Since the discovery of the Hippo gene in Drosophila in the early 2000s (Tapon et al., 2002; Kango-Singh et al., 2002; Harvey et al., 2003; Udan et al., 2003; Pantalacci et al., 2003; Kim and Jho, 2018), intense investigations have revealed a role for the Hippo signaling pathway in modulating organ size regulation, tissue homeostasis, promoting stem cell differentiation, and cancer progression (Piccolo et al., 2013; Piccolo et al., 2023; Zheng and Pan, 2019; Chen et al., 2019; Driskill and Pan, 2023). In more recent years, research in genetics has identified Yes-associated protein (YAP) and paralog transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding domain (TAZ) as the key and major downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway (Ma et al., 2019), a signaling cascade that is evolutionarily preserved and controls numerous biological processes such as cellular proliferation, regulation of organ sizes, programmed cell death, and tissue regeneration. YAP/TAZ are transcriptional cofactors that play a crucial role in defining cellular outcomes, including differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Given their significance, YAP/TAZ regulate a wide array of physiological cellular mechanisms, positioning them as key factors in upholding tissue equilibrium and as potential therapeutic targets across various pathological contexts (Piccolo et al., 2023; Zarka et al., 2021; Dey et al., 2020). YAP/TAZ are not solely under the regulation of the Hippo pathway core kinases; additionally, they intercommunicate with various other signaling pathways including EGFR, WNT, TGF-β, and Notch, all of which play a role in processes related to development and cell proliferation (Lo Sardo et al., 2018; Zinatizadeh et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2024). The mechanical forces generated from cell–cell contacts, cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, and the tissue microenvironment have been recognized to also activate the YAP/TAZ transcriptional effector which further regulate gene transcription and thus coordinate cells during growth, proliferation, morphogenesis, migration, and cell death (Bissell and Barcellos-Hoff, 1987; Bissell and Aggeler, 1987; Zhu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2015; Miller and Sewell-Loftin, 2021; Cai et al., 2021; Dupont et al., 2011). Numerous studies have demonstrated the involvement of this pathway in the normal brain development, spanning the formation of the neural tube to the maturation and enhancement of the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and the ventricular system (Terry and Kim, 2022; Ouyang et al., 2020; Sahu and Mondal, 2021). The aberration of this pathway is prevalent in a variety of human malignancies where the essential nature of YAP/TAZ in regulating several key features of cancer has been widely observed. An extensive analysis of 9,125 tumor specimens unveiled a widespread dysregulation of the co-transcription factors YAP/TAZ across diverse cancer categories including medulloblastoma, glioma, neuroblastoma, colorectal, liver, lung, and pancreatic cancers (Sanchez-Vega et al., 2018). Recently, new studies have emerged implicating YAP/TAZ in neurodevelopmental disorders and defective neurogenesis which will be discussed later in this review. Findings from these studies suggest that the dysregulation of the YAP/TAZ signaling pathways may have a significant impact on the development of these disorders (Sahu and Mondal, 2021; Nussinov et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2020). Understanding the precise mechanisms by which YAP/TAZ contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders could provide new insights into their etiology and open potential avenues for therapeutic intervention.

