Enterokinase, also known as enteropeptidase, is a proteolytic enzyme secreted by the duodenum. Enterokinase catalyzes the conversion of trypsinogen into active trypsin, which in turn activates other pancreatic zymogens such as chymotrypsinogen and procarboxypeptidases (1). As such, the protein digestion process largely depends on the activity of enterokinase. Enterokinase deficiency (EKD, OMIM #226200) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease caused by mutations in the transmembrane protease serine 15 (TMPRSS15) gene. EKD in children is characterized by chronic diarrhea, hypoproteinemia, anemia, and failure to thrive. Fortunately, the prognosis of EKD is good provided that an early diagnosis is achieved, allowing appropriate enzyme supplementation. The first case of EKD was reported by Hadorn et al. in 1969 (2). However, in the intervening decades, only 13 cases have been reported (2–15) (Table 1). Herein, we report a case of EKD with novel compound heterozygous mutations in TMPRSS15 (c.2611C>T; c.1584_1585insCTTT).

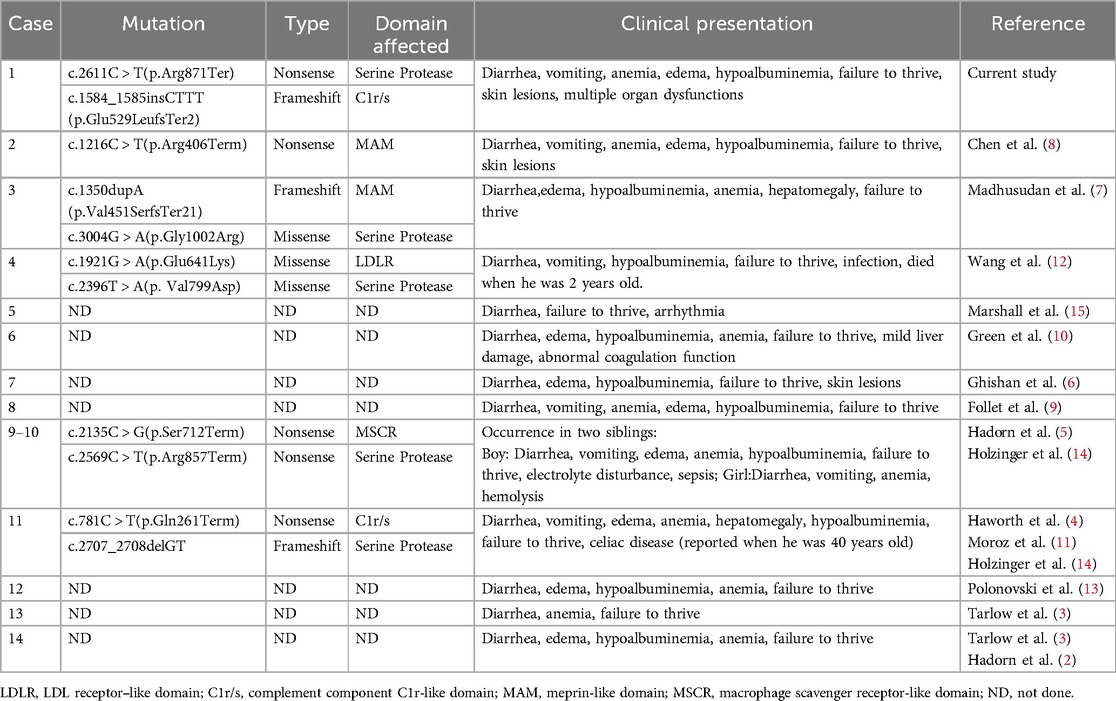

Table 1. Summary of reported cases of enterokinase deficiency.

2 Case presentationA 2-month-old female infant was admitted to hospital due to pallor and edema lasting 6 days. She also experienced a slight cough, rash, diarrhea, and occasional vomiting. Diarrhea was described as the passage of loose green stools seven to eight times per day, at 1 month of age. The infant was born at term and weighed 4.15 kg, and was consistently breastfed after birth. Her parents were healthy non-consanguineous Chinese adults, and the patient had no relevant family history. On examination, the infant weighed 4.9 kg, indicating a weight gain of only 0.75 kg in the first 2 months of life. The patient was pale and puffy, with generalized edema. Hazel rashes, erosions, and crusts were observed on the neck and lower extremities.

