Headache ranks as the fourth most common complaint in emergency departments (EDs), accounting for approximately 2 to 4% of all chief complaints (1–4). These headaches can be primary, such as migraine, tension-type headaches, and cluster headaches, or secondary to other conditions like hypertension, brain tumors, and hemorrhages (1).

Despite the lack of universally agreed-upon guidelines for headache management in EDs across countries (1, 5–7), pharmacological treatment remains a popular approach worldwide. Pharmacological treatments involve nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiemetic drugs, triptans, and corticosteroids (3). NSAIDs, which are the most prescribed medications for headaches, have been associated with adverse effects such as gastrointestinal complications, renal disturbances, and cardiovascular events (8, 9). Conversely, opioids are still actively prescribed for headaches in EDs, despite recommendations of avoidance due to analgesic tolerance, addiction, physical dependence, migraine chronification, increased recurrence rates, and lowered pain threshold (10–14).

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), including Chinese medicine, is widely used by individuals with headaches, either alone or in conjunction with conventional medications (15). Chinese medicine, which encompasses Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) decoctions, patented Chinese herbal medicine products (PCHMPs), acupuncture, and other modalities, is the mainstream CAM in China. Clinical trials have established the efficacy and safety of Chinese medicine in preventing primary headaches, including migraines and tension-type headaches (16, 17). Furthermore, the approach to managing migraines with Chinese medicine in outpatient settings has been documented (18). However, there is a lack of clarity regarding prescription patterns of Chinese medicine for acute headaches in real-world ED settings, as well as the characteristics of headache patients presenting to EDs. To address these gaps, we conducted this study to elucidate the characteristics of headaches in ED settings and the utilization of Chinese medicine for headache management in real-world clinical practice.

2 Methods 2.1 Study designThe study employs a retrospective analysis utilizing existing electronic medical records (EMRs) from ED at Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (GPHCM), which is the largest tertiary hospital that provides integrated Chinese medicine and conventional therapies for patients in China (19). The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of GPHCM with a waiver of consent (BE2024-188-01).

2.2 Data search and screeningThe EMRs with a first diagnosis of headache between 1 January 2023 and 31 December 2023 from four EDs at GPHCM were identified and retrieved by the Information Technology Department of GPHCM. The diagnosis of headache could either be general, without specifying the type or cause (as doctors may prioritize capturing the most prominent complaint, ‘headache,’ as a diagnosis), or it could be a specific type of headache such as migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. EMRs with incomplete information would be excluded for further screening.

2.3 Data extractionStructured data, such as triage category, age, gender, primary diagnoses and concurrent diagnoses, treatment methods, results of brain imaging including head computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), medicines and herbs were extracted by Zhenhui Mao and double checked by Shaohua Lyu. It should be noted that detailed headache variables like duration of headache, previous medication history for headache episodes, associated symptoms of headache and severity of headache were not consistently available in the EMRs. In addition, doses of herbs varied among patients according to individual conditions, therefore doses of herbs were not extracted or analyzed.

2.4 Data standardizationChinese medicinal herbs in different forms (granule or decoction piece) or being processed in various ways were standardized as one herb name as they share similar functions, in accordance to the World Flora Oline Plant List (20). For example, zhi gan cao (fried gan cao) was standardized as gan cao (Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma) since they were not distinguished in function. Conversely, the function of gan jiang (dried ginger, Zingiberis Rhizoma) is distinguished from that of sheng jiang (fresh ginger, Zingiberis Rhizoma Recens) according to the China Pharmacopoeia (version 2020) (21), therefore they were counted separately.

2.5 Data analysisIBS SPSS statistics (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was employed for descriptive analyses (22). Quantitative variables were described as mean with standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test when appropriate. While categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages and compared by Chi square test, where feasible.

