Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel coronavirus that emerged in late 2019 and caused a global pandemic (1). SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the Betacoronavirus genus and an RNA virus with a single-stranded genome (2). Its morphological structure comprises four major proteins, namely, nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M), envelope (E), and distinctive spike (S) proteins (3). The S protein, which gives the virus its characteristic appearance, plays a vital role in its interaction with the host cell (3). The S protein comprises two subunits, S1 and S2. The S1 subunit houses the receptor binding domain (RBD), which binds specifically to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor on the surface of host cells (4). Upon binding, the S2 subunit facilitates membrane fusion between the viral and host cell membranes, which enables viral entry and replication within the cell. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 exploits the ACE2 receptor as its primary gateway for infection (3, 4). This virus belongs to the coronavirus family, causes respiratory symptoms, and is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets (5).

1.2 Discovery of exosomes and milestones in its researchIn 1985, R M. Johnstone’s research team studied sheep reticulocyte vesicle secretion under an electron microscope and observed certain structures in the supernatant of sheep red blood cells cultured in vitro (6). Subsequently, in 1989, they were duly designated as exosomes (7). In 1996, a study by G Raposo et al. revealed that immune cells resembling B lymphocytes possess the capability to secrete antigen-presenting exosomes (8). Subsequently, in 2007, H Valadi et al. discovered that exosomes contain mRNA and microRNA, which are transferred to and translated into recipient cells (9). In recognition of their groundbreaking research on membrane vesicle transport, three American scientists, namely, Thomas Sudhof, James Rothman, and Randy Schekman were honored with the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 2013 (10). Since then, exosomes have gradually gained attention and become a hotspot in biomedical research. Exosomes have now been reported to play a role in diverse processes such as immune response, viral pathogenicity, pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, central nervous system-related diseases, and cancer progression (11).

1.3 Characteristics of exosomesExtracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny membrane-bound particles released into the extracellular space when the plasma membrane fuses with multivesicular bodies (MVBs) formed via endocytosis. This process occurs under both physiological and pathological conditions. These vesicles are categorized into three distinct classes based on their size: apoptotic bodies (>1000 nm), microvesicles (100–1000 nm), and exosomes (30–100 nm) (11). These vesicles can travel throughout the body via various body fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva (12). Their diverse cargo enables exosomes to facilitate intercellular communication and modulate several cellular functions (11). Exosomes, which originate from different cell types, encapsulate a wide array of cellular components, including DNA, RNA, lipids, metabolites, cytoplasmic proteins, and cell surface proteins. These cell-derived vesicles play a pertinent role in diversified physiological conditions, such as cancer, inflammation, and infection (13).

