Injectable GnRH receptor agonists have been shown to improve cancer control when combined with radiotherapy (RT) (1). Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in conjunction with conventionally fractionated radiation therapy significantly improves metastases-free and overall survival in men with prostate cancer (2). As with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), early data suggests that the addition of ADT to SBRT for unfavorable prostate cancer may also reduce local persistence of disease and biochemical recurrence (3, 4). Unfortunately, ADT combined with RT remains underutilized, possibly due to bothersome persistent side effects and its potentially negative impact on cardiovascular comorbidities (5).

Relugolix is an oral ADT that suppresses gonadotropic release from the pituitary gland, thus decreasing concentrations of testosterone (6). The HERO study investigated the efficacy of this oral GnRH receptor antagonist compared to GnRH agonist leuprolide. The randomized Phase 3 trial demonstrated the superiority of relugolix in achieving and maintaining castration (7). Men treated with relugolix maintained castration through 48 weeks at a rate of 96.7% compared to 88.8% with leuprolide (7). The study exhibited a 99% adherence rate with oral relugolix, although most patients had daily audible reminders to take their pill (7). Similarly, neoadjuvant/adjuvant relugolix (6 months) has been studied in unfavorable localized prostate cancer in combination with conventionally fractionated radiation therapy (79.2 Gy in 44 fractions) (8). With relugolix, 95% achieved castration (total testosterone < 50 ng/dL, 1.73 nmol/L) and 82% reached profound castration (total testosterone < 20 ng/dL; 0.7 nmol/L). As with the HERO study, interventions to improve adherence were utilized (8).

While oral ADTs have potential advantages, their real-world effectiveness is dependent on patient adherence (9). Non-adherence to ADT could lead to increased rates of biochemical recurrence and prostate cancer-specific death. Adherence is defined as taking a medication exactly as prescribed. Generally, an adherence rate of > 80% is required for optimal therapeutic efficacy. Unfortunately, medication non-adherence is common, with up to 50% of patients self-reporting non-adherence (10). The estimated rate of non-adherence in prostate cancer patients receiving oral anti-androgens for metastatic disease is 5-10% (11–14). Factors associated with non-adherence include advanced age, multiple daily doses, side-effect severity, length of use, and inadequate patient education (15). Bothersome side effects such as hot flashes, fatigue, and decreased libido may lead to drug holidays and/or early cessation (16). This may be a bigger problem in minority and other underserved populations (15, 16).

Currently, a test for relugolix serum levels is not clinically available. However, adherence can be measured using indirect methods (i.e., serum testosterone levels) or subjective measures, such as patient-reported outcomes (PROs). PROs allow for early assessment that is both affordable and non-invasive. The Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ) is a commonly used psychometrically validated questionnaire with six questions to quantify omissions and barriers to adherence (forgetfulness, carelessness, skipping doses due to adverse side effects) (17, 18). This information can be utilized to develop individualized approaches tailored to a patient’s specific reasons for and level of non-adherence.

