Aeromonas veronii is a facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative bacterium that possesses both a unipolar flagellar system and lateral flagella. It is widely distributed in diverse aquatic environments and exhibits robust survival and motility capabilities. Among clinical Aeromonas species, A. veronii stands out as one of the most prevalent, accounting for approximately one-quarter of all cases (Figueras and Beaz-Hidalgo, 2015). This bacterium possesses the capability to secrete exotoxins including hemolysin, cytotoxic enterotoxin, serine protease, and collagenase (Prediger et al., 2020). Human infections primarily occur through avenues such as water pollution, food contamination, and wound infections. Infections of A. veronii manifest with mild symptoms such as diarrhea and wound swelling; however, severe cases can progress to gastroenteritis, sepsis, and organ failure, posing a threat to public health (Fernandez-Bravo and Figueras, 2020). Regrettably, there is a lack of comprehensive studies on the pathogenesis of A. veronii, significantly impeding our capacity to devise effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

In the majority of pathogenic bacteria, the intracellular concentration of the second messenger c-di-GMP serves as a determinant of their virulence status (Valentini and Filloux, 2019), orchestrating crucial virulence activities such as host cell adherence, secretion of virulence factors, cytotoxicity, invasion, evasion, and resistance to oxidative stress (Jenal et al., 2017; Hall and Lee, 2018). Furthermore, c-di-GMP also plays a crucial regulatory role in various cellular processes, such as motility, biofilm formation, development and morphogenesis (Jenal et al., 2017). Its synthesis and degradation are modulated by diguanylate cyclase (DGC) and phosphodiesterase (PDE). Given the critical importance of c-di-GMP, bacteria usually possess a diverse array of different DGCs and PDEs (Povolotsky and Hengge, 2012; Mata et al., 2018; Homma and Kojima, 2022). Additionally, signal input domains located in their N-terminals including the Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) domain, the GAF domain, the HAMP domain, and the phosphoacceptor receiver (REC) domain (Schirmer, 2016), facilitate a swift and accurate modulation of intracellular c-di-GMP levels in response to various environmental and cellular signals. This intricate interplay forms a complex c-di-GMP regulatory network, contributing to the precise regulation of bacterial physiological responses (Galperin et al., 2018; Randall et al., 2022). Two-component system (TCS) constitutes a crucial element in the aforementioned c-di-GMP regulatory network, which generally comprises a sensor kinase (SK) and a response regulator (RR). The classical SK usually comprises sensor domains, a histidine kinase (HK) domain and a histidine phosphotransfer (HPT) domain. These structures enable SK to perceive environmental signals and undergo autophosphorylation, which subsequently results in phosphotransfer to the RR. Typically, the RR is composed of an N-terminal regulatory domain and a C-terminal effector domain, and its biological function is dictated by the latter. For TCSs that associated with c-di-GMP modulations, certain RRs featuring GGDEF domains as their effector domain demonstrate DGC activity, including WspR, PleD, CfcR, CdgS (Galperin, 2010; Tagua et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2023); others possessing HD-GYP or EAL domains demonstrate PDE activity, including RocR, VieA, RavR, PvrR, and RpfG (Tamayo et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2009; Galperin, 2010; Cheng et al., 2019). Additionally, specific RRs, like Lpl0329 and Lpg0277, possess both types of the aforementioned domains and exhibit dual functionalities (Levet-Paulo et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2019). Consequently, these TCSs constituted critical regulatory pathways for the c-di-GMP metabolism in bacteria (Junkermeier and Hengge, 2023). They actively engage in the synthesis or degradation of intracellular c-di-GMP, and serve as precise instruments that effectively translate various signals from the environments or cells into intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations, thereby eliciting specific cellular responses and enabling bacteria to sensitively adapt to changes in their surroundings. Unfortunately, despite structural analyses suggesting that many TCSs in Aeromonas are associated with c-di-GMP metabolism based on their effector domains (GGDEF, HD-GYP, and EAL), their specific functions and regulatory mechanisms have rarely been experimentally validated. In A. veronii, genome sequencing revealed the presence of 36 proteins containing the GGDEF domain, 16 proteins with the EAL domain, and 11 proteins with the HD-GYP domain. However, only the functions of UZE59342.1 (CsrD) and UZE59093.1 (AHA0701h) had been experimentally verified (Kozlova et al., 2012; Gladyshchuk et al., 2024).

In our preceding investigation, we identified an uncharacterized TCS in A. veronii (Liu et al., 2015), where its SK, denoted as ArrS and encoded by ONR73_07150, exhibited structural similarities with BvgS of Bordetella pertussis; and its RR, denoted as ArrR and encoded by ONR73_07145, featured an EAL domain at C-terminus. In this study, we confirmed the formation of a TCS where ArrS-mediated phosphorylation hindered the PDE activity of ArrR. Additionally, we presented cogent evidences supporting the involvement of ArrS/ArrR in intracellular c-di-GMP catabolism, showcasing its influence on biofilm formation, motility, and virulence in A. veronii. Moreover, we discovered an ARG-BOX motif situated within the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter of arrS, and identified ArgR as a transcriptional repressor for the arrSR operon. In conclusion, our findings identified a novel TCS associated with c-di-GMP metabolism and virulence, offering theoretical foundations for potential interventions against A. veronii infections.

Methods Bacterial strains and culture conditionsStrains and plasmids employed in this study were detailed in Supplementary Table S1. The E. coli WM3064 strain, an auxotrophic strain that relies on diaminopimelic acid (DAP), was utilized as the donor strain for transferring plasmids into A. veronii through bacterial conjugation. The ΔarrS strain denoted an A. veronii mutant harboring a deletion mutation (from 271 to 668 bp) in arrS gene, whereas the ΔarrR strain represented an A. veronii knockout strain lacking the full-length arrR gene. Consequently, ΔarrSΔarrR represented a corresponding double knockout strain. Unless otherwise stated, all strains were cultured on Luria Bertani cluture (LB), maintaining a temperature of 30°C for A. veronii and 37°C for E. coli. Antibiotic was used based on the specific plasmid carried by each strain, with final concentrations as follows: ampicillin (Amp) at 50 μg/mL, chloramphenicol (Cm) at 25 μg/mL, kanamycin (Km) at 50 μg/mL, and tetracycline (Tc) at 12.5 μg/mL.

Construction of recombinant plasmidsPlasmids employed in constructing recombinant vectors were listed in Supplementary Table S1, and all utilized primers were provided in Supplementary Table S2. In this study, two methods were utilized for the construction of recombinant vectors: the conventional method involved the use of restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase, while the other one utilized an Ultra One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, China) that achieved directional cloning through the recombinase-mediated recombination. The latter was used for the insertion of multiple fragments into the plasmids.

Using the genomic DNA of A. veronii WT as template, the arrS promoter (P arrS) was cloned using primers P arrS-F/R to construct pBXcmT-P arrS; the HPT domain of ArrS was cloned using primers pTRGHPT-F/R to construct pTRG-HPT; the REC domain of ArrR was cloned using primers pBTREC-F/R to construct pBT-REC; the ArrS820-1414 was cloned using primers pETArrS-F/R to construct pET28a-ArrS; the ArrR was cloned using primers pETArrR-F/R to construct pET28a-ArrR. Using the genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa as template, the dgcH was cloned using primers DgcH-F/R to construct pBBR-dgcH.

To obtain pET28a-ArrRm, point-mutant PCR was performed on pET28a-ArrR. The phosphorylation site of the REC domain was mutated to alanine (D59A) using primers ArrRm-F/R, followed by mutation of the Mg2+ binding site (E14A, D15A) using primers ArrRm2-F/R. To obtain pBXcmT-P arrSm, point-mutant PCR was performed on pBXcmT-P arrS using primers AGRm-F/R to introduce mutations at its ARG-BOX. To obtain pBBR-ArrRaal, point-mutant PCR was performed on pBBR-ArrR using primers AAL-F/R, and the critical glutamate of EAL domain was mutated to alanine (E176A). To obtain pBBR-ArrRm, the mutated arrR was cloned from pET28a-ArrRm using primers pBBRarrR-F/R and ligated together with P arrS.

