Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neurological disorder caused by acute liver failure, chronic liver disease (Haussinger et al., 2022; Wijdicks, 2016), and liver-independent portosystemic shunts (Hawkes et al., 2001; Vilstrup et al., 2014). The disorder manifests a spectrum of neuro-psychiatric symptoms ranging from subtle changes detectable only through specialized testing to severe cognitive and motor impairments, and in extreme cases, death (Rose et al., 2020; Vidal-Cevallos et al., 2022; Vilstrup et al., 2014). A prominent feature of HE is hyperammonemia, defined as abnormally high ammonia levels in the blood (Ong et al., 2003). Ammonia can cross the blood–brain interface (Jayakumar and Norenberg, 2018; Lockwood et al., 1979; Vidal-Cevallos et al., 2022) leading to cognitive and motor dysfunctions (Butz et al., 2010; Felipo, 2013; Garcia-Garcia et al., 2018), disorientation (Weissenborn, 1998), asterixis, which is characterized by an inability to sustain posture and involuntary movements (Zackria and John, 2023), and coma (Bessman and Bessman, 1955; Wijdicks, 2016).

Animal models (DeMorrow et al., 2021) have played a crucial role in elucidating the neurological consequences of increased ammonia levels in HE (Lima et al., 2019). Neuroinflammation is now recognized as a significant factor in both acute and chronic HE, as evidenced by research using various animal models, including the ammonium-containing diet model (Rodrigo et al., 2010), the bile duct ligation model (Claeys et al., 2022; Rodrigo et al., 2010), and models of acute liver failure (Jiang et al., 2009a; Jiang et al., 2009b; Zemtsova et al., 2011). Furthermore, changes in astrocytic structure, such as swelling (Jayakumar et al., 2009; Jayakumar et al., 2014b; Rama Rao et al., 2010), altered function (Drews et al., 2020; Zielinska et al., 2022), and senescence (Gorg et al., 2015), have been consistently observed in response to hyperammonemia (Ali and Nagalli, 2023).

Astrocytes, integral to neuronal communication (Adermark et al., 2022; Akther and Hirase, 2022; Dallerac et al., 2013; Farhy-Tselnicker et al., 2021; Santello et al., 2019), are believed to be involved in the synaptic modifications induced by ammonia (Jayakumar et al., 2014a; Rangroo Thrane et al., 2013). Several studies have identified ammonia-induced neuronal changes (Kelly and Church, 2005; Sancho-Alonso et al., 2022b), which have been linked to impaired astrocytic function in clearing glutamate and potassium (Rangroo Thrane et al., 2013). Astrocytes express glutamine synthetase, which converts ammonia and glutamate into glutamine, aiding in ammonia detoxification and glutamate clearance (Rose et al., 2013; Suarez et al., 2002). Additionally, astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) are critical for glutamate re-uptake at synapses and neuronal functionality (Limon et al., 2021; Todd and Hardingham, 2020). Dysfunctions in these astrocytic EAATs have been associated with HE pathology in animal models (Knecht et al., 1997; Rose, 2006), with high ammonia levels leading to cognitive impairments, fear memory deficits, and seizures (Balzano et al., 2020; Cabrera-Pastor et al., 2016; Llansola et al., 2015; Qvartskhava et al., 2015; Rangroo Thrane et al., 2013; Rodrigo et al., 2010). Despite these insights, the exact cellular mechanisms by which ammonia induces changes in synaptic activity and transmission are still not fully understood.

This study investigated the acute effects of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) on excitatory synaptic activity in 3-week-old entorhino-hippocampal tissue cultures of mice. These cultures maintain a cytoarchitecture and fiber organization that resemble in vivo conditions, allowing for the examination of neurons and glial cells without the need for interventions such as anesthesia, brain extraction, and slice preparation immediately before experimental assessment. We employed single-cell and paired whole-cell CA3-CA1 recordings to assess the acute effects of NH4Cl on synaptic transmission and passive membrane properties of CA1 neurons and astrocytes. Notably, the effects of NH4Cl on synaptic plasticity induction have been studied before at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses (c.f., Fan and Szerb, 1993). Our results revealed that short exposure to 5 mM NH4Cl significantly decreased spontaneous excitatory synaptic activity. This reduction in synaptic transmission coincided with astrocyte depolarization. Importantly, when we inhibited glutamine synthetase, the NH4Cl-induced suppression of excitatory transmission was counteracted.

Materials and methods Ethics statementMice were maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Every effort was made to minimize distress and pain of animals. All experimental procedures were performed according to German animal welfare legislation and approved by the appropriate animal welfare committee and the animal welfare officer of Freiburg University (AZ X-17/07 K).

AnimalsWild type C57BL/6J mice of either sex were used in this study.

Preparation of tissue culturesOrganotypic entorhino-hippocampal tissue cultures were prepared at postnatal day 4–5 from C57BL/6J mice of either sex as previously described (Del Turco and Deller, 2007). Briefly, mice were rapidly decapitated and their brains were quickly extracted and transferred to a Vibratome VT1200S (Leica) for 300 μm slicing. The tissue cultures were transferred for cultivation onto porous (0.4 μm pore size, hydrophilic PTFE) cell culture inserts with 30 mm diameter (Millipore, Cat# PICM0RG50). The culturing medium consisted of 50% (v/v) minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco, Cat# 21575–022), 25% (v/v) basal medium eagle (BME; Gibco, Cat# 41010–026), 25% (v/v) heat-inactivated normal horse serum (NHS; Gibco, Cat# 26050–088), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Gibco, Cat# 35050–038), 0.65% (w/v) glucose (Sigma, Cat# G8769), 25 mM HEPES buffer solution (Gibco, Cat# 15630–056), 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin with 100 U/mL penicillin (Sigma, Cat# P0781) and 0.15% (w/v) bicarbonate (Gibco, Cat# 25080–060). The pH of the culturing medium was adjusted to 7.30 and tissue cultures were incubated for at least 18 days at 35°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The culturing medium was replaced thrice a week.

