Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormally differentiated and long-lived myeloid precursors in the bone marrow and blood. Intensive chemotherapy in combination with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) can induce long-term remissions in only around 50% of AML patients and post-HCT relapse remains common (1–3). Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop novel maintenance therapies that stabilize remission.

Dendritic cell (DC)-based immunotherapy, which is either manufactured ex vivo and adoptively transferred or induced in vivo, is currently being explored as a potentially promising therapeutic option for AML (4–7). DCs are potent and multifaceted antigen presenting cells (APCs) which serve as a critical link between the innate and adaptive immune system. As sentinels of the immune system, DCs play an essential role in mediating efficient immune cell priming and stimulate leukemia specific innate and adoptive immune cells, thereby addressing blasts and installing memory cells (8–11). Moreover, DCs possess the unique ability to sense the surrounding microenvironment and initiate protective pro-inflammatory as well as tolerogenic immune responses (12). Considering the capacity of DCs to target a variety of antigens and especially by inducing memory cells, they possess the distinct ability to directly stimulate diverse immune cell subsets in a leukemia-specific manner in whole blood (WB). DC-mediated strategies could thus serve as potent maintenance therapies, since they have the ability to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD) (13).

Various auspicious DC generation methods have been developed that can overcome the lack of immunogenicity of AML cells. DCs can be propagated from monocytes in vitro (moDC) (14), pulsed with leukemic peptides (15), apoptotic leukemic cells or leukemic cell lysates (16), fused with leukemic blasts (17), or electroporated with messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) encoding leukemia-associated-antigens (LAA) and then prepared for injection as a vaccine (16). In our previous studies, we successfully generated DCs in near physiological conditions ex vivo using heparinized WB or whole bone marrow, containing patients’ (potentially immune activating or inhibiting) cellular or soluble factors under physiological hypoxia or normoxia (10, 18).

Leukemia-derived dendritic cells (DCleu) are characterized by the expression of costimulatory dendritic antigens and the patients’ individual leukemia-specific antigens. Standard generation of DC/DCleu is known to be possible with immunomodulatory Kits from leukemic or healthy WB without induction of blast proliferation (10, 19, 20). Such kits are composed of single drugs that have been approved for clinical use in patients with non-leukemic disease indications. For example, Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) analogs like misoprostol or alprostadil serve mainly as vasodilators and smooth muscle relaxants across several clinical conditions such as labor induction and maintaining the patency of the ductus arteriosus in neonates (21–23). A further example is OK-432 (or Picibanil) which is a lyophilized mixture of a low-virulence strain (Su) of group A streptococcus pyogenes incubated with the antibiotic benzylpenicillin (24). This potent immunostimulant has been utilized as a primary therapy in the treatment of lymphangiomas (25). With respect to any potential clinical application of these drug combinations in leukemia patients, optimal concentrations need to be identified.

Here, we aimed to refine the optimal concentration ranges of three different blast modulating Kits (Kit-M, -I, -K) required to generate sufficiently high frequencies of mature DC/DCleu directly from healthy or leukemic whole blood (WB) ex vivo. Moreover, the impact of these three different Kit-treated (DC/DCleu containing) WB samples on the mediation of immune (T-cell) activation, provision of (leukemia-specific) memory cells, anti-leukemic functionality and off-target cell toxicity were analyzed. This constitutes an important and directive step for translating DC/DCleu-based immunotherapy into clinical application.

Materials and methodsPatient characteristics, sample collection and preparationThis study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki protocol and the local Ethic Committee (VoteNo. #33905). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Peripheral blood was collected from AML patients (n=22) and from healthy volunteers (n=9) across multiple institutions (LMU University Hospital, Rotkreuzklinikum Munich, Augsburg, Oldenburg, Stuttgart). A detailed overview of patient features is provided in Table 1.

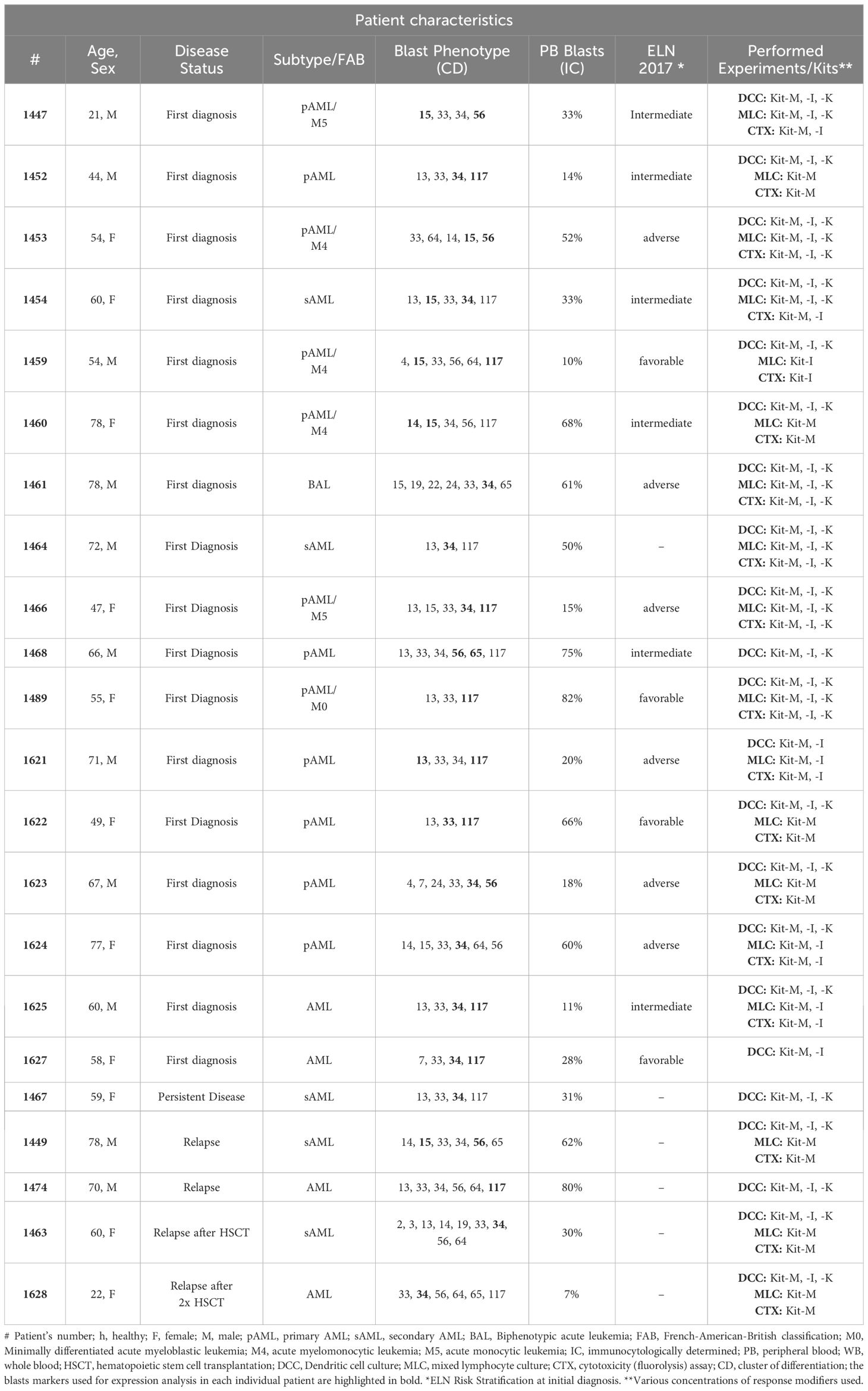

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Mononuclear cells (MNC) were isolated from WB by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. T-cells were isolated from MNC using the MACS microbead and column based immunomagnetic cell separation technology (Miltenyi Biotec) via positive selection of CD3+ cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions (19).