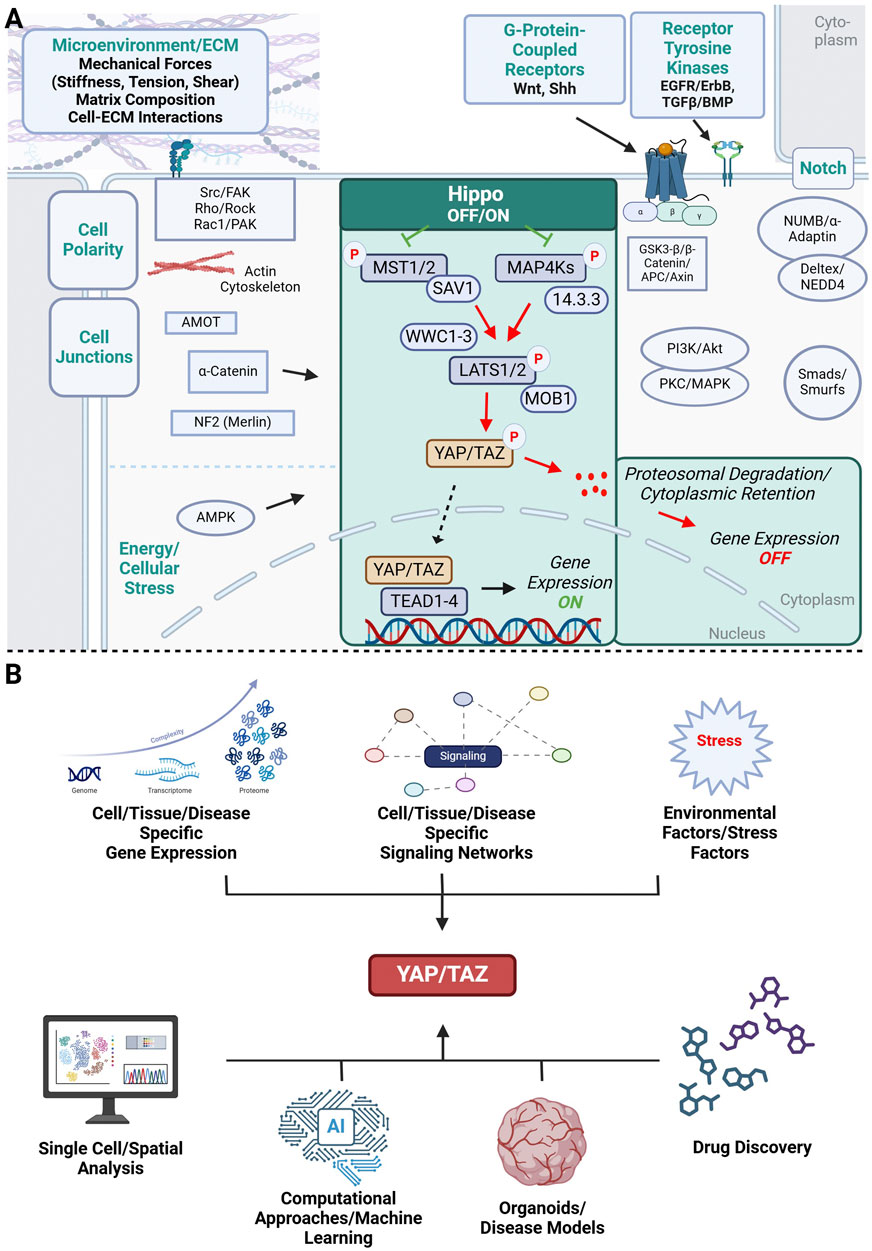

Overview of the Hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling pathwayThe Hippo pathway consists of a core kinase, effectors, cofactors, and transcription factors and is highly conserved in mammals (Hong et al., 2016). Cell contact, cell polarity, as well as metabolic and mechanical signals, undergo alterations throughout organ development and growth in order to effectively coordinate these highly complex processes, thereby regulating the function of the core components of the Hippo pathway (Panciera et al., 2017; Meng et al., 2016; Santinon et al., 2016). The Hippo pathway functions as a kinase cascade within cellular signaling mechanisms. Numerous investigations have demonstrated the significance of the Hippo signaling pathway in maintaining tissue homeostasis, promoting regeneration, and influencing the onset and progression of tumors (Dey et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2007). In mammals, activation of the canonical Hippo pathway results in the assembly of the sterile 20-like protein kinase (MST1/2; mammalian homologs of Hippo kinase) and Salvador 1 (SAV1)/WW45 complex, leading to the subsequent phosphorylation of the large tumor suppressor (LATS1/2)/Warts (Wts) and Mps One Binder kinase activator 1 (MOB1). Following this, the activated LATS1/2-MOB1 complex phosphorylates YAP/TAZ (Yorkie/Yki in Drosophila), causing their sequestration and breakdown in the cytoplasm. As a result, this mechanism prevents the accumulation of YAP/TAZ in the nucleus and the ensuing expression of downstream genes (Zhou and Zhao, 2018). The direct regulation of YAP/TAZ through LATS is defined as “canonical signaling”. This contrasts with the concept of “non-canonical signaling” used in recent studies to describe situations where the activity of YAP and TAZ is controlled independently of the LATS kinase. In addition to the canonical Hippo pathway, the MST1/2-SAV1-LATS1/2-MOB1-YAP/TAZ axis, other factors such as neurofibromin 2 (NF2) (Dong et al., 2007), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinases (MAP4Ks) (Meng et al., 2015), the cytoskeleton, focal adhesions (Dupont et al., 2011) and nuclear Dbf2-related1/2 (NDR1/2) (Meng et al., 2015) have been recognized as pathway regulators, thereby enhancing our understanding of the complexity of the Hippo signaling pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the YAP/TAZ signaling network. (A) Microenvironmental factors and cellular signaling networks that influence YAP/TAZ signaling and have been implicated in brain development, neurodevelopmental disorders and cancer. Highlighted in green is the canonical Hippo-YAP/TAZ-TEAD signaling cascade. Non-canonical YAP/TAZ activation is influenced by adjacent cells (cell polarity complexes, cell junctions, Notch signaling), microenvironmental factors such as mechanical forces (stiffness, tension, shear stress) and extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, and soluble signaling molecules triggering receptor tyrosine kinase (EGFR, TGF-β) and G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathways (Wnt, Shh). All these factors have been shown to influence normal brain development, can be dysregulated in neurodevelopmental disorders and promote cancer progression. Common intracellular signaling molecules relating extracellular factors to downstream YAP/TAZ activation are shown. (B) YAP/TAZ signaling is a complex signaling network that is controlled by cell- and tissue specific gene expression signaling networks and environmental factors beyond the cellular/tissue level contribute to the complex regulation of YAP/TAZ signaling. The complexity of this network will require multiplexed approaches when targeting YAP/TAZ in drug discovery including large-scale omics approaches that need to be integrated with representative disease models and computational methods for successful drug development. Illustration created in https://BioRender.com.

In contrast, when the Hippo pathway is turned off, dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ translocate to the nucleus where they interact with other transcription factors to modulate the transcription of downstream genes (Driskill and Pan, 2021). YAP/TAZ does not directly bind DNA; hence, they induce their biological functions through the formation of complexes with a different transcription factor known as TEAD (Transcriptional enhanced associate domain) DNA-binding family members (TEAD1-4). The expression of downstream target genes associated with the Hippo pathway (Wang et al., 2018; Totaro et al., 2018a), such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), ankyrin repeat domain 1 (ANKRD1), and MYC proto-oncogene transcription factor (MYC), plays a crucial role in regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival, migration and viability (Fu M. et al., 2022; Ehmer and Sage, 2016; Misra and Irvine, 2018). Dysregulation of the Hippo pathway occurs in a broad range of human carcinoma, including lung (Liang et al., 2024; Yoo et al., 2021), colorectal (Hong et al., 2016; Mouillet-Richard and Laurent-Puig, 2020), breast (Kyriazoglou et al., 2021), ovarian (Clark et al., 2022), pancreatic (Ansari et al., 2019), gastric (Seeneevassen et al., 2022), liver (Driskill and Pan, 2021) and brain (Ahmed et al., 2017; Masliantsev et al., 2021) cancer. It is important to note that YAP/TAZ undergo a continuous process of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, although the mechanism governing the activity of the phosphatases is not well known (Driskill and Pan, 2021). Recent research conducted in both Drosophila and mammalian cells utilizing live cell tracking techniques has revealed the rapid movement of Yki/YAP between the cytoplasm and nucleus (Ege et al., 2018; Manning et al., 2018). Changes in the Hippo signaling pathway have been observed to impact the phosphorylation of YAP, consequently affecting the rates at which YAP enters and exits the nucleus. This dynamic transportation of YAP is facilitated by nuclear pore complexes that are sensitive to mechanical signals, enabling the process of nuclear import and export (Li et al., 2023).

Other signaling pathways that activate and intercommunicate with YAP/TAZA cell functions as a dynamic entity where multiple processes take place concurrently. Specifically, the interaction between intra- and intercellular signaling pathways greatly influences various aspects of a cell’s biological processes such as its life cycle, differentiation, proliferation, growth, and regeneration, consequently affecting the normal operation of an entire organ. Communication between different signaling pathways plays a crucial role in modulating the key elements of the Hippo pathway and the localization of YAP/TAZ (Govorova et al., 2024). As mentioned earlier, YAP/TAZ can be activated and intercommunicate with other signaling pathways. The three major pathways that previous studies have shown to activate or intercommunicate with YAP/TAZ to regulate expression of downstream target genes involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis are the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/ErbB family, Notch, and Wnt signaling pathways.

