Chronic childhood skin diseases like psoriasis require prolonged treatment and multiple visits to the hospital can have a considerable impact on the psychological and social health of children and their caregivers.1 About 33% of psoriasis patients develop the disease in the first two decades of life. Incidence increases with age and is reported to be 0.55% in the first decade and 1.37% in the second decade of life.2,3 Caregivers are often anxious and stressed about the future of their child and it has a deep impact on the physical, functional and psychosocial aspects of their lives.4,5 The psychosocial impact of the disease and the continuous care it demands may in turn affect the care rendered by caregivers for the child. Basra & Finlay developed the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI) to assess the impact of a patient’s dermatologic condition on family members’ quality of life (QoL).6,7 The present study estimates the impact of childhood and adolescent chronic plaque psoriasis on cohabitating first-degree caregivers and identifies the level and domains in which the lives of children and their family members are affected.

MethodologyA cross-sectional study was performed to investigate the impact of paediatric psoriasis on the quality of life of affected children and their primary caregivers. Approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee (Ethical reference number: NK/7152/Study/106). Patients with psoriasis suffering for ≥6 months, aged 4–16 years and their attending primary caregivers aged ≥18 years who presented to the dermatology out-patient department between July 2021 and June 2022 were enrolled after written informed assent and consent were provided by the patients and caregivers, respectively. The sample size of 168 was calculated using the formula [N = z2*p*(1−p)/d2)] with ‘N’ being the sample size, z of 1.96 for 95% confidence interval, prevalence (p) of 12.5% and margin of error (d) of 5%; however, 102 patients and caregivers agreed to participate during the study period.8 Caregivers were excluded if they did not live in the same household or reported having any skin diseases or other significant illnesses that could affect their quality of life.

Data regarding patient’s characteristics like age, sex, education, duration of illness, treatment received and response to the treatment, history of relapse, family history of psoriasis, comorbidities, site of involvement, nail and joint involvement and treatment expense were recorded along with the socio-demographic details of the primary caregiver. Expenses were considered catastrophic when annual treatment expenditure was greater than 10% of annual income.9 Response to treatment with current therapy was patient-reported and arbitrarily considered to be minimal, moderate and good. The severity of psoriasis was assessed based on the body-surface-area (BSA) affected and the psoriasis area severity index (PASI).

The impact of psoriasis on the QoL of the children over the last week was determined by using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).10 The cartoon format and text-only format were used for younger children and older children, respectively. Similarly, the validated English and Hindi (local language) versions of the FDLQI questionnaire were used to assess the QoL of caregivers over the last month.6 The CDLQI and FDLQI forms were provided to the patient and caregiver and questions were explained to them in a quiet area. Younger children who were unable to complete the form by themselves were assisted by parents.

Both scales are self-reporting 10-item questionnaires used to assess the impact of skin disease on the QoL with a scoring range from 0 to 30. Higher scores represent greater impairment in the QoL. Each question is scored from 0 to 3 points and requires one response from four separate options, i.e., not at all/not relevant with a score given 0; a little with a score given 1; quite a lot with a score given 2; very much with a score given 3. Final scores are calculated by the sum of ten items. A score between 0 and 1 was considered to have no effect, a score between 2 and 6 was considered to have a small effect, a score between 7 and 12 was considered to have a moderate effect, a score between 13 and 18 was considered to have a very large effect and a score between 19 and 30 was considered to have an extremely large effect.

In the descriptive statistics mean, standard deviation (SD), median, frequency and ratio values were calculated. The normality of distribution of variables was measured with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to analyse differences between independent samples. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used for correlations. Chi-square was used for the association between ordinal variables. Multiple linear regression was used to analyse factors affecting dependent continuous variables. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23(IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

ResultsA total of 102 patients (65 boys, 37 girls) and their caregivers participated during the study period. Median age of children was 13 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 9–16 years, while the median age of caregivers was 29 (IQR 25–32). Sixty-two of them were mothers and forty were fathers of the affected children. Median duration of illness was 3 years (IQR 1.5–4), median percentage body-surface-area of involvement was 5 (IQR 2–10) and median PASI score was 3.4 (IQR 2.2–6.9) [Table 1]. Joint involvement was present in 12 (11.7%) children. Forty-one (40.2%) patients reported good response to treatment, 38 (37.2%) reported moderate response, 21(20.6%) reported minimal response and 2 (1.9%) reported no response to the current drug therapy. Thirty-nine (38.2%) patients received systemic therapy and the rest received topical therapy. In the systemic treatments, fifteen (14.7%) patients received methotrexate, fourteen (13.7%) acitretin, four (3.9%) apremilast and three (2.9%) were treated with cyclosporine.

