Rectal prolapse is a benign but debilitating condition that significantly affects quality of life. It commonly affects those in their seventh decade of life and disproportionately affects women (1–7). It is defined as a circumferential, full-thickness protrusion of the rectal wall through the anal verge, often resulting in symptoms of incontinence, constipation, rectal bleeding, and psychological distress (1). Surgical intervention remains the definitive treatment for this condition, with the goals of preventing recurrence and improving continence (1–5, 8). Surgical management can be via transabdominal or perineal approaches, with many different techniques available, or definitively with an end colostomy. Although associated with higher recurrence, perineal approaches are generally preferred in elderly and high-risk patients (2, 9, 10).

Perineal proctosigmoidectomy, also known as the “Altemeier procedure”, is a perineal full-thickness resection of the prolapsed segment with a coloanal anastomosis (5, 9). This procedure avoids the physiological strain associated with a transabdominal approach and is often the preferred approach in elderly patients. Although our institution has reported considerably lower rates of recurrence in the past, historical data suggests that recurrence can be up to 58% and patients may also experience persistent incontinence with a perineal proctosigmoidectomy (1, 11). An alternative approach, often reserved for patients too frail to undergo bowel resection, is an anal encirclement procedure, also known as a “Thiersch procedure”. The procedure, first described in 1891, involved placing a silver wire around the anus (12). It is now more commonly performed with other materials such as a Nylon suture placed as a purse-string around the external sphincter to mechanically restrict the anus, preventing further prolapse and fecal incontinence (13–15). While anal encirclement is minimally invasive and can potentially be performed under local anesthetic alone, its recurrence rates are also up to 100% when performed without a proctosigmoidectomy (13).

Given the limitations of each procedure and the concerns with recurrence rates, surgeons at our institution started combining the two procedures 3 years ago in the hopes of improving outcomes. The rationale behind this combined approach is to reduce recurrence rates while maintaining the minimally invasive nature of a perineal approach. To our knowledge, there is only one prior study that has reported outcomes using a combination approach (16). Eftaiha et al. describe the use of a Bio-Thiersch mesh as an adjunct to perineal proctosigmoidectomy (16). Anal encirclement, however, is most commonly performed with a suture rather than a biological mesh implant (17). Here, we report the first study to evaluate the efficacy of routine anal encirclement with Nylon sutures in perineal proctosigmoidectomies. We hypothesize that combining these approaches will reduce recurrence rates compared to perineal proctosigmoidectomy alone.

MethodsThis was a retrospective analysis conducted at a tertiary care academic center (Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada) between July 2017 and October 2022. Informed consent was not required as the data was retrieved from our local database. The study was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Board (BIO-3318). Patients over 18 years of age with full-thickness rectal prolapse who underwent an operation with either a perineal proctosigmoidectomy or proctosigmoidectomy with anal encirclement were included. Rectal prolapse was defined as a circumferential, full-thickness protrusion of the rectal wall through the anal verge. Recommendation for proctosigmoidectomy was made at the surgeon's judgment, taking into account comorbidities, surgical history, and performance status. There was no standardized protocol, and the decision was made between surgeon and patient after informed discussion.

Variables were analyzed using Pearson's Chi-squared Test or Mann-Whitney U-Test as appropriate. Repeated measurement ANOVA was used to compare changes. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All data was analyzed using SPSS v.28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Recurrence of rectal prolapse was the primary outcome measured. Secondary outcomes were operative time, length of hospital stay, and complications.

Recurrence was identified based on a confirmed physical examination by a colorectal surgeon. At the time of the study, all prolapse surgery in the province was being performed by three colorectal surgeons at a single institution. Recurrence was identified either at scheduled follow-up or by re-referral. Absence of re-referral was considered a surrogate marker for lack of recurrence, as patients were not routinely re-examined to exclude recurrence. Because all prolapse surgery in our province was conducted at the study site, we are confident that cases of recurrence were not missed due to referral to other surgeons. We used the STROBE cohort checklist when writing our report (18).

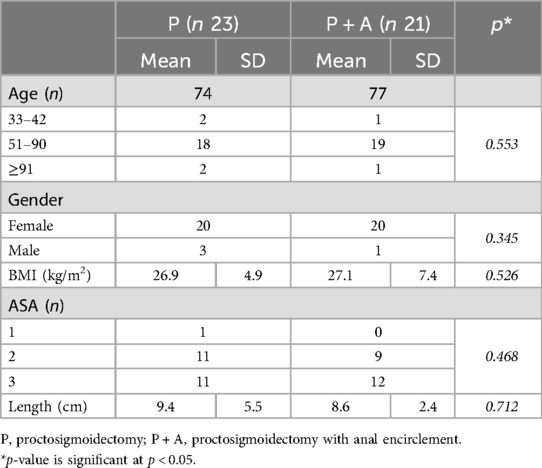

ResultsTwenty-three patients underwent a perineal proctosigmoidectomy (three of whom had a previous prolapse procedures, one Delorme, one Altemeier, and one abdominal rectopexy), and twenty-one patients underwent proctosigmoidectomy with encirclement (eight of whom had a prior perineal prolapse procedures, two Delorme and six Altemeiers). The two groups had similar baseline demographics, including age, BMI, gender, ASA score, and length of prolapse (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline demographics for comparing proctosigmoidectomy (P) vs. proctosigmoidectomy with anal encirclement (P + A).