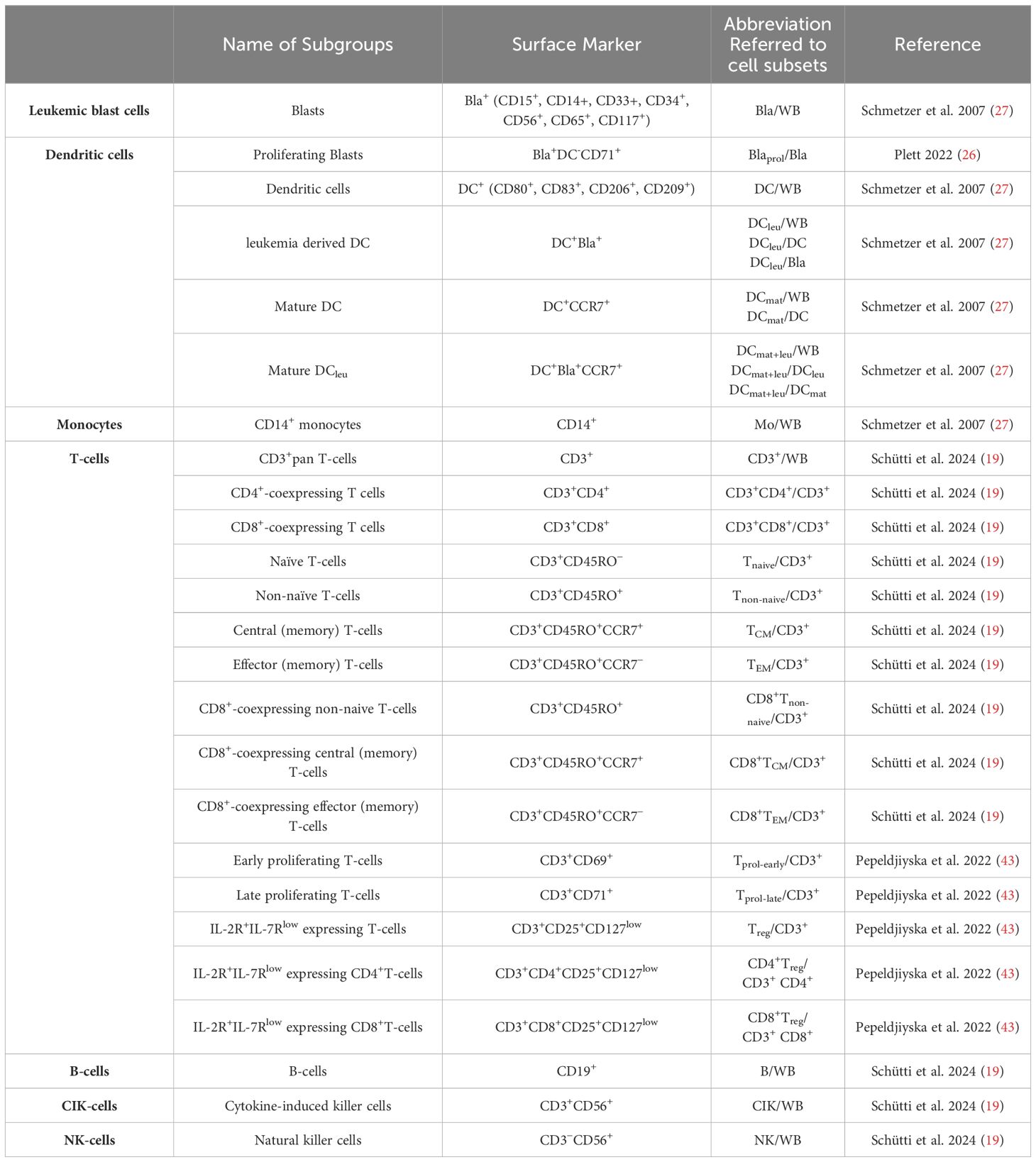

Immunophenotyping and cell characterization by flow cytometryFlow cytometric analyses were performed using a FACSCalibur four channel flow cytometer and the CellQuest Pro 6.1 software (Becton Dickinson) to evaluate and quantify frequencies, phenotypes and subsets of leukemic blasts, DCs, monocytes, NK-, CIK and T-cell subtypes, as shown before (9). Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 2. Flow antibodies for cell staining are outlined in the Supplementary Data Sheet 2.

Table 2. Cell types evaluated by flow cytometry.

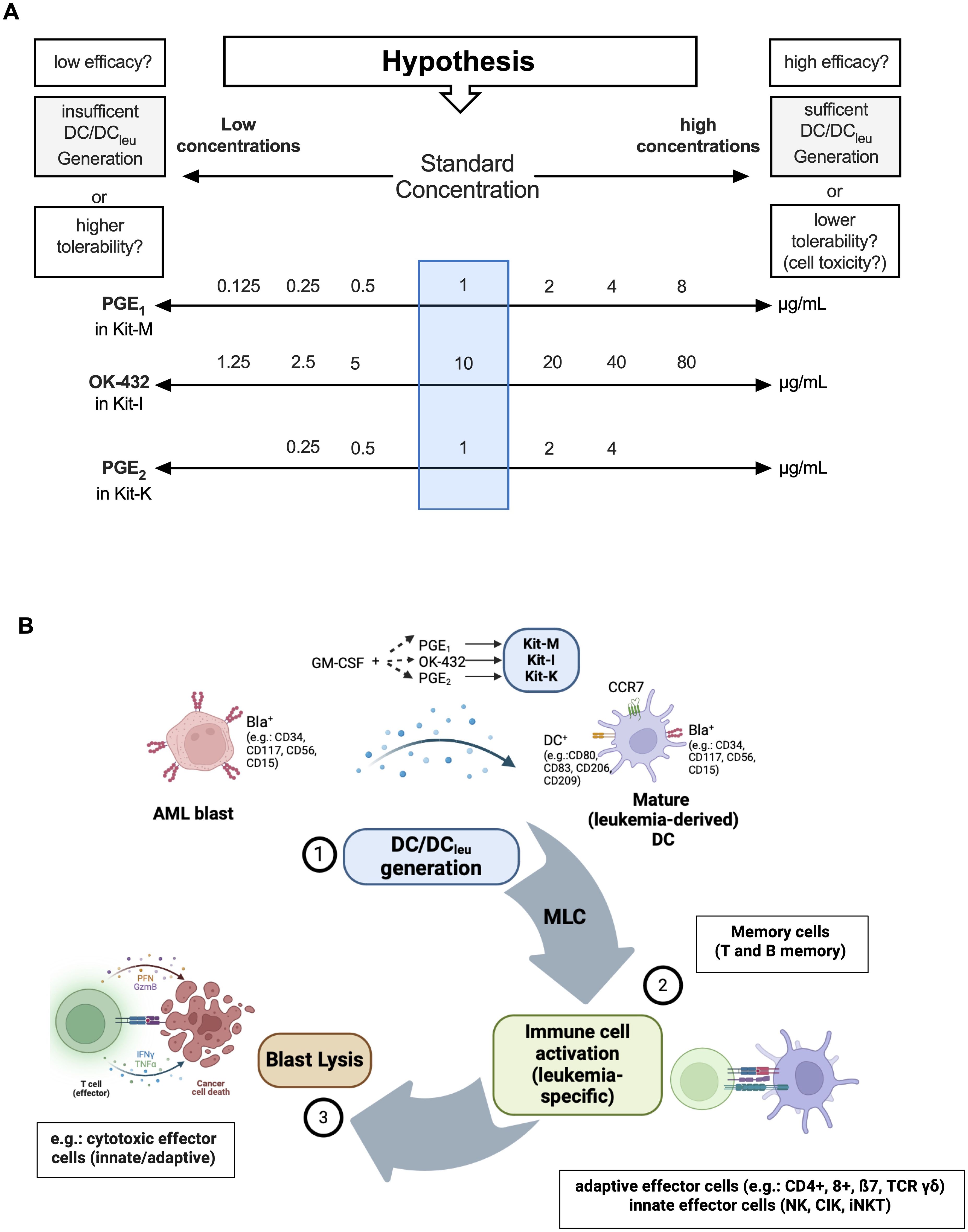

Dendritic cell cultureImmunomodulators were added to WB cultures as previously described (18). A culture without response modifiers served as negative control. Cells were harvested after 7-9 days. For AML DC cultures and DC cultures from healthy WB, we tested varying concentrations of PGE1 (0.125-8.0 μg/ml), OK-432 (1.25-80 μg/ml), and PGE2 (0.25-4.0 μg/ml). To study GM-CSF-independent differences of DC/DCleu generation and anti-leukemic functionality, a constant concentration of GM-CSF (800 U/ml) was applied across all protocols. The composition of DC/DCleu generating protocols (Kit-M, -I, -K) including the specific concentrations of the response modifiers are provided in Table 3 and Figure 1A.

Table 3. DC/DCleu-generating protocols with Kits.