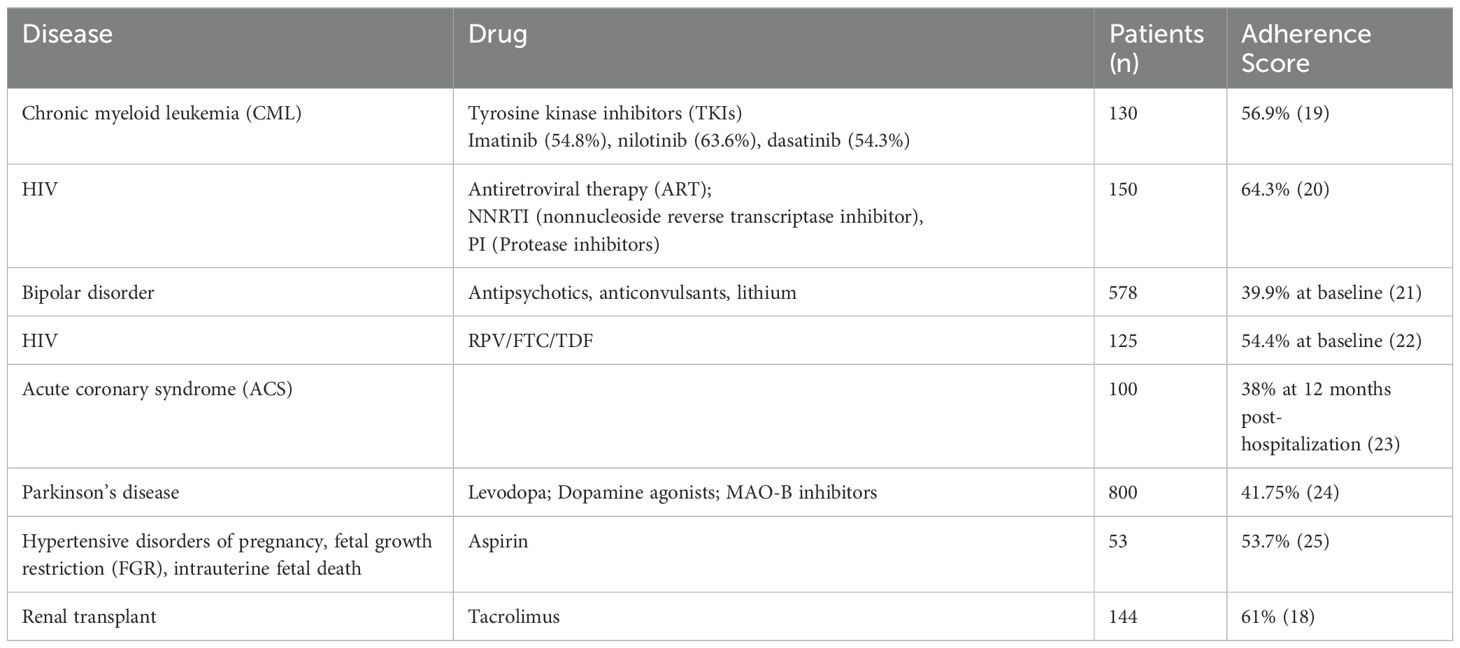

Adherence to medications assessed by SMAQ has been studied for a variety of medications utilized in different disease states, such as chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), HIV, bipolar disorder, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), Parkinson’s disease, and more (18–25). These studies have identified numerous predictive factors of SMAQ-reported adherence, including patient education level, employment status, cognitive functioning, alcohol consumption, and negative attitude toward treatment (19–21). However, other studies utilizing the SMAQ have found no correlation between compliance and social demographic data (23, 25). Additionally, adherence to therapy has been shown to be affected by treatment-related toxicities and patient quality of life (22).

Limited data are available on patient adherence to oral ADT in men receiving radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Further knowledge in this area would aid in developing approaches to improve adherence. The objective of this study was to prospectively collect and report patient-reported relugolix adherence at the start of prostate SBRT for intermediate to high-risk prostate cancer. In addition, we demonstrate the feasibility of incorporating the SMAQ into daily clinical practice during a course of RT and its utility in improving drug adherence.

Materials and methodsWe conducted an IRB-approved, prospective study (IRB 12-1175) of men with prostate cancer treated with short-term relugolix and prostate SBRT at Georgetown University Hospital. Patient and treatment characteristics, such as age, race, partner status, comorbidities, BMI, and risk group, were acquired from the medical records.