Association rule construction based on the Apriori algorithm (23, 24) was conducted to identify high-frequency herb combinations, using SPSS Modeler software (version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

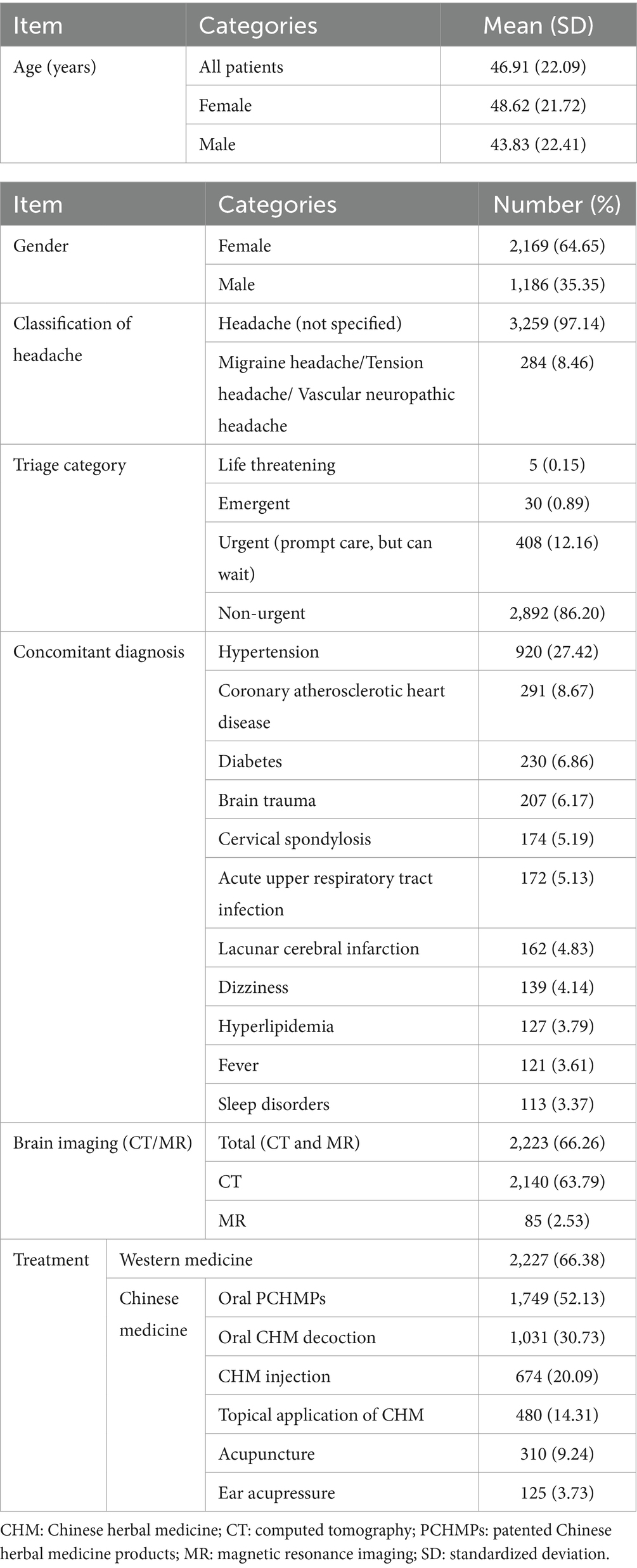

3 Results 3.1 General characteristicsA total of 3,355 patients attending EDs for headaches at GPHCM throughout the year 2023 were included in this study. Patients’ characteristics were presented in Table 1. Female patients constituted approximately 65% of the population and were older than male patients (48.62 years vs. 43.83 years, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients and treatment pattern.

Among the patients, only 8.46% of them were diagnosed with a primary headache, like migraine, tension-type and cluster headache. Up to 97.14% of the patients were roughly diagnosed with headaches without specific classification as their first diagnoses.

During the procedure of diagnoses, brain imaging (CT or MRI) was carried out among 66.26% of the patients, where head CT was run out for 63.79% of all headache patients and identified 0.98% of the ED patients as subarachnoid hemorrhage or intracranial hemorrhage.

In terms of concomitant diagnoses, hypertension ranked as the most common concurrent condition among 27.42% (n = 920) of the ED attendances, followed by coronary atherosclerotic heart disease among 8.67% of the headache patients.