PharmacologyOrganotypic entorhino-hippocampal tissue cultures (≥18 days in vitro) were acutely exposed to NH4Cl (5 mM; Sigma, Cat# A9434), NaCl (5 mM; Sigma, Cat# S7653), KCl (5 mM; Sigma, Cat# P5405) or sucrose (10 mM; Sigma, Cat# S7903). Methionine sulfoximine (MSO; 5 mM; Sigma, Cat# M5379) was used to inhibit glutamine synthetase.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings and paired recordingsWhole-cell patch-clamp recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons of tissue cultures were carried out at 35°C (1–3 cells per culture). For recordings of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) the bath solution (artificial cerebrospinal fluid, ACSF) contained 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose and was saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. For recording of intrinsic cellular properties in current-clamp mode, the basic bath solution contained also 10 μM D-APV, 10 μM NBQX (Tocris; Cat# 0373) and 10 μM BMI (Sigma, Cat# 14343) or 10 μM Gabazine (Sigma, Cat# S106). Patch pipettes for sEPSC recordings and for intrinsic cellular properties recordings contained 126 mM K-gluconate, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM KCl, 4 mM ATP-Mg, 0.3 mM GTP-Na2, 10 mM PO-Creatine, and 0.1% (w/v) biocytin (pH 7.25 with KOH, 290 mOsm with sucrose, all from Sigma). Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV for CA1 pyramidal neurons. A holding potential of −80 mV was used for astrocytes in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus.

Series resistance was monitored before and after each recording, and recordings were discarded if the series resistance reached ≥30 MΩ. In current-clamp mode, I–V curves were generated for CA1 neurons by injecting 1 s square pulse currents, starting at −100 pA and increasing in 10 pA steps up to +40 pA (sweep duration: 2 s). For astrocyte membrane properties, I–V curves were generated by injecting 1 s square pulse currents, starting at −500 pA and increasing in 100 pA steps until +500 pA (sweep duration: 2 s). Resting membrane potential was assessed from the baseline value of the I–V-curve. Input resistance was calculated for the injection of −100 pA (CA1 pyramidal neurons) and − 500 pA (astrocytes) currents, respectively, within a 200 ms time frame at the end of the current step.

For paired whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, action potentials were generated in the presynaptic CA3 pyramidal neuron by square current pulses (1 nA) elicited at 0.1 Hz while recording evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) from CA1 pyramidal neurons for 20 min. Wash-in of ACSF containing 5 mM NH4Cl started after 10 min of baseline recordings. Neurons were considered connected if >5% of action potentials evoked time-locked inward eEPSCs within 10 ms after action potential induction.

Post hoc identification of recorded neurons and astrocytesAfter recording the intrinsic cellular properties, tissue cultures were fixed in a solution of 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 4% (w/v) sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. After fixation the tissue cultures were washed with 0.1 PBS. Afterwards, the fixed tissue cultures were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking solution consisting of 10% (v/v) normal goat serum (NGS; Fisher Scientific, Cat# NC9270494) and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in 0.1 M PBS. Biocytin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# B4261) filled neurons and astrocytes were stained with Alexa-488 or Alexa-633 conjugated Streptavidin (1:1000 in 0.1 M PBS with 10% NGS and 0.1% Triton X-100; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# S32354 or S21375) overnight at 4°C while shaking. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 62248) or TO-PRO® (Invitrogen, Cat# T-3605) staining was used to visualize cytoarchitecture (1:2000; in 0.1 M PBS for 15 min). Slices were washed three times with 0.1 M PBS, transferred and mounted onto glass slides with anti-fading mounting medium (DAKO; Agilent, Cat# S3023) for visualization. Streptavidin-stained CA1 pyramidal neurons were visualized with a Leica TCS SP8 laser scanning microscope with 20× (NA 0.75; Leica), 40× (NA 1.30; Leica) and 63× (NA 1.40; Leica) oil-submersion objectives.

Experimental design and statistical analysisElectrophysiological recordings were obtained using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices), digitized with Axon Digidata 1550B (Molecular Devices), and analyzed using Clampfit 11 of the pClamp11 software package (Molecular Devices). sEPSC properties were analyzed using the automated template search tool for event detection. Only inward current responses were analyzed in the respective experiments. Clampfit 11 (Molecular Devices®) was used to analyze paired recordings and the passive membrane properties of CA1 pyramidal neurons and astrocytes. Statistical comparisons were carried out using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad software). For comparison of two groups Mann–Whitney test was used. In order to statistically compare three groups of paired measurements, Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was selected. For statistical evaluation of XY-plots, a two-way ANOVA test followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was performed. To compare the mean values of amplitude, failure rate, decay and risetime before and after perfusion of NH4Cl for paired recordings, the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used. In Figure 1E, one cell that had a baseline amplitude, which was higher than three times the standard deviation value compared to the mean was excluded from further analysis (3× SD criterion). In Figure 2B, two cells that had an extremely aberrant increase in their frequency during wash-out (~11- and ~44-fold, respectively) after perfusion with NaCl were excluded from further analysis. In Figure 5, three cells that showed an aberrant increase or decrease in their amplitudes or frequencies under normal non-treated conditions (ACSF-only), with values during the last minute, three times different compared to the values of baseline, were also excluded from further analysis.