Drug treatmentRelugolix was initiated with a loading dose of 360 mg on the first day and continued treatment with a 120 mg dose taken orally once daily at approximately the same time each day. If a dose was missed, and it was 12 hours or less since they were supposed to take their pill, patients were instructed to take the pill as soon as they remembered. If the dose was missed by more than 12 hours, patients were instructed not to take the missed dose and to take their next dose at the regular time the next day. Patients were informed that they would take the pills for approximately three to six months and at the end of this period, they would discontinue the medication, with expected rapid testosterone recovery and side effect resolution (7). Relugolix treatment duration varied within the patient cohort due to heterogeneity in the timing of initiating prostate SBRT. SBRT was delayed due to logistical challenges, including patient availability, fiducial placement scheduling, and treatment planning MRI availability.

SBRT treatment planning and deliveryProstate SBRT was delivered using the CyberKnife robotic radiosurgical system (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) as previously described (26, 27). Approximately two months following the initiation of relugolix, gold fiducials were transperineally placed into the prostate. One week after fiducial placement, CT and high-resolution MR images were obtained for treatment planning. In general, patients initiated prostate SBRT 2-4 weeks following treatment simulation. Radiation was delivered every other day in 5 approximately 35-minute treatments.

Follow-up and assessmentPRO assessments were prospectively collected at the first doctor visit after the initiation of relugolix. Total testosterone levels were collected at the time of questionnaire administration. We defined both effective and profound castration as serum testosterone of <50 ng/dL (¾1.73 nmol/L) and ¾ 20 ng/dL (¾0.7 nmol/L), respectively, as previously described (7). The SMAQ is a validated tool that measures drug adherence (18). A patient is considered non-compliant via the SMAQ if he responds to any question with a non-adherent answer or has missed two or more doses in the last week or two consecutive days since the last healthcare visit. Patients were grouped into adherent and non-adherent populations based on these criteria. To compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who adhered to treatment versus those who did not, t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test were used. A p-value < 0.05 determined statistical significance.