Construction of the knockout and complementary strainsThe allele-exchange vector pRE112 was utilized for arrS and arrR knockout through homologous recombination. To induce genetic recombination, the upstream and downstream homologous arms flanking the target fragment should be positioned in close proximity to each other. In pRE112-arrS, homologous arms flanking the arrS gene segment (from 271 to 668 bp) were cloned using primers arrSarm1-F/R and arrSarm2-F/R, respectively; whereas in pRE112-arrR, homologous arms flanking the whole arrR gene were cloned using primers arrRarm1-F/R and arrRarm2-F/R. Under the help of the donor strain E. coli WM3064, pRE112-arrS and pRE112-arrR were transformed into A. veronii via bacterial conjugation. Subsequently, A. veronii carrying pRE112-arrS or pRE112-arrR was cultured overnight in non-antibiotic LB for the first recombination, and then grow on LB plates containing 22% sucrose and 25 μg/μL Amp for the second recombination. Knockout strains were verified by colony PCR using primers pairs arrS-F0/R0 for ΔarrS and arrR-F0/R0 for ΔarrR, followed by confirmation of sequencing analysis.

The broad-host-range shuttle vector pBBR1MCS-2 was employed for the construction of arrS or arrR complementation strains. For pBBR-arrS, the full-length arrS gene and its promoter were cloned from the A. veronii genome using primers pBBRarrS-F/R; For pBBR-arrR, the full-length arrR gene and P arrS were cloned and ligated adjacently using primers pBBRP arrS-F/R and pBBRarrR-F/R. Subsequently, ΔarrS with pBBR-arrS and ΔarrR with pBBR-arrR were obtained through bacterial conjugation, serving as the complementation strains for ΔarrS and ΔarrR, respectively.

Protein expression and purificationThe expressions of ArrS820-1414, ArrR, ArrRm, and ArgR were induced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) at 16°C. Subsequent to induction, the cells were harvested using a 50 mM pre-cooled Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and subjected to sonication on ice for 15 min. Following centrifugation at 4°C, the resulting crude protein extracts underwent purification through Ni-NTA agarose gel, employing affinity chromatography. ArrS820-1414 and ArgR were eluted using a 250 mM imidazole buffer, whereas ArrR and ArrRm were eluted using a 150 mM imidazole buffer. The eluted solution, enriched with the target proteins, was screened with G-250, dialyzed in a solution containing 50 mM Tris–HCl and 20% glycerol at pH 8.0, partitioned into 2 mL centrifuge tubes, and subsequently stored at −80°C.

Phosphorylation and phosphotransferArrS820-1414, ArrR, and ArrRm underwent phosphorylation in a phosphorylation buffer composed of 50 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM Dithiothreitol, at a pH of 8.0. For the autophosphorylation, 5 mg of ArrS820-1414 or ArrR were separately incubated with 100 μM ATP in 50 μL of phosphorylation buffer at room temperature for 30 min. For the phosphotransfer, additional 1 mg of ArrS820-1414 was added.

Detection of the phosphodiesterase activityThe procedure for detecting PDE activity was as previously outlined by Bobrov and He Chenyang (Bobrov et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2012). In this investigation, 200 ng each of ArrS820-1414, ArrR, or ArrRm were individually incubated with 10 mM bis (4-nitrophenyl) phosphate (BNPP) in the PDE buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM MnCl2, pH 8.5) at 30°C. The PDE activity was evaluated based on the release rate of p-nitrophenol in the reaction mixtures, quantified by measuring OD410.

Quantification of intracellular c-di-GMP levelsThe fluorescence reporter vector pBBR-P cdrA-GFP was constructed to quantify the intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations. In this construct, the promoter region of cdrA from P. aeruginosa (from −290 to +12 bp) was placed upstream of the GFP gene. The interaction of c-di-GMP with FleQ (encoded by ONR73_15360 in A. veronii) would lead to transcriptional derepression of P cdrA, thereby enabling enhanced transcriptional activity in response to c-di-GMP binding (Rybtke et al., 2012). Thus, pBBR-P cdrA-GFP established a direct proportional relationship between fluorescence intensity and intracellular c-di-GMP levels. Intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations can be quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength of 479 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. Furthermore, liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS) was employed as well to quantify the intracellular c-di-GMP levels, as detailed by Bahre and Kaever (2017). 5 mL of bacteria were collected and the c-di-GMP was extracted by 1 mL of extraction solution (40% methanol, 40% acetonitrile, 20% water). The protein precipitates were stored at −20°C for total protein quantification, while the supernatant was transferred into a 10 mL centrifuge tube for lyophilization and redissolution. These samples were compared against a standard curve derived from measurements of c-di-GMP standard substances with known concentrations (Merck, China). The intracellular c-di-GMP levels were then normalized against total protein contents and expressed as pmol of c-di-GMP/mg of total protein.

Bacteria two-hybrid and one-hybrid assaysThe bacterial two-hybrid system (Joung et al., 2000) was employed to investigate the interaction between ArrS and ArrR. The HPT domain of ArrS was fused with RNA polymerase alpha subunit (RNAPα) in the pTRG-HPT plasmid, whereas the REC domain of ArrR was fused with λcI in the pBT-REC plasmid. These plasmids were co-transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′, followed by overnight culture in M9+ His-dropout broth, gradient dilution, and growth on dual-selective solid medium with 10 mM 3-aminotriazol (3-AT) and 12.5 μg/mL streptomycin. The co-transformed strain carrying pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11p served as the positive controls.

The bacterial one-hybrid system (Guo et al., 2009) was utilized to verify the interaction between ArgR and P arrS. The plasmid pTRG-ArgR expresses a fusion protein of ArgR and RNAPα, while the plasmid pBXcmT-P arrS has the promoter P arrS (from −132 to +3 bp) inserted before the HIS3-aadA reporter. Moreover, point mutation PCR was conducted on pBXcmT-P arrS to introduce a 2-bp point mutation in the ARG-BOX of P arrS, resulting in pBXcmT-P arrSm. The co-transformed strain of pBXcmT-P arrS and pTRG-SmpB was utilized as a positive control (Liu et al., 2015).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq)ChIP-seq was performed as previously described by Wang et al. (2024). The WT strain carrying pBBR-argR was cultured in M9 medium, collected by centrifugation, and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. The cross-link was quenched with 125 mM glycine. Subsequently, the bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with pre-cooled PBS buffer, preserved on dry ice, and dispatched to SEQHEALTH (Wuhan, China) for ChIP-seq analysis to identify the target genes of ArgR. FLAG antibodies were employed for the immunoprecipitation of DNA-protein complexes. The raw data were subjected to quality assessment using FastQC (v0.11.5) and subsequently refined using Trimmomatic (v 0.39) before being mapped to the genome of WT. ArgR peaks were generated and visualized using MACS2 (v2.1.2) and the IGV Viewer (v 2.11.2), respectively.

Electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) assayThe primers P arrS-R was labeled with 6-Carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) at its 5′ end, and P arrS-F and P arrS-R were used to amplified the luciferase-modified P arrS, as well as its mutated ARG-BOX variant, P arrSm. For EMSA, various concentrations of P arrS or P arrSm were separately incubated with ArgR in EMSA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol) at room temperature. Then the reaction mixtures were subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel using Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer. Following 2 h of electrophoresis at 4°C, the migration of P arrS or P arrSm was visualized using a biomolecular imager Typhoon FLA9500 (GE Healthcare, America).

Biofilm detectionBiofilm formation was assessed using the crystal violet method, performed in 96-well microtiter plates (Coffey and Anderson, 2014). 100 μL of the bacterial suspension at a final OD600 of 0.1 was aliquoted into separate wells in a 96-well PVC plate and incubated in a stationary position for 24 h. After incubation, the plate was washed three times and treated with 150 μL methanol for 20 min, followed by air-drying and staining with 150 μL of 0.5% crystal violet for an additional 20 min. Excess crystal violet was removed by flowing water, and 150 μL of 33% acetic acid was added to each well after drying. Following a 30-min incubation at 37°C, biofilm formation was quantified by measuring the OD590.

