Oocyte cryopreservation, or egg freezing, has emerged as a vital reproductive technology, enabling women to preserve their fertility for personal, socio-economic, or health-related reasons. Initially developed for patients facing fertility-compromising medical interventions, oocyte cryopreservation has lately become popular among healthy women seeking to postpone childbirth for career, personal ambitions, or the lack of a suitable partner. This transition not only indicates broader cultural trends in delayed parenthood but also brings about societal benefits, emphasizing the necessity of access to fertility preservation for women.

This study examines the decision-making process influencing women’s decisions to engage in oocyte cryopreservation, including the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) alongside an economic stated-preference framework. This research aims to quantify how women navigate financial restrictions, success probability, and perceptions of infertility concerns. The findings of this study offer essential insights for policy formulation aimed at promoting equal access to fertility preservation technologies, underlining the urgency of addressing the economic and social factors influencing reproductive decision-making.

2 Contextual review of fertility preservation literature2.1 Introduction to oocyte cryopreservationOocyte cryopreservation, also known as egg freezing, represents a significant advancement in reproductive technology, initially developed to preserve the fertility of women undergoing treatments such as chemotherapy, which could jeopardize their reproductive potential (1).

2.2 Technological advances in oocyte cryopreservationThe advent of vitrification (“fast freezing”) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) techniques reignited interest in egg freezing in the early to mid-2000s (2). By 2012, authoritative bodies such as the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (3, 4) and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (5) had removed the experimental status of the procedure, recognizing its safety and efficacy. This paved the way for its broader acceptance and eventual endorsement for non-medical, or ‘social,’ egg freezing, adopted by healthy women who wish to delay childbearing for socio-economic reasons or due to the lack of a suitable partner (1, 3–8).

2.3 Medical vs. social egg freezingOocyte cryopreservation, also known as egg freezing, has two primary objectives: Medical Egg Freezing (MEF), which preserves fertility for medical causes such as chemotherapy, and Social Egg Freezing (SEF), typically employed for delaying parenthood owing to professional ambitions or the lack of a suitable spouse (3, 7, 9).

The distinctions between medical and social egg freezing significantly affect its accessibility, impacting debates on whether social egg freezing should be regarded as preventative healthcare or an elective choice. These disparities influence access, funding, and broader ethical discussions around reproductive rights, autonomy, and healthcare obligations.

The complex terminology associated with egg storage reflects the ongoing debate regarding whether a traditionally non–medical procedure has a legitimate medical justification. A key question in the field of egg freezing is how to distinguish between “medical egg freezing” (MEF) and “social egg freezing” (SEF) (10).

The notion of medical necessity is a complex issue that requires diverse perspectives for a comprehensive understanding. It is subject to varying interpretations by patients, healthcare providers, politicians, and ethicists. The debate centers on whether age–related fertility reductions should be considered medical conditions. Critics argue that egg freezing is a form of preventative medicine rather than necessary medical therapy (11). This discourse, which addresses both MEF and SEF within a unified framework, informs policy discussions that aim to foster reproductive autonomy across diverse socio–economic circumstances (12–14).

2.4 Social egg freezing: managing reproductive options within socio–economic and biological limitationsIn the past two decades, oocyte cryopreservation, particularly SEF, has become increasingly recognized as a choice for women wishing to postpone childbirth for non–medical purposes. Research suggests that SEF frequently encompasses job aspirations, financial limitations, and the lack of a suitable partner, underscoring SEF as a reaction to intricate socio–economic and psychological pressures rather than physical conditions (3–5). This discretionary selection also encompasses broader issues such as reproductive autonomy, and the right of individuals to make their own decisions about their reproductive health. SEF not only ignites discussions on the medicalization of societal problems and the ethical ramifications associated with its use, but also empowers women to take control of their reproductive health, making their own decisions about their genetic heritage, familial relationships, and future parenting (9, 15–20).

SEF enables women to preserve fertility while considering the natural decline in reproductive potential linked to age. Research indicates that women, especially those who are highly educated, gainfully employed, and generally aged 36 to 40, engage in SEF as a proactive strategy to counteract age–related reproductive deterioration (12–14). Prevalent factors for deferring motherhood encompass pursuing career stability, attaining educational objectives, financial security, and searching for a suitable spouse (12, 13, 21). Although SEF adopts a proactive strategy for fertility management, the long–term outcomes remain ambiguous, and apprehensions over the effectiveness of reproductive therapies as women age continue to exist (12, 22, 23).

Biologically, the female reproductive window is considerably more limited than that of males, with a pronounced decrease in fertility potential after age 35. The decline is primarily attributable to the diminished quantity and quality of oocytes, which decreases the probability of successful fertilization and heightens the risks of abnormal embryos and fetal loss (12, 13). SEF provides women the opportunity to mitigate biological limitations, therefore aligning reproductive decisions with their personal, professional, and socio–economic aspirations for future parenting. This validation of their choices through SEF provides women with a sense of control over their reproductive health, acknowledging and respecting their individual circumstances and decisions.

The increasing interest in SEF highlights the intricate interaction of social, economic, and biological variables influencing contemporary reproductive choices. SEF is a substantial and complex alternative in modern family planning, inciting continuous discourse over reproductive rights, social norms, and the ethical and medical ramifications of managing non–medical issues via fertility preservation (2–4, 12, 13, 19–22). Given these factors, SEF is an appealing resolution for women facing age–related infertility challenges, which are intensified by the trend of delayed motherhood. Epidemiological studies indicate that as fertility declines in women’s mid–thirties due to diminished oocyte quality and quantity, the incidence of involuntary childlessness rises, with many women over the age of 45 turning to donor eggs for conception (24, 25).