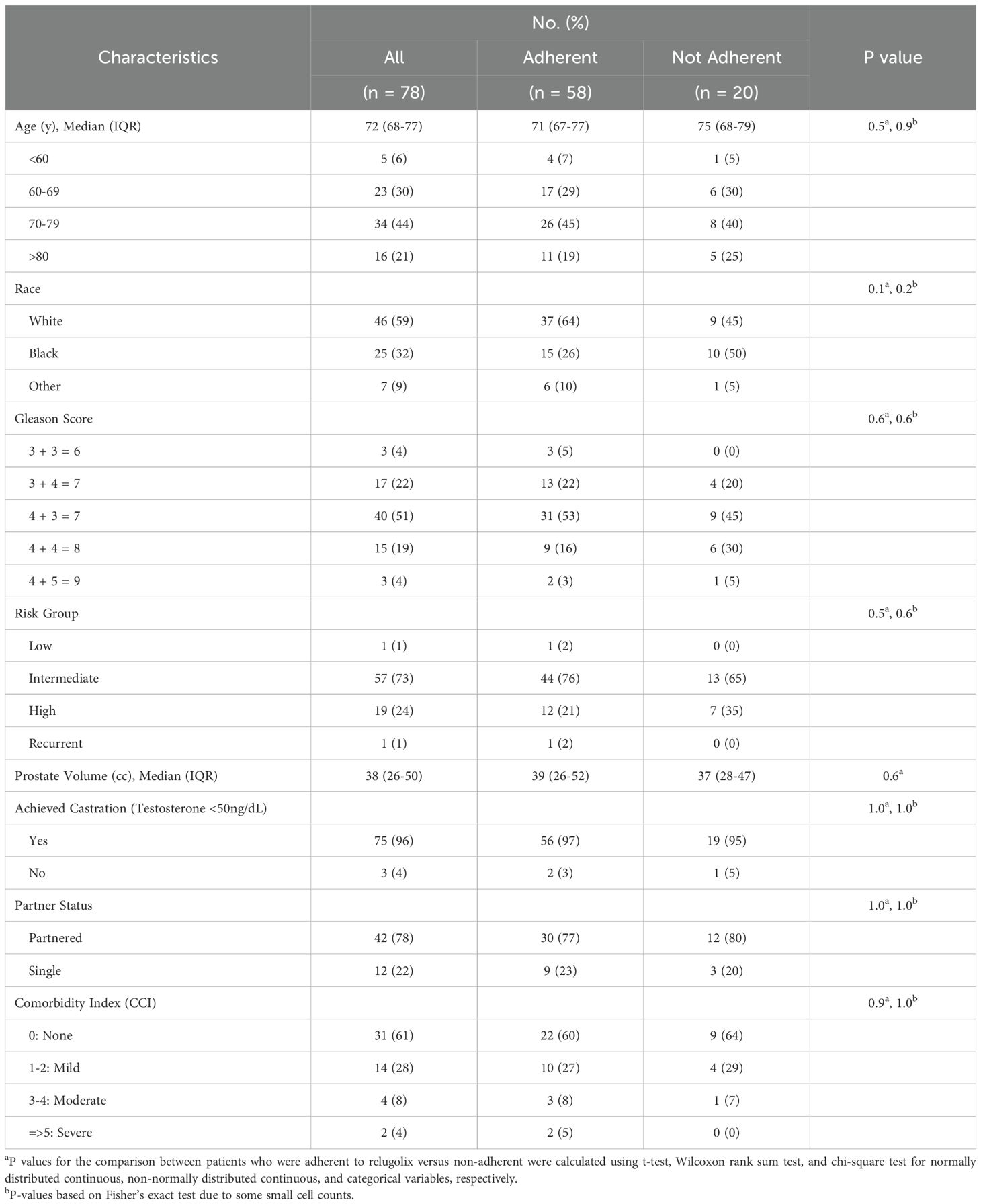

ResultsPatient, treatment, and tumor characteristicsBetween August 2021 and December 2023, 78 men were treated at Georgetown with relugolix and prostate SBRT per an institutional protocol. The median age was 72, 41% of patients were non-white, 22% were un-partnered, and 12% had a moderate to severe comorbidity index (Table 1). Patients initiated relugolix at a median of 4 months prior to the SMAQ (range of 2-19 months).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics.