Motility detectionThe overnight-cultured strains were washed, resuspended in PBS buffer, and diluted to an OD600 of 2. For swimming, 2.5 μL of the aforementioned bacterial solution was spotted onto swimming semi-solid plates (composed of 1% peptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.25% agar). After culturing for 10 h, these plates were further incubated at 4°C for an additional 12 h to enhance the visibility of the swimming zone. The swimming radii were then measured. For swarming, an additional 2.5 μL of the bacterial solution was spotted onto swarming semi-solid plates (consisting of 1% peptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.35% agar), and the swarming radii were measured following a 16-h incubation.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)Aeromonas veronii WT and ΔarrS were cultured in LB for 21 h with an initial optical density (OD600) of 0.01. The bacteria were then collected by centrifugation, and total RNA was extracted using the Bacteria Total RNA Isolation Kit (Sangon, Shanghai), and reverse transcription was then performed using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing). Subsequently, qPCR system was configured with the ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing). RT-qPCR was performed on the Recho LightCycler 96 using a two-step method. The relative transcription level was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with the DNA helicase gyrB as the reference gene.

Proteomic analysisAfter overnight culture in LB, the activated A. veronii WT and ΔarrS were inoculated into fresh LB at an optical density (OD600) of 0.01, and continued to be cultured at 150 rpm for 18 h. Subsequently, WT and ΔarrS were harvested by centrifugation, frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored on dry ice, and sent to APTBIO (Shanghai, China) for label-free quantitative proteomics. The technical workflow encompasses protein extraction, protein quantification, enzymolysis, LC–MS/MS, database searching, and bioinformatics analysis. The acquired raw data were processed using MaxQuant (v1.6.2.0) for database searching and quantitative analysis. The Gene Ontology annotation of all differentially expressed proteins was performed using Blast2GO (v 5.2.5) (Gotz et al., 2008).

Ultraviolet radiation detectionThe overnight-cultured A. veronii WT, ΔarrS and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS were collected, resuspended in PBS buffer, and diluted to a concentration of 107 CFU/mL. Then 10 mL of the bacterial suspension was poured onto a 90 mm plate and exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation for 60 s using a UV-light cross-linker SCIENTZ 03-II (SCIENTZ, China), with a wavelength of 254 nm and power intensity of 4 mW/cm2. 100 μL of the irradiated bacterial solution was then applied onto LB plates and incubated in darkness for 24 h. The colony-forming units (CFUs) on the plate were counted to determine the survival rate.

Toxicity challenge in miceKunming mice were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd., and all procedures followed the Hainan University Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hainan University. Five-week-old mice were allocated into four groups, each consisting of six individuals. Three of them received intraperitoneal injections of WT, ΔarrS and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS at a dose of 105 CFU/g, while the remaining group was injected with 100 μL PBS buffer as a control. Then, the mice fasted for 24 h and their survival rate was monitored for 7 days. Simultaneously, four additional groups of mice underwent intraperitoneal injection as well, and their orbital blood was collected 12 h later. The quantifications of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-6 in serum were determined by an ELISA kit (Meibiao Biotechnology, Jiangsu). After blood collection, the mice were immediately dissected, and their spleen, kidney, and liver were washed and weighed. A portion of these organs was homogenized using a tissue crusher, followed by dilution and plating on LB plates with ampicillin for the quantification of A. veronii burdens. Another portion was treated with 4% paraformaldehyde and prepared for paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE), ultimately undergoing pathological observation under a microscope.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis and graphical representation were carried out using GraphPad Prism v8.0.2 (GraphPad, America), with a minimum of three replicates per experiment. Significance was assessed using multiple t-tests, with error bars representing standard deviation (SD). The symbol “*” denoted significant difference (p < 0.05) and “**” denoted extremely significant difference (p < 0.01), while “ns” denoted no significant difference.

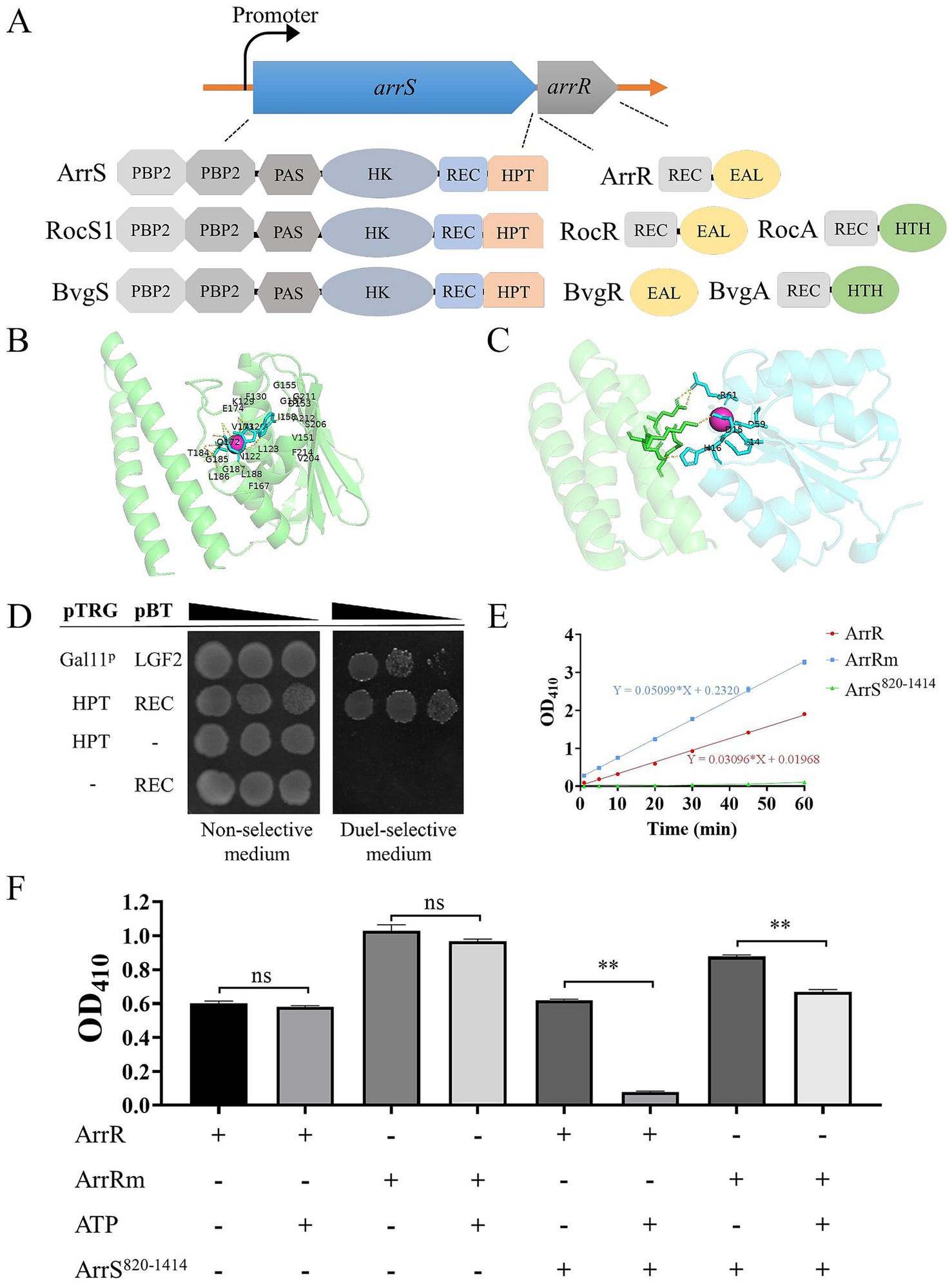

Results ArrS and ArrR constitute a TCSThe conserved domains of ArrS and ArrR were analyzed by CD-search (Lu et al., 2020), and the results were presented in Figure 1A. ArrS exhibited common domains with BvgS from Bordetella pertussis and RocS1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. All of them consisted of two type-2 periplasmic-binding fold protein (PBP2) domains at periplasmic region, followed by a PAS domain, an HK domain, a REC domain, an HPT domain in the cytoplasmic region. Notably, ArrR shared a similar structural composition with RocR, both of them encompassed a REC domain and an EAL domain. The same domains suggested ArrS and ArrR might form a functional TCS like RocS/RocR. Additionally, as depicted in Supplementary Figures S1, S2, arrS and arrR were co-transcribed and were observed across at least 15 Aeromonas, including the most common clinical species (A. caviae, A. dhakensis, A. veronii, A. hydrophila). These discoveries reinforced our argument. But in contrast to their homologous TCS counterparts in B. pertussis and P. aeruginosa, in the proximity of ArrS/ArrR there was no gene similar to bvgA or rocA that encoding a transcription factor, indicated ArrS and ArrR constituted a distinctive TCS.