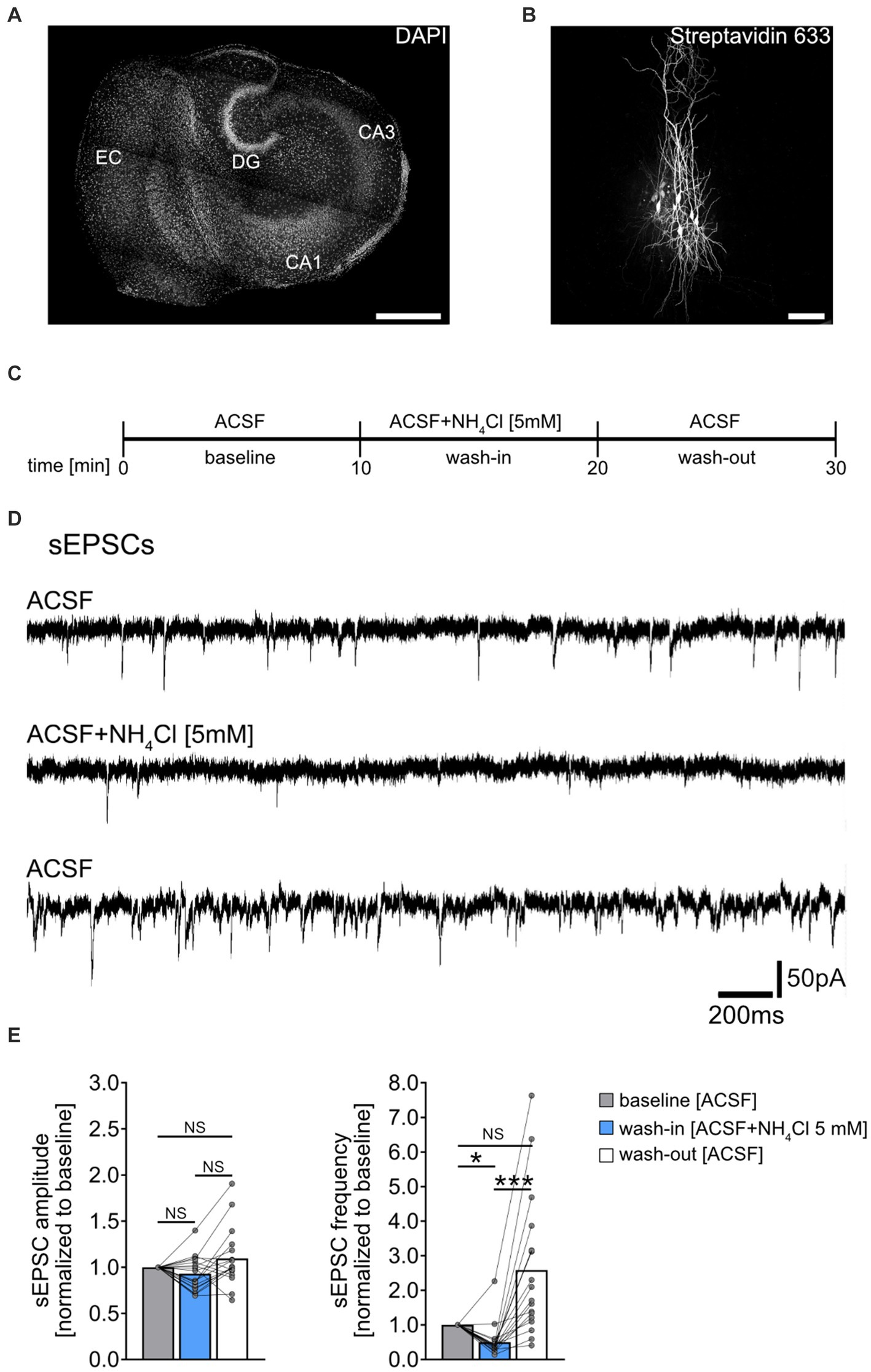

Figure 1. Effect of NH4Cl on spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons. (A) Overview of a mouse organotypic entorhino-hippocampal tissue culture stained with DAPI (EC, entorhinal cortex; DG, dentate gyrus; CA1, Cornu Ammonis 1; CA3, Cornu Ammonis 3). Scale bar, 400 μm. (B) Example of CA1 pyramidal neurons filled with biocytin during recording and post hoc-stained with Streptavidin 633. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. A 10-min baseline recording was followed by a 10-min wash-in of 5 mM NH4Cl, and subsequently, a 10-min wash-out with regular ACSF. (D,E) Sample traces and group data of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons before (10 min), during (10 min) and after (10 min) exposure to 5 mM NH4Cl (n = 18 cells from 11 cultures; 1 cell was excluded from the analysis based on the 3x SD criterion; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test; for comparison of the mean frequency pbaseline-wash-in = 0.014; pwash-in-wash-out < 0.001). Connected gray dots indicate data points from individual cells, values represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

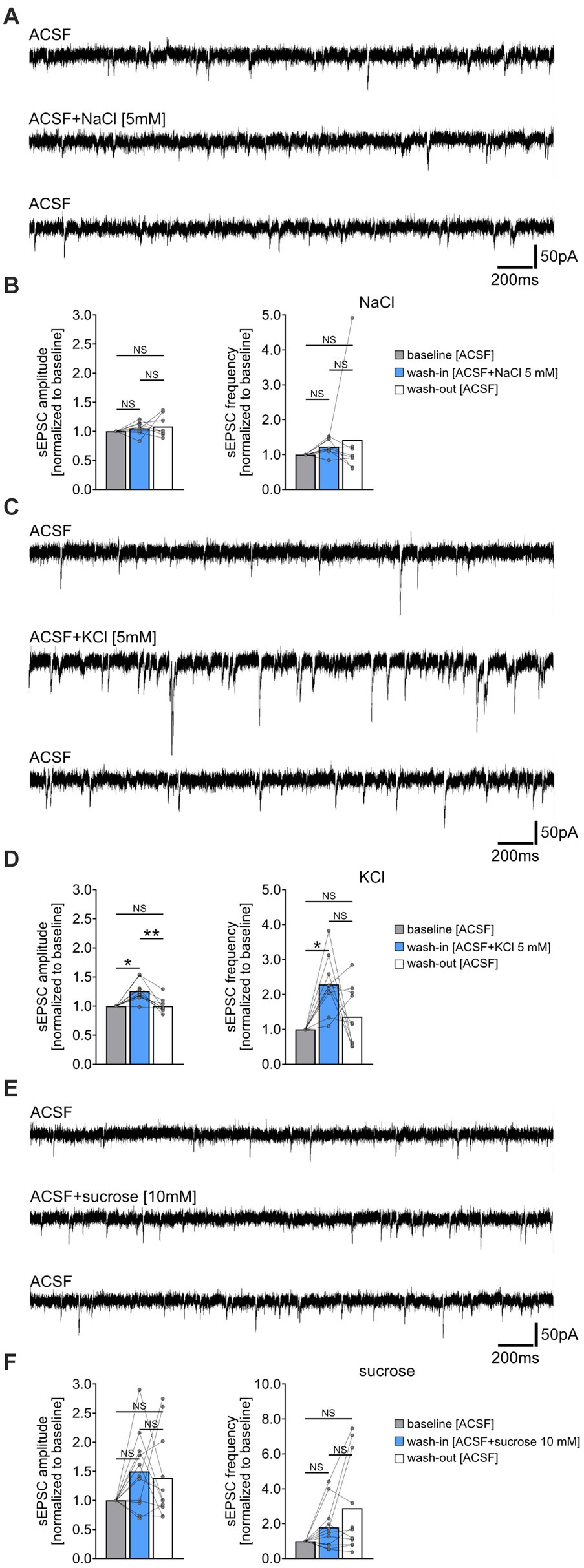

Figure 2. Increased extracellular chloride, potassium or osmolarity do not reduce the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSC). (A,B) Sample traces and group data of sEPSCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons of tissue cultures before (10 min), during (10 min), and after (10 min) exposure to 5 mM NaCl (n = 8 cells from 8 cultures; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test). (C,D) Sample traces and group data of sEPSCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons of tissue cultures before (10 min), during (10 min), and after (10 min) exposure to 5 mM KCl (n = 10 cells from 6 cultures; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test; for comparison of the mean amplitude: pbaseline-wash-in = 0.042; pwash-in-wash-out = 0.001. For comparison of the mean frequency pbaseline-wash-in = 0.011). (E,F) Sample traces and group data of sEPSCs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons of tissue cultures before (10 min), during (10 min), and after (10 min) exposure to 10 mM sucrose (n = 11 cells from 4 cultures; Friedman test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test). Connected gray dots indicate data points from individual cells, values represent mean ± SEM (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

Digital illustrationsFigures were prepared using the Affinity Designer (Serif Europe, Nottingham, United Kingdom) and the Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA, United States) graphics software. Image brightness and contrast were adjusted.