Table 1: Clinico-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Patients Family membersGender

Male: 65

Female: 37

Relationship

Father: 40

Mother: 62

Age (years):

Mean: 12.05 ± 3.6

Median: 13 (IQR 9–16)

Range: 4–16

Age (years):

Mean: 29.60 ± 5.30

Median: 29 IQR (25–32)

Range: 22–46

Education

Pre-Primary: 6

Primary: 24

Middle School: 28

High school: 21

Higher Secondary: 23

Education

Illiterate: 4

Can read and write: 23

High school: 26

Graduate: 40

Post-graduate: 9

Duration of illness (years)

Mean: 3.43

Median: 3 (IQR 1.5–4)

Range: 0.5–15

Occupation

Housewife 52

Daily-wager 8

Private job 17

Government job 12

Business 13

PASI

Mean: 6.38 ± 7.66

Median: 3.4 (IQR 2.2–6.9)

Range: 1.2–41.8

BSA

Mean: 10.84 ± 15.49

Median: 5 (IQR 2–10)

Range: 1–70

Exposed area affected 68 Nail Involvement 39 Joint Involvement 12CDLQI

Mean: 9.50 ± 8.34

Median: 7 (IQR 2–15.25)

Range: 0–29

FDLQI

Mean: 12.08 ± 8.31

Median: 11 (IQR 4–19)

Range: 1–30

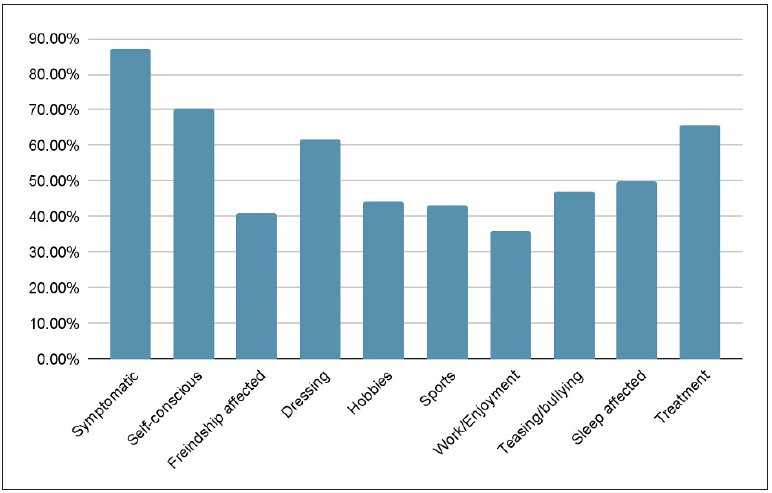

Overall, 87 (85.29%) children had impairment in the CDLQI (represented by a score of ≥2). Children had a median CDLQI of 7 with a range of 0–29 (IQR 2–15.2). Small effect on CDLQI was seen in 35 (34.3%) patients, followed by an extremely large effect in 19 (18.6%) patients [Table 2]. CDLQI n items such as ‘symptoms’ in 89 (87.2%), followed by ‘self-conscious’ in 72 (70.5%) and ‘treatment’ in 67 (65.6%) were the most affected domains. ‘Schooling/work’ was affected in 37 (36.2%) children [Figure 1].

Table 2: Severity of impact on quality of life of children and caregiver

Severity strata CDLQI score (n) % FDLQI score (n) % No effect (0–1) 15 (14.7) 4 (03.9) Small effect (2–6) 35 (34.3) 31 (30.3) Moderate effect (7–12) 17 (16.6) 21 (20.5) Very large effect (13–18) 16 (15.6) 20 (19.6) Extremely large effect (19–30) 19 (18.6) 26 (25.4)

