Patients with Parkinson's disease (pwPD) or atypical parkinsonism [e.g., multiple system atrophy (MSA), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)] (1, 2) usually complain of impaired balance, reduced postural reflexes, freezing of gait, festination, and difficulty in reacting to an external perturbance (3). It has been estimated that pwPD experience two to three times more falls than healthy older adults (4–7). Such increased risk of falls and associated injuries progressively reduce patients' autonomy from caregivers and affect their quality of life (8).

The assessment of balance in pwPD is usually based on clinical scales (9–13), providing a qualitative evaluation of postural instability. Other dynamic tests have been developed to obtain quantitative information about patients' ability to maintain postural control (13–15). These assessments have been suggested to be more sensitive to advanced stages of PD, while they fail to detect differences in the early stages of the disease (16).

Instrumental posturography represents a valuable technique for assessing and monitoring pwPD, providing centimeter-accurate measurements, and therefore capable of early discriminating different patterns among patients (16). It has been suggested to monitor disease progression and understand the effectiveness of physiotherapeutic, pharmacological therapy, and invasive treatments such as Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) (17–19). The wide availability of instrumentation for stabilometric assessment, with relatively low costs, has encouraged its dissemination in healthcare institutions, leading to increased scientific publications on the topic. A search on Pubmed, including the keywords “Parkinson's disease” and “posturography,” yielded nearly 500 scientific articles published in the past 24 years, with about 40 papers/year in recent years. More than 80% of these papers were published in Journals categorized as clinical, according to Scimago Journal and Country Rank (20). The remaining 20% have been published in engineering or multidisciplinary journals and focused on developing new indicators to be extracted from posturography data to describe patients' conditions. On the one hand, this helps to refine the research for the best outcome measures able to discriminate different patients; on the other hand, newly generated parameters must have a relevant clinical meaning for clinicians to interpret them accurately and integrate them effectively into their daily practice. Among the main limiting factors of instrumental posturography highlighted in the literature there are: the absence of a defined “normal pattern”, the lack of standardization of the protocols, and the large number of parameters that can be computed (21). This heterogeneous array of options in the literature, particularly in the absence of engineering expertise, can lead to uncertainty among physicians who need to select which parameter to use in their daily practice. Transferability to clinical practice should be the ultimate goal of biomedical research, aimed at improving clinicians' knowledge and, consequently, patient management from diagnosis to treatment.

We designed a critical appraisal to evaluate whether the reporting of studies on static posturography in pwPD is sufficiently comprehensive or requires targeted guidance to enhance quality. This approach aligns with similar reviews of other innovative methods, such as gait analysis combined with artificial intelligence (22). While previous works have clearly highlighted the heterogeneity of outcomes used in posturography research (16, 23, 24), none have offered practical guidance to establish a reference framework for improving the reporting of future studies.

This study aims to systematically review the literature on the use of static posturography to assess pwPD and atypical parkinsonism, appraise its clinical and technical aspects, and identify gaps hindering its translation into the clinical routine. The findings will be used to offer valuable recommendations aimed at enhancing external validity and replicability of future studies.

2 MethodsThe current systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guideline (25).

To increase this research's clarity, transparency, and reproducibility, the protocol was a-priori registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 6th February 2024 (ID CRD42024500777).

2.1 Research question and strategiesThe leading question for this investigation was: “How is posturography used in the assessment of static balance in pwPD and atypical parkinsonism?”.

A scientific librarian developed comprehensive and systematic searches. We did not use the PICO framework because neither the Intervention nor the Comparison components could be defined for most studies included in this review, which does not focus on evaluating the effectiveness of a specific intervention on a particular outcome. Therefore, the search strings were developed through an iterative process. The research was conducted in January 2024 within the following databases: Medline, Cinahl, Embase, and Scopus. Furthermore, a manual cross-reference search was performed on the reference lists of included articles. No time limits were set for publications to be included.

The complete search strategies can be consulted in Table 1.

Table 1. Search strategies, according to each database.

2.2 Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria were: (a) studies involving adult pwPD or other types of atypical parkinsonism; (b) studies investigating pwPD using static posturography, with any protocol that included barefoot bipedal upright stance acquired with eyes open on a firm surface, which will be from now on considered the “baseline condition” (along with the baseline condition, protocols could then involve other conditions, e.g., open/closed eyes, feet apart/together, firm/foam surface, cognitive tasks); (c) primary peer-reviewed studies (e.g., RCT, clinical study, observational study); (d) full text available in English.

The exclusion criteria were: (a) studies including only healthy individuals or patients with other pathologies; (b) studies not involving humans (i.e., modeling studies); (c) acquisition protocol based on dynamic posturography only (e.g., Sensory Organization Test, Functional Reach Test); (d) sessions acquired while wearing goggles or similar headsets; (e) studies in which patients were provided onscreen feedback of the position of their center of pressure to stabilize during the assessment; (f) patients holding their arms away from the body so that the center of pressure is shifted (e.g., Romberg position).

We were interested in all outcome measures derived from static posturography acquired in the baseline condition.