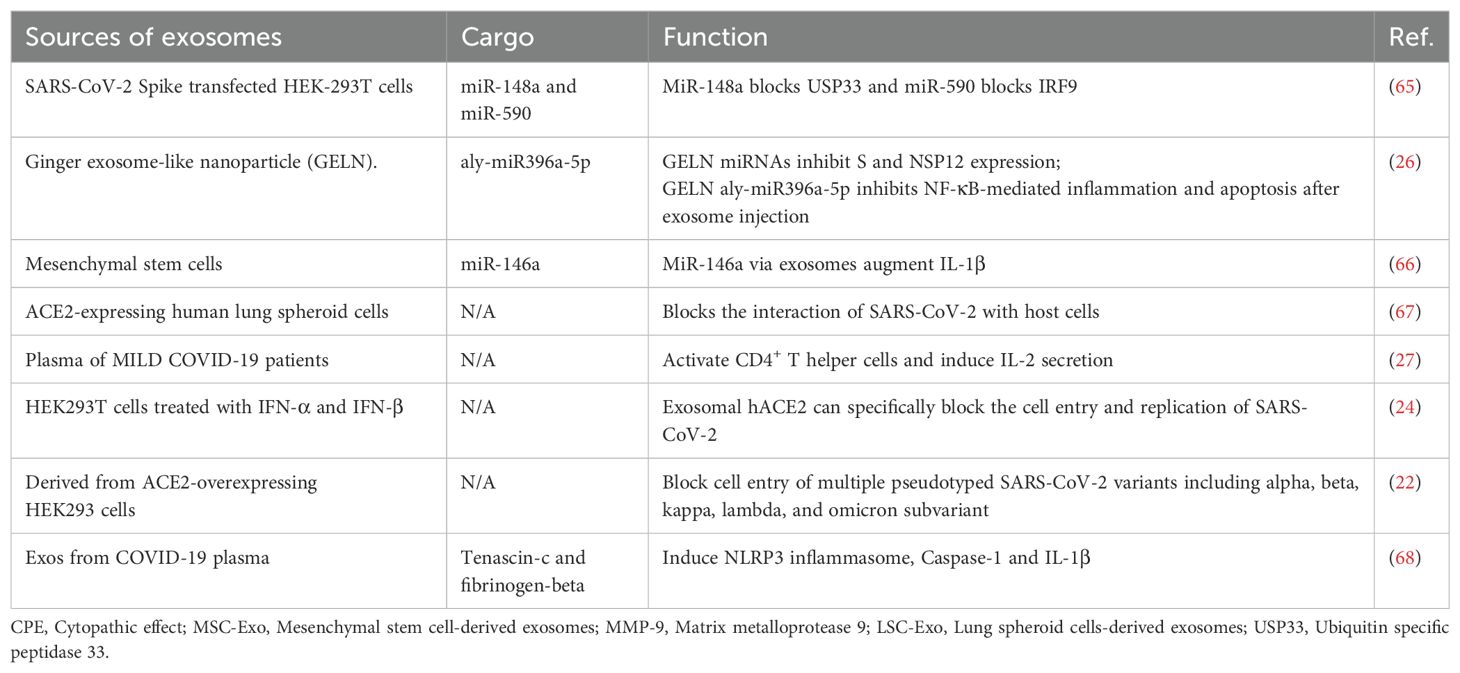

2 The role of exosomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection2.1 Emerging roles of exosomes during SARS-CoV-2 infectionIn recent years, exosomes have garnered widespread scientific attention as key mediators of intercellular communication. Exosome biogenesis shares similarities with virus biogenesis, and the cargo carried by these vesicles can considerably influence virus propagation, dissemination, and infection dynamics (13–15). Emerging studies have observed that exosomes may play critical roles in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Infected host cells release exosomes that contain viral RNA, proteins, and other bioactive molecules, which potentially facilitate viral transmission and modulate host immune responses (15). Conversely, exosomes exert complex effects on SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and either exacerbate or suppress disease progression. In addition, exosomes hold promise as noninvasive diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic delivery vehicles loaded with biomolecules or drugs (13, 16). The different types of exosomes and their respective functions are presented in Table 1. Comprehending the pivotal role of exosomes in viral infections and applying this knowledge to diagnostic and therapeutic strategies may provide beneficial insights into patient prognosis, disease prevention, and the development of novel therapeutic approaches.

Table 1. Different kinds of exosomes and their functions.