Figure 1. Formation of a functional TCS by ArrS and ArrR. (A) Comparative structural analysis of ArrS, ArrR and their homologous proteins. (B) Autophosphorylation model. The green region indicates the HPT domain of ArrS, the red spheres represent Mg2+, and the blue region represents ATP. Residue numbering begins at the first residue of the HPT domain. (C) Interaction model. The green region represents the HPT domain of ArrS, the blue region represents the REC domain of ArrR, and the red spheres represent Mg2+. (D) Confirmation of the interaction between the HPT domain and REC domain via two-hybrid. The co-transformed strain containing pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11p was used as the positive control. (E) Assessment of the PDE Activity. Using 10 mM BNPP as the substrate, PDE activity were quantified by measuring the release rate of p-nitrophenol (OD410). (F) Investigation of the PDE activity and phosphotransfer. ArrR or ArrRm were incubated with ArrS, ATP or both in PDE buffer for 20 min. Experiments were replicated three times in panels (E,F). p-values were obtained from t-tests and the error bars indicate the SD. **denoted extremely significant difference (P<0.01).

To establish the existence of a novel TCS consisting of ArrS and ArrR, we initially employed AlphaFold 3 to simulate the ATP binding ability of ArrS and its interaction with ArrR. The pLDDT scores and the PAE plots of above models were shown in Supplementary Figure S3. The autophosphorylation model (Figure 1B) showed that ATP and Mg2+ were encapsulated within the pocket of the HK domain, with ipTM and pTM scores of 0.96 and 0.83, respectively. The residues predicted to interact with ATP and Mg2+ in this model were consistent with those identified by CD-search, strongly indicating that ArrS possesses autophosphorylation activity. The interaction model (Figure 1C) showed that the HPT domain of ArrS interacted with the REC domain of ArrR in the presence of Mg2+, with ipTM and pTM scores of 0.8 and 0.87, respectively. Once again, the AlphaFold 3 model and the CD search analysis were consistent. The key residues annotated by the CD-search were shown in Supplementary Figure S4. In conclusion, the models predicted by AlphaFold 3 strongly support the possibility that ArrS and ArrR form a TCS.

Subsequently, we examined the interaction between ArrS and ArrR using a bacteria two-hybrid system. In the study of RocR and RocS1, the HPT domain and the REC domain were used for detecting the interaction between SK and RR (Kulasekara et al., 2005). Consequently, we cloned the HPT domain of ArrS into the pTRG plasmid and the REC domain of ArrR into the pBT plasmid. As depicted in Figure 1D, the co-transformated strains carrying pTRG-HPT and pBT-REC exhibited enhanced growth in dual-selective medium compared to the positive control containing pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11p. This observation demonstrated a robust interaction between the HPT domain and REC domain, confirming the binding of ArrS to ArrR.

Generally, SK regulates the active state of RR through phosphotransfer. Thus, we verified the occurrence of phosphotransfer by examining the effect of ArrS on the PDE activity of ArrR. As shown in Supplementary Figure S5, we expressed and purified the truncated ArrS, the full-length ArrR, and the mutated ArrR in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The truncated ArrS, denoted as ArrS820-1414, omitted the PBP2 and PAS domains at C-terminus while retaining the domains responsible for autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer, which is more suitable for expression and purification. The mutated ArrR, denoted as ArrRm, harbored point mutations at G14, D15 and D59 that are critical for REC domain (Supplementary Figure S4), rendering it theoretically unresponsive to accept phosphate from ArrS. Firstly, we verified the PDE activity of ArrR and ArrRm using BNPP as the substrate. As shown in Figure 1E, BNPP continued to decompose in the presence of ArrR, confirming the PDE activity of ArrR; the decomposition rate of BNPP treated with ArrRm was slightly but significantly higher than that of ArrR (approximately 1.65 times), indicating that the non-phosphorylated form of ArrR possesses strong PDE activity. Subsequently, we investigated the PDE activity of ArrR and ArrRm when incubated with ArrS820-1414, ATP, or both. As illustrated in Figure 1D, ATP alone did not significantly influence the PDE activity of ArrR or ArrRm, nor did ArrS. However, after incubation with both ArrS820-1414 and ATP for 20 min as shown in Figure 1F, the PDE activity of ArrR decreased to 12.57%, while ArrRm retained 76.25% of its PDE activity under identical condition. The impact exerted by ArrS820-1414 and ATP on ArrRm was significantly lower than that observed for ArrR. This phenomenon suggested that the PDE activity of ArrR was inhibited by ArrS-mediated phosphorylation, along with the occurrence of phosphotransfer from ArrS to ArrR.

