There is an increased prevalence of psychosocial comorbidity among individuals with dizziness compared to the general population (1, 2). Staab and Ruckenstein (3) described three relationships between dizziness and psychiatric disorders over the course of illness: a primary psychiatric condition causing dizziness, a primary neurotologic condition that triggers a secondary psychiatric disorder, or a primary neurotologic condition that exacerbates a pre-existing psychiatric disorder. In cross-sectional studies, researchers have found that psychosocial factors in persons with dizziness are associated with poorer quality of life, greater dizziness severity, and dizziness-related disability, as well as greater healthcare utilization (2, 4). These findings have been confirmed in prospective analyses where factors such as anxiety, depression, fear avoidance, and illness perceptions were associated with dizziness-related disability and longer recovery times in persons with dizziness (5–8).

Given the impact of psychosocial factors on measures of disability and prognosis in people experiencing dizziness, it is important to incorporate these factors into treatment plans for vestibular rehabilitation. A number of patient-reported outcomes have been used in this population to screen for anxiety and depressive symptoms such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7, among others (9–13). Scales have also been developed to measure additional psychosocial constructs that impact disability in people with dizziness such as fear avoidance beliefs, catastrophization, and illness beliefs (14–16). Although each of these psychosocial factors have been studied and found to be associated with dizziness-related disability in individuals with dizziness, it remains unclear if certain factors play a more critical role in recovery from a vestibular disorder than others and how to best address them in vestibular rehabilitation clinics. Therefore, there is a need to identify which measures may be most beneficial for clinicians to use to assist with treatment plans and determination of prognosis.

While a number of studies have found associations between psychosocial factors and dizziness-related handicap (4, 17, 18), there is a gap in knowledge regarding the association between psychosocial factors and community mobility in persons with dizziness. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the association between psychosocial factors with future community mobility, activity, and participation among persons with dizziness. A secondary aim was to assess the dimensionality of various measures of psychosocial factors that are used in vestibular rehabilitation.

Materials and methods ParticipantsWe recruited a convenience sample of individuals seeking care for dizziness at a tertiary care balance disorders clinic. The inclusion criteria were that individuals were currently experiencing dizziness, 18 years of age or older, English-speaking, and cognitively able to provide written and verbal informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (STUDY20040188). Diagnoses were made by a oto-neurologist and were categorized as follows: peripheral vestibular hypofunction, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), mixed peripheral vestibular hypofunction and BPPV, Meniere’s Disease, vestibular migraine, mixed vestibular migraine and peripheral vestibular hypofunction, persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD), other central vestibular disorders, imbalance or gait disorders, and unspecified dizziness.

Baseline and three-month follow-up assessmentsParticipants completed an in-person baseline assessment at the tertiary care balance disorders clinic, which included a computerized questionnaire of demographic questions, symptom self-reports, and patient-reported outcome measures. Participants were asked if they would like to be contacted via phone or email in 3 months. Based on their selection, they were either contacted via phone to verbally complete the questionnaires or by email to complete the questionnaires using a survey link. A follow-up time of 3 months was selected because the purpose of our study was to assess the effects of baseline psychosocial factors on future community mobility and participation, and 3 months after the onset of dizziness symptoms are generally considered to be in the chronic phase where symptoms from an acute vestibulopathy would either have recovered or persisted to the chronic phase (19).

Outcome measures Community mobility and participationCommunity mobility was assessed using the Life Space Assessment (LSA), which is a measure of how much and how often an individual moves within their environment and also takes into account assistance needed for mobility (20). The LSA is a self-report measure of mobility over the past month and ranges from a total score of 0 indicating that the person did not move outside of their bedroom to 120 indicating that the person frequently moves outside of their town without assistance. The LSA has excellent reliability and is correlated with dizziness-related disability and quality of life in persons with dizziness (21). In this study, the LSA was used as a dependent variable for our multivariate analysis of the association between psychosocial factors and community mobility.

Activity and participation was measured using the Vestibular Activities and Participation Measure (VAP) (22). The VAP was developed based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health and can identify activity limitations and participation restrictions among persons with dizziness (22, 23). The VAP total score ranges from 0, which indicates no activity limitations or participation restrictions to 4, which indicates complete limitations in activity and participation. The VAP has excellent reliability and is correlated with quality of life and dizziness-related disability among individuals with dizziness (22). In this study, the VAP was used as a dependent variable for our multivariate analysis of the association between psychosocial factors and activity and participation.

Psychosocial factorsWe used several patient-reported outcome measures to measure various psychosocial constructs (i.e., anxiety and depression, fear avoidance, and catastrophization). The HADS was used to measure anxiety and depressive symptoms. The HADS was developed as a screening tool for clinically significant anxiety and depression in primary care settings (9). The HADS consists of an anxiety subscale (HADS-A) and depression subscale (HADS-D), which both range from 0 to 21. A score of 8–10 on either subscale is associated with possible clinically significant anxiety or depression and a score of 11 or greater is associated with probable clinically significant anxiety or depression (9). The HADS has been used in samples of individuals with dizziness and has moderate to strong correlations with dizziness-related disability (12, 18).

