Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health disorder caused by experiencing or witnessing traumatic events that include exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence (1, 2). Symptoms consist of intrusive memories, avoidant behaviors, increased anxiety, and flashbacks (1, 3). A recent study has shown that 63% of Canadians above the age of 18 will likely experience at least one traumatic event and that approximately 7% of Canadians will screen positive for PTSD during their lifetime (4). Prevalence rates appear similar across the United States (5, 6). This risk of PTSD increases in vulnerable populations including: women (7), military personnel (8), first responders (9) and health care workers (10). As the population grows, the impact of PTSD will continue to increase—understanding this disorder and its neurobiological impact will be increasingly important for treatment.

PTSD is categorized as a Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder and does not have a clear neurobiological cause; yet, emerging evidence suggests that PTSD predisposes individuals to developing dementia later in life (1, 11–13). In fact, it has been suggested that the increased risk of developing dementia following a PTSD diagnosis is 1.5 to 2-fold compared to people without PTSD (14, 15). The increased risk of dementia in PTSD spans a variety of diagnoses including: frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer's disease (AD) (16). The present study focuses on the most prominent cause of dementia (AD), which accounts for approximately 70% of all dementia cases (17).

In contrast to PTSD, which can occur at any age but on average begins in young adulthood to middle-age, AD symptoms typically present around age 65 (18). The biggest risk factor for developing AD is age −47% of people tested above the age of 85 had probable diagnoses of AD (19). PTSD and AD share common symptoms including negative changes in mood and cognition, personality changes, memory difficulties and alterations in arousal or reactivity symptoms (20, 21). A recent study suggests that PTSD symptom severity is associated with accelerated cognitive decline, a leading symptom of AD (22).

Although the neurobiological underpinnings of PTSD have been difficult to isolate, a recent meta-analysis identified several brain regions that have been shown to have reduced gray matter (GM) volume, including the medial frontal gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), and insula (23). Furthermore, significant correlations have been observed between increased PTSD symptom severity and decreased GM volume within the temporal lobe, and most commonly in the hippocampus (24–26). Interestingly, AD also typically shows neurodegeneration in the medial temporal lobe, hippocampus and amygdala (27–31). In addition to these memory-related brain regions, AD can also be characterized by decreased activity (cerebral blood flow [CBF] or metabolism) in the frontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex (32–36) which are also commonly found in PTSD (37–40). These overlapping neuroimaging findings may point to a mechanism for the increased risk of AD following a PTSD diagnosis.

Currently, no biomarkers are available to identify which patients with PTSD will progress to AD. This study explores different neuroimaging modalities to investigate possible neural biomarkers of dementia in a high-risk population. In this study, we characterize GM volume and CBF differences between PTSD and HC groups, then apply two machine learning algorithms across two neuroimaging modalities to estimate AD-like Brain Structure (ABS) scores (41) and AD-like activity pattern (Machine learning-based AD Designation [MAD]) scores (42) in PTSD. MAD scores indicate how similar a patient's brain activity is to AD patterns of brain activity—the higher the score, the greater the similarity. The MAD algorithm was originally trained using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) data of 94 patients with AD and 111 age-matched HC from the AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; http://adni.loni.usc.edu/) database. MAD has been shown to be compatible with CBF images derived from perfusion SPECT (42) and pCASL data (43). Furthermore, MAD scores have been shown to increase over time only in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who later progress to dementia—MAD scores of patients with stable MCI remained stationary (44). Finally, MAD scores were also elevated in patients with epilepsy experiencing cognitive decline, compared to cognitively intact patients with epilepsy (45), suggesting its utility in identifying at-risk individuals with comorbidity.