2.5 Medical risks and health consequences of social egg freezing for mother and childThe medical ramifications for both the mother and the potential child are crucial factors in SEF. The egg cryopreservation process has two main phases: ovarian stimulation and retrieval, and retrieval, followed by cryopreservation. Initially, the oocytes are harvested after ovarian stimulation, then cryopreserved for long–term storage.

The process itself is not without risks: ovarian hyperstimulation, oocyte retrieval, and pregnancy carry specific medical concerns. For instance, women undergoing oocyte retrieval are at risk of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS), particularly when stimulated for egg retrieval (26). Moreover, if a woman opts to conceive later in life, this may pose considerable risks associated with age–related health issues. Women over 45 undergoing In Vitro Fertilization with Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (IVF–ICSI) treatments may encounter problems due to pre–existing chronic health conditions, thereby heightening obstetric risks and adversely affecting delivery outcomes (27). Concerns arise over the ethics of providing fertility–preserving technologies to healthy, fertile women, which may foster erroneous expectations about success rates and medical feasibility in later life stages (28).

The future child’s health is crucial in assessing the risks linked to SEF. Advanced maternal age is associated with increased rates of problems, including premature deliveries and low birth weights, which are more common in the offspring of mothers aged over 40. Research demonstrates that advanced maternal age correlates with an increased likelihood of adverse newborn outcomes, such as preterm delivery and lower birth weights, which may influence long–term child health (29). The dual influence on maternal and child health underscores the need for meticulous evaluation from both medical and ethical viewpoints when assessing the function of elective egg freezing in fertility preservation and delayed parenthood.

2.6 Critiques, societal implications, and ethical disputes contextualizing social egg freezingInitially conceived as a medical procedure, egg freezing has become more popular among healthy women desiring reproductive autonomy, raising questions over its categorization, ethical considerations, and matters of public funding (15, 17, 30). SEF is frequently perceived as addressing socio–economic pressures rather than strictly medical issues. Critics argue that offering a medical solution for social challenges—such as career demands and gendered labor market expectations—reflects a “medicalization” of social problems, where individual medical procedures are applied to fundamentally non–medical issues (3, 5, 31–34). Critics propose alternate strategies, including supportive family policies, cultural transformations, and public health initiatives, that could more effectively tackle the structural factors contributing to delayed childbearing (34).

The binary classification of egg freezing into ‘medical’ and ‘social’ categories has oversimplified the complex motivations for the procedure. This oversimplification raises questions about its suitability for regulatory and funding purposes. Van de Wiel (35) argues that this classification fails to fully capture the diverse reasons behind women’s choice of SEF, while Pennings (16) suggests that the ‘social’ label implies that SEF is seen as a preference rather than a necessity. The merging of medical and elective procedures complicates the ethical landscape, making the distinction between these categories problematic, if not impractical. However, the distinction between MEF and SEF continues to have a significant impact on regulatory policies and funding decisions worldwide (15, 17, 30, 35). It is crucial that we develop a more nuanced understanding of SEF to address the ethical complexities in reproductive health.

Advocates of SEF view it as a tool that can significantly enhance women’s autonomy, giving them control over their reproductive timing and helping them overcome the biological constraints that often put them at a disadvantage compared to men in terms of fertility (9, 10, 20). This perspective supports SEF as a legitimate form of reproductive control, arguing that it strengthens women’s autonomy against cultural pressures that may restrict their reproductive choices. The discussion around SEF’s classification underscores the ethical complexities associated with its use and influences policy debates and the availability of this reproductive technique in various socioeconomic contexts (3, 16, 31, 32, 35). The impact of SEF on women’s autonomy is a significant step towards promoting gender equality in reproductive health.

2.7 Ethical implications and counselling considerations in elective oocyte cryopreservationThe rapid advancement of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has sparked considerable ethical arguments, a topic thoroughly examined in the literature (36).

The American Society of Reproductive Medicine’s Ethics Committee has deemed planned oocyte cryopreservation ethically acceptable, highlighting its advantages for social equity and women’s reproductive autonomy (37). The first successful birth in the U.S. using vitrified human oocytes was reported in 2013 (38). In France, oocyte vitrification was legalized under the French Bioethics Law of 2011, though it continues to be a subject of debate (27, 39, 40). Meanwhile, the National Bioethics Council in Israel has recommended oocyte cryopreservation to counteract age–related fertility declines (41), whereas in EU countries like Austria, egg freezing for social reasons is currently prohibited but remains a controversial issue (42). While the practice of freezing oocytes for cancer patients and others with decreased fertility is generally viewed positively from both medical and ethical perspectives, extending this option to healthy women for the reasons stated above introduces new ethical debates (36, 43). SEF generates a multitude of ethical considerations, including commercial exploitation, the medicalization of reproduction, the autonomy of women, idealized conceptions of the ideal time to become pregnant, the repercussions of egg freezing on gender disparities, and adherence to professional standards (13, 44, 45). Ethical considerations encompass a comprehensive evaluation of the advantages, disadvantages, costs, and ramifications necessary to guarantee the continued efficacy and safety of the procedure (13, 45).

The benefits that elective egg storage provides to women and its contribution to gender equality are emphasized by proponents of the practice. Many women perceive egg freezing as a method to temporarily suspend their biological cycles, thus safeguarding them against age–related fertility concerns and granting them reproductive autonomy and the potential to conceive biological offspring. Additionally, by freezing oocytes at an earlier stage, the probability of genetic abnormalities developing in offspring may be reduced, this risk increases as the age of the mother increases (44, 46).