EGFR/ErbB family signalingThe epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) consists of four members, EGFR/ErbB1/Her1, ErbB2/Her2, ErbB3/Her3 and ErbB4/Her4 and modulates an intricate signaling system involved in key cellular functions such as cell growth, cell division, cell migration, cell adhesion and apoptosis (Yarden and Pines, 2012; Citri and Yarden, 2006). Activation of the inherent kinase domain and phosphorylation on distinct tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tail are induced by the binding of ligands like EGF, amphiregulin, or HB (heparin binding)-EGF. The interconnection between the EGFR and Hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling pathways has been observed in a variety of conditions. For example, EGFR-dependent PI3K (phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase)-Akt signaling was discovered to serve as an upstream signal for the activation of YAP in the context of acute kidney injury (Chen et al., 2018) while ErbB2 drove YAP activation resulting in heart regeneration (Aharonov et al., 2020). Several groups described a link between EGFR signaling and the Hippo pathway in relation to the development of cancer, including in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Xia et al., 2018), lung cancer (Liang et al., 2024; Hsu et al., 2019) and breast cancer (Xu et al., 2024). The molecular links between EGFR and Hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling are varied. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells, one study demonstrated that the activation of EGFR results in the phosphorylation of one of the core Hippo pathway components, MOB1, which hinders the function of LATS1/2, consequently leading to the aberrant activation of YAP/TAZ independently of EGFR’s typical signaling targets, including PI3K (Ando et al., 2021). Zhang and Li (Zhang and Li, 2022) demonstrated that the activation of the EGFR pathway predominantly occurred through PI3K-PDK (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase) 1 signaling, circumventing the conventional RhoA pathway in favor of the Akt pathway to induce YAP activation in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. This was also seen in hepatocellular carcinoma where it was shown that EGFR mainly acts via PI3K-PDK1 signaling to activate and regulate YAP (Xia et al., 2018) whereas in glioblastoma, YAP nuclear translocation was regulated by EGFR through activation of the PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog)/Akt axis (Masliantsev et al., 2023). Blocking EGFR activity with AG1478 or EGFR knockdown in cervical cancer cells resulted in the elimination of YAP-induced cell proliferation (He et al., 2015). The authors demonstrated that the Hippo pathway interacts with the ErbB signaling pathway, establishing positive feedback signaling loop that plays a crucial role in regulating cervical cancer progression. Notably, HPV16 E6 inhibits the proteasome-dependent degradation of YAP, thereby sustaining the levels of YAP protein in cervical cancer cells and potentially promoting cancer cell growth (He et al., 2015). While our group has described a link between EGFR signaling and YAP involving Na,K-ATPase β2-subunit/AMOG (adhesion molecule on glia) and neurofibromin-2/Merlin in cerebellar granule cells (Litan et al., 2019), little is known about the interaction of EGFR and YAP in neurological diseases. However, recent studies have implicated Neuregulin 1 with its receptor ErbB4 in neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders (Shi and Bergson, 2020; Perez-Garcia, 2015; Adashek et al., 2024) and this pathway has been shown to interact with Hippo/YAP signaling (Haskins et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2017; Sudol, 2014).

Notch signalingThe Notch pathway is an evolutionary highly conserved signaling pathway that plays an important role in tissue and organ development. Unlike other well-known signaling pathways such as EGFR, Sonic hedgehog (Shh), Wnt, or BMP (bone morphogenetic protein)/TGF (transforming growth factor)-β signaling that mostly employ soluble ligands, Notch is activated through a transmembrane ligand/transmembrane receptor interaction of juxtaposed cells (Siebel and Lendahl, 2017; Zhou et al., 2022). Two primary modalities have been identified in the interaction between the YAP/TAZ and Notch signaling cascades: the regulation of Notch ligands or receptors by YAP/TAZ at the transcriptional level, and the co-regulation of common target genes by both YAP/TAZ and NICD (Notch intracellular domain) suggesting that there is a notable interplay between YAP/TAZ and the Notch signaling pathway (Totaro et al., 2018b).

There have only been a few studies that reported upstream regulation of YAP/TAZ activity via the Notch signaling pathway (Li et al., 2012; Slemmons et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2016). In murine neural stem cells, using gain- and loss-of-function experiments, findings indicated that the Notch signaling pathway exerts a positive upstream control on YAP activity, thereby regulating cell proliferation. Subsequent investigations unveiled that the RBPJ (recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J) transcription factor within the canonical Notch signaling pathway directly oversees the transcription of YAP1 protein by engaging its promoter sequence (Li et al., 2012). These investigators further noted that RBPJ could bind to TEAD2’s promoter sequence as well; nevertheless, this action alone was inadequate to initiate TEAD2 transcription. Correspondingly, similar outcomes were documented in research by Slemmons et al. (2017) on human rhabdomyosarcoma cells, employing gain- and loss-of-function methods to exhibit the upregulation of YAP activity by the Notch signaling pathway. Also, this study highlighted that the Notch signaling pathway may also facilitate YAP nuclear translocation. However, the underlying mechanism governing this process remains elusive, and it remains uncertain whether it involves the core Hippo signaling cascade (Slemmons et al., 2017). Conflicting results on this topic were showm by Lu et al. (2016), where despite confirmation that RBPJ directly binds to the YAP promoter, this action suppressed rather than stimulated YAP transcription. As a result, Notch signaling was found to promote the differentiation of the hepatic stem cells and simultaneously inhibiting their proliferation through the reduction of YAP activity (Lu et al., 2016). Other studies further highlight the complexity of the Notch and YAP/TAZ crosstalk within a single tissue. For example, one study showed that YAP positively upregulated Notch receptor Notch1 in hepatocytes which also revealed a novel YAP/TAZ-Notch1-NCID axis in hepatocytes and liver regeneration (Liu et al., 2019). Further, inhibition of YAP/TAZ signaling in vivo confirmed the impact of inhibiting this signaling pathway on liver regeneration. Additionally, the findings of this group indicated that inhibition of the YAP/TAZ signaling pathway resulted in a decrease in the protein levels of molecules linked to the Notch signaling pathway. This indicated a regulatory function of the YAP/TAZ pathway in influencing the Notch signaling pathway during liver regeneration (Liu et al., 2019).

Another recent study demonstrated that Notch and YAP/TAZ simultaneously upregulate the function of each other. Wang et al. (2024) showed that YAP/TAZ activated through cell-matrix interactions results in the transcriptional upregulation of Notch1 and Delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4). These molecules, in turn, served as direct positive regulators of the phenotype of the type H endothelial cells (THECs) in bone marrow endothelial cells (BMECs) following induction of distraction osteogenesis using tensile stress (TS). Concurrently, the Notch intracellular domain increased the activity of YAP/TAZ by boosting the transcriptional upregulation of YAP and the stabilization of TAZ protein, thereby establishing a correlation between YAP/TAZ and Notch (Wang et al., 2024). Finally, it is plausible that the specific regulation of YAP/TAZ activity by Notch signaling could exhibit variability based on the distinct cell types, relying on intricate interactions with other signaling mechanisms inherent in diverse cell lineages (Heng et al., 2021). As both Notch and YAP/TAZ signaling play an inherently important role in brain development, it is plausible that cell-type dependent crosstalk may influence the impact of these signaling pathways on neurodevelopmental disorders and brain cancers.