2.3 Study selectionAfter all databases were searched, reports were exported to EndNote20 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA), and duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were imported to Rayyan (26) online software. Two independent reviewers (LC and MCB) blindly screened their title, abstract, and full text. Discrepancies were discussed in a consensus meeting. If agreement could not be reached, a third researcher was called upon to solve any discrepancy (AM).

2.4 Data extraction and reportTwo reviewers (MCB and LC) independently extracted the data. When the computation methods of the parameters were unclear, a third author (AM), a bioengineer with 20 years of experience in instrumental motion and posture analysis, was consulted. When necessary, the authors were contacted by email to obtain missing data from the reports, and information was added if they replied in 1 month.

The following information was summarized in a custom table: first author, year of publication, journal, aims of the study, sample size, patients' demographic and clinical characteristics, any treatment undergone by patients, protocol adopted for the posturographic assessment (including different conditions tested, number and duration of repetitions, and dosage of any drugs or brain stimulation), task conditions (including foot positioning, gaze fixation, and arm positions), technical details of the instrumentations and data processing (e.g., filters applied), any posturographic parameter derived from baseline posture. Parameters (means and standard deviations, median, or ranges) were retrieved from text, tables, or obtained from figures when necessary. Findings were also presented in a narrative synthesis, grouped by the five domains illustrated in the following paragraph.

2.5 Quality assessmentThe three reviewers involved in the previous steps critically appraised the included studies. In case of doubts about the clinical characteristics of the sample, a neurologist with extensive expertise in pwPD was consulted.

To standardize the quality assessment procedure, a tailored set of quality questions was designed, tested on a random sample of 30 studies, and refined progressively until its final version, reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Tailored critical appraisal for the assessment of the included studies, addressing five domains that should always be described.

The questions, listed according to the traditional structure of the paper, explore five domains:

1) Study methodology (Q1, Q3, Q5, Q6, Q17, Q18), including study design, research question, homogeneity or stratification according to disease severity, sample size or power analysis computation, and statistical analysis;

2) Clinical aspects (Q4, Q7), including the description of the sample, and description of the intervention—if any;

3) Assessment protocol (Q9, Q10, Q11), including information about balance assessment procedures and their replicability;

4) Technical aspects (Q8, Q14, Q15, Q16), including computational operations and engineering data management;

5) Transferability to clinical practice (Q2, Q12, Q13, Q19), including the paper's added value to the literature to improve clinical management of pwPD.

Each question was scored on a three-level basis: 1 for yes, 0.5 for limited details, and 0 for no. For some items, the score Not Applicable (NA) was added. The total score was calculated for each study to evaluate its overall quality. The total score of each question—and, consequently, of each category—was then expressed as a percentage of the maximum achievable score (i.e., considering only the assessable studies), not to penalize studies that received an NA score for some items.

Finally, studies were categorized into three groups: high-quality (total score exceeding 80%), medium-quality (total score ranging between 51 and 79%), and low-quality (total score below 50%) as in Samadi Kohnehshahri et al. (22). We also separately evaluated the quality of each category, determined by the ratio of question scores at each level (low, medium, high) and the total number of questions linked to that category.

2.6 Differences in critical appraisal scores due to the journal subject areaWe also investigated whether studies published in strictly clinical or mixed (i.e., clinical and bioengineering, bioengineering only, neurophysiology) journals received different scores in the categories of critical appraisal. We labeled the journal as clinical or mixed based on the main “subject area and category” on the Scimago Journal and Country Rank portal (20). When journals were not indexed on Scimago or classified as “multidisciplinary” (e.g., PlosOne), classification was carried out by examining the journal's aims, the study itself, and the authors' affiliations. Critical appraisal analysis was then performed for these two subgroups.

3 ResultsThe original search identified 1,893 articles, which were turned into 859 after removing duplicates. These were screened for title and abstract according to the eligibility criteria. In this phase, the main reasons for exclusion were wrong outcomes or protocols employed (e.g., not involving the baseline condition, having patients performing dynamic balance tests) and wrong publication type (e.g., conference abstracts). Twenty-two studies required a third reviewer's intervention, and nine were included after consultation, leading to 130 eligible papers. In addition, two out of ten studies identified by hand searching were included, for a total of 132 studies included in the review (see the PRISMA Flowchart in Figure 1) (17–19, 27–155).

Figure 1. Prisma flowchart of the literature search on instrumental static balance assessment for patients with Parkinson's disease and atypical parkinsonism.

3.1 Data extractionThe comprehensive table containing all information extracted from the included studies can be found in Supplementary material 1.

Of the 132 studies, 115 focused on pwPD and 17 on atypical parkinsonism (MSA, PSP). Ninety-five were observational studies, and 37 were interventional studies. The former were generally cross-sectional studies aimed at describing the features of balance management of the included sample. The latter mainly evaluated a drug's or treatment's effectiveness on patients' postural ability.

Overall, 4,262 patients, aged 43–91, were assessed with static posturography in baseline condition.

