Adjustment disorder (AD) is defined as a reaction by an individual to a perceived stressor that is more intense or prolonged than what would typically be expected, given the nature of the stressor and the cultural context in which the person lives. This reaction not only exceeds the boundaries of what is considered a normal response within their cultural norms but also significantly interferes with their ability to function in daily life (1, 2). It is self-limiting as disorder is closely linked to a specific stressor or life event, and as the situation changes -whether because the stressor ends, or the individual develops coping mechanisms to handle it- the symptoms diminish or disappear (3). And the diagnosis of AD requires that the symptoms do not meet the diagnostic criteria for other mental disorders, such as a major depressive episode (MDE) (4). AD is of particular clinical interest as the risk of suicide in individuals with this diagnosis is 12 times higher than in the general population (5), and between 5% and 36% of those who have committed suicide were found to have AD through psychological autopsy (6–10). Furthermore, it involves work absenteeism and medical disabilities (11), generating significant costs, especially because AD primarily affects individuals in economically productive ages (12, 13).

Medically ill patients frequently present with AD. In high-complexity general hospitals, the proportion of patients hospitalized for medical illnesses who are evaluated by liaison psychiatrists and diagnosed with AD varies between 10.6% and 18.5% (14). In some clinical settings, the prevalence is notably high, particularly among patients facing significant medical illnesses such as cancer (with a prevalence of 23.5% and 38.6%) (15, 16), pulmonary arterial hypertension (38.2%) (17), cardiac disease (33%) (18), and infertility (60.1%) (19). It has also been found that AD leads to greater consumption of healthcare resources in this population and is associated with the development of complications (20).

A medical illness can be considered a stressful event because from the onset of symptoms, through diagnosis and treatment, emotional reactions can arise that cause suffering and impair functionality. Such reactions are considered abnormal and may be part of a range of diagnostic possibilities, including AD (21). Depressive symptoms, for instance, have a high prevalence in medical illnesses, particularly those affecting the gastrointestinal, hematological, renal, neurological, and cardiovascular systems (22), making them one of the main reasons for consultation in liaison psychiatry services.

From a clinical standpoint, diagnosing adjustment disorder (AD) in medically ill patients can be challenging and may be presented differently. Besides being a reaction to the illness and its consequences, mental symptoms can also be part of the underlying disease or an adverse effect of treatment (23). Additionally, an accurate diagnosis could guide different treatment approaches: in AD, psychotherapy aimed at coping with the stressor would be prioritized, whereas in MDE, treatment might focus on antidepressants (24, 25), which carry a higher risk of drug interactions and adverse effects in this population (26).

There are two instruments for measuring AD. One is the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire (IADQ), which has not been validated in medically ill patients (27). The other is the Adjustment Disorder New Module (ADNM), based on DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria, and validated in this population. However, this scale excludes behaviors specific to disease management, focusing only on repetitive thoughts, avoidance, and maladaptation to stressors, with the latter defined as sleep and concentration disturbances (28). Medically ill patients might show difficulties in adapting to a stressful situation through neglecting their medical treatment, losing interest in continuing recommended therapy, or neglecting self-care activities (16), rather than just sleep and concentration disturbances.

Considering these characteristics of the instruments and the current definitions of diagnostic manuals, there is a clear need to improve the definition of AD for medically ill patients and to develop an instrument for its measurement. The objective of this study was to develop and validate a measurement instrument for the evaluation and diagnosis of AD in medically ill patients.

MethodsScale development and validation study conducted in three phases (29) following the COSMIN taxonomy (30). The study was carried out in two high-complexity hospitals in Medellín, Colombia. It complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and Colombian research standards and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Antioquia (Approval Act 008, May 2020) and the participating institutions. Each patient included in the study participated voluntarily and signed informed consent.

Phase 1: item developmentA Scale Development Group (SDG) was formed to create a measurement instrument for the evaluation and diagnosis of AD in medically ill patients, whether hospitalized or treated on an outpatient basis. The SDG included a psychiatrist specializing in liaison psychiatry, two epidemiologist psychiatrists with experience in psychometrics, a psychologist with a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, and a psychologist specialized in psychometrics. To enrich the discussions, we also included a female patient with chronic kidney disease who has participated in psychology research as a patient representative. The SDG held regular meetings, and the methodology was based on individual responses to questions before each session, followed by group discussions to share and analyze individual responses and reach a consensus (31). For the theoretical definition of the construct and items, results from two qualitative studies were used (32). One phenomenological study described the differential clinical characteristics of AD (33) and another grounded theory study explored the diagnostic criteria used by psychiatrists and psychologists for AD (34). With this input, the operational definition of AD and its conceptual domains were developed (35).

Based on this operational definition, in-depth interviews were conducted with seven adult patients with medical illnesses hospitalized in the two participating hospitals. These interviews provided empirical input for the construction of items from the target population (36). An interview guide was used, delving into how to ask about the conceptual domains of AD and the process of adapting to a medical illness. A psychiatrist epidemiologist trained in qualitative research conducted the interviews, which were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then analyzed using grounded theory techniques to identify potential items in the words and expressions used by the patients, ensuring content validity of the items from their inception. The item pool was evaluated by the SDG in an iterative process to determine relevance, domain comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility. This step resulted in the first version of the scale.

Phase 2: scale developmentThe first version of the scale underwent a content validity evaluation process with patients (37). Cognitive interviews were conducted to determine the patient’s understanding of each item, difficulties in responding, and any deviation from the construct while reasoning or responding (38). Initially, seven Colombian adult medically ill patients, both hospitalized and from outpatient settings, were included. Each item was presented to them with the instruction to “think aloud” to make their reasoning explicit while responding (39). Verbal probes were also used to assess the comprehensibility and exhaustiveness of the items, the acceptability of the questions, and the absence of discrimination. Memos were taken to note observable behaviors during their responses (40).

The cognitive interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed line by line independently by two psychiatrists, who later met to discuss the comprehensibility evidenced. As a result, it was necessary to modify the phrasing of some items, which then had to be re-evaluated by a new group of seven patients through an iterative process of cognitive interviews and subsequent item revisions or eliminations due to lack of comprehensibility or relevance. Five rounds of cognitive interviews, each with seven patients, were required.

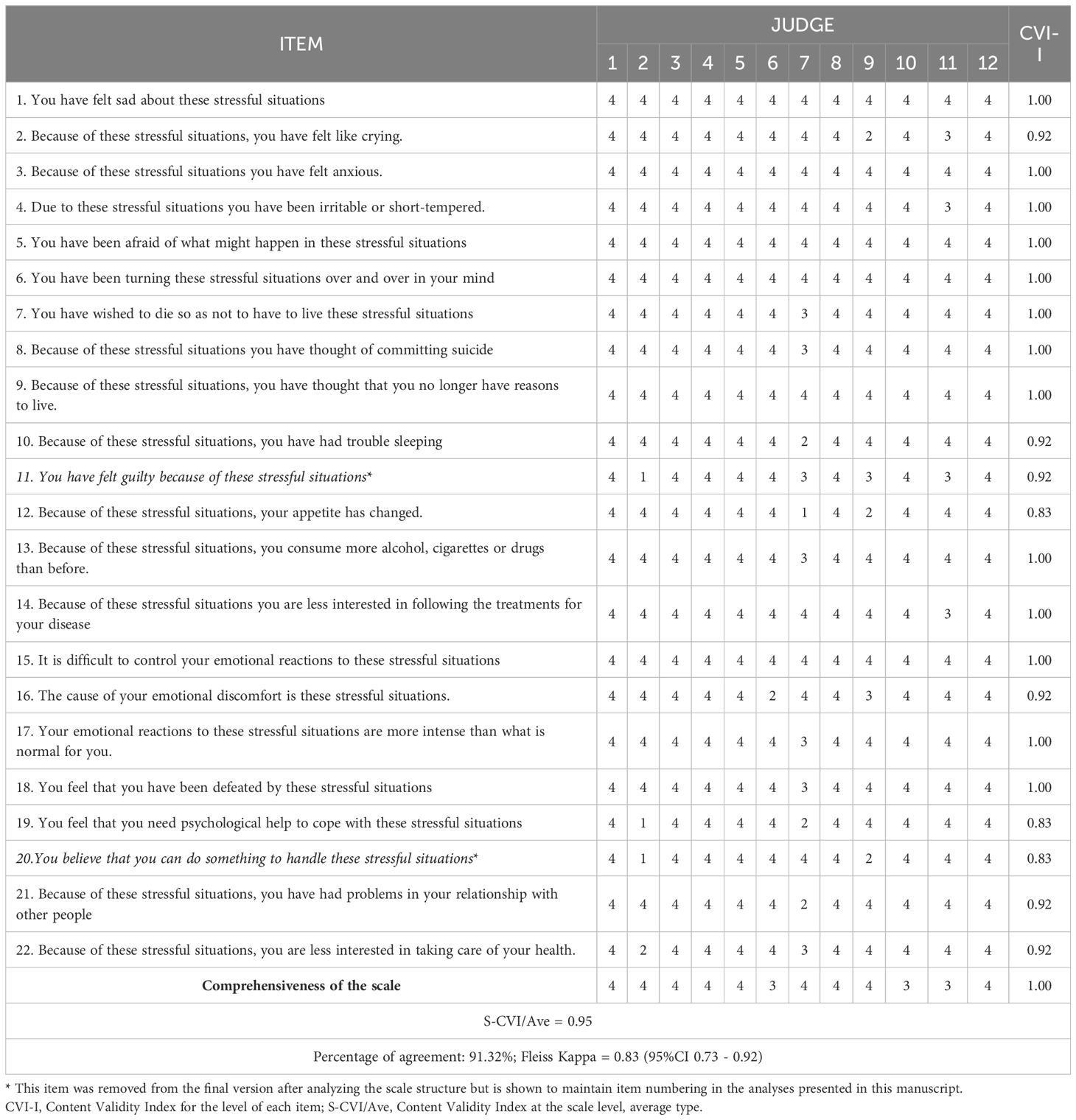

After the content evaluation by patients, the preliminary version of the scale was subjected to expert clinical review. This included 12 psychiatrists and psychologists experienced in evaluating medically ill patients, who assessed the relevance of each item for measuring the construct of AD and the comprehensiveness of the version. Each item was rated on a scale from 1 to 4 (1 = Not relevant, 2 = Slightly relevant, 3 = Relevant, 4 = Very relevant), and then dichotomized as either not relevant (values 1 and 2) or relevant (values 3 and 4) (41). The content validity index at the item level (CVI-I) was calculated and deemed adequate if it was greater than 0.78 (42).