We also used the Patient Health Questionnaire for Anxiety and Depression (PHQ-4) as a second measure of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The PHQ-4 was developed as an ultra-brief screening tool for anxiety and depressive symptoms and includes two subscales that each range from 0 to 6 with a score of 3 or greater indicating a possible underlying anxiety and depressive disorder (24).

The Vestibular Activities Avoidance Instrument (VAAI) was developed to identify fear avoidance beliefs and avoidance of activity among persons with dizziness (14). The VAAI consists of 9 items and the total score ranges from 0 to 54 with higher scores indicating greater fear avoidance beliefs and behaviors. The VAAI has excellent reliability and moderate to strong associations with measures of disability among individuals with dizziness (7, 25).

The Dizziness Catastrophizing Scale (DCS) was adapted for individuals experiencing dizziness from the Pain Catastrophizing Scale to measure the construct of catastrophization, which is a maladaptive thought process that amplifies negative assessments of symptoms and anticipates worst case scenario outcomes (15). The DCS has excellent reliability and there is evidence for validity in persons with dizziness (15).

CovariatesWe included age, gender, number of medications, and dizziness severity measures using a visual analogue scale (VAS) as covariates. Age was determined by the difference between the participant’s date of birth and baseline visit date. Gender was self-reported (female, male, other). Number of medications was determined upon review of the electronic health record for current medications. Participants rated their dizziness over the last 24 h using a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10 with 10 being the most severe dizziness (26).

Statistical analysesWe used descriptive statistics (proportion, mean, standard deviation) to assess demographic characteristics and baseline and 3-month outcome measure scores. We used simple linear regression to identify the bivariate associations between baseline psychosocial factors and 3-month community mobility and participation measures. We reported R squared values, unstandardized beta coefficients, standard error, and p-values from the simple linear regression models. Variables that were significant (p < 0.05) were entered into two repeated measures ANOVA models to assess their multivariate relationships to changes in LSA and VAP scores from baseline to 3 months. We included the following covariates based on our previous work: age, gender, number of medications, and dizziness severity (7). We assessed for multicollinearity between predictors using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and identified 0.80 as evidence for multicollinearity (27). We reported the F statistic, p value, and partial eta squared effect sizes to determine the strength of associations using the following thresholds suggested by Cohen (28) small effect = 0.01, medium effect = 0.06, large effect = 0.14.