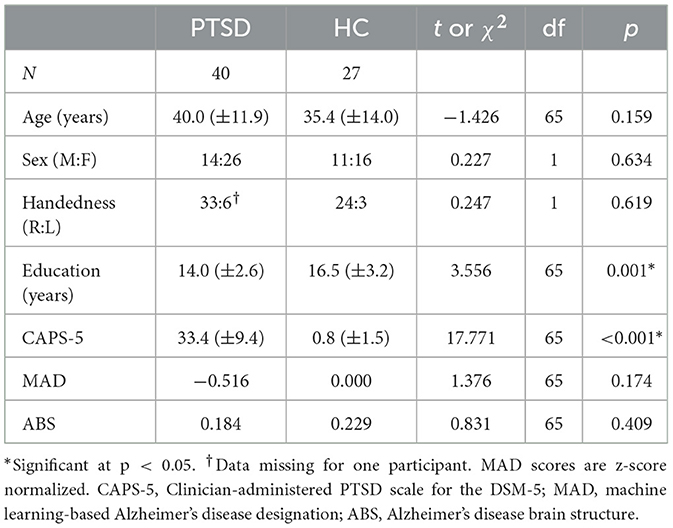

Materials and methods ParticipantsA total of 67 participants aged 18–65 were recruited for the open-label, non-randomized parallel clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03229915)—only baseline data were used for the present study. Two groups were included in this study: PTSD (n = 40) and HC (n = 27). Patients in the PTSD group were treatment-seeking individuals who had experienced a criterion A traumatic event. The HC group consisted of trauma-naïve (TNC; n = 15) and trauma-exposed (TEC; n = 12) participants; due to low sample size TEC and TNC groups were pooled. TEC participants met CAPS-5 Criterion A (i.e., exposure to a traumatic event), while obtaining a CAPS-5 total severity score of ≤ 5. Demographic data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and CAPS-5 data for PTSD and HC groups.

Exclusion criteria for all participants included substance dependence not in remission for at least 3 months, uncontrolled bipolar or psychiatric disorder, history of panic attacks, heart disease, respiratory distress, or neurological conditions including traumatic brain injury (TBI), as well as any MRI contraindications (e.g., metal implants or pregnancy). The CAPS-5 interview was administered to all participants to assess PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity (see Table 1). This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba and performed according to regulations. Participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study and received an honorarium for their time.

MRI acquisitionMRI scans were acquired from all participants to investigate brain structure and function. Scans were acquired using a 3 Tesla, 12-channel Siemens MAGNETOM Verio MRI scanner (Erlangen, Germany) at the Kleysen Institute for Advanced Medicine in Winnipeg, Canada. Imaging acquired during each session included an anatomical T1-weighted scan (MPRAGE sequence; TR/TE/TI = 2,300/3.02/900 ms; flip angle = 9°; field of view (FOV) = 256 mm × 256 mm with 1.00 mm × 1.00 mm × 1.00 mm resolution; 240 slices), a resting state functional T2*- weighted scan (scan duration = 11 min; results forthcoming elsewhere), and a pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling scan (pCASL; TR/TE = 4,000/12 ms; flip angle = 90°; FOV = 240 mm × 240 mm with 3.8 mm × 3.8 mm × 5 mm resolution; 90 volumes; 20 slices; slice thickness = 5; inter-slice gap = 1 mm; labeling time = 2 s; post label delay time = 1.2 s; bandwidth = 3 kHz/pixel). M0 images were also acquired (TR/TE = 8,000/12 ms) to calibrate the pCASL images.

Structural MRI analysisStructural T1-weighted images were preprocessed using the CAT12.8.2 toolbox (r2170; https://neuro-jena.github.io/cat/index.html) using SPM12 software (version 6909, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). First, a robust bias correction was applied to the MRI scans to reduce intensity variations. Then, the scans were segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid maps and spatially normalized into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space (voxel size 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm) using the DARTEL algorithm. Modulation was applied to keep the volume information accurate. For VBM analysis, we smoothed the modulated GM images with an 8 mm3 full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

In order to detect any morphological differences in GM between individuals with PTSD and HC, we conducted a two-sample t-test on the smoothed GM images using SPM12 software. Age, sex, and total intracranial volume (TIV) were included as covariates during the analysis. An explicit mask, comprised of an average of all participant's GM masks, was used to limit search regions inside the GM of the brain. Results are considered significant at a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.001 (uncorrected) and a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05, corrected using family-wise error (FWE). Individual-level mean GM volumes were extracted from the significant clusters for further correlational analyses.

We estimated the previously described ABS scores (41) utilizing the region-based morphometry feature in CAT12 to obtain whole-brain GM volumes based on the neuromorphometrics atlas (www.neuromorphometrics.com; 136 regions in total), along with subregions of the hippocampus (18 regions) (46) and the cerebellum (26 regions) (47). Additionally, cortical thickness (CT) measurements were assessed using the Desikan-Killiany-Tourville (DKT) atlas, which defines 34 regions of interest in each cerebral hemisphere (48). In order to adjust for variations in brain size, the volumes of each subject were normalized by respective TIV. TIV was determined using the CAT12 toolbox (49). Utilizing the aforementioned brain structure-describing information, ABS ranks the most relevant features for classifying AD vs. HC based on a support vector machine (SVM) (41). The details of ABS model replication and validation are included in the Supplementary material.