Additionally, the scale-level average content validity index (S-CVI-Ave) was calculated, with values greater than 0.80 considered adequate (43), and Fleiss’ Kappa (κ) was used as a measure of agreement. Only after this evaluation did the SDG approve the final version of the instrument. A pilot test was then conducted with 20 medically ill adult patients to monitor the completion process, determine the average completion time, and identify missing data. The data from participants in the pilot test were included in the psychometric property evaluation.

Phase 3: evaluation of psychometric propertiesParticipantsThe inclusion criteria were: Colombian adults with a confirmed medical diagnosis, from any educational background, who were receiving outpatient or inpatient care at one of the two participating centers (excluding Intensive Care Unit and Special Care Unit), and those who agreed to participate after the informed consent process. Exclusion criteria were patients with a diagnosis of delirium, dementia syndrome, active psychosis or mania, intellectual disability, or language impairments that prevented effective communication.

A sample size was calculated for the evaluation of each psychometric property. For structural validity, the goal was to recruit at least 500 subjects, which is the recommended sample size for conducting factor analyses (44). Internal consistency was also assessed within this subsample. For item response theory (IRT) analysis, 500 participants were included as recommended by Ayala (45). Test-retest reliability was evaluated in 41 subjects, based on the sample size estimation formula described by de Vet (46), assuming an expected intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.70, with a precision level of 0.20, type I error of 0.05, and type II error of 0.20.), For criterion validity, it was estimated that 204 subjects were needed to achieve an area under the ROC curve (AUROC) of 0.70, with a confidence interval width of 0.20, an expected AD prevalence of 18.5% in general hospitals (47) and a 95% confidence level (48). For convergent construct validity, a subsample of 65 subjects was calculated to seek moderate correlations with similar instruments, according to the formula for a Spearman’s correlation coefficient >0.50 in the alternative hypothesis and <0.10 in the null hypothesis (49).

ProceduresThe scale was administered by trained physicians and nursing assistants. The scale was self-administered by the patient or, in cases where manipulating paper and pencil was difficult due to the presence of catheters or medical reasons, assisted administration was performed. For test-retest reliability, the same evaluator reapplied the scale to a subsample of participants three to four days after the initial application. This time frame was considered appropriate given the high variability of the construct and to prevent recall of the questions. The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (50), completed by both the patient and the initial evaluator, was used as an anchor to ensure that patients remained stable during the interim period for the analysis of this property, given that AD can be fluctuating.

For criterion validity, the reference standard was an independent evaluation by a liaison psychiatrist conducted at the same hour the instrument was administered. The psychiatrist independently assessed the patient using a symptom checklist derived from the operational definition of the SDG. It was considered necessary to use the theoretical model developed in order to be consistent with the change in the definition of AD by placing it in the same hierarchy, as opposed to other diagnostic criteria or structured interviews. For convergent construct validity, the calculated subsample was administered the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (51) and the 8-item Adjustment Disorder New Module (ADNM-8) (52). For discriminant construct validity, the scores of patients diagnosed with AD were compared to those without AD.

InstrumentsHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)This is a 14-item self-report scale with three response options, designed to describe depressive and anxious symptoms experienced over the past week (51). It is one of the most commonly used tools for detecting emotional distress in individuals with physical illnesses (53). In Colombia, it has been validated in oncology patients, showing a structure consistent with separate anxiety and depression factors, and demonstrating adequate reliability and validity as a screening tool for anxiety and depression. Internal consistency has been measured with Cronbach’s alpha and was adequate for the anxiety (α=0.80 to 0.86) and depression (α=0.80 to 0.87) subscales (50).

New Adjustment Disorder Module (ADNM)This is a self-report scale that originally includes 29 items (54). It begins with a list of stressful events potentially triggering adjustment disorder, where respondents select those experienced in the past year to reference for the rest of the scale. The 8-item version (ADNM-8) assesses adjustment disorder symptoms over the past two weeks, categorized into two dimensions: preoccupation (cognitive rumination) and failure to adapt (issues with sleep, concentration, and functionality). It shows evidence of adequate reliability and validity. Specifically, the internal consistency reliability of the ADNM-8 measured with the Cronbach alpha for the total ADNM-8 scale was high (α=0.83) and also for the preoccupation (α=0.85), and the failure to adapt (α=0.7) subscales (52).

Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI)This is a Spanish-validated scale that qualitatively describes the severity of the condition and the change observed in the patient compared to the baseline state (50). The subscale evaluating improvement due to treatment was used to ensure construct stability. Improvement is defined as the distance between the patient’s current condition and the condition recorded at the beginning of treatment. This subscale item was completed by both the patient and the evaluator who administered the scale during the initial assessment.

Statistical analysisThe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were described using descriptive statistics. For quantitative variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were presented if they had a normal distribution; otherwise, the median and interquartile range were used. Qualitative variables were reported using absolute and relative frequencies. For the description of stress events, a quantitative analysis of textual data was conducted with natural language processing to calculate the frequency of words written by the patients. The frequency of response options for each item, missing values, and the presence of floor and ceiling effects (defined as values exceeding 15%) were also assessed (46). Missing values in the items were imputed using the mean (simple imputation) due to their low frequency (55).

For structural validity, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was conducted to assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, with values considered acceptable if greater than 0.70 (56). Next, the number of dimensions was examined using Horn’s parallel analysis, which contrasts observed eigenvalues with expected eigenvalues through resampling techniques (57). Based on the suggested number of factors, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using principal axis factoring with a polychoric correlation matrix and oblique rotation to accommodate potentially correlated dimensions. Principal axis factoring represents observed correlations through a latent variable, is unaffected by violations of normality assumptions, and is robust to unequal factor loadings or few items per factor (58). Factor loadings were evaluated. Additionally, McDonald’s omega, with its corresponding confidence interval (CI95%), and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated for each identified dimension to assess internal consistency.