The initial laboratory investigations revealed anemia (Hb 51 g/L), hypoalbuminemia (Alb 16.4 g/L), coagulation abnormalities (PT 94.40s, APTT 82.70s, TT 54.20s, Fib 0.24 g/L, D-Di 0.19 mg/L), myocardial damage (CK-MB 26.02 ng/ml, CK 1117U/L, LDH 403U/L, AST 129U/L), and renal dysfunction (Cr 36 μmol/L). Her reticulocyte and bilirubin levels were also slightly elevated (Ret 5.32%, TBIL 19.8 μmol/L, DBIL 11.6 μmol/L, IBIL normal). Coombs test results were negative. Her white blood cell (WBC) count was 12.28 × 109/L, with 57.2% neutrophils and 40.2% lymphocytes, while her platelet (PLT) count was 101 × 109/L. The serum procalcitonin and ferritin levels were increased (PCT 1.86 ng/ml, Ferr 1020 μg/L). Further, her complement C3 level was decreased to 0.359 g/L, whereas that of C4 was normal. Here C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation (ESR), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), antinuclear antibody (ANA), IgA, IgG, IgM, K+, Na+, and Cl- concentrations were all within the normal range. Stool microscopy and fecal calprotectin levels revealed no abnormalities. Urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPCR) was >0.2, while multiple urinalysis and microalbuminuria were normal, which may be related to the low urinary creatinine excretion rate, contributing to the overestimation of UPCR (16). Ultrasound (US) revealed echogenicity of the liver parenchyma; however, US images of the gallbladder, pancreas, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract all appeared normal. Cardiac ultrasonography indicated patent foramen ovale and a normal ejection fraction. Computed tomography further revealed fatty infiltration in the liver, with no abnormal changes in the lungs. Brain MRI was normal.

After admission, the patient underwent surveillance with ECG-monitoring, and was treated with antibiotics, intravenous albumin, fresh frozen plasma, fibrinogen preparation, and red blood cell transfusions. Meanwhile, the patient was started on a new feeding regimen with a deep-hydrolyzed formula. On the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient's myocardial zymogram and creatinine levels returned to normal, and coagulation function gradually improved. However, diarrhea and vomiting were not alleviated. Regarding skin lesions, following consultation with attending neonatologists and dermatologists, the patients was suspected to have incontinentia pigmenti (PI) as the linear erythema, with erosion, exudation and crust on the extremities (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Erythema, with erosion, exudation and crust on the extremities.