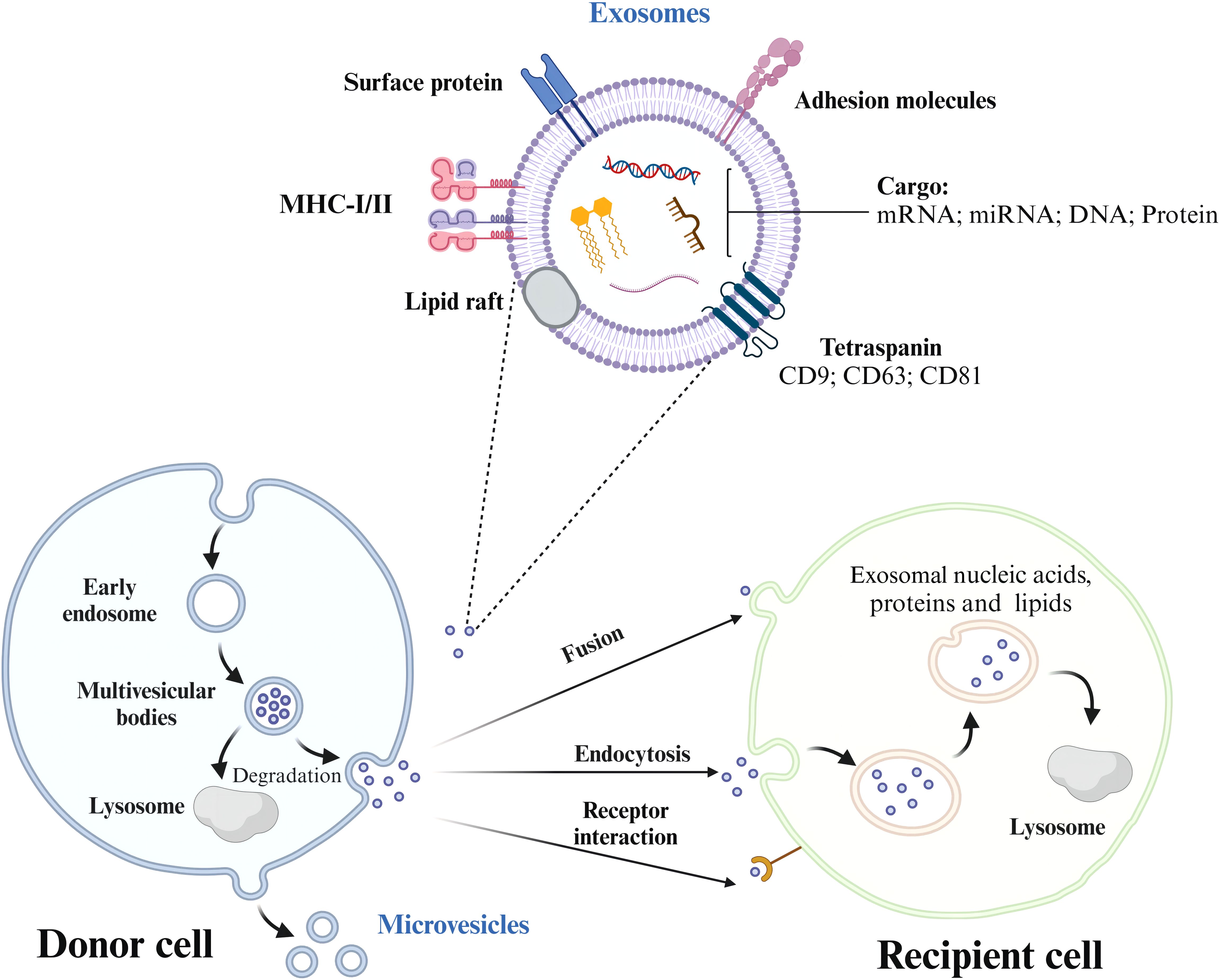

2.2 Signaling cascades of exosomes2.2.1 Fusion and formation stageThe biogenesis of exosomes begins with the endocytosis of molecular cargo. Early endosomes are the earliest vesicles formed upon internalization and mark the initial stage of the endosomal trafficking pathway. These early endosomes play a central role in sorting and determining the fate of the endocytosed cargo (17, 18). As these endosomes mature, changes occur in their membrane composition. Over time, the endosomal membrane invaginates and forms smaller vesicles called intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). Multivesicular bodies (MVBs) are structures that contain multiple ILVs enclosed by a membrane. The contents of ILVs are degraded when the MVBs fuse with lysosomes. Alternatively, the fusion of MVBs with the cell’s plasma membrane results in the secretion of ILVs into the extracellular environment, where they are transformed into exosomes (18).

2.3 Trafficking process and releaseThe cargo has three potential routes from the early endosome. The cargo meant for recycling moves to the peripheral tubular regions of the endosomes and subsequently dissociates and merges either with the Golgi network or the plasma membrane within the recycling endosome. However, the cargo not destined for recycling accumulates in the central vacuolar regions of the early endosome. This accumulated cargo initiates endosomal maturation and leads to the formation of the late endosome. Late endosomes have two possible outcomes: fusion with lysosomes for degradation or fusion with the plasma membrane for exosome release (19). When the MVBs are appropriately stimulated, they migrate from the perinuclear cytoplasm to the plasma membrane and reside in a quiescent state within cells. The MVBs are then fused via exocytosis (Figure 1, Table 2). The sites of fusion vary depending on the cell type and range from the entire plasma membrane to localized areas. Exocytosis is followed by MVB secretion, which releases the exosomes into the extracellular fluid.

Figure 1. The process of exosome formation, release, and uptake by recipient cells. Exosomes are formed from early endosomes, which ingest molecular cargo via endocytosis. As these early endosomes mature, they develop into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) that contain intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). Depending on their fate, MVBs either fuse with lysosomes to degrade their cargo or with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space. Exosome trafficking involves the migration of MVBs to the plasma membrane, followed by exocytosis, enabling bioactive compounds to interact with receptors on the target cell.