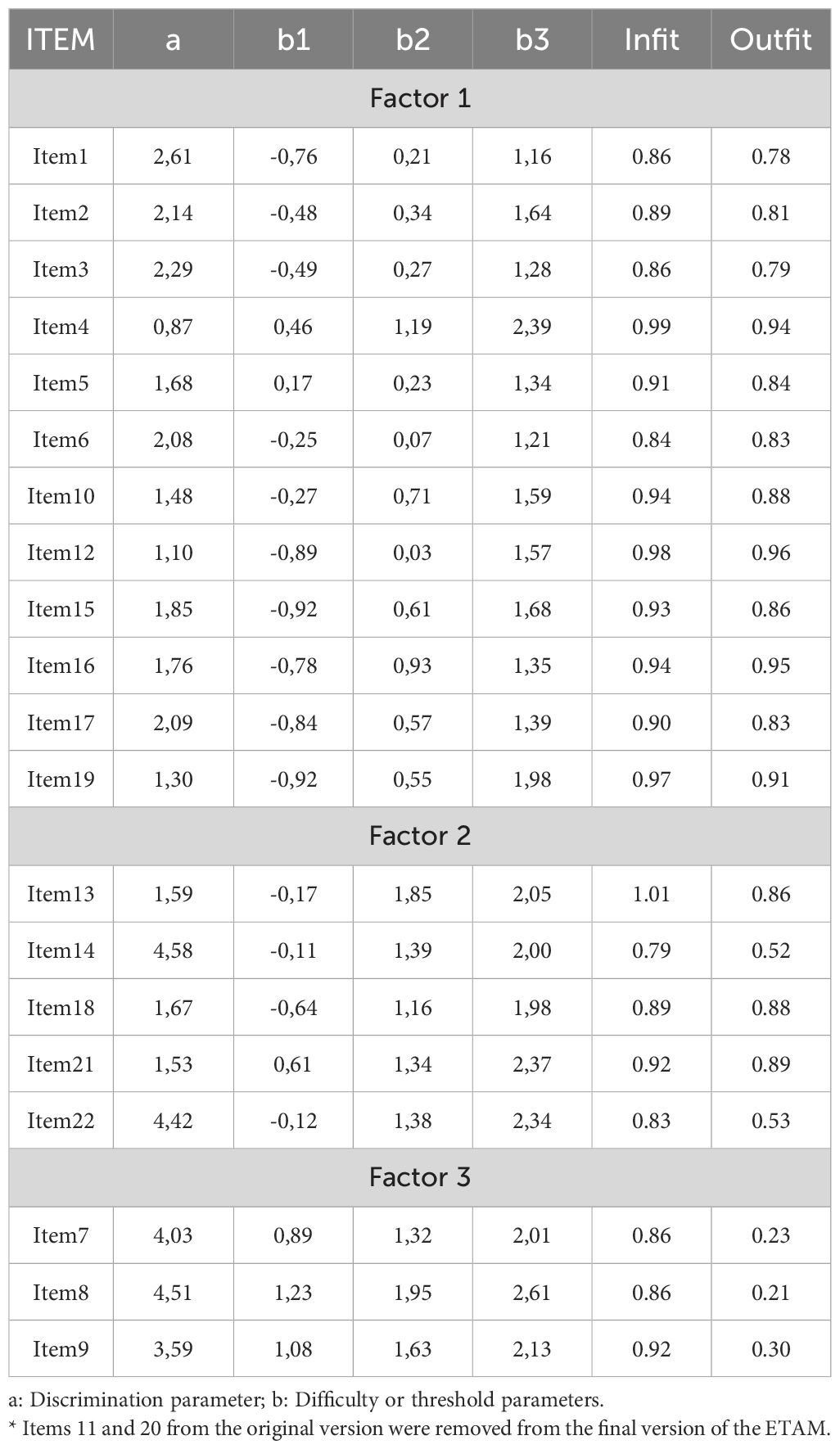

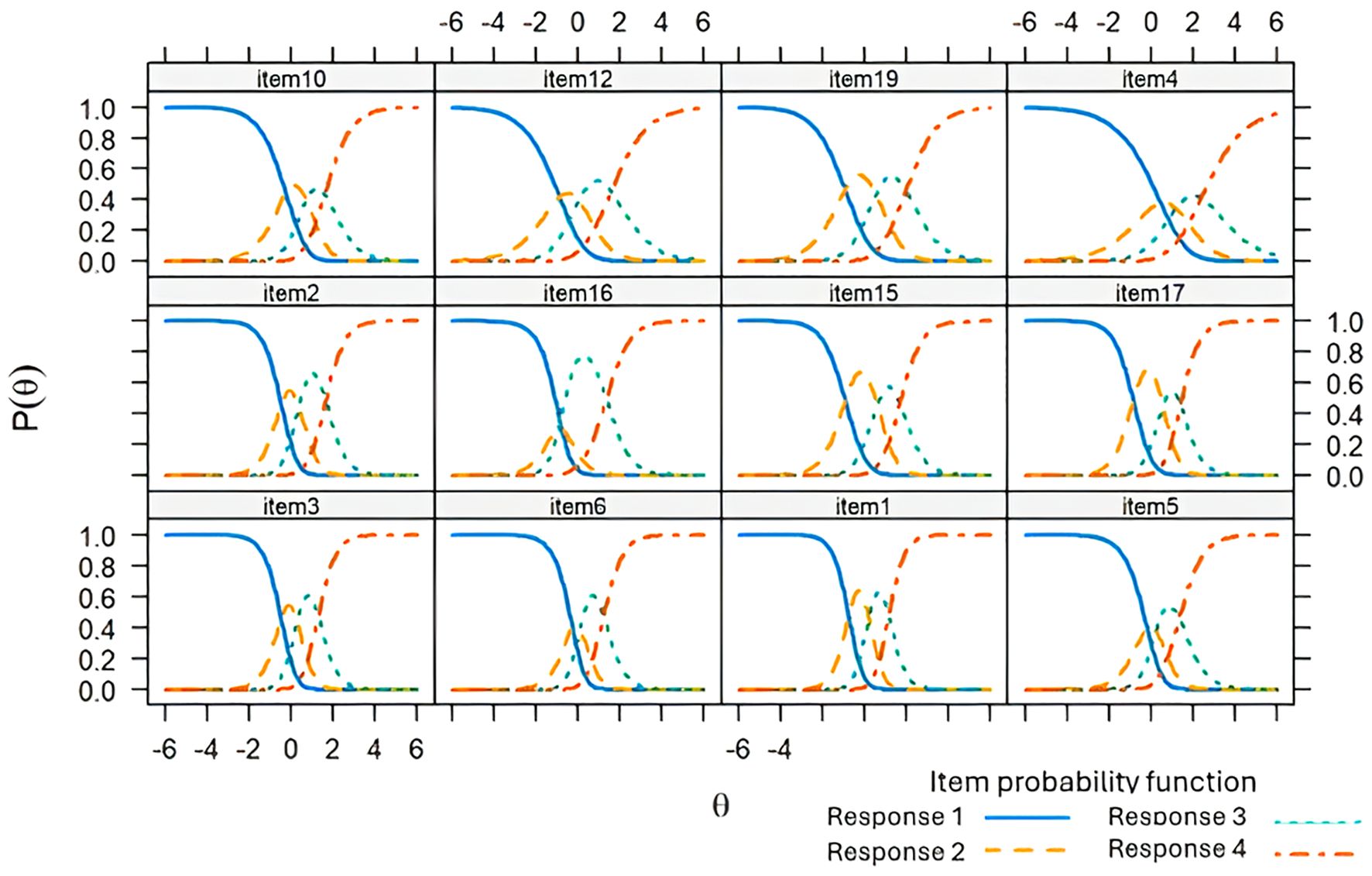

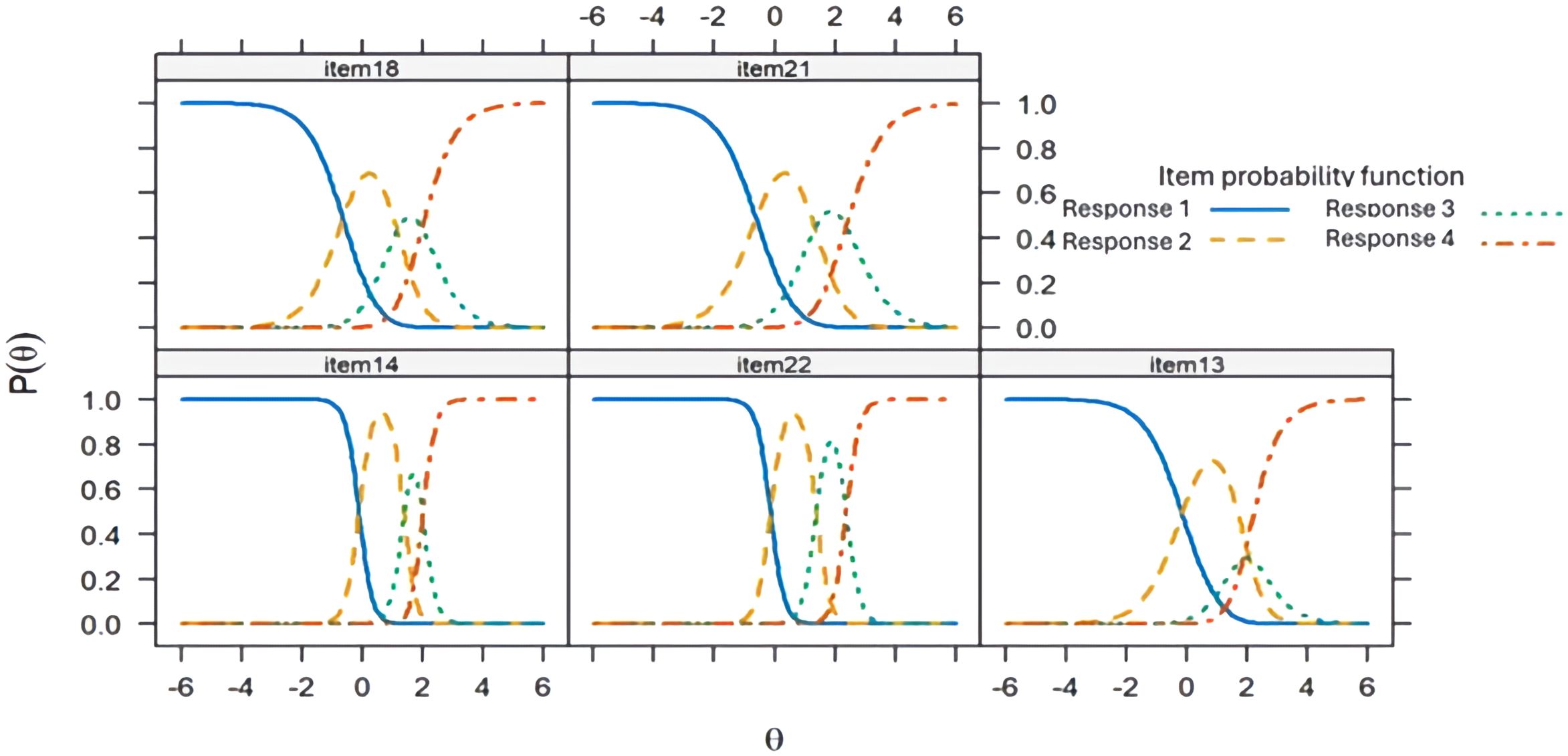

The discrimination (a) and difficulty (b) parameters were also analyzed using Item Response Theory (IRT). Parameters were estimated using a generalized partial credit model for polytomous items (45) applied to each dimension according to the solution derived from factor analysis to ensure the assumption of unidimensionality (50). The a parameter, also known as the slope, measures the strength of the relationship between the item and the latent variable (in this case, the AD); the b parameter, or threshold parameters, represent the points along the latent variable where the item response categories are most informative (59). The fit was evaluated for each item based on the values of the infit and outfit statistics, which were considered adequate with values >0.4 and <1.6 (29). Additionally, category response curves (CRC) were constructed for each item.

Test-retest reliability was assessed using the ICC for absolute agreement (95% CI) for the entire scale and each dimension, with a value of ≥0.70 considered adequate (46). For concurrent criterion validity, the dichotomous diagnosis of AD as determined by the independent liaison psychiatrist was used as the reference standard. To consider the present AD, all the symptoms on the checklist should be verified. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was calculated, and based on this curve, a cutoff point was established to compute sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and likelihood ratios.