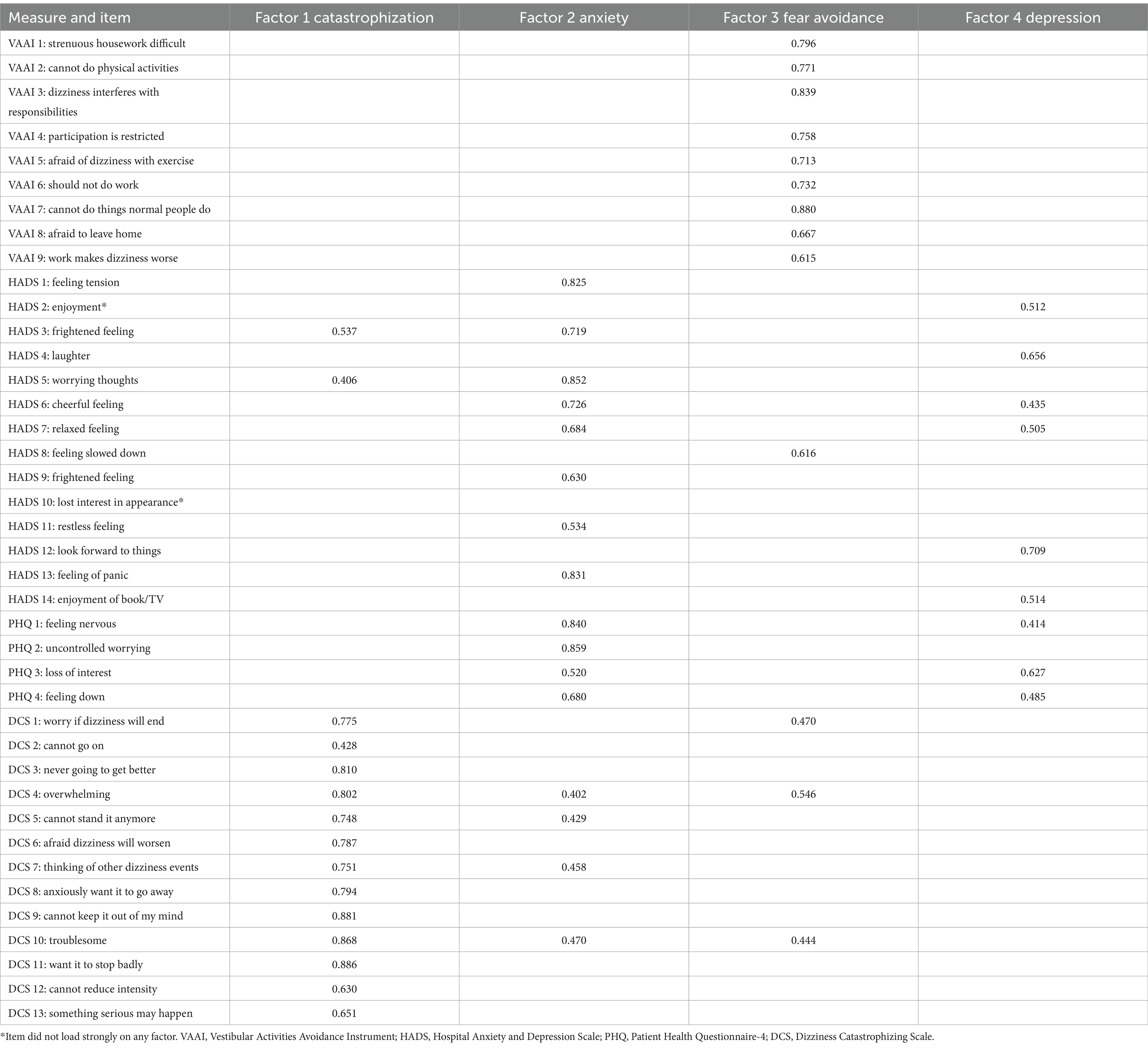

To identify key dimensions of behavioral morbidity contained within psychosocial measures (HADS, PHQ-4, VAAI, and DCS) that may be relevant to patients with dizziness, we performed principal component exploratory factor analysis. First, we evaluated Bartlett’s test of sphericity for significance and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (>0.6) to determine if the items were factorable (29, 30). To determine the number of factors to retain, we evaluated the scree plot for a point of inflection. We then used direct oblimin rotation and reported the factor loadings from the factor structure matrix, which represent simple zero-order correlations of the items, where the size of the loading is not influenced by the correlation between factors (30). We suppressed factor loadings <0.4 to interpret the factors and identify patterns of the item to factor correlations.