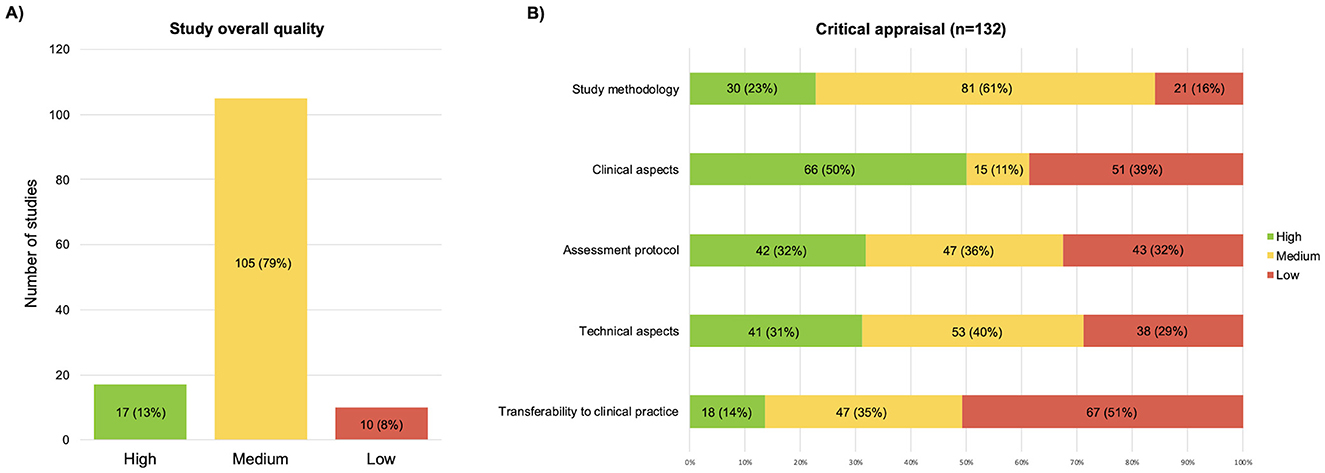

3.2 Quality assessmentThe results obtained from the scores of each quality question are reported in Supplementary material 2. Of the 132 studies, 17 (13%) were rated high-quality, 105 (79%) medium-quality, and 10 (8%) low-quality (Figure 2A). The category “clinical aspects” received high-quality scores in half of the studies (see Figure 2B). The “technical aspects” and “study methodology” categories received mostly medium-quality ratings. Finally, the two categories with the lowest scores were “transferability to clinical practice” and “assessment protocol”.

Figure 2. Graphic representation of the results of the critical appraisal, (A) overall scores; (B) scores split by the five domains of the critical appraisal.