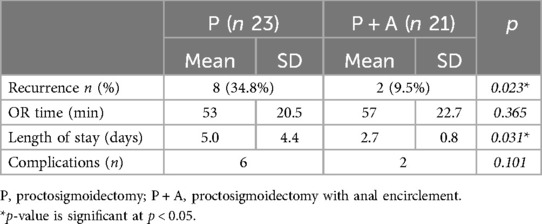

As seen in Table 2, patients who received the combined procedure had a significantly lower rate of recurrence (9.5%) compared to the proctosigmoidectomy group alone (34.8%) (p = 0.02). The outcomes were superior despite more re-do cases in the combined group.

Table 2. Comparison of outcomes between proctosigmoidectomy (P) vs. proctosigmoidectomy with anal encirclement (P + A).

The average length of stay for patients who underwent the combined procedure was 2.3 days less (5.0 vs. 2.7, p = 0.03). There was no difference in the operating time between the two groups (53 vs. 57 min, p = 0.36). There were five complications in the proctosigmoidectomy group compared to two in the combined group, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.10).

DiscussionOur results demonstrate that the addition of anal encirclement to proctosigmoidectomy reduces recurrence by 25% and shortens hospital stay by 2.3 days without increasing operative time or complication rates. The high recurrence rates historically associated with anal encirclement alone or perineal proctosigmoidectomy alone have limited their use, but this combined approach can substantially improve outcomes.

Our results are validated by previous studies. The recurrence rates in the control group are similar to what our group has previously reported (5). Although these rates are considerably lower than the literature, they are consistent with our local rates, emphasizing the value of adding anal encirclements to perineal repairs (1, 2). In a previous study by Eftaiha et al., 62 patients with perineal proctosigmoidectomy were compared to 25 patients who received a proctosigmoidectomy with an adjunct Biomesh Thiersch (16). Recurrence rates were 29% in the control group and 8% in the combined group (p = 0.048), which are similar to our results of 34.8% (control group) and 9.5% (combined group). Our data provides additional evidence that the combination procedure improves outcomes. In contrast to Eftaiha et al., we chose a Nylon suture for encirclement rather than biomesh placement, as it is readily available, cost-effective, and avoids further dissection (16).

We also found that the average length of stay for patients who underwent the combined procedure was 2.3 days less (p = 0.03). One of the criteria for discharge after proctosigmoidectomy at our institution is the return of bowel function, and we speculate that anal encirclement may improve continence by strengthening the external sphincter. A shorter hospital stay improves healthcare costs and is particularly helpful for elderly patients who benefit from minimized hospitalization (19). However, the increase length of stay could also be attributed to the management of anastomotic leaks in the proctosigmoidectomy alone group. The lack of difference in operative times and post-operative complications between the two groups further emphasizes that the addition of anal encirclement does not incur additional stress to the patients or the healthcare system.

There were six complications in the proctosigmoidectomy group compared to two in the combined group which did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). Three of the six complications in the proctosigmoidectomy group were anastomotic leaks. One leak was managed conservatively with IV antibiotics. The other two required take back to the operating room for a washout and formation of end colostomy. No patients were treated by proximal diversion while leaving the anastomosis in situ. In the combined group there was one leak, which was attributed to perforation at the posterior anastomotic site of a prior proctosigmoidectomy. We can only hypothesize as to the reason for increased leak rate in the proctosigmoidectomy alone group; the numbers are small, and it is difficult to draw definite conclusions. 2 of the 3 leaks were operated upon by the same surgeon, which raises the possibility of different surgical technique. However, it is important to consider that all patients were over the age of 85 and the increased frequency of leaks could be due to age-related factors, including diminished physiological reserves and impaired healing capacity inherent in this population. Future prospective studies could include the use of butylcholinesterase enzymes as a predictive factor for leak rates (21). Other complications in both groups included pelvic hematomas and urinary retention. Only one patient in the control group described incontinence at follow-up, and none in the combination group. Incontinence was assessed clinically pre and postoperatively. We did not identify any complications related to the encirclement itself in the combination group. There were no cases of suture protrusion or erosion identified.

Although patients in our study were not randomized, both groups were similar in baseline characteristics (average age, sex, BMI, ASA, and length of prolapse). These characteristics are also reflective of the general population that presents with prolapse (6). An interesting finding in our study was that there were more patients with recurrences in the intervention group, which would bias the results against the combined approach as previous prolapse is a risk factor for recurrence (17, 20). In fact, our study found that of the twenty-one patients who underwent a combined procedure, eight had a previous prolapse procedure and only one recurred (1/8). In the proctosigmoidectomy group, three patients had previously undergone a procedure for rectal prolapse and all three recurred (3/3).