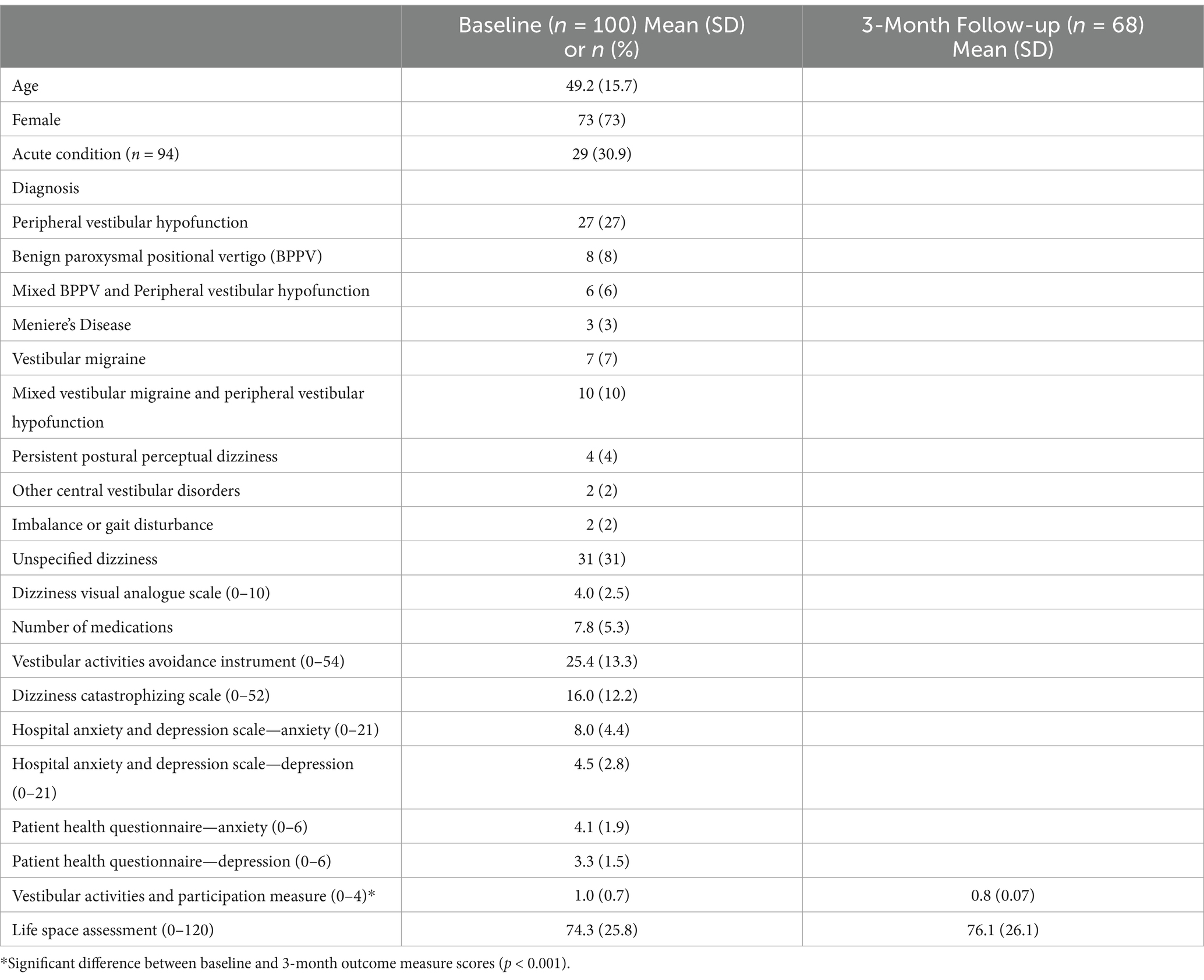

Results Sample descriptionAt baseline, the average age of the sample of 100 participants experiencing dizziness was 49.2 (15.7) years and 73% were female (Table 1). Approximately one-third of the sample were diagnosed with unspecified dizziness (31%), followed by peripheral vestibular hypofunction (27%), mixed vestibular migraine and peripheral vestibular hypofunction (10%), BPPV (8%), and vestibular migraine. Most participants were experiencing chronic symptoms (3 months or greater since symptom onset) with 31% experiencing acute symptoms (n = 6 were missing data for this variable). The average HADS-A was 8.0 (4.4) and the PHQ-4 anxiety subscale was 4.1 (1.9) at baseline, indicating that the study cohort as a whole had possible clinically significant anxiety, but minimal depressive symptoms. The average baseline VAP score was 1.0 (0.7), indicating mild activity limitations and participation restrictions overall, which significantly improved at the 3-month follow-up visit to 0.8 (0.7) (p < 0.001). The average baseline LSA score was 74.3 (25.8), indicating restricted community mobility, which did not improve at the 3-month follow-up visit [76.1 (26.1)].

Table 1. Characteristics and patient-reported outcome measure scores for 100 participants with dizziness.