CBF analysisFor the CBF analysis, pCASL images were preprocessed using the default parameters of the ASLtbx (https://www.cfn.upenn.edu/zewang/ASLtbx.php) (50). First, data were realigned, then co-registered to the structural T1-weighted image, segmented and spatially normalized to standard MNI space (using nonlinear normalization by applying the deformations from the structural CAT12 analysis), and smoothed with an 8 mm3 FWHM Gaussian kernel, as described previously (51). Mean CBF images were produced and contrasted between the groups using SPM12. Age and sex were included as covariates. An explicit mask using the average whole-brain map of all participants was used to limit search regions within the brain. Results are considered significant at a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.001 (uncorrected) and a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05, corrected using FWE. Mean regional CBF values were extracted from significant clusters for further correlational analyses.

The smoothed mean CBF images were further assessed using our previously developed MAD algorithm (available at: https://www.kolabneuro.com/software1) (42). In the original work, out of the five different algorithms tested, the SVM with iterative single data algorithm (ISDA) was the best-performing machine (84% sensitivity and 95% specificity) for distinguishing between AD and HC—this algorithm was used in the present study (42).

Statistical evaluationStatistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corp., version 27.0, Armonk NY) software. Demographic data were assessed using independent t-test or chi2, as appropriate (Table 1). Additionally, correlations between neuroimaging data (significant clusters in GM and CBF whole-brain analyses and MAD and ABS scores) and CAPS-5 total severity scores were assessed. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

ResultsPTSD and HC groups did not significantly differ for age or sex (Table 1). CAPS-5 scores and years of education significantly differed between groups (Table 1)—the PTSD group had higher PTSD symptom severity scores (t(65) = 17.771, p < 0.001), as expected. Additionally, the PTSD group on average had fewer years of education (t(65) = 3.556, p = 0.001). Sex, age, and TIV (GM volume analyses only) were used as covariates throughout the study.

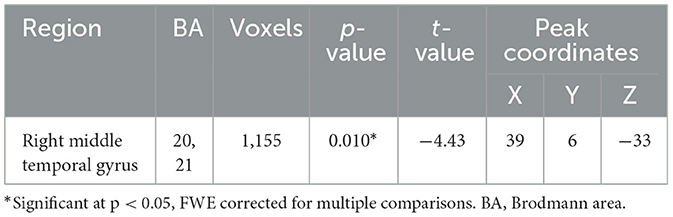

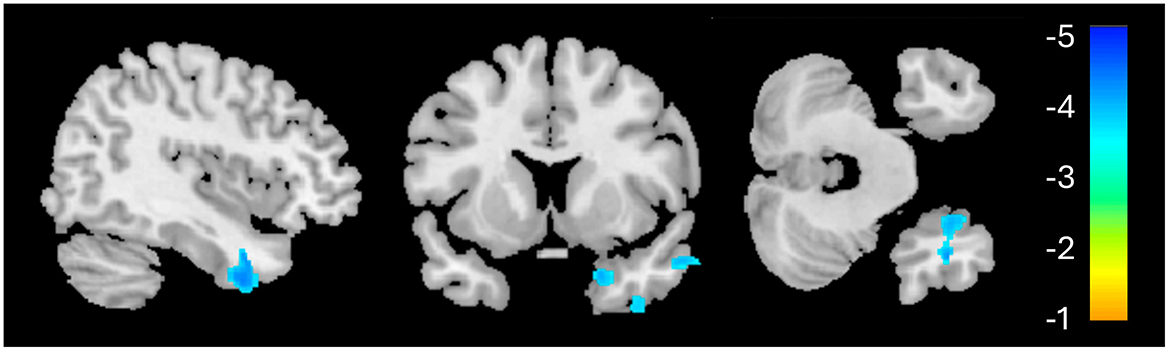

GM volumesReduced volume was observed in the right middle temporal gyrus/parahippocampal gyrus for the PTSD group, compared to the HC group (Table 2, Figure 1). No regions showed significantly larger volume for the PTSD group, compared to the HC group. GM volume of the middle temporal gyrus cluster correlated with CAPS-5 total symptom severity scores (r = −0.461; p = 0.005; Figure 2).