Wnt signalingThe Wingless (Wnt) signaling pathway is critical in regulating both embryonic development and tissue self-renewal (Liu et al., 2022; Steinhart and Angers, 2018). The onset of the β-catenin-dependent canonical Wnt signaling pathway occurs when the Wnt ligand binds to Frizzled (Frz) and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)5/6 coreceptors. In the absence of Wnt, β-catenin undergoes phosphorylation and is sequestered in the cytoplasm by a complex involving Axin, adenomatous polyposis (APC), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and casein kinase 1 (CK1). Phosphorylated β-catenin then interacts with the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP, leading to ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (Stamos and Weis, 2013; Schaefer and Peifer, 2019; Konsavage et al., 2012). Upon Wnt stimulation, phosphorylation of LRP5/6 induced by Frz activates the scaffold protein Dishevelled (Dvl), which facilitates the recruitment of Axin to the receptors and inhibits β-catenin phosphorylation. The accumulated unphosphorylated β-catenin moves from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and promotes the transcription of Wnt target genes by interacting with T cell-specific factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (LEF) (Zhan et al., 2017; Clevers and Nusse, 2012). In the absence of Wnt stimulation, YAP and TAZ participate in the destruction complex, where they interact with Axin1. This complex acts as a cytoplasmic anchor and functional reservoir for YAP/TAZ. Upon exposure to Wnt ligands or loss of destruction complex components, such as Axin or APC, YAP/TAZ are rapidly released from the complex. This leads to their relocation to the nucleus and subsequent increase in YAP/TAZ/TEAD-dependent transcription. Thus, the activation of Wnt signaling displaces YAP/TAZ from the destruction complex, facilitating their nuclear accumulation and the initiation of target gene expression (Azzolin et al., 2014).

Studies have shown the activation of the Hippo pathway by the Wnt signaling pathway and vice versa, where YAP/TAZ regulate the Wnt pathway by modulating β-catenin activity (Li et al., 2019). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), WNT7A inhibits the adipogenesis of fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs) by inducing the nuclear translocation of YAP independent of β-catenin. Moreover, WNT7A promotes the nuclear retention of YAP and TAZ during FAP differentiation (Fu et al., 2023). Another study using intestinal organoids, showed that the modulation of Wnt signaling, either through Porcupine (Porc) inhibitor LGK974 or Wnt activation in APC homozygous mutants, results in changes in YAP mRNA and protein levels. It was also recognized that Wnt signaling governs the transcriptional control of YAP and TEAD genes. In contrast, the subcellular localization of YAP in intestinal organoids specifically involves Src family kinase signaling independently of Wnt pathways (Guillermin et al., 2021). In colon cancer cells, the levels of β-catenin and YAP proteins increase upon stimulation with WNT3A, implying that YAP may be a downstream target of the Wnt signaling cascade (Park and Jeong, 2015). A study showed earlier that nuclear β-catenin/TCF (T-cell factor) complexes bind to a DNA enhancer element within the first intron of the YAP gene. Consequently, the decrease of YAP mRNA and protein levels in colon cancer cells is attained through the suppression of β-catenin expression (Konsavage et al., 2012). Furthermore, WNT3A has been found to stabilize TAZ by preventing its interaction with 14-3-3 proteins through PP1A. This stabilization brings about the dephosphorylation of TAZ, its migration into the nucleus, and subsequent increase in activity (Byun et al., 2014). Extending on these findings, another group demonstrated that WNT3A and WNT5A/B enhance YAP/TAZ activity, but this activation occurs via an alternative pathway independent of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, through the Wnt-FZD/ROR-Gα12/13-Rho GTPases-LATS1/2 axis (Park et al., 2015). Conversely, some studies have also shown the activation of Wnt signaling pathway by YAP/TAZ. Rosenbluh et al. (2012) and Wang Y. et al. (2017) showed that YAP is required for β-catenin dependent tumorigenicity via regulating its expression level, subcellular localization and transcriptional activity of β-catenin. YAP-overexpressing mice exhibit elevated expression of β-catenin and target genes (Lgr5 and Cyclin D), along with increased proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells compared to wild-type mice. Similarly, YAP knockdown has been shown to reduce β-catenin activation and downstream gene expression in both intestinal and gastric cells (Pan et al., 2017).

The TEAD family of transcription factors is crucial for the downstream genes induced by oncogenic YAP in the nucleus. Likewise, the activation of β-catenin-induced target genes relies on TCF/LEF family factors. Mechanistically, YAP can directly interact with β-catenin in the nucleus, forming a YAP/β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex in cancer cells (Deng et al., 2018). Another investigation has revealed a novel mechanism by which YAP/TAZ regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, distinct from these studies. In this case, the investigators showed that the phosphorylation of YAP at Ser127 decreases the transcriptional activity of β-catenin/TCF and the subsequent gene expression by directly interacting with β-catenin. As a result, the Hippo pathway may inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by impeding the nuclear translocation of β-catenin rather than by regulating its stability (Imajo et al., 2012). The crosstalk between Hippo-YAP/TAZ and β-catenin signaling also occurs during brain development, in neurodegenerative disorders and in glioma pathogenesis (Ouyang et al., 2020; Sileo et al., 2022).

YAP/TAZ and the microenvironmentCells possess remarkable capabilities for physical interaction with adjacent cells and their surroundings. They can perceive and react to mechanical stimuli by translating them into biochemical signals through a process termed mechanotransduction (Saraswathibhatla et al., 2023). The perception of mechanical cues, denoting physical forces applied to cells, is predominantly sensed by transmembrane proteins and the actin cytoskeleton. This regulatory mechanism entails various cellular components such as the cytoskeleton, the nucleoskeleton, integrins, and focal adhesions (FAs). These components trigger a sequence of intracellular processes, such as the activation of signaling pathways, ion channels, and transcriptional regulators (Ritsvall and Albinsson, 2024). Upon detection of force, cells respond by producing opposing forces of equal magnitude through the modulation of myosin motor activity to maintain equilibrium in the actin cytoskeleton (Janmey and Miller, 2011; Parsons et al., 2010). External mechanical forces can induce active modifications in the actin cytoskeleton. For instance, cellular stretching can result in continuous activation of RhoA and myosin, consequently leading to the generation of stress fibers (Torsoni et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2007; Cai and Sheetz, 2009). Several investigations have highlighted the functions of YAP and TAZ as mechanotransducers, exerting a dynamic impact on cellular characteristics like differentiation and the development of diseases (Lin et al., 2024). Initially documented by Dupont et al. (2011), it was proposed that the activation of YAP and TAZ occurs independently of the Hippo pathway in response to diverse mechanical stimuli, such as extracellular matrix stiffness, cellular geometry, and cytoskeletal tension. The authors also showed compelling evidence implying that the state of the F-actin cytoskeleton and the function of Rho GTPase are crucial for the regulation of YAP/TAZ under these conditions. Additionally, it was demonstrated that this regulatory mechanism could operate without the involvement of LATS, representing a non-canonical Hippo signaling pathway as discussed earlier (Dupont et al., 2011).

