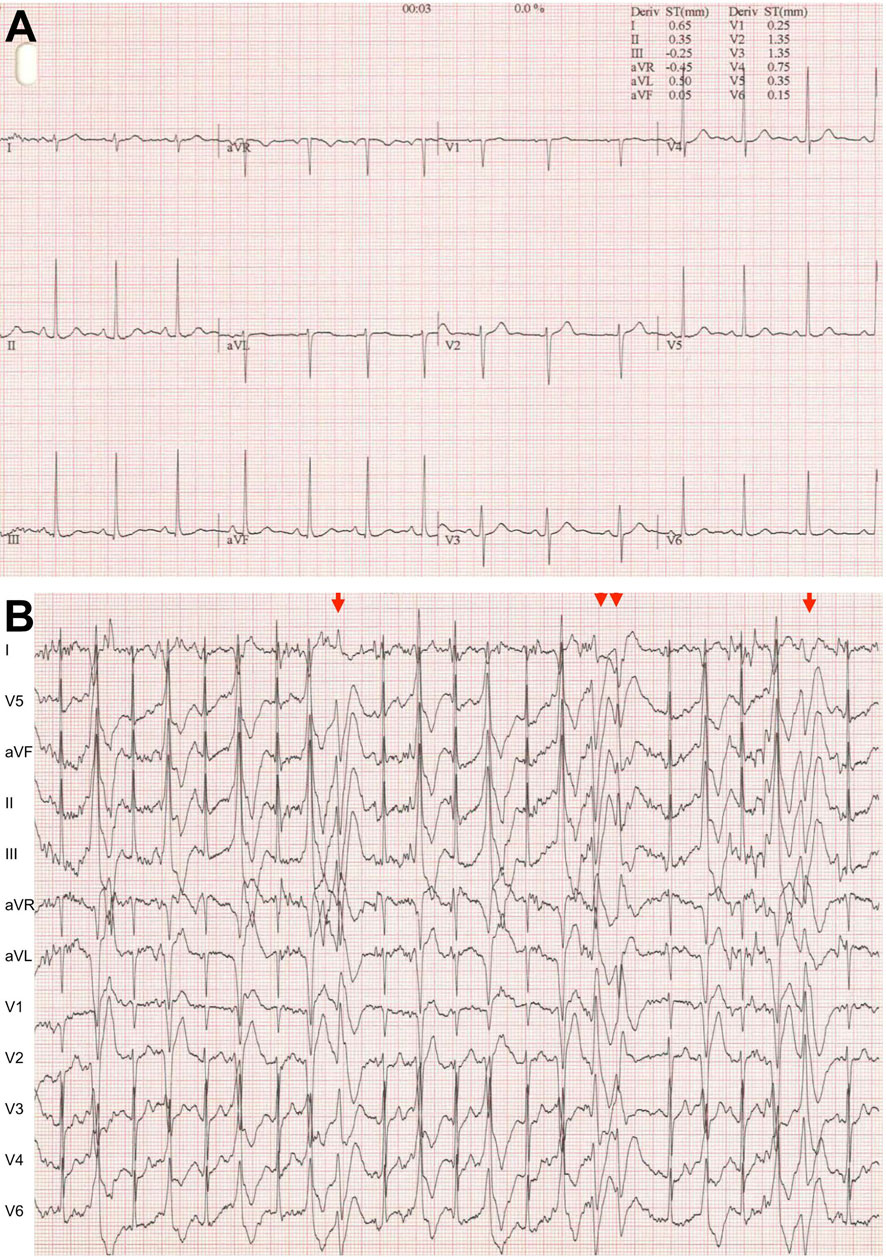

The ryanodine receptor (RyR2) plays a vital role in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by mediating sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Abnormal RyR2 function resulting in aberrant cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling leads to arrhythmias and sudden death. To date, around 350 missense mutations have been identified in RyR2, most linked with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (Venetucci et al., 2012; Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022). CPVT, a relatively common disease estimated to affect one in 10,000 people, is triggered by emotional or physical stress and exhibits a mortality rate of >30% if left untreated (Leenhardt et al., 2012; Napolitano et al., 2014; Priori et al., 2021). Resting electrocardiogram is usually normal and patients develop ventricular arrhythmias during exercise testing (Figure 1). Recently, several hypoactive RyR2 mutations have been described, which are associated with the calcium release deficiency syndrome (Tester et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021). In addition, RyR2 mutations have been implicated in intellectual disability (Lieve et al., 2018) and genetic generalized epilepsy (Yap and Smyth, 2019), which is not surprising given that RyR2 is expressed in the brain (Torres and Hidalgo, 2023).

Figure 1. Typical CPVT electrocardiogram (A). At rest. (B) During exercise testing. Very frequent ventricular extrasystoles, biderectional ventricular couplets (arrow) and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (double arrowheads).

The functional RyR2 channel, consisting of four identical subunits of ∼5,000 amino acids, is organized in discreet structural domains. The transmembrane domain encompassing the Ca2+ permeable pore is located at the C-terminus (residues 4484-4886). The Core Solenoid (CSol, residues 3612-4206) has been described as the gatekeeper of the channel because it is directly associated with the pore-forming region (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016). The N-terminus domain (NTD, residues 1-640), although distant from the pore in terms of both primary and tertiary structure, is essential for RyR2 function regulating both channel opening and closing (Tang et al., 2012; Zissimopoulos et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Seidel et al., 2015; Faltinova et al., 2017; Seidel et al., 2021). The NTD’s dual role in channel gating likely arises from its involvement in separate RyR2 inter-domain interactions due to the extensive and intricate folding of the RyR2 polypeptide chain. Indeed, the high-resolution 3D structures of the RyR1/2 homotetrameric channels (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016) have revealed that the NTD forms an interface with a neighboring NTD (referred to as type I hereafter) and separate intra- and inter-subunit interfaces (referred to as type IIintra and IIinter, respectively) with the CSol.