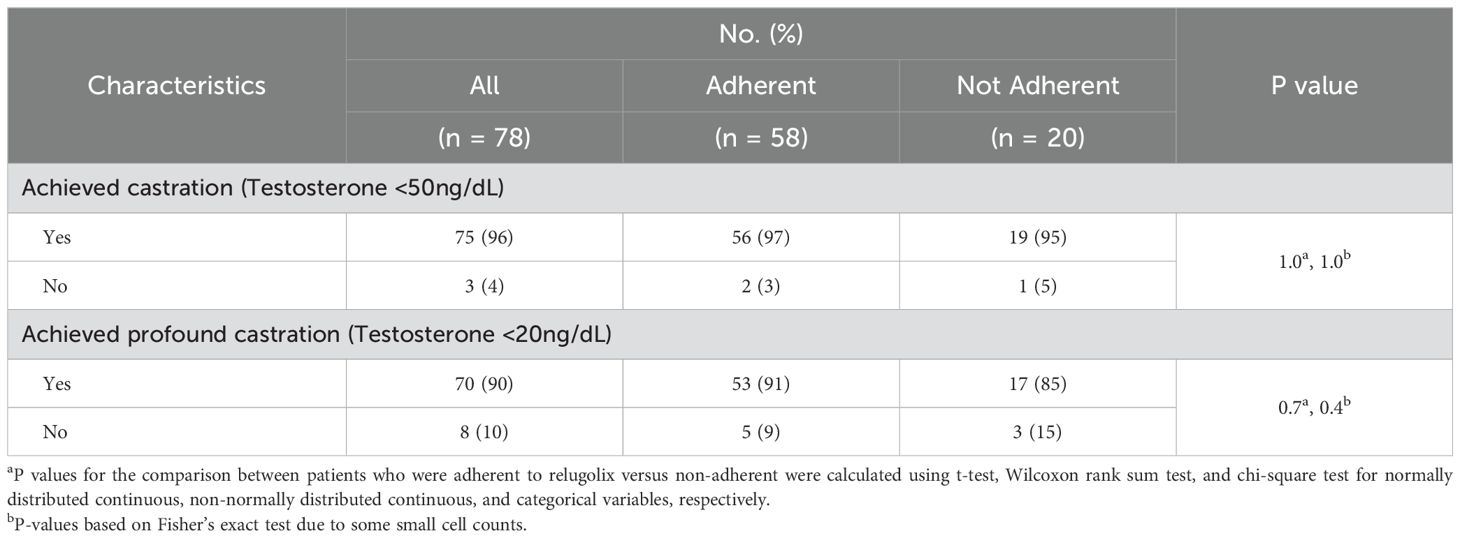

Total testosterone levelsSee Table 2 for a summary of testosterone responses following relugolix. At the time of questionnaire administration, 96% of patients achieved a testosterone level ≤50 ng/dl (effective castration) while 90% reached testosterone ≤20 ng/dl (profound castration).

Table 2. Testosterone levels.