The extensive variety in cellular geometries reflects the diverse array of cellular morphologies that emerge throughout morphogenesis, remodeling, and planar polarization of tissues and organs. It is widely recognized that alterations in cell geometry can effectively regulate cell proliferation, a process that is monitored by YAP/TAZ in response to such changes (Lindsey et al., 2015; Gibson and Gibson, 2009). A research study replicating this result illustrated that YAP primarily localizes in the cytoplasm of cells occupying a small surface area, whereas it is distinctly concentrated in the nucleus of cells spread over a larger surface area (Wada et al., 2011). Another study showed a substantial change in the intracellular localization of YAP/TAZ proteins between soft and rigid matrices, with most cells showing predominant nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ on rigid matrices and a lesser number displaying distinct nuclear localization on soft matrices in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Liu et al., 2015). A recent study also established that the stiffening of the extracellular matrix triggers aberrant activation of YAP/TAZ and reorganization of the cytoskeleton in Schlemm’s canal cells in the eyes, a process that can be completely reversed through matrix softening in a time-dependent manner (Li et al., 2024).

Mechanosensitive molecules situated in the cellular membrane play a vital role in sensing external mechanical cues, thereby initiating mechanotransduction. These molecular structures include integrins and focal adhesions. Integrins are known to regulate YAP/TAZ via focal adhesion sites which serve as an intermediary and are essential for transmitting such signals (Lin et al., 2024). Integrins respond to various extracellular molecules, such as collagen, laminin, and fibronectin (Humphries et al., 2006). When exposed to a rigid surface or high mechanical tension, integrins are activated and aggregated, causing structural alterations in components of focal adhesions. Consequently, downstream signaling molecules are recruited, initiating the organization of the actin-myosin cytoskeleton (Goldmann, 2012). For instance, in endothelial cells (ECs), signaling pathways mediated by the cell junction protein AmotL2, focal adhesions, and the nuclear lamina are essential for the transcription of YAP. A recent study demonstrated that mechanical forces detected at cell-cell junctions through AmotL2 directly impact global chromatin accessibility and the activity of EZH2, thereby influencing YAP promoter activity (Mannion et al., 2024). Furthermore, the application of mechanical force induces an allosteric effect in the extracellular region of integrin αVβ3, leading to increased levels of integrin αVβ3 and fibronectin. Consequently, focal adhesions aggregate and modulate the function of the actin cytoskeleton via downstream signals like RhoA GTPases, ultimately promoting F-actin assembly and YAP expression (Puklin-Faucher and Sheetz, 2009). A recent study illustrated that vinculin, a crucial protein in focal adhesions, governs the ECM stiffness-dependent localization of YAP/TAZ and enhances its nuclear translocation on rigid substrates. The study also revealed that vinculin does not affect the Hippo pathway since LATS1 levels remained consistent between control cells and cells lacking vinculin. Instead, vinculin interacts with F-actin, influencing its arrangement. In addition, studies using treatment with cytochalasin D, an actin polymerization inhibitor, propose that vinculin-mediated increase of YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and activity is connected to actin structure (Kuroda et al., 2017).

In summary, YAP/TAZ is a key regulator of cellular behavior influenced by the microenvironment, including the cytoskeleton, focal adhesions (FA), and integrins. The cytoskeleton’s dynamics affect YAP activity by transmitting mechanical signals through focal adhesions, where integrins play a critical role in sensing and responding to extracellular matrix stiffness. This interaction influences YAP localization and activity, ultimately impacting cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. In recent years, mechanotransduction and the role of YAP/TAZ in mediating the response of cells to mechanical forces have been an area of intense investigation, especially in cancer cells that respond to mechanical changes in the tumor microenvironment (Piccolo et al., 2023; Panciera et al., 2017; Di et al., 2023). However, much less is known about the transduction of mechanosensitive signals in neurons in response to mechanical changes in the brain extracellular matrix.

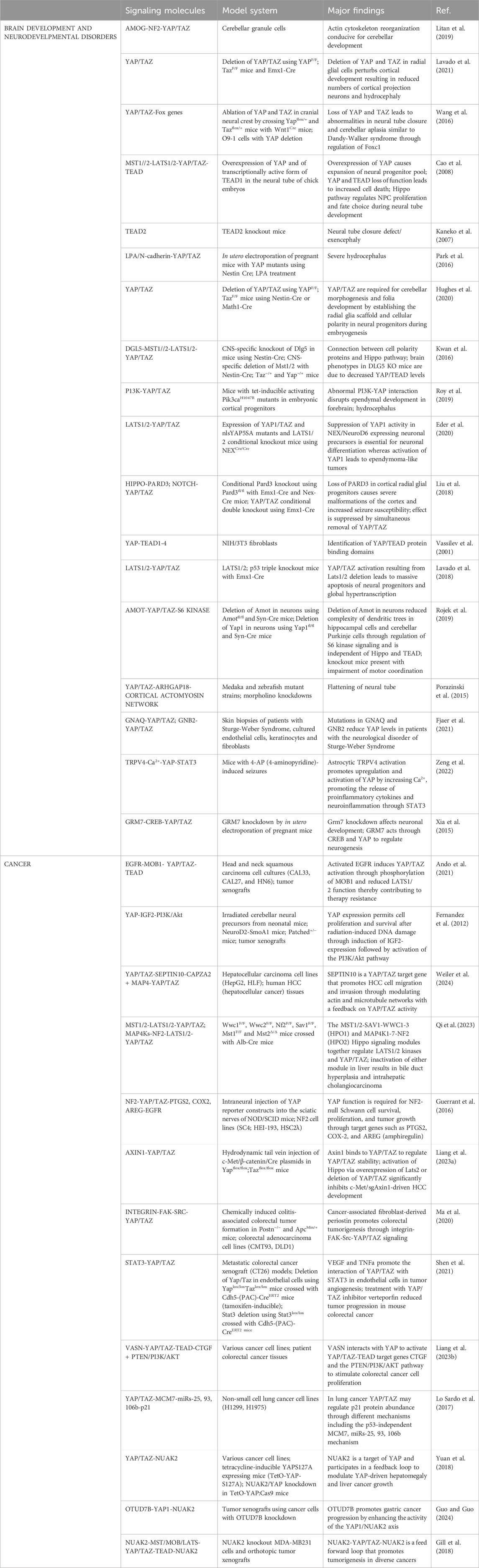

Role of YAP/TAZ in brain developmentThe human brain is the most complex structure known as evidenced by its myriad neuronal and non-neuronal cells and the trillions of cellular connections, enabling the generation of a wide array of cognitive and behavioral responses (Sahu and Mondal, 2021). For the proper development of our intricate nervous system, it is essential to ensure precise spatial and temporal regulation of various signaling pathways. During brain development and maturation, the Hippo pathway has been continuously implicated (Terry and Kim, 2022). Numerous research works have highlighted the involvement of YAP/TAZ in the generation of diverse brain cells. These investigations showcase the ability of this pair to connect numerous biological processes to transcriptional output, serving as an effective mechanism to harmonize multiple cellular and molecular processes during and after development (Terry and Kim, 2022). Mammalian brain development starts with the formation of the neural tube and progresses to the development and refinement of the cortex, cerebellum, cerebrum and ventricular system (Terry and Kim, 2022; Sahu and Mondal, 2021; Lavado et al., 2021). This segment explores the conventional function of YAP/TAZ in the context of brain development (Table 1).