A four-tier triage scale was utilized in EDs to sort or prioritize the ED attendances (25, 26). Only 1.04% of the patients were categorized into life-threatening or emergent emergencies, while up to 86.20% of the patients were justified as nonurgent conditions.

3.2 TreatmentIn ED settings, western medicine stood as the most popular treatment method among 2,227 (66.38%) patients, followed by PCHMPs (n = 1,749, 52.13%), and oral CHM decoction (n = 1,031, 30.73%). Other treatments included Chinese herbal injection, topical application of CHM, acupuncture, and ear acupressure (Table 1).

In addition, 1,670 patients were prescribed WM in combination with CHM decoctions or PCHMPs, 557 patients utilized WM alone, while 1,128 received Chinese medicine therapies without any WM.

3.2.1 Western medicineFlunarizine was the most frequently used western medicine by 314 (9.36%) patients, followed by diclofenac sodium sustained-release tablets (n = 261, 7.78%) and paracetamol and tramadol hydrochloride tablets (n = 220, 6.56%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Western medicine for headaches.

3.2.2 Patented Chinese herbal medicine productsThe oral PCHMPs list indicated that Tian shu tablet is the most frequently prescribed PCHMP to 1,237 (36.87%) patients, followed by Gastrodin injection among 566 (16.87%) patients, and Tong tian oral solution by 212 (6.32%) patients (Table 3).

Table 3. Patented Chinese herbal medicine products for headaches.