Figure 1. DC/DCleu generation using different (concentrations of) response modifiers and mode of action of DC/DCleu-mediated antileukemic reactions. (A) Overview of the varying concentrations of response modifiers (PGE1, OK-432, PGE2) in addition to GM-CSF (800 U/ml) within DC/DCleu-generating kits. These were used to define the optimal concentration for each Kit to generate sufficient DC fractions in WB without off-target cell toxicity. (B) A schematic illustration of Kit induced DC/DCleu mediated blast lysis: DC/DCleu were generated from blast containing AML whole blood (WB), followed by T cell enriched mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC) and a functional cytotoxicity assay.

Flow cytometric analyses of leukemic blasts, DC, DCleu and DCmat followed a refined gating strategy (9, 26, 27). DCleu were analyzed by the co-expression of at least one blast marker including lineage-aberrant markers (e.g., CD117) and at least one DC marker not expressed on naïve blasts (e.g., CD80). Mature DC/DCleu were assessed by examining the co-expression of CCR7 on DC or DCleu. A schematic overview of the experimental strategy for DC/DCleu generation and flow cytometric analysis plan for identifying DCleu is demonstrated in Figure 1B.

Mixed lymphocyte cultureDC/DCleu containing Kit treated WB culture (DCC) from dendritic cell culture were used to stimulate immune cells in T-cell enriched MLC as shown before (10, 19).

Cytotoxicity fluorolysis assayBlast lytic activity of T-cell enriched immunoreactive cells was measured after MLC with Kit treated WB-cultures. To this end, a fixed fraction of MLC containing 1×106 T-cells (as effector cells) and 1×106 thawed autologous leukemic blasts (as target cells) was employed. As a control, effector and target cells were cultured under the same conditions but separately and only combined prior to flow cytometric analyses. The achieved blast lytic activity was defined as the percentual difference of viable 7AAD negative target cells (blasts) between the cocultured vs not cocultured effector/target cells (9). Cytotoxic effects against T-cells, labeled as target cells, were analyzed in order to quantify potential T-cell toxic effects.

Statistical methodsData are presented as mean ± 95% confidence intervals, standard deviation (SD) or standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical tests are provided in figure legends (Wilcoxon matched paired signed rank test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for standard concentrations, Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test and Tukey’s multiple comparison test for concentrations, Spearman’s test for correlation analyses). Statistical significance was defined as ‘not significant’ (p>0.10), ‘borderline significant’ (*p<0.1), ‘significant’ (**p<0.05), ‘very significant’ (***p<0.01), or ‘highly significant’ (****p<0.001). Statistical analyses and figures were implemented using Prism 10.4.0 (GraphPad Software) and “bioRender.com”.

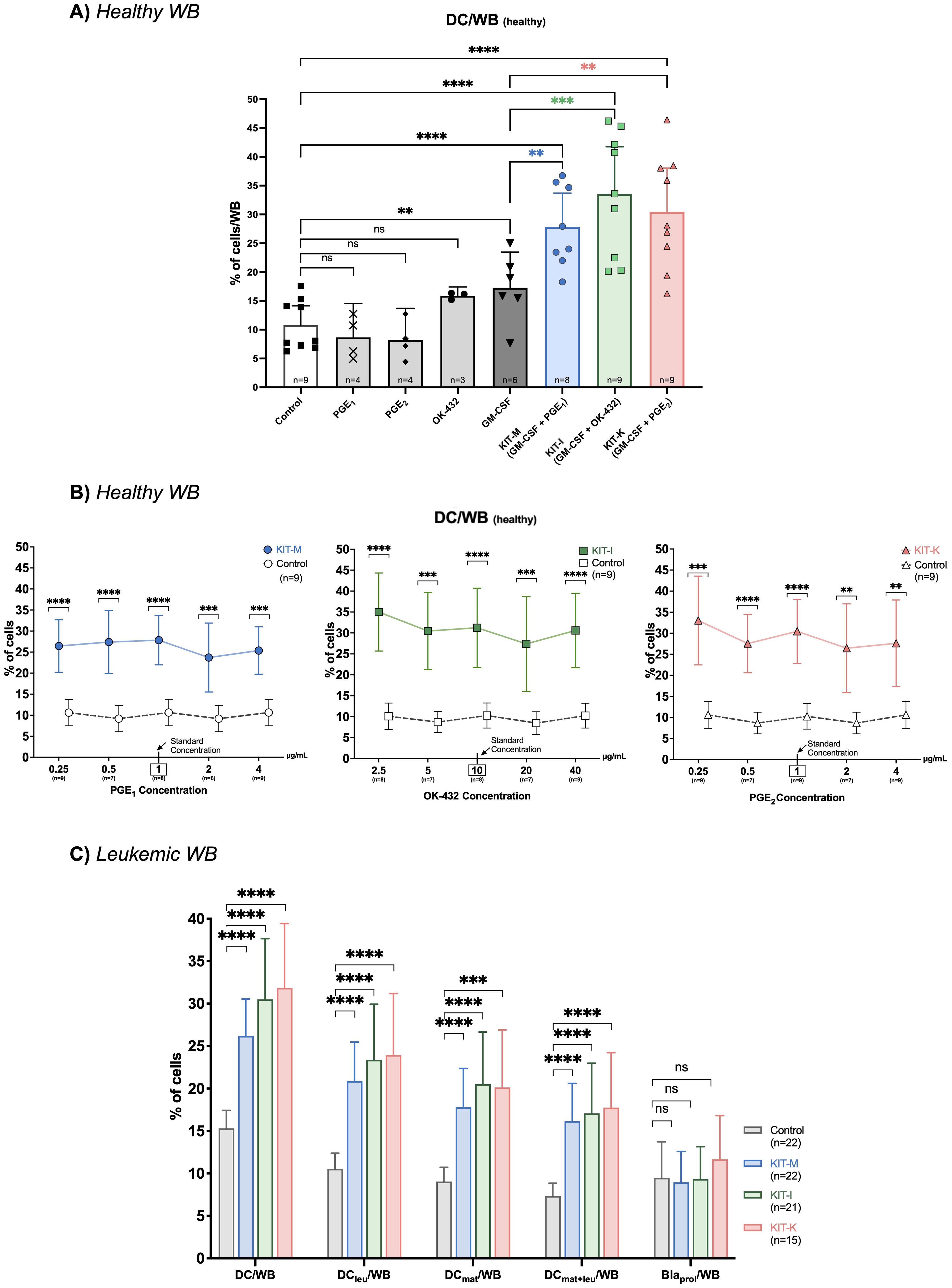

ResultsIncreased generation of (mature) DCs from healthy WB with standard concentrations of Kit-M, Kit-I and Kit-K, but not with single response modifiers aloneCompared to a control without response modifiers, we could generate significantly higher frequencies of (mature) DCs from healthy WB with immunomodulatory Kits in standard concentrations including Kit-M (GM-CSF, PGE1), Kit-I (GM-CSF, OK-432), and Kit-K (GM-CSF, PGE2) (Figure 2A). However, we did not observe increased (mature) DC generation compared to control when cells were stimulated with single response modifiers.

Figure 2. DC-generation using single or combined response modifiers. Frequencies of generated DCs from healthy (A, B) or leukemic WB (C) following treatment with different response modifying agents. (A) DC generation using either single response modifiers or Kits in standard concentrations of GM-CSF and PGE1 (Kit-M:  ), GM-CSF and OK-432 (Kit-I:

), GM-CSF and OK-432 (Kit-I:  ), or GM-CSF and PGE2 (Kit-K:

), or GM-CSF and PGE2 (Kit-K:  ). (B) DC generation using Kits with fixed standard concentrations of GM-CSF (800 U/mL) and varying concentrations of PGE1 (Kit-M), OK-432 (Kit-I), and PGE2 (Kit-K) (from left to right). A box and arrow indicate the respective standard concentration. (C) Generation of DC subsets from leukemic WB with standard concentrations of Kit-M, Kit-I and Kit-K vs. control. Abbreviations of DC cell subtypes are given in Table 2. Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Bonferroni’s and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were performed to calculate statistics, ****p<0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

). (B) DC generation using Kits with fixed standard concentrations of GM-CSF (800 U/mL) and varying concentrations of PGE1 (Kit-M), OK-432 (Kit-I), and PGE2 (Kit-K) (from left to right). A box and arrow indicate the respective standard concentration. (C) Generation of DC subsets from leukemic WB with standard concentrations of Kit-M, Kit-I and Kit-K vs. control. Abbreviations of DC cell subtypes are given in Table 2. Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Bonferroni’s and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were performed to calculate statistics, ****p<0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

To address whether DC-generating effects are predominantly driven by GM-CSF alone, we compared the frequencies of generated DCs induced by only GM-CSF with the Kit-M, Kit-I and Kit-K groups. Indeed, we noted significantly higher frequencies of (mature) DCs were generated from healthy WB with the immunomodulatory Kits in standard concentrations compared to GM-CSF alone (Figure 2A).

