Abdominal organs, such as the liver, pancreas, or kidneys, fluctuate significantly in the craniocaudal direction of the respiratory tract during breathing. The position or angle of the blood vessels differs between end-inspiration and end-expiration;[1,2] these movements induce a change in the aortomesenteric angle, that is, the branching angle between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The duration of human respiration is longer in the expiration phase than in the inspiration phase.[3] Presumably, the position of the vessels at end-expiration is closer to their usual distribution than that at end-inspiration. The aortomesenteric angle can be identified in computed tomography (CT); however, CT scans require breath-holding to reduce motion artifacts, and the inspiration phase is commonly believed to be better tolerated by patients.[4] Therefore, abdominal CT is often performed at end-inspiration. However, the position or angle of the vessels in CT images performed at end-inspiration is likely to be different from their usual position closer to end-expiration. In addition, a narrow aortomesenteric angle causes severe stenosis of the duodenum or left kidney vein, resulting in diseases such as SMA syndrome or nutcracker syndrome. These diseases cause abdominal pain and venous stasis, among other symptoms. To diagnose SMA syndrome or nutcracker syndrome, the aortomesenteric angle should be determined.[5] However, the aortomesenteric angle could be different in the normal state from that in CT images during inspiration.

Several studies have confirmed the branching angle of blood vessels at end-inspiration and end-expiration, but very few have reported the relationship between the angle of the vessels and physical factors, such as body mass index (BMI), visceral fat, or respiratory variability.[1,2,6-9]

Changes in the aortomesenteric angle, influenced by respiratory phases, are crucial in diagnosing conditions like SMA syndrome. This study aims to elucidate these changes and their relationship with anthropometric factors.

MATERIAL AND METHODSThis retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of our institution (REC2024-115). The need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Information regarding this study was available on the home page of our university.

Study participants and data acquisitionThis retrospective study included 59 patients who underwent contrast-enhanced CT. The study population comprised all adult patients who underwent contrast-enhanced CT at both end-inspiration and end-expiration at our hospital between 2015 and 2020 because both were clinically necessary. All patients had a history of hypertension and were scheduled for adrenal venous sampling.

The weight and height of the patients were extracted from the database, and their BMIs were calculated.

CT imagingAll CT examinations were performed using 64- or 320-row multidetector scanners (Aquillion 64 and Aquillion ONE GENESIS, Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). The scanning parameters were as follows: Tube voltage, 135 kVp; matrix, 512 × 512; field of view, 350 mm; gantry rotation time, 0.5 s; and slice thickness, 1 mm. Automatic exposure control with a fixed noise figure (standard deviation 10– 11 at 5-mm thickness) was used for the tube current. For contrast-enhanced CT, weight-based intravenous injection of contrast agent was used with low-osmolar iohexol, 350 mg of iodine/mL (Omnipaque 350, GE Healthcare), or 370 mg of iodine/mL (Iopamiron, GE Healthcare) with 600 mg of iodine/kg. The injection rate was set at 3–6 mL/s, and intravenous contrast material volume was set at 100–150 mL. CT scans were performed for 45 s at end-inspiration and 70 s at end-expiration after injection of the contrast material. Additional scans were performed at 90 s and 120 s post-injection, but this study utilized the data obtained at 45 s and 70 s. The rationale for scanning in both phases was two reasons: To obtain expiratory vascular imaging for possible interventional radiology procedures and to reduce patient burden by avoiding multiple inspiratory scans in a short period of time.