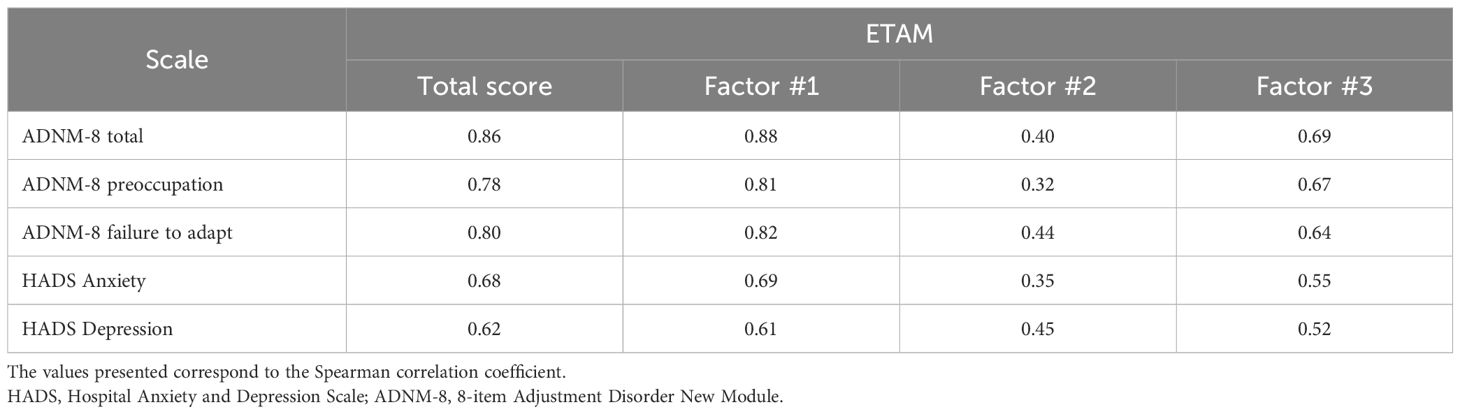

Evidence of convergent construct validity was obtained by calculating Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for scores obtained on the HADS and the ADNM-8. A priori, it was hypothesized that moderate to strong positive correlations (60), with correlation coefficients greater than 0.60 would be found, as these measures assess related constructs. It was also hypothesized that patients diagnosed with AD would score higher on the ETAM compared to those without AD, with significant differences and a moderate effect size, as determined by calculating Hedges’ g for the mean differences between two independent samples (61). Although the instruments were previously validated, we also measured the internal consistency of the HADS and the ADNM-8 scales with Cronbach’s alpha to ensure that their reliability is maintained in our sample.

Data were recorded in REDCap (62), and statistical analysis was conducted using R software (63) and R Studio (64), with the packages: ‘psych’ (and its functions for factor and reliability analysis) (65), ‘quanteda’ (66), MBESS (67), and ‘ltm’ (for IRT modeling) (68).

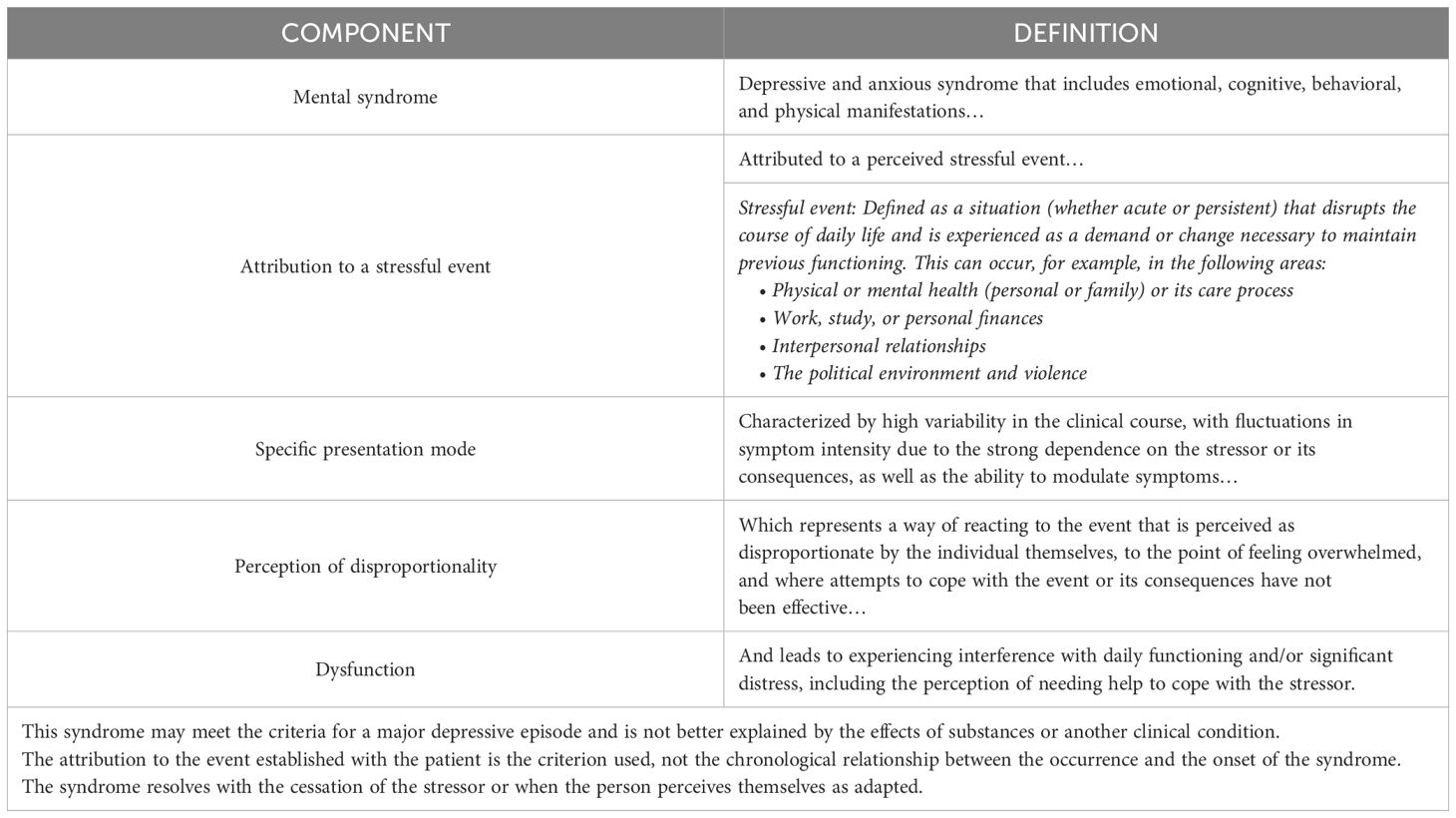

ResultsItems and scale developmentThe operational definition proposed by the SDG centers on the presence of a depressive or anxious syndrome attributed to a stressful event, which generates dysfunction and is considered by the patient as disproportionate (Table 1). In alignment with this, the conceptual domains were: 1) depressive and anxious symptoms related to the medical condition; 2) attribution to stressful events; 3) perception of disproportion; and 4) dysfunctionality. This syndrome may meet the criteria for a major depressive episode, as it was considered to be in the same hierarchy and not merely a diagnosis of exclusion, and it is not better explained by substance effects or another clinical condition. Using qualitative research, SDG meetings, and in-depth interviews, a pool of 64 self-report items was created, of which 31 items were approved by the SDG to form the first version of the scale.

Table 1. Operational definition of adjustment disorder developed by the Scale Development Group.

Five rounds of cognitive interviews, each with seven patients (n=35), were necessary. These patients were men (n=18; 51.4%) and women (n=17; 48.6%) ranging in age from 42 to 58 years, with diseases of medical (n=21; 60.0%) and surgical (n=14; 40.0%) origin. During the cognitive interviews, it was observed that having a predefined list of stressful situations categorized by themes (health, economy, social relationships, political and social situation) made it difficult for patients to classify their stressful situation or led them to seek situations related to the theme, even if they were not stressful. As a result, it was decided to allow patients to freely describe the situation they were experiencing rather than providing predefined options, as the conceptual emphasis is on their reaction to these situations.

Following this process, a preliminary version of the scale with 22 items was developed, which showed adequate content validity indices, with high agreement among evaluators (Table 2). Thus, the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM, from the Spanish “Escala del Trastorno de Adaptación en pacientes Médicamente enfermos”) was finalized and approved by the SDG. Conceptually, the scale addresses the free description of perceived stressful situations that occurred in the past 15 days and then asks about affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physical symptoms, which are assessed on how frequently (1=Never, 2=Rarely, 3=Frequently, 4=Always) the subject has experienced them in the past 15 days.

Table 2. Content validity assessment of the 22 initial items of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) by 12 experts.

The scale also assesses the attribution of symptoms to stressful events, the disproportion of the reaction, and perceived dysfunction through Likert-type questions (1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Agree, and 4=Strongly Agree). The item scores were conceived as the raw sum of responses, with a minimum score of 20 and a maximum score of 80. In the pilot test conducted (n=20), no missing items were found, no difficulties with administration were reported, and the average time to complete the scale was 7 minutes and 15 seconds (median of 6 minutes and 22 seconds).