This study has several limitations. The retrospective design, combined with the non-randomized small sample size, can lead to potential selection bias and limit generalizability. Another limitation of this study was that the time to recurrence was not measured, which could have provided nuanced insights into the long-term successes of the combined procedure. In the Swedish Rectal Prolapse Trial, 20% of recurrences occurred later than three years after surgery (8). We started performing routine anal encirclements only 3 years ago, and only 40% of patients in the control group had their operation more than three years ago, hence the 3-year follow-up. Finally, patients in our study were not routinely re-examined at the 3-year follow-up to rule out recurrence. Given the vast geography of our catchment area and the logistical challenges involved in transporting frail patients, we chose not to request in-person assessments. Instead, we used a lack of re-referral to confirm operative success at the 3-year mark. Future research should focus on larger, multi-center, randomized controlled trials to validate these findings.

ConclusionIn our opinion, the addition of routine anal encirclement with a Nylon suture is easy to learn and straightforward to perform. The participating surgeons taught themselves how to perform it by reviewing the literature and procedural videos. This additional maneuver can significantly reduce recurrence rates without adding any additional operative time, complications, or healthcare costs in high-risk patients with rectal prolapse.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Board (BIO-3318). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Ethics Committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because this was a retrospective study using data from a database.

Author contributionsAA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZB: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HR: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DG: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NG: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jason Park (Colorectal Surgeon – Vancouver General Hospital) for his advice and support for this project. The findings from this study were presented at the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract in Chicago, in 2023 (22).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Bordeianou L, Paquette I, Johnson E, Holubar SD, Gaertner W, Feingold DL, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. (2017) 60:1121–31. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000889

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Senapati A, Gray RG, Middleton LJ, Harding J, Hills RK, Armitage NCM, et al. PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. (2013) 15:858–68. doi: 10.1111/codi.12177

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Roy HM, Baig Z, Karimuddin AA, Raval MJ, Brown CJ, Phang PT, et al. A comparison of perineal stapled prolapse resection and the altemeier procedure at 2 Canadian academic hospitals. Can J Surg. (2023) 66:E8–12. doi: 10.1503/cjs.008421

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Gurland B, Zutshi M. “Rectal Prolapse”. The ASCRS Manual of Colon and Rectal Surgery. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2019). p. 777–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-01165-9_60

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Agradi S, Calabrò G, Bordoni L, Missaglia C, et al. Is it possible to reduce recurrences after altemeier’s procedure for complete rectal prolapse? Twenty-year experience in 130 consecutive patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. (2021) 406:1591–8. doi: 10.1007/s00423-021-02091-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Smedberg J, Graf W, Pekkari K, Hjern F. Comparison of four surgical approaches for rectal prolapse: multicentre randomized clinical trial. BJS Open. (2022) 6(1):zrab140. doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrab140

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Altomare DF, Binda G, Ganio E, De Nardi P, Giamundo P, Pescatori M. Long-term outcome of Altemeier’s procedure for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. (2009) 52:698–703. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ecffe

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Schabl L, Hull T, Ban K, Steele SR, Spivak A. Recurrence rates and risk factors in Altemeier procedure for rectal prolapse: a multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. (2024) 67(11):1465–74. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000003439

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Poole G V, Pennell TC, Myers RT, Hightower F. Modified Thiersch operation for rectal prolapse. Technique and results. Am Surg. (1985) 51:226–9.3157338

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

16. Eftaiha SM, Calata JF, Sugrue JJ, Marecik SJ, Prasad LM, Mellgren A, et al. Bio-Thiersch as an adjunct to perineal proctectomy reduces rates of recurrent rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. (2017) 60:187–93. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000723

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Warwick A, Zimmermann E, Boorman P, Smart N, Gee A. Recurrence rate after Delorme’s procedure with simultaneous placement of a Thiersch suture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. (2016) 98:419–21. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0148

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. (2007) 370:1453–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Thillainadesan J, Yumol MF, Suen M, Hilmer S, Naganathan V. Enhanced recovery after surgery in older adults undergoing colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. (2021) 64:1020–8. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002128

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Nugent E, Spivak A, Gurland BH, Shawki S, Hull TL, Zutshi M. Does the length of the prolapsed rectum impact outcome of surgical repair? Dis Colon Rectum. (2021) 64:601–8. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001856

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Verras GI, Mulita F. Butyrylcholinesterase levels correlate with surgical site infection risk and severity after colorectal surgery: a prospective single-center study. Front Surg. (2024) 11:1379410. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2024.1379410

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Amery A, Ginther N, Gill D. Addition of Anal Encirclement to Perineal Proctosigmoidectomy: A Retrospective Review. the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. Chicago: Gastroentrology (2023).

留言 (0)