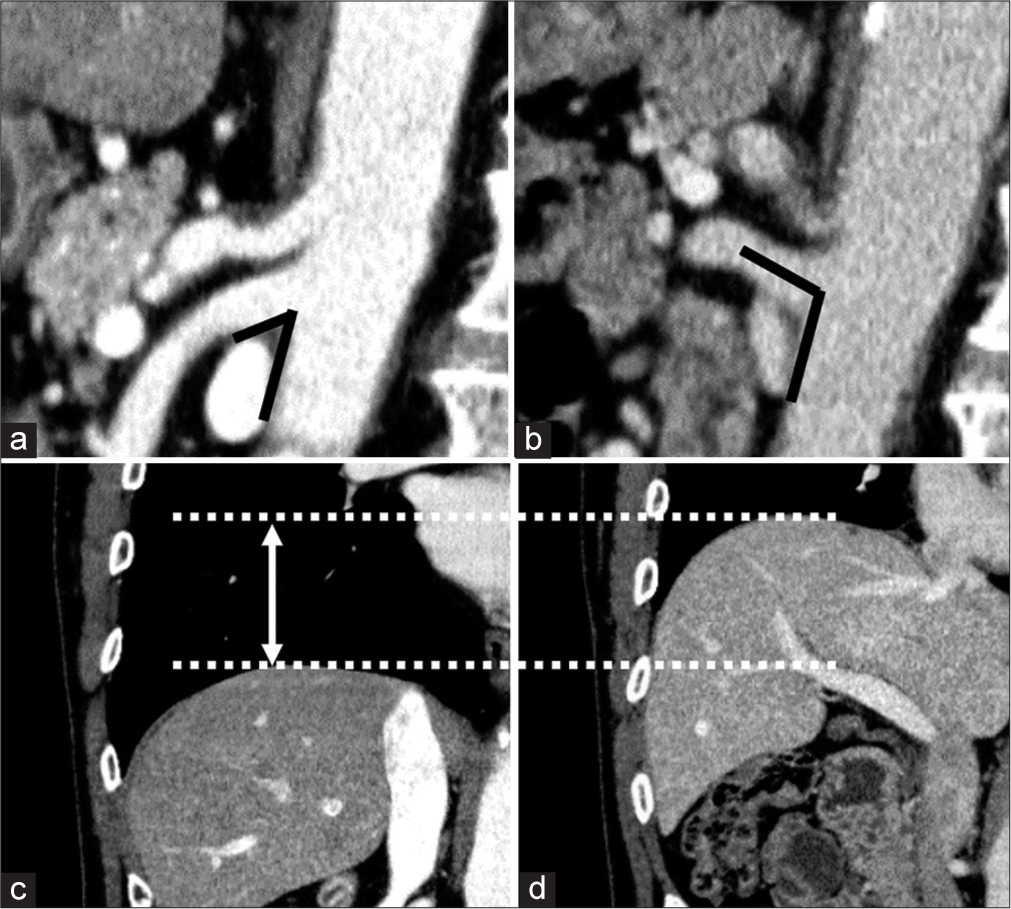

Image analysisThe aortomesenteric angle was measured using sagittal reconstructed images. In addition, visceral and subcutaneous fat at the height of the navel on axial CT images were measured semiautomatically using the workstation. These fat areas were defined as regions with Hounsfield units between −160 and −20 in the CT images. The workstation software EV Insite (PSP Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was employed for measurement and analysis. Sagittal CT images were reconstructed through the center of the SMA, while coronal CT images were reconstructed through the center of the abdominal aorta at the level of the celiac artery bifurcation. Two radiologists (with 12 and 22 years of experience, respectively) reviewed the reformatted CT images. The aortomesenteric angle was measured in the sagittal reconstructed images, and the maximum diaphragm motion was measured in coronal reconstructed images. Sufficient inspiration was confirmed by the diaphragm motion. Insufficient inspiration was indicated by a diaphragm motion of <20 mm, based on a previous report indicating that the average movement of the diaphragm is 27 mm.[10] Considering variations due to age and sex, a threshold of 20 mm was established.[10] The angle between the inferior edge of the SMA and the anterior edge of the aorta immediately inferior to the SMA origin was measured. Figure 1 illustrates an instance of the measured angles and the diaphragm motion. For disagreement regarding the degree of aortomesenteric angle between the two radiologists, the decision was reached by consensus. The variation rate in these angles at end-inspiration and end-expiration was calculated as follows:

Variation rate=Angleinspiration−AngleexpirationAngleinspiration×100

Export to PPT

Statistical analysisPearson’s or Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to assess correlations. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Normality was tested using the Shapiro−Wilk test. Comparisons of the angle at between end-inspiration and end-expiration were assessed using the paired t-test and Mann−Whitney U-test, as appropriate. We evaluated the correlation between these angles or the variation rate and height, weight, BMI, visceral fat, subcutaneous fat, and diaphragm motion. For the correlation analyses, the Pearson or Spearman methods were used as appropriate.

