A man in his sixties presented with a mildly pruritic, annular-looking petechial rash that first appeared on his lower limbs 2 years ago. The rash progressed upwards to his anterior trunk and cheeks. He had Parkinson’s disease and was started on co-formulated levodopa and benserazide, a few months before the rash appeared. He had no systemic symptoms, anorexia, or weight loss. His other medications include ropinirole and selegiline, both of which were started a year before rash onset.

Examination revealed extensive annular-looking petechial macules involving the lateral cheeks, neck, trunk, and both upper and lower limbs [Figures 1a and 1b]. His back and buttocks were spared. Punch biopsies of the macules on both the patient’s neck and abdomen showed superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates admixed with plasma cells, scattered eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells [Figure 1c]. A few haemosiderin pigments were also identified on Perl’s stain. No dysplasia or epidermotropism of lymphocytes was seen.

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

AnswerDiagnosis: Purpura annularis telangiectoides of Majocchi

DiscussionPurpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM), also known as Majocchi’s disease, is a subtype of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPD), a group of histopathologically similar capillaritis that differs by their clinical morphology. Our case illustrates a patient with an annular-looking petechial eruption but with atypical features of extensive involvement of the trunk and face after the initiation of co-formulated levodopa and benserazide. Given the temporal relationship and the presence of eosinophils, a drug reaction could be a possibility. This patient had a platelet count of 294 × 109/L.

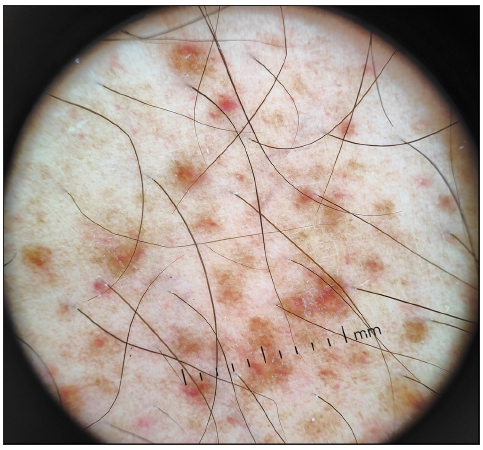

PATM, first described in 1896, is an uncommon condition that tends to affect children and young females.1 It presents as bluish-to-red macules with dark-red telangiectatic spots and the centrifugal extension of these macules gives it its characteristic annular configuration. Dermoscopy shows irregular round-to-oval red dots, globules, and structureless areas with diffuse ill-defined brownish-red homogenous areas [Figure 1d]. Like most PPDs, PATM predominantly involves the lower limbs with extension to the upper extremities symmetrically, although an atypical unilateral presentation of PATM has been reported.2 Extensive involvement including the trunk and face, as in this case, has not been reported.

Export to PPT

PATM shares similar histopathology features with the other PPD subtypes: dilated blood vessels, erythrocyte extravasation, haemosiderin deposition, and perivascular lymphohistiocystic infiltration. In a retrospective review by Huang et al., all inflammatory reaction patterns (lichenoid, perivascular, interface, spongiotic, granulomatous) can be seen in PPD but only lichenoid and perivascular patterns were found in PATM.3

The pathogenesis of PATM and other PPD remains unknown, although venous hypertension, gravity, capillary fragility, and focal infections have been proposed as contributing factors. Drug associations with analgesics, oral hypoglycaemic agents, and anti-hypertensive agents have been reported, in particular with Schamberg disease.4 While neuroactive agents (e.g. carbromal, chlordiazepoxide, lorazepam, meprobamate) have been reported, drugs used for Parkinson’s disease, as in this case, have not been previously associated.

PATM should be differentiated from other causes of petechiae such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis with annular morphology, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, PPD-like mycosis fungoides, and purpuric pityriasis rosea [Table 1]. There are also reports that PPD may mimic or progress to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).1,5 In 56 patients with persistent PPD, Toro et al. found 29 patients (52%) with histological features of CTCL.5 Hence, histological diagnosis should always be pursued in patients with atypical or persistent presentations of PPD.

Table 1: Distinguishing features between selected conditions

Feature Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with annular morphology PPD-like mycosis fungoides Pityriasis Rosea Age 5th decade 3rd to 4th decade All ages After 50 years of age 2nd to 3rd decade Gender predilection Male Female None Male None Location Lower limbs Lower limbs Lower limbs Lower limbs (but usually more widespread)Trunk with a herald patch

Proximal limbs (Langer’s lines)

Pruritus None to mild None to mild None to mild Yes Yes Palpable lesions No No Yes No Yes (Papulosquamous) Other bleeding manifestations No Yes (other mucocutaneous sites) No No No Associations Venous insufficiency, exercise, RA, SLE, CLL, hyperlipidaemia, drugs (NSAID, statins, CCB, ACEi, beta-blockers) Infections (HIV, hepatitis C, CMV, VZV), drugs, SLE, APS, HIV, CVID Infections (Streptococcus pyogenes, bacterial endocarditis, HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis), malignancy (paraneoplastic), drugs (antibiotics, thiazides, phenytoin, allopurinol, warfarin, NSAID), autoimmune (SLE, dermatomyositis, RA) Progression from PPD Infections (HHV-6, HHV-7), medications (vaccines, gold, captopril, barbiturates, penicillamine, clonidine) Histology Small vessel perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation with endothelial cell swelling, no leukocytoclasis, extravasated red blood cells (RBC) with variable haemosiderin deposition in macrophages Erythrocyte extravasation in the absence of vascular inflammation Perivascular neutrophils with fibrinoid necrosis, some extravasated RBC, leukocytoclasis Epidermotropism with infiltration by atypical lymphocytes Subacute spongiotic dermatitis with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, focal extravasation of RBC without leukocytoclasisWhile PATM is a benign condition, the absence of guidelines and the persistent nature of this condition make management challenging. Conservative or non-pharmacological management (leg elevation, compression stockings) can be considered for asymptomatic patients.1 Suspected culprit drugs should be stopped where feasible. For symptomatic patients with PPD, treatment options include topical agents, such as corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. Other treatment options have been described with variable success, including intralesional triamcinolone, oral agents (rutoside, ascorbic acid, pentoxifylline, venoactive agents, e.g., diosmin, calcium dobesilate, colchicine, griseofulvin, cyclosporine, methotrexate), phototherapy (narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy) and laser therapy.1,4

留言 (0)