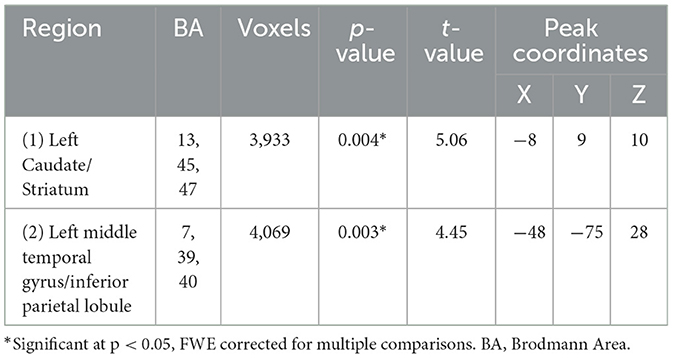

Table 2. Whole-brain volume-based morphometry differences between groups (PTSD > HC), using age, sex, and total intracranial volume as covariates.

Figure 1. Whole-brain voxel-based morphometry results for the PTSD > HC contrast. The significant cluster (1,155 voxels) is identified in blue, indicating reduced volume in this region for the PTSD group, relative to HC.

Figure 2. Correlation results. Medial temporal lobe volume correlates with CAPS-5 scores (left) and standardized MAD scores (right) in the PTSD group (teal, filled circles), but not the HC group (black, empty triangles).

ABS scores did not show any significant difference between the PTSD and HC groups (t(65) = 0.831, p = 0.409). Further evaluation using a proportions z-test indicated that 11.1% (3/27) of the HC group and 7.5% (3/40) of the PTSD group were classified as AD-like, resulting in a z-statistic of 0.508, p = 0.612 (proportional difference = 3.61%, 95% CI = [−10.78%, 18.00%], Cohen's d = 0.1259), indicating no statistically significant difference between the groups.

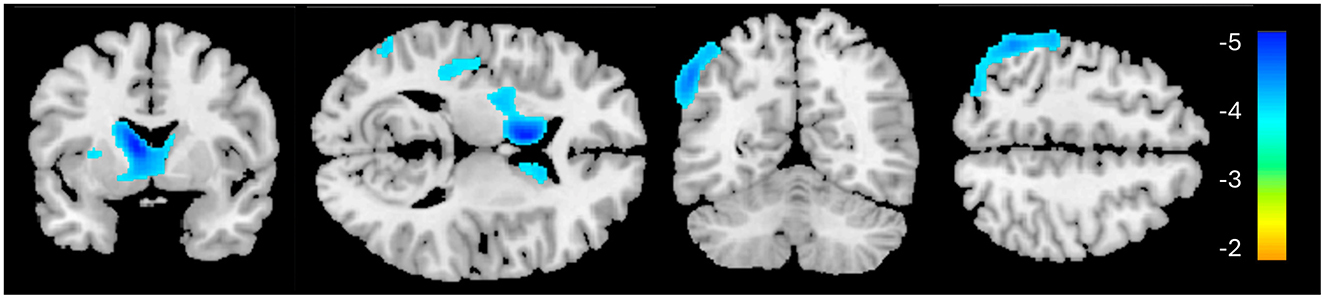

CBFThe PTSD group showed significantly lower CBF in two clusters, primarily in the left hemisphere, compared to the HC group (Table 3, Figure 3). The first cluster (3,933 voxels) had peak coordinates in the caudate and striatum and extended to the insula, parahippocampal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, limbic lobe and amygdala. The second cluster (4,069 voxels) peaked within the middle temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule and extends to the pre- and postcentral gyri. There was no significantly increased CBF for the PTSD group, compared to the HC group. The mean CBF values of either cluster did not correlate with CAPS-5 total severity scores.

Table 3. Whole-brain cerebral blood flow differences between groups (PTSD < HC), using age and sex as covariates.

Figure 3. Whole-brain cerebral blood flow results for the PTSD > HC contrast. Significant clusters are identified in blue, indicating reduced cerebral blood flow in these regions for the PTSD group, relative to HC.