Results Acute exposure to NH4Cl attenuates sEPSC frequencySpontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded from individual CA1 pyramidal neurons of entorhino-hippocampal tissue cultures (≥18 days in vitro; Figures 1A,B), to assess acute effects of NH4Cl on excitatory synaptic activity. Baseline recordings were taken in ACSF for 10 min, followed by a 10-min exposure to 5 mM NH4Cl in ACSF, and a 10-min ACSF wash-out (Figures 1C,D). NH4Cl significantly reduced sEPSC frequencies without affecting mean sEPSC amplitude (Figure 1E). This effect was not permanent post-wash-out, with the vast majority of cells showing increased sEPSC frequencies afterwards (Figure 1E; baseline vs. post-wash-out; not significantly different statistically). The exact mechanism and reason for the increased sEPSC frequencies after wash-out are currently unknown.

Increased extracellular chloride, potassium or osmolarity do not reduce the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs)To determine if the NH4Cl-mediated reduction in sEPSC frequencies was due to increased extracellular chloride, potassium, or osmolarity, we performed the following control experiments. sEPSCs were recorded from another set of CA1 pyramidal neurons before and after washing-in 5 mM sodium chloride- (NaCl), 5 mM potassium chloride- (KCl) or 10 mM sucrose-containing ACSF (Figure 2). Prior to these experiments, we verified the pH and osmolarity of the solutions, noting an expected increase in osmolarity but not pH changes compared to ACSF alone (Supplementary Figure S1). Acute, i.e., 10 min exposure to 5 mM NaCl containing ACSF did not significantly affect sEPSC amplitudes and frequencies (Figures 2A,B). However, exposure to 5 mM KCl in ACSF led to a reversible enhancement in synaptic activity, marked by increased sEPSC amplitudes and frequencies (Figures 2C,D). The addition of 10 mM sucrose had no significant effect on sEPSC parameters (Figures 2E,F). Notably, we observed an increase in sEPSC frequencies in some cells after washout of NaCl, KCl, and sucrose, suggesting that this effect may not be specific to NH4Cl (c.f., Figure 1E). We conclude that the attenuation of sEPSC frequencies by NH4Cl is mediated by NH4+ cations, rather than by changes in extracellular chloride, potassium or osmolarity.