Export to PPT

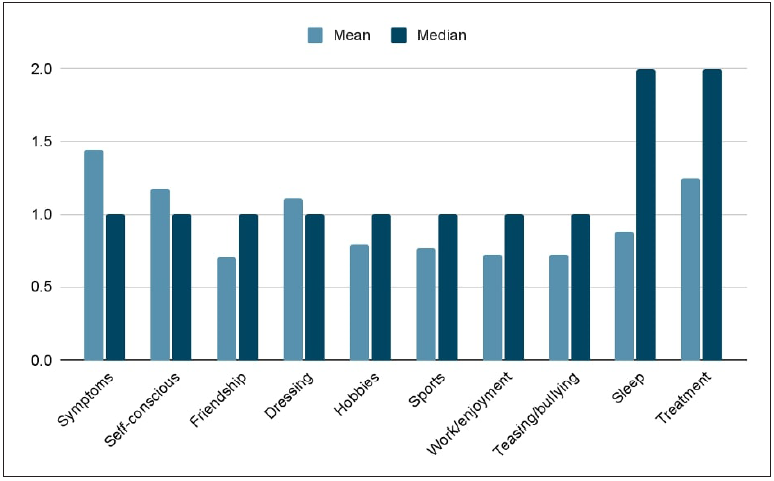

Item ‘symptoms’ had the highest mean (1.44 ± 0.96) score among all the CDLQI items, while schooling/work had a mean score of 0.62 ± 0.99. The median scores were the highest for sleep and treatment items with a value of two for both [Figure 2]. Comparison of male with female patients and of those aged ≤10 with more than 10 showed no statistically significant differences in the CDLQI scores.

Export to PPT

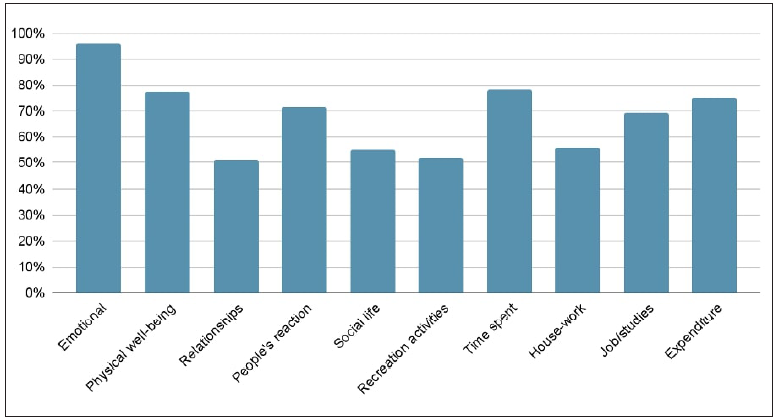

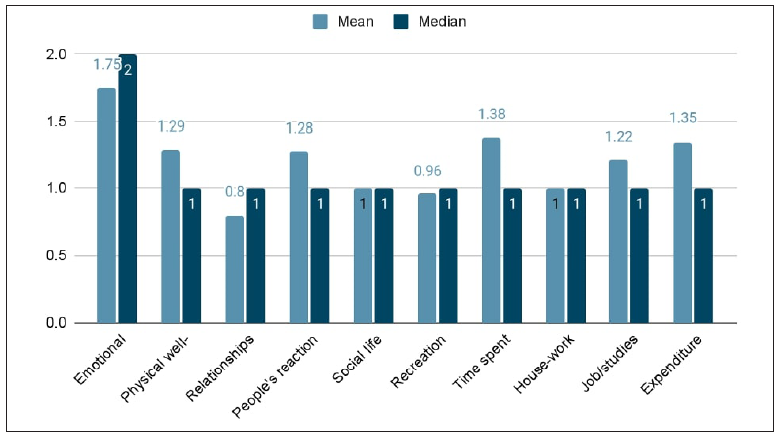

FDLQI was impaired in 98 (96.1%) caregivers (represented by a score of ≥2). The Median FDLQI score was 11 (IQR 4–19). Small effect was seen in 31 (30.3%) caregivers followed by extremely large effect in 26 (25.4%). Most affected FDLQI items were ‘emotional’ in 97 (95%), followed by ‘time spent’ in 80 (78.4%) and ‘physical well-being’ in 79 (77.4%) caregivers [Figure 3]. The highest score was with the emotional item of FDLQI (mean −1.75 ± 0.88; median −2), followed by ‘time spent/ burden of care’ (mean 1.38 ± 1.01; median −1) [Figure 4].

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

A statistically significant correlation was noted between the overall CDLQI score and the overall FDLQI score (p–0.001; rs = 0.790). The Median FDLQI for male children was 11, while for female children it was 9. Similarly, the median CDLQI for the male and female children was 7 and 9 respectively and the differences in the median of FDLQI (p-0.793) and CDLQI (p-0.736) was not significant. The median score of FDLQI in mothers versus fathers was not found to be significant (p-0.717).

PASI had a significant correlation with overall CDLQI score [p-0.001; rs (spearman correlation coefficient) = 0.549] and FDLQI score (p-0.001; rs = 0.609). Similarly, joint involvement correlated significantly with nail involvement (p–0.031; rs = 0.214), CDLQI (p-0.007; rs = 0.196) and FDLQI (p-0.049; rs = 0.196). However, nail involvement did not correlate significantly with CDLQI and FDLQI. Joint involvement was associated with a significant impairment in the CDLQI domains of ‘self-consciousness’ (χ2 - 11.07, p-0.01), ‘hobbies’ (χ2 - 16.82, p-0.01) and ‘sports’ (χ2 - 11.79, p-0.08). Median FDLQI scores of caregivers with children having joint involvement was 19 (IQR 8–24.5) and for those without joint involvement was 9.5 (IQR 4–18); however, scores could not reach a significant difference between the two groups (p-0.32).