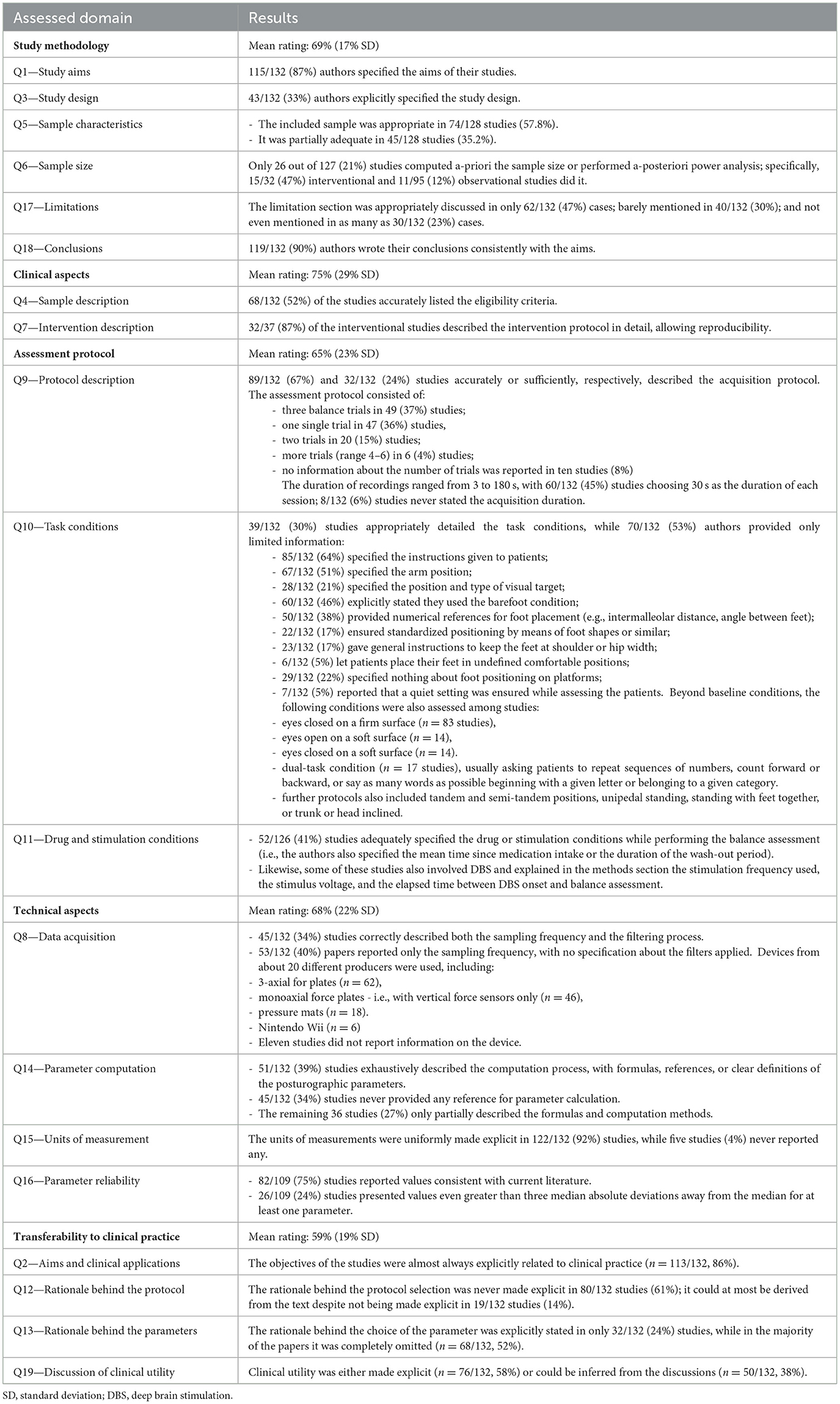

Table 3 shows the results of each item from the five domains, detailing the average rating scores (see Supplementary material 2 for details of individual studies). The total score of each question was calculated as a percentage, excluding studies assessed as “NA” to avoid penalizing those questions. Consequently, some ratios have denominators lower than the total number of included studies (e.g., 74/128).

Table 3. Results of the critical appraisal for each item.

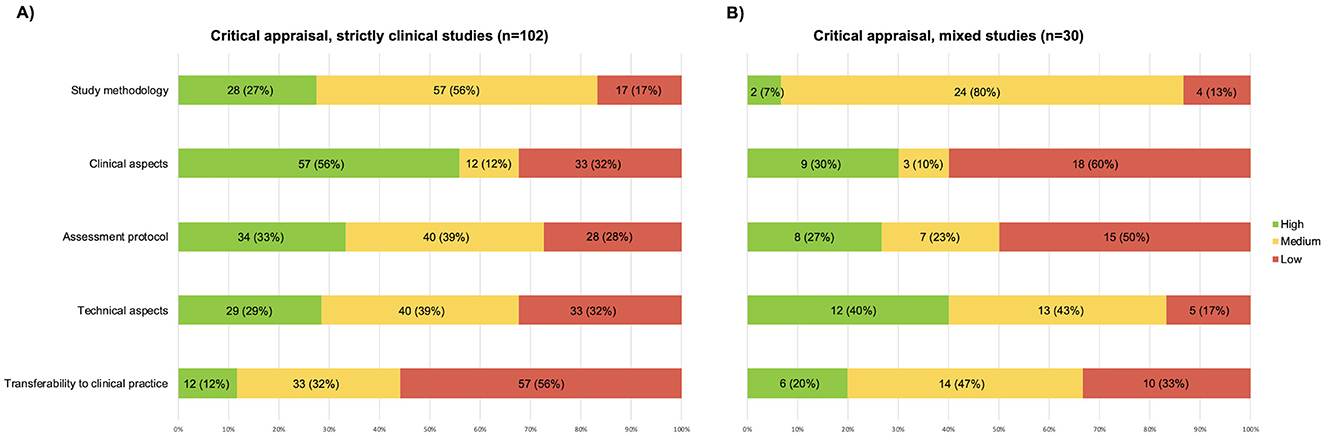

3.3 Differences in critical appraisal scores due to the journal subject areaOf the included studies, 102/132 were strictly clinical, and 30/132 were mixed studies.

Of the 102 clinical studies, 13 (13%), were rated high-quality, 81 (79%) medium-quality, and 8 (8%) low-quality. Of the 30 mixed studies, 4 (13%) were rated high-quality, 24 (80%) medium-quality, and 2 (7%) low-quality.

Regarding clinical studies, the domains with the highest scores were “clinical aspects” and “assessment protocol” (see Figure 3A). The categories with the lowest scores were “transferability to clinical practice” and “technical aspects”. Thirteen clinical studies were cumulatively classified as high-quality. Only one study received high-quality ratings for all five domains (35).

Figure 3. Graphic representation of the results of the critical appraisal, (A) papers published in clinical journals; (B) papers published in mixed journals.

Regarding mixed studies, the domain with the highest score was “technical aspects” (see Figure 3B). The categories with the lowest scores were “clinical aspects” and “assessment protocol”. Four mixed studies received high-quality global evaluation but no study received high-quality ratings for all five domains.

It is also worth mentioning that more than half of the studies received medium-quality scores for the domain “study methodology”.

4 DiscussionWe conducted this systematic review to assess the use of static posturography in pwPD, analyzing which types of information are more detailed and how they may impact clinical transferability.

Based on the appraisal conducted, most of the included studies were rated as medium-quality, and only 17 studies were considered of high-quality (17, 32, 34–36, 47, 57, 63, 70, 112, 115, 117, 125, 126, 147, 148, 150).