Conversely, ethical objections to fertility preservation for non–medical purposes highlight the potential for cryopreserved oocytes to provide illusory optimism for future conception, thereby prompting women to postpone motherhood. A delay may elevate hazards related to late pregnancy for both the mother and child, along with potential repercussions for the child’s psychosocial development stemming from the parent’s older age. Additionally, the fact that many women who opt for SEF ultimately do not utilize their stored oocytes serves as a further critique of the practice (13, 45).

An important counseling point often raised by patients concerns the optimal timing for using SEF. Historically, the typical age for egg freezing or vitrification has ranged from 35 to 38 years (37, 47). Generally, there are two prevailing philosophies regarding SEF. On one hand, experts recommend not delaying the procedure, as older oocytes are less likely to lead to a successful pregnancy due to age–related decline and an increased likelihood of chromosomal aneuploidy. On the other, there is a caveat against utilizing this method at a young age when there is still a possibility that the patient may ultimately not need to use the preserved oocytes at all.

2.8 Family planning and oocyte cryopreservationThere has been a significant increase in the quantity of fertility centers worldwide since 2012 that provide elective oocyte cryopreservation (14). Concurrently, a growing proportion of women are choosing to delay the onset of reproduction due to societal considerations.

The dynamics surrounding family planning have undergone substantial transformations in tandem with the shifting roles of women in recent decades. There has been a significant rise in the average age at which women give birth to their first child worldwide (46, 48). Higher education, professional aspirations, financial implications, and changes in social norms and interpersonal connections have all contributed (49, 50). Conversely, postponing parenthood may have an adverse impact on the reproductive capacity of women, a consequence that is frequently unavoidable rather than elective. Involuntary childlessness can be psychologically stressful (51). Female reproductive potential inevitably and irreversibly declines after the age of 37, with oocyte quantity decreasing by a factor of two exponentials (52). Furthermore, it has been observed that the integrity of chromosomes and the quality of ova produced decline in significance beyond the age of 35. Advanced maternal age is a significant risk factor for early miscarriage, with the risk increasing to 51% for ages 40–44 and peaking at 93% after age 45 (53). The success rates for in vitro fertilization (IVF) are around 30% for women under 35, however, these rates decline significantly after this age, with almost no chance of a live birth using their own eggs for women over 45. It’s important to note that alternative methods like adoption or IVF with donor eggs may not be suitable for many women, especially those seeking a genetic connection to their child. These methods might encounter several challenges, including age–related constraints (54).

2.9 Behavioral determinants and predictive factors in oocyte cryopreservation decisions: a theory of planned behavior approachThe Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (55–57) provides a systematic framework for comprehending intentions, which are significant indicators of behavior. Intentions concerning oocyte cryopreservation stem from a confluence of various factors, including personal characteristics, emotions, intellect, values, and in general attitudes, sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, familial status, educational attainment, and income, as well as the powerful influence of society, including culture, political environment, and social norms (58–60). Behavioral aphorisms represent the consequences individuals link to fertility–related choices, whereas normative beliefs relate to the perceived degree of society’s endorsement of reproductive alternatives, particularly cultural expectations on cryopreservation. Control beliefs include perceptions of the circumstances that either promote or obstruct the choice to freeze oocytes.

A critical aspect of TPB is the concept of subjective norms, which refers to an individual’s perception of psychological support or social pressure from their close social circle to either pursue or avoid a specific behaviour, such as oocyte cryopreservation. While subjective norms may not consistently reflect actual societal perspectives, they considerably influence decision–making, with favorable subjective norms enhancing the probability that a person would opt to cryopreserve oocytes (58, 61).

Another crucial component is perceived behavioral control, which refers to an individual’s evaluation of the complexity or ease of executing the behavior. How a woman perceives the cryopreservation process—whether it is within her control and accessible or challenging and costly—affects her intention to proceed, as subjective evaluations of feasibility strongly influence intentions (58, 61).

To gain a precise understanding of attitudes toward cryopreservation, it is necessary to collect data on various influential factors through comprehensive questionnaires that analyze attitudes, beliefs, and preferences. The TPB–aligned questionnaires in this study aim to comprehensively evaluate many factors affecting oocyte cryopreservation intentions. These factors include emotional responses to potential infertility, which frequently reflect values, general attitudes, worries, risk aversion, resource constraints, and social norms. Factors related to life stages, including age, education, income, religion, and family status, are assessed for their influence on decision–making. Factors such as financial expenses and the assessment of utility, which encompasses both private and social advantages, further influence an individual’s intentions about cryopreservation (62).

2.10 Cost–effectiveness and informed decision–making in social egg freezingElective oocyte cryopreservation is a decision that should not be taken lightly. It requires careful consideration and is typically guided by a multidisciplinary team, including an embryologist, fertility expert, and psychologist or counselor. Their role is to help women make informed decisions by understanding the procedure’s risks, benefits, and associated costs. This involves discussions on success rates, potential long–term health implications, statistics on offspring conceived from cryopreserved oocytes, the duration of egg storage, and the importance of signing an informed consent document (2, 13, 63, 64).