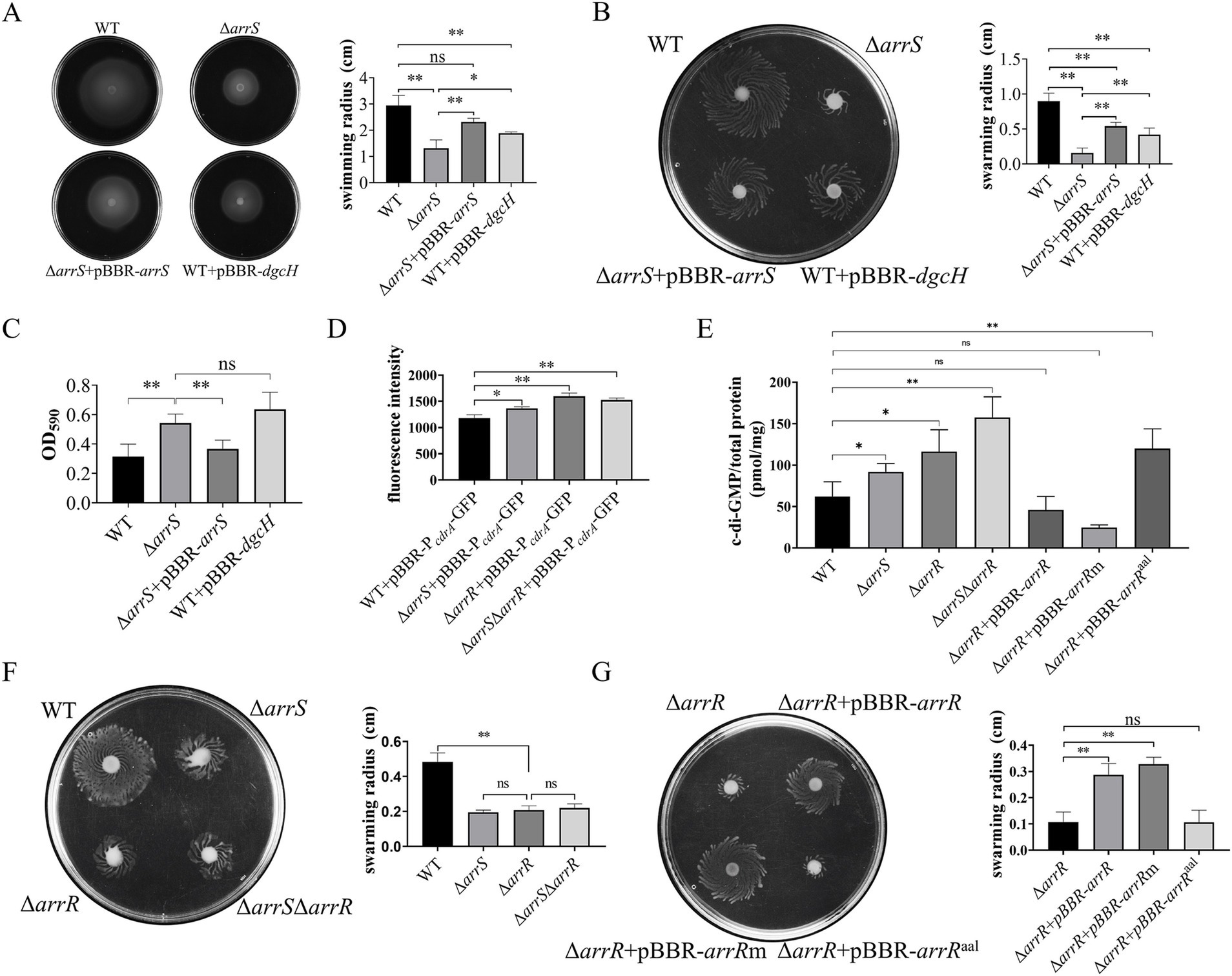

ArrS and ArrR alter the intracellular c-di-GMP concentrationMotility and biofilm formation represent two prominent phenotypes in bacteria that are influenced by the intracellular c-di-GMP levels. Thus, we conducted an initial assessment of the influence of ArrS on intracellular c-di-GMP levels by assessing motility and biofilm formation. As illustrated in Supplementary Figure S6, we generated the A. veronii arrS knockout strain ΔarrS, and deletion of arrS demonstrated no discernible impact on the growth in A. veronii. Furthermore, ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS and WT + pBBR-dgcH were generated as well and served as controls. DgcH is a guanylate cyclase from P. aeruginosa and its expression will lead to an elevated c-di-GMP levels in cells (Liu et al., 2023).

The motility findings are illustrated in Figures 2A,B. The mean swimming radius for ΔarrS was 1.32 cm, whereas the mean swimming radii for WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS were 2.23-fold and 1.76-fold greater than that of ΔarrS, respectively. Similarly, the swarming radii exhibited comparable trends. The mean swarming radius for ΔarrS was 0.158 cm, while the mean swarming radii for WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS were 5.70-fold and 3.43-fold greater, respectively. For WT + pBBR-dgcH, the average swimming and swarming radii were 1.89 cm and 0.418 cm, respectively, falling within the range observed for ΔarrS and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS. Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 2C, the amount of biofilm generated by WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS was determined to be 57.8 and 67.5% of that produced by ΔarrS, respectively. In contrast, WT + pBBR-dgcH exhibited a slightly higher amount of biofilm compared to ΔarrS. ΔarrS exhibited enhanced biofilm formation but weaker motility, which is consistent with previous observations of A. veronii under elevated c-di-GMP concentrations (Rahman et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2021). Additionally, the phenotypic similarities between WT + pBBR-dgcH and ΔarrS provide further evidence suggesting that these observations should be attributed to an increased concentration of c-di-GMP in vivo.

Figure 2. Regulation of c-di-GMP mediated by ArrS and ArrR. (A) Evaluation of the influence of ArrS on swimming ability. (B) Assessment of the effect of ArrS on swarming ability. (C) Detection of the impact of ArrS on biofilm formation. Biofilm quantity was assessed by measuring the intensity of crystal violet (OD590). (D) Measurement of the intracellular c-di-GMP levels using pBBR-P cdrA-GFP. The fluorescence intensity was directly correlating with intracellular c-di-GMP levels. (E) Quantification of the intracellular c-di-GMP levels using LC–MS. (F) Verification of the swarming ability for knockout strains and (G) complementary strains. Experiments were replicated three times in panels (A,D), while four times in panels (B,E,F,G), and five times in panel (C). p-values were obtained from t-tests and the error bars indicate the SD.

To prove this speculation, we constructed a fluorescence reporter vectors, namely pBBR-P cdrA-GFP, to assess the intracellular c-di-GMP levels in A. veronii. In P. aeruginosa, the FleQ protein binds to the promoter region of the cdrA gene and inhibits its transcription, while the binding of c-di-GMP to FleQ alleviates this inhibitory effect (Rybtke et al., 2012). Consequently, the fluorescence intensity observed in A. veronii with pBBR-P cdrA-GFP should be directly proportional to the intracellular c-di-GMP concentration. As depicted in Figure 2D, the mean fluorescence value of pBBR-P cdrA-GFP in WT was 1178.3, significantly lower than that of ΔarrS, with a mean fluorescence value of 1366.7. This result reconfirmed that the intracellular c-di-GMP in WT was significantly lower than that in ΔarrS.

Elevated c-di-GMP levels in ΔarrS were unexpected, given its capacity to inhibit the PDE activity of ArrR. Consequently, we further generated A. veronii knockout strains ΔarrR and ΔarrSΔarrR, followed by a quantitative analysis of intracellular c-di-GMP levels using the pBBR-P cdrA-GFP and the LC–MS. As depicted in Figure 2D, the fluorescence intensity was 1596.8 in ΔarrR and 1525.0 in ΔarrSΔarrR, both significantly higher than that in WT. In alignment with the aforementioned findings, LC–MS analysis (Figure 2E) revealed that the intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations was 91.86 pmol/mg in ΔarrS, 116.17 pmol/mg in ΔarrR, and 157.54 pmol/mg in ΔarrSΔarrR. All of them were significantly higher than that in WT (62.00 pmol/mg). This finding corroborated again that the deletion of arrS indeed led to an increase in intracellular c-di-GMP observed in vitro, indicating ArrS might have an alternative mechanism besides phosphorylating ArrR. Furthermore, although the c-di-GMP concentration in ΔarrSΔarrR was higher than ΔarrR, no statistically significant difference was observed between the c-di-GMP concentrations in ΔarrSΔarrR and ΔarrR. Consistently, as shown in Figure 2F, no significant difference was observed in the swarming radii of ΔarrS, ΔarrR, and ΔarrSΔarrR. This indicated that ArrS and ArrR should achieve their functions in a common mechanism, which is a two-component system.

To demonstrate the observed intracellular c-di-GMP fluctuation was attributed to the PDE activity of ArrR, we constructed complementation strains for ΔarrR using original ArrR, phosphorylation-insensitive ArrRm and PDE-inactivated ArrRaal, respectively. As depicted in Figure 2E, the c-di-GMP content was measured as 46.01 pmol/mg for ΔarrR + pBBR-arrR, 24.55 pmol/mg for ΔarrR + pBBR-arrRm, and 120.01 pmol/mg for ΔarrR + pBBR-arrRaal. The observed alterations were consistent with the expected PDE activity of ArrR, ArrRm and ArrRaal. Complementation with ArrR or ArrRm significantly reduce the intracellular c-di-GMP levels, whereas complementation of ArrRaal lacking PDE activity had minimal impact. Similarly, these strains exhibited comparable performance in swarming ability, as illustrated in Figure 2G. Furthermore, a consistent trend was observed in both the biofilm formation and swimming motility (Supplementary Figure S7). In conclusion, above findings supported our hypothesis that the PDE activity of ArrR modulates the intracellular c-di-GMP levels of A. veronii.