The “”transferability to clinical practice” was the lowest-scoring domain at the critical appraisal, with only 14% of high-quality studies. From the results reported in Figure 2B and Table 3, this finding is attributable to three main factors. These are (1) The lack of discussion on the rationale adopted for choosing the posturographic protocol and computing the parameters used; (2) The conduction of the studies on limited, very heterogeneous, or insufficiently characterized samples from a clinical point of view; and (3) The lack of transparent reporting on the procedures for conducting the assessment and computing the parameters analyzed.

The interplay of these factors, identified through the critical appraisal items, prevented us from taking the next step in this review: summarizing the results as mean baseline values for pwPD at different stages of the pathology (e.g., H&Y score) or assessing the average variation in posturographic parameters following an intervention. A selection of studies with the highest appraisal scores was indicated above. The following paragraphs analyze these three points in the included studies, their impact on clinical transferability, and suggest possible solutions.

4.1 The rationale supporting the posturographic assessment of pwPD in the literatureDespite being rarely mentioned as a key point among the studies, three main clinical uses of the posturographic assessment in pwPD emerge from this review. These are: (1) to evaluate the effectiveness of rehabilitation treatments (37 clinical trials), (2) to monitor the course of the disease, and (3) to distinguish subgroups of patients (95 observational studies).

Only 16 studies have explicitly discussed how the assessment protocol and investigated posturographic parameters can be used in clinical routine (34–36, 38, 39, 42, 43, 50, 63, 72, 110, 115, 138, 147, 148, 150). Surprisingly, the lack of explanation of a clear rationale is particularly notable in studies published in purely clinical journals (see Figure 3A), which, on the contrary, are expected to be more accurate about this. This makes it difficult for readers to translate the literature into their daily clinical practice.

The reasons for this flaw may be manifold. It is possible that the authors took the rationale behind their choices for granted, as they are used to using these tools and dealing with these parameters every day. Also, the authors might have focused on the research-related aspects of their studies, so they did not discuss the clinical rationale and relevance of both their protocol and results. Next, several journals did not require to address this point explicitly. Concerning the choice of the posturographic parameters used in the studies included in this review, their selection may be due to—and limited by—the software of the commercial device used in the study. These, in fact, typically provide only the most used and standard outcomes, such as COP velocity and area, which may not be the most informative ones when assessing pwPD.

It is known that it takes about two decades to implement evidence into clinical practice (156). To bridge this time gap, the literature must focus on clinical relevance and transferability of findings. Many scientific journals require a short paragraph on clinical implications when submitting a manuscript. In line with this, future studies should discuss which additional information the posturographic test provides other than the clinical assessment, why it is essential to perform it in pwPD, and the possible contribution of the assessing protocol (task and parameters) to differential diagnosis or early recognition of symptoms or treatment effect assessment or patient status monitoring.

4.2 Characteristics of pwPD assessed by posturography in the literatureThis systematic review included both pwPD and patients with atypical parkinsonism. To our knowledge, this is new in the literature, as this is the only review that included both populations. Despite being rarer, diseases such as PSP and MSA manifest clinical symptoms at onset that can be confused with PD and, therefore, deserve to be investigated as well and differentiated.

4.2.1 The choice and description of the sampleA limited number of studies reported all the details about the sample, which is necessary to ensure the external validity of the results. Accurately describing sample characteristics allows readers to decide whether or not to compare with their reference patients. Clinical aspects were better described by the studies published in clinical journals (56% of high-quality studies), while the rate dropped to 30% for papers published in mixed journals. This is likely due to a greater sensitivity of clinical teams in reporting aspects that characterize the sample, compared to engineering groups.

Only 68/132 (52%) studies fully and accurately described the sample (see Q4). For pwPD, many studies reported diagnostic criteria and characterized patients through the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) (157) and the Hoehn and Yahr staging (H&Y) (158) scales, as well as additional functional tests. For patients with atypical parkinsonism, a variety of specific scales can be used, depending on the disease, including the Unified Multiple System Atrophy Rating Scale, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale, and Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (159–161). In progressive diseases such as PD, it might be relevant to report the time from the onset of the first symptoms or diagnosis, as well as the age and gender of the sample. In our review, the sample was considered “adequate” when it included patients with homogeneous characteristics in the case of intervention/descriptive studies and patients with heterogeneous characteristics in the case of correlation studies (see Q5). Among the included studies, 58% set the inclusion criteria consistently with the aim of the study. The adequacy of the sample allows the authors to identify specific findings for a homogeneous subgroup in terms of disease severity, supporting the translation of the results into clinical practice. Finally, the authors should specify whether the study was conducted solely for research purposes or if posturography acquisition was integrated as standard clinical practice.

When conducting a clinical study, the intervention should also be described. In our review, 86.5% of the studies detailed their protocols, including the type of intervention, frequency, and dosage, thus allowing reproducibility (see Q7). The TIDieR checklist was specifically developed in 2014 to improve the reporting quality for healthcare interventions and may further support authors during the writing of their Section 2 (162).

4.2.2 The methodology usedThe methodology domain has contributed to lowering the overall quality of the studies. The number of high-quality studies, already quite low when considering all studies (23%), drops to 7% when considering only studies published in mixed journals.