Table 1. Model systems used to evaluate YAP/TAZ signaling cascades in brain development, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cancer.

Brain development initiates from the neural tube which is comprised of actively dividing neuroepithelial cells also recognized as neural progenitor cells (NPCs) that exhibit elevated levels of YAP (Wang et al., 2016; Milewski et al., 2004). The elimination of YAP from WNT1-expressing cells, encompassing cells located in the dorsal region of the neural tube, roof plate, and neural crest, has been demonstrated to lead to abnormalities in neural tube closure (Wang et al., 2016). Also, an earlier study showed that either the activation of YAP/TEAD or the suppression of MST1/2 and LATS1/2 can trigger the upregulation of Ccnd1 (cyclin D1), facilitating the NPC cycle process. Activation of YAP/TEAD can also diminish the expression of neurogenic b-HLH (basic helix-loop-helix) factor NeuroM, impeding NPCs’ differentiation. Conversely, inhibiting YAP/TEAD can instigate apoptosis in NPCs (Cao et al., 2008). It has been shown that the inability of the neural tube to close results in severe congenital malformations like anencephaly and spina bifida, characterized by the protrusion of CNS neural tissue from its usual domain (Avagliano et al., 2019). Evidence substantiating the involvement of YAP in neural tube closure is demonstrated by TEAD2 conditional knockout mice exhibiting exencephaly, denoting brain tissue protrusion beyond the skull due to the failure in achieving anterior neuropore closure (Kaneko et al., 2007). In a recent investigation involving a family with consecutive fetuses displaying anencephaly, mutations in Nuak2, an upstream negative modulator of Hippo signaling, were identified to diminish YAP activity. It was suggested that this reduction in YAP activity could be the underlying cause of anencephaly (Bonnard et al., 2020). Cao et al.’s (Cao et al., 2008) studies on chick embryos have revealed that the regulation of YAP activity is crucial for the normal proliferation of neural progenitors and the prevention of premature differentiation of progenitor cells. The interaction between YAP and TEAD4 promotes the expression of CyclinD1. In this scenario, decreasing YAP levels resulted in elevated cell death and narrowing of the neural tube, whereas increasing YAP levels boosted precursor proliferation but ultimately reduced the quantity of neurons (Cao et al., 2008). Taking into consideration the above data, it can be concluded that YAP plays a key role in normal neural progenitor cells proliferation and differentiation during early brain development stage and its dysregulation can affect neural tube formation.

The significance of YAP in brain development is also apparent in ependymal cells and choroid plexus epithelial cells found in the ventricular system. After the reduction of neural progenitors in the ventricular zone (VG), a stratum of multiciliate ependymal cells develops to sheathe the ventricles. These ciliated cells move cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the ventricular system, which contains various soluble factors that influence NSC (neural stem cell) lineage and cell survival during development (Deng et al., 2023; Nelles and Hazrati, 2022). It is noteworthy that YAP/TAZ are prominently expressed in choroid plexus cells (Park et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2020), which are involved in CSF production. This development begins around embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) in mice and at 6 weeks post-conception in humans (Lun et al., 2015). Despite their significant levels, the functions and developmental roles of YAP/TAZ in the choroid plexus are not well understood and require further research. YAP expression persists in ependymal cells throughout adulthood, and its absence has been linked to structural defects in the ventricular system (Park et al., 2016). In nervous system-specific YAP mutants generated using Nestin-Cre, severe hydrocephalus is a prominent phenotype characterized by CSF accumulation and ventricular enlargement due to disrupted aqueduct integrity (Park et al., 2016). One factor contributing to aqueduct stenosis development is the insufficient presence or developmental failure of ependymal cells, which compromises the aqueduct ventricular wall integrity and obstructs CSF flow. Dysregulated YAP signaling is also associated with hydrocephalus pathogenesis through different causes, such as Dlg5 mutants and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus induced by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) injection. Dlg5 conditional knockout animals (Nestin-Cre) with reduced YAP/TAZ levels exhibit impaired ependymal cell development. This effect was reversed by simultaneous MST1/2 conditional knockout, leading to ependymal cell layer restoration and aqueduct patency (Kwan et al., 2016). In LPA-induced hydrocephalus, YAP reduction by LPA treatment caused detachment of ventricular lining cells, hindering ependymal cell development and resulting in aqueduct stenosis (Park et al., 2016). While LPA reduces YAP levels in neural progenitors and ependymal cell precursors, YAP overexpression before LPA injection can restore junctions and ventricular attachments, highlighting the significant role of YAP loss in LPA-induced cellular disruption. Conversely, YAP hyperactivation can also impact ependymal cell development, with PI3K overactivation in hGfap-Cre mice leading to abnormal positioning and overproduction of radial glia/ependymal cell precursors, associated with abnormal brain folding and enlarged ventricles (Roy et al., 2019). Moreover, YAP hyperactivity induced by LATS1/2 double-conditional knockout or YAP5SA expression through Nex-Cre results in an increased number of ependymal-like cells resembling ependymoma, a tumor of ependymal cells (Eder et al., 2020). Overall, this evidence suggests that the loss of YAP function reduces the number of ependymal cells, while overactivation of YAP leads to an excess of ependymal-like cells. Thus, the essential role of YAP in ependymal cell development is clearly demonstrated.