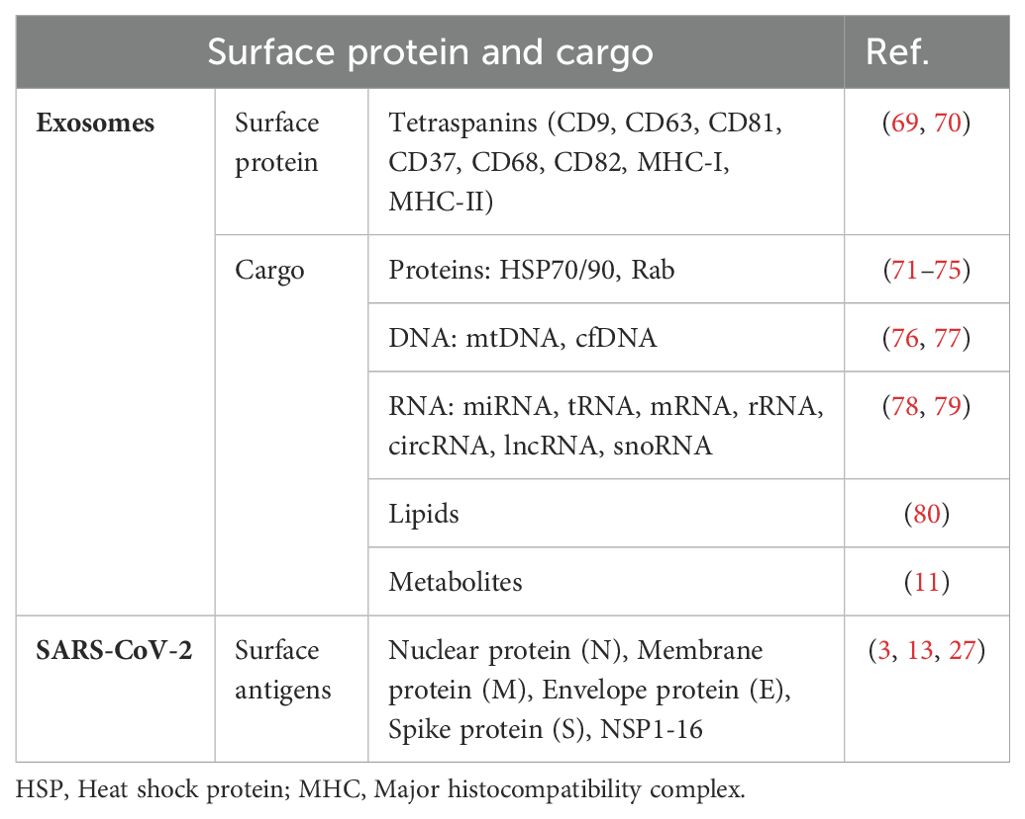

Table 2. The main exosome surface protein and cargo, SARS-CoV-2 surface antigen.

2.4 Uptake of exosomes by the recipient cellsAfter the vesicles are released, their membranes undergo predominant activities. Initially, the vesicles face environmental alterations during their transition from the cell’s cytosol to the extracellular fluid. Subsequently, the vesicles interact with the plasma and endocytic membranes in the target cells. Ultimately, the ensuing merging of EVs with cellular membranes marks the end of the extracellular EV route. When liberated from progenitor cells, some vesicles remain intact for a brief period before undergoing membrane disintegration. These vesicles release bioactive substances such as interleukin-1β and various growth factors (TGFβ, FGF, VEGF, etc.), which allows them to bind directly to receptors on neighboring cells and initiate specific reactions. Nonetheless, most EVs resist membrane degradation and remain in the extracellular fluid for extended periods. Surface enzymes and various molecules facilitate pre-binding interactions with adjacent cells, which contribute to the breakdown of extracellular structures. Furthermore, EVs often accumulate near intercellular junctions in the extracellular areas and traverse the intercellular space. As a result of these movements, EVs exit the original fluid and migrate to nearby tissue regions (20), potentially entering larger fluid bodies, such as the blood serum, lymph, and cerebrospinal fluid. Once the target cells are identified, EVs (often studied using optical tweezers) establish connections with their surface (21). Finally, the vesicles merge with the plasma or endocytic membrane and release the luminal contents into the cytosol.