The main methodological limitation found in the included studies is the rare a-priori sample size calculation (see Q6). Only 24/127 (21%) of the studies calculated the sample size a-priori, along with two other studies (2%) that calculated statistical power a-posteriori. Focusing on interventional studies only, surprisingly, only half (47%) of them were conducted on a sample with an adequately calculated sample size. This is a relevant flaw because it can result in the absence of a statistically significant difference in the posturographic outcomes between the experimental and the control group in the presence of an actual difference (type-II error). The lack of this calculation limits the generalizability of their results and, again, their clinical transferability. Furthermore, it hinders the observation of potential differences between groups (in both observational and clinical studies), thereby impacting clinical decision-making (163).

When considering methodology, it is also appropriate to clarify the weaknesses of a study, which helps naïve readers not to overestimate the results and be aware of the limitations they might encounter if they intend to replicate the work in their daily activities. Only 62/132 studies comprehensively reported the limitations of their work (see Q17), and authors rarely referred to guidelines used during writing. Several reporting guidelines have been published since the late 1990s (e.g., CONSORT for experimental studies–1996) (164) and STROBE for observational studies in 2007 (165). More and more scientific journals require them to be completed during submission, proving that they are a handy tool for ensuring that the required methodological rigor has been met and that all the necessary information has been reported.

4.3 Issues in the reporting of protocol details and technical information in the literatureTwo domains with similar percentages of high-quality studies are “assessment protocol” (32%) and “technical aspects” (31%). Many studies obtained fair scores at the critical appraisal as they correctly provided the necessary information. However, several technical and assessment-related aspects still deserve consideration.

4.3.1 Assessment protocolStudies that include posturographic examination should thoroughly describe how it is performed, and which protocol is adopted so as to allow replicability both in subsequent studies and in clinical practice. Key information to be reported is the number of sessions, their duration, the positioning of the feet and arms, the visual target provided, and the instructions given to the patient before the test.

4.3.1.1 Number and duration of repetitionsIn the current review, almost the same number of studies performed one or three repetitions, with durations ranging from 3 s to 3 min. Such short durations must never be included, as they are dramatically shorter than even the 5–10 s of recording recommended in some studies before collecting data for analysis (166, 167) and, therefore, provide no helpful information on COP characteristics. In the specific case (46) the authors reported the static balance assessment preliminary to gait analysis acquisitions.

The importance of averaging the parameters obtained in at least three successive trials to obtain values close to the subject's actual value is highlighted in the literature (168, 169). As the number of trials increases, the average value of the most commonly used posturographic parameters, such as COP area and velocity, stabilizes. At least 3–4 trials are necessary to stabilize posturographic parameters (167–170). In addition, the availability of multiple trials makes it possible to observe the variability of posturographic parameters between trials and provide further insight into the patient's condition.

The duration of the single test also affects the value of posturographic parameters. The literature has long investigated the best methods of standardizing the examination (166, 171–175), indicating durations between 30 and 90 s. Most (98/132, 74%) of the studies included in this review involved acquisitions with durations between 30 s (60/132, 45%) and 60 s (26/132, 20%).

The duration of 51.2 s—or multiples—observed in several studies (42, 53, 75, 101, 113, 129, 130, 146, 176) may seem strange to the reader and deserves a brief comment. This duration, adequate if not strenuous for the patient, does not derive from a physiological rationale. It depends on the technical characteristics of specific devices available in the 1980s and used for the definition of the first normative data through the work of the group of Gagey and Bizzo (172, 177). The availability of normative values encouraged, at first, the adoption of this duration in subsequent literature and by device manufacturers.

Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that for individuals such as pwPD, excessive duration could induce high levels of fatigue (178). Performing very long trials should be a conscious choice by researchers, possibly justified as done by Workman and colleagues (148). Therefore, evaluations for clinical uses must be based on a trade-off between several factors: the assessment duration, patient fatigue, and the need to obtain multiple trials to compare and mediate. It seems advisable to record 3–4 trials of 30–60s each.

4.3.1.2 Task instructionsTask instructions are another critical factor for the clinical transferability of posturographic assessment. Of the included studies, only 39/132 (30%) specified the conditions under which the patients performed the balance tests, such as the directions given to the patients, the position of the arms and feet, and the visual target.

Instructions given to patients (e.g., “stand as still as possible” and “maintain a comfortable posture”) affect the reactions and the focus they will maintain during the test and, therefore, should be made explicit (179, 180). Similarly, the position of the arms (e.g., along the body, crossed) and the visual aim provided (e.g., “look straight ahead”, “look at a specific point at eye level”) could result in changes in the positioning and sway of the center of pressure (175). If possible, it would also be appropriate to specify that a quiet setting has been ensured throughout the performance of the test, mainly to avoid acoustic spatial orientation (166, 175), as done by some authors (65, 111–113, 116, 120, 148).