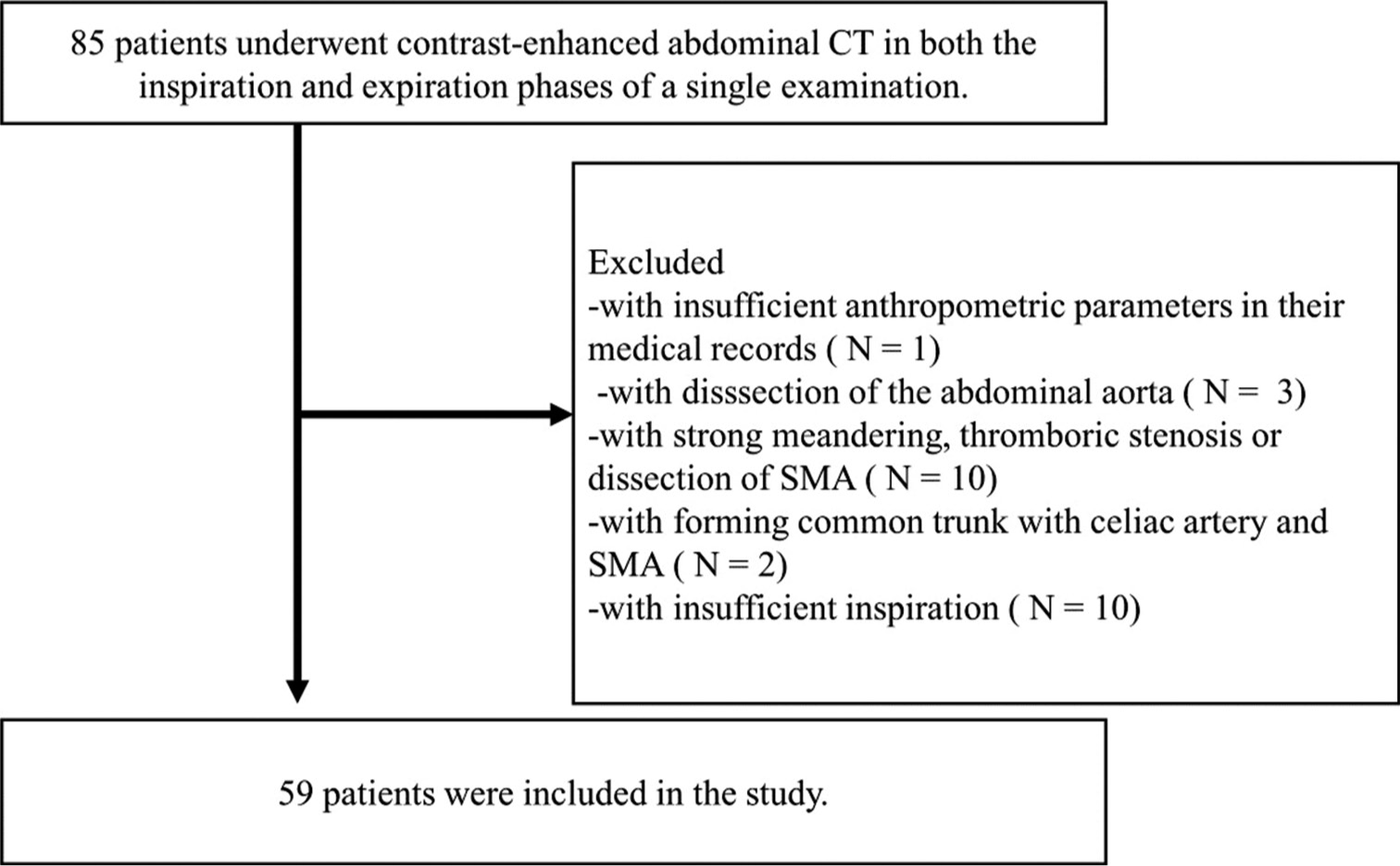

RESULTSA total of 85 patients underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal CT at both end-inspiration and end-expiration of a single examination. Of these, patients with dissection of the abdominal aorta, thrombotic stenosis or dissection of the SMA, formation of a common trunk by celiac artery and SMA, and insufficient inspiration were excluded from the study. Our final study population comprised 59 patients (33 males and 26 females; mean age, 51.20 ± 11.07 years). Figure 2 exhibits the chart for the inclusion and exclusion of participants. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All measured data showed normal distributions except for the variation rate. The correlations of the angle with age and anthropometric parameters were analyzed by Pearson’s correlation coefficients, while correlations between variability and parameters were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. When comparing males and females, no significant differences were identified in BMI, diaphragm motion, or subcutaneous fat. However, height, weight, and visceral fat was significantly greater in males.