MAD scores did not significantly differ between groups [t(65) = 1.376, p = 0.174]. At the individual level, five of the PTSD patients showed MAD scores (z-score) higher than 1.96 (p < 0.05), compared to none of the HC participants (χ2 = 3.647, p = 0.076). MAD scores correlated with GM volume in the significant middle temporal gyrus cluster identified above (r = −0.423; p = 0.010; Figure 2). A non-significant trending correlation was also observed between MAD scores and CAPS-5 total severity scores (r = 0.302, p = 0.065). Other correlational analysis results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

DiscussionThe goal of the present study was to find a novel non-invasive early neurological marker of AD in PTSD. We used machine learning algorithms (MAD and ABS) paired with neuroimaging and clinical variables to investigate these markers. The combination of these algorithms and PTSD symptom severity scores (CAPS-5) allowed us to identify a significant region of decreased brain volume in PTSD, associated with greater similarity to AD resting brain activity. Interestingly we noticed these markers in a PTSD participant group whose ages are younger than the typical age of diagnosis of AD.

As expected, and consistent with diagnostic criteria, there was a significant difference in CAPS-5 total symptom severity scores between the PTSD group and HC group, indicating increased PTSD symptom severity in the PTSD group (1, 52, 53). The CAPS-5 total severity scores were used as our primary psychiatric variable throughout the study. Additionally, education significantly differed between groups (Table 1), which is not surprising given that many of the participants in the PTSD group had careers as public safety personnel, typically requiring fewer years of formal education than our HC cohort, which had higher than average years of education.

Structural neuroimaging results identified one region of significantly reduced GM volume for the PTSD group, compared to the HCs (Figure 1). This middle temporal gyrus cluster included the parahippocampal cortex and Brodmann's areas (BA) 20 and 21 (Table 2). BA 20 is typically associated with processing visual information and memory association while BA 21 is involved in semantic memory processing, language processing and visual perception (54). Taken together, reduced volume within these regions may be associated with the experience of traumatic events and the ability to recall these memories (3, 55), and may be involved in symptoms such as flashbacks and accurate memory retention of traumatic events (1, 52). This result of decreased volume in the middle temporal lobe, more specifically the hippocampus and surrounding regions, is a common finding among PTSD structural neuroimaging results (56–58).

Interestingly, GM volume within this region was significantly, negatively correlated with CAPS-5 scores—smaller volume in this region was associated with greater symptom severity—a finding corroborated in the literature (24, 25). Furthermore, reduced GM volume in the temporal lobe cluster also correlated with MAD scores. In AD, the middle temporal lobe is the first region to begin showing neurodegeneration (30, 59), corresponding to the defining symptom of AD: memory deterioration (60). Although a causal role cannot be determined by the present study, it may be the case that individuals with reduced volume in this middle temporal region may be more susceptible to developing AD (as well as PTSD). Alternatively, trauma and the effects of PTSD may cause neurodegeneration in this region that increases the risk of dementia later in life. However, it is interesting to note that recently, psychological trauma in an animal model induced GM volume reduction in the hippocampus and globus pallidum (61). Further large-scale longitudinal investigations such as the UK Brain Bank (https://ukbbn.brainsfordementiaresearch.org) and Biofinder (https://biofinder.se/) should be used to shed more light on causality.

Topographically, MAD scores are determined by the overall whole-brain metabolic pattern, which is projected to a hyperplane used to differentiate between AD and HC (42). This hyperplane was largely characterized by hypometabolism in temporal regions. Therefore, it is not surprising that the regional GM reduction in the temporal regions observed in the present study correlated with increasing MAD scores in PTSD (Figure 2). While it remains to be seen whether there is any causal relationship between the location of the GM deterioration and AD progression, the lack of significant correlation within the HC group suggests that the medial temporal lobe may be an important region for predicting AD-risk in PTSD.

None of the ABS scores, which focus on AD-like structural patterns, correlated with any other neuroimaging results (GM, CBF, or MAD) or symptom severity (CAPS-5). Although the regional GM deficiency revealed by VBM analysis (Figure 1) spatially overlapped with features used in ABS classification, it should be noted that it does not constitute that they reflect the same pathology. The local GM difference between HC and PTSD groups was highly localized and it primarily reflects the PTSD-related changes (hence correlated with CAPS-5). On the contrary, ABS scores did not differ between groups. The relatively small regional atrophy in the right middle temporal lobe in our cognitively healthy PTSD sample may have not been sufficient to affect ABS scores, which capture the entire brain structural changes associated with AD. Nevertheless, the MAD score was correlated with regional GM changes. This observation is in line with the finding that AD-specific structural changes appear to occur after the functional (and/or vascular) changes (62).