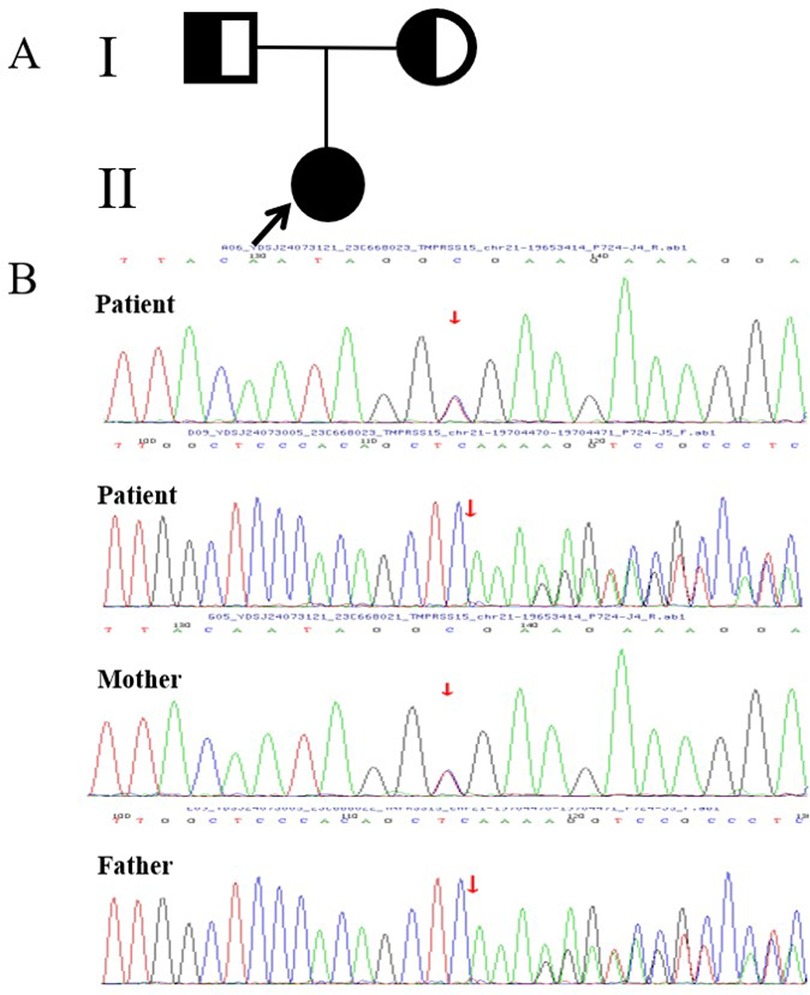

Based on the above results, we ruled out nephrotic syndrome, serious liver dysfunction, heart failure, chronic infection, malignant tumor, intestinal lymphangiectasia and connective tissue disease as potential diagnoses. However, PI, congenital diarrhea, immune deficiency were retained for consideration. Gastrointestinal endoscopy was recommended to further clarify the patient's etiology; however, her parents refused. Given the patient's sever presentation and broad differential diagnosis, peripheral blood samples were collected from the patient and her family members to perform whole-exome sequencing (WES) after obtaining written consent from the parents. The results showed that the patient had two novel compound heterozygous mutations in exons 22 [c.2611C > T (p.Arg871Ter)] and 14 [c.1584_1585insCTTT (p.Glu529LeufsTer2)] of the TMRRSS15 gene (Figure 2). Sanger sequencing confirmed that the variants were inherited from her parents. Her mother carried the c.2611C > T mutation and her father carried the c.1584_1585insCTTT mutation. According to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines for variant classification, c.2611C > T and c.1584_1585insCTTT were classified as “likely pathogenic” variants. Evidence, including PVS1 (null variant) and PM2 (extremely low frequency in the population databases), is presented to support this classification.

Figure 2. (A) The proband's family tree diagram; the arrow indicates the proband. The circles represent the proband and her mother, and the square represents her father. (B) Sanger sequencing diagram. The mutation was verified by Sanger sequencing, which revealed two novel compound heterozygous mutations in exons 22 [c.2611C > T (p.Arg871Ter)] and 14 [c.1584-1585insCTTT (p.Glu529LeufsTer2)] of TMRRSS15 gene, which were inherited from the patient's mother and father, respectively.

Ultimately, the patient was diagnosed with EKD based on her clinical characteristics and genetic testing results. Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy was performed immediately following a definitive diagnosis of EKD, resulting in dramatic improvements in diarrhea, vomiting, malnutrition, and skin lesions. The patient was subsequently fed on a deep-hydrolyzed formula, and continued to receive pancreatic enzyme supplementation. After a one year of treatment, the infant showed a normal rate of physical development, with no recurrence of anemia, hypoproteinemia, coagulopathy, or skin lesions.

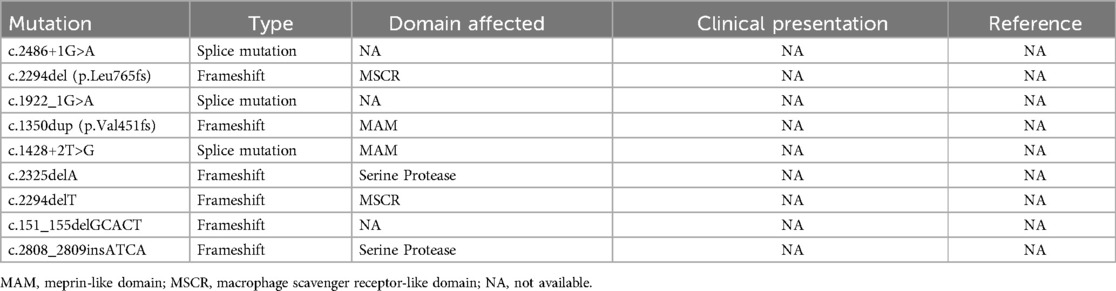

3 DiscussionEnterokinase deficiency (EKD,OMIM #226200) is an extremely rare autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the TMPRSS15 gene (14), which is located on chromosome 21q21.1, and contains 25 exons (17, 18). To date, only twelve pathogenic variations have been described in the human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®) and four in ClinVar (Tables 1, 2). Reported mutation types predominantly include nonsense and frameshift mutations. This gene encodes enterokinase, a serine protease secreted by the intestinal brush border. As a physiological activator, enterokinase first converts trypsinogen into active trypsin in the duodenum. Trypsin subsequently activates other proteolytic enzymes and the remaining trypsinogens. Aberrations in TMPRSS15 gene expression may result in a reduction or the abolition of the enzymatic function of enterokinase, leading to severe disturbances in protein digestion. In this case, the patient had two novel compound heterozygous mutations in exons 22 [c.2611C > T (p.Arg871Ter)] and 14 [c.1584_1585insCTTT (p.Glu529LeufsTer2)] of TMRRSS15, which resulted in the premature termination of Arg871 in the serine protease domain, and a frameshift of amino acids in the complement component C1r-like domain (C1/rs). Loss-of-function mutations in TMRRSS15 produce the EKD phenotype.