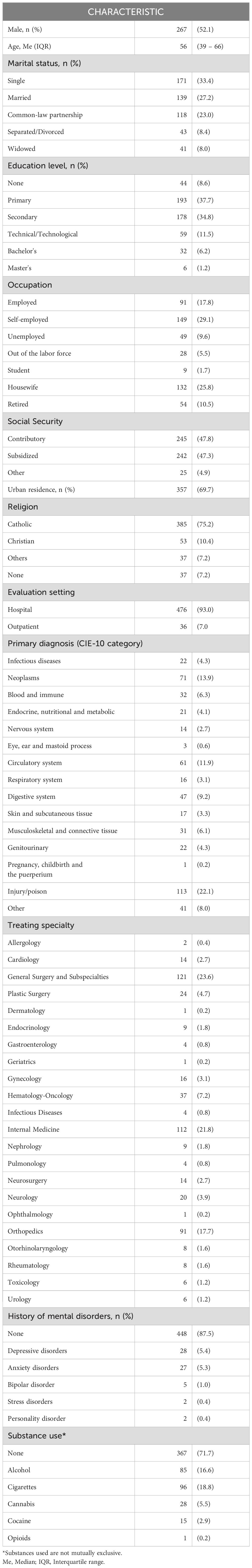

Participants and their responsesA total of 512 patients were included in the validation phase of the study. The participants were primarily in their fourth and sixth decades of life, with educational backgrounds ranging from primary to secondary schooling. The majority resided in urban areas, were of Catholic faith, and represented both public and private health insurance schemes. The majority were evaluated during hospitalization for various medical conditions, with internal medicine and general surgery, including their sub-specialties, being the most frequently treating specialties (Table 3). 87.5% of participants had no history of mental disorders, and 71.7% had no history of substance use.

Table 3. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients assessed with the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) (n=512).

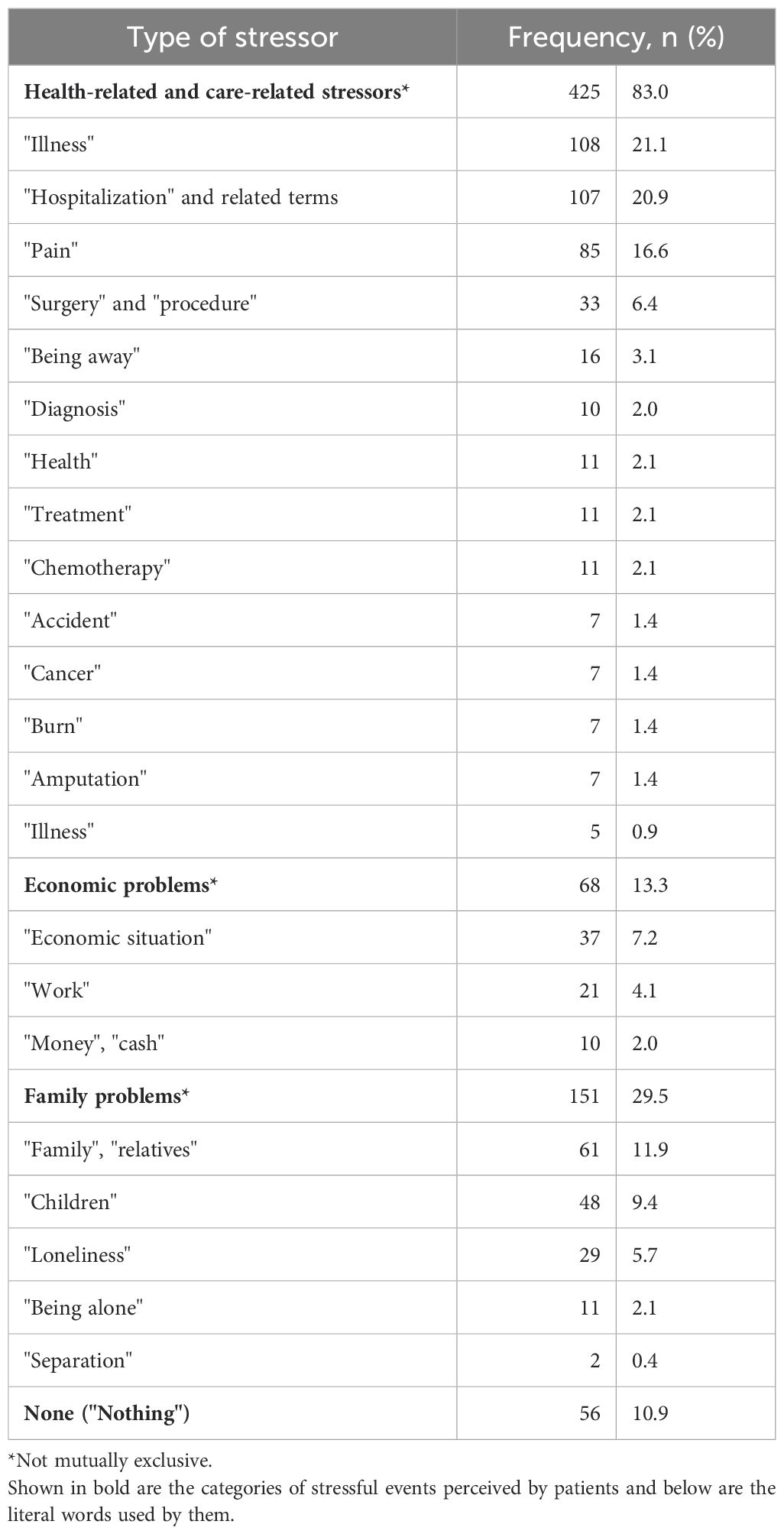

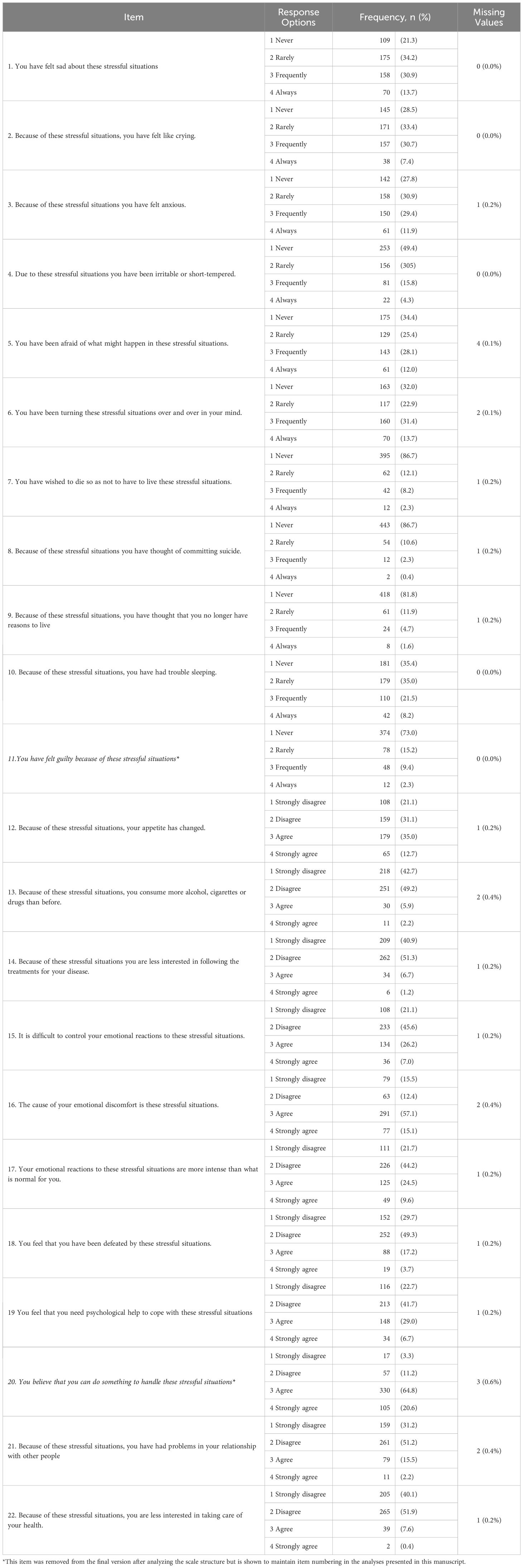

Regarding the stressors reported by patients, health-related issues were the most frequent, but economic and family problems were also mentioned, and 10.9% did not report any stressors (Table 4). The frequency of responses (Table 5) shows missing values of less than 0.4% and a floor effect indicated by over 80% of responses being “Never” for items 7 (“You have wished to die so as not to have to live these stressful situations?”), 8 (“Because of these stressful situations you have thought of committing suicide”), and 9 (“Because of these stressful situations, you have thought that you no longer have reasons to live”). Given their importance, these items were included in the final version.

Table 4. Perceived stressful events and words used by patients assessed with the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) (n=512).

Table 5. Frequency of responses to the 22 initial items of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) (n=512).