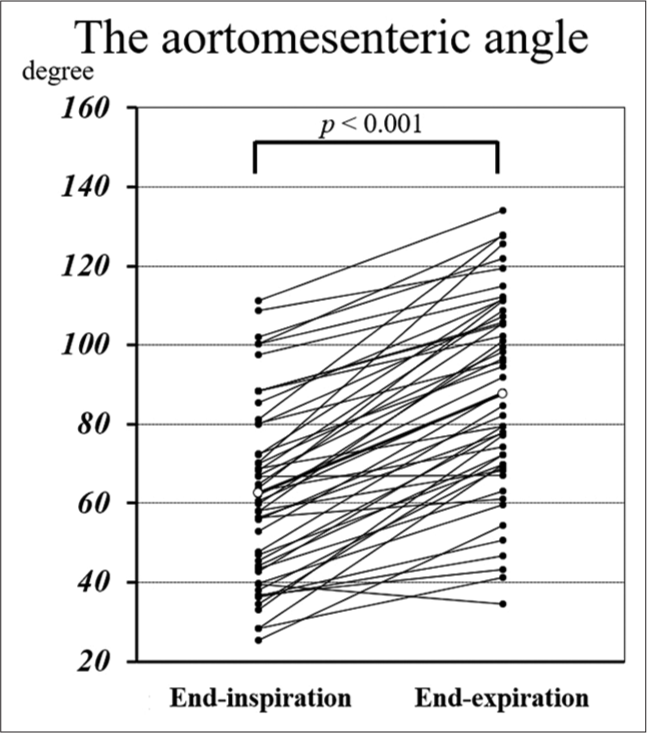

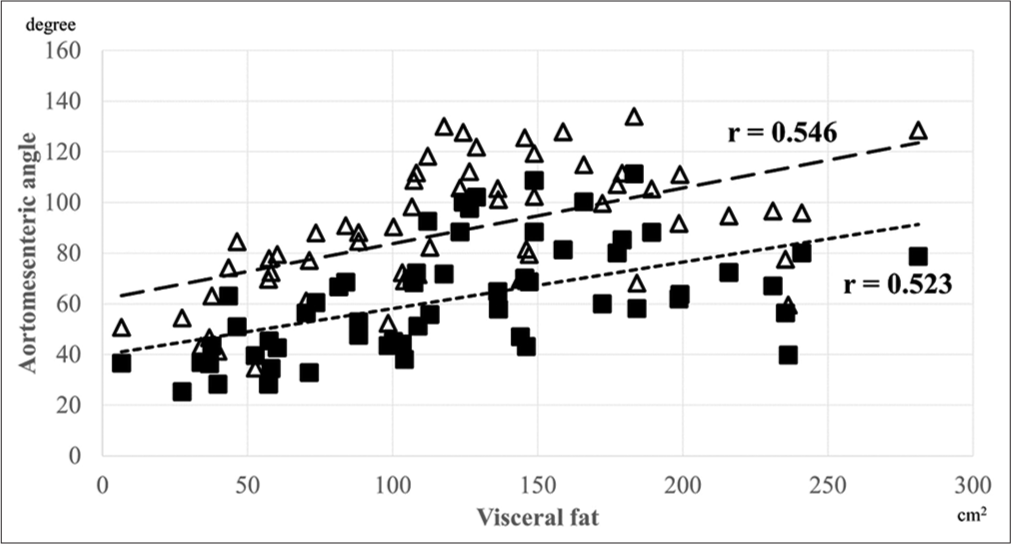

The aortomesenteric angle measurements at both end-inspiration and end-expiration were normally distributed, and the angle at end-expiration was significantly larger according to the paired t-test (62.22 ± 21.90°, 95% confidence interval [CI] 56.51–67.93 vs. 88.65 ± 25.15°, 95% CI 82.09–95.20, P < 0.001). Figure 3 demonstrates the distribution of the aortomesenteric angles during end-inspiration and end-expiration. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to evaluate the correlation between these vessel angles and height, weight, BMI, visceral fat, subcutaneous fat, and diaphragm motion [Table 2]. The aortomesenteric angles at both end-inspiration and end-expiration did not correlate significantly with height or diaphragm motion but did with other anthropometric parameters. Specifically, the correlation between visceral fat and angle was the highest for both end-inspiration (r = 0.523, P < 0.001) and end-expiration (r = 0.546, P < 0.001). Figure 4 shows the correlation between the aortomesenteric angles at end-inspiration or end-expiration and visceral fat. The variation rate of aortomesenteric angle was only correlated with diaphragm motion (r = 0.550, P < 0.001; [Table 3]).