Table 2. Summary of other unreported mutations from HGMD and clinVar.

Children with EKD typically develop symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, anemia, hypoproteinemia and undergrowth (2–13, 15), which was consistent with the presentation of our patient. Previous reports have elucidated the mechanisms underlying these conditions. The finding of diarrhea was likely attributable to secondary decreased activities of digestive enzymes, such as lipase, amylase, and disaccharidase (3, 5). Owing to general protein malabsorption, the patient subsequently presented with hypoalbuminemia and systemic protein loss. Anemia likely occurred due to impaired hemoglobin synthesis caused by protein deficiency. The observed hemolysis may be related to vitamin E deficiency (5, 10). The manifestation of fatty liver infiltration developed secondary to protein-energy malnutrition, which is similar to the phenotype observed in patients with severe malnutrition and kwashiorkor (4). In addition, coagulopathy with prolonged PT and APTT was likely caused by inadequate coagulation factors synthesis.

Skin lesions have been previously described in two cases: one with eczema around the perioral and diaper areas (6) and another with acrodermatitis enteropathica-like lesions (8). Our patient further developed skin damage, indicating that skin manifestations are likely to be a novel EKD phenotype. We initially considered a diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare X-linked dominant neuroectodermal disorder primarily caused by mutations in the IKBKG/NEMO gene, which may be associated with immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, Behcet syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, etc.) (19–22). However, unlike IP, the patient's skin lesions did not following the four typical stages (erythema and vesicles, verrucous hyperplasia, hyperpigmentation, and atrophy), and was significantly improved after treatment with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy. Furthermore, we found no abnormalities in the patient's neuroectodermal tissues, including the eyes, hair, teeth, and nails, or the central nervous system. Further, no pathogenic genetic variants that led to other illnesses were detected. Consequently, the diagnosis of IP was ruled out. In fact, skin manifestations could be seen in a variety of nutritional diseases, including cystic fibrosis and essential fatty acids deficiency, among others. In EKD, skin lesions may develop as a result of an interaction between proteins, microelements, and essential fatty acid deficiencies secondary to malabsorption.

Our patient also presented with multiple organ dysfunctions, including transient abnormalities in renal function, myocardial injury, and coagulation disturbances, which may be explained by infection, which has been reported to worsen EKD. Wang et al. (12). previously reported the case of a patient with EKD who developed intestinal and pulmonary infections during hospitalization, subsequently dying from this illness 2 weeks after suspending treatment. Nutrient malabsorption may contribute to immunocompromization, increasing the risk of infection and mortality. In the present case, multi-organ damage gradually improved following anti-infective therapy.

EKD is considered treatable. Enzyme replacement therapy greatly improves the prognosis of EKD, allowing patients to grow without obvious symptoms, sometimes even without enzyme supplementation. However, if treatment is delayed, patients may suffer from the severe long-term effects of malnutrition. In the past, EKD was diagnosed by assaying the enzymatic activity of the duodenal juice using the zymogen activation test (2). However, in practice, some families can be hesitant about the invasive procedure, particularly in infants. With the further in-depth study of the genetic mechanisms of the disease, genetic analysis can help to facilitate the early diagnosis of clinically clear single-gene genetic diseases, such as EKD, trypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, etc. This case indicates that EKD should be included in the differential diagnosis of children with clinical symptoms, such as chronic diarrhea, hypoproteinemia and failure to thrive, with no improvement following conventional treatment. In this case, although zymogen activation tests and endoscopy were not performed, the patient was diagnosed with EKD by WES, and showed dramatic improvements in symptoms and general health with enzyme supplementation. During the one-year follow-up, the patient showed a normal rate of physical development, with no recurrence of skin lesions or multisymptom damage.