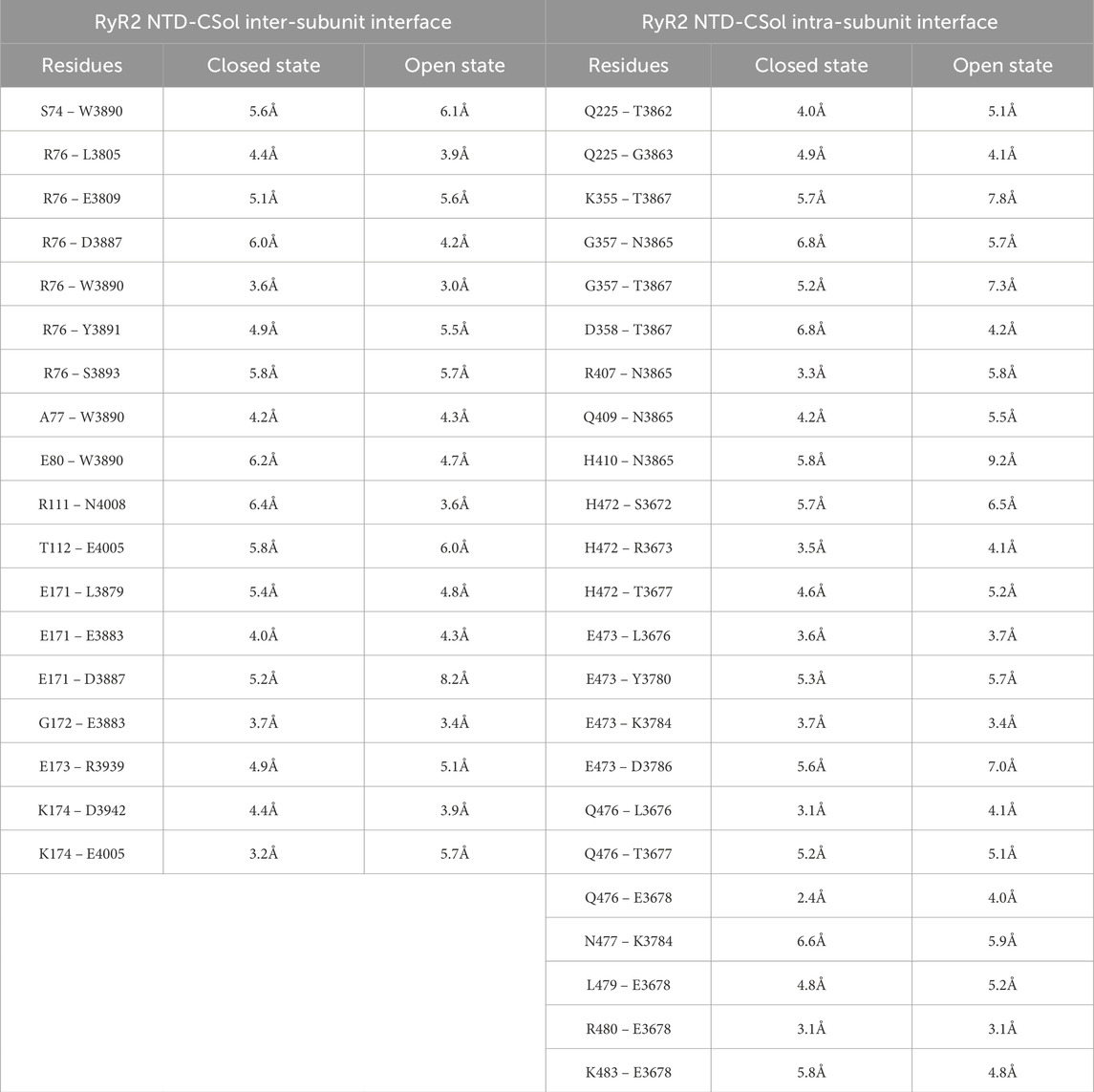

The type II residues that are within 6Å distance from each other and therefore likely to directly participate in RyR2 intra- and inter-subunit NTD-CSol interactions are given in Table 1. RyR2 NTD mutations residing within different inter-domain interfaces are potentially affecting channel function by separate mechanisms. To test this hypothesis, we biochemically and functionally characterized mutations A77T, R169L and G357S, representative type IIinter, I, and IIintra variants, respectively.

Table 1. RyR2 residues at the NTD-CSol inter- and intra-subunit interfaces Atomic distance between listed residues taken from the cryo-electron microscopy structure of RyR2 in the closed (5GO9) and open state (5GOA) (Peng et al., 2016).

2 Methods2.1 MaterialsThe human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cell line was obtained from ATCC® (CRL-1573), mammalian cell culture reagents from Thermo Scientific, Cal-520 a.m. from Stratech, protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete™) from Roche, nProtein-A Sepharose from GE Healthcare, electrophoresis equipment and reagents from Bio-Rad, and the enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit from Thermo Scientific. Mouse anti-cMyc (9E10) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, mouse anti-HA (16B12) from Biolegend, rabbit anti-HA (ab9110) and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase from Abcam, DNA restriction endonucleases from New England Biolabs, Pfu DNA polymerase from Promega, site-directed mutagenesis kit (QuikChange II XL) from Agilent Technologies, CHAPS, normal rabbit IgG, oligonucleotides and all other reagents from Merck unless otherwise stated.

