural tail, typically appear hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI sequences. Common sources include breast carcinoma, adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, and renal cell carcinoma, with multiple lesions often suggesting metastases over meningiomas.

Secondary CNS lymphoma can also mimic meningiomas, presenting as dural-based lesions that are isointense to hypointense on T2-weighted sequences with intense post-contrast enhancement. These lesions may involve the leptomeninges and present as multiple. Vestibular schwannoma is also a close mimicker of CP angle meningiomas; however, vestibular schwannomas have a propensity to involve the internal auditory canal (which is a fairly constant feature of schwannomas) [Figure 7]. Sarcoidosis, affecting the CNS in about 5% of cases, can involve various CNS structures including the dura, leptomeninges, perivascular subarachnoid spaces, cranial nerves, and brain parenchyma. Sarcoid lesions may mimic meningiomas, appearing hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, with homogeneous post-contrast enhancement. The presence of pulmonary sarcoidosis can aid in distinguishing it from meningiomas. Other less important mimics are venous vascular malformation of the dura or venous sinuses, glioblastoma, and melanocytic tumor. The dural tail sign, commonly associated with meningiomas, should be interpreted carefully, as it also appears in other dural conditions.

Export to PPT

CONCLUSIONMeningiomas are the commonest extra-axial tumors of the CNS and can have a varied appearance on imaging. There are a number of typical and atypical MRI features of meningiomas that are described and it is important for the reporting radiologist to have a broad understanding of their variable potential appearances. MRI is the most important preoperative investigation in the diagnosis and grading of meningioma and it also helps to differentiate it from other conditions that mimic meningioma.

留言 (0)