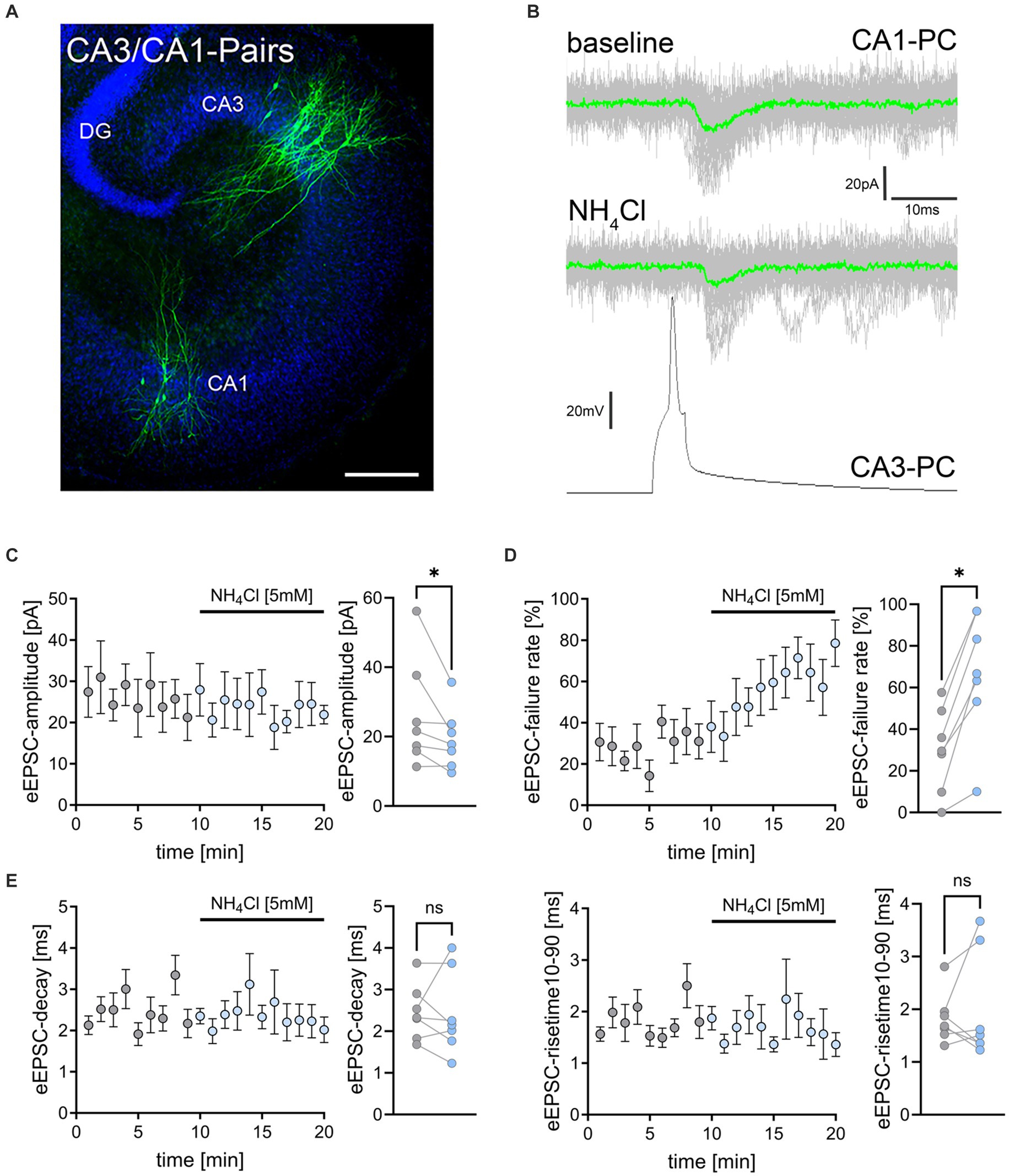

Synaptic effects of ammonium chloride in CA3/CA1-paired recordingsTo further validate and extend our findings on the effects of NH4Cl on excitatory neurotransmission, we conducted simultaneous whole-cell patch clamp recordings on connected pairs of CA3 and CA1 pyramidal neurons (Figure 3A). Action potentials were induced in CA3 neurons at 0.1 Hz, while evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) were recorded from CA1 neurons (Figure 3B). Neuronal pairs were considered connected when >5% of presynaptic action potentials triggered time-locked eEPSCs within 10 ms after action potential induction. Following 10-min baseline recordings, 5 mM NH4Cl in ACSF was introduced (c.f., Figure 1C). In these experiments we observed a slight but significant reduction in eEPSC amplitudes after wash-in of NH4Cl (Figure 3C). Additionally, there was a significant increase in synaptic failure rates, with the percentage of action potentials not evoking postsynaptic responses rising from 24.7 ± 6.51% to 67.1 ± 11.42% (Figure 3D; mean ± SEM, n = 7 pairs from 7 cultures; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test comparing mean values of first 5 min (baseline) and last 5 min (wash-in) in each pair; p = 0.016). However, eEPSC decay times and rise times were not significantly affected (Figure 3E). These findings confirmed that NH4Cl impacts excitatory synaptic transmission.

Figure 3. NH4Cl reduces the amplitude and increases the failure rate of eEPSCs on CA3-to-CA1 synapses. (A) Post hoc staining (green) of patched and simultaneously recorded pairs of CA3 and CA1 pyramidal neurons. TO-PRO (blue) was used to visualize cytoarchitecture (DG, dentate gyrus; CA1, Cornu Ammonis 1; CA3, Cornu Ammonis 3) Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Averaged responses of successfully evoked time-locked postsynaptic currents from CA1 neurons. Action potentials were induced at 0.1 Hz in presynaptic CA3 pyramidal neurons while recording evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) from CA1 neurons. (C–E) Data of amplitude (C), failure rate (D), decay and risetime (E) of eEPSCs before (gray) and during (blue) exposure to 5 mM NH4Cl [n = 7 pairs from 7 cultures; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test comparing mean values of first 5 min (baseline) and last 5 min (wash-in) in each pair; pamplitude = 0.016; pfailure rate = 0.016]. Values represent mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

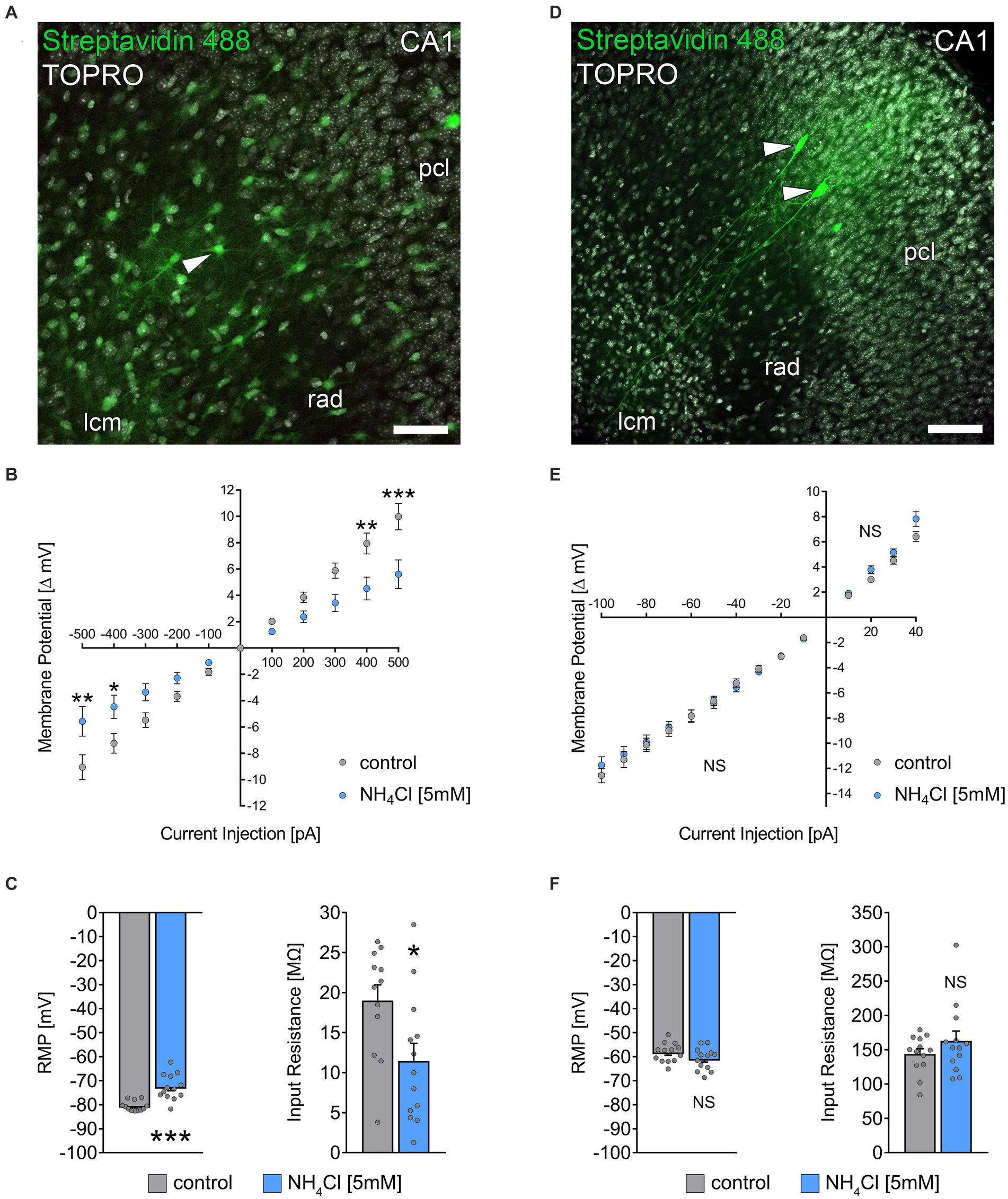

NH4Cl alters the passive membrane properties of astrocytes while leaving membrane properties of CA1 neurons unaffectedPrevious research has shown that ammonia can cause astrocytic swelling (Jayakumar et al., 2009) and disrupt astrocytic glutamate uptake (Rose, 2006). Because we observed a reduction in excitatory neurotransmission, we wondered whether an effect on astrocytes was also present in our experimental setting. To investigate if NH4Cl affects astrocytic membrane properties, we patched individual astrocytes in stratum radiatum of the hippocampal CA1 region in control cultures exposed to ACSF-only and cultures exposed to ACSF containing 5 mM NH4Cl (for 10 min) immediately before recordings (Figures 4A–C). Interestingly, NH4Cl exposure resulted in an increased resting membrane potential (RMP) and decreased input resistance in astrocytes (Figures 4B,C). To determine the specificity of NH4Cl effect on astrocytes, we also recorded passive membrane properties of CA1 pyramidal neurons in ACSF-only or ACSF with 5 mM NH4Cl (different sets of cultures; 10 min; Figures 4D–F). These recordings showed no significant changes in RMP and input resistance between the two groups (Figures 4E,F), suggesting that at 5 mM NH4Cl specifically alters the passive membrane properties of astrocytes without significantly affecting those of CA1 neurons.