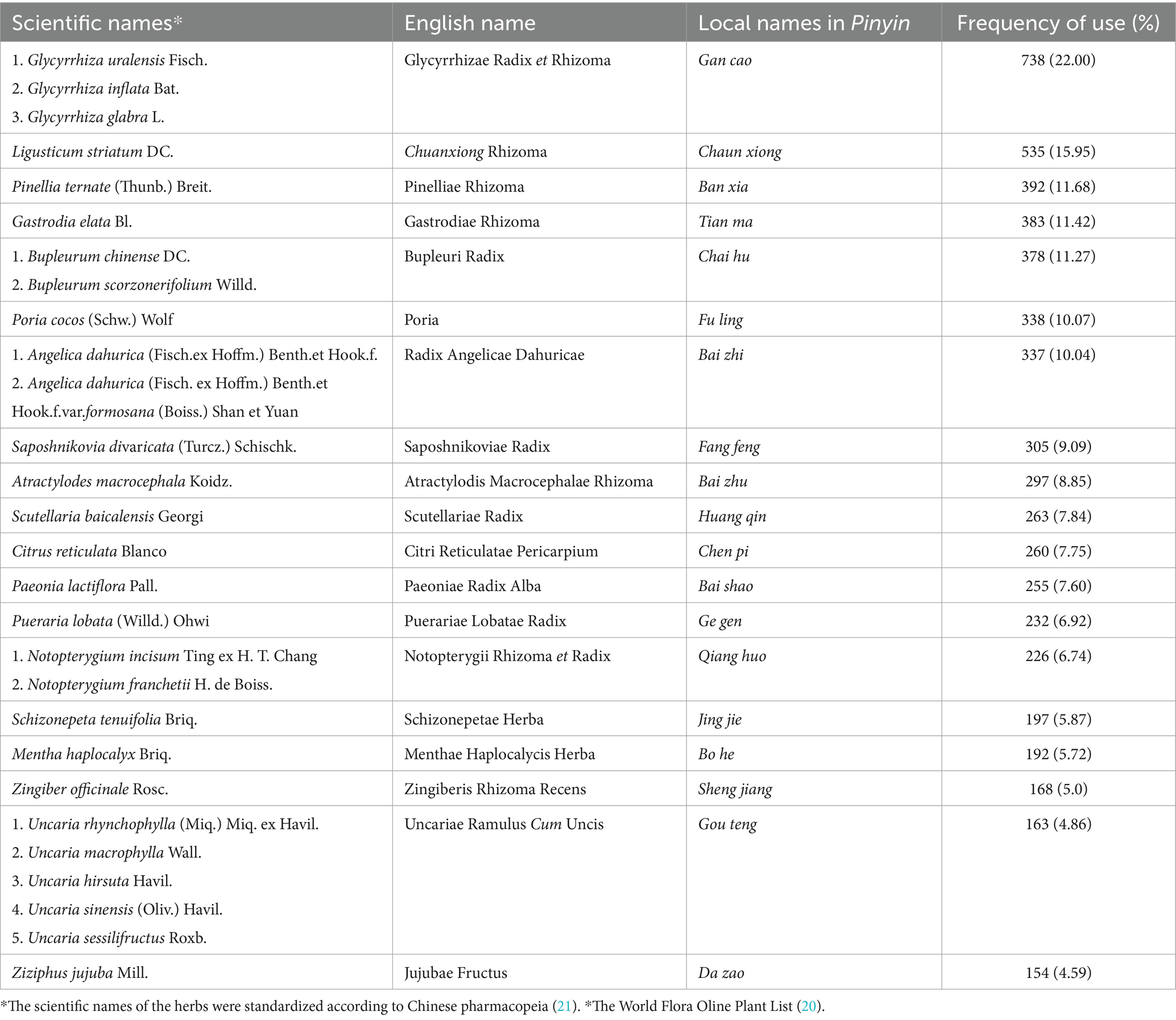

3.2.3 Oral Chinese herbal medicine decoctionAs indicated by Table 4, the most frequently used herbs as oral decoction for headaches in EDs include Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (gan cao, n = 738), Chuanxiong Rhizoma (chuan xiong, n = 535), Pinelliae Rhizoma (ban xia, n = 392), Gastrodiae Rhizoma (tian ma, n = 383), Bupleuri Radix (chai hu, n = 378), Poria (fu ling, n = 338), Radix Angelicae Dahuricae (bai zhi, n = 337) and Saposhnikoviae Radix (fang feng, n = 305).

Table 4. Herbs in oral decoctions for headaches.

Apriori algorithm-based association rules were conducted to identify the core herb combinations. The top ten herb combinations were displayed in Table 5, as indicated, the combinations mainly involved Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (gan cao), Notopterygii Rhizoma et Radix (qiang huo), Saposhnikoviae Radix (fang feng), Chuanxiong Rhizoma (chuan Xiong), Platycodon grandiflorum (Jacq) A.DC. (jie geng), Radix Angelicae Dahuricae (bai zhi), Schizonepetae Herba (jing jie), Asarum sieboldii Miq. (xi xin), Gastrodiae Rhizoma (tian ma) and Uncariae Ramulus Cum Uncis (gou teng), which are also the main ingredients of a classical formular Chuan xiong cha tiao san (CXCTS).

Table 5. Top ten core herb combinations for headaches from oral CHM decoctions.