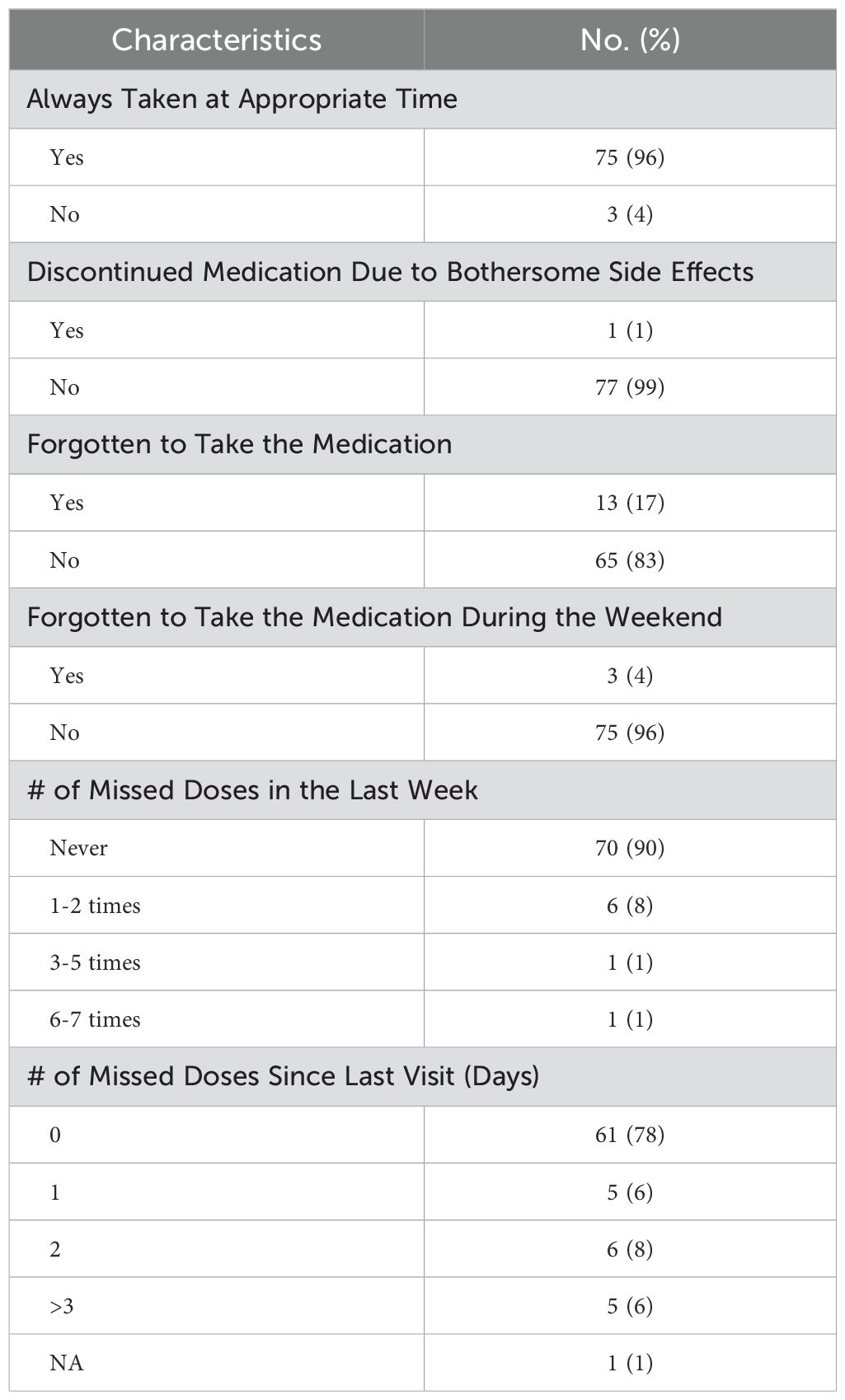

Patient-reported adherence96% of patients achieved castration (≤ 50 ng/dL) at the time of the SMAQ. 96% of men reported always taking relugolix at the appropriate time. 1% discontinued medication due to bothersome side effects, 17% reported forgetting to take the medication, and 4% reported missing a dose during the weekend. 98% and 93% did not miss a dose more than 2 times in the last week and since the last visit, respectively. Overall patient-reported drug adherence was 75% (Table 3). No patient demographic or clinical characteristic predicted non-adherence.

Table 3. Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ) results.

DiscussionThis study utilizes a regimen combining an oral GnRH receptor antagonist, relugolix, and SBRT for localized prostate cancer. Hypofractionated and ultrahypofractionated radiotherapy (SBRT) has been shown to be an effective curative treatment option for patients with localized prostate cancer when compared to conventionally fractioned radiation therapy (CFRT), with favorable biochemical control and toxicity levels (28, 29). ADT can be utilized as a complementary treatment to SBRT, as studies have shown that a combination of the two modalities can provide improved outcomes (3, 4).

Drug adherence is an important consideration when utilizing oral androgen deprivation therapies in combination with prostate SBRT. Measuring serum testosterone levels is a commonly employed indirect measure to assess drug adherence (30). However, interval testosterone levels may not capture short-term drug interruptions that could negatively impact cancer control. A better understanding of patient adherence patterns would aid in designing approaches to improve it.

Prior studies of relugolix utilized daily reminders which likely improved compliance rates and ensured continued testosterone suppression (7, 8). Due to administrative burden, we did not utilize scheduled cues as part of our study. Nonetheless, our self-reported adherence (SMAQ) was medium (60-80%) and higher than previous studies utilizing the SMAQ questionnaire (Table 4; 38-64%). Over 95% of patients reported taking the drug at the same time every day. It was reassuring that only 3% of patients skipped the medication due to bothersome side effects. The main reason for non-adherence was forgetfulness. However, the 20% of men who reported forgetting to take the medication is relatively low for an elderly male patient population (31). The results are reassuring, considering greater than a third of our patients were minorities, 22% were un-partnered and 12% had a moderate to severe comorbidity index (Table 1).

Table 4. Medication adherence assessed by Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ) in varying disease states.

Limitations of our investigation are secondary to its small size and variations in treatment scheduling. Although we aimed to treat all patients with relugolix for a total of 4-6 months with initiation 2 months prior to SBRT, there was heterogeneity in the timing of initiating prostate SBRT. Due to the small sample size, we did not examine whether there were differences in outcomes depending on the timeliness of SBRT. We employed a short course of administration, and adherence may not be as high with a long course (21, 24). Additionally, the SMAQ is not validated for hormonal agents, and the SMAQ did not assess medication concerns associated with non-adherence (i.e., necessity, harmfulness, etc.). Due to high levels of castration, we could not definitively correlate results with an objective measure of adherence.