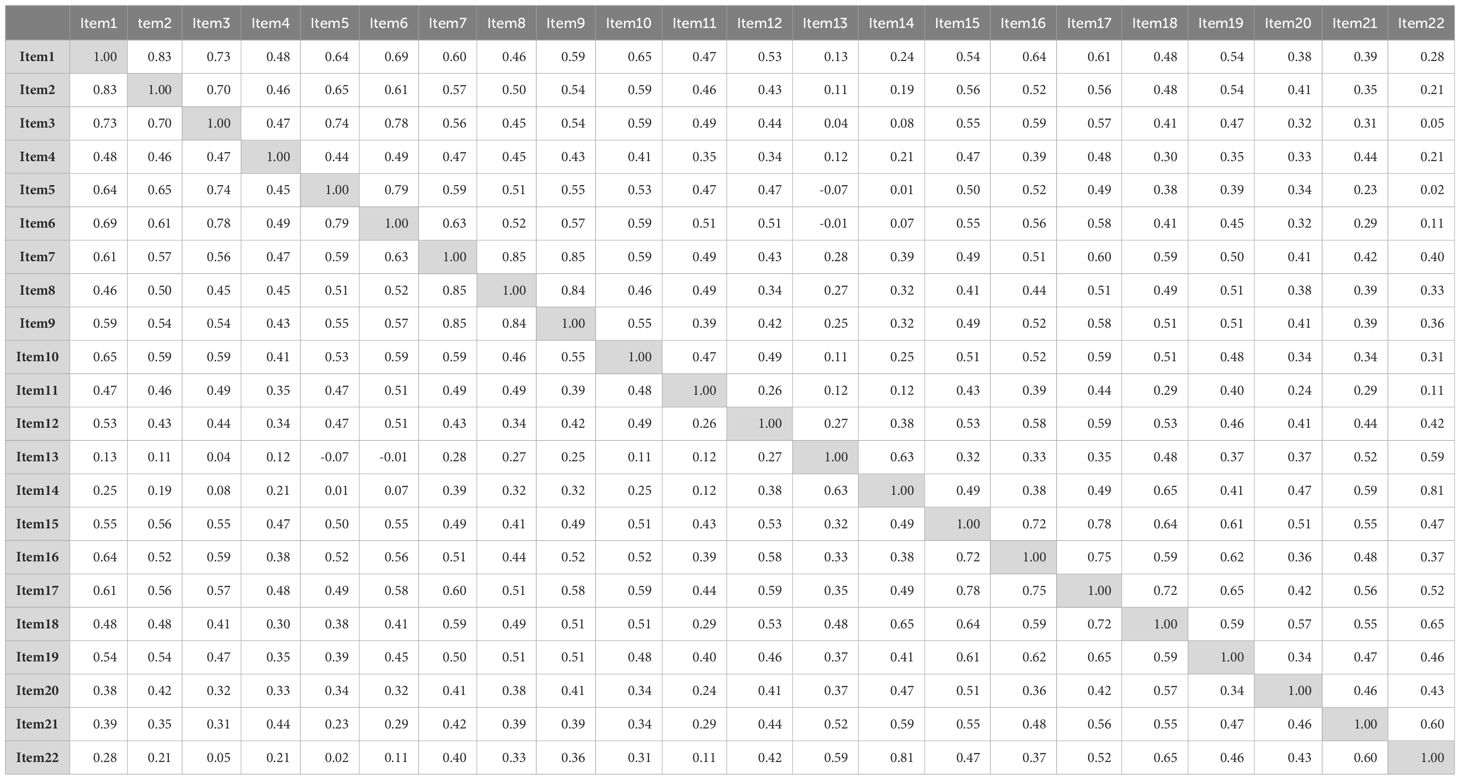

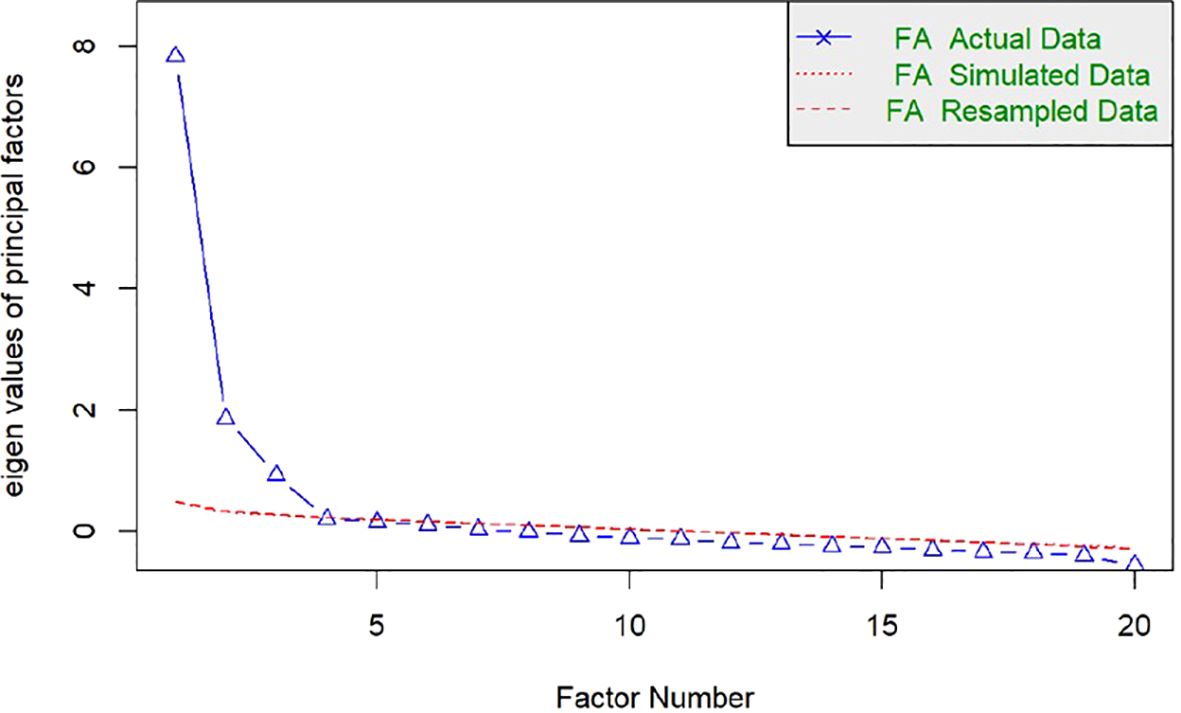

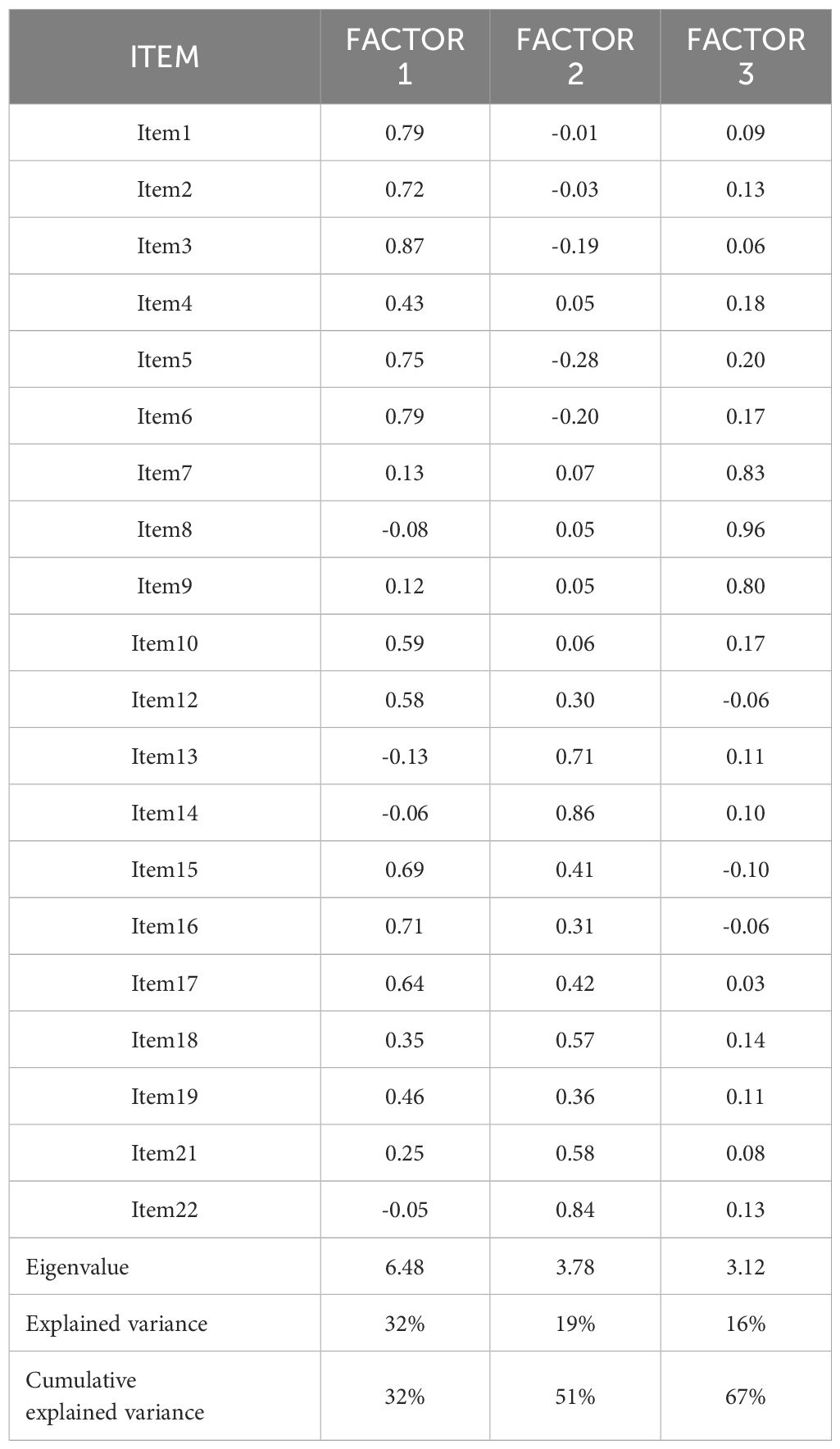

Scale structureThe Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.93. Using a polychoric correlation matrix, correlations ranged from -0.07 to 0.83, suggesting a multidimensional structure (Table 6). The Horn’s parallel analysis indicates a three-factor structure (Figure 1). In the initial Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation, a three-factor structure was found explaining 67% of the variance.