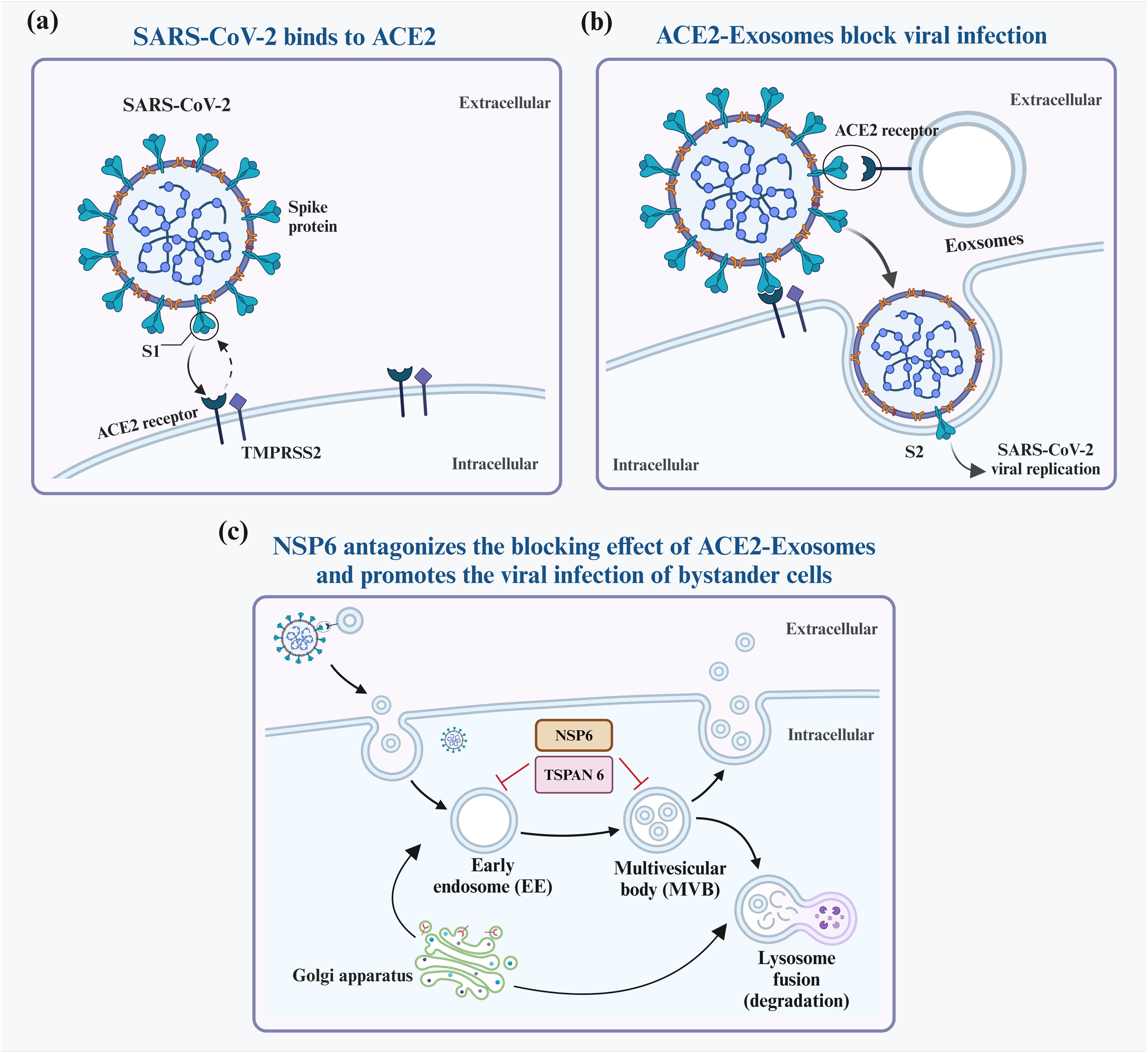

3 Exosomes regulate viral infection via various molecular mechanisms3.1 Exosomes containing ACE2 proteins bind competitively to viral S proteinElevated levels of EVs expressing ACE2 (evACE2) in the blood of patients with COVID-19 are marked by distinct exosome markers (22). These vesicles can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by competitively binding to ACE2. Lv et al. reported that SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 6 (NSP6) could suppress the antiviral action of ACE2-exos and promote viral invasion. Furthermore, tetraspanin-6 negatively regulates exosome production (Figure 2) (22, 23). In human ACE2 (hACE2) mice infected with SARS-CoV-2, the presence of evACE2 has been linked to reduced mortality rates (21). evACE2 inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection by blocking the binding of the viral S protein with its cellular receptor ACE2 in host cells. Compared with vesicle-free recombinant hACE2, evACE2 demonstrates a 135-fold higher potency in blocking the binding of the viral S protein RBD and a 60–80-fold higher efficacy in preventing infections by both pseudotyped and authentic SARS-CoV-2 (21). These findings suggest a promising therapeutic avenue to manage COVID-19. Furthermore, treatment with IFN-α/β has been noted to augment the expression of hACE2. This exosomal form specifically inhibits viral entry into target cells, thereby suppressing SARS-CoV-2 replication both in vitro and ex vivo (24). An intranasal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine utilizing EVs derived from Salmonella typhimurium has been shown to elicit neutralizing antibodies against both wild-type and Delta variant strains (25). Moreover, the novel SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate based on bacterial EVs has been documented to alleviate lung lesions and improve weight loss (25). Compared with animals in the control group, the vaccinated animals experienced significantly less body mass loss after the viral challenge and, in some instances, even showed mass gains (25). In addition, vaccinated hamsters displayed fewer focal patches of inflammation, alveolar collapse, and hemorrhagic areas of the lung. These observations emphasize the significance of EVs in developing SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (25).

Figure 2. Interaction between exosomes and SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 infects host cells predominantly by attaching to ACE2 receptors on their surfaces (A). To block infection, ACE2-containing exosomes (ACE2-Exosomes) can be activated and bind to free virions, preventing susceptible bystander cells from becoming infected (B). However, SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 suppresses the formation of ACE2-Exosomes, thereby enabling viral infection of neighboring cells (C).

3.2 Exosomes contain proteins that regulate antiviral immune responsesExosomes originate from various cells that contain distinct proteins. For example, exosomes released by virus-infected cells carry viral protein particles that facilitate viral spread. A novel biological activity of SARS-CoV-2, i.e., activation of macrophages via the NF-κB-mediated pathway, was identified (26). Lung epithelial cell exosomes deliver NSP12 to macrophages, triggering their activation via NF-κB. Subsequently, the activated macrophages release inflammatory cytokines that lead to lung inflammation (26). In addition, exosomes carrying NSP13 have been observed to synergistically enhance NF-κB activation along with NSP12 (26). Metabolites released from macrophages activated by exosomes NSP12 and NSP13 have been shown to induce apoptosis in lung epithelial cells (27). These findings highlight the role of exosomes in delivering viral proteins and modulating immune responses in lung epithelial cells.

3.3 Mechanism of exosome delivery of noncoding RNAs in viral infectionNoncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) play crucial roles in regulating cellular immunity (28). Several types of ncRNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), influence cell development, proliferation, and metabolism via diverse mechanisms (29, 30). Valadi et al. first reported that exosomes from murine and human mast cell lines (MC/9 and HMC-1) contain miRNAs and mRNAs that can be transferred to other cells (9). Studies have observed that various ncRNAs can be encapsulated and transported by exosomes (31, 32).