Increased generation of (mature) DCs from healthy WB with GM-CSF combined with various combinations and concentrations of PGE1, PGE2 or OK-432Next, we evaluated how the concentrations of immunomodulatory agents within each Kit impact DC generation. We added five different concentrations of PGE1, PGE2 or OK-432 to DC-cultures from healthy WB, while maintaining a constant GM-CSF concentration. Compared to control, significantly more DCs could be generated from healthy WB with PGE1 and PGE2 at concentrations ranging between 0.25-4 μg/mL (for Kit-M and Kit-K), and for OK-432 concentrations ranging between 2.5-40 μg/mL (for Kit-I). While we noted notable differences in the frequencies of generated DCs compared with control, we did not detect a significant difference when comparing the different response modifier concentrations against each other (p >0.1 for each cross-concentration comparison). The respective percentual differences in DC-frequencies vs. control are outlined in Figure 2B. Similarly, we could generate significantly higher frequencies of mature DCs (DCmat) and monocyte derived DCs (Mo-DC) at the same concentration ranges compared to control (Supplementary Figure S1).

Increased generation of mature and leukemia-derived DCs from leukemic WB across multiple immunomodulatory KitsWe were able to generate significantly higher frequencies of DCs and specific DC subtypes (e.g. DCleu, DCmat, DCmat+leu) from leukemic WB with all three immunomodulatory kits compared to the control without concurrent induction of blast proliferation (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S2) – using previously established standard concentrations (26). For example, we noted an approximately two-fold increase in the generation of (mature) DCleus compared to the control for each of the kits (Figure 2C, left). Furthermore, the relative frequencies of DC, DCleu, and DCmat+leu and their subsets did not significantly differ between Kits.

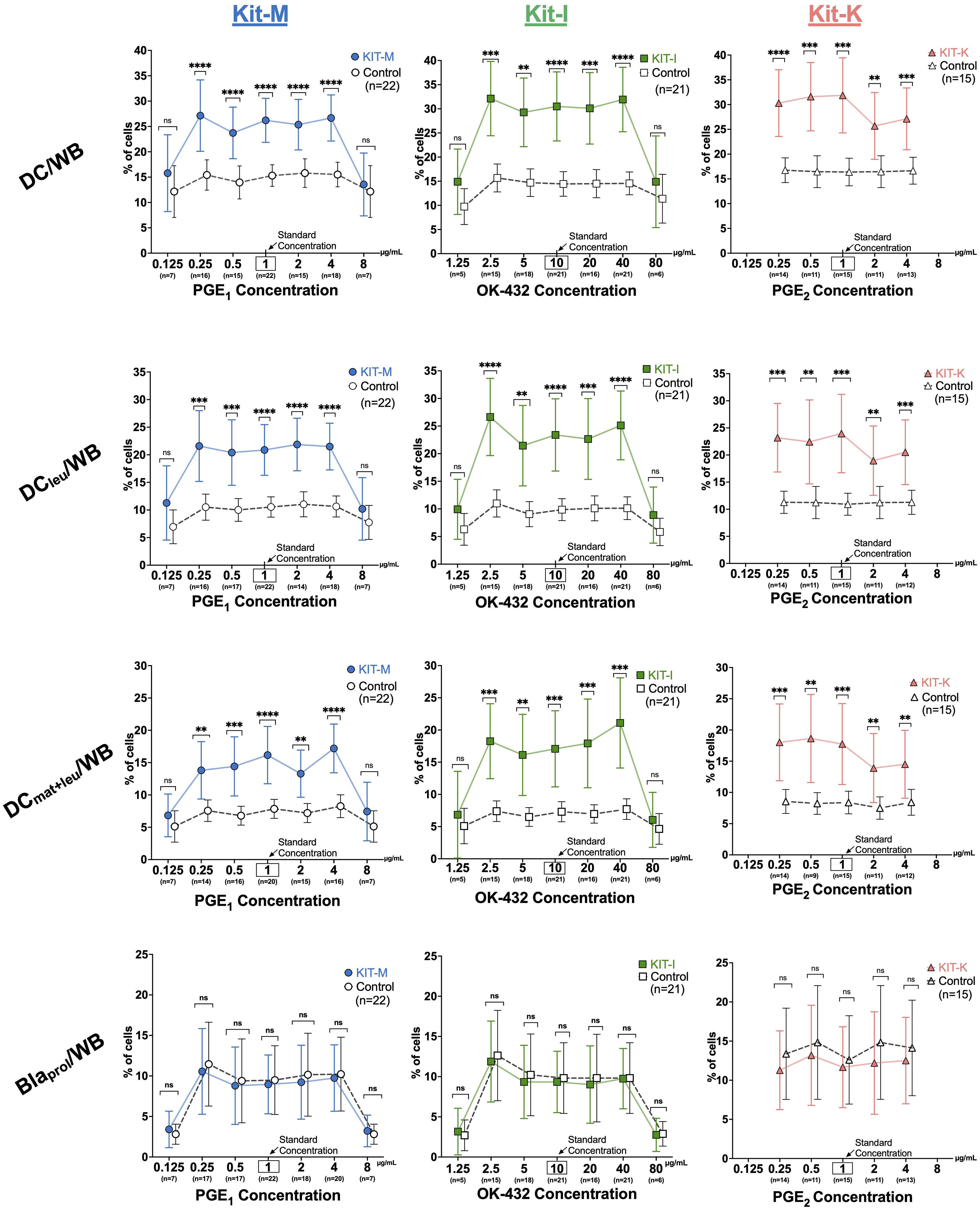

Increased generation of DC-subsets from leukemic WB according to concentrations of PGE1,2 or OK-432To assess how changes of response modifier concentrations impact DC generation from leukemic WB, we analyzed seven different concentrations of PGE1 (0.125-8 μg/mL) and OK-432 (1.25-80 μg/mL) and five different concentrations of PGE2 (0.25-4 μg/mL), while maintaining a constant concentration of GM-CSF (800 U/mL). For PGE1 (Kit-M), the relative frequencies of (mature) DCs, DCleu, and DCmat+leu were significantly increased compared to control across five different concentrations (0.25 to 4 μg/mL) (Figure 3, left). Conversely, very low (0.125 μg/mL) or very high (8 μg/mL) concentrations of PGE1 did not give rise to increased DC values. Similar findings were noted for OK-432 (Kit-I) with optimal generation of DCs and DC-subsets at intermediary concentrations of 2.5-40 μg/mL OK-432, whereas very low or high (1.25 or 80 μg/mL) OK-432 concentrations did not yield increased DC values (Figure 3, middle). Of interest, we found that the DCleu (but not DCmat) numbers within the generated DCs were significantly increased relative to control for the higher (80 μg/mL, p = 0.04) but not lower OK-432 concentrations (1.25 μg/mL, p > 0.9), as outlined in Supplementary Figure S3. Additionally, the higher relative ratio of DCleu to blasts was maintained with the higher concentrations of OK-432 (80 μg/mL) in Kit-I. For PGE2 (Kit-K), lower concentrations between 0.25-1 μg/mL yielded the highest frequencies of DCs and DC subsets (Figure 3, right). Nonetheless, higher concentrations of PGE2 still showed increased DC values compared to the control. Importantly, none of the kits resulted in increased blast frequencies relative to control, irrespective of the applied concentrations of the response modifiers (Figure 3, lowest row). Comparable findings for all three Kits and varying concentrations of the response modifiers were found for further DC-subtypes (DCleu/DC, DCmat+leu/DC, DCleu/Bla, Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 3. Generation of DC subsets from leukemic whole blood with varying response modifier concentrations. From left to right: Frequencies of DC subsets and proliferating blasts in leukemic whole blood (WB) for Kit-M ( ), Kit-I (

), Kit-I ( ), Kit-K (

), Kit-K ( ) using a constant concentration of GM-CSF (800 U/mL) and varying concentrations of PGE1, OK-432 and PGE2, respectively. Abbreviations of cell subtypes are provided in Table 2. Data are presented as mean ± 95% confidence intervals. Bonferroni’s and Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were performed to calculate statistics, p-values are shown above the line graphs, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