Table 6. Polychoric correlation matrix of the 22 items of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM).

Figure 1. Sedimentation plot from Horn's parallel analysis. The parallel analysis suggests that the number of factors is equal to 3.

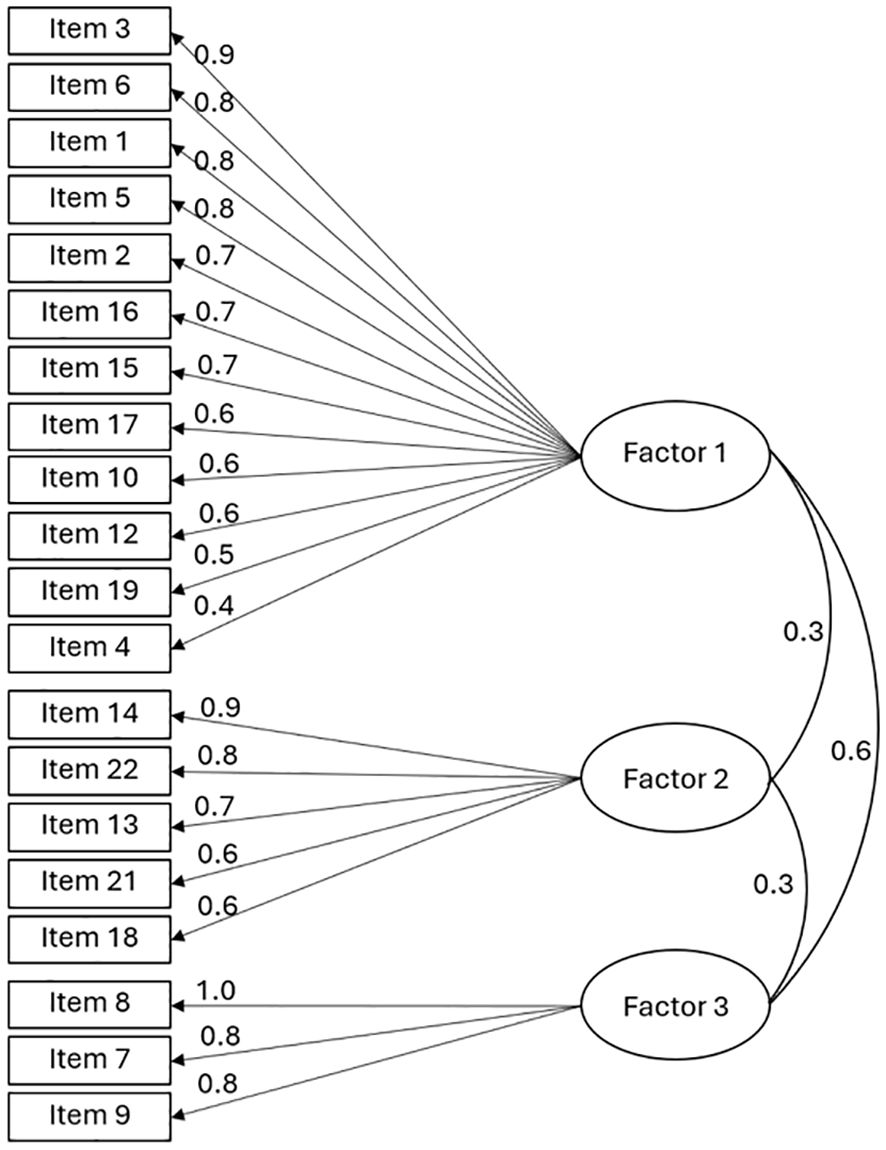

The first factor, labeled “AD Symptoms” (F1), includes items that assess the disproportionate affective symptoms of AD and accounts for 31% of the variance. The second factor, “Impact on Self-Care” (F2), is composed of items addressing the impact on illness-related behavior and explains 18% of the variance. The third factor, “Impact on Desire to Live” (F3), includes items related to death, suicide, and reasons for living. This factor shows a high correlation with the first factor and explains 15% of the variance. This correlation is conceptually plausible since suicidal ideation is part of the symptoms of AD.

Upon analyzing the factor loadings of items with this model, it was found that item 11 (“You have felt guilty about these stressful situations”) and item 20 (“You believe that you can do something to handle these stressful situations”) had low factor loadings. It was decided to remove these items because guilt might be a concept present in other disorders, such as depressive disorders, and therefore may not be specific enough; and the belief in the ability to do something, which measured self-efficacy, might be a statement that most people would consider true (as observed in the response frequencies), limiting the item’s usefulness in distinguishing between individuals with different levels of self-efficacy. A new EFA was conducted after excluding these items, which resulted in a similar three-factor configuration (Figure 2) explaining 67% of the variance (Table 7). This led to the final version of the ETAM with 20 items (Supplementary Material 1). It is worth noting that item 19 (“You feel that you need psychological help to cope with these stressful situations”) has a higher loading for F1, consistent with its formulation as part of the assessment of AD dysfunction, i.e., part of its symptoms and therefore was left in this dimension. However, it should not be ignored that it also had a burden for F2, of impact on self-care, which is also clinically consistent because seeking psychological help would be part of self-care.

Figure 2. Structure of the final 20-item version of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) from exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation. Items 11 and 20 were removed.

Table 7. Factor loadings for the three-dimensional structure of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) based on exploratory factor analysis without items 11 and 20.

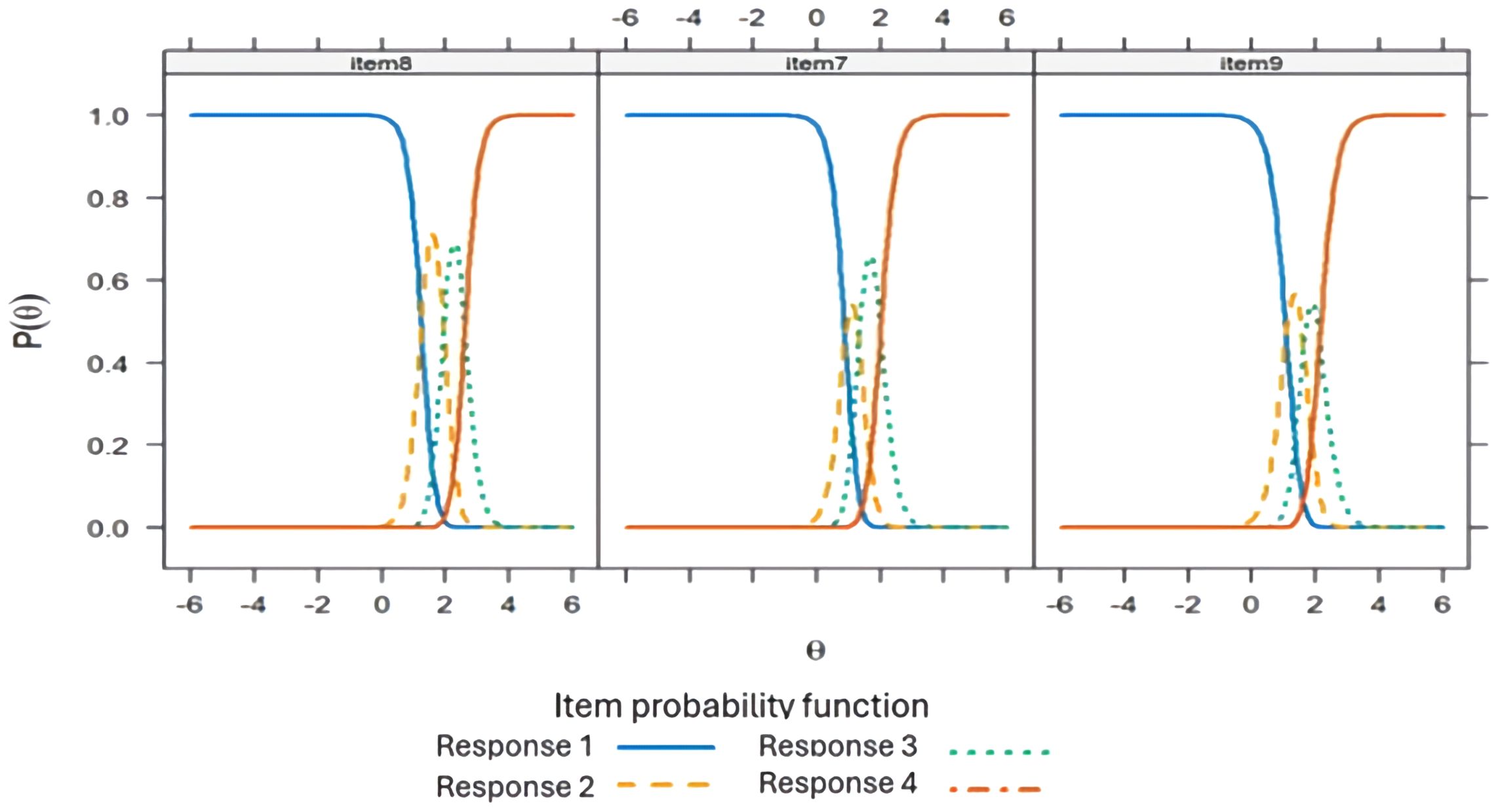

Item response theory analysisThe parameters of discrimination and difficulty (Table 8). In F1, items with the highest discrimination were item 1 (“You have felt sad about these stressful situations”), item 3 (“Because of these stressful situations you have felt anxious”), item 2 (“Because of these stressful situations, you have felt like crying”), and item 17 (“Your emotional reactions to these stressful situations are more intense than what is normal for you”). In F2, items 14 (“Because of these stressful situations you are less interested in following the treatments for your disease”) and 22 (“Because of these stressful situations, you are less interested in taking care of your health”) showed high discrimination. F3 was observed to be the dimension with the highest discrimination compared to the other dimensions, relating to ideas of death and suicide. The infit was adequate for all items and the outfit was acceptable, except for items 7,8, and 9 in F2. CRC for each item in the three dimensions of the ETAM are presented (Figures 3–5). Overall, the order of response options was maintained across all items of the scale.