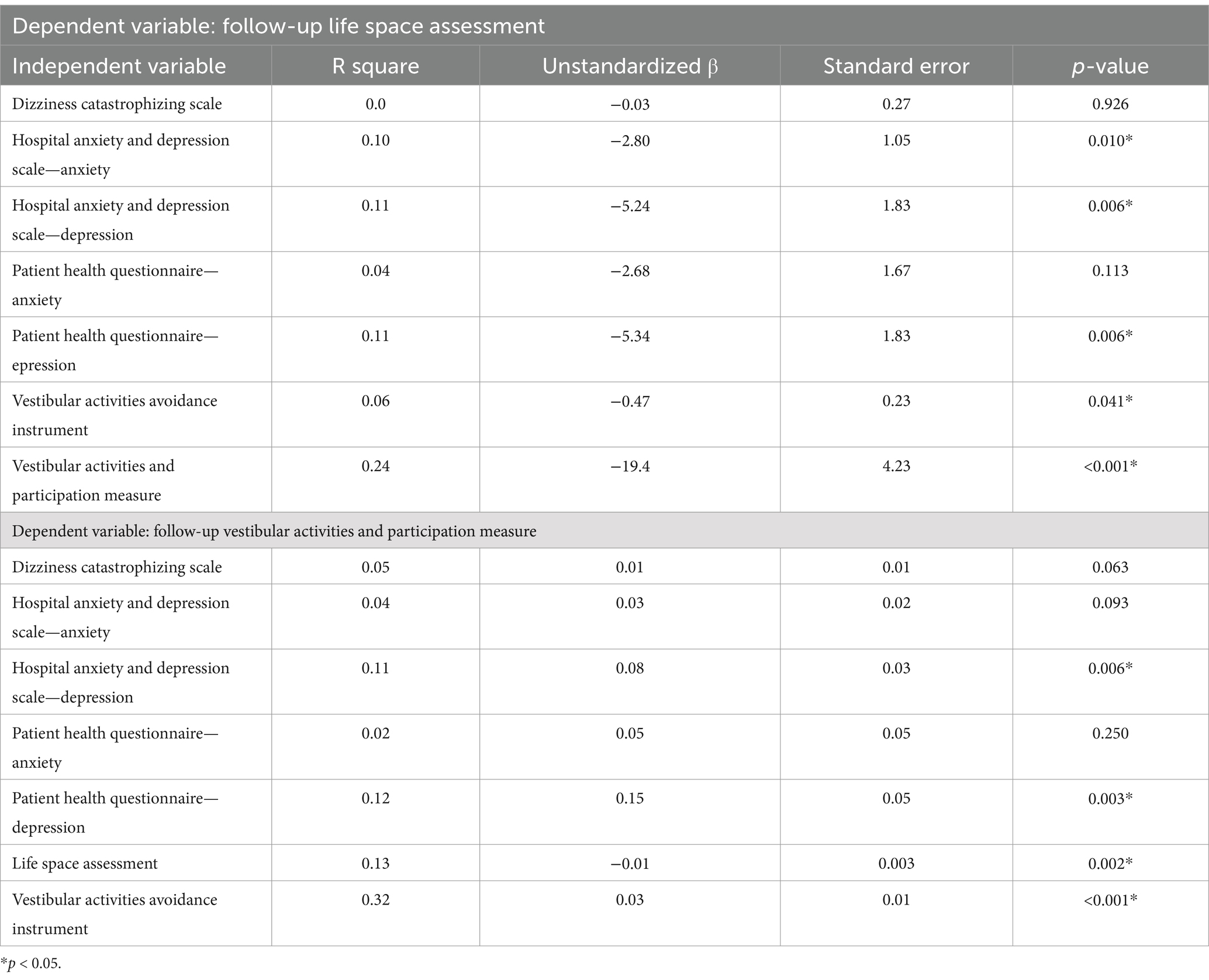

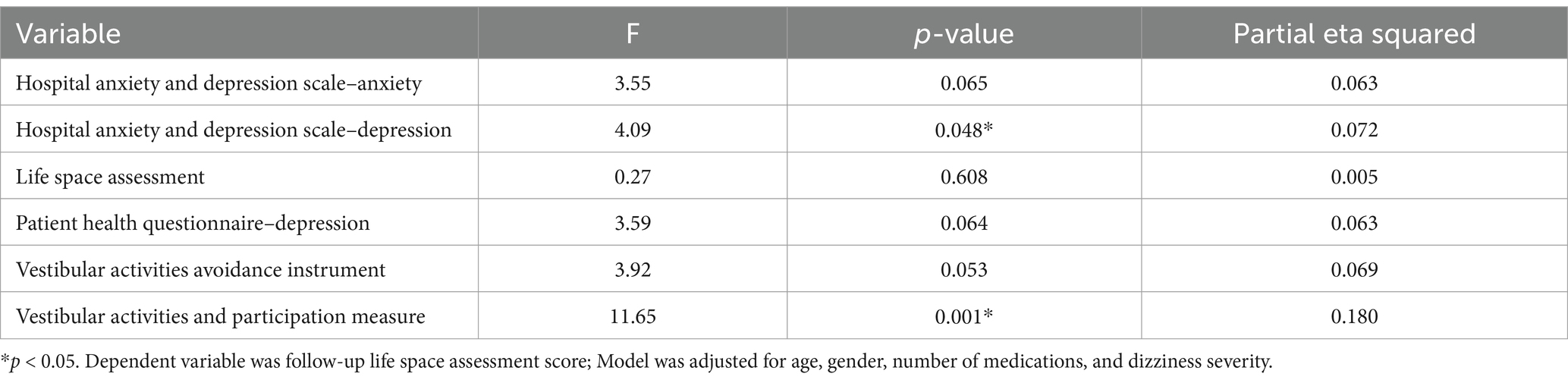

Association between psychosocial factors and community mobilityWe found significant bivariate associations in simple linear regression models between baseline VAAI, HADS-A, HADS-D, PHQ-4 depression subscale, and LSA score at the 3-month follow-up (Table 2). There was also a significant relationship between baseline VAP and LSA score at 3 months. Therefore, we included these measures in the repeated measures ANOVA model for LSA. Upon assessing the association between the independent variables and covariates, we found no correlation coefficients >0.8, providing evidence for lower risk of multicollinearity (27). After controlling for age, gender, dizziness severity, number of medications as well as baseline VAAI, HADS-A, PHQ-4 depression subscale and LSA, we found that the baseline HADS-D (F = 4.09, p = 0.048) and VAP (F = 11.65, p = 0.001) were significantly associated with the total LSA score at the 3-month follow-up visit (Table 3). This indicates that baseline depressive symptoms and activity limitations and participation restrictions were significant predictors of community mobility at 3 months. According to the partial eta squared values, baseline VAP had a large effect (η2 = 0.18), and HADS-D had a moderate to large effect (η2 = 0.07) on community mobility at 3 months.

Table 2. Association between baseline psychosocial factors and community mobility and participation at follow-up.

Table 3. Predictors of community mobility at follow-up among individuals with dizziness.