2.2 Plasmid constructionThe plasmids encoding for wild-type RyR2 N-terminus (NT, residues 1-906) tagged with the cMyc epitope, and RyR2 C-terminus (HA-RyR2-CT, residues 3529-4967) tagged with the HA epitope have been described previously (Zissimopoulos et al., 2013; Seidel et al., 2021). Desired missense mutations (A77T, R169L, G357S, R407I) were generated using the site-directed mutagenesis QuikChange II XL kit and appropriate primers as recommended by the supplier. Plasmids encoding for human RyR2A77T, RyR2R169L and RyR2G357S were prepared by replacing a SpeI–BstEII ∼3.8 kb DNA fragment into the WT plasmid. All plasmid constructs were verified by direct DNA sequencing.

2.3 Chemical cross-linkingHEK293 cells were transiently transfected using TurboFect (Thermo Scientific) according to the provider’s instructions. 24 h post-transfection, cells were homogenized on ice in buffer (5 mM HEPES, 0.3 M sucrose, 10 mM DTT, pH 7.4) by 20 passages through a needle (0.6 × 30 mm) and dispersing the cell suspension through half volume of glass beads (425–600 microns). Cell homogenate free of nuclei and heavy protein aggregates was obtained by centrifugation at 1500 g for 5 min at 4°C, followed by a second centrifugation step at 20,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell homogenate supernatant (20 μg) was incubated with glutaraldehyde (0.0025% or 260 μmol/L) for the following time-points: 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 60 min. The reaction was stopped with the addition of hydrazine (2%) and SDS-PAGE loading buffer (60 mM Tris, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% bromophenol blue, pH 6.8). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with AbcMyc (9E10, 1:1000 dilution). Tetramer to monomer ratio was determined by densitometry using a GS-900 Scanner (Bio-Rad) and Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). Tetramer formation was calculated as follows: T = ODT/(ODT + ODM)x100, where ODT and ODM correspond to optical density obtained for tetramer and monomer bands, respectively. Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism software.

2.4 Co-immunoprecipitationHEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with plasmid DNA for HA-RyR2-CT together with cMyc-RyR2-NT constructs using TurboFect. Cells were homogenized on ice 24 h post-transfection, in buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) as described in 2.3 above. Cell nuclei and glass beads were removed by centrifugation at 1500 g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant was incubated for 1 h at 4°C in the presence of 0.5% CHAPS under rotary agitation. Following solubilization and centrifugation at 20,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the insoluble material, the supernatant was incubated at 4°C for 2 h with Protein A-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) and 1 μg of AbHA (rabbit ab9110) under rotary agitation (1 μg of normal, non-immune rabbit IgG was used as negative control). Beads were recovered at 1500 x g for 2 min at 4°C, washed two times with IP buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% CHAPS, pH 7.4) and proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer. A small amount (1/10th) of the IP samples was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with AbHA (16B12, 1:1000 dilution) to assess HA-RyR2-CT expression and immunoprecipitation. The rest (9/10th) of the IP samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with AbcMyc (9E10, 1:500 dilution) to assess the amount of the co-precipitated RyR2 NT construct. The amount of co-precipitated RyR2 NT proteins was determined by densitometry (using GS-900 Scanner and Image Lab software), normalized against the amount of input protein in the lysate and specific binding was calculated by subtracting the non-immune IgG IP signal from the anti-HA IP signal. Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism software.

2.5 Calcium imagingHEK293 cells (∼1 x 105) were seeded on poly-lysine coated glass bottom dishes (MatTek) and transiently transfected with plasmid DNA for full-length human RyR2 using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, cells were loaded with Cal-520 a.m. (8 μM) for 1 h at 37°C and immersed in buffer (120 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM glucose, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) for imaging at 37°C. RyR2-mediated spontaneous Ca2+ release events were monitored using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP5) and LAS-AF software (Leica Microsystems) with the following parameters: ×20 magnification objective lens, excitation at 488 nm and fluorescence emission detected at 500–550 nm, 512 x 512 pixel resolution, 100 msec time interval and scanning speed of 400 Hz. Cells were imaged for 5 min and challenged with 10 mM caffeine after ∼4½ min. Acquired regions of interest representing global Ca2+ environments (typically ∼50 μm2) were selected. A broad range of parametric values was calculated from experimental traces by in house developed MATLAB (MathWorks) based software. Parameters include spontaneous Ca2+ transient amplitude and duration, number of Ca2+ transient events, caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient amplitude (taken as indication of Ca2+ store content) and proportion of oscillating cells (number of cells displaying spontaneous Ca2+ release events relative to the total number of cells responding to caffeine). Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism software.

3 Results3.1 A77T and R169L affect distinct RyR2 structure parametersWe chose to study the R169L type I mutation (Ohno et al., 2015) specifically because it resides within the β8-β9 loop (residues 165-179), which is the primary determinant for RyR2 N-terminus self-association and a key element for channel function (Seidel et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). G357S (Medeiros-Domingo et al., 2009) was selected because it resides within the NTD-CSol intra-subunit contact (Table 1; Figure 2A). A77T was chosen because it lies within the NTD-CSol inter-subunit contact (Table 1; Figure 2B), and it has been implicated in cardiac and neuronal disorders (Yap and Smyth, 2019).

Figure 2. RyR2 residues at the NTD-CSol intra- and inter-subunit interfaces. Images of the NTD-CSol intra- and inter-subunit interfaces generated using PyMol from the RyR2 closed state (5GO9) structure. (A) The locations of residue G357 that is in close apposition to residues N3865 and T3867 on the same subunit, and the G357-N3865 and G357-T3867 distances (in Å) are depicted. (B) The locations of residue A77 on one subunit that is in close apposition to residue W3890 on the neighboring subunit and the A77-W3890 distance (in Å) are depicted.

