Graphical Abstract.

1 IntroductionChronic inflammation of the colonic and rectal mucosa that recurs is the primary characteristic of ulcerative colitis (UC) (Xia et al., 2024). Over the past decade, UC has emerged as a public health challenge worldwide. In 2023, the prevalence of UC was estimated to be 5 million cases around the world (Le Berre et al., 2023), and the incidence continues to rise rapidly across South America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa (Ng et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the pathogenesis of UC has not been fully elucidated, the development of UC is influenced by a variety of factors, encompassing genetic predisposition, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and environmental factors (Kobayashi et al., 2020). There is growing evidence that UC is an overly robust mucosal immune response to specific gut microbiota dysregulation, characterized by abnormal microbiota composition and bacterial products (Fang et al., 2021). The maintenance of intestinal mucosal homeostasis depends on the balanced coexistence of a diverse commensal microbial ecosystem, when intestinal microbiota imbalance can result in a decline of the pivotal functions of the gut, subsequently elevating the risk of UC onset.

The human digestive system hosts a diverse and intricate microbial community that profoundly impacts disease progression, particularly in maintaining intestinal homeostasis, modulating immune responses, and regulating inflammation (Wang et al., 2020). The healthy adult gut harbors over 100 trillion bacteria, encompassing more than 1,000 species with varying levels of abundance (Lozupone et al., 2012). However, disruptions in the gut microbiota can precipitate various health disorders, including inflammatory and immune-related conditions (Ding et al., 2024). Evidence indicates that fecal transplantation effectively restores microbial equilibrium in the intestine (Zhao et al., 2021). Although the exact mechanisms driving these responses remain unclear, accumulating data implicates intestinal microbiota dysregulation as a significant contributor to UC pathogenesis (Zhu et al., 2022). The intestinal flora was significantly less rich and diverse in UC patients than in healthy control subjects. Previous studies have shown that, compared with healthy people, the intestinal environment of UC patients is characterized by a reduced presence of Firmicutes and an increased prevalence of Bacteroidetes organisms, as well as facultative anaerobes (Hansen et al., 2010). Notably, the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, particularly Escherichia coli and Shigella, correlates with heightened intestinal inflammation. In contrast, there is a concurrent decrease in the representation of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, which are typically more abundant in healthy gut microbiomes (He et al., 2021). Conversely, promoting the growth of Lactobacillus and Akkermansia while suppressing Vibrio erysipelas may alleviate UC symptoms (Ke et al., 2021). The disruption of intestinal microbiota is strongly associated with intestinal inflammation. The immune system of the intestinal mucosa employs multiple mechanisms to protect the host from pathogenic infections and minimize tissue damage arising from innate and adaptive immune responses (Jackson and Theiss, 2020). Insufficient regulation of these immune processes can lead to chronic inflammation (Koboziev et al., 2014). Concurrently, evidence suggests that microbial dysbiosis and pathogenic bacterial overgrowth compromise the intestinal mucosa, weakening its structural integrity (Feng et al., 2020). Research highlights that chitosan ameliorates UC in mice by enhancing intestinal barrier function, increasing beneficial Cyanobacteria and Lactobacilli populations, and restoring microbial balance in the gut (Wang et al., 2019). Similarly, 16S rRNA sequencing demonstrated that eugenolide mitigated UC by repairing epithelial integrity and modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Furthermore, fecal transplantation can alleviate colitis by elevating acetate levels and adjusting the thick-walled bacteria-to-Bacteroidetes ratio (Wang et al., 2020). Kaempferol can modify the gut microbiome by increasing the Firmicutes-to-Bacillus mimicus ratio while reducing Aspergillus abundance in UC mice (Qu et al., 2021). Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of intestinal microbiota regulation as a therapeutic strategy for UC.

At present, there are many strategies for the treatment of UC, encompassing drug therapy, fecal bacteria transplantation, surgical treatment and diet management, which are mainly drug therapy, such as immunosuppressants, corticosteroids and tumor necrosis factor antagonists (Schreiber et al., 2023). While these medications provide symptomatic relief, many patients eventually experience diminished efficacy or adverse effects, imposing significant physical and financial burdens (Kobayashi et al., 2020). This highlights the necessity of expanding therapeutic options for UC. Notably, traditional Chinese medicine has gained clinical recognition for managing chronic conditions like UC due to its significant therapeutic efficacy and minimal side effects (Zhang et al., 2013). Saussurea costus (SC) is a traditional Chinese herbal medicine has been documented to substantially promote the healing of duodenal ulcer and inhibit peptic ulcer in animals. Its bioactive constituents, including alantolactone, dehydrocostunolide lactone, and costunolide, exhibit pronounced anti-inflammatory properties, effectively ameliorating UC symptoms (Cai et al., 2022). Moreover, evidence suggests that costunolide modulates gut microbiota by increasing Firmicutes and Actinobacteria while decreasing Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (Mao et al., 2022), underscoring SC potential as a therapeutic candidate for UC.