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Table 1: Patient characteristics.

Male Female P-valuea Number 32 27 Age (years) 49.48±11.05 52.66±11.06 0.276 Height (cm) 167.95±6.17 157.42±6.04 <0.001* Weight (kg) 77.63±11.78 67.22±11.71 0.003* BMI (kg/m2) 27.63±3.80 26.49±4.06 0.271 Subcutaneous fat (cm2) 181.22±62.23 207.78±86.79 0.178 Visceral fat (cm2) 144.16±63.76 95.70±50.28 0.002* Diaphragm motion (mm) 48.56±13.85 47.74±14.82 0.826Table 2: The correlation between aortomesenteric angle and anthropometric parameters at both end-inspiration and end-expiration.

End-inspiration End-expiration Pearson’s coefficient P-value Pearson’s coefficient P-value Height 0.102 0.443 0.2 0.128 Weight 0.455 <0.001 0.538 <0.001 BMI 0.46 <0.001 0.502 <0.001 Subcutaneous fat 0.429 <0.001 0.441 <0.001 Visceral fat 0.523 <0.001 0.546 <0.001 Diaphragm motion −0.299 0.021 −0.018 0.893Table 3: Correlation between variation rate of aortomesenteric angle and anthropometric parameters.

Variation rate Spearman’s coefficient P-value Height 0.123 0.355 Weight 0.019 0.885 BMI −0.095 0.473 Subcutaneous fat −0.087 0.514 Visceral fat −0.159 0.23 Diaphragm motion 0.55 <0.001 Key findings includeThe aortomesenteric angle at end-expiration was significantly larger than at end-inspiration (P < 0.001).

The strongest correlation was with visceral fat (r = 0.546, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSIONWe evaluated the aortomesenteric angles at both end-inspiration and end-expiration and the correlation between these angles and anthropometric parameters, such as BMI, visceral fat, and diaphragm motion. First, while the aortomesenteric angle at both end-inspiration and end-expiration demonstrated a relationship with body weight and BMI, the most significant correlation were observed with visceral fat. This suggests that visceral fat has a greater impact on the aortomesenteric angle than general body weight or BMI. In addition, there was no correlation between the variation rate in the aortomesenteric angle and BMI or visceral fat. Instead, this variation rate is most closely associated with diaphragm motion. This indicates a difficulty in predicting the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle from anthropometric parameters such as BMI and visceral fat, and that respiratory variability, such as diaphragm motion, is a relevant factor in the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle.

The present study showed that the aortomesenteric angle is correlated with body weight and BMI at both end-inspiration and end-expiration, but the strongest link is with visceral fat. Several studies reported a positive correlation between BMI and the angle of emergence in celiac arteries.[11,12] In addition, one study reported a positive relationship between BMI and the aortomesenteric angle, suggesting the role of BMI in predicting SMA syndrome.[13] Another study reported the superiority of visceral fat volume over BMI in evaluating the aortomesenteric angle.[7] However, the novelty of the present study lies in the association between visceral fat and the aortomesenteric angle as observed to be strongest for both end-inspiration and end-expiration. This suggests that visceral fat, rather than just overall bodyweight or BMI, has a more critical role in the anatomical variations of the SMA. Furthermore, few studies have reported that females have less visceral fat than males,[14,15] which could possibly explain why SMA syndrome is more common in females, thereby resulting in more acute aortomesenteric angles. One of the diagnostic criteria for SMA syndrome is an aortomesenteric angle of 22° or less.[5] In addition, nutcracker syndrome, which causes hematuria, gonadal vein reflux, and pelvic varices, is caused by compression of the left renal vein by the SMA and aorta, and nutcracker syndrome occurs at an aortomesenteric angle of 35° or less.[5] In our study, only five patients had an aortomesenteric angle of 35° or less at end-inspiration and only one had an angle <35° at end-expiration. The dynamics of breathing are such that the duration of expiration is longer than that of inspiration, suggesting that the blood vessels are more frequently positioned in the way they would be during expiration. Moreover, the aortomesenteric angle is sharper during inspiration than during expiration. However, a possibility of overdiagnosis exists when the aortomesenteric angle is evaluated by CT during inspiration. Furthermore, visceral fat increases with age,[16,17] suggesting the possibility that the aortomesenteric angle may also increase with age. While it is considered that the cause of SMA syndrome or nutcracker syndrome is not solely due to the aortomesenteric angle, the prevalence of this condition in young women might be influenced by the amount of visceral fat they have.