During cortical neurogenesis, which starts approximately at 7 weeks post-conception and peaks around 27 weeks post-conception in humans, neurons are generated through rapid cell division of neural progenitors, followed by gliogenesis (Silbereis et al., 2016). There are two distinct categories of progenitors present during cortical neurogenesis: multipotent apical neural progenitors and lineage-restricted progenitors situated at the base. The initial neuroepithelial cells transition into elongated apical radial glial (aRG) cells, also called ventricular radial glial (vRG) cells. Then the basal progenitors, specifically neurogenic intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs), divide in the subventricular zone with basal radial glia (bRG) also known as outer radial glia (oRG) dividing in the outer subventricular zone (Savini et al., 2019). Numerous research works have reported elevated levels of YAP in the developing cortices of mice and humans. Upon gene expression analysis of the developing mouse cortex, subsequent separation into distinct cell types reveals a high expression of YAP and TAZ in aRGs (Mukhtar et al., 2020). Investigations on YAP/TAZ double-conditional knockout animals have confirmed the essential role of YAP/TAZ in the generation of cortical neurons (Lavado et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2018). The decline in cortical neuron production due to YAP/TAZ loss is believed to be partially linked to a decrease in the number of aRG. While one study did not detect alterations in aRG density at E14.5 (Liu et al., 2018), Terry and Kim (2022) indicated that deletion of YAP/TAZ reduced the aRG population and the proportion of proliferating aRG at E16.5 by reducing cell cycle reentry and extending the cell cycle. Notably, the decline in proliferating aRG does not lead to an extreme production of IPCs or early born neurons; instead, there is a decrease in the quantity of IPCs, early born neurons, and late-born neurons. This highlights the necessity of YAP/TAZ not only for aRG proliferation but also for the subsequent generation of aRG-derived cells (Terry and Kim, 2022). Studies involving YAP deletion with Nestin-Cre (Park et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016) or Emx1-Cre (Shao et al., 2020) did not observe proliferation defects at E14.5; however, a recent examination with Nestin-Cre at E15.5 showed a decline in cells in mitosis and S-phase, indicating reduced proliferating aRG. The differences in results might be due to the timing of these studies (E14.5 vs. E 15.5) which suggests that changes in the proliferating cell fraction may be noticeable at later time points. Nevertheless, since the number of aRG remained unaltered in YAP single mutants unlike YAP/TAZ double mutants (Lavado et al., 2021), the impact of reduced aRG proliferation on the aRG population remains unclear. The consequences of YAP loss alone on IPC number and neuron production are not definitively elucidated. Like YAP/TAZ double-conditional knockout studies, YAP single conditional knockout with Nestin-Cre displayed a decrease in IPCs, and uniquely reduced the number of late-born neurons, not early born neurons, at P0 (Vassilev et al., 2001). Conversely, no changes in neuronal production were observed at P21 when YAP was exclusively deleted with Emx1-Cre (Shao et al., 2020). These inconsistencies could stem from variations in the Cre lines utilized or the different time points evaluated, given that cortical development is still in progress at P0 (when Nestin-Cre mice were examined) but not at P21 (when Emx1-Cre mice were studied). In gain of function studies, overexpression of unaltered YAP or the expression of mutated YAP constructs resulted in an increase in the aRG population and a decrease in the production of IPCs and neurons, indicating YAP’s role in impeding aRG progression towards a lineage-specific or specialized state. It is worthy of note that activation of YAP has been successfully accomplished by the overexpression of wild-type YAP or by utilizing various YAP mutant constructs that contain sites resistant to LATS1/2 phosphorylation. These sites involve specific amino acid substitutions, such as serine to alanine at positions 127 (1SA), 127 and 381 (2SA), and 61, 109, 127, 164, 381 (5SA), which have been employed in numerous in utero electroporation experiments. The most severe consequence was noted when the YAP5SA mutant structure is expressed, leading to potential cell death (Lavado et al., 2018). The impacts of increased YAP5SA levels are somewhat mitigated by the presence of YAPS94A, which eliminated the interaction between YAP and TEADs, implying that the gene transcription regulated by TEADs contributes to the repercussions of excessive YAP5SA. In a different investigation, cells overexpressing YAP5SA formed clusters proximal to the lateral ventricle and sparked non-cell autonomous gliogenesis (Han et al., 2015). Conversely, in another analysis, the positioning of YAP5SA-expressing cells was altered towards the vicinity of the cortical ventricular (VZ) and cortical subventricular (SVZ) regions (Cappello et al., 2013). These gain-of-function investigations corroborate the notion that maintaining optimal levels of YAP/TAZ is vital for typical cortical development in the brain.

Cerebellar development is characterized by a prolonged duration and results in the generation of the most abundant neurons in the human brain, namely, the cerebellar granule neurons (Cho et al., 2011). This intricate process is highly susceptible to environmental insults during birth, as well as cerebellar injuries resulting from premature birth, often leading to reduced cerebellar size (Steggerda et al., 2009). Recent genetic investigations have unveiled the critical involvement of YAP/TAZ in cerebellar development and the recuperation following early postnatal injuries. A recent study has established a functional association between the Na, K-ATPase β2 subunit/adhesion molecule on glia (AMOG) and the Hippo pathway activator Nf2 (Neurofibromin-2/Merlin) during the differentiation of cerebellar neurons. In cerebellar granule precursor cells, AMOG exerts negative regulation on the expression of Nf2, thereby enhancing YAP activity and facilitating actin cytoskeleton reorganization conducive to cerebellar development (Litan et al., 2019). Further substantiating the expression and function of YAP in cerebellar neurons is evidence indicating that the absence of YAP in neurons results in morphological abnormalities in Purkinje cell dendrites, characterized by reduced dendritic complexity and motor coordination deficiencies. YAP Syn-Cre conditional knockout animals exhibit an increased number of granule neurons within the molecular layer, implying impaired migration in YAP-deficient granule neurons. These findings collectively suggest that YAP displays dynamic expression in various cell types during and after cerebellar development, with its depletion leading to discernible functional deficits. YAP/TAZ double-conditional knockout (Nestin-Cre) animals display diminished cerebellar size (Hughes et al., 2020; Rojek et al., 2019) and a flattened embryonic cerebellar shape, resembling the flattened morphology observed in medaka fish embryos carrying a mutated form of YAP (Porazinski et al., 2015). Despite investigations into the role of YAP/TAZ in granule cell progenitor (GCP) proliferation, conflicting evidence has emerged from studies in cell culture and genetic studies. While YAP overexpression has been linked to increased GCP proliferation in cell culture, YAP knockdown has been associated with decreased GCP proliferation (Rojek et al., 2019; Fernandez et al., 2009). Genetic deletion of YAP in GCPs using Nestin-Cre did not impact the GCP proliferation rate or folia formation. Additionally, YAP/TAZ deletion did not hinder GCP over-proliferation induced by SmoM2, an activated allele of Smoothened (Yuan et al., 2022), indicating that the in vivo function of YAP/TAZ in GCP proliferation may not be essential for normal physiological functioning or in the context of type II medulloblastoma mediated by SHH signaling. It is of interest to note that YAP plays a crucial role in the restoration of cerebellar size and architecture after radiation-induced damage during the early postnatal period. The absence of YAP in these precursor cells within the cerebellum diminished the capacity of the cerebellum to undergo regeneration post irradiation. Despite the normal initial proliferation of regenerated GCPs, the survival of cells was notably compromised in the absence of YAP. Intriguingly, the simultaneous removal of both YAP and TAZ did not impact the recovery of GCPs, despite the necessity of YAP for the survival of regenerated GCPs, indicating a potentially intricate interaction between these two paralogs in the process of regeneration post injury (Yang and Joyner, 2019).

A role for YAP/TAZ in neurodevelopmental disordersNeurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are defined by the inability to attain cognitive, emotional, and motor developmental milestones. Typically, NDDs are linked with the disruption of the intricately synchronized occurrences that facilitate brain maturation. Conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and epilepsy fall within the spectrum of NDDs (Parenti et al., 2020). While research endeavors have sought to establish a connection between the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders and the Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway (Table 1), a direct implication of YAP/TAZ in most neurodevelopmental disorders remains elusive.