In this study, the 16S rRNA gene sequencing technique was employed to analyze alterations in the intestinal microflora of UC mice following treatment and to assess the capacity of SC to mitigate inflammation and restore the integrity of the damaged intestinal mucosa.

2 Materials and methods2.1 AnimalsC57BL/6J mice (6–8 weeks old) were procured from SBF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. [License No. SCXK(Beijing) 2019-0010] and housed under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions at Yunnan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (R-062021115). All housing and experimental protocols adhered to the ethical guidelines established by the Animal Care and Usage Committee at Yunnan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Kunming, China, permission No. SYXK 2017-0005).

2.2 Modeling and groupingIn a controlled environment (20 ± 2°C, 40–60% humidity, 12 hour light/dark cycle), mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions with access to a standard diet and water. After one week of acclimatization, the C57BL/6J mice were randomly allocated into five groups using a random number table: control, model, and three SC treatment groups. Colitis was induced in all groups except the control by administering 3% DSS (160110, MP, USA) for seven days. SC was subsequently administered via gavage at doses of 0.4 g/kg/day, 0.8 g/kg/day, and 1.6 g/kg/day from days 8 to 14.

2.3 Blood biochemical assaySerum analysis was performed using alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (C009-2-1), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (C010-2-1), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (C013-2-1), creatinine (C011-2-1), uric acid (UA) (C012-2-1), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (A020-2-2) assay kits, all sourced from Nanjing Jiancheng, China.

2.4 Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysisThe preparation of SC decoction involved combining SC with water at an 8:1 ratio by volume, followed by boiling three times for 30 minutes each. The resulting filtrates were collected separately in three batches. The specimens were then sent to Shanghai Biotree Biomedical Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for analysis via UHPLC-QTOF-MS.

2.5 Disease activity indexThe disease activity score, used to evaluate UC severity in mice, was derived from measurements of body weight changes, fecal consistency, and occult blood levels. The scoring system included weight loss percentages (0: none; 1: 1%-5%; 2: 5%-10%; 3: 10%-15%; 4: >15%), fecal consistency (0: normal; 2: semi-liquid; 4: liquid), and blood detection (0: negative; 2: positive occult blood; 4: visible blood).

2.6 Hematoxylin-eosin(HE) stainingColons were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours before paraffin embedding. Subsequently, 5-μm-thick colonic tissue sections were prepared and stained with HE (G1120, Solarbio, China) for histological examination. To evaluate the degree of inflammation present in the samples, a histological colitis scoring system was utilized. This scoring system assigns values ranging from 0 to 12, representing the total score derived from individual cumulative assessments of severity, extent, damage, inflammation, and regeneration, each of which is rated on a scale of 0 to 4.

2.7 Real-time PCR assayTotal RNA was isolated from colonic tissues using RNAiso Plus (9109, Takara, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out with a reverse transcription kit (11141ES60, Yeasen, China). RT-PCR was subsequently performed using SYBR® Premix-Ex TagTM (11202ES08, Yeasen, China) combined with specific primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Amplification and detection were conducted on an ABI QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Relative mRNA expression levels of target genes were normalized to β-actin, and quantification was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

2.8 Immunofluorescence assayFollowing the removal of wax from the paraffin sections, colonic tissue samples were treated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, specifically anti-occludin and ZO-1, diluted at 1:1000. After incubation, the sections were rinsed with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20) to prepare for subsequent steps. A fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (A21207, A11034, Invitrogen, USA, 1:1000) was applied for 1 hour. The samples were then washed with PBS, stained with DAPI, and imaged using microscopy.

2.9 Western blotting assayColon tissues were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime, China) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (P0010, Beyotime, China). Proteins, standardized to equal concentrations, were resolved on 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked for one hour in 5% milk-TBST solution and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, including β-Actin (GB11001, Rabbit monoclonal, 1:5000, Servicebio), ZO-1 (21773-1, Rabbit polyclonal, 1:5000, Proteintech), and Occludin (27260-1, Rabbit polyclonal, 1:8000, Proteintech). Following incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, immunoreactivity was visualized using an ECL detection kit (220616-60, Western Bright TM ECL, Advansta). Images were acquired using the i-Bright™ CL1500 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.10 16S rRNA gene sequencingFresh fecal samples were collected for genomic DNA extraction, followed by PCR amplification, product purification, and standardized quantification to ensure consistent amplification efficiency and precision. Library construction was performed, with quality control measures implemented to validate library integrity. Sequencing was conducted using the Illumina 6000 system, employing high-throughput methods to generate raw data. Subsequent base calling converted raw data into original sequences, which were further analyzed for relevant information.