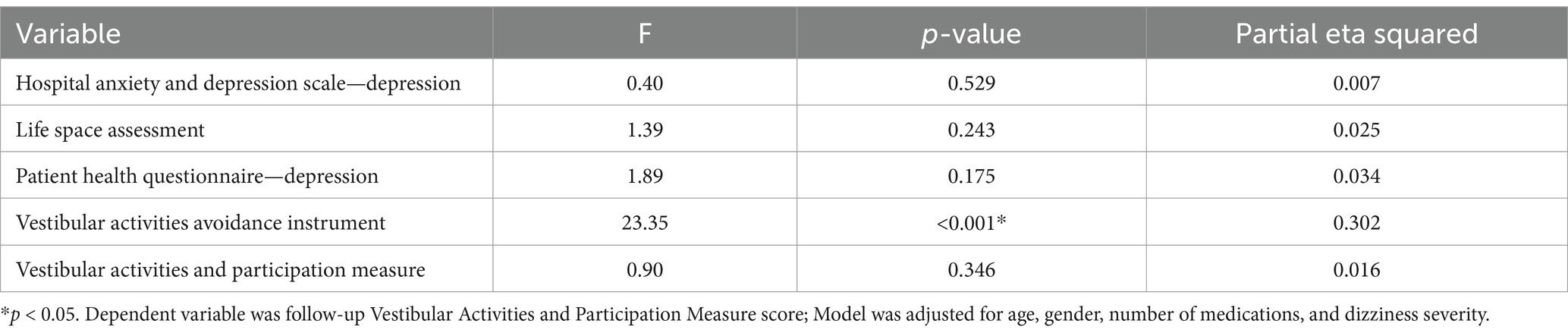

Association between psychosocial factors and activity and participationThere were significant bivariate associations between baseline VAAI, HADS-D, PHQ-4 depression subscale, and the total VAP score at the 3-month follow-up visit (Table 2). We also found a significant association between baseline LSA score and VAP score at 3 months. We included each of these baseline measures as well as baseline VAP into the repeated measures ANOVA model of VAP. Upon assessing the association between the independent variables and covariates, we found no correlation coefficients >0.8, providing evidence for lower risk of multicollinearity (27). We found that baseline VAAI was the only significant predictor of total VAP score at 3-month follow-up after controlling for covariates and other psychosocial factors (F = 23.35, p < 0.001) (Table 4). This indicates that baseline fear avoidance beliefs were a significant predictor of future activity limitations and participation restrictions. According to the partial eta squared value, baseline VAAI had a large effect (η2 = 0.3) on VAP at the 3-month follow-up visit.

Table 4. Predictors of activity and participation at follow-up among individuals with dizziness.

Exploratory factor analysis of psychosocial outcome measuresAccording to Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Χ2 = 2935, p < 0.001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.852), there was a sufficient number of correlated items to conduct the factor analysis. Upon evaluation of the scree plot (Supplementary Figure 1), we found that four factors should be retained. After the direct oblimin factor rotation, most items strongly loaded onto at least one factor (Table 5). Based on the factor loadings, we named the factors as follows: Catastrophization (factor 1), Anxiety (factor 2), Fear Avoidance (factor 3), and Depression (factor 4). One item from the HADS depression subscale did not load strongly on any factor. This item was related to losing interest in appearance. HADS item 8, or feeling slowed down, loaded on the fear avoidance factor. Item 6 from the HADS depression subscale, relating to being cheerful, and Item 4 from the PHQ-4 relating to feeling down, both loaded more strongly on the anxiety factor than the depression factor.

Table 5. Factor loadings for psychosocial measure items among individuals with dizziness.

DiscussionOur findings indicate that various psychosocial factors were associated with future community mobility, activity, and participation. In multivariate models, current depression and activity/participation were significant predictors of future community mobility while fear avoidance was a significant predictor of future activity and participation. Additionally, our results further validate the use of well-established patient-reported outcome measures of psychosocial factors in vestibular rehabilitation in their original formats as they assess several distinct underlying constructs, highlighting the value in employing multiple measures to comprehensively capture psychosocial domain in clinical practice.

Psychosocial factors, community mobility, activity and participationIn this sample of individuals experiencing dizziness we found limited community mobility evidenced by the total LSA score, which is consistent with what we have found previously among persons with dizziness (21). Our findings suggest that greater depressive symptoms and more activity limitations and participation restrictions were significantly associated with limited future community mobility. Previous studies have found associations between psychosocial factors, including depression, and community mobility among older adults (31, 32). Webber et al. (31) included measures of anxiety, depression, loneliness, social support and frequency of community-based activity and participation in the psychosocial component of their model, which was directly associated with community mobility in older adults. In a study of individuals post-vestibular schwannoma resection, researchers found that individuals with chronic dizziness had lower physical activity levels compared to individuals without chronic dizziness and physical activity levels were significantly associated with disability (33). In our previous work we found that reduced community mobility was associated with greater dizziness-related disability and poorer physical and mental quality of life (21). Together, these findings suggest that psychosocial factors such as depressive symptoms and behavioral variables such as lower physical activity levels may adversely affect community mobility and overall quality of life.

Overall, individuals in our sample reported mild activity limitations and participation restrictions at baseline, which improved over 3 months. Fear avoidance beliefs were significantly associated with future activity limitations and participation restrictions after controlling for other factors. In a prospective study including individuals with acute unilateral vestibulopathy, investigators found that fear avoidance and depressive symptoms at baseline were significantly associated with dizziness-related disability at 6 months post-onset (6). Others found cross-sectional associations between psychosocial factors such as distress, symptom focusing, embarrassment avoidance, resting behaviors, fear avoidance beliefs/behaviors and dizziness-related disability (4, 17, 34). In a separate sample of individuals with dizziness, we previously found significant associations between fear avoidance and activity and participation after controlling for other factors, confirming our findings in the present study.