It’s important to note that the use rate of frozen oocytes is relatively low, with studies showing a range of 6% to 15% from a cost–effectiveness perspective (27, 41, 65–68). This underscores the need for careful consideration of the economic aspects of elective oocyte cryopreservation, ensuring that resources are used efficiently. Success rates tend to be higher when women opt for oocyte vitrification at a younger age because fewer vitrified oocytes are required to achieve a live birth. Paradoxically, however, younger women are less likely to use their vitrified oocytes due to a greater probability of finding a partner and conceiving naturally later on. Van Loendersloot et al. (69), Hirshfeld–Cytron et al. (70), Garcia–Velasco (71) Mesen et al., and Devine (72, 73) suggest that oocyte cryopreservation would be cost–effective if at least 50–60% of women actually use their vitrified oocytes. On the other hand, other scholars (74–76) contend that a 50% utilization rate may be excessively optimistic. They suggest that women at a higher risk of becoming prematurely sub–fertile—because of factors like ovarian endometriosis, ovarian surgery in the past, or personal circumstances that prevent them from getting pregnant—are more likely to use their vitrified oocytes. Oocyte freezing is probably more economical for these women.

2.11 Social benefit and public fundingThe discourse on societal benefits is crucial when evaluating public financing for procedures such as oocyte cryopreservation, presenting the challenge of who ought to bear the costs.

‘Elective freezing,’ ‘non–medical freezing,’ or ‘social freezing’ (as opposed to ‘medical freezing’) is currently a privilege mostly enjoyed by women who can afford the costs of ovarian stimulation medicines, medical procedures, vitrification or slow freezing, and storage fees (77).

While the right to propagate is commonly recognized as a liberty right, it is not typically considered a claim right (78). This means that although women may elect to cryopreserve their oocytes, they do not have a legitimate claim on societal resources to subsidize it. However, many Western countries offer healthcare coverage for a certain number of ‘standard’ IVF cycles to ensure equal access, and several US states mandate infertility insurance coverage. This suggests that, in these jurisdictions, the right to reasonable healthcare extends to fertility treatments (79).

The question arises: should countries with publicly funded IVF extend coverage to social freezing? If oocyte cryopreservation is an accepted method to counter infertility and fertility treatment is covered by public healthcare, should social freezing also be included in public healthcare or mandated insurance coverage, or is there a significant distinction between ‘regular’ IVF and IVF with previously stored oocytes? The challenge in this assessment is that elective oocyte freezing involves two distinct phases: initially, ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval, cryopreservation, and storage, and later (often years afterward), the thawing and fertilization of the cryopreserved oocytes. In the first phase, women who opt for social freezing are healthy and are seeking a procedure that results in stored oocytes that may or may not be utilized, depending on their life circumstances. The second phase is medical intervention. Women seeking elective oocyte cryopreservation differ from other IVF patients in a critical way: they are not infertile, which is often a prerequisite for state–funded IVF cycles in many countries.

The term ‘elective freezing’ highlights that oocyte cryopreservation by healthy women is similar to other elective medical interventions, like cosmetic surgery, which typically do not provide direct therapeutic benefits (unless psychologically). This raises questions about why society should fund what some might consider merely a convenience. However, while the distinction between medical and social interventions often guides reimbursement policies, there are many exceptions, particularly in reproductive health, such as elective abortion, contraception, and pregnancy care, which are treated as medical interventions deserving of coverage despite pregnancy not being a disease (80).

Furthermore, social freezing may be conceptualized as a type of anticipatory medicine in which women reserve eggs in anticipation of potential future reproductive difficulties. While this preventative strategy may not yield immediate therapeutic advantages, it does possess the potential for future therapeutic benefits, which may support its inclusion in healthcare coverage. If public healthcare covers IVF cycles using fresh but aged oocytes or donor oocytes for women, it follows that the use of their cryopreserved oocytes should also be reimbursed. Consistency in treatment would acknowledge the ethical and practical advantages of using freshly aged oocytes from the woman herself instead of utilizing donor oocytes. These considerations support the idea that compensation for elective cryopreservation should be comparable to that for “regular” IVF treatment when viewed as a unified entity with IVF treatment. However, a more nuanced policy approach may be needed given the separate steps of the process and the possible absence of causality between the initial storage phase and the subsequent treatment phase. Options might be full coverage or a cash or service refund for the first phase in the event that the woman returns for the second.

2.12 International regulatory landscapeResearch conducted by the European IVF–monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and its Working Group on Oocyte Cryopreservation highlights considerable variability in the regulatory and financial frameworks governing egg freezing across forty–three countries. The data indicates that legal frameworks and financial mechanisms vary significantly, illustrating diverse national strategies for managing and promoting this technology (81, 82).

Over the past thirty years, there has been a noticeable increase in the postponement of motherhood among women of reproductive age in several Western nations. This trend is primarily attributed to a variety of factors, including improved educational and professional opportunities, caregiving responsibilities, financial challenges, the pursuit of economic security, the absence of a suitable partner, and the aspiration to establish a stable home environment. Additionally, the widespread availability of contraception and the belief that individuals are not yet ‘ready’ for motherhood further contribute to this shift (83).

When it comes to the funding of medical and SEF, policies vary significantly. For instance, nations like Israel, the United States, and certain European regions provide either partial or full coverage for MEF. However, SEF is often excluded from public funding due to its optional nature. In Israel, public funding for MEF is allowed through the national health insurance system, but SEF is limited to private healthcare plans. This distinction underscores the emphasis on medically necessary applications over optional procedures (11, 34, 82).

2.13 IsraelUnder the Israeli National Health Insurance Law (1994), which ensures the accessibility and financial support of numerous technologies, including IVF, the funding and utilization of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) are regulated in Israel. Egg donation is an example of an ART that is regulated by specific laws (10), as opposed to directives from the Israeli Ministry of Health regarding other ARTs. Two directives specifically dedicated to regulating oocyte vitrification were issued by the Israeli Ministry of Health. The first directive (84) stated that vitrification should no longer be considered experimental. The subsequent directive (85) detailed the indications and conditions that justify the use of egg freezing, allowing both MEF and SEF.