Previously, alterations in CBF have been shown in PTSD, including increased activation in the amygdala (63) and decreased activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the inferior frontal gyrus (64). Our current results identified decreased CBF within the left caudate and striatum; this large cluster additionally encompassed the inferior frontal gyrus and insula—these findings confirm previous CBF findings of decreased activity in these cortical regions (64–67). Interestingly, research suggests that the insula and inferior frontal gyrus have become target stimulation regions for improving attentional decline in AD (68).

The second cluster, showing significantly reduced CBF in the left middle temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule in the PTSD group corresponds with the frontoparietal network (FPN; also known as the central executive network), a resting state network associated with attention and executive processing. Previous neuroimaging studies showed both increased (69–71) and decreased activity (65, 72–75) within this region in PTSD. Discrepancy in activity within this region in the literature may be due to several factors: first, whether resting metabolic/CBF or task-related activity are considered, as outlined, second, some studies have found reduced activity within the left IPL in the acute stage following traumatic exposure, when exposed to trauma-related (76) or fear-learning stimuli (77). In fact, left IPL activity in the acute phase was negatively correlated with symptom severity 3 months later (77).

The regional CBF did not correlate with MAD scores. Similar to the above interpretation for the lack of significant correlation between regional GM volumes and ABS scores, the reduced regional CBF, which reflect PTSD-related changes, may have not been sufficient to influence the MAD scores, which reflect the risks of dementia. It should also be noted that CBF images are much noisier than GM images, the regional change of which has shown to be correlated with MAD scores.

Limitations of this study include that its design was cross-sectional in nature; longitudinal study is required to confirm if patients with these identified neurological patterns go on to develop dementia, and more specifically, AD. We also acknowledge that there may be a selection bias for the HC groups as many of these participants were recruited by word of mouth and advertisements within the hospital and university settings, which may contribute to the higher years of education observed in this sample.

We used MAD scores for assessing AD-associated brain activity changes and ABS for assessing AD-associated brain structural changes. MAD was correlated with GM volume reduction in the medial temporal area which was correlated with PSTD symptom severity measured by CAPS-5. ABS was not correlated with any other measures. Taken together, as symptom severity increases, the brain structure and function become more AD-like, in the PTSD group—it is possible that these individuals who have higher MAD scores may be more susceptible to developing AD in the future. The data presented in our study are more poignant when the average age of our PTSD sample (i.e., 40.0 years) is considered—neurodegeneration in AD typically begins around 55 years of age (78). Early identification of individuals at an increased risk for developing dementia later in life is important for implementing disease-modifying preventative care.

In the current study, we used machine learning for early detection of markers associated with AD in PTSD. This study may provide information that will allow for a better understanding of brain structure and function in PTSD and how it may relate to the progression and possible increased risk of AD and dementia. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses machine learning to assess the defining characteristics of AD within a PTSD population using neuroimaging.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Review Board of University of Manitoba. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsGY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TK: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. NW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Resources. IB: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. EC: Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. LR: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. SC: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. RP: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JK: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding support was provided by the Workers Compensation Board of Manitoba (grant number 16-03), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2016-05964; RGPIN-2023-04283; PDF-2020-545615), and the University of Manitoba.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors also wish to thank all research participants who contributed to this study and the staff members of MRI units at the Health Sciences Centre for accommodating research setup.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1470727/full#supplementary-material

References1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders : DSM-5-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. (2022).