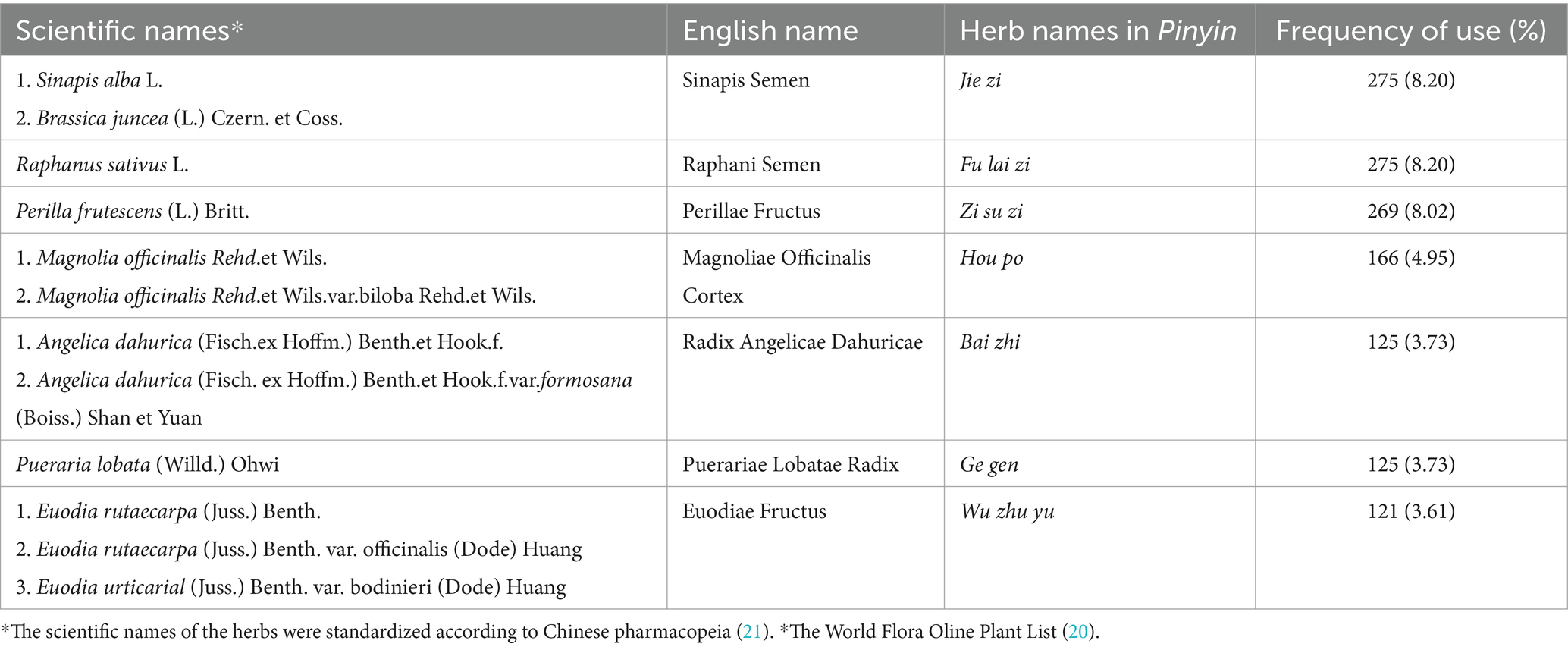

3.2.4 Topical application of Chinese herbal medicineThe top frequently used herbs as topical patch included Sinapis Semen (jie zi, n = 275), Raphani Semen (lai fu zi, n = 275) and Perillae Fructus (zi su zi, n = 269). These herbs were used in combinations. They functioned in warming meridians and expelling Wind in Chinese medicine theory (Table 6).

Table 6. Herbs in topical applications for headache.

4 Discussion 4.1 Summary of resultsThe study described characteristics of 3,355 ED attendances with headaches from four branches of a tertiary Chinese medicine hospital and summarized the regularity of Chinese medicine for headaches. The results of our study provide real-world clinicians’ experience of prescribing Chinese medicine for acute headaches, which can contribute to evidence-based medical decision-making for headaches in clinical practice and health policy making, along with other components such as clinical research evidence and patients’ preferences and values (27).

According to the results, females took a larger percentage over males, and these female patients aged elder than male patients. A previous study a reported a similar finding (28). This female predominance may be due to the fact that females are more susceptible to headaches, particularly migraines, which can be attributed to hormonal fluctuations (29, 30).

Similar to previous reports, the study again found that most headaches are benign (8, 31), as 86.20% of the patients were classified as less urgent or nonurgent according to the triage category (25, 26). However, headaches can also be secondary to serious and life-threatening conditions like hemorrhages and brain tumors. It is critical to recognize, evaluate, and appropriately manage these dangerous secondary headaches in prevention of potential long-term disability or death (31). Brain images were excessively scanned among headache patients (32–34). However, brain imaging was not recommended as a routine practice for uncomplicated headaches in USA (35). Indications for neuroimaging should be strongly based on the patient’s clinical history and a detailed physical examination (2, 36). It is critical to recognize the red flags of a secondary headache: systemic signs, neurological symptoms, sudden onset, older age at onset, progression, papilledema, positional or precipitated by Valsalva and pregnancy, in order to save unnecessary examinations and detect early signs of life-threatening conditions (37–40).