Sturge–Weber syndrome is identified as a neurocutaneous disorder distinguished by vascular malformations impacting the skin, eyes, and leptomeninges of the brain, which can give rise to conditions such as glaucoma, seizures, and intellectual disability. Seizures represent an epileptic manifestation of Sturge-Weber syndrome, and the pathological transformations induced by this syndrome contribute to the hyperactivation of the MAPK pathway (Comi, 2015; Fjaer et al., 2021). The gene GNAQ encodes a G-protein α-subunit (Gαq) of heterotrimeric G-proteins, and the mutation associated with Sturge–Weber syndrome manifests as an activating mutation, prompting an elevation in downstream pathways including MAPK and YAP. Interestingly, in patients negative for the GNAQ mutation, a novel somatic mutation in GNB2 was unveiled, encoding a β-subunit of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex. Notably, this mutation presents an alternative molecular groundwork for mutated G-protein signaling in Sturge–Weber syndrome. The expression of mutant and wild-type GNAQ and GNB2 instigated distinct MAPK phosphorylation levels, while inducing analogous alterations in the YAP pathway. This implies that the YAP pathway might hold greater significance in the pathogenesis of Sturge–Weber syndrome compared to the MAPK pathway (Fjaer et al., 2021). Conversely, a study has demonstrated that the absence of partitioning-defective 3 (PARD3) prompts radial glial progenitor cells (RGP) to undergo excessive neurogenesis, ultimately culminating in cortical augmentation and epilepsy. Furthermore, the inhibition of transcriptional co-activators YAP and TAZ within the Hippo pathway curtails excessive neurogenesis in RGP and diminishes seizure frequency, indirectly indicating a plausible association between epilepsy and the Hippo pathway, along with the involvement of YAP/TAZ (Liu et al., 2018).

A recent and different study examined the brains of 4-AP (aminopyridine)-induced mice and noted the activation and upregulation of TRPV4 (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4) in astrocytes, leading to increased [Ca2+] levels, enhanced nuclear translocation of YAP, elevated p-STAT3 levels, and subsequent upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. The surge in A2 astrocytes intensifies neuroinflammation, causing disruptions in the brain’s microenvironment, thereby exacerbating seizure severity and neuronal impairment. Inhibition of TRPV4 chemically rebalanced the intracerebral immune microenvironment in mice, shielding neurons from extensive damage and reducing seizure severity. Additionally, the study implicated YAP in stimulating astrocyte activation and highlighted the involvement of the STAT3 pathway in fostering the release of proinflammatory cytokines in 4-AP-induced mice (Zeng et al., 2022). One more study has established an association between the metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (GRM7) and brain developmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. GRM7 plays a role in neurogenesis by modulating the signaling pathways of CREB and YAP. The regulatory function of GRM7 in the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitors is facilitated by its impact on the phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 and the levels of YAP expression. Depletion of GRM7 function resulted in escalated phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 (active form) and increased expression of YAP (active form). They also observed that the downregulation of GRM7 led to an upregulation in the expression of CyclinD1; a similar outcome was noted with the overexpression of YAP. The rise in the active YAP level resulting from the silencing of GRM7 subsequently triggered the upregulation of CyclinD1, which in turn facilitated the proliferation of NPCs; these occurrences align with the established role of YAP. Together this shows that GRM7 plays a role in regulating neurogenesis, at least in part mediated through YAP (Xia et al., 2015).

YAP/TAZ in cancer developmentAs discussed earlier on, dysregulation of the Hippo pathway is a common occurrence in numerous human tumors, with YAP/TAZ activation being an indispensable hallmark for multiple cancer hallmarks. Within this segment, we discuss the role of the Hippo pathway in different types of human cancer (Table 1). A prominent function of YAP/TAZ in brain cancer is notably evident in high-grade gliomas, where they play a role in the advancement and progression of tumors, correlating with an unfavorable prognosis. Elevated levels of YAP/TAZ mRNA and protein are significantly identified in glioma tissues alongside their target genes, namely cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), CTGF, and baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5) (Zhang H. et al., 2016). A recent investigation unveiled a non-transcriptional regulation of YAP/TAZ signaling in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), pinpointing IMP1 as one of the highly expressed RNA binding proteins (RBPs) in mesenchymal GBM and glioma stem-like cells (GSCs). IMP1’s recognition and binding to m6A-modified YAP mRNA led to its stabilization and translation, consequently activating Hippo signaling. Furthermore, the study established that IMP1 establishes a feedforward loop with YAP/TAZ, thereby fostering GBM/GSC tumorigenesis and malignant advancement (Yang et al., 2023). The improper activation of YAP/TAZ in gliomas can be linked to LATS1/2 downregulation, instigating cancer progression (Zhang H. et al., 2016). Furthermore, chromobox homologue 7 (CBX7), a constituent of polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) known as a YAP/TAZ suppressor, has been observed to be decreased in GBM because of promoter hypermethylation (Nawaz et al., 2016). Furthermore, YAP/TAZ can be stabilized by actin-like 6A (ACTL6A), which experiences upregulation in gliomas. The interaction of ACTL6A with YAP/TAZ disrupts the association with YAP-stem cell factor-beta-transducing repeat-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (YAP-SCF-β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase), thereby impeding YAP protein degradation (Ji et al., 2018).

Medulloblastoma is the most prevalent malignant pediatric brain cancer and originates from the cerebellum. Surprisingly, it is still not clear how YAP/TAZ promotes the development of this cancer, but earlier it was shown that YAP facilitates the acceleration of tumor growth and promotes radio-resistance in medulloblastoma, thereby fostering continuous proliferation following radiation exposure. The functionality of YAP allows cells to progress into mitosis despite DNA damage remaining unrepaired, achieved by inducing the expression of IGF2 and activating Akt, consequently leading to the deactivation of ATM/Chk2 and the circumvention of cell cycle checkpoints (Fernandez et al., 2012). More recently, a study demonstrated that the heightened activation of the hedgehog signaling pathway, which triggers YAP, results in the development of medulloblastoma within cerebellar granule neuron precursors. The nuclear localization of YAP has been observed across all histological subtypes of medulloblastoma, with desmoplastic nodular medulloblastomas displaying the most intense YAP immunopositivity (Ahmed et al., 2017). It remains to be determined whether YAP activation will be more prevalent in the distinct molecular subgroups of these tumors.

One of the cancers in which the role of YAP/TAZ is better defined is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most prevalent primary liver tumor with over 90% of cases (Asafo-Agyei and Samant, 2024). Numerous studies have shown that the dysregulation of Hippo signaling within the liver has the potential to induce significant hepatomegaly promptly, with YAP/TAZ playing an essential role in liver regeneration post-hepatectomy (Driskill and Pan, 2021).

A recent study showed that elevated expression of SEPTIN10 has shown a positive correlation with the dissemination of tumor cells, particularly evident through increased vascular invasion in HCC. SEPTIN10, identified as a direct target gene of YAP/TAZ, facilitates intracellular tension by modulating actin stress fiber formation. Additionally, its depletion has been noted to decrease the expression of established YAP/TAZ target genes at both mRNA and protein levels (Weiler et al., 2024). Frequent reduction of Succinate dehydrogenase enzyme (SDH) in samples obtained from HCC patients is associated with heightened succinate levels and po

留言 (0)