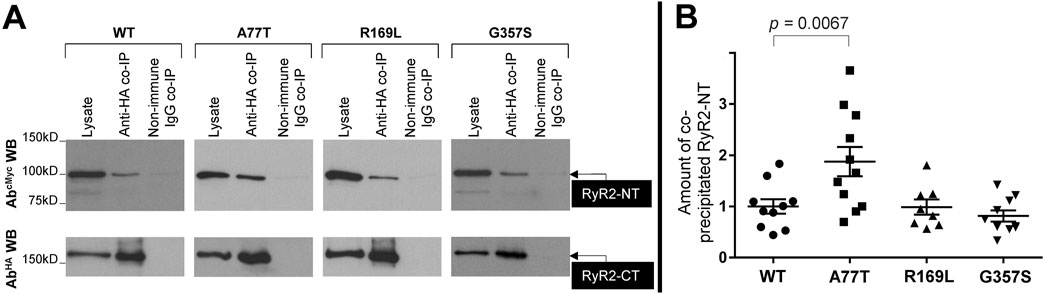

RyR2 NTD tetramerization was assessed by chemical cross-linking. NTWT (human RyR2 residues 1-906, cMyc-tagged), NTA77T, NTR169L and NTG357S were expressed in HEK293 cells and reacted with glutaraldehyde, which creates stable covalent chemical bridges between pre-existing protein complexes, and tetramer formation was analyzed by Western blotting using AbcMyc (Figure 3). Time-dependent formation of a ∼400 kDa band indicating the existence of a tetrameric assembly of ∼100 kDa RyR2-NT protomers (Zissimopoulos et al., 2013) was evident for WT and mutants. As we have recently reported for the R169Q variant (Zhang et al., 2022), the type I R169L mutation significantly reduced tetramer formation compared to WT. In contrast, the type II variants A77T and G357S, which are located away from the NTD-NTD interface, produced tetramers comparable to WT.

Figure 3. A77T, R169L and G357S differentially affect RyR2 N-terminus tetramerization. Chemical cross-linking assays of HEK293 cell homogenates expressing NTWT (RyR2 residues 1-906, cMyc-tagged) or pro-arrhythmic mutants, NTA77T, NTR169L, NTG357S. (A) Cell homogenates were incubated with glutaraldehyde for the indicated time points and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (6% gels) and Western blotting using AbcMyc; monomer (M) and tetramer (T) are indicated with the arrows. (B) Densitometric analysis was carried out on the bands corresponding to tetramer and monomer moieties and used to calculate tetramer formation. Data (n ≥ 8) are normalized for WT and given as mean value ±SEM; statistical analysis was carried out using one-way Anova with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

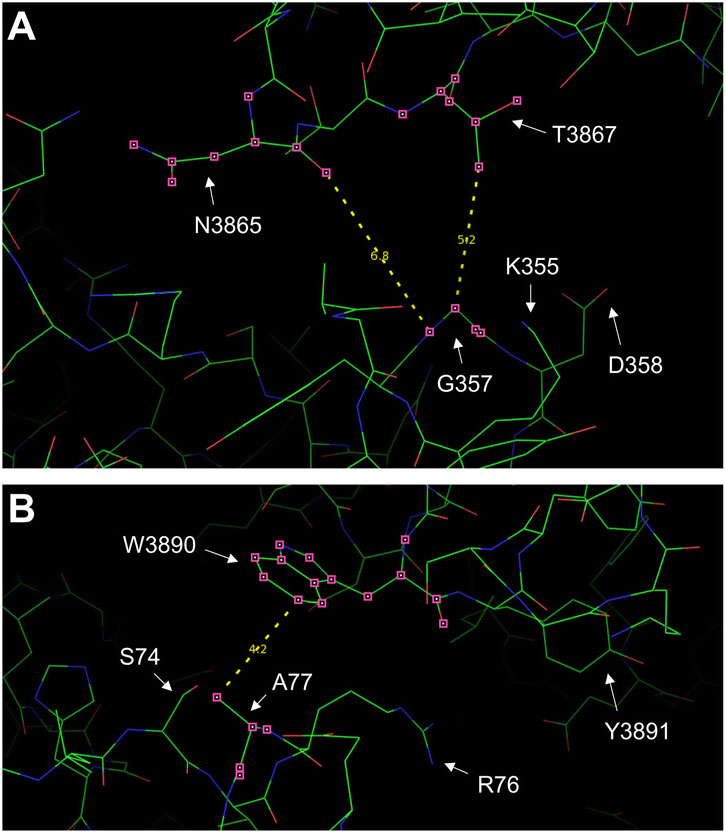

To assess NTD-CSol interactions, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation experiments from HEK293 cells co-expressing NTWT/NTA77T/NTR169L/NTG357S with HA-tagged RyR2-CT (human RyR2 residues 3529-4967). HA-RyR2-CT was immunoprecipitated with AbHA, verified by Western blotting (Figure 4A, bottom panel), while the presence of co-precipitated NT was analyzed by Western blotting using AbcMyc (Figure 4A, top panel). NTWT and mutants were recovered in the HA immunoprecipitate but not in the negative control with non-immune rabbit IgG. Cumulative data (Figure 4B) indicate that immunoprecipitation of HA-RyR2-CT resulted in co-precipitation of NTR169L to levels equivalent to NTWT, which is consistent with our previous finding that deletion of the β8-β9 loop is dispensable for the interaction between the RyR2 N- and C-termini (Seidel et al., 2021). In contrast, the type IIinter A77T mutation significantly enhanced NT interaction with RyR2-CT. Rather surprisingly, the type IIintra variant, G357S, did not alter NT interaction with RyR2-CT. To test whether this is the case with other pro-arrhythmic mutations located within the NTD-CSol intra-subunit contact, we studied the R407I variant (Tester et al., 2012) (Table 1). Similar to G357S, we found no difference in NTR407I interaction with RyR2-CT nor in NTR407I tetramerization compared to WT (data not shown).