Moreover, exosomal mRNAs can be transported to recipient cells, where they are translated and contribute to the recipient cell’s protein expression. For instance, when internalized by TCA8113 cells, full-length ECRG4 mRNA occurring in serum exosomes inhibits receptor cell inflammation, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation (33). The presence of miRNAs within exosomes implies that they can be directly transported to specific cells and functionally influence mRNA targets. In the context of disease mechanisms, exosomes derived from vascular smooth muscle cells enable the transfer of miR-155 induced by KLF5 from smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells. This transfer promotes endothelial injury and atherosclerosis progression by suppressing the expression of zonula occludens-1 (34). In addition, specific proteins in lncRNA vectors regulate the sorting of lncRNAs into exosomes, and lncRNA–RNA–binding protein complexes selectively collect and sort specific miRNAs (35). Similarly, circRNAs, like lncRNAs, can be transported by exosomes between donor and recipient cells. MCPyV circALTOs are enriched in exosomes derived from VP-MCC lines and circALTO-transfected 293T cells. Also, purified exosomes can mediate ALTO expression and transcriptional activation in MCPyV-negative cells (36).

3.4 Mechanisms involved in exosomes transporting other cargo to orchestrate immune responsesExosomes possess unique abilities to target specific tissues or cells and traverse biological barriers, including the blood–brain barrier, which makes them promising candidates for targeted drug delivery. These vesicles can effectively transport a wide array of therapeutic substances, which range from genetic drugs to traditional Chinese and Western medicines (37, 38). Owing to these inherent advantages, exosomes are versatile vehicles for precise and efficient drug delivery. For instance, paclitaxel (PTX), the drug used extensively in cancer treatment, faces challenges such as high hydrophobicity, dose-dependent toxicity, and side effects (39, 40). In a recent study by Wang et al., exosomes derived from classically activated M1 macrophages were used as carriers to mitigate PTX toxicity and improve its bioavailability. PTX was successfully delivered to tumor tissues in mice, inducing a proinflammatory response via NF-κB pathway activation, thereby augmenting the therapeutic efficacy of the drug (41). Catalase (CAT), a potent antioxidant used to treat neurodegenerative diseases by inhibiting inflammation and protecting dopaminergic neurons, is limited by the impermeability of the blood–brain barrier to most therapeutic agents (42, 43). Haney et al. found that coating the enzyme with exosomes effectively reduces oxidative stress and enhances neuronal survival in both in vivo and in vitro models. Loading CAT onto exosomes preserves its biological activity, extends its blood circulation time, decreases its immunogenicity, and overcomes issues such as rapid degradation, considerably improving the therapeutic efficacy (44).

4 Clinical findings and correlation between exosomes and disease severity4.1 Association between exosomes and disease severitySerum-derived exosomes in patients with COVID-19 have been linked to disease severity (27). Elisa et al. analyzed plasma samples from 20 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and observed that those with mild symptoms had a higher number of circulating SARS-CoV-2-S exosomes than those with severe symptoms (27). In another study, Song et al. reported elevated levels of gangliosides and sphingomyelin in the serum of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, along with the absence of diacylglycerol, which is a distinct lipid pattern specific to exosomes (45). In their study, Kwon et al. showed that pulmonary epithelial A549 cells transfected with nonstructural and structural genes of SARS-CoV-2 released viral RNA-rich exosomes (46). Hence, analyzing SARS-CoV-2-related markers within exosomes isolated from the patient’s body fluids can aid in evaluating the viral replication status and immune response, facilitating predictions of disease severity and prognosis (47–49). Several studies have observed that infection with SARS-CoV-2 results in a general increase in the expressions of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) and immune response mediators (50, 51). Endogenous retrovirus transcripts and proteins can be exported in EVs, which makes HERVs a contributing element in COVID-19 and early genomic biomarkers to predict COVID-19 severity and outcome (52, 53). Thus, SARS-CoV-2 exosomes are vital indicators of the functional status of the patient’s immune cells and exhibit distinct characteristics in those with mild symptoms (27). This unique feature provides a theoretical foundation for further studies on alternative exosomal approaches for preventive or therapeutic strategies against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

4.2 The application of exosome-based vaccines in clinical diseasesExosomes have emerged as a promising therapeutic option owing to their advantageous characteristics, such as small size, non-toxicity, low immunogenicity, high stability, and ease of storage (54). In the field of vaccine development, exosomes are being actively investigated as a platform to construct safe and efficacious vaccine vectors. For example, exosomes loaded with the SARS S protein can effectively induce neutralizing antibody (55). A chimeric protein (SGTM) was engineered in the study by replacing the transmembrane domain of SARS-S with the G protein of the vesicular stomatitis virus, which resulted in a vaccine against the SARS coronavirus (55). This innovative exosome-based vaccine strategy can overcome the challenges linked to conventional vaccines, such as storage and stability issues. Exosomes can protect their cargo from degradation and may evade neutralization by antibodies, which enhances the efficacy and durability of the vaccine (56, 57). Moreover, engineered EVs expressing the ACE2 receptor can act as decoys to prevent the SARS-CoV-2 S protein from infecting healthy cells (58). A study showed that EVs expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 decreased the infection rate of healthy Caco-2 cells by 50% (59). Another study proposed the use of evACE2 derived from mesenchymal stem cells to bind the S protein competitively. This binding protected the cells from damage and maintained ACE2 surface expression. Acute lung injury and endothelial dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection were thus prevented (60).