) using a constant concentration of GM-CSF (800 U/mL) and varying concentrations of PGE1, OK-432 and PGE2, respectively. Abbreviations of cell subtypes are provided in Table 2. Data are presented as mean ± 95% confidence intervals. Bonferroni’s and Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were performed to calculate statistics, p-values are shown above the line graphs, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

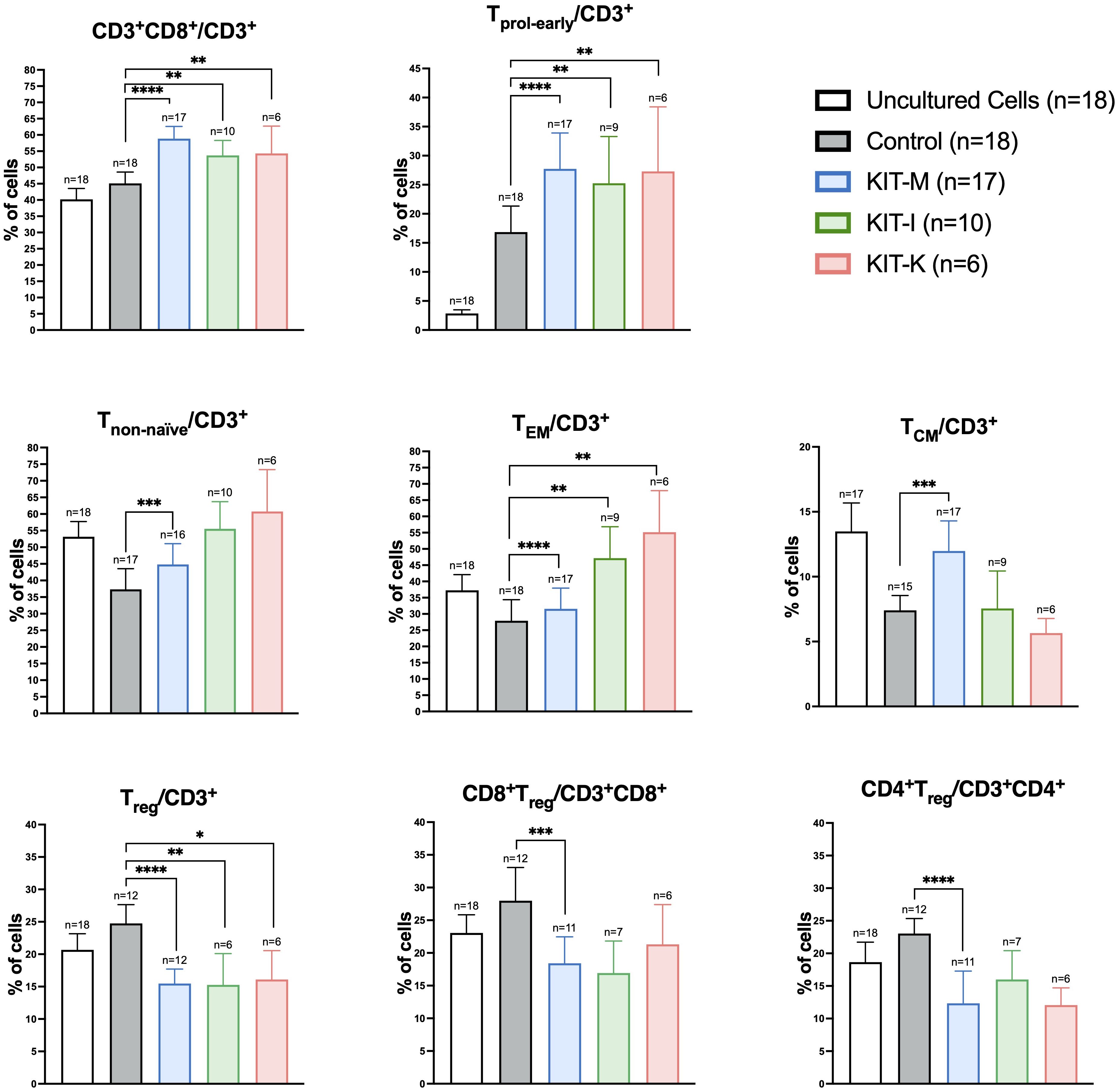

To further assess the DC/DCleu stimulating effects on immunoreactive cells in the presence of IL-2, we compared T-cell subtype compositions in CD3+ T-cell fractions before (uncultured cells) and after T-cell enriched MLC with Kit treated vs. untreated WB (MLCControl, MLCKIT-M, MLCKIT-I, MLCKIT-K). As previously demonstrated (9, 19), we found significantly increased frequencies of activated (proliferating, non-naïve) and memory (TEM, TCM) T-cells, but reduced frequencies of regulatory T-cells (Treg) in Kit pretreated vs. non-pretreated settings (Figure 4). Of interest, we only observed an increase of TCM cells with Kit-M (~two-fold increase). In addition, downregulation of CD4+ and CD8+ Treg cells was restricted to Kit-M, although this observation may have been facilitated by lower case numbers for Kit-I and Kit-K.

Figure 4. Kit-treated leukemic whole blood in mixed lymphocyte culture. Frequencies of T-cell subsets before (uncultured cells) and after T-cell enriched mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC) with Kit-treated or untreated (control) whole blood. Standard concentrations of PGE1, OK-432 and PGE2 were applied for Kit-M, -I, respectively (in addition to GM-CSF). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Wilcoxon matched paired signed rank test was performed to calculate statistics, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns). Abbreviations of cell subtypes are given in Table 2.