Figure 4. A77T, R169L and G357S differentially affect RyR2 N-terminus interaction with C-terminus. Co-immunoprecipitation assays from HEK293 cells co-expressing NTWT or pro-arrhythmic mutants, NTA77T, NTR169L, NTG357S, together with HA-tagged RyR2-CT (residues 3529-4967). (A) HA-RyR2-CT was immunoprecipitated with AbHA from CHAPS-solubilized cell lysates and the presence of co-precipitated NTWT/NTA77T/NTR169L/NTG357S was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (6% gels) and Western blotting using AbcMyc (top). To detect immuno-isolated HA-RyR2-CT, 1/10th of IP samples was analyzed by Western blotting using AbHA (bottom). Non-immune rabbit IgG served as negative control (non-specific binding). An aliquot of HEK293 cell lysate corresponding to 1% of the amount processed in the co-IP assay was included in the gels to assess protein expression. (B) Data summary for NT specific binding (non-immune IgG IP signal subtracted from anti-HA IP signal) following densitometric analysis and normalization to each construct’s respective lysate. Data (n ≥ 8) are normalized for WT and given as mean value ±SEM; statistical analysis was carried out using one-way Anova with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

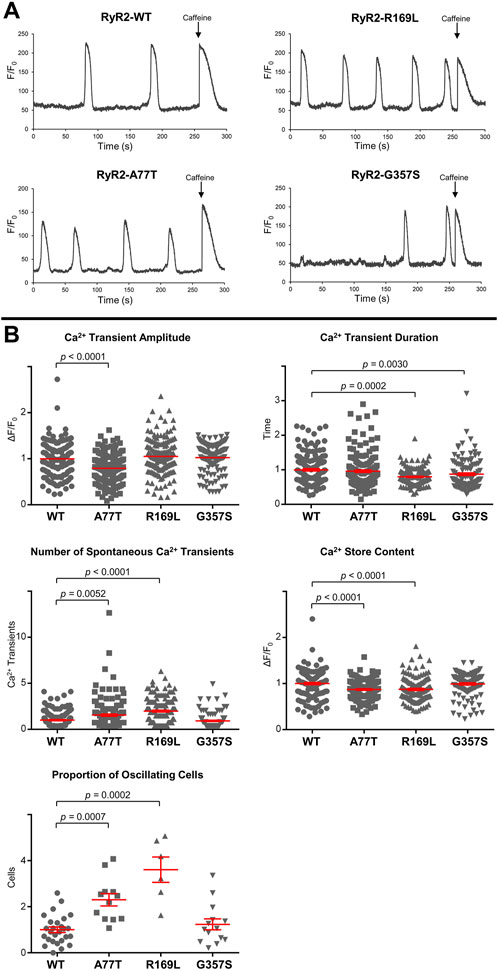

3.2 A77T and R169L alter distinct cellular Ca2+ handling propertiesTo assess RyR2 Ca2+ release properties, we fluorimetrically monitored spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in HEK293 cells expressing RyR2WT/RyR2A77T/RyR2R169L/RyR2G357S using single cell Ca2+ imaging. At the end of the recording, cells were challenged with 10 mM caffeine to verify expression of functional RyR2 channels and estimate the Ca2+ store content. Ca2+ handling parameters of RyR2G357S-expressing cells were similar to RyR2WT. Although Ca2+ transient duration was altered, the proportion of oscillating cells, number of spontaneous Ca2+ transients, and the Ca2+ store content were not significantly different to WT (Figure 5). On the other hand, R169L significantly increased the number of spontaneous Ca2+ transients as well as the proportion of oscillating cells, indicating that this mutation is hyperactive. The amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ transients was unaffected, whereas their duration was smaller in RyR2R169L-expressing cells. The caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient amplitude used as an index of Ca2+ store content was reduced, suggesting that RyR2R169L is a leaky channel. These characteristics are almost identical to another gain-of-function type I variant, R176Q, which we have previously characterized (Seidel et al., 2021). Similar to R169L, A77T also significantly increased the number of spontaneous Ca2+ transients as well as the proportion of oscillating cells, and decreased Ca2+ store content indicating that this mutation is also hyperactive and leaky. However, in contrast to the type I variants R169L and R176Q (Seidel et al., 2021), Ca2+ transient amplitude was smaller, whereas Ca2+ transient duration was unaffected in RyR2A77T-expressing cells (Figure 5). Thus, the type IIinter A77T mutation affects Ca2+ handling parameters differently to type I variants, consistent with the presence of a different underlying molecular mechanism for channel deregulation.

Figure 5. RyR2A77T and RyR2R169L display gain-of-function channel characteristics. Single cell Ca2+ imaging using confocal laser scanning microscopy to monitor spontaneous Ca2+ release transient events. (A) Fluorimetric traces from Cal-520 loaded single HEK293 cells expressing RyR2WT, RyR2A77T, RyR2R169L or RyR2G357S showing spontaneous Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ release induced by caffeine (10 mM) at the end of each experiment. (B) Cellular Ca2+ handling properties including spontaneous Ca2+ transient amplitude and duration, number of spontaneous Ca2+ transient events, amplitude of the caffeine response (Ca2+ store content) and proportion of oscillating cells. Data (for n ≥ 119 cells from n ≥ 6 separate experiments) are normalized for WT and given as mean value ± SEM (shown in red for clarity); statistical analysis was carried out using Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

4 DiscussionIt has long been recognized “that a single mechanism is unlikely to operate in all (RyR2) mutations” (Venetucci et al., 2012). We have very recently suggested that three non-mutually exclusive molecular mechanisms are at play for gain-of-function RyR2 mutations, namely, 1. altered cytosolic and/or luminal Ca2+ activation, 2. altered RyR2 intra- and inter-subunit interactions, and 3. altered interactions with accessory proteins (Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022). Quite often though, different mechanisms are proposed by different laboratories, whereas contradicting results have been reported even for the exact same mutation. In the present study, we investigated alternative molecular mechanisms for RyR2 mutations within the same structural (NTD) domain. Notably, our investigations were informed by the high-resolution RyR1/2 3D structure in the open and closed configuration (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016) (Table 1).