Figure 4. NH4Cl alters the passive membrane properties of astrocytes. (A) Post hoc staining of recorded biocytin-filled astrocytes (arrowhead) in the stratum radiatum of CA1. TO-PRO (gray) was used to visualize cytoarchitecture (pcl, stratum pyramidale; rad, stratum radiatum; lcm, stratum lacunosum-moleculare). Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Group data of input–output curves of astrocytes in non-treated and 5 mM NH4Cl-treated cultures (ncontrol = 12 cells from 3 cultures; nNH4Cl = 13 cells from 4 cultures; 2way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; p−500 = 0.003; p−400 = 0.037; p400 = 0.004; p500 < 0,001). (C) Group data of resting membrane potentials and input resistances of astrocytes in non-treated and 5 mM NH4Cl-treated cultures (ncontrol = 12 cells from 3 cultures; nNH4Cl = 13 cells from 4 cultures; Mann–Whitney test; pRMP < 0,001; pInput Resistance = 0.03). (D) Post hoc staining of recorded biocytin-filled CA1 pyramidal neurons (arrowheads). Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Group data of input–output curves of CA1 pyramidal neurons in non-treated and 5 mM NH4Cl-treated cultures (ncontrol = 13 cells from 4 cultures; nNH4Cl = 13 cells from 4 cultures; 2way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (F) Group data of resting membrane potentials and input resistances of CA1 pyramidal neurons in non-treated and 5 mM NH4Cl-treated cultures (ncontrol = 13 cells from 4 cultures; nNH4Cl = 13 cells from 4 cultures; Mann–Whitney test). Gray dots indicate individual data points, values represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