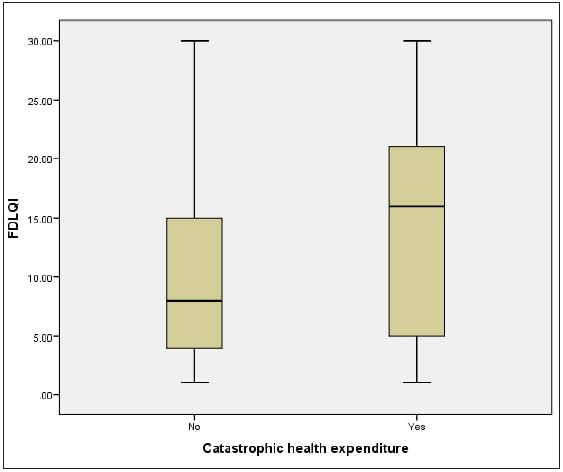

Duration of illness had a negative correlation with CDLQI (p-0.16; rs = −0.13) and FDLQI (p-0.185; rs = −0.19) scores but wasn’t found to be statistically significant. Higher treatment expenditure had a significant positive correlation with overall FDLQI score (p-0.000; rs = 0.483). Median yearly income of the caregivers was 2,40,000 rupees (2941.7USD) approximately and median yearly expenditure was 1,80,000 rupees (2206.2USD) approximately, while median yearly treatment expenditure was 18,500 rupees (226.7USD) approximately. Catastrophic health expenditure was seen in 41 (40.1%) patients and their FDLQI was significantly higher (p-0.014) in comparison to caregivers who did not experience catastrophic health expenditure [Figure 5].

Export to PPT

The median distribution of CDLQI was not significantly different among children with the involvement of exposed and non-exposed body sites. However, median distribution of FDLQI was significantly higher in caregivers whose children had involvement of exposed body sites (p-0.003). Higher FDLQI scores were noted in caregivers of children who received systemic drugs compared to those who received only topical treatment (p-0.008). However no significant difference in FDLQI was noted among different oral drugs. Response to treatment had a negative correlation with FDLQI (p-0.001; rs = −0.333); however, this did not meet significance on linear regression.

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed a positive correlation of FDLQI with exposed body sites affected (p-0.003), CDLQI (p-0.000), treatment expense (p-0.031) and negative relation with duration of illness (p-0.04) [Table 3].

Table 3: Multiple linear regression analysis to estimate relationship between FDLQI and selected factors

Coefficientsa Model Unstandardised coefficients Standardised coefficients t P-value Collinearity statistics B Std. Error Beta Tolerance VIF 1 (Constant) 9.211 3.603 2.557 0.012 Patient’s age −0.224 .271 −0.098 −0.825 0.412 0.223 4.486 Patient’s gender 1.418 1.064 0.082 1.334 0.186 0.828 1.208 Duration of illness −0.433 0.210 −0.138 −2.062 0.042 0.702 1.425 Response to treatment −0.774 0.708 −0.071 −1.093 0.277 0.718 1.392 Nail involvement −0.383 1.078 −0.022 −0.355 0.724 0.788 1.268 Exposed area affected 2.977 0.956 0.180 3.116 0.003 0.846 1.182 BSA −0.040 0.076 −0.075 −0.533 0.595 0.158 6.326 PASI 0.177 0.145 0.163 1.225 0.224 0.178 5.615 CDLQI 0.616 0.087 0.619 7.092 0.000 0.415 2.408 Caregiver gender −1.385 1.581 −0.082 −0.876 0.383 0.363 2.753 Caregiver education −0.840 0.615 −0.104 −1.366 0.176 0.541 1.847 Occupation 0.104 0.516 0.019 0.201 0.841 0.367 2.727 Treatment expense 0.001 0.000 0.149 2.198 0.031 0.685 1.461 DiscussionOf the 102 patients enrolled, 85.29 % of children had impairment in the CDLQI scores due to psoriasis. As a secondary impact, 96.1% of caregivers reported impairment in FDLQI scores. The median scores of PASI, CDLQI and FDLQI were 3.4, 7 and 11, respectively. The ‘emotional distress’ was the most affected FDLQI item, followed by ‘time spent/burden of care’ and ‘physical well-being’. In the CDLQI , the item ‘symptoms’ was most affected, followed by ‘self-consciousness’ and ‘treatment’ items. The FDLQI score had a significant correlation with CDLQI and PASI. We observed that the PASI correlated well with CDLQI scores; this has also been shown by other studies.11,12