The type I NTD-NTD inter-subunit interface is largely comprised of the β8-β9 loop (residues 165-179) in one subunit closely apposed to the β23-β24 loop (residues 395-402) of a neighboring subunit (Tung et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2016; Seidel et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). We have previously shown that the arrhythmogenic mutation L433P perturbs both RyR2 N-terminus and full-length tetramerization to produce functionally aberrant channels with both hyperactive and hypoactive characteristics (Seidel et al., 2015). Given that leucine-433 is buried within the NTD structure (Kimlicka et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2016), proline substitution is likely to induce local conformational changes indirectly affecting the NTD-NTD inter-subunit interface. More recently, we and others provided evidence that the CPVT mutations A165D, R169Q and R176Q that lie within the β8-β9 loop, disrupt RyR2 N-terminus self-association to produce hyperactive and leaky channels (Xiong et al., 2018; Nozaki et al., 2020; Seidel et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). In this study, we find that the type I R169L variant perturbs NTD tetramerization, whereas it has no impact on the NTD-CSol interaction (Figures 3, 4), in agreement with our previous findings for the R169Q, R176Q and β8-β9 loop deletion mutants (Seidel et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). Strikingly, Ca2+ handling parameters of RyR2R169L-expressing cells (Figure 5) are very much alike our previous observations with the hyperactive R176Q mutation (Seidel et al., 2021).

It is clear from the RyR1/2 3D structures that the CSol serves as the primary transducer of cytoplasmic long-range allosteric signals to the channel domain (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016). It is likely that NTD-NTD and NTD-CSol inter-domain interactions act synergistically to regulate channel gating, as revealed by the high-resolution 3D structure of RyR1-R164C. R164C, a malignant hyperthermia mutation within the β8-β9 loop, produced a localized shift and rotation within the NTD resulting in weaker NTD-NTD inter-subunit interaction (Iyer et al., 2020). This in turn further stabilized the NTD-CSol contact, thus conferring to the channel a conformation between fully opened and closed. We have recently reported that the R420Q mutation enhances NTD-CSol interaction (Yin et al., 2021), however, its effect is indirect because this residue is buried within the NTD structure (Kimlicka et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2016). To certify that altered NTD-CSol interaction is indeed a mechanistic basis of RyR2 deregulation, we sought to characterize arrhythmogenic variants that lie at the NTD-CSol intra- (G357S, R407I) and inter-subunit interfaces (A77T) (Table 1).

Our biochemical studies indicate that the type IIintra G357S and R407I mutations do not affect NTD tetramerization (Figure 3), in agreement with their location on the RyR2 homotetrameric structure (Peng et al., 2016). However, they also do not seem to affect the NTD-CSol interaction (Figure 4), which is rather unexpected given their location at the intra-subunit interface (Peng et al., 2016) (Table 1). It is plausible that type IIintra mutations may result in structural alterations that are beyond the detection limit of our biochemical assays. An alternative explanation is that G357S and R407I (and possibly other type IIintra mutations) cause minimal perturbation to the global RyR2 structure. Notably, the Ca2+ handling properties of RyR2G357S-expressing cells were equivalent to WT (Figure 5), suggesting that this mutation on its own is not sufficient to perturb RyR2 function. Liu et al. reported that the G357S mutation reduced the percentage of RyR2-expressing cells that displayed spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, but it increased fractional Ca2+ release in individual cells (Liu et al., 2017). These findings may be partly due to reduced RyR2G357S protein expression in their experimental setup. On the other hand, Liu and co-workers found no change in the sensitivity to Ca2+ activation and no alteration in the Ca2+ store content (Liu et al., 2017). Similarly, an earlier study by Wangüemert and colleagues reported no differences in the caffeine sensitivity or the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations between RyR2G357S and RyR2WT (Wanguemert et al., 2015), in accordance with our findings. Interestingly, Wangüemert et al. found enhanced caffeine sensitivity and an increase in spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations for RyR2G357S compared to WT, following treatment with forskolin to increase intracellular cAMP levels (Wanguemert et al., 2015). Thus, it seems that an additional trigger in the form of catecholaminergic stress is required for the G357S mutation to produce defective RyR2 channels.

Unlike type IIintra mutations, we find that the type IIinter A77T variant enhances NTD-CSol interaction without affecting NTD tetramerization (Figures 3, 4), which is entirely consistent with its location on the RyR2 homotetrameric structure (Peng et al., 2016). Functionally, A77T produces a hyperactive and leaky RyR2 channel, but affecting different Ca2+ release parameters to type I mutations, R169L and R176Q (Figure 5 and (Seidel et al., 2021), respectively). These findings are consistent with a largely more compact NTD-CSol inter-subunit interface, dominated by the R76-D3887, E80-W3890 and R111-N4008 interacting pairs, in the open compared to the closed RyR2 configuration (Peng et al., 2016) (Table 1). The RyR2 A77T mutation has been reported as a potential cause in a case of adult-onset genetic generalized epilepsy, where the patient never described any cardiac symptoms and had repeatedly normal cardiac investigations including normal exercise stress tests (Yap and Smyth, 2019). However, the patient’s sibling was diagnosed with CPVT, whereas alanine-77 substitution by Val has also been linked with CPVT (d’Amati et al., 2005). Thus, increased RyR2 NTD-CSol inter-subunit interaction may be a mechanism that underpins neurocardiac calcium channelopathies manifesting as CPVT and/or epilepsy.