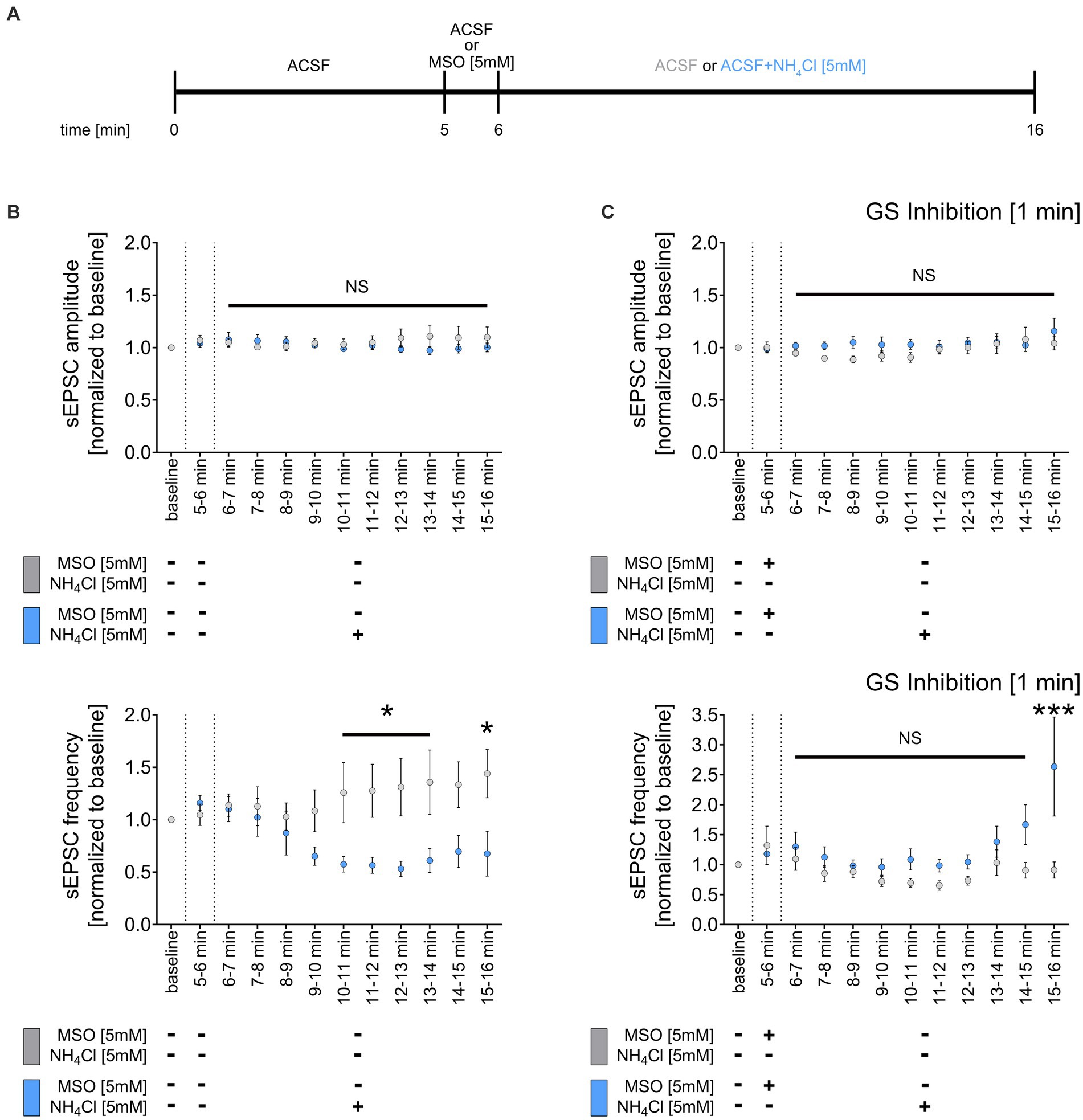

Inhibition of glutamine synthetase prevents the NH4Cl-mediated weakening of sEPSC frequencyGlutamine synthetase, primarily expressed by astrocytes in the central nervous system (Derouiche and Frotscher, 1991), is essential for ammonia and synaptic glutamate clearance (Suarez et al., 2002). We theorized that NH4Cl exposure might reduce sEPSC frequencies via astrocytic glutamine synthetase, which converts glutamate to glutamine when NH4Cl is present. This process potentially diminishes the availability of glutamate, impacting excitatory synapses. To test this, we initially recorded a 5-min sEPSC baseline, followed by a 1-min wash-in of ACSF containing 5 mM methionine sulfoximine (MSO) (Figure 5A), an irreversible inhibitor of glutamine synthetase (Jeitner and Cooper, 2014). Subsequently, we introduced either NH4Cl-containing or regular ACSF for 10 min (Figure 5A). As before, 5 mM NH4Cl reduced the mean sEPSC frequency without altering sEPSC amplitudes (Figure 5B). However, pre-treatment with 5 mM MSO did not affect sEPSC amplitudes and frequencies but did prevent the NH4Cl-induced decrease in sEPSC frequencies, even reversing it after 10 min (Figure 5C). The exact mechanism and reason for the increased sEPSC frequencies are currently unknown. Overall, these results suggest that the reduction of sEPSC frequencies is mediated through glutamine synthetase. This underscores the role of astrocytes in synaptic changes induced by NH4Cl.

Figure 5. Inhibition of glutamine synthetase prevents the NH4Cl-induced reduction of sEPCS frequency. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental design. Baseline was recorded for 5 min, followed by 1-min wash-in of 5 mM MSO or normal ACSF and a subsequent 10-min wash-in of 5 mM NH4Cl or normal ACSF. (B) Group data of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons after wash-in of 5 mM NH4Cl or normal ACSF (control) for 10 min (ncontrol = 9 cells from 6 cultures; nNH4Cl = 16 cells from 10 cultures; 2way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; p10-11 min = 0.049; p11-12 min = 0.034; p12-13 min = 0.013; p13-14 min = 0.021; p15-16 min = 0.017). (C) Group data of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons of tissue cultures exposed to 5 mM MSO for 1 min, followed by 10-min wash-in of 5 mM NH4Cl or normal ACSF (control) (ncontrol + MSO = 10 cells from 6 cultures; nNH4Cl + MSO = 12 cells from 7 cultures; 2way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; p15-16 min < 0.001). Values represent mean ± SEM (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, NS, not significant).

DiscussionThis study demonstrated that acute NH4Cl exposure reduces excitatory synaptic transmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons of organotypic slice cultures. While NH4Cl did not significantly alter the passive membrane properties of CA1 pyramidal neurons, it notably affected astrocytes by increasing their RMP and changing their membrane input resistance. The prevention of NH4Cl-induced reduction in excitatory synaptic activity by inhibition of glutamine synthetase suggests that this enzyme in astrocytes primarily mediates the detrimental effect of NH4Cl on excitatory synaptic transmission.

Prior research has examined the effects of NH4Cl on synaptic plasticity [reviewed in Wen et al. (2013)], with a focus on how sustained hyperammonemia affects activity-dependent synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) of excitatory neurotransmission (e.g., Citri and Malenka, 2008). For example, hyperammonemic states have demonstrated detrimental effects on tetanus-induced LTP in hippocampal slices obtained from hyperammonemic rats (Chepkova et al., 2017; Monfort et al., 2007; Munoz et al., 2000) and in cortico-striatal slices in a model of mild HE, specifically, portocaval anastomosis (Sergeeva et al., 2005). Acute NH4Cl exposure has disrupted LTP in acute hippocampal slices (Chepkova et al., 2006) and impaired LTD in the cortico-striatal pathway (Chepkova et al., 2012). Our experiments align with these findings, showing acute NH4Cl exposure leads to a reduction in sEPSC frequencies, increased synaptic failure rate and reduced amplitudes in connected CA3-CA1 neuron pairs (Lazarenko et al., 2017). The implications of our findings extend to the understanding of NH4Cl effects on synaptic plasticity: NH4Cl may alter neuronal activity responses to stimulation, which in turn could affect LTP and LTD induction. This does not necessarily reflect intrinsic changes in the neurons’ ability to express synaptic plasticity or alterations in LTP/LTD per se.

Another important aspect to consider is whether the chronic effects of NH4Cl are directly attributed to ammonia or if they partly reflect compensatory homeostatic mechanisms counteracting synaptic effects of NH4Cl. Indeed, chronic hyperammonemia has been linked to modifications of AMPA receptor composition, possibly indicating a postsynaptic compensatory response. Specifically, long-term ammonia exposure leads to the increased insertion of GluA2-containing, Ca2+-impermeable AMPA receptors into the membrane (Taoro-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Taoro-Gonzalez et al., 2019), influencing the ability of neurons to express plasticity crucial for learning and memory (Hollmann et al., 1991; Wiltgen et al., 2010). Our previous work suggested that activated microglia may mediate synaptic homeostasis, (Kleidonas et al., 2023), potentially affecting plasticity-induction under specific pathological conditions [for review: (Cornell et al., 2022; You et al., 2024)]. Moreover, microglia activation is associated with increased inhibition and synaptic plasticity alterations (Abareshi et al., 2016; Izumi et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2022; Lenz et al., 2020; Strehl et al., 2014), as observed in chronic HE (Sancho-Alonso et al., 2022a). It is evident that further investigation is required to clarify the interplay between NH4Cl exposure, changes in excitatory neurotransmission, microglia activation, and maladaptive homeostatic synaptic plasticity.

Alterations in the structure and function of astrocytes play a significant role in HE pathology (Claeys et al., 2021; Elsherbini et al., 2022; Jaeger et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2019). Traditionally, astrocytic swelling was attributed to ammonia exposure, but Rangroo Thrane et al. (2013) presented evidence challenging this view, suggesting that impaired potassium buffering by astrocytes underlies acute in vivo effects of ammonia. Compelling evidence underscores that ammonia prompts oxidative and nitrosative stress, specifically altering astrocytic but not neuronal functions (Gorg et al., 2019; Gorg et al., 2013; Haussinger et al., 2022; Lachmann et al., 2013). Our findings corroborate the vulnerability of astrocytes to NH4Cl; we observed that acute NH4Cl exposure results in hippocampal astrocytic depolarization and a decrease in their input resistance (c.f., Stephan et al., 2012). Notably, these alterations do not extend to the passive membrane properties of CA1 pyramidal neurons, contrasting observations in acute hippocampal slices (Kelly and Church, 2005). This may suggest that the neuronal effects of NH4Cl may vary between acutely prepared brain slices and organotypic tissue cultures, which are allowed an 18-day post-preparation recovery period. Thus, investigating the impact of NH4Cl on acutely lesioned networks in vitro, and in vivo could further elucidate the complex pathology of hyperammonemia, offering new insights into its effects on brain tissue. Regardless of these considerations, it remains to be shown whether the effects of NH4Cl on astrocytes and excitatory synaptic transmission reported in this study can be replicated in the hippocampus and other brain regions of the intact brain.