5 ConclusionExosomes are crucial vectors for virus transmission and influence viral replication in two ways. On the one hand, they promote virus replication, transmission, and infection and downregulate antiviral immunity (14, 61, 62). On the other hand, they limit viral infection and potentiate antiviral immunity. For instance, HIV packages viral proteins and RNA into vesicles during cellular infection. These vesicles are later released into the extracellular space, which aids in viral spread to noninfected cells (63). Nevertheless, this phenomenon has not yet been demonstrated in SARS-CoV-2 (64).

EVs expressing ACE2 neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by competitively binding to ACE2 and specifically blocking viral entry into target cells, thereby inhibiting viral replication in vitro and ex vivo. The studies conducted so far have confirmed that exosomes are a double-edged sword in viral infection. Future studies should aim to elucidate these dual roles and examine how exosome-mediated interactions can be harnessed to devise novel therapeutic strategies against COVID-19. Understanding the specific mechanisms by which exosomes influence viral behavior and immune responses may provide beneficial insights for designing effective interventions. Moreover, investigating the potential of exosome-based therapies could open new avenues to enhance antiviral immunity, paving the way for innovative therapeutic strategies that leverage the natural properties of exosomes in combating viral infections.

In summary, the nuanced roles of exosomes in viral transmission and immune modulation present challenges as well as opportunities for future research. The continued exploration in this field may not only broaden our understanding of viral pathogenesis but also contribute to the development of more effective antiviral therapies.

6 OutlookDespite the promising potential of exosomes in treating COVID-19, research in this area is fraught with several challenges. Exosome purity and safety should be ensured, particularly for clinical applications, and protocols for mass production, transport, storage, management, and monitoring of exosomes should be standardized. A lack of these measures may hinder the transition from laboratory research to clinical implementation. Moreover, current research has not clarified the mechanisms by which exosomes operate in the SARS-CoV-2 infection process. Several issues warrant further investigation, including how exosomes specifically influence viral transmission and immune responses and the ways to optimize their application for enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Exploring the important roles and unique characteristics of exosomes in the human body could, therefore, improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy for COVID-19, bringing us one step closer to clinical implementation in the future. A wealth of basic research in exosome delivery systems suggests that they can help overcome the challenges and dilemmas associated with the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. By leveraging these insights, we can develop innovative therapeutic strategies that harness the potential of exosomes in combating COVID-19.

Author contributionsLL: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. ZY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Key Research and Development Plan of the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department (Number: 2022YFS0392), the Key Research and Development Plan of the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department (24ZDYF0804), and Science and Technology Research Special Subjects of Sichuan Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023MS252).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Sharma A, Tiwari S, Deb MK, Marty JL. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (sars-cov-2): A global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. (2020) 56:106054. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106054

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (London England). (2020) 395:565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Pan BT, Teng K, Wu C, Adam M, Johnstone RM. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. (1985) 101:942–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.942

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, Liejendekker R, Harding CV, Melief CJ, et al. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med. (1996) 183:1161–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1161

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mrnas and micrornas is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Wickner WT. Profile of thomas sudhof, james rothman, and randy schekman, 2013 nobel laureates in physiology or medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2013) 110:18349–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319309110

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Gorgzadeh A, Nazari A, Ali Ehsan Ismaeel A, Safarzadeh D, Hassan JAK, Mohammadzadehsaliani S, et al. A state-of-the-art review of the recent advances in exosome isolation and detection methods in viral infection. Virol J. (2024) 21:34. doi: 10.1186/s12985-024-02301-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Hassanpour M, Rezaie J, Nouri M, Panahi Y. The role of extracellular vesicles in covid-19 virus infection. Infection Genet Evolution: J Mol Epidemiol Evolutionary Genet Infect Dis. (2020) 85:104422. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104422

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Wiesner C, El Azzouzi K, Linder S. A specific subset of rabgtpases controls cell surface exposure of mt1-mmp, extracellular matrix degradation and three-dimensional invasion of macrophages. J Cell Sci. (2013) 126:2820–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.122358

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. El-Shennawy L, Hoffmann AD, Dashzeveg NK, McAndrews KM, Mehl PJ, Cornish D, et al. Circulating ace2-expressing extracellular vesicles block broad strains of sars-cov-2. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:405. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27893-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Lv X, Chen R, Liang T, Peng H, Fang Q, Xiao S, et al. Nsp6 inhibits the production of ace2-containing exosomes to promote sars-cov-2 infectivity. mBio. (2024) 15:e0335823. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03358-23

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Ghossoub R, Chéry M, Audebert S, Leblanc R, Egea-Jimenez AL, Lembo F, et al. Tetraspanin-6 negatively regulates exosome production. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2020) 117:5913–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922447117

