Women’s health is a complex topic. It has been mischaracterized as reproductive health due to a misconceived gender role stereotype, delayed due to sociocultural barriers and economic dependency, and largely ignored due to a ‘non-superior’ and ‘not equal’ position given to women in societies. Today, more women work, more women are financially independent, and more women die of non-obstetric causes than at any point in history1. Yet, women’s health, in most parts of the globe, starts at menarche and ends with menopause. The 2023 Women Deliver Conference serves as a timely reminder that to envision an equitable future, it is crucial to reevaluate our approach to women’s health and look beyond the reproductive bounds of life2. We aim to highlight the challenges in delivering adequate healthcare to women and propose recommendations for the same.

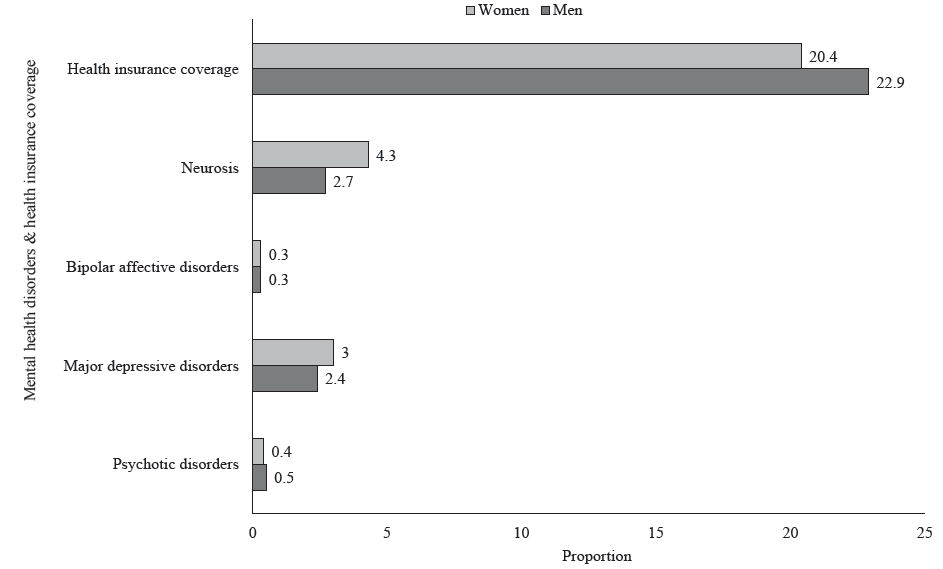

Undeniably, over the last two decades, reproductive health provisions have had a positive effect on reducing maternal mortality and morbidity globally3. Abortion measures in some regions and menstrual and maternity leaves have, to a certain extent, enhanced reproductive autonomy4. However, the issue of women’s rights, at home, in the community, and at workplaces largely remains unaddressed. In some indigenous populations in Asia, women have the right to choose their partners. However, the same women have to stay in dilapidated huts outside the village boundaries during menstruation and childbirth5,6. While a lot has been written on this issue, the focus has always been on menstrual hygiene and taboos7,8. To paint a larger picture of women’s health, mental health effects of this monthly isolation, vulnerability to human-wildlife conflict, malnutrition and loss of work/wages leading to economic dependency must also be taken into consideration9. Unindicated removal of uteri in early-age women (<40 yr) impacts women’s mental, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular health significantly10. Furthermore, forced hysterectomies to cease menstruation and child-bearing, and forced sterilizations to restrict pregnancies in order increase work productivity severely infringe woman’s rights and autonomy11,12. Endometriosis globally affects about 5-15 per cent women of reproductive age13 and has far more physical and mental implications than just being ‘a cause of infertility’. A recent study has estimated the crude incidence rate of cancer cases in India to be 100.4 per 100000, with a greater number of females affected than males14. According to the National Family Health Survey– 4 (NFHS-4) estimates, the prevalence of hypertension (11% vs. 15%) and diabetes mellitus (4.6% vs. 4.8%) is currently lower in women compared to men. However, in terms of multimorbidity in individuals aged 45 yr and above, the proportion of three or more non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has been reported to be significantly higher in women [20%-95% Confidence Interval (CI): 19.6% to 20.4%] than men (95% CI: 15.8% to 16.6%)15. The overall prevalence of reporting at least one NCD (physical or mental) was found to be higher among women as compared to men16. Similarly, the relative risk of fatal ischemic heart disease secondary to diabetes was twice as high in women than men17.

The sex-specific mechanisms, including the role of the placenta in the development of NCDs warrant more attention18. Additionally, sex and gender differences influence the severity of infections as well as drug pharmacology19. However, gender-disaggregated evidence in clinical trials of drugs and devices is largely absent. A study investigating clinical trials on COVID-19 reported that only four per cent of the trials had a statistical plan with sex/gender as an analytical variable, and only about 18 per cent published trials reported sex-disaggregated results19. By recognizing the gender-specific aspects and determinants of disease risk, we can develop more targeted prevention, monitoring, evaluation, and care strategies, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes for women worldwide (Fig. 1).

Export to PPT

This understanding can be furthered by generating credible region-specific data, which in turn requires making resources available in the data-scarce low- and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)20. Gender-based disparities between high-income (HICs) and LMICs compound the challenge. Women constitute about 67 per cent of the global health and social care workforce, yet are paid 24 per cent less than men, with women from LMICs doing maximum unpaid work. In India, women spend around 73 per cent of their total daily working time doing unpaid work, while men spend only 11 per cent21.