The Israeli National Health Insurance Law (1994, section 6 amended in 2011) outlines chemotherapy and radiation therapy as justifiable indications for funding fertility preservation methods such as egg–freezing, embryo freezing, and ovarian tissue freezing (children, adolescent, and women patients). The Israeli Ministry of Health (86) also provides similar indications based on recommendations from the Israeli National Council for Gynecology, Neonatology, and Genetics. In 2011, the Ministry published additional medical conditions under which egg freezing will be performed, extending indications for medical fertility preservation beyond cancer patients to include other conditions and procedures that pose a risk to future fertility.

While MEF and SEF are regulated and performed in Israel, the funding guidelines differ. Fertility preservation is fully covered by the Israeli National Health Insurance for medical indications (87). Women undergoing chemotherapy or radiation do not incur costs for fertility preservation for up to two children (85). For increased risk of early amenorrhea, funding for MEF is limited to women under the age of thirty–nine and to a maximum of four treatment cycles or twenty retrieved eggs—whichever comes first. If the woman is a carrier of Fragile X Syndrome, funding extends to six cycles or forty eggs (88). Funded storage is limited until the birth of two children or until the woman reaches the age of forty–two (whichever is earlier).

In contrast, SEF is not covered by the Israeli National Health Basket. However, one Health Maintenance Organization, “Meuhedet,” offers partial subsidization for women with supplemental medical insurance (89). The usage of frozen eggs later can be funded as part of the public funding scheme for IVF, with every woman aged eighteen to forty–five entitled to almost unlimited funded treatment up to the birth of two living children, without conditions based on familial status or sexual orientation.

In 2014, some moderate restrictions were issued concerning the provision of IVF, such as reassessment after eight unsuccessful cycles (90). SEF regulations allow healthy women aged thirty to forty–one to freeze eggs, limiting the procedure to four treatment cycles or twenty retrieved eggs (whichever comes first) with implantation of fertilized eggs allowed until the age of fifty–four. Eggs can be stored for five years with an option to extend.

These differences between MEF and SEF can be seen as establishing a hierarchy, prioritizing MEF over SEF in terms of funding and regulatory support.

Regarding Jewish religious tradition and practice, egg freezing has been embraced by Israel’s religious establishment, spanning various local religious factions. The PUAH Institute, established in 1980 to align ART implementation with Jewish law (halacha) (91, 92) has strongly supported egg freezing, particularly advocating for SEF among single Orthodox women and providing support in IVF clinics. PUAH’s official stance on egg freezing suggests that SEF can aid women who began childbearing later in life but wish to establish a family (93) (PUAH Institute 2018). The Institute also extends its support to Jewish American communities, offering educational, financial, and emotional assistance for those utilizing ARTs. Consequently, rabbis across various religious communities now encourage single Orthodox women in their late thirties to freeze their eggs (94).

In Judaism, where reproduction is a central tenet, innovative reproductive technologies that facilitate the growth of the Jewish population are widely accepted (95–97). Jewish women who opt for egg freezing are often seen as committing to the Jewish maternal imperative—the religious and social expectation for Jewish women to engage in “reproducing Jews” (94), “embodying (Jewish) culture” (98), and “birthing a mother” (99). This imperative is particularly prominent in Israel, described as the “land of imperative motherhood” [98[, where the state supports Jewish women’s reproduction through numerous subsidized fertility services. Israeli women and couples may even undergo various forms of “bio–scrutiny” to ensure they create the desired type of Jewish family in terms of both physical and genealogical heritage (100).

2.13.1 The Jewish maternal imperativeChildbearing holds a revered place in Judaism, where both ancient and modern texts view it as essential to personal and social identity and vital for the continuity of the Jewish people, giving it a collective moral significance (95, 101). While the commandment to “be fruitful and multiply” traditionally applies to men, Jewish identity is passed matrilineally, making childbearing a significant responsibility and life goal for Jewish women. Most rabbis assert that an infant’s Jewishness depends on the mother’s religion—emphasizing the womb over genetic lineage.

However, recent anthropological studies highlight the importance of genetics in contemporary Jewish reproduction, underscoring the preference for using one’s own eggs (95, 98, 99, 102–108). In Israel, childbearing is not only critical for nation–building (106, 107) but also considered a primary form of women’s political participation (109–114), resulting in Jewish women in Israel having more children on average than those in any other industrialized nation. Childlessness carries a significant stigma, often overshadowing other life achievements (99).

Viewing “the right to parenthood” as a fundamental human right (95), childless women in Israel often describe their condition as akin to a “serious illness,” with infertility perceived as a “final extinction” for families of Holocaust survivors (95). The enthusiastic reception of all forms of ARTs since the early introduction of IVF (95, 97, 115, 116) supported by the world’s most generous state–backed IVF policy (117), illustrates the deep commitment to the Jewish maternal imperative. Despite the intense physical and emotional toll of these procedures (118), many women persist with these invasive treatments, viewing them as pathways to fulfillment and happiness (119).

2.14 Future research directionsFurther research is necessary to deepen the understanding of the long–term societal, health, and familial impacts of oocyte cryopreservation. Emerging technologies, demographic shifts, and evolving societal attitudes towards delayed parenthood present significant areas for study. Longitudinal research on the health outcomes of children born from cryopreserved oocytes will provide valuable insights into potential long–term effects. Additionally, studies on the psychological and social impacts of egg freezing, particularly for women who eventually do not use their stored oocytes, will contribute to a holistic understanding of this practice. Investigation into cost–effectiveness, alongside policy and regulatory impacts across various regions, will also aid in formulating equitable, accessible, and sustainable fertility preservation strategies.