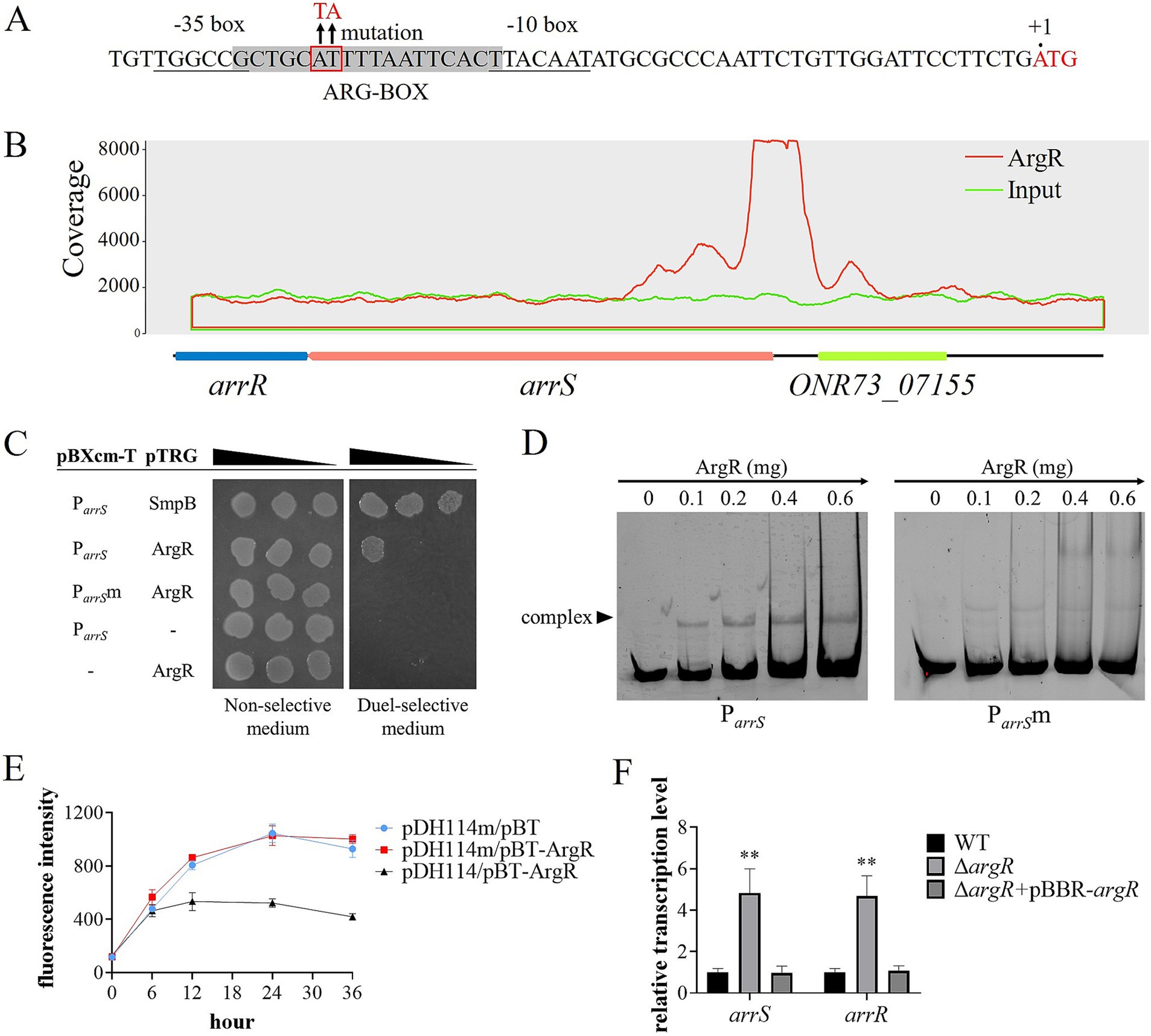

ArgR functions as the transcriptional repressor of arrSThe sequence analysis of P arrS revealed an ARG-BOX (Cho et al., 2015) located between the −10 and −35 regions, as depicted in Figure 3A. The ARG-BOX serves as the binding site for the global transcription factor ArgR, which plays a crucial role in regulating arginine metabolism and transport. Additionally, the results of ChIP-Seq indicated a substantial enrichment of P arrS by ArgR (Figure 3B), with a pileup ratio 22.86 times that of the input. These findings prompted our suspicion of a direct interaction between ArgR and P arrS. Thus, the bacterial one-hybrid was conducted and the results were shown in Figure 3C, where E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ carrying pBXcmT-P arrS and pTRG-ArgR exhibited robust growth on the dual-selective medium. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 3D, P arrS labeled with 6-FAM was retained in the EMSA assay following incubation with ArgR. When a point mutation illustrated in Figure 3A was introduced into the ARG-BOX of P arrS, XL1-Blue MRF′ carrying pBXcmT-P arrSm and pTRG-ArgR failed to grow on the dual-selective medium (Figure 3C) and P arrSm did not exhibit retention during gel electrophoresis (Figure 3D). These evidences demonstrated the binding ability of ArgR to P arrS and the dependence of ArgR binding on ARG-BOX.

Figure 3. ArgR as a transcriptional repressor of arrSR. (A) P arrS and its mutation sites at ARG-BOX. ARG-BOX was highlighted in gray, −10 and −35 regions were demarcated by underline, and the mutation site was located within the red frame. (B) ChIP-seq revealed ArgR binding to P arrS. The peaks of ArgR and input were depicted by red and blue curves respectively, with the corresponding genomic positions illustrated below. (C) Verification of ArgR binding to P arrS via one-hybrid. The mutation sites of P arrSm were shown in panel (A). (D) Verification of ArgR binding to P arrS via EMSA. P arrS and P arrSm were labeled with 6-FAM and separately incubated with varying concentrations of ArgR. (E) Validation of the transcriptional function of ArgR via fluorescent reporter. The expression of GFP was regulated by P arrS in pDH114 and P arrSm in pDH114m, while pBT-ArgR was used to express ArgR. (F) Confirmation of ArgR inhibition on arrSR via RT-qPCR. Experiments in panels (E,F) were conducted with five replicates. p-values were obtained from t-tests and the error bars indicate the SD. **denoted extremely significant difference (P<0.01).

To investigate the effects of ArgR binding on P arrS, we used a fluorescence plasmid, pDH114, which expresses GFP under the control of P arrS (Liu et al., 2015). Furthermore, we constructed pDH114m, a mutant version that incorporated mutations in its ARG-BOX while maintaining its promoter activity (Supplementary Figure S8). The fluorescence intensity of E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ carrying pDH114 or pDH114m was detected in the presence or absence of ArgR. As depicted in Figure 3E, when ArgR was expressed by the pBT-ArgR plasmid, there was a significant reduction in the fluorescence intensity of host cells carrying pDH114. However, for pDH114m, no change was observed upon ArgR expression. These results suggested that ArgR inhibited the transcription of P arrS. Moreover, the reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis yielded similar results, as exhibited in Figure 3F. The transcription levels of both arrS and arrR in ΔargR was significantly higher than those observed in WT and ΔargR + pBBR-argR, indicating that the knockout of ArgR alleviated its restriction on arrS transcription.