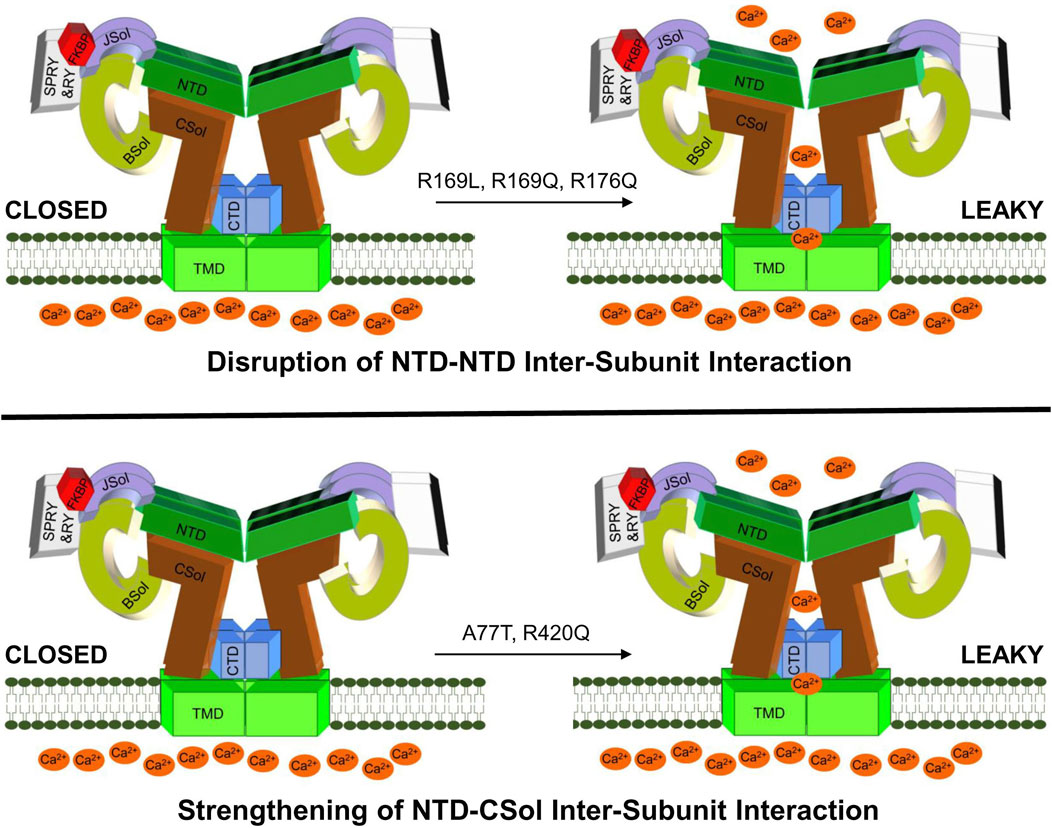

In summary, our findings introduce a novel RyR2 structure-function parameter, namely, the NTD-CSol inter-subunit interaction, in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic cardiac disease. Moreover, they consolidate the role of the NTD self-association in RyR2 pathophysiology. Importantly, we provide compelling evidence that pro-arrhythmic RyR2 mutations have diverse molecular mechanisms of action, even though they may be very closely located within the primary peptide sequence and/or the same structural domain (Figure 6). This may explain the variable efficacy of potential anti-arrhythmics like K201 and dantrolene, reported to be dependent on the precise location of the RyR2 mutation (Connell et al., 2020). Further studies are required to enable a comprehensive classification of RyR2 mutations into distinct groups with discrete structural and functional phenotypes, which may aid future personalized medicine efforts.

Figure 6. A hypothetical model for deregulated RyR2 in CPVT. Drawing depicting proposed altered RyR2 inter-domain interactions due to NTD gain-of-function mutations. CPVT mutations may produce hyperactive leaky RyR2 channels by disrupting the NTD-NTD inter-subunit interaction (e.g., R169L, R169Q, R176Q) or by strengthening the NTD-CSol inter-subunit interaction (e.g., A77T, R420Q).

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributionsYZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. MS: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. CR: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. AB: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. SA: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing–review and editing, Investigation, Methodology. MH: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. FL: Resources, Writing–review and editing. EZ: Data curation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. DP: Formal Analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. SZ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation Fellowship (FS/15/30/31494) and project grant (PG/21/10657) to SZ.

AcknowledgmentsThe patients included in this study from the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de València were genetically characterized with the samples provided by the Biobanco La Fe (B.0000723) and they were processed following standard operating procedures with the appropriate approval of the Ethics and Scientific Committees.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2024.1505698/full#supplementary-material

ReferencesConnell, P., Word, T. A., and Wehrens, X. H. T. (2020). Targeting pathological leak of ryanodine receptors: preclinical progress and the potential impact on treatments for cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 24 (1), 25–36. doi:10.1080/14728222.2020.1708326

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

d’Amati, G., Bagattin, A., Bauce, B., Rampazzo, A., Autore, C., Basso, C., et al. (2005). Juvenile sudden death in a family with polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias caused by a novel RyR2 gene mutation: evidence of specific morphological substrates. Hum. Pathol. 36 (7), 761–767. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2005.04.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Faltinova, A., Tomaskova, N., Antalik, M., Sevcik, J., and Zahradnikova, A. (2017). The N-terminal region of the ryanodine receptor affects channel activation. Front. Physiol. 8, 443. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00443

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Georges, A., Clarke, O. B., Zalk, R., Yuan, Q., Condon, K. J., Grassucci, R. A., et al. (2016). Structural basis for gating and activation of RyR1. Cell 167 (1), 145–157 e117. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.075

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Iyer, K. A., Hu, Y., Nayak, A. R., Kurebayashi, N., Murayama, T., and Samso, M. (2020). Structural mechanism of two gain-of-function cardiac and skeletal RyR mutations at an equivalent site by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 6 (31), eabb2964. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb2964