2.15 ConclusionOocyte cryopreservation is a transformative option in reproductive healthcare, empowering women with increased control over family planning and allowing them to navigate the intersection of career, personal goals, and biological limitations. As healthcare policies and societal norms continue to evolve, it is crucial to balance access, ethical considerations, and cultural influences to support reproductive autonomy. This study underscores the importance of establishing policies responsive to the multifaceted needs of women, contributing to a framework that respects both individual choices and broader societal impacts.

3 Methods3.1 The theoretical frameworkThrough the integration of the economic stated preference framework and the TPB, this study seeks to investigate the motivations underlying cryopreservation. The TPB (55–57) is employed to underscore the correlation between micro and macro–level intentions and behaviors. Fertility behavior is perceived as the result of a decision–making process that weighs the advantages and disadvantages of potential courses of action within the micro context with consideration for individual characteristics and variables. These factors include subjective norms (an individual’s perception of psychological support or social pressure) and perceived behavioral control (how easy or difficult an individual perceives it is to perform the behavior or reach the intended goal), which both significantly influence intentions and behaviors (62). The approach uses questionnaires to assess elements such as beliefs, attitudes, and social norms (for example, norms concerning the appropriate age for childbearing), as well as wider national or cultural values, and the economic and political environment. Furthermore, the TPB is evaluated at the macroeconomic level (59, 120), specifically regarding how governmental entities determine whether to subsidize or finance oocyte cryopreservation.

3.2 The empirical modelInsights into the preferences and evaluations of patients regarding various facets of healthcare procedures are critical for program development and assessment. By incorporating patient preferences into policy decisions concerning clinical practices, licensing, and reimbursement, substantial improvements can be achieved. Enhancing the alignment of healthcare policies with patient preferences has the capacity to elevate satisfaction levels with clinical interventions and public health undertakings, thereby potentially bolstering the overall efficacy of healthcare processes (121, 122).

Economists define two main approaches to measuring preferences: revealed and stated (123). Revealed preferences are inferred from actual observed behaviors in the market, identified through complex econometric methods used by researchers. In contrast, stated preferences are gathered through surveys that allow researchers to manipulate how preferences are elicited.

Stated–preference methods are categorized into two main types: Methods that utilize rating, ranking, or choice designs (used individually or in combination) to quantify preferences for various attributes of an intervention. These methods, commonly referred to as conjoint analysis (CA), discrete–choice experiments, or stated–choice methods, are designed to explore the trade–offs between different properties of a product and their influence on user preference (124–126).

3.3 Conjoint analysis in health care studiesThe use of CA in healthcare research has increased substantially (127, 128), with Clark et al. (129) and De Bekker–Grob et al. (130) providing exhaustive literature reviews. CA is a method that, based on the evaluation of a set of values (131–134), derives part–worth values for individual attributes from a total score for a product or service composed of multiple attributes. This methodology is especially well–suited for quantifying preferences for non–traditional market products and services or those in sectors where market options are limited by regulations or legal restrictions, such as healthcare (135). CA has demonstrated efficacy in preference measurement across a multitude of health applications (89, 128, 136–141), and its applicability transcends healthcare interventions. It is increasingly used to understand preferences related to health–related quality of life and to evaluate patient–reported outcomes of different health conditions (142, 143). Licensing authorities have also shown interest in CA as a tool for assessing patient willingness to undergo innovative treatments that may offer enhanced efficacy (144).

CA facilitates decision–making processes for patient participation (145, 146), supports shared decision–making (147), aids in clinical decision–making (148), and helps elucidate how various stakeholders value healthcare outcomes (149). Furthermore, CA can evaluate the relative importance of one or more attributes of a product or service and assess how individuals make trade–offs between these attributes. This process identifies the user–required exchange rate between units of an attribute (149).

CA studies present hypothetical scenarios to participants, which involve attributes of a product or service that are assigned to different degrees of importance. Respondents are then asked to rank these services, rate them, or choose between paired attributes. While people frequently make decisions involving exchange and substitution in their daily lives, they are rarely required to explicitly rank and rate attributes as part of their routine decision–making. This paper contributes to the development and application of the pairwise ‘choice’ approach in the decision–making process, which compares two indirect utility (benefit or satisfaction) functions. Participants in the study are asked to make a series of pairwise choices, selecting the option that offers the higher level of utility in each comparison.

3.4 Study design and methodsCA techniques used to elicit preferences helped determine the relative importance that individuals attribute to different attributes of a particular health product or service (135). By analyzing how participants express their inclinations towards various attributes of the product or service, CA enables the evaluation of the practicality, or implicit worth, of those particular elements of the healthcare intervention. The analysis of CA in this paper is grounded in the methodology described by Ryan (150).

For this research, a structured CA questionnaire was developed: Participants were presented with hypothetical scenarios with various attributes crucial to cryopreservation and asked to make pairwise choices between two options. The initial set of attributes and their levels were defined based on a literature review. Appendix 1, Table 1, summarizes the attributes and levels included in the CA study. Each respondent was shown a series of 10 scenarios, with Option A having fixed attributes and Option B varying in each scenario, thus forming a total of 10 pairwise choice questions. An example of one such pairwise choice is detailed in Table 2 of Appendix 1.