The goals of vestibular rehabilitation are to minimize symptoms and maximize functioning in activities of daily living, normalize balance and gait, and meet the specific needs and goals of the patient (19). The results of this study suggest that identification of psychological factors such as fear avoidance, catastrophic thinking, and clinically significant depression may allow clinicians to incorporate psychologically informed techniques into rehabilitation plans and collaborate with psychologists and psychiatrists when needed to improve patient outcomes. Self-report measures such as those employed in this investigation are simple, validated aids for detecting these factors. Evidence is beginning to accumulate about the benefits of this approach (35). Psychologically informed techniques in vestibular rehabilitation can include graded exposure to reduce fear of movement, goal-setting, promoting self-efficacy, positive reinforcement, enhancing patient perceptions and expectations, distraction and/or relaxation techniques (36–38). To effectively incorporate these techniques into rehabilitation sessions early on in care, it is essential to identify and measure psychosocial factors in this population. Use of psychologically informed care may address some of the psychosocial factors that are associated with reduced activity, participation, and community mobility among individuals with dizziness.

Psychosocial constructs measured using patient-reported outcomesClinicians have a variety of patient-reported outcome measures available to assess and characterize psychosocial factors among individuals experiencing dizziness. The goal of our factor analysis was to identify distinct constructs relevant to patients with dizziness that may be embedded within these tools. The analysis revealed four factors, which we named catastrophization, anxiety, fear avoidance, and depression. Most items strongly loaded onto one factor in keeping with the construction of the original instruments, further validating the use of the psychosocial measures in this population. However, it should be noted that there was one item that did not load strongly onto any factor and two items from the HADS and PHQ depression subscales that loaded more strongly on the anxiety factor.

Previous studies have examined the factor structure of the HADS, DCS, and VAAI but this is the first study that considers these items together in a factor analysis (12, 14, 15). Piker et al. (12) found a 3-factor structure for the HADS in a sample of individuals with dizziness. Pothier et al. (15) found that the items included in the DCS loaded on a single factor, which was consistent with our findings. In our previous work using a separate sample of individuals with dizziness, we found that the VAAI loaded onto a single factor, confirmed by the results of the present study (14). Taken together, the results of the factor analysis indicate that the DCS, the VAAI, the HADS and PHQ anxiety and depression subscales are all applicable to patients with dizziness without modification, but they also suggest that each captures a different dimension of behavioral morbidity. Thus, there may be benefits in selecting multiple measures to fully capture psychosocial constructs such as catastrophizing, anxiety, fear avoidance, and depression. Given our findings of associations between fear avoidance and depression with activity, participation, and community mobility, these constructs may be particularly important to assess in clinical settings.

Strengths and limitationsThis study included 100 individuals experiencing dizziness recruited from one tertiary care balance disorders clinic. While this sample size was sufficient to include patients with a variety of illnesses, it may not provide an accurate representation of all individuals seeking care for dizziness. We included several patient-reported outcome measures to characterize psychosocial factors, but we did not presume to capture all aspects of psychosocial functioning and there may be other constructs that contribute to activity, participation, and community mobility but were not measured in this study. We were not able to determine reasons that patients were lost to follow-up at 3-months (n = 32) as we were not able to contact these individuals, so we cannot determine the extent to which that may have introduced non-random selection bias. Despite these limitations, the results of our multivariate analyses fills a gap in knowledge about the effects of psychosocial factors on activity, participation, and community mobility in this population.

ConclusionIn this investigation of psychosocial factors in patients experiencing dizziness, we found that depressive symptoms and activity/participation restrictions emerged as predictors of future community mobility, while fear avoidance beliefs strongly predicted future activity limitations and participation restrictions. A possible implication of these results, to be tested in future investigations, is that timely identification of these factors followed by interventions to address them in patients with dizziness may improve outcomes in physical therapy to include greater engagement in activities and increased community mobility.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsPD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank the participants who dedicated their time to participate in this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1531204/full#supplementary-material

Supplemental Figure 1 | Scree plot for exploratory factor analysis of psychosocial outcome measures in people with dizziness.

References1. Bigelow, RT, Semenov, YR, du Lac, S, Hoffman, HJ, and Agrawal, Y. Vestibular vertigo and comorbid cognitive and psychiatric impairment: the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2016) 87:367–72. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310319

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Wiltink, J, Tschan, R, Michal, M, Subic-Wrana, C, Eckhardt-Henn, A, Dieterich, M, et al. Dizziness: anxiety, health care utilization and health behavior--results from a representative German community survey. J Psychosom Res. (2009) 66:417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.012

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Herdman, D, Norton, S, Pavlou, M, Murdin, L, and Moss-Morris, R. Vestibular deficits and psychological factors correlating to dizziness handicap and symptom severity. J Psychosom Res. (2020) 132:109969. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109969

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Cousins, S, Kaski, D, Cutfield, N, Arshad, Q, Ahmad, H, Gresty, MA, et al. Predictors of clinical recovery from vestibular neuritis: a prospective study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2017) 4:340–6. doi: 10.1002/acn3.386

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. van, L, Hallemans, A, de, C, Janssens, S, Fransen, E, Schubert, M, et al. Predictors of chronic dizziness in acute unilateral vestibulopathy: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2025) 172:262–72. doi: 10.1002/ohn.964