2.11 Statistical analysisResults were derived from three independent, replicated experiments. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 Statistical significance was assessed via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), revealing differences with P < 0.05.

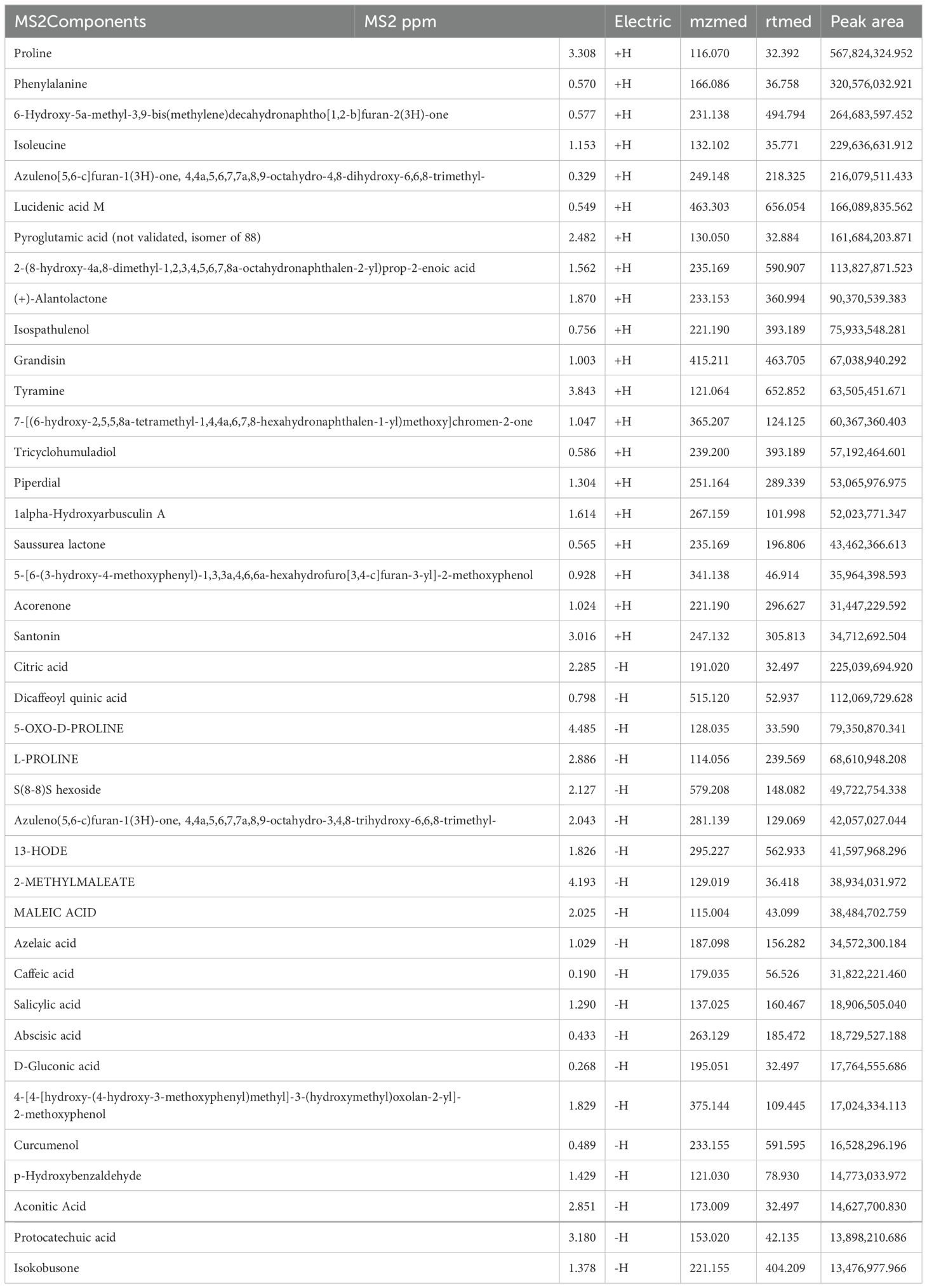

3 Results3.1 Screening active components of SC extract with UHPLC-QTOF-MSThe primary constituents of SC were analyzed using UHPLC-QTOF-MS in both positive and negative modes, a total of 291 components were obtained. Among them, the top 20 substances in each mode ranked by peak area (Table 1) were emphasized as potential candidates for alleviating UC.

Table 1. Identification of components of SC extract by UHPLC-QTOF-MS analysis.