3.5 Experimental design & methods3.5.1 Data collectionData was gathered by surveys conducted among women from the general public. The study respondents were drawn from a pool of participants recruited through a survey company and participated voluntarily without any monetary compensation. The study design was cross–sectional with a single data collection point. The survey company had sole access to the participants’ data. Each participant was given a personal code so that the personal information was not known to the researcher conducting the study. Participants were given detailed information on oocyte cryopreservation prior to completing the survey. This included explanations about the reasons for considering oocyte cryopreservation, such as medical conditions like cancer, military service risks, and high–risk occupations, as well as the biological background regarding a woman’s egg reserve and the benefits of egg freezing (the Questionnaire is presented in Appendix 2).

3.5.2 Questionnaire designThree data–gathering stages were used to construct the survey and carry it out:

Preliminary Stage: In the preliminary stage, items to be included in the research questionnaires were identified, using in–depth interviews with five fertility experts and three potential candidates for oocyte cryopreservation. The time frame for the preliminary interviews was six months. The questionnaires were initially constructed on the basis of content analysis of interview results.

Pilot Study: After completing the first version of the questionnaires (based on the preliminary stage findings), a pilot study was conducted, with 15 participants. The pilot study aimed at assessing the difficulty and clarity of the questionnaire and the respondents’ willingness to respond to the items in it. This pilot study, which included face–to–face interviews conducted by the researcher, provided the participants with detailed information about cryopreservation and enabled the presentation of relevant information in a supervised manner as it gathered responses to the different factors. The time frame for the pilot study was three months.

Main Survey: Based on the findings of the pilot study, the research questionnaires were developed for the survey population. The population sample consisted of Israeli Jewish women aged 18–65, from four major urban centers: four large cities in four major population regions in Israel: Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, and Beer Sheba. First, the survey company made contact by telephone, then questionnaires via Google Docs were sent to respondents who agreed to participate in the study. Every respondent confirmed her participation by digitally signing an informed consent form. The time frame for the main survey was 3 months.

Out of 807 questionnaires distributed, 94 were eliminated because they had invalid or missing data and 148 were eliminated because of inconsistency i.e., according to internal (theoretical) consistency tested through the CA technique (See Section 4.3 Methodological issues addressed). The final sample consisted of 565 participants.

3.5.3 Ethical considerationsThe participants, all 18 years of age and over, were given a page describing the goals of the study, guaranteeing anonymity, and explaining the possibility of terminating their participation at any time. Participants were asked to sign an informed consent form before answering the questionnaire. Anonymous, self–administered questionnaires were filled out without interventions by investigators. In the cover letter attached to the questionnaire, the participants were informed that data collection and analysis would be kept fully anonymous, and their personal information would be fully protected, all answers would be kept confidential, processed statistically, and used for scientific research only.

The participants were free to decide whether or not to participate. Each participant provided signed informed consent to participate in the study. Ariel University Ethics Committee approval number: AU–SOC–YB–20141230.

4 Data analysisSAS Vs 9.4 was used for the analysis.

Continuous variables were presented by mean and standard deviation, or median and inter quantile range. Categorical variables were presented by (N%).

In market research, CA is a statistical method utilized to determine how individuals make purchases and what qualities they genuinely value in services and products. In this type of survey, participants are provided with a series of alternatives or products containing distinct qualities at varying degrees. They are subsequently requested to select their preferred option or arrange them in ranked preference. The basic idea is to dissect and analyze the options in order to ascertain which attribute combination has the greatest impact on consumer choice.

The premise of this methodology is that a product’s qualities (e.g., price, quality, brand, features) characterize it, and that the consumer’s assessment of the product is a composite of the assessments of each individual quality or brand attribute. CA can distinguish the relative significance of attributes that influence a consumer’s choice or decision by presenting them with a variety of product configurations comprised of distinct attribute combinations.

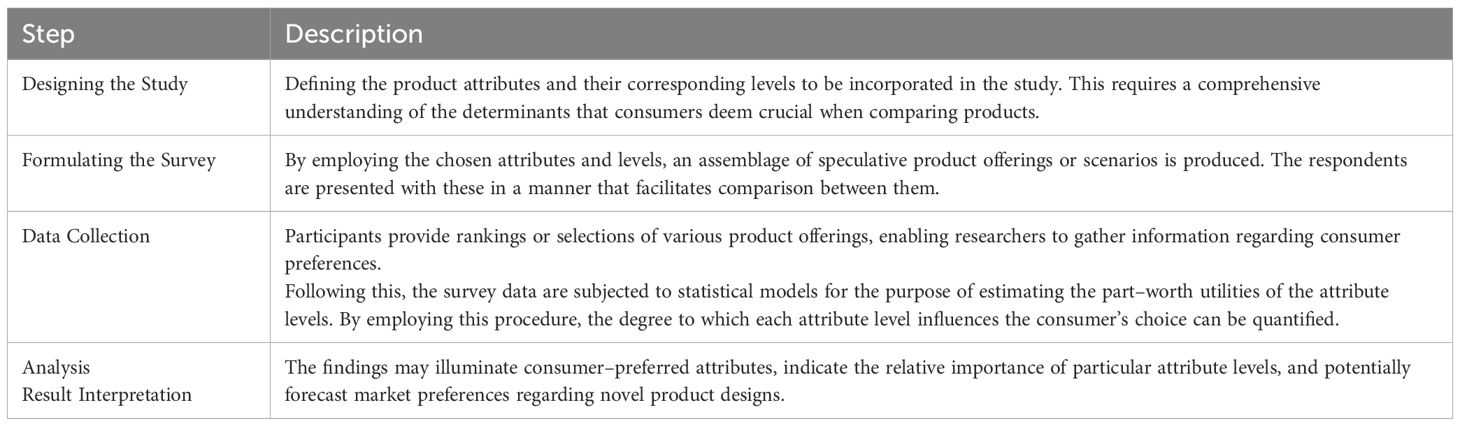

A conjoint analysis is performed as follows in Table 1:

Table 1. Steps in conjoint analysis design and implementation for healthcare decision-making.