ConclusionRelugolix allows for high rates of castration and drug adherence when combined with SBRT. Monitoring drug adherence during treatment may allow for prompt detection of non-adherence and timely intervention. Future studies should focus on how to optimally incorporate the SMAQ into patient management.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Georgetown MedStar Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsKG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MJungK: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MJiK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. RC: Writing – original draft, Data curation. SE: Writing – original draft, Data curation. ZZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation. MD: Writing – original draft. AZ: Writing – original draft. MF: Writing – original draft. DK: Writing – original draft. PL: Writing – original draft. ND: Writing – original draft. SS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. SC: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestSC served as a clinical consultant to Accuray, Inc., BlueEarth Diagnostics, Pfizer, and Sumitomo Pharma America, Inc during the the time research was conducted. MF served as a director at Myovant Sciences during the time that research was conducted. The Department of Radiation Medicine at Georgetown University Hospital receives a grant from Accuray to support a research coordinator. MF was employed by Novartis.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References2. Kishan AU, Sun Y, Hartman H, Pisansky TM, Bolla M, Neven A, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use and duration with definitive radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:304–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00705-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Gorovets D, Wibmer AG, Moore A, Lobaugh S, Zhang Z, Kollmeier M, et al. Local failure after prostate SBRT predominantly occurs in the PI-RADS 4 or 5 dominant intraprostatic lesion. Eur Urol Oncol. (2023) 6:275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2022.02.005

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Van Dams R, Jiang NY, Fuller DB, Loblaw A, Jiang T, Katz AJ, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for high-risk localized carcinoma of the prostate (SHARP) consortium: analysis of 344 prospectively treated patients. Int J Radiat OncologyBiologyPhysics. (2021) 110:731–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.01.016

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Falchook AD, Basak R, Chen RC. Androgen deprivation therapy and dose-escalated radiotherapy for intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer—Reply. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:281. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3974

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Shore ND, Saad F, Cookson MS, George DJ, Saltzstein DR, Tutrone R, et al. Oral relugolix for androgen-deprivation therapy in advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:2187–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004325

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Dearnaley DP, Saltzstein DR, Sylvester JE, Karsh L, Mehlhaff BA, Pieczonka C, et al. The oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist relugolix as neoadjuvant/adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy to external beam radiotherapy in patients with localised intermediate-risk prostate cancer: A randomised, open-label, parallel-group phase 2 trial. Eur Urology. (2020) 78:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Sachdev S, Zhang H, Hussain M. Relugolix: early promise for a novel oral androgen deprivation therapy with radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urology. (2020) 78:193–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.053

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Nguyen TMU, Caze AL, Cottrell N. What are validated self-report adherence scales really measuring? A systematic review: Systematic review on validated medication adherence measurement scales. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2014) 77:427–45. doi: 10.1111/bcp.2014.77.issue-3

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Grundmark B, Garmo H, Zethelius B, Stattin P, Lambe M, Holmberg L. Anti-androgen prescribing patterns, patient treatment adherence and influencing factors; results from the nationwide PCBaSe Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2012) 68:1619–30. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1290-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Boegemann M, Khaksar S, Bera G, Birtle A, Dopchie C, Dourthe LM, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for the Management of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) without prior use of chemotherapy: report from a large, international, real-world retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. (2019) 19:60. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5280-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Behl AS, Ellis LA, Pilon D, Xiao Y, Lefebvre P. Medication adherence, treatment patterns, and dose reduction in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving abiraterone acetate or enzalutamide. Am Health Drug Benefits. (2017) 10:296–303.

14. Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille MH, Kamstra R, Emond B, Lefebvre P, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. (2017) 39:1972–85.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.08.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. JCO. (2010) 28:4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Wassermann J, Gelber SI, Rosenberg SM, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Schapira L, et al. Nonadherent behaviors among young women on adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Cancer. (2019) 125:3266–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.v125.18

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Knobel H, Alonso J, Casado JL, Collazos J, González J, Ruiz I, et al. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA Study. AIDS. (2002) 16:605–13. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00012

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Ortega Suárez FJ, Sánchez Plumed J, Pérez Valentín MA, Pereira Palomo P, Muñoz Cepeda MA, Lorenzo Aguiar D, et al. Validation on the simplified medication adherence questionnaire (SMAQ) in renal transplant patients on tacrolimus. Nefrologia. (2011) 31:690–6. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.Aug.10973

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Del Rosario García B, Viña Romero MM, González Rosa V, Alarcón Payer C, Oliva Oliva L, Merino Alonso FJ, et al. Risk factors determining adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukaemia. J Oncol Pharm Pract. (2024) 30:902–6. doi: 10.1177/10781552231196130

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Briongos Figuero L, Bachiller Luque P, Palacios Martín T, González Sagrado M, Eiros Bouza J. Assessment of factors influencing health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients: Assessment of factors influencing health-related quality of life. HIV Med. (2011) 12:22–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00844.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Barraco A, Rossi A, Nicolò G, for the EPHAR Study Group. Description of study population and analysis of factors influencing adherence in the observational italian study “Evaluation of pharmacotherapy adherence in bipolar disorder” (EPHAR). CNS Neurosci Ther. (2012) 18:110–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00225.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Podzamczer D, Rozas N, Domingo P, Ocampo A, Van den Eynde E, Deig E, et al. ACTG-HIV symptoms changes in patients switched to RPV/FTC/TDF due to previous intolerance to CART. Interim analysis of the PRO-STR study. J Int AIDS Soc. (2014) 17:19814. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19814

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Intas G, Psara A, Stergiannis P, Chalari E, Sakkou A, Anagnostopoulos F. Compliance of patients with acute coronary syndrome with treatment following their hospitalization from the cardiac coronary unit. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2020) 1196:117–25. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-32637-1_12

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Castro GS, Aguilar-Alvarado CM, Zúñiga-Ramírez C, Sáenz-Farret M, Otero-Cerdeira E, Serrano-Dueñas M, et al. Adherence to treatment in Parkinson’s disease: A multicenter exploratory study with patients from six Latin American countries. Parkinsonism Related Disord. (2021) 93:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.10.028

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Abheiden CNH, van Reuler AVR, Fuijkschot WW, de Vries JIP, Thijs A, de Boer MA. Aspirin adherence during high-risk pregnancies, a questionnaire study. Pregnancy Hypertens. (2016) 6:350–5. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.08.232

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Chen LN, Suy S, Uhm S, Oermann EK, Ju AW, Chen V, et al. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Georgetown University experience. Radiat Oncol. (2013) 8:58. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-58

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Lei S, Piel N, Oermann EK, Chen V, Ju AW, Dahal KN, et al. Six-dimensional correction of intra-fractional prostate motion with cyberKnife stereotactic body radiation therapy. Front Oncol. (2011) 1:48. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2011.00048/abstract

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Lo Greco MC, Marletta G, Marano G, Fazio A, Buffettino E, Iudica A, et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy in localized, low–intermediate-risk prostate cancer: current and future prospectives. Medicina. (2023) 59:1144. doi: 10.3390/medicina59061144

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Jackson WC, Silva J, Hartman HE, Dess RT, Kishan AU, Beeler WH, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 6,000 patients treated on prospective studies. Int J Radiat OncologyBiologyPhysics. (2019) 104:778–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.03.051

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Gallagher L, Xiao J, Hsueh J, Shah S, Danner M, Zwart A, et al. Early biochemical outcomes following neoadjuvant/adjuvant relugolix with stereotactic body radiation therapy for intermediate to high risk prostate cancer. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1289249.

留言 (0)