In an Australian study, similar results were observed where the median PASI was 4.2, median FDLQI was 12 and the correlation coefficient between PASI and FDLQI was 0.44 (P-0.001). However, unlike our study in which the item ‘emotional’ was most impacted with highest mean, they found ‘burden of care’ to be the most affected item with a mean value of 2.05, followed by the item ‘emotional’ having a mean value of 1.54.13

A multicentre study from Turkey observed a median CDLQI score of 6 (IQR 0–24); ‘symptoms’ and ‘feelings’ were the most severely impaired domains of the CDLQI and ‘emotions’ was the most severely impaired domain of the FDLQI.7 Likewise, Tollefson and colleagues found the item ‘emotional’ to be the most impaired among the FDLQI. These results were in consonance with our findings.4

Our study did not find a significant difference in the mean scores of CDLQI and FDLQI for male versus female children or between children ≤10 years versus >10 years.7,14 Similarly, the median FDLQI scores of mothers and fathers were not significantly different for male versus female children. However, Tekin et al. found a greater QoL impairment in caregivers of boys than in caregivers of girls proposing mothers may be more ‘attached’ and worried about their sons owing to cultural practices.7 Zychowska et al. found mothers to have a significantly higher impact on domains of emotions, people’s reactions, social life, time spent, housework and overall FDLQI scores than fathers. These findings were explained based on mothers having a higher emotional attachment with children as they are more involved during illness and daily routine care, resultantly spending extra time with them.14 Salman et al. categorised children into age groups ≤12 years and >12 years; however, similar to our study, they found no significant difference in the median PASI, duration of disease, CDLQI and FDLQI scores.15

Joint involvement significantly affected the quality of life of patients and caregivers and made children more self-conscious about the disease. The FDLQI scores of caregivers of children with joint involvement and without joint involvement were not found to be significantly different in our study, possibly due to a smaller sample size of children with joint involvement. Meneghetti et al. found the CDLQI scores to be significantly higher in children with musculoskeletal involvement and the risk of impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was eight times higher in the presence of musculoskeletal pain.16 Ganemo et al. found children with joint complaints having higher Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) scores.17

We observed higher FDLQI scores when the children received systemic drugs compared to only topical treatment. However, they were likely to have more severe disease involvement as reported by others too.13 Treatment expense was found to have a significant linear correlation with FDLQI scores. Considering India is a low-income country with an under-penetration of insurance, most of the treatment expenditure is out-of-pocket. Hence, unlike other studies, we performed a cost analysis and found that 40% of the households experienced catastrophic health expenditure. The FDLQI correlation with treatment expense was stronger with caregivers experiencing catastrophic health expenditure. Psoriasis treatment imposes a significant financial burden on the families of the patients; however, chronic skin diseases such as psoriasis are not given due importance in India’s national health care policies. In order to reduce the economic burden related to health expenditure, treatment may require government support under community-based health insurance schemes to improve standard of care as well as the quality of life of patients and caregivers.18,19

The involvement of visible body sites can affect social life and inflict psychological morbidity in children and caregivers.20 Significantly higher FDLQI scores were observed in caregivers whose children had involvement of exposed body sites in comparison to children only with involvement of unexposed sites. However, CDLQI was not significantly different between the two groups.20 Tekin et al. found a higher CDLQI score in patients with scalp involvement than those without scalp involvement, but not statistically significant (P-0.138). Scalp involvement leads to difficulty in combing and easy visibility of scales over the clothes, impacting the psychosocial well-being of a child.7

There is a higher prevalence of stigma, anxiety and depression among caregivers of patients with psoriasis.5,21 CDLQI and FDLQI indirectly assess the severity of the patient’s disease and may help in the early identification of the mental status of the patient and caregiver. Hence, early evaluation of children’s quality of life may help provide better treatment and psychological support for the children and the caregivers.22

LimitationThis study had a small sample size and psychological morbidity was not assessed.

ConclusionPsoriasis has a deleterious effect on the psycho-social aspects of quality of life of children and their caregivers. The items ‘emotional’ followed by ‘burden of care’ were the most impacted and most affected among Family Dermatology Life Quality Index. Education and counselling about the disease may help in improving the quality of life of patients and caregivers.

留言 (0)