Unambiguous clarification of foot positioning is also essential (181). It is not sufficient to ask the patient to position themselves with their feet shoulder-width apart comfortably, nor to ask them to keep them open at shoulder or hip width (28/132 studies). This clearly does not allow for reproducibility. Other 18/132 studies let the patients position themselves at will but ensured position repeatability between trials by marking the initial position acquired. This is certainly a strength for internal validity, but it does not allow comparison of them with external literature and, again, limits the transferability of findings. Therefore, proper reporting of foot placement should always include numerical values for the distance between the feet and the angular opening between them. The literature suggests a distance of 3–5 cm at an angle of 30° (182) for patients with pathologies such that testing with feet together is not feasible and safe. Although it may seem obvious, researchers should always clarify whether the patient wears footwear or is barefoot during testing (only 60/132, 46%, studies among those included explicitly stated this), as the increased surface area—and sometimes, a slight ankle restraint provided by the footwear—, could affect the subject's stability (166).

The current review focused on the fair reporting of posturographic assessment under “baseline” conditions (i.e., eyes open, on a stable surface). Still, the same rigor must be maintained for any further testing. Specific tasks may reveal the patient's hidden postural issues, depending on individual strategies, as the dual-task condition (183). In this case, it is necessary to describe the required task (e.g., “count backward by three units starting from 100”, “list all the names you can think of referable to the animal category”) (18, 54, 67, 101, 103, 121, 140, 150, 153), without merely mentioning a generic cognitive task. Tasks of increasing difficulty require additional attention and may alter simultaneous balance control (184). Again, in the case of tests on unstable surfaces, the material (e.g., foam, gel), thickness (50, 82, 119, 121), and gel viscosity should be described (36, 118), as they change the multiple biomechanical variables in the foot, resulting in an alteration to the distribution of plantar pressures (185).

Finally, since these pwPD are almost always under a drug regimen, it is relevant to clarify the phase (ON/OFF) in which the examination is performed: it is not sufficient to state whether the patient was in the ON or OFF phase. If in OFF, the patient must have performed a wash-out of at least 12 h; if in ON, the peak of maximum action occurs about 1–2 h after the last intake (186). Only 52/126 (41%) studies included in the current review described it correctly. As with the rehabilitative intervention, it is equally important to specify the frequency, voltage of stimulus administration, and timing of stimulation.

4.3.2 Technical aspectsIn addition to information about the protocol, details on data analysis should always be reported in the manuscripts because of their impact on the results and to allow study reproducibility.

In particular, mean value removal, data filtering procedures, calculation of the parameters, and subsequent synthesis methods (e.g., calculation of the mean or median among the many trials, exclusion of the first and last seconds of each trial) should be reported. Using filters and techniques that deviate from traditional practice should be justified, as did Schmit et al. (132), who chose not to apply filters because they intended to characterize dynamic COP patterns in PD.

Studies published in mixed journals, i.e., engineering-contributing journals, better addressed technical aspects (40% high-quality studies vs. 28% high-quality studies published in clinical journals), probably reflecting a greater focus of bioengineering authors on this information. Overall, we observed a lack of standardization in data acquisition, filtering methods, and variable computation, when reported. Low pass filtering frequency, for example, was rarely reported despite its relevant effect on the computed parameters (see Supplementary material 1). This prevents meaningful comparisons between studies and hinders the possibility of synthesizing results.

4.3.2.1 Instrumental set-up1D- and 3D force plates were the most used devices in the studies included in this review. From a technical point of view, 1D force plates with three vertical load cells placed in the shape of an equilateral triangle or four vertical load cells placed in the shape of a rectangle are suited to obtain COP. 3D force plates, which are more expensive, were reasonably available in the centers and used for additional applications, such as gait analysis. Furthermore, despite the adequate technical characteristics of the Nintendo Wii (1D force plate), this device is not certified as a medical device. It cannot be used with patients for clinical assessments. Recent literature is investigating wearable sensors as low-cost tools capable of providing data on patients' balance that is easier to obtain (187). Under quasi-static conditions, the center-of-mass acceleration (measured by inertial sensors) is related to that of CoP (measured by force platforms) (188) and may serve as a cost-effective alternative to force platforms in specific contexts after validation specific to each pathology and impairment level.

Only forty-five out of 132 (34%) authors accurately reported the sampling frequencies and filters applied to the raw data, demonstrating knowledge of their impact on the data. PwPDs usually exhibit a tremor oscillating between 4 and 6 Hz (189). Hence, the sampling frequency must be high enough to observe information regarding COP oscillations.

4.3.2.2 Computation of the posturographic parametersOf the included studies, 51/132 (39%) correctly described the computed parameters using mathematical formulas, precise definitions, or citing other articles. Some terms are often used arbitrarily in the literature, which can lead to confusion and misinterpretation, with the high risk for the inexperienced reader of comparing parameters with the same name that hide different underlying calculations. The most striking example is that of the term “sway area/path area/total area,” used in as many as 20 studies without referring to any formula and therefore with potentially very different meanings (30, 40, 41, 45, 76, 78, 93, 97, 99, 103, 107, 111, 112, 130, 137, 144, 146, 151, 154, 176).