3. Brewin C. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the brain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2013) 84:e1–e1. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306103.3

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Schein J, Houle C, Urganus A, Cloutier M, Patterson-Lomba O, Wang Y, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. (2021) 37:2151–61. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1978417

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Raut SB, Marathe PA, Van Eijk L, Eri R, Ravindran M, Benedek DM, et al. Diverse therapeutic developments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) indicate common mechanisms of memory modulation. Pharmacol Therapeut. (2022) 239:108195. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108195

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1993) 61:984–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.984

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Yehuda R, Hoge CW, Mcfarlane AC, Vermetten E, Lanius RA, Nievergelt CM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2015) 1:15057–15057. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.57

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Lewis-Schroeder NF, Kieran K, Murphy BL, Wolff JD, Robinson MA, Kaufman ML. Conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of traumatic stress in first responders: a review of critical issues. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 26:216–27. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000176

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell'oste V, Cordone A, Bertelloni CA, Bui E, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113312. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, Barnes DE, Covinsky KE, Neylan T, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among U.S. veterans. Alzheimer's Dementia. (2009) 5:P104. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.05.326

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Monfort E, Trehel G. Post-traumatic stress disorder secondary to Alzheimer's disease: Emergence of an underlying pathology in the oldest old. Annales médico psychologiques. (2017) 175:776–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2017.03.020

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Desmarais P, Weidman D, Wassef A, Bruneau M-A, Friedland J, Bajsarowicz P, et al. The interplay between post-traumatic stress disorder and dementia: a systematic review. Am J Geriatric Psychiat. (2020) 28:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.08.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Günak MM, Billings J, Carratu E, Marchant NL, Favarato G, Orgeta V. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. (2020) 217:600–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.150

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Song H, Sieurin J, Wirdefeldt K, Pedersen NL, Almqvist C, Larsson H, et al. Association of stress-related disorders with subsequent neurodegenerative diseases. JAMA Neurol. (2020) 77:700–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0117

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Mohlenhoff BS, O'donovan A, Weiner MW, Neylan TC. Dementia risk in posttraumatic stress disorder: the relevance of sleep-related abnormalities in brain structure, amyloid, and inflammation. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2017) 19:1. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0835-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Moya-Alvarado G, Gershoni-Emek N, Perlson E, Bronfman FC. Neurodegeneration Alzheimer's disease (AD). What Can Proteomics Tell Us About the Alzheimer's Brain? Mol Cellular Proteom. (2016) 15:409–25. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R115.053330

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Scherr PA, Cook NR, Chown MJ, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons: higher than previously reported. JAMA. (1989) 262:2551–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430180093036

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Prieto S, Nolan KE, Moody JN, Hayes SM, Hayes JP. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts cognitive decline beyond the effect of Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in Veterans. Transl Psychiatry. (2023) 13:102. doi: 10.1038/s41398-023-02354-0

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Siehl S, Zohair R, Guldner S, Nees F. Gray matter differences in adults and children with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 113 studies and 11 meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. (2023) 333:489–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.028

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. (2002) 5:1242–7. doi: 10.1038/nn958

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Villarreal G, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Driscoll I, Rowland LM, Griego JA, et al. Reduced hippocampal volume and total white matter volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiat. (2002) 52:119–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01359-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Harnett NG, Goodman AM, Knight DC. PTSD-related neuroimaging abnormalities in brain function, structure, and biochemistry. Exp Neurol. (2020) 330:113331–113331. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113331

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Frisoni GB, Fox NC, Jack CR, Scheltens P, Thompson PM. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nature Rev Neurol. (2010) 6:67–77. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.215

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. De Flores R, Das SR, Xie L, Wisse LEM, Lyu X, Shah P, et al. Medial temporal lobe networks in Alzheimer's disease: structural and molecular vulnerabilities. J Neurosci. (2022) 42:2131–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0949-21.2021

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Syed GMS, Eagger S, O'brien J, Barrett JJ, Levy R. Patterns of regional cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer's disease. Nucl Med Commun. (1992) 13:656–63. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199209000-00004

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Alsop DC, Detre JA, Grossman M. Assessment of cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer's disease by spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. (2000) 47:93–100.

34. Roher AE, Debbins JP, Malek-Ahmadi M, Chen K, Pipe JG, Maze S, et al. Cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer's disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2012) 8:596–611. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S34874

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Ortner M, Drost R, Heddderich D, Goldhardt O, Müller-Sarnowski F, Diehl-Schmid J, et al. Amyloid PET, FDG-PET or MRI? - the power of different imaging biomarkers to detect progression of early Alzheimer's disease. BMC Neurol. (2019) 19:9. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1498-9

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Thakur M, Snekhalatha U. Multi-stage classification of Alzheimer's disease from 18F-FDG-PET images using deep learning techniques. Physi Eng Sci Med. (2022) 45:1301–15. doi: 10.1007/s13246-022-01196-2

留言 (0)