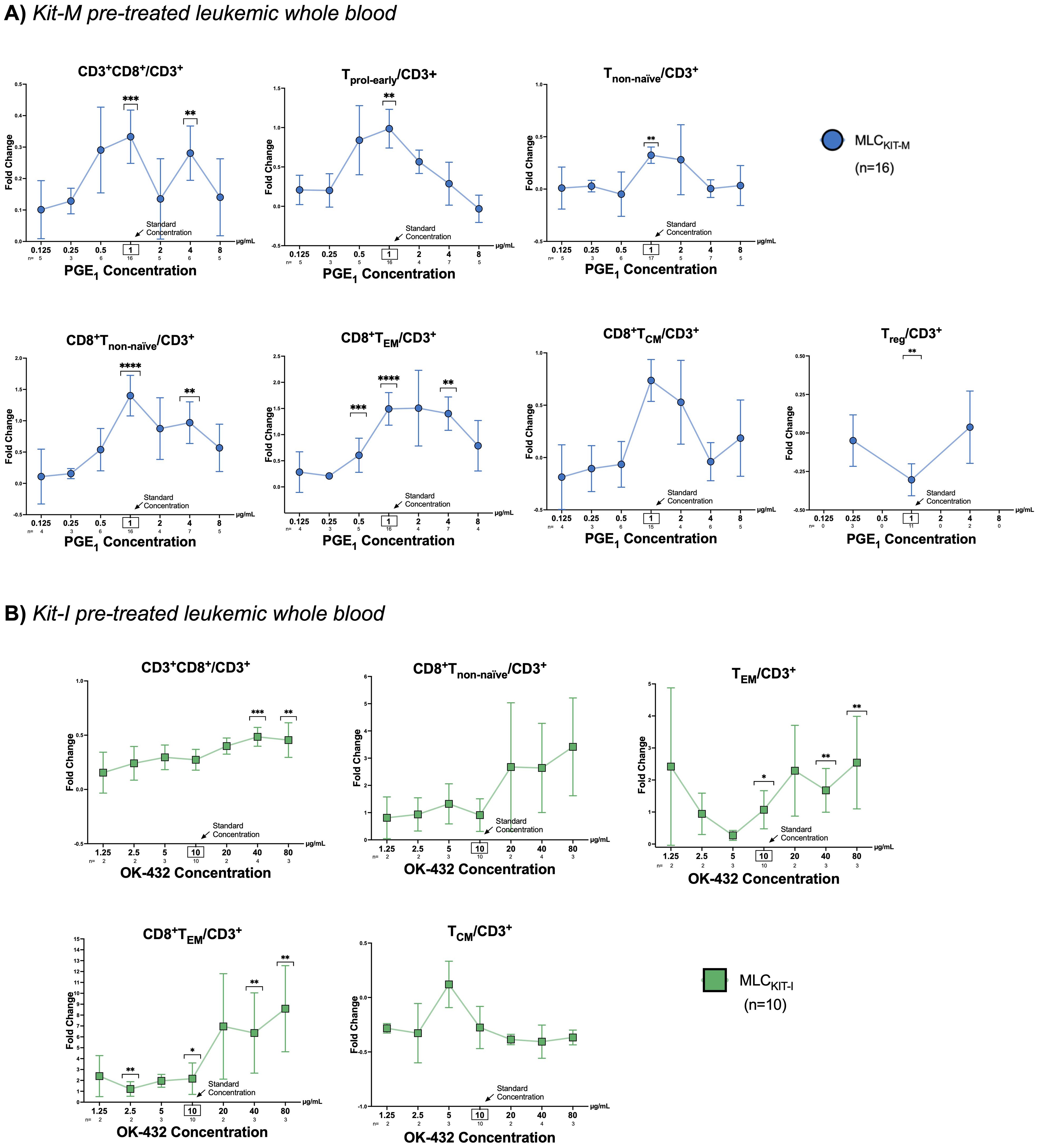

Increased frequencies of activated and memory T cell subsets after MLC with Kit pretreated leukemic WB are dependent on concentrations of PGE1,2 or OK-432Next, we analyzed T-cell subtypes in Kit pretreated vs untreated leukemic WB (used as stimulator cells in MLC) in the context of varying concentrations of PGE1, PGE2 or OK-432 (Figure 1). Representative flow cytometry scatter plots and the gating strategy to identify activated and memory T-cell subsets are outlined in Supplementary Figure S4. Compared to control samples that were not pretreated with Kit-M, we noted a clear or even significant increase of the frequencies of proliferating, non-naïve, and memory T-cells (especially of CD8+ subtypes) for PGE1 concentrations ranging between 0.5-4 μg/mL. The respective fold changes in the frequencies of the different T-cell subtypes with Kit-M compared to untreated controls are outlined in Figure 5A. For Kit-M, the most notable fold changes were observed around the previously established standard concentration (1 µg/mL). In addition, we noted an inversion of the CD4+ to CD8+ ratio (in favor of CD8+) with Kit-M compared to control, and a particular increase of (CD8+) TEM relative to TCM at higher PGE1 concentrations (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 5. T-cell composition following mixed lymphocyte culture of Kit pre-treated and untreated leukemic whole blood. (A, B) Fold changes of frequencies of T cell subtypes in Kit pre-treated compared to non-Kit-pretreated leukemic WB samples using constant concentrations of GM-CSF and (A) varying concentrations of PGE1 (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 µg/ml) or (B) OK-432 (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 µg/ml). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test were performed to calculate statistics, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns). Abbreviations for cell subtypes are given in Table 2.

When examining T-cell subsets following MLC of Kit-I pre-treated leukemic WB, we found a clear or even significant increase of proliferating, activated or memory T-cells (especially of CD8+ subtypes) in direct correlation with higher OK-432 concentrations. Fold changes of the frequencies of particular T-cell subtypes compared to controls without pretreatment of response modifiers are given in Figure 5B. For Kit-I, the highest frequencies of activated T-cells were noted in concentration ranges above the standard concentration for OK-432 (i.e., above 10 µg/mL). Data with varying concentrations of PGE2 (Kit-K) could not be generated due to low sample numbers.

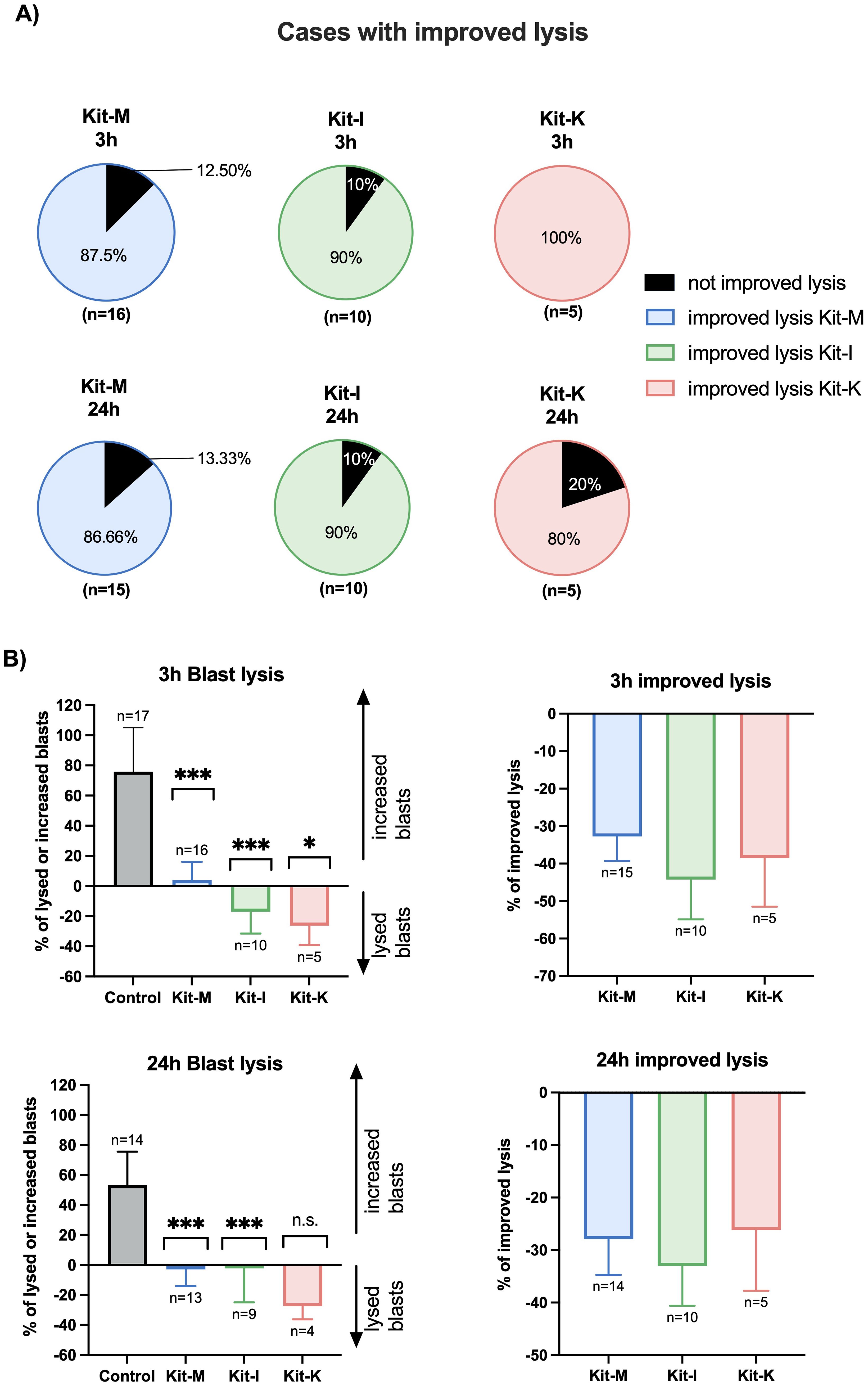

Improved blast lytic activity in a cytotoxicity assay with DC/DCleu stimulated T- and immune cellsTo assess blast lytic activity secondary to DC/DCleu stimulated T- and immune cells after MLC, we next performed cytotoxicity fluorolysis assays. Overall, we found improved blast lysis compared to the control for more than 80% of cases when using standard concentrations of Kit-M, -I, -K (Figure 6A) – consistent with prior findings (18, 19). The improved blast lysis after 3h and 24h of Kit-M, -I, -K pretreated samples vs control following MLC against blast target cells is provided in Figure 6A. The frequencies of lysed/increased blasts as well as improved blast lysis in all Kit treated samples compared to control are outlined in Figure 6B, confirming previous data (18).

Figure 6. Stimulatory effects of Kit-treated leukemic whole blood on the anti-leukemic activity of immunoreactive cells following MLC in a cytotoxicity assay. (A) Percentage of cases with improved blast lysis with Kit-M, -I and -K pretreated cells and untreated control following 3h and 24h of coculture of these effector cells with blast target cells. Standard concentrations of response modifiers were used for each Kit. (B) Average of lysed/increased blasts (left side) and improved blast lysis compared to control (right side). Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Wilcoxon matched paired signed rank test was performed to calculate statistics, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

At 3 hours, there was a statistically significant increase in blast lysis compared to the control across all three kits (Figure 6B, top left). Relative to the respective control sample, the highest improvement in blast lysis at 3 hours was observed for Kit-I (median 42% improvement in blast lysis), followed by Kit-K (38% improvement) and Kit-M (32% improvement) (Figure 6B, top right). At 24 hours, we confirmed reduced blast proliferation for the Kit-treated samples (Figure 6B, bottom left). Furthermore, all three Kits displayed improved blast lytic activity at 24 hours compared to control, which was highest for Kit-I (Figure 6B, bottom right).