Another important finding identified that the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle at between end-inspiration and end-expiration does not correlate with BMI or visceral fat. Furthermore, no correlation with other anthropometric parameters was observed. Instead, the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle is closely linked with diaphragm motion. This finding is supported by previous research demonstrating that the SMA undergoes positional changes during respiration, moving superiorly and posteriorly with expiration.[2] In addition, the angle of the SMA varies between inspiration and expiration.[1] Our study revealed that diaphragm motion is a significant factor influencing the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle during respiration, rather than body composition metrics such as BMI or visceral fat. This finding suggests a more dynamic interaction between respiratory mechanics and vascular anatomy than previously understood. The degree of change in the aortomesenteric angle is difficult to predict with intravital parameters, and changes due to diaphragmatic motion, that is, the patient’s effort to breathe, are considered important. Therefore, this finding emphasizes the importance of considering diaphragm motions in understanding the variation in the aortomesenteric angle during different respiratory phases.

The implications of our study are significant for clinical practice and future research. Compared to BMI, the strong correlation between visceral fat and the aortomesenteric angle suggests that assessments of visceral fat could be an important factor in predicting and managing conditions related to SMA anatomy, such as SMA syndrome or nutcracker syndrome. Furthermore, the discovery that diaphragm motion, rather than BMI or visceral fat, influences the variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle underscores the need for a more dynamic approach in interventional radiology. Several studies in radiation oncology have found better stability and reproducibility of abdominal organ positioning at end-expiration.[18-20] In addition, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is performed during interventional radiology and often at end-expiration because DSA in this phase is better at depicting vascular vessels and reduces image degradation caused by respiratory motion.[21-23] Abdominal CT at end-expiration is considered useful to confirm the location of organs or vessels for patients scheduled for abdominal surgery or interventional radiology.

Our study has a few limitations. First, the sample size of 59 patients limits the generalizability of our findings. A larger study would provide more robust data. Second, it did not consider the meandering of the artery. In this study, the angles of the celiac artery and SMA were assessed in a single slice of the sagittal CT image. If the meandering of the measured artery is strong, it is difficult to measure the angle, and these angles may not be evaluated accurately. Third, the study assessed the relationship between respiration and the angles of the artery; however, whether the patient was able to breathe adequately during inspiration and expiration was not considered. In this study, the distance of diaphragmatic movement was used to determine whether inspiration was sufficient. However, the degree of inspiration and expiration depends on the patient’s effort, and we did not determine whether the patient was able to breathe adequately. In addition, we did not evaluate the presence or absence of respiratory diseases in this study. Moreover, there were many older and hypertension patients in this study; other studies in healthy young adults may have provided different results. Another limitation is that the inspiration CT was done at 45 s after contrast injection while expiration CT was done at 70 s. This again has the potential to introduce bias.

Our findings highlight the significant role of visceral fat in influencing the aortomesenteric angle. This has clinical implications for diagnosing SMA syndrome. However, the study’s limitations include a small sample size and lack of consideration for respiratory diseases. Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths. It is one of the few studies to correlate the aortomesenteric angle with visceral fat and diaphragm motion, providing new insights into vascular anatomy. In addition, our use of contrast-enhanced CT imaging at both end-inspiration and end-expiration offers a high level of detail in our analysis. These strengths contribute significantly to the field, enhancing our understanding of SMA dynamics and their clinical implications.

CONCLUSIONThe aortomesenteric angle is significantly greater at end-expiration than at end-inspiration, correlating more strongly with visceral fat than with BMI or weight in both phases. The variation rate of the aortomesenteric angle is associated with diaphragm motion and may relate to effortful respiration. These findings have practical implications for the practice of abdominal laparotomy and interventional radiology, where understanding the dynamics of respiratory mechanics and vascular anatomy can aid in planning surgical interventions, potentially reducing complications or improving imaging techniques. Future studies should explore the impact of respiratory diseases on the aortomesenteric angle and investigate the potential for using visceral fat assessments in clinical diagnostics.

留言 (0)