Table 8. Discrimination and difficulty parameters of the twenty items* of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM), according to the generalized partial credit model of item response theory, and their model fit indexes.

Figure 3. Response category characteristic curve for the items of Dimension 1 of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) using a generalized partial credit model.

Figure 4. Response category characteristic curve for the items of Dimension 2 of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) using a generalized partial credit model.

Figure 5. Response category characteristic curve for the items of Dimension 3 of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM) using a generalized partial credit model.

Internal consistencyEvidence of adequate internal consistency was found. The McDonald’s Omega coefficient for F1, F2, and F3, it was 0.92 (95%CI: 0.91 – 0.93), 0.83 (95%CI: 0.80 – 0.86), and 0.86 (95%CI: 0.82 – 0.90), respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha for F1 was 0.92 (95%CI: 0.91 – 0.93), for F2 was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.81 – 0.85), and for F3 was 0.84 (95%CI: 0.82 – 0.87).

Test-retest reliabilityA total of 62 patients were evaluated for this property, of which 41 remained stable according to the external criterion of the CGI completed by both the patient and the evaluator. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) between the two measurements was high for the total scale (ICC = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.96 – 0.99), F1 (ICC = 0.99; 95%CI: 0.83 – 1.00), and F3 (ICC = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.97 – 0.99), and adequate for F2 (ICC = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.67 – 0.72).

Criterion validityA total of 209 patients were assessed by an independent psychiatrist, with 65 (31.1%) meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of AD. Comparing with the scores of the total scale and its factors, the AUROC values were 0.99 (95%CI: 0.97 – 1.00) for the total score, 0.96 (95%CI: 0.91 – 1.00) for F1, 0.95 (95%CI: 0.91 – 0.99) for F2, and 0.87 (95%CI: 0.79 – 0.94) for F3. For the total score, a cutoff of 43 points or higher was determined, providing a sensitivity of 97.4%, specificity of 90.6%, with 92.9% of patients correctly classified, a positive likelihood ratio of 10.4, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.02.

Hypotheses testing for construct ValidityFor convergent validity, positive and moderate to high correlations were found between the ETAM and its dimensions with the HADS and the ADNM-8 (Table 9). The internal consistency reliability of the anxiety and depression subscales of the HADS in our sample was α=0.74 and α=0.71, respectively. Similarly, the ADNM-8 demonstrated adequate reliability for the preoccupation (α=0.86) and failure to adapt (α=0.82) subscales, as well as for the total scale (α=0.91).

Table 9. Convergent construct validity of the final 20-item version of the Adjustment Disorder Scale for Medically Ill Patients (ETAM).

Regarding discriminative validity, statistically significant differences were observed in the scores of patients with AD versus those without AD. The average score for patients with AD (n=65) was 54.2 (SD=6.3), whereas for those without AD (n=144), it was 35.1 (SD=6.8), with a large effect size (gHedges=2.75; 95%CI: 2.36 – 3.15).

DiscussionThis study developed a scale for diagnosing and assessing AD in medically ill patients in Colombia and found evidence of its content, structural, reliability, criterion, and convergent and discriminative construct validity. A new theoretical model for AD in medically ill patients was created to address the specific clinical characteristics of AD in this population. Although specific manifestations are added, the developed construct is not opposed to those defined by current diagnostic manuals such as DSM-5-TR (2) and ICD-11 (69), facilitating the unification of criteria, which could lead to a definition that can be systematically applied by mental health professionals in this population.

Evidence of content validity was found for the ETAM, a property seldom reported in diagnostic scale studies and absent in other scales measuring Adjustment Disorder (AD), but crucial for obtaining other validity evidences (70). In fact, during the development of cognitive interviews, we encountered difficulties in presenting patients with a pre-specified list of stressful situations, as is common in other instruments such as the ADNM (71), allowing patients to describe their own stressful experiences without additional cognitive effort is particularly important, considering that nearly 46% of the sample had low or no education levels.

The final 20-item structure of the ETAM revealed that the construct consists of three dimensions. The first dimension encompasses symptoms of AD (F1), the second addresses the impact on self-care (F2), and the third pertains to the impact on the desire to live (F3), all demonstrating adequate internal consistency. Literature typically establishes AD as a unidimensional construct, combining anxious and depressive symptoms as a reaction to a stressful event (72). In the ETAM, Dimension 1 refers to all clinical features of AD, with a high correlation to Dimension 3, which specifically includes thoughts of death and suicide. These symptoms are also captured in current diagnostic manuals (2, 69) and instruments based on them (52). However, the ETAM also includes specific clinical features of AD for the medically ill population, which are grouped in Dimension 2 (F2) “Impact on Self-Care.”

The impact on self-care is a clinically relevant dimension in the medically ill population and refers to manifestations of AD that lead to a decline in self-care. This decline can result in the abandonment of medical treatment and follow-up, leading to worse health outcomes (73), which is why it is important to include it in the conceptualization of AD in these patients. Self-care is understood as the activities an individual initiates independently to maintain health and life, making it an essential component of coping with medical conditions (74). This concept has been operationalized primarily into three components. One external self-care that alludes to actions taken for a particular physical condition. A psychological or internal dimension that includes the mental attitude toward these actions. And a relational dimension reflecting how individuals engage in self-care through interactions with others (75). The ETAM addresses precisely these aspects by evaluating the patient’s commitment to medical treatment, overall health maintenance, substance use, self-perceived defeat, and interpersonal relationship issues related to coping with stressors.

In the external component of self-care, the willingness to engage in positive actions and favorable experiences, such as adhering to medical treatment or maintaining a healthy lifestyle, can be compromised during AD. The interpersonal component, which involves seeking positive interactions with others to meet support and care needs, may be disrupted by emotional reactions to stressors, leading to difficulties in maintaining these interactions and resulting in interpersonal problems. In the internal component, AD can manifest as a loss of the ability to view oneself as a protector and a sense of dejection expressed as defeat. Some studies have indeed found a relationship between affective symptoms and components of self-care. For instance, in patients with heart failure, the relationship between depressive symptoms and self-care maintenance is mediated by self-confidence in self-care, such that more severe depressive symptoms diminish self-confidence in self-care, which in turn reduces the ability to sustain the external component of self-care over time (76).

The perception of defeat included in item 18 (“You feel that you have been defeated by these stressful situations”) of Dimension 2 (F2 - Impact on Self-Care) of the ETAM aligns with this internal component of self-care. The choice of such a term was aimed at maximizing content validity by using the exact words of the medically ill patients interviewed during the item generation phase. As a concept, defeat has been developed within evolutionary theories as a depressogenic event, based on observations from ethological research where socially defeated animals exhibit stress behaviors such as abandoning feeding, social isolation, and autonomic hyperactivity (77). This concept has been extrapolated to humans and beyond social contexts to describe the resulting feeling from failure or loss of life goals. The range of circumstances that can provoke a sense of defeat in humans has expanded beyond direct interpersonal conflict to include other situations perceived as failed struggles, which can lead to depressive and anxious symptoms as well as suicidal behavior (78).

In line with classical theories on human response to stressors, such as Hans Selye’s concept of final exhaustion (79) or Lazarus and Folkman’s theories on coping and appraisal (80, 81), there are dynamic states or phases in the interaction process with a stressor that can lead to unresolved issues, with a loss of coping ability and ongoing adaptation failure. It is possible that in patients with medical conditions, the stress from the disorder can become so intense that it eventually leads to a perception of defeat, a loss of interest in continuing treatments and self-care, and even thoughts of death and suicide. Indeed, when analyzing item response theory, the items related to self-care (F2) and the impact on the desire to live (F3) demonstrated the highest discrimination between individuals with high versus low levels of TA, as well as higher thresholds. These items require a greater level of the latent variable (AD) to be addressed and could provide valuable information for patients formally diagnosed with this condition. Future research could explore the behavior over time of patients with high levels of impact on self-care (F2), including perceptions of defeat, which may indicate different stress levels that predispose them to chronic forms or diagnostic category changes such as MDE. We must also emphasize that the structure found in this study is provisional [or hypothetical (29)] and must be confirmed in an independent sample.

We also conducted an analysis of the ETAM using IRT. One of the key advantages of this methodology is that it enables us to understand the difficulty of the items and the level of the measured trait in individuals, providing valuable insights into the construct being assessed. This approach has become an essential and complementary tool in the validation of scales measuring psychological conditions (82). With IRT, we can determine how much of the AD is required to respond to each item. This allows for selecting items suited to specific purposes and populations. For example, if a clinician aims to screen for AD in the general population, where the level of the trait is expected to be low, they can use the easier items. However, for evaluating the severity or classifying patients with more intense AD, more challenging items should be employed, as the items of F3, that are related to dead and suicide ideas (items 7, 8 and 9). Precisely in these items we found a low outfit, in the presence of good infit, which could be present with very high discrimination, although this index is sensitive to outliers (83).

In this study, we also found that the ETAM had adequate test-retest reliability, with a ICC of 0.98 consid

留言 (0)