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kimlicka, L., Tung, C. C., Carlsson, A. C., Lobo, P. A., Yuchi, Z., and Van Petegem, F. (2013). The cardiac ryanodine receptor N-terminal region contains an anion binding site that is targeted by disease mutations. Structure 21 (8), 1440–1449. doi:10.1016/j.str.2013.06.012

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Leenhardt, A., Denjoy, I., and Guicheney, P. (2012). Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 5 (5), 1044–1052. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962027

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lieve, K. V. V., Verhagen, J. M. A., Wei, J., Bos, J. M., van der Werf, C., Roses, I. N. F., et al. (2018). Linking the heart and the brain: neurodevelopmental disorders in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart rhythm. 16 (2), 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.08.025

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, Y., Sun, B., Xiao, Z., Wang, R., Guo, W., Zhang, J. Z., et al. (2015). Roles of the NH2-terminal domains of cardiac ryanodine receptor in Ca2+ release activation and termination. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (12), 7736–7746. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.618827

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, Y., Wei, J., Wong King Yuen, S. M., Sun, B., Tang, Y., Wang, R., et al. (2017). CPVT-associated cardiac ryanodine receptor mutation G357S with reduced penetrance impairs Ca2+ release termination and diminishes protein expression. PLoS One 12 (9), e0184177. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184177

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Medeiros-Domingo, A., Bhuiyan, Z. A., Tester, D. J., Hofman, N., Bikker, H., van Tintelen, J. P., et al. (2009). The RYR2-encoded ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel in patients diagnosed previously with either catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or genotype negative, exercise-induced long QT syndrome: a comprehensive open reading frame mutational analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54 (22), 2065–2074. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.022

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Napolitano, C., Bloise, R., Memmi, M., and Priori, S. G. (2014). Clinical utility gene card for: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 22 (1), 152. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2013.55

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nozaki, Y., Kato, Y., Uike, K., Yamamura, K., Kikuchi, M., Yasuda, M., et al. (2020). Co-phenotype of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy and atypical catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in association with R169Q, a ryanodine receptor type 2 missense mutation. Circ. J. 84 (2), 226–234. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0720

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ohno, S., Hasegawa, K., and Horie, M. (2015). Gender differences in the inheritance mode of RYR2 mutations in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia patients. PLoS One 10 (6), e0131517. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131517

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Peng, W., Shen, H., Wu, J., Guo, W., Pan, X., Wang, R., et al. (2016). Structural basis for the gating mechanism of the type 2 ryanodine receptor RyR2. Science 354 (6310), aah5324. doi:10.1126/science.aah5324

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Priori, S. G., Mazzanti, A., Santiago, D. J., Kukavica, D., Trancuccio, A., and Kovacic, J. C. (2021). Precision medicine in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: JACC focus seminar 5/5. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77 (20), 2592–2612. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.073

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Seidel, M., de Meritens, C. R., Johnson, L., Parthimos, D., Bannister, M., Thomas, N. L., et al. (2021). Identification of an amino-terminus determinant critical for ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel function. Cardiovasc Res. 117 (3), 780–791. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa043

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Seidel, M., Thomas, N. L., Williams, A. J., Lai, F. A., and Zissimopoulos, S. (2015). Dantrolene rescues aberrant N-terminus inter-subunit interactions in mutant pro-arrhythmic cardiac ryanodine receptors. Cardiovasc Res. 105 (1), 118–128. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvu240

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sun, B., Yao, J., Ni, M., Wei, J., Zhong, X., Guo, W., et al. (2021). Cardiac ryanodine receptor calcium release deficiency syndrome. Sci. Transl. Med. 13 (579), eaba7287. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aba7287

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tang, Y., Tian, X., Wang, R., Fill, M., and Chen, S. R. (2012). Abnormal termination of Ca2+ release is a common defect of RyR2 mutations associated with cardiomyopathies. Circ. Res. 110 (7), 968–977. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256560

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tester, D. J., Kim, C. S. J., Hamrick, S. K., Ye, D., O'Hare, B. J., Bombei, H. M., et al. (2020). Molecular characterization of the calcium release channel deficiency syndrome. JCI Insight 5 (15), e135952. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.135952

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tester, D. J., Medeiros-Domingo, A., Will, M. L., Haglund, C. M., and Ackerman, M. J. (2012). Cardiac channel molecular autopsy: insights from 173 consecutive cases of autopsy-negative sudden unexplained death referred for postmortem genetic testing. Mayo Clin. Proc. 87 (6), 524–539. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.017

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Torres, R., and Hidalgo, C. (2023). Subcellular localization and transcriptional regulation of brain ryanodine receptors. Functional implications. Cell Calcium 116, 102821. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2023.102821

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tung, C. C., Lobo, P. A., Kimlicka, L., and Van Petegem, F. (2010). The amino-terminal disease hotspot of ryanodine receptors forms a cytoplasmic vestibule. Nature 468 (7323), 585–588. doi:10.1038/nature09471

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Venetucci, L., Denegri, M., Napolitano, C., and Priori, S. G. (2012). Inherited calcium channelopathies in the pathophysiology of arrhythmias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 9 (10), 561–575. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2012.93

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wanguemert, F., Bosch Calero, C., Perez, C., Campuzano, O., Beltran-Alvarez, P., Scornik, F. S., et al. (2015). Clinical and molecular characterization of a cardiac ryanodine receptor founder mutation causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart rhythm. 12 (7), 1636–1643. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.033

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xiong, J., Liu, X., Gong, Y., Zhang, P., Qiang, S., Zhao, Q., et al. (2018). Pathogenic mechanism of a catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia causing-mutation in cardiac calcium release channel RyR2. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 117, 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.02.014

留言 (0)