4 ConclusionOverall, in this report, we describe a patient with EKD with two novel compound heterozygous mutations in TMPRSS15 who achieved dramatic improvements in symptoms with pancreatic enzyme supplements. This case enriches the genotypic spectrum of EKD, and provides a reference for diagnosis and treatment. If zymogen activation testing is not possible, genetic analysis may be an effective tool to facilitate early diagnosis. Early pancreatic enzyme supplementation is a clinically substantial factor influencing satisfactory outcomes.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Children's Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsYL: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal Analysis. RL: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis. YP: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. XW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. LD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. XL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Science and Technology Project of Jinan Municipal Health Commission No. 2023-2-145.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References3. Tarlow MJ, Hadorn B, Arthurton MW, Lloyd JK. Intestinal enterokinase deficiency. A newly-recognized disorder of protein digestion. Arch Dis Child. (1970) 45:651–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.243.651

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Haworth JC, Gourley B, Hadorn B, Sumida C. Malabsorption and growth failure due to intestinal enterokinase deficiency. J Pediatr. (1971) 78:481–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(71)80231-7

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Hadorn B, Haworth JC, Gourley B, Prasad A, Troesch V. Intestinal enterokinase deficiency. Occurrence in two sibs and age dependency of clinical expression. Arch Dis Child. (1975) 50:277–82. doi: 10.1136/adc.50.4.277

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Ghishan FK, Lee PC, Lebenthal E, Johnson P, Bradley CA, Greene HL. Isolated congenital enterokinase deficiency. Recent findings and review of the literature. Gastroenterology. (1983) 85:727–31. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(83)90033-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Chen Y, Li Z, Liu C, Wang S. Enterokinase deficiency with novel TMPRSS15 gene mutation masquerading as acrodermatitis enteropathica. Pediatr Dermatol. (2023) 40:389–91. doi: 10.1111/pde.15197

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Moroz SP, Hadorn B, Rossi TM, Haworth JC. Celiac disease in a patient with a congenital deficiency of intestinal enteropeptidase. Am J Gastroenterol. (2001) 96:2251–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03970.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Wang L, Zhang D, Fan C, Zhou X, Liu Z, Zheng B, et al. Novel compound heterozygous TMPRSS15 gene variants cause enterokinase deficiency. Front Genet. (2020) 11:538778. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.538778

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Polonovski C, Laplane R, Alison F, Navarro J. Pseudo-déficit en trypsinogène par déficit congénital en enterokinase. Etude clinique [trypsinogen pseudo-deficiency caused by congenital enterokinase deficiency. Clinical study]. Arch Fr Pediatr. (1970) 27:677–88.5488678

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

14. Holzinger A, Maier EM, Bück C, Mayerhofer PU, Kappler M, Haworth JC, et al. Mutations in the proenteropeptidase gene are the molecular cause of congenital enteropeptidase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. (2002) 70:20–5. doi: 10.1086/338456

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Marshall G, Mitchell JD, Tobias V, Messina IM. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia in a child with congenital enteropeptidase deficiency and hypogammaglobulinaemia. Aust Paediatr J. (1989) 25:106–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1989.tb01429.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Chen CF, Yang WC, Yang CY, Li SY, Ou SM, Chen YT, et al. Urinary protein/creatinine ratio weighted by estimated urinary creatinine improves the accuracy of predicting daily proteinuria. Am J Med Sci. (2015) 349:477–87. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000488

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Kitamoto Y, Yuan X, Wu Q, McCourt DW, Sadler JE. Enterokinase, the initiator of intestinal digestion, is a mosaic protease composed of a distinctive assortment of domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1994) 91:7588–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7588

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Kitamoto Y, Veile RA, Donis-Keller H, Sadler JE. cDNA sequence and chromosomal localization of human enterokinase, the proteolytic activator of trypsinogen. Biochemistry. (1995) 34:4562–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. How KN, Leong HJY, Pramono ZAD, Leong KF, Lai ZW, Yap WH. Uncovering incontinentia pigmenti: from DNA sequence to pathophysiology. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:900606. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.900606

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Eigemann J, Janda A, Schuetz C, Lee-Kirsch MA, Schulz A, Hoenig M, et al. Non-Skewed X-inactivation results in NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) Δ-exon 5-autoinflammatory syndrome (NEMO-NDAS) in a female with incontinentia Pigmenti. J Clin Immunol. (2024) 45:1. doi: 10.1007/s10875-024-01799-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Juan CK, Shen JL, Yang CS, Liu KL, Chen YJ. Flare-up of incontinentia pigmenti in association with behçet disease. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2015) 13:154–6. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12452

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Piccoli GB, Attini R, Vigotti FN, Naretto C, Fassio F, Randone O, et al. NEMO Syndrome (incontinentia pigmenti) and systemic lupus erythematosus: a new disease association. Lupus. (2012) 21:675–81. doi: 10.1177/0961203311433140

留言 (0)