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Dunlap, PM, Sparto, PJ, Marchetti, GF, Furman, JM, Staab, JP, Delitto, A, et al. Fear avoidance beliefs are associated with perceived disability in persons with vestibular disorders. Phys Ther. (2021) 101:147. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab147

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Herdman, D, Norton, S, Pavlou, M, Murdin, L, and Moss-Morris, R. The role of pre-diagnosis audio-vestibular dysfunction versus distress, illness-related cognitions and behaviors in predicted ongoing dizziness handicap. Psychosom Med. (2020) 82:787–95. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000857

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, and Williams, JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Spitzer, RL, Kroenke, K, Williams, JBW, and Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Piker, EG, Kaylie, DM, Garrison, D, and Tucci, DL. Hospital anxiety and depression scale: factor structure, internal consistency and convergent validity in patients with dizziness. Audiol Neurootol. (2015) 20:394–9. doi: 10.1159/000438740

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Herdman, D, Picariello, F, and Moss-Morris, R. Validity of the patient health questionnaire anxiety and depression scale (PHQ-ADS) in patients with dizziness. Otol Neurotol. (2022) 43:e361–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000003460

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Dunlap, PM, Marchetti, GF, Sparto, PJ, Staab, JP, Furman, JM, Delitto, A, et al. Exploratory factor analysis of the vestibular activities avoidance instrument. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2021) 147:144–50. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.4203

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Pothier, DD, Shah, P, Quilty, L, Ozzoude, M, Dillon, WA, Rutka, JA, et al. Association between catastrophizing and dizziness-related disability assessed with the dizziness catastrophizing scale. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2018) 144:906–12. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1863

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Picariello, F, Chilcot, J, Chalder, T, Herdman, D, and Moss-Morris, R. The cognitive and Behavioural responses to symptoms questionnaire (CBRQ): development, reliability and validity across several long-term conditions. Br J Health Psychol. (2023) 28:619–38. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12644

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Kristiansen, L, Magnussen, LH, Wilhelmsen, KT, Maeland, S, Nordahl, SHG, Hovland, A, et al. Self-reported measures have a stronger association with dizziness-related handicap compared with physical tests in persons with persistent dizziness. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:850986. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.850986

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Piker, EG, Jacobson, GP, McCaslin, DL, and Grantham, SL. Psychological comorbidities and their relationship to self-reported handicap in samples of dizzy patients. J Am Acad Audiol. (2008) 19:337–47. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.19.4.6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Hall, CD, Herdman, SJ, Whitney, SL, Anson, ER, Carender, WJ, Hoppes, CW, et al. Vestibular rehabilitation for peripheral vestibular hypofunction: an updated clinical practice guideline from the academy of neurologic physical therapy of the American physical therapy association. J Neurol Phys Ther. (2022) 46:118–77. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000382

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Peel, C, Sawyer Baker, P, Roth, DL, Brown, CJ, Brodner, EV, and Allman, RM. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB study of aging life-space assessment. Phys Ther. (2005) 85:1008–19. doi: 10.1093/ptj/85.10.1008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Alshebber, KM, Dunlap, PM, and Whitney, SL. Reliability and concurrent validity of life space assessment in individuals with vestibular disorders. J Neurol Phys Ther. (2020) 44:214–9. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000320

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Alghwiri, AA, Whitney, SL, Baker, CE, Sparto, PJ, Marchetti, GF, Rogers, JC, et al. The development and validation of the vestibular activities and participation measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2012) 93:1822–31. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.017

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Alghwiri, A, Alghadir, A, and Whitney, SL. The vestibular activities and participation measure and vestibular disorders. J Vestib Res. (2013) 23:305–12. doi: 10.3233/VES-130474

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, Williams, JBW, and Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. (2009) 50:613–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Dunlap, PM, Alradady, FA, Costa, CM, Delitto, A, Terhorst, L, Sparto, PJ, et al. The psychometric properties of the 9-item vestibular activities avoidance instrument. Phys Ther. (2023) 103:pzad094. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzad094

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Hall, CD, and Herdman, SJ. Reliability of clinical measures used to assess patients with peripheral vestibular disorders. J Neurol Phys Ther. (2006) 30:74–81. doi: 10.1097/01.npt.0000282571.55673.ed

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Berry, W, and Feldman, S. Multiple regression in practice. 2455 teller road, thousand oaks California 91320 United States of America. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. (1985).

28. Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1988).

29. Bartlett, MS. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. (1950) 3:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Pett, MA, Lackey, NR, and Sullivan, JJ. Making sense of factor analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2003).

31. Webber, SC, Liu, Y, Jiang, D, Ripat, J, Nowicki, S, Tate, R, et al. Verification of a comprehensive framework for mobility using data from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging: a structural equation modeling analysis. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:823. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04566-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Lo, AX, Wadley, VG, Brown, CJ, Long, DL, Crowe, M, Howard, VJ, et al. Life-space mobility: normative values from a National Cohort of U.S. older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2024) 79:176. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glad176

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

留言 (0)