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Zhang J, Huang F, Xia B, Yuan Y, Yu F, Wang G, et al. The interferon-stimulated exosomal hace2 potently inhibits sars-cov-2 replication through competitively blocking the virus entry. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2021) 6:189. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00604-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Jiang L, Driedonks TAP, Jong WSP, Dhakal S, Bart van den Berg van Saparoea H, Sitaras I, et al. A bacterial extracellular vesicle-based intranasal vaccine against sars-cov-2 protects against disease and elicits neutralizing antibodies to wild-type and delta variants. J Extracellular Vesicles. (2022) 11:e12192. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12192

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Teng Y, Xu F, Zhang X, Mu J, Sayed M, Hu X, et al. Plant-derived exosomal micrornas inhibit lung inflammation induced by exosomes sars-cov-2 nsp12. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Ther. (2021) 29:2424–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.05.005

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Pesce E, Manfrini N, Cordiglieri C, Santi S, Bandera A, Gobbini A, et al. Exosomes recovered from the plasma of covid-19 patients expose sars-cov-2 spike-derived fragments and contribute to the adaptive immune response. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:785941. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.785941

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Xu Z, Chen Y, Ma L, Chen Y, Liu J, Guo Y, et al. Role of exosomal non-coding rnas from tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Ther. (2022) 30:3133–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.046

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Lai X, Zhong J, Zhang B, Zhu T, Liao R. Exosomal non-coding rnas: Novel regulators of macrophage-linked intercellular communication in lung cancer and inflammatory lung diseases. Biomolecules. (2023) 13(3):536. doi: 10.3390/biom13030536

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Zhou X, Liu Q, Wang X, Yao X, Zhang B, Wu J, et al. Exosomal ncrnas facilitate interactive ‘dialogue’ between tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Lett. (2023) 552:215975. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215975

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Mao L, Li X, Gong S, Yuan H, Jiang Y, Huang W, et al. Serum exosomes contain ecrg4 mrna that suppresses tumor growth via inhibition of genes involved in inflammation, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis. Cancer Gene Ther. (2018) 25:248–59. doi: 10.1038/s41417-018-0032-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Zheng B, Yin WN, Suzuki T, Zhang XH, Zhang Y, Song LL, et al. Exosome-mediated mir-155 transfer from smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells induces endothelial injury and promotes atherosclerosis. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Ther. (2017) 25:1279–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.031

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Ahadi A, Brennan S, Kennedy PJ, Hutvagner G, Tran N. Long non-coding rnas harboring mirna seed regions are enriched in prostate cancer exosomes. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:24922. doi: 10.1038/srep24922

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Yang R, Lee EE, Kim J, Choi JH, Kolitz E, Chen Y, et al. Characterization of alto-encoding circular rnas expressed by merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa polyomavirus. PloS Pathog. (2021) 17:e1009582. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009582

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Tatischeff I, Alfsen AJ. Nanobiotechnology. A new biological strategy for drug delivery: Eucaryotic cell-derived nanovesicles. Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology. (2011) 02:494–9. doi: 10.4236/jbnb.2011.225060

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Fu B, Wang N, Tan HY, Li S, Cheung F, Feng Y. Multi-component herbal products in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-associated toxicity and side effects: A review on experimental and clinical evidences. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:1394. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01394

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Oun R, Moussa YE, Wheate NJ. Correction: The side effects of platinum-based chemotherapy drugs: A review for chemists. Dalton Trans (Cambridge England: 2003). (2018) 47:7848. doi: 10.1039/C8DT90088D

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Wang P, Wang H, Huang Q, Peng C, Yao L, Chen H, et al. Exosomes from m1-polarized macrophages enhance paclitaxel antitumor activity by activating macrophages-mediated inflammation. Theranostics. (2019) 9:1714–27. doi: 10.7150/thno.30716

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Zhang Y, Bi J, Huang J, Tang Y, Du S, Li P, et al. Exosome: A review of its classification, isolation techniques, storage, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications. Int J Nanomed. (2020) 15:6917–34. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S264498

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Agrawal M, Ajazuddin, Tripathi DK, Saraf S, Saraf S, Antimisiaris SG, et al. Recent advancements in liposomes targeting strategies to cross blood-brain barrier (bbb) for the treatment of alzheimer’s disease. J Controlled Release: Off J Controlled Release Soc. (2017) 260:61–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.05.019

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Zhao Y, Gupta R, Plotnikova EG, He Z, et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for parkinson’s disease therapy. J Controlled Release: Off J Controlled Release Soc. (2015) 207:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Song JW, Lam SM, Fan X, Cao WJ, Wang SY, Tian H, et al. Omics-driven systems interrogation of metabolic dysregulation in covid-19 pathogenesis. Cell Metab. (2020) 32:188–202.e185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.016

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Hashemian SMR, Pourhanifeh MH, Hamblin MR, Hamblin MR, Shahrzad MK, Mirzaei H. Rdrp inhibitors and covid-19: Is molnupiravir a good option? Biomed Pharmacother Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 146:112517. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112517

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Ashwlayan VD, Antlash C, Imran M, Asdaq SMB, Alshammari MK, Alomani M, et al. Insight into the biological impact of covid-19 and its vaccines on huma

留言 (0)