The urgency to create an unambiguous taxonomy emerges from this heterogeneous scenario. The historical reference to which most of the literature refers is Prieto et al. (190). Quijoux et al. have recently suggested a new classification of parameters into four categories, including positional (e.g., COP mean position), dynamic (e.g., COP velocity), frequency (e.g., spectral total power), and stochastic (e.g., sample entropy) features (23). Researchers can also rely on open libraries for complete analysis of posturographic data (23). A multidisciplinary approach, including bioengineers in the team, may be adopted to develop specific codes for calculating parameters that are useful to the clinician or to use the available open-source libraries. Moreover, a consensus conference with clinical and engineering experts may establish the best pwPD-specific parameters, providing helpful guidance for software development companies. Alongside the development of new parameters and the informed choice of them, research should be directed toward identifying their psychometric properties and threshold values, capable of distinguishing clinically significant changes, as has been done for spatiotemporal gait parameters for pwPD (191) or some posturographic parameters in healthy subjects (168, 170).

In the current review, five studies (19, 39, 60, 64, 176) never reported the units of measurement of posturographic parameters, and other five studies (18, 43, 55, 57, 155) only partially reported them. As many as 26/109 (24%) studies reported values much higher (>3 MAD) than those found in the literature. In some cases, this could be due to typos in the reported unit of measurement, but this confirms the need to promote clear standards and guidelines in the performance, analysis, and reporting of posturographic data.

To compare the posturographic data obtained during daily clinical practice with those published in the literature, it is mandatory that the clinical characteristics of the samples are comparable and that the acquisition protocol and technical handling of the data are identical. Studies that have accurately reported the necessary information and presented reliable data for comparison are: (17, 35, 115, 130) for pwPD with H&Y ≤ 2, (17, 101, 112, 115, 125, 130, 131) for pwPD with H&Y > 2, and (112) for atypical parkinsonism.

4.4 LimitationsThis review has some limitations that need to be considered.

First, we included studies that reported balance assessment under the “baseline” condition. So, other protocols (e.g., dynamic posturography), which could provide additional relevant information and valuable hints for clinical practice, were not considered.

The search was conducted on four databases and by hand searching the references, but some relevant papers not indexed through the keywords entered in the search strings may have been missed.

Finally, the appraisal we used to assess the included studies on posturography in pwPD is new to the literature and is not a validated tool, as it was constructed ad hoc by the authors. Although we relied on similar examples to conceive the items (16, 23, 24) and develop the scoring system (22), followed an iterative process, and consulted with experts for its design, it is possible that some important aspects were not considered.

5 ConclusionThis systematic review assessed the use of static posturography for quantifying static balance in pwPD and atypical parkinsonism, focusing on the aspects that may hinder the transferability of research results to clinical practice. The main issues identified include a lack of rationale behind posturographic protocols and parameters and unclear sample inclusions. We highlighted several opportunities for enhancing the quality of studies on static posturography in assessing pwPD and atypical parkinsonism. In future studies, authors should: (1) discuss the rationale behind the choice of a specific assessment protocol and a posturographic parameter, (2) detail the inclusion criteria and select appropriate samples according to the aim of the study, and (3) report all the technical information necessary to replicate the procedures and computations. Addressing these areas can significantly improve scientific literature's external validity and clinical transferability to daily practice. This review provided valuable references for each of the five domains considered, supporting the rapid portability of findings to clinical settings.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributionsAM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MBò: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FC: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MBa: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BD: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. VF: Writing – review & editing. GD: Writing – review & editing. GP: Writing – review & editing. FV: Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing. IC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was entirely funded by the Azienda USL-IRCCS of Reggio Emilia.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1528191/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary 1 | Characteristics of the included studies, instructions given to the patients for the static balance test, and posturographic parameters computed in each study.

Supplementary 2 | Results of the critical appraisal for each item and each of the included studies.

References4. Bloem BR, Hausdorff JM, Visser JE, Giladi N. Falls and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a review of two interconnected, episodic phenomena. Mov Disord. (2004) 19:871–84. doi: 10.1002/mds.20115

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Paul SS, Sherrington C, Canning CG, Fung VSC, Close JCT, Lord SR. The relative contribution of physical and cognitive fall risk factors in people with Parkinson's disease: a large prospective cohort study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2014) 28:282–90. doi: 10.1177/1545968313508470

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Pickering RM, Grimbergen YAM, Rigney U, Ashburn A, Mazibrada G, Wood B, et al. Meta-analysis of six prospective studies of falling in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2007) 22:1892–900. doi: 10.1002/mds.21598

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Michałowska M, Fiszer U, Krygowska-Wajs A, Owczarek K. Falls in Parkinson's disease. causes and impact on patients' quality of life. Funct Neurol. (2005) 20:163–8.

9. Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement disorder society-sponsored revision of the unified Parkinson's disease rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. (2008) 23:2129–70. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Ramaker C, Marinus J, Stiggelbout AM, van Hilten BJ. Systematic evaluation of rating scales for impairment and disability in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2002) 17:867–76. doi: 10.1002/mds.10248

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Qutubuddin AA, Pegg PO, Cifu DX, Brown R, McNamee S, Carne W. Validating the Berg Balance Scale for patients with Parkinson's disease: a key to rehabilitation evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2005) 86:789–92. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.005

留言 (0)