A standardised comprehensive definition of women’s health can outline the scope of the problem and help prioritise funding allocation and gender-specific data collection. Additionally, one must acknowledge the interconnected nature of the socio-cultural-economic categorisations and their impact on gender and health inequalities. Advances in breast and cervical cancer screening, vaccinations including COVID-19, and contraception methods promise a positive change, but making them available to the last woman in a remote tribal hamlet in Asia or Africa needs a comprehensive understanding of the determinants of gender inequality and a concerted response that is culture-sensitive. National surveys like the NFHS that form the backbone of population-based data generation in a high-population country like India need to become more gender-inclusive and expand their focus beyond antenatal care and institutional deliveries. In most countries, women have a higher life expectancy than men, accentuating the need for long-term care for chronic illnesses in both public and private sectors. By substituting the disadvantage-causing frameworks with cohesive and inclusive structures, we can address the systemic inequalities and improve the quality of healthcare services22. Developing national and international health policies and programmes that prioritise the needs of the most disadvantaged and underserved have to be the foundation of the roadmap to words achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage23.

Creating awareness about physical and mental health, having various public health programmes catering to various NCDs in women of various age groups, emphasising on importance of health/medical insurances could be seen as some crucial points to be addressed. Education and counselling of women and sensitisation of healthcare providers to gender-specific needs can aid in eliminating the gender bias in healthcare service delivery. Such priming would be impactful to direct gender-sensitive healthcare approaches for individuals undergoing gender reassignment procedures and treatments. Currently, the medical curriculum focuses extensively on the reproductive health of women, and expanding this focus beyond the genitourinary organs can motivate young medical professionals to handle the gender issue more sensitively24. This would require policy and decision-making to include significant representation of stakeholders, namely, women from various socioeconomic and regional backgrounds. Particularly in India, schemes like the Model Rural Health Research Unit (MRHRUs) that envision technology transfer to rural areas have the potential to become the flag-bearers of gender-equitable healthcare and holistic research. Such institutions, with active community engagement, can lead the multi-sector consortiums on women’s health, ensuring that no woman, irrespective of ethnicity or background, is left out.

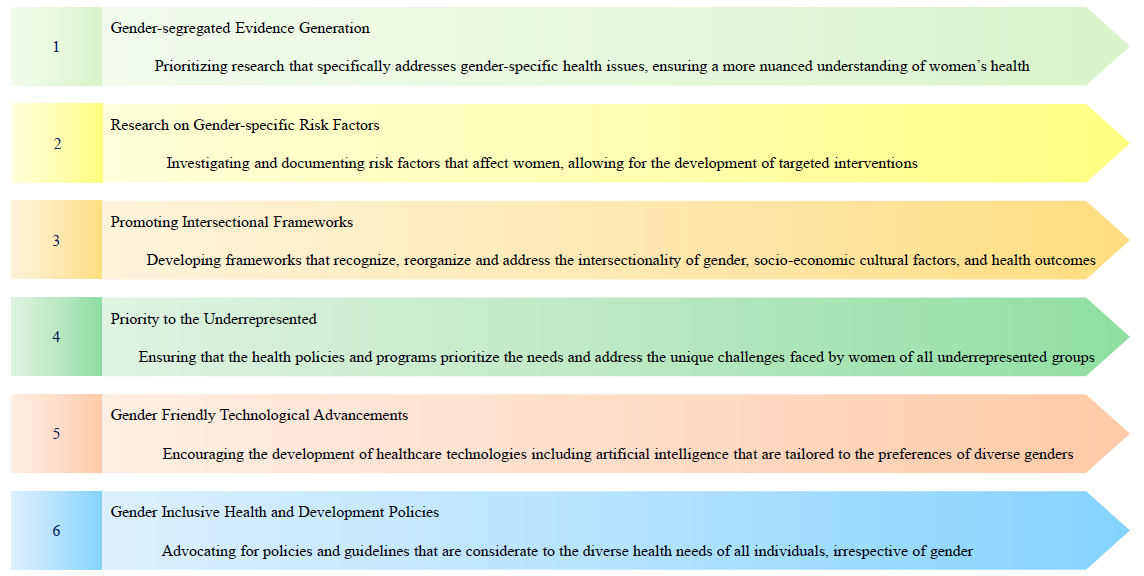

To envision a future where women’s health is addressed comprehensively, the following recommendations (Fig. 2) are proposed: (i) gender-segregated evidence generation which includes prioritizing research that specifically addresses gender-specific health issues, ensuring a more nuanced understanding of women’s health; (ii) research on gender-specific risk factors involving investigation and documenting risk factors that affect women, allowing for the development of targeted interventions; (iii) adopting gender equality and health equity promoting intersectional frameworks: developing frameworks that recognise, reorganise and address the intersectionality of gender, socio-economic-cultural factors, and health outcomes; (iv) priority to the underrepresented: considering the unique challenges faced by women in different communities, ensuring that the health policies and programmes prioritize the needs of all underrepresented groups; (v) gender-friendly technological advancements: encouraging the development of healthcare technologies, including artificial intelligence that are tailored to the preferences of diverse genders; and (vi) gender-inclusive health and development policies: advocating for policies and guidelines that are considerate to the diverse health needs of all individuals, irrespective of gender.

Export to PPT

留言 (0)