In addition, most of the diagnoses included in this study were categorized as general headaches without further precise classifications. Non-specific diagnoses were prevalent in EDs (41). However, it is hypothesized that the lack of specificity in these diagnoses may not meet the requirements of precision medicine.

The study involved a diverse range of western medications. Overall, western medicine was prescribed to two-thirds of the ED patients. However, in terms of acute medications, only one-tenth of the ED patients received NSAIDs or tramadol, which is relatively limited compared to the higher use of acute medications in other countries (32, 34). Conversely, headache-specific PCHMPs based on Chinese Pharmacopeia (21), such as Tian shu tablets, Gastrodin injection, and Tong tian oral solution, etc., were prescribed to over one-third of the headache patients. Studies have demonstrated their anti-headache, particular anti-migraine effects, from bench to bedside (42–47). Moreover, they have been recommended in clinical guideline for headaches (48).

Additionally, tailored CHM decoctions were prescribed for acute headaches in EDs, with core herb combinations being ingredients of CXCTS. CXCTS has been widely used for headaches since ancient times and is included in headache clinical guidelines (18, 48, 49). Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have shown that CXCTS can significantly improve headache frequency and duration, alone or in combination with western medicine (50, 51), through regulating neurotransmitter transmission, inflammation, angiogenesis, vasomotor, immunity and other pathways (52).

In addition to oral CHM treatment, topical applications of CHM have been introduced since ancient times, yet they are seldom utilized in contemporary outpatient departments (18, 53). It is noteworthy that CHM was applied topically to headache patients in EDs. However, unlike the intranasal method described in classical literature, the application of CHM patches on acupuncture points or focal areas of the headache is more prevalent in modern clinical practice (53). Additionally, the herbs commonly used in patches, such as jie zi, lai fu zi and zi su zi, differ significantly from those used intranasally in classical texts (53). Both laboratory and clinical evidence are necessary to support the use of topical CHM for headaches.

Based on the comparative use of acute medications and Chinese medicine in this study, we hypothesize that various forms of CHM therapies might serve as complementary and alternative methods to acute medications, potentially reducing acute medication usage and the risk of medication overuse (54). However, the hypothesis needs further verification in future clinical efficacy trials.

4.2 LimitationsSome inevitable limitations were identified in this study. Firstly, being a retrospective study, the study did not include quantitative assessment of the treatment effects of CHM for acute headaches in EDs. Secondly, subgroup treatment analyses based on diagnoses were not feasible as most of the diagnoses were not specifically verified. Thirdly, the study was conducted solely in four branches of a Chinese medicine hospital located in southern China, limiting the generalizability of the results due to potential geographic differences.

5 ConclusionThe majority of headache cases were non-urgent, and they were generally diagnosed without further classification. Although a significant portion of patients were prescribed Western medicine, acute medications were restricted in the EDs of this Chinese medicine hospital. Instead, a considerable percentage of headache patients opted for various forms of Chinese medicine, such as headache-specific PCHMPs, oral or topical applications of CHM, as alternatives to acute medications.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributionsZM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YF: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. JS: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision. SL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QS: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A6013), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2019YFC1708601), the Specific Fund of State Key Laboratory of Dampness Syndrome of Chinese Medicine (SZ2021ZZ14), State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China ([2022] no.1), Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province ([2023] no. 205), Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine for SL (YN2023MS13).

AcknowledgmentsThe authors extend gratitude to the patients for their unidentified data included in this study. Additionally, we acknowledged the contribution of the Technology Department from GPHCM for their input in exporting data.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbbreviationsCAM, Complementary and alternative medicine; CHM, Chinese herbal medicine; CT, computed tomography; CXCTS, Chuan xiong cha tiao san; ED, emergency department; GPHCM, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCHMPs, patented Chinese herbal medicine products; EMRs, electronic medical records.