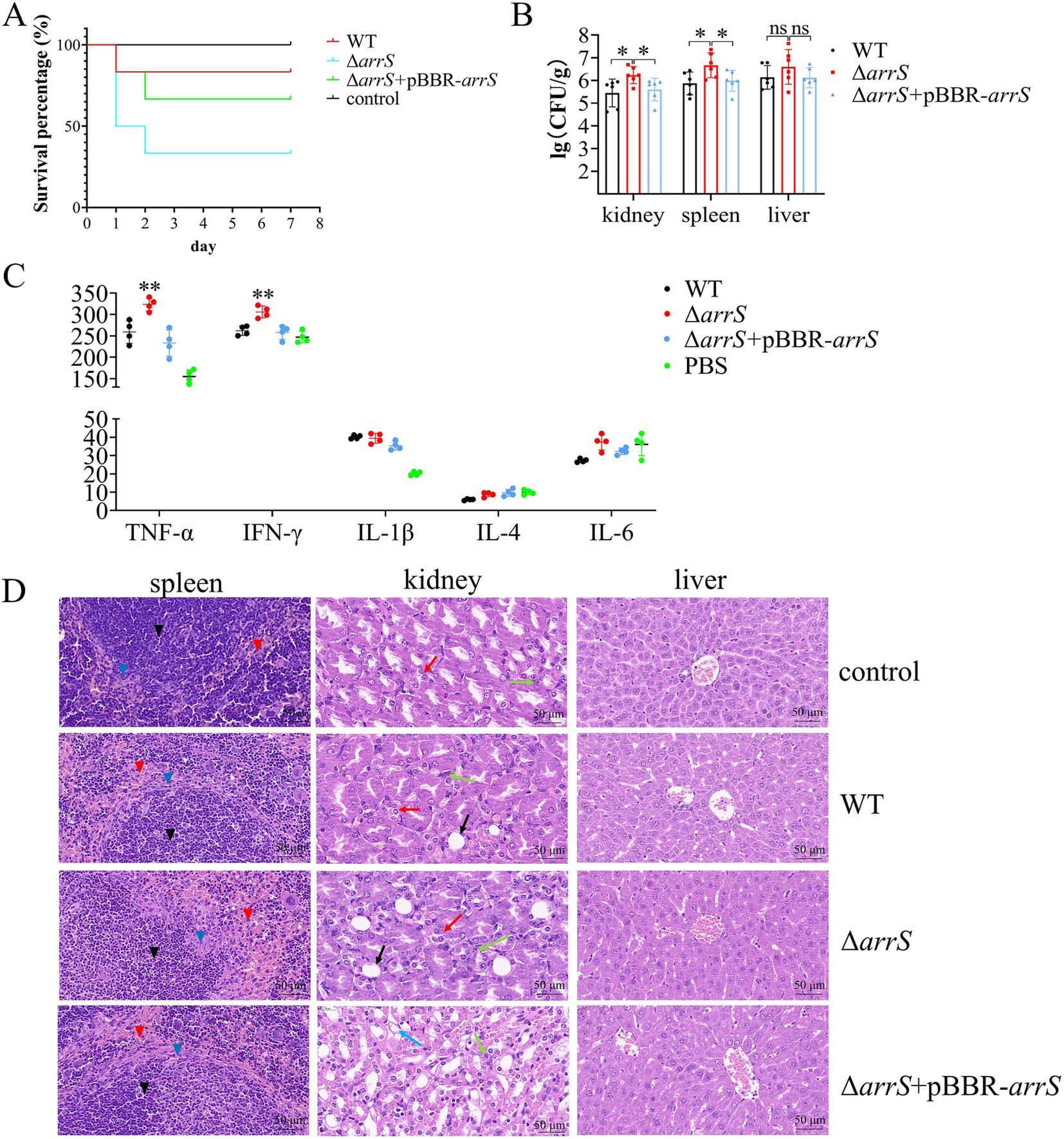

ArrS modulates the virulence of Aeromonas veroniiTCSs associated with c-di-GMP typically play a crucial role in the regulation of virulence in bacteria, such as BvgS from B. pertussis and RocS1 from P. aeruginosa (Dupre et al., 2015a; Sultan et al., 2021). It was postulated that ArrS/ArrR might play a role in the regulation of virulence as well. Therefore, we performed a toxicity assessment of A. veronii in mice. The survival rates within 7 days were recorded and depicted in Figure 4A. At the end of this duration, five mice in the WT group and four mice in the ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS group survived; however, only two mice survived in the ΔarrS group. According to the Mantel-Cox analysis, at an injected dose of 105 CFU/g, the survival rate of mice in the ΔarrS group was significantly lower than the control group (p = 0.0178). In contrast, the WT and the ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS groups did not differ significantly from the control. These results indicated that the knockout of arrS enhanced the pathogenicity of A. veronii.

Figure 4. Involvement of ArrS in the pathogenicity of A. veronii. (A) Survival curve of mice after infection. (B) Assessment of bacterial counts in kidney, spleen and liver. (C) Determination of immune factors via ELISA. (D) Pathological observation of kidney, spleen and liver. Pathological changes were observed with a scale of 50 μm using paraffin sectioning and HE staining. The black, blue, and red inverted triangles represent the white pulp, marginal zone, and red pulp of the spleen, respectively. The black, red, green, and blue arrows represent the renal tubular epithelial cell necrosis, renal tubular atrophy, inflammatory cell infiltration, and vacuolar degeneration of renal tubules of the kidney, respectively. The Experiments were conducted with six replicates in panel (B) and four replicates in panel (C). p-values were obtained from t-tests and the error bars indicate the SD. *denoted significant difference (P<0.05) and **denoted extremely significant difference (P<0.01).

Subsequently, we quantified the numbers of A. veronii in the spleen, liver, and kidney, analyzed the relative levels of immune factors in serum, and conducted hematoxylin–eosin staining and histological examination on these three organs. As depicted in Figure 4B, ΔarrS exhibited the highest abundance in the kidney (2.25 × 106 CFU/g), spleen (8.27 × 106 CFU/g), and liver (1.11 × 107 CFU/g). The abundance of ΔarrS in the kidney and spleen was significantly higher than that of WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS. Although no statistically significant differences were observed in the liver, ΔarrS still demonstrated a comparable increasing trend.

The relative levels of immune factors in serum were illustrated in Figure 4C. Infection with A. veronii triggered immune responses in mice that were mediated by TNF-α and IL-1β. Compared to WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS, ΔarrS specifically induced elevated levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ. This finding corroborated the increased pathogenicity of ΔarrS, and suggested that TNF-α and IFN-γ might be involved in the mechanism by which ΔarrS enhances its pathogenicity.

The HE-stained sections of infected mice were presented in Figure 4D. Following challenge with WT, ΔarrS, or ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS, lesions were observed in the spleen and kidney, while no significant changes were noted in the liver. In the spleen, necrosis and disintegration were observed in the marginal zone of white pulp, accompanied by an expansion of the red pulp and an increase in blood cells and macrophages. In the kidney, the renal tubular epithelial cells in the ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS group exhibited vacuolar degeneration; while in the WT and ΔarrS groups, renal tubular atrophy, significant inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal interstitium, and damage to epithelial cells in the renal tubules were observed. Within the ΔarrS group, a larger necrotic zone was observed at the marginal zone of white pulp in spleens, accompanied by a significant expansion of red pulp; concurrently, increased bubble formation was noted due to the necrosis of glomerular epithelial cells, along with heightened infiltration of inflammatory cells into the renal interstitium, and irregularities observed in renal tubules resulting from severe wrinkling. In comparison to WT and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS, knockout of arrS enhanced the pathogenicity of A. veronii toward the spleen and kidney of mice.