Antileukemic cytotoxicity after MLC of Kit-treated (vs untreated) leukemic WB depends on response modifier concentrationsTo examine how different concentrations of response modifiers influence the antileukemic cytotoxicity propagated by the immunomodulatory kits, we performed cytotoxicity fluorolysis assays quantifying the improvement of blast lysis (vs control) in samples pretreated with varying concentrations of PGE1 (Kit-M: Figure 7, left) or OK-432 (Kit-I: Figure 7, right). For Kit-M, we identified significantly increased blast lysis compared to controls for PGE1 concentrations of 0.5-2 μg/mL following coincubation of effector with target cells for 3 hours and 24 hours, respectively (Figure 7, left). While we also noted increased blast lysis after 3 hours at higher PGE1 concentrations (4-8 µg/mL), this was accompanied by coincident death of T-cells. Moreover, diminished blast lysis and decreased T-cell proliferation at higher PGE1 concentration ranges was confirmed for Kit-M after 24 hours. In contrast, a direct positive correlation of increasing OK-432 concentrations (between 5-40 μg/mL) with improved blast lysis was seen without decreasing T-cell proliferation for Kit-I pretreated samples (Figure 7, right). Of interest, we noted a particular increase in T-cell proliferation at a higher OK-432 concentration of 40 µg/mL, which corresponded to high generation of DCs and DC subtypes with Kit-I (Figure 3) and was accompanied by significant blast lysis after 24 hours.

Figure 7. Anti-leukemic activity in a cytotoxicity assay according to varying response modifier concentrations. Stimulatory effects of Kit treated vs untreated leukemic whole blood (WB) using different concentrations of PGE1 or OK-432 and constant dose of GM-CSF in Kit-M or Kit-I on the anti-leukemic and anti-T cell activity of immunoreactive cells after MLC, as measured in a cytotoxicity assay (CTX). Provided are the percentages of improved blast lysis/proliferation and T-cell lysis/proliferation with Kit-M or Kit-I pre-treated vs untreated cells (after MLC) after 3h and 24h of co-culture of these ‘effector cells’ with blast target cells, respectively. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test were performed to calculate statistics, ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, <*p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

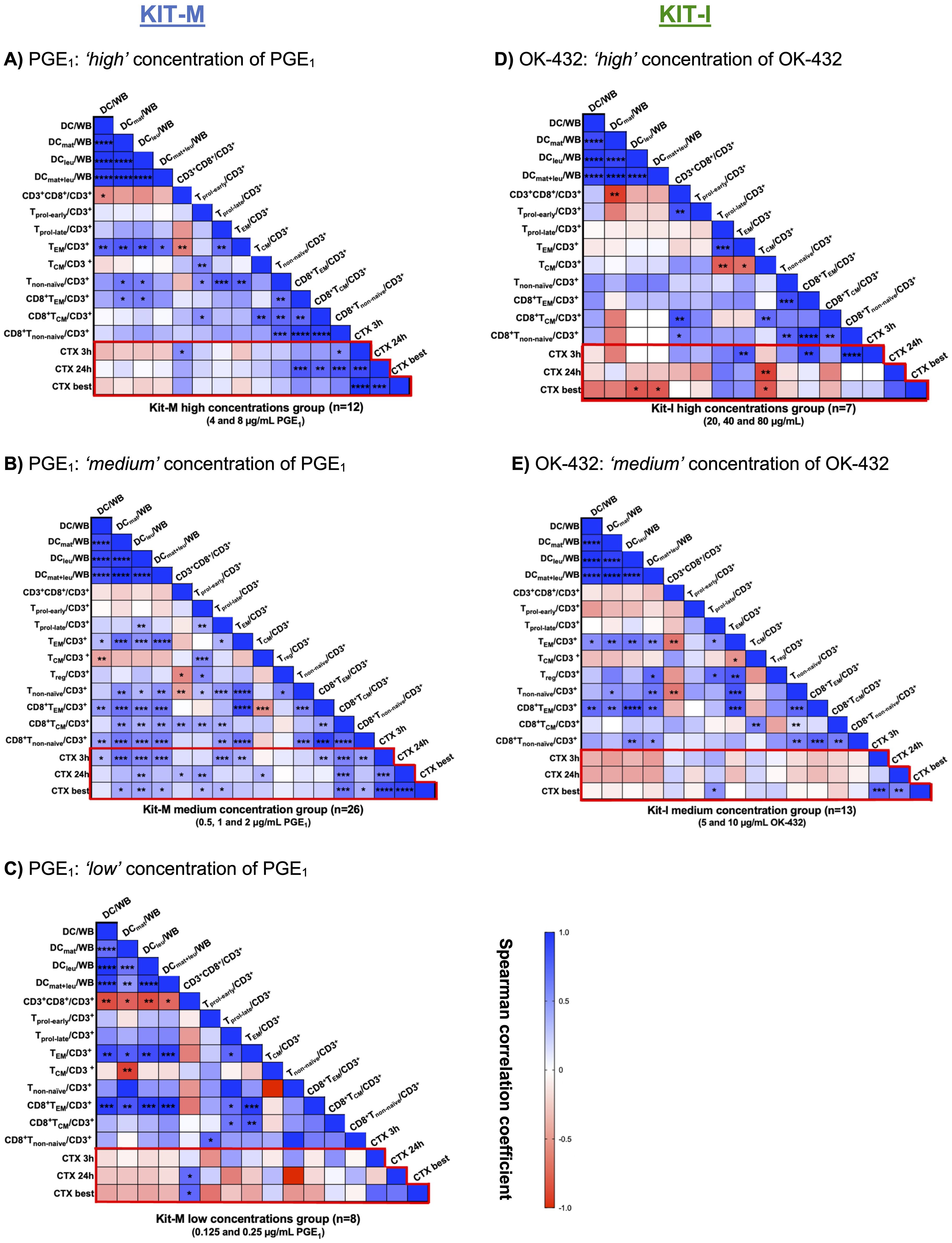

The frequencies of mature DCleu and activated T-cell subtypes associate with improved blast lysis in a concentration-dependent manner for PGE1 and OK-432To understand the association between Kit-mediated generation of DCs and activation of T cell subsets with the observed anti-leukemic effects, we performed a correlation analysis using the results from the cytotoxicity assay as the primary endpoint (Figure 8, red box). Based on the outcomes of the cytotoxicity assay, we aggregated results according to high, medium and low concentration ranges for PGE1 (Figures 8A–C) and OK-432 (Figures 8D, E).

Figure 8. Correlation analyses of generated DC and T-cell subsets with improved lysis in the cytotoxicity assay. (A–C) Leukemic whole blood (WB) treated with high (A), medium (B) or low (C) concentrations of PGE1 in Kit-M. (D, E) Leukemic WB treated with high (D) or medium (E) concentrations of OK-432 in Kit-I. The heat map analyses demonstrate the correlation between DC and T-cell subtypes (generated with Kit-M and Kit-I) and improved blast lysis (CTX assay) after 3 and 24 hours or choosing the best achieved improved lysis (CTX best). Spearman correlation tests were performed. Heatmap colors indicate positive (blue) vs. negative (red) correlation coefficients. Respective p values are shown for each comparison in the individual boxes ****p <0.001, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, 0.05<*p<0.1 borderline significant, p>0.1 not significant (ns).

Notably, we demonstrated (highly) significant correlations between the frequencies of (mature) DCleu and (CD8+) non-naïve T-cells and TEM/TCM in the ‘medium’ PGE1 concentration group (0,5-2 μg/mL), which were less pronounced in the ‘high’ (4-8 μg/mL) or the ‘low’ (0.125-0.25 μg/mL) PGE1 concentration groups (Figures 8A–C). Compared to the low and high concentration groups, we noted more extensive positive correlations between (mature) DCleu with activated T-cell populations in the ‘medium’ PGE1 concentration group. Moreover, the increased frequencies of (mature) DCleu correlated with improved blast lysis in the ‘medium’ PGE1 group (Figure 8B).

We demonstrated (highly) significant correlations between the frequencies of (mature) DCleu and (CD8+) non naïve T cells and TEM in the ‘medium’ (5-10 μg/mL), but not the ‘high’ OK-432 concentration group (20-80 μg/mL) (Figures 8D, E). We did not find a significant association between (mature) DCleu generation and improved blast lysis for both concentration groups. However, a positive association was noted for (CD8+) TEM and Tnon-naïve with improved blast lysis in the ‘high’ OK-432 concentration group (Figure 8D), while a negative association was observed between TCM and improved blast lysis.