Despite these considerations, our research demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of glutamine synthetase mitigates the NH4Cl-induced reduction in sEPSC frequencies. This finding implies a significant recruitment of astrocytic glutamine synthetase early in NH4Cl exposure. Given that astrocytic glutamine synthetase plays a crucial role in converting ammonium and glutamate into glutamine (Rose et al., 2013), its activation supports the swift removal of glutamate from the synaptic cleft by astrocytes (Magi et al., 2019), which may affect synaptic activity. Excitatory amino acid transporters 1 and 2 (EAAT1 and EAAT2) on astrocytic plasma membranes might be involved in this process (Todd and Hardingham, 2020). However, further research is required to unravel the complex mechanisms and consequences of these findings, including the observed shifts in astrocyte RMP and input resistance. Determining whether the early heightened activity of glutamine synthetase, the suppression of excitatory transmission, and alterations in astrocyte RMP and input resistance culminate in compensatory maladaptive adjustments, and NH4Cl-induced dysfunctions during prolonged hyperammonemia remains a critical inquiry. We are confident that taking into account these temporal dynamics, along with the possible involvement of (microglia-mediated maladaptive) homeostatic plasticity, will aid in understanding the pathomechanisms of HE.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementThe animal study was approved by German animal welfare legislation and approved by the appropriate animal welfare committee and the animal welfare officer of Freiburg University (AZ X-17/07K). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributionsDK: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DH: Writing – review & editing. AV: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, CRC/974–Project-ID 190586431 B11).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2024.1410275/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | Osmolarity, but not the pH, of ACSF is affected by 5 mM NH4Cl. (A) Group data of pH values of: ACSF, ACSF with 5 mM NH4Cl, ACSF with 5 mM KCl, ACSF with 5 mM NaCl and ACSF with 10 mM sucrose (n = 5 samples per group; Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (B) Group data of osmolarity values of: ACSF, ACSF with 5 mM NH4Cl, ACSF with 5 mM KCl, ACSF with 5 mM NaCl and ACSF with 10 mM sucrose (n = 5 samples per group; Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; pNH4Cl = 0,009; pKCl <0,001; pNaCl <0,001; psucrose <0,001). Values represent mean ± S.E.M. (**p<0.001, *p<0.05; NS, not significant).

ReferencesAbareshi, A., Anaeigoudari, A., Norouzi, F., Shafei, M. N., Boskabady, M. H., Khazaei, M., et al. (2016). Lipopolysaccharide-induced spatial memory and synaptic plasticity impairment is preventable by captopril. Adv Med 2016, 7676512–7676518. doi: 10.1155/2016/7676512

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Adermark, L., Lagström, O., Loftén, A., Licheri, V., Havenäng, A., Loi, E. A., et al. (2022). Astrocytes modulate extracellular neurotransmitter levels and excitatory neurotransmission in dorsolateral striatum via dopamine D2 receptor signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 47, 1493–1502. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01232-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ali, R., and Nagalli, S. (2023). “Hyperammonemia” in StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing).

Balzano, T., Dadsetan, S., Forteza, J., Cabrera-Pastor, A., Taoro-Gonzalez, L., Malaguarnera, M., et al. (2020). Chronic hyperammonemia induces peripheral inflammation that leads to cognitive impairment in rats: reversed by anti-TNF-alpha treatment. J. Hepatol. 73, 582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bessman, S. P., and Bessman, A. N. (1955). The cerebral and peripheral uptake of ammonia in liver disease with an hypothesis for the mechanism of hepatic coma. J. Clin. Invest. 34, 622–628. doi: 10.1172/JCI103111

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Butz, M., Timmermann, L., Braun, M., Groiss, S. J., Wojtecki, L., Ostrowski, S., et al. (2010). Motor impairment in liver cirrhosis without and with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 122, 27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01246.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cabrera-Pastor, A., Hernandez-Rabaza, V., Taoro-Gonzalez, L., Balzano, T., Llansola, M., and Felipo, V. (2016). In vivo administration of extracellular cGMP normalizes TNF-alpha and membrane expression of AMPA receptors in hippocampus and spatial reference memory but not IL-1beta, NMDA receptors in membrane and working memory in hyperammonemic rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 57, 360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.05.011

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chepkova, A. N., Selbach, O., Haas, H. L., and Sergeeva, O. A. (2012). Ammonia-induced deficit in corticostriatal long-term depression and its amelioration by zaprinast. J. Neurochem. 122, 545–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07806.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chepkova, A. N., Sergeeva, O. A., Görg, B., Haas, H. L., Klöcker, N., and Häussinger, D. (2017). Impaired novelty acquisition and synaptic plasticity in congenital hyperammonemia caused by hepatic glutamine synthetase deficiency. Sci. Rep. 7:40190. doi: 10.1038/srep40190

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chepkova, A. N., Sergeeva, O. A., and Haas, H. L. (2006). Taurine rescues hippocampal long-term potentiation from ammonia-induced impairment. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Citri, A., and Malenka, R. C. (2008). Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Claeys, W., van Hoecke, L., Geerts, A., van Vlierberghe, H., Lefere, S., van Imschoot, G., et al. (2022). A mouse model of hepatic encephalopathy: bile duct ligation induces brain ammonia overload, glial cell activation and neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 12:17558. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22423-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Claeys, W., van Hoecke, L., Lefere, S., Geerts, A., Verhelst, X., van Vlierberghe, H., et al. (2021). The neurogliovascular unit in hepatic encephalopathy. JHEP Rep 3:100352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100352

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cornell, J., Salinas, S., Huang, H. Y., and Zhou, M. (2022). Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regen. Res. 17, 705–716. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.322423

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dallerac, G., Chever, O., and Rouach, N. (2013). How do astrocytes shape synaptic transmission? Insights from electrophysiology. Front Cell Neurosci 7:159. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00159

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Del Turco, D., and Deller, T. (2007). Organotypic Entorhino-hippocampal slice cultures—a tool to study the molecular and cellular regulation of axonal regeneration and collateral sprouting in vitro. Methods Mol. Biol. 399, 55–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-504-6_5

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

DeMorrow, S., Cudalbu, C., Davies, N., Jayakumar, A. R., and Rose, C. F. (2021). 2021 ISHEN guidelines on animal models of hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int. 41, 1474–1488. doi: 10.1111/liv.14911

留言 (0)