Appendix 1 of the research paper contains the details of the CA study. In the Appendix 1, Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the attributes and levels that were assessed throughout the investigation. Ten distinct scenarios, each with two alternatives (Option A and Option B), comprised the study. Option A possessed constant attributes, whereas Option B varied across scenarios. This setup resulted in 10 pairwise choices used in the CA questions.

Table 2 in Appendix 1 presents an example of one such pairwise choice.

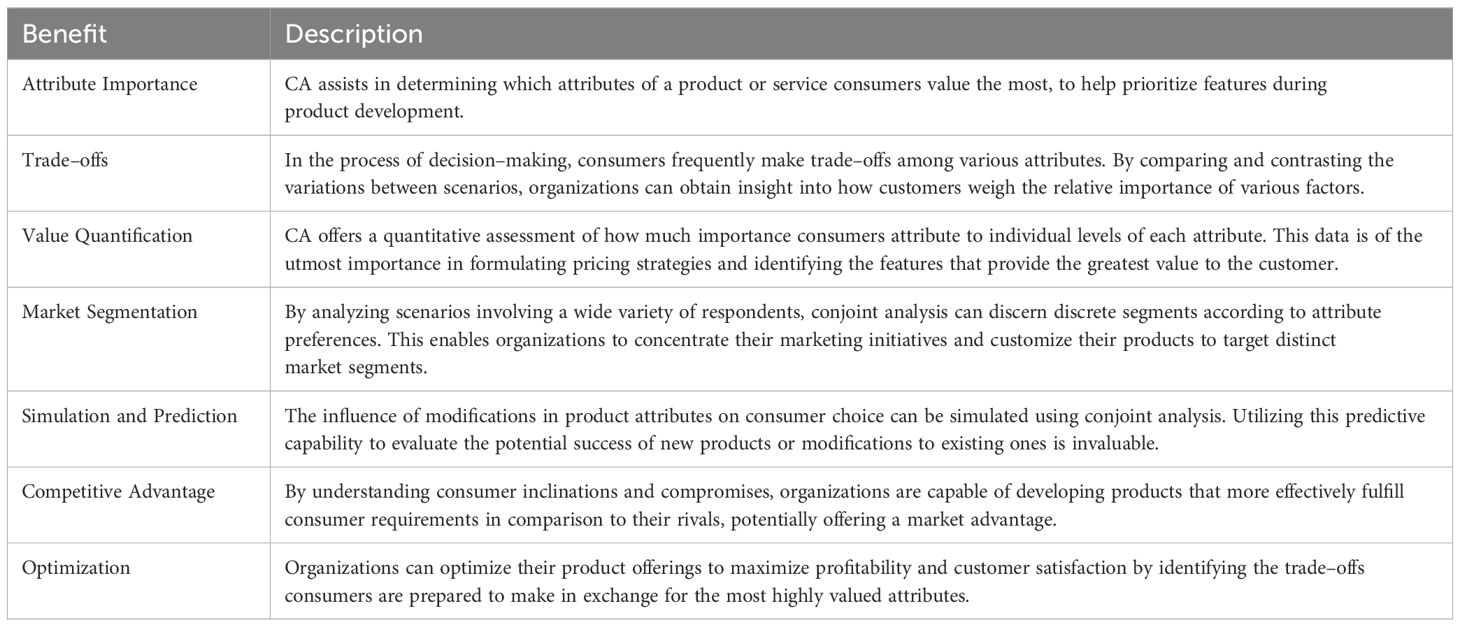

CA is important for several reasons as described in Table 2:

Table 2. Key benefits and applications of conjoint analysis in evaluating healthcare preferences.

Using CA to examine the distinctions between scenarios yields comprehensive insights into the decision–making processes of consumers, helping businesses align their products and services with consumer preferences and improving market fit.

Scenarios are presented in Table 3 in Appendix 1 – according to the distinction between options B and A.

Exploratory factor analysis of the attributes relevant to the decision to cryopreserve oocyte: Risk of infertility, Chances of success of the oocyte cryopreservation process, Chance of initiating a pregnancy from frozen oocyte, Option of oocyte cryopreservation for chosen period of time (Years), Initial registration fee to fertility laboratory and cryopreservation (One–time payment), Annual fee for cryopreservation and must be paid every year (storage) was carried out using Principal Component Analysis, Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. This analysis yielded two factors:

1. Factor_Risk=Mean (Risk of infertility, Chances of success of the oocyte cryopreservation process, Chance of initiating a pregnancy from frozen oocyte, Option of oocyte cryopreservation for chosen period of time (years).

2. Factor_Price=Mean (Initial registration fee to fertility laboratory and cryopreservation (one–time payment), Annual fee for cryopreservation and must be paid every year (storage)

The regression function estimated is denoted by Equation 1 and Equation 2.

ΔV=β0+β1 Risk of infertiliti+β2 Chances of success of the oocyte cryopreservation processi+β3 Chance of initiating a pregnancy from frozen oocytei+β4 Option of oocyte cryopreservation for chosen period of timei+β5 Initial registration fee to fertility laboratory and cryopreservationi+β6 Annual fee for cryopreservation and must be paid every yeari+ϵ(1)CA was estimated in accordance with the function of the form:

ΔV=β0+

留言 (0)