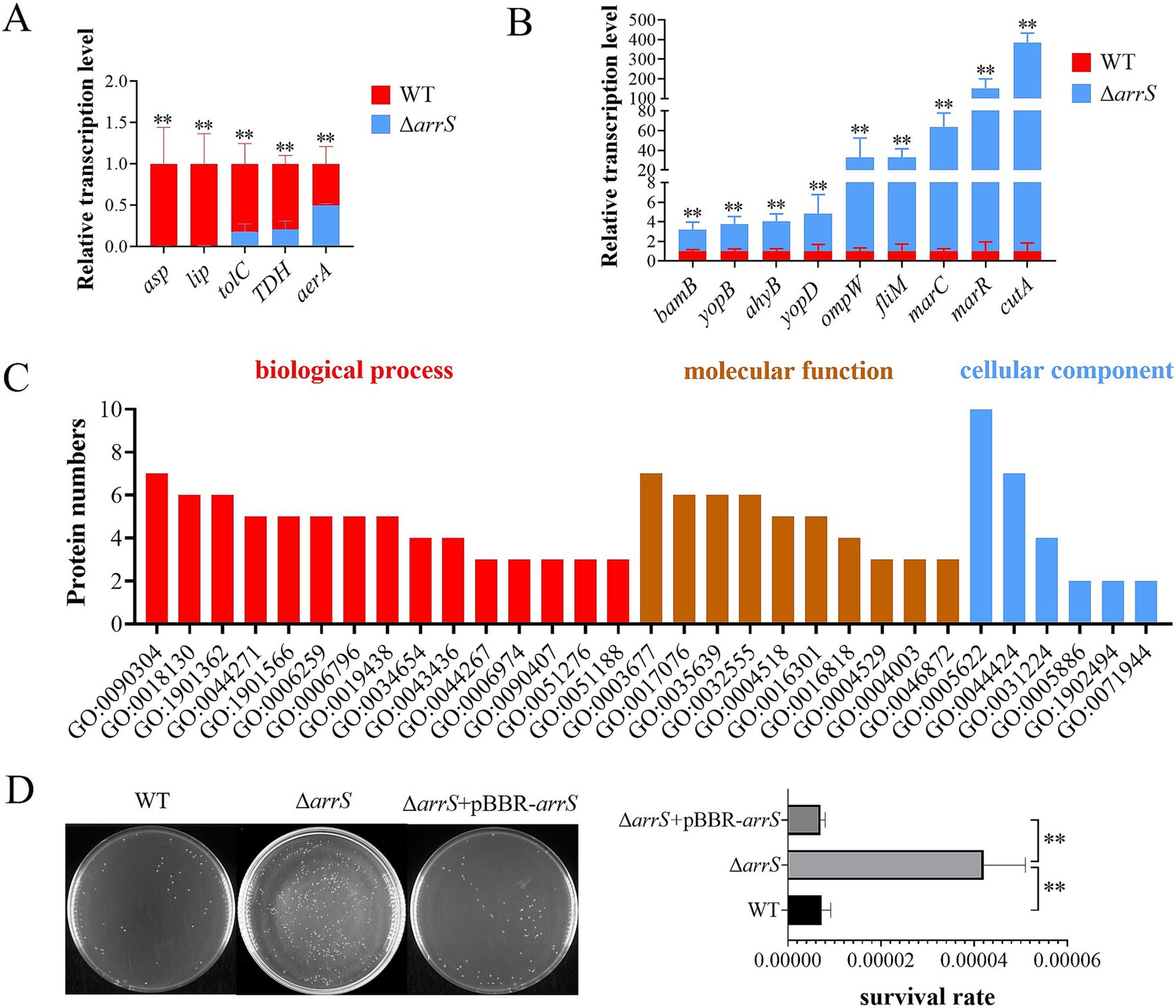

ArrS/ArrR modulates the transcription of genes associated with virulenceA total of twenty virulence-related genes of A. veronii, as previously reported, were analyzed by RT-PCR (Liu et al., 2017). Figures 5A,B illustrated the down-regulated and up-regulated genes in ΔarrS. The identified down-regulated genes are orthologous to the serine protease gene asp, the lipase gene lip, the outer membrane protein gene tolC, the thermostable direct hemolysin gene TDH, and the aerolysin gene aerA, respectively. Conversely, the up-regulated genes identified are orthologous to the outer membrane protein assembly factor gene bamB, the elastase gene ahyB, the type III secretion-related translocators genes yopB and yopD, the outer membrane protein gene ompW, the flagellar motor switch protein gene fliM, the stress protective protein gene marC, the multidrug resistance regulatory protein gene marR, and the bivalent cation tolerance protein gene cutA, respectively. Most of them can influence the host’s inflammatory response directly or indirectly, theoretically enhancing the immunogenicity of A. veronii and inducing severer autoimmune responses in host organisms.

Figure 5. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional effects of arrS knockout in A. veronii. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of virulence associated genes that were down-regulated and (B) up-regulated. (C) Gene ontology annotation. The histogram depicted the differential expressed protein numbers enriched in biological process (level 5), molecular function (level 5), and cellular component term (level 3). (D) Verification of UV radiation tolerance. The survival rate was determined by CFU counting. Experiments were conducted with three replicates in panels (A,B), and five replicates in panel (D). p-values were obtained from t-tests and the error bars indicate the SD. **denoted extremely significant difference (P<0.01).

RecB is a target protein of the ArrS/ArrRThe fluctuation of intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations induced by ArrS/ArrR might influence the protein expression of A. veronii. In order to identify the target proteins of ArrS/ArrR, a proteome analysis was conducted to compare A. veronii WT and ΔarrS in the stationary phase. A total of 2,614 proteins were discovered. Among them, eight differentially expressed proteins were identified, with five up-regulated and three down-regulated in ΔarrS. The exonuclease RecB exhibited the most affected expression in ΔarrS, with a 13.8-fold increase compared to WT. Furthermore, 30 proteins were exclusively detected in ΔarrS, while 14 proteins were found only in WT (including ArrS). Detailed information regarding these differentially expressed proteins was listed in Supplementary Table S3. Subsequently, gene ontology annotation was performed using Blast2GO (v5.2.5), as shown in Figure 5C and Supplementary Table S4. A total of 32 proteins were annotated, and the nucleic acid metabolic process (GO:0090304) and DNA metabolic process (GO:0006259) were the most affected biological processes in A. veronii, involving 7 and 5 proteins, respectively. Notably, both processes included RecB.

RecB is one of the three subunits comprising exonuclease V and plays a crucial role in DNA repair. Consequently, the upregulation of RecB significantly will enhance the tolerance against UV irradiation (Prada Medina et al., 2016). Thus, we compared the UV radiation tolerance among WT, ΔarrS, and ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS, as presented in Figure 5D. Following 1 min irradiation, the survival rate of ΔarrS was found to be 0.0042%, which was approximately 5.84 times higher than that of WT and 5.97 times higher than that of ΔarrS + pBBR-arrS. This finding was consistent with the proteomic data, confirming that RecB was up-regulated in ΔarrS and served as a target protein of ArrR/ArrR. Thus, ArrS/ArrR might modulate the viability of A. veronii through RecB regulation.

DiscussionIn this study, we elucidated a TCS comprising ArrS and ArrR and investigated its function in A. veronii, while identified ArgR as the transcription factor. Notably, the sensor domain of ArrS featured two PBP2 domains. Previous studies have identified temperature, nicotinate, Mg2+, SO42−, and histidine as the potential signaling molecules for PBP2 domains (Xu et al., 2017; Lesne et al., 2018). However, in this study, we were unable to validate the specific signaling molecules recognized by ArrS. Nevertheless, during the UV radiation experiments, we noticed that WT and ΔarrS strains were more likely to exhibit their differences in survival rates when they were undergone prolonged culture and reached high bacterial densities. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, we slightly extended the culture time of A. veronii to increase the likelihood of triggering the function of ArrS/ArrR. For instance, the culture time was set at 18 h for proteomic sample preparation, while it was extended to 21 h for RT-qPCR. This may account for the discrepancy between our proteomic data and RT-qPCR results.

In ArrRm, we replaced the aspartic acid residue that serves as the phosphorylation site of the REC domain with alanine. This approach was commonly used to simulate the dephosphorylated states of SK and RR. Following these mutations, the resulting simulated dephosphorylated conformation of ArrRm might be more conducive to its PDE activity compared to ArrR, leading to a slightly higher PDE activity than that of ArrR (Figure 1C). Although the differences were significant, given that the PDE activity difference between ArrRm and ArrR was less than 2-fold, we suspected that there might not be a substantial difference in their PDE activities; rather, the variation observed in Figure 1C could be attributed to fluctuations in protein expression and purification processes. For example, a fraction of ArrR might undergo phosphorylation during in vivo expression, leading to a reduction in the overall enzymatic activity, whereas ArrRm was less impacted due to its mutation in the phosphorylation site. Additionally, random fluctuations in PDE activity might occur during the processes of protein purification and recovery. Regardless of the existence of differences in PDE activity between ArrR and ArrRm, our conclusion that the PDE activity of ArrR was inhibited by phosphorylation remains unequivocal.

ArrS can inhibit ArrR’s PDE activity by phosphorylating ArrR, theoretically leading to a lower intracellular c-di-GMP concentration in ΔarrS compared to the WT. However, quantitation of intracellular c-di-GMP and observations related to biofilm and motility both indicated a higher intracellular c-di-GMP concentration in ΔarrR. Therefore, what is causing the increase in intracellular c-di-GMP concentration within ΔarrR? We suspect that ArrS may possess phosphatase activity and catalyze the dephosphorylation of ArrR. This conjecture is inspired by the behavior of BvgS: when stimulated at 37°C, BvgS demonstrates kinase activity, leading to the phosphorylation of BvgA; upon binding to nicotinate, BvgS switches to phosphatase activity and facilitates the dephosphorylation of BvgA (Dupre et al., 2015b). Given that ArrS shares similar domains with BvgS, ArrS might also have the potential to become a phosphatase like BvgS does. As previously mentioned, Figure 2F indicated ArrS and ArrR should achieve their functions in a common mechanism. This speculation further aligns well with this condition. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that alternative mechanisms contribute to elevated intracellular c-di-GMP levels in ΔarrS. For instance, according to the proteomic data, A0A160EYR7 and the arginine carboxylate lyase ArgH were found to be upregulated in ΔarrS. A0A160EYR7 has a GGDEF domain at C-terminal and might possess DGC activity, while deletion of ArgH would result in decreased c-di-GMP concentration (Barrientos-Moreno et al., 2020). Both of them possibly contribute to the elevate

留言 (0)