DiscussionIn this preclinical study, we observed that DC/DCleu can be generated with three different immunomodulatory kits (e.g., Kit-M, -I, -K) from both healthy and AML whole blood and identified optimal ex vivo drug concentrations for efficient DC generation. After stimulation of immune cells in mixed lymphocyte culture with DC/DCleu containing Kit-treated whole blood, we observed specific patterns of immune cell and T-cell activation. Importantly, this translated into improved anti-leukemic activity and abrogation of blast proliferation.

Current therapeutic landscape of DC-based immunotherapyDendritic cells (DCs) serve as one of the most influential facilitators within the immune system, acting as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune system (28). These professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) possess the capacity to migrate into different tissues, can induce an immunological memory, and act as key initiators of tumor-specific immune responses. Because of these attributes, multiple strategies have been developed to target and/or utilize DCs for cancer immunotherapy, including the administration of antigens with immunomodulators that mobilize and activate endogenous DCs, as well as the generation of DC-based vaccines (28). Of interest, DCs can also play an important role in mediating host responses to other promising immunotherapies, as was demonstrated for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells in refractory solid tumors (29). Thus, DCs can be readily combined with other treatment modalities to enhance tumor-reactive lymphocyte populations (30, 31).

Challenges for immunotherapies in AMLGiven the lack of immunogenicity of AML blasts due to the inherently low tumor mutational burden (32) and the on-target/off-tumor expression of leukemia-associated antigens (LAAs) on non-leukemic myeloid cells, novel antigen-directed immunotherapies like bispecific antibodies or CAR T-cell therapy face significant hurdles in effectively targeting leukemic cells (33). Furthermore, these therapies are associated with a unique toxicity profile including cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity (ICANS), hematotoxicity and infectious complications (34–37). Due to the complex manufacturing procedures, they also exhibit relevant logistic and technical challenges and carry a high financial strain, limiting their broad use. Alternative treatment options are thus needed which are i) not restricted to specific LAAs and ii) easy-to-apply technically and logistically.

DC-based treatment for AMLOver recent decades, various methodologies have been devised to leverage DCs as a therapeutic approach for AML – a notoriously difficult disease to treat. Treatment of AML patients with manipulated DCs (loaded with leukemic antigens) has already shown promising effects with respect to inducing leukemia-specific reactions in vivo, resulting in subsequent stabilization of disease remissions (5, 30, 38, 39). However, the disadvantages of these approaches lie in the work- and cost-intensive production of manipulated DCs under GMP conditions, followed by the logistically challenging adoptive transfer of cells to patients (40). In contrast, our approach intends to convert (residual) blasts within the patients’ body to DCleu, thereby activating the immune system against the patients’ entire leukemic antigen repertoire directly in vivo. To this end, we have developed ‘Kits’ that contain (clinically approved) response modifiers, which generate DC/DCleu from leukemic WB and, moreover, hold the distinct ability of inducing antileukemic reactions following stimulation of immune cells in mixed lymphocyte culture (9, 19). In previous work, we could select the three Kits that best mediate antileukemic reactions (Kit-M/-I/-K) (18). In addition, we could demonstrate that Kit-I and -M exhibit superior capacity to induce antileukemic reactions (i.e., blast reduction) in leukemia-diseased rats (7). Notably, three therapy-refractory patients treated with Kit-M in an off-label rescue treatment were shown to produce leukemia-specific immune cells, accompanied by a decrease, or at least a stabilization, of the peripheral blast count [Anand, personal communication and (7)].

Concentration-dependent DC/DCleu generation and immune cell activationOur data show, that PGE1 leads to increased (DC/DCleu mediated) anti-leukemic ex vivo reactions in ‘medium’ but not in ‘low’ or ‘high’ concentrations (Figures 4, 8). High concentrations of PGE1 might even lead to T-cell-toxic effects (Figure 8). This would be consistent with the sensitivity of dendritic cells to immunometabolic and cytokine-mediated stressors, which can result in profound metabolic reprogramming (41). On the other hand, OK-432 added in various concentrations to leukemic WB samples (in addition to GM-CSF) did not exhibit as prominent off-target T-cell toxic effects, which can be interpreted in the context of the different modes of action of Kit-I vs Kit-M (e.g., favoring innate immunity) – as discussed in previous studies (9, 18). Importantly, in-depth correlation analyses supported our findings: only the ‘medium’ concentrations of PGE1 in Kit-M showed a strong correlation between DC subtypes and activated T cells, including reduced regulatory and induced memory T cells, which was also accompanied by significantly improved blast lysis. Accordingly, an optimal or homeostatic balance of TEM to TCM (and CD4 to CD8 T cells) may be critical to provide an effective pro-inflammatory immune milieu without resulting in excessive cytokine-mediated cytotoxicity. It should be noted that high concentrations of OK-432 (as high as 40 µg/mL) did not result in as extensive off-target cytotoxicity (Figure 8), highlighting differences in the concentration-dependent nature of immune cell activation compared to PGE1. With respect to Kit-K, our data might point to suboptimal generation of DC (subtypes) above 2 µg/mL, although data regarding the functional significance are missing due to low cell counts.

Anti-leukemic activity and clinical outlookWith respect to the further clinical development of Kit-based DC/DCleu-inducing treatment strategies, our data contribute important context: each Kit showed optimal concentration ranges that balanced encouraging effector cell activation and effective blast lysis. These advantageous concentration corridors of PGE1, PGE2, and OK-432 can now be tested in vivo or in proof-of-concept experiments in rodents. Our data highlight important pitfalls for clinical translation as too low concentrations of response modifiers may be ineffective, while too high concentrations may potentially be toxic (‘goldilocks’ principle) (42). It remains to be studied if blast lysis and clinical responses (or at least stabilization of the disease) can be achieved in off-label trials in patients with relapsed/refractory AML that are out of other treatment options. In general, our findings would argue for ramp-up dosing schedules that start at the lowest response modifier concentrations that were effective in generating DCleu while maintaining efficient blast lysis (e.g., 0.5 µg/mL for PGE1, 5 µg/mL for OK-432, 0.5 µg/mL for PGE2). Because current literature remains limited in regard to the precise translation of ex vivo to physiologic conditions, such strategies that ‘start low and go slow’ appear prudent.

ConclusionsIn summary, our ex vivo data show that varying the concentrations of response modifiers within immunomodulatory Kits (M, I, K) influences their capacity to generate (mature) DC/DCleu. Using Kit-pretreated leukemic WB samples to stimulate immune cells following MLC increases blast lysis compared to controls. Modulating the concentrations of PGE1 in Kit-M (‘medium’ concentration range) and OK-432 in Kit-I (‘high’ concentration range), we were able to increase (mature) DCleu generation, activate T effector and memory cells (after MLC), and improve blast lysis. Finally, correlation analyses revealed positive correlations of DC subtypes with T effector TEM/TCM cells and improved blast lysis especially for patient samples pretreated with ‘medium’ (standard) concentrations of PGE1.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by LMU Ethics Committee VoteNo. #33905. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsHR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. ER: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. LL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. CSchw: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. KR: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CSchm: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. AR: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JS: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. DK: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. PB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. HS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank all patients who contributed to the results in this study.

Conflict of interestModiblast Pharma GmbH Oberhaching, Germany holds the European Patent ‘EP 3,217,975 B10 and the US Patent ‘US 10,912,8200, in which HS is involved.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1527961/full#supplementary-material

References1. Rollig C. Improving long-term outcomes with intensive induction chemotherapy for patients with AML. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. (2023) 2023:175–85. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2023000504

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Sauerer T, Velazquez GF, Schmid C. Relapse of acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: immune escape mechanisms and current implications for therapy. Mol Cancer. (2023) 22:180. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01889-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Amberger DC, Schmetzer HM. Dendritic cells of leukemic origin: specialized antigen-presenting cells as potential treatment tools for patients with myeloid leukemia. Transfus Med Hemother. (2020) 47:432–43. doi: 10.1159/000512452

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Ansprenger C, Amberger DC, Schmetzer HM. Potential of immunotherapies in the mediation of antileukemic responses for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) - With a focus on Dendritic cells of leukemic origin (DCleu). Clin Immunol. (2020) 217:108467. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108467

留言 (0)