References1. Peretz, A, Dujari, S, Cowan, R, and Minen, M. ACEP guidelines on acute nontraumatic headache diagnosis and Management in the Emergency Department, commentary on behalf of the refractory, inpatient, emergency care section of the American headache society. Headache. (2020) 60:643–6. doi: 10.1111/head.13744

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Giamberardino, MA, Affaitati, G, Costantini, R, Guglielmetti, M, and Martelletti, P. Acute headache management in emergency department. A narrative review. Intern Emerg Med. (2020) 15:109–17. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02266-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Zodda, D, Procopio, G, Gupta, A, Gupta, N, and Nusbaum, J. Points & pearls: evaluation and management of life-threatening headaches in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. (2019) 21:1–2.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

5. Critical Care Group of Emergency Medicine Branch of Chinese Medical Association Expert Consensus Group on Management of Adult Analgesia Sedation and Delirium in Emergency. Expert consensus on emergency Management of Analgesia, sedation, and delirium in adults. Chinese J Emerg Med. (2023) 32:1594–609. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2023.12.004

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Ng, JY, and Hanna, C. Headache and migraine clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review and assessment of complementary and alternative medicine recommendations. BMC Compl Med Ther. (2021) 21:236. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03401-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Ducros, A, de Gaalon, S, Roos, C, Donnet, A, Giraud, P, Guégan-Massardier, E, et al. Revised guidelines of the French headache society for the diagnosis and management of migraine in adults. Part 2: pharmacological treatment. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2021) 177:734–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.07.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Doretti, A, Shestaritc, I, Ungaro, D, Lee, JI, Lymperopoulos, L, Kokoti, L, et al. Headaches in the emergency department -a survey of patients' characteristics, facts and needs. J Headache Pain. (2019) 20:100. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1053-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Harirforoosh, S, Asghar, W, and Jamali, F. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal complications. J Pharm Pharm Sci. (2013) 16:821–47. doi: 10.18433/J3VW2F

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Minen, MT, Lindberg, K, Wells, RE, Suzuki, J, Grudzen, C, Balcer, L, et al. Survey of opioid and barbiturate prescriptions in patients attending a tertiary care headache center. Headache. (2015) 55:1183–91. doi: 10.1111/head.12645

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Paul, AK, Smith, CM, Rahmatullah, M, Nissapatorn, V, Wilairatana, P, Spetea, M, et al. Opioid analgesia and opioid-induced adverse effects: A Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). (2021) 14. doi: 10.3390/ph14111091

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Tornabene, SV, Deutsch, R, Davis, DP, Chan, TC, and Vilke, GM. Evaluating the use and timing of opioids for the treatment of migraine headaches in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. (2009) 36:333–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.07.068

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Adams, J, Barbery, G, and Lui, C-W. Complementary and alternative medicine use for headache and migraine: a critical review of the literature. Headache. (2013) 53:459–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02271.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Shi, YH, Wang, Y, Fu, H, Xu, Z, Zeng, H, and Zheng, GQ. Chinese herbal medicine for headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality randomized controlled trials. Phytomedicine. (2019) 57:315–30. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.039

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Lyu, S, Zhang, CS, Guo, X, Zhang, AL, Sun, J, Chen, G, et al. Efficacy and safety of Oral Chinese herbal medicine for migraine: a systematic review and Meta-analyses using robust variance estimation model. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:889336. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.889336

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Lyu, S, Zhang, CS, Sun, J, Weng, H, Xue, CC, Guo, X, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for migraine management: a hospital-based retrospective analysis of electronic medical records. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9:936234. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.936234

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Corp, I. IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp. (2017).

23. Agrawal, R, Imieliński, T, and Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data; Washington, D.C., USA: Association for Computing Machinery; (1993). p. 207–216.

25. Peng, L, and Hammad, K. Current status of emergency department triage in mainland China: a narrative review of the literature. Nurs Health Sci. (2015) 17:148–58. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12159

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Expert Group on Emergency Pre-examination and TriageShi, D, Liu, X, and Zhou, Y. Consensus of experts on emergency pre-examination and triage. Chin J Emerg Med. (2018) 27:599–604. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2018.06.006

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Dawes, M, Summerskill, W, Glasziou, P, Cartabellotta, A, Martin, J, Hopayian, K, et al. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. BMC Med Educ. (2005) 5:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Patient Experiences in Australia: Summary of Findings, 2016–17 Quality Declaration. Australia: Statistics ABo (2017).

30. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Neurol. (2024) 23:344–81. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00038-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Yang, S, Orlova, Y, Lipe, A, Boren, M, Hincapie-Castillo, JM, Park, H, et al. Trends in the Management of Headache Disorders in US emergency departments: analysis of 2007-2018 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Data. J Clin Med. (2022) 11. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051401

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Beck, S, Kinnear, FB, Maree Kelly, A, Chu, KH, Sen Kuan, W, Keijzers, G, et al. Clinical presentation and assessment of older patients presenting with headache to emergency departments: a multicentre observational study. Australas J Ageing. (2022) 41:126–37. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12999

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Kelly, AM, Kuan, WS, Chu, KH, Kinnear, FB, Keijzers, G, Karamercan, MA, et al. Epidemiology, investigation, management, and outcome of headache in emergency departments (HEAD study)-a multinational observational study. Headache. (2021) 61:1539–52. doi: 10.1111/head.14230

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Utukuri, PS, Shih, RY, Ajam, AA, Callahan, KE, Chen, D, Dunkle, JW, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® headache: 2022 update. J Am Coll Radiol. (2023) 20:S70–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2023.02.018

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Do, TP, Remmers, A, Schytz, HW, Schankin, C, Nelson, SE, Obermann, M, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology. (2019) 92:134–44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006697

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Wijeratne, T, Wijeratne, C, Korajkic, N, Bird, S, Sales, C, and Riederer, F. Secondary headaches—red and green flags and their significance for diagnostics. eNeurologicalSci. (2023) 32:100473. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2023.100473

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Raam, R, and Tabatabai, RR. Headache in the emergency department: avoiding misdiagnosis of dangerous secondary causes, an update. Emerg Med Clin North Am. (2021) 39:67–85. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2020.09.004

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Ukkonen, M, Jämsen, E, Zeitlin, R, and Pauniaho, S-L. Emergency department visits in older patients: a population-based survey. BMC Emerg Med. (2019) 19:20. doi: 10.1186/s12873-019-0236-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Xia, W, Zhu, M, Zhang, Z, Kong, D, Xiao, W, Jia, L, et al. Effect of Tianshu capsule in treatment of migraine: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Tradit Chin Med. (2013) 33:9–14. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(13)60093-X

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Yu, S, Ran, Y, Xiao, W, Tang, W, Zhao, J, Chen, W, et al. Treatment of migraines with Tianshu capsule: a multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2019) 19:370. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2775-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Guan, J, Zhang, X, Feng, B, Zhao, D, Zhao, T, Chang, S, et al. Simultaneous determination of ferulic acid and gastrodin of Tianshu capsule in rat plasma by ultra-fast liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry and its application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study in normal and migraine rats. J Sep Sci. (2017) 40:4120–7. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201700665

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Liu, L, Li, H, Wang, Z, Yao, X, Xiao, W, and Yu, Y. Exploring the anti-migraine effects of Tianshu capsule: chemical profile, metabolic behavior, and therapeutic mechanisms. Phytomedicine. (2024) 131:155766. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155766

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Xu, Z, Jia, M, Liang, X, Wei, J, Fu, G, Lei, L, et al. Clinical practice guideline for migraine with traditional Chinese medicine (draft version for comments). Chinese J Trad Chin Med. (2020) 45:5057–67. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20200903.502

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Zhang, D, and Wang, Y. Effect of Tongtian oral liquid for migraine with Chinese medicine syndrome of blood stasis and wind. Inner Mongolia J Trad Chin Med. (2024) 43:51–3. doi: 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2024.05.034

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Ren, Y, Li, H, Wang, Y, and Chen, Y. Report of guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of common internal diseases in Chinese medicine: headache. J Evid Based Med. (2020) 13:70–80. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12378

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Zhang, CS, Lyu, S, Zhang, AL, Guo, X, Sun, J, Lu, C, et al. Natural products for migraine: data-mining analyses of Chinese medicine classical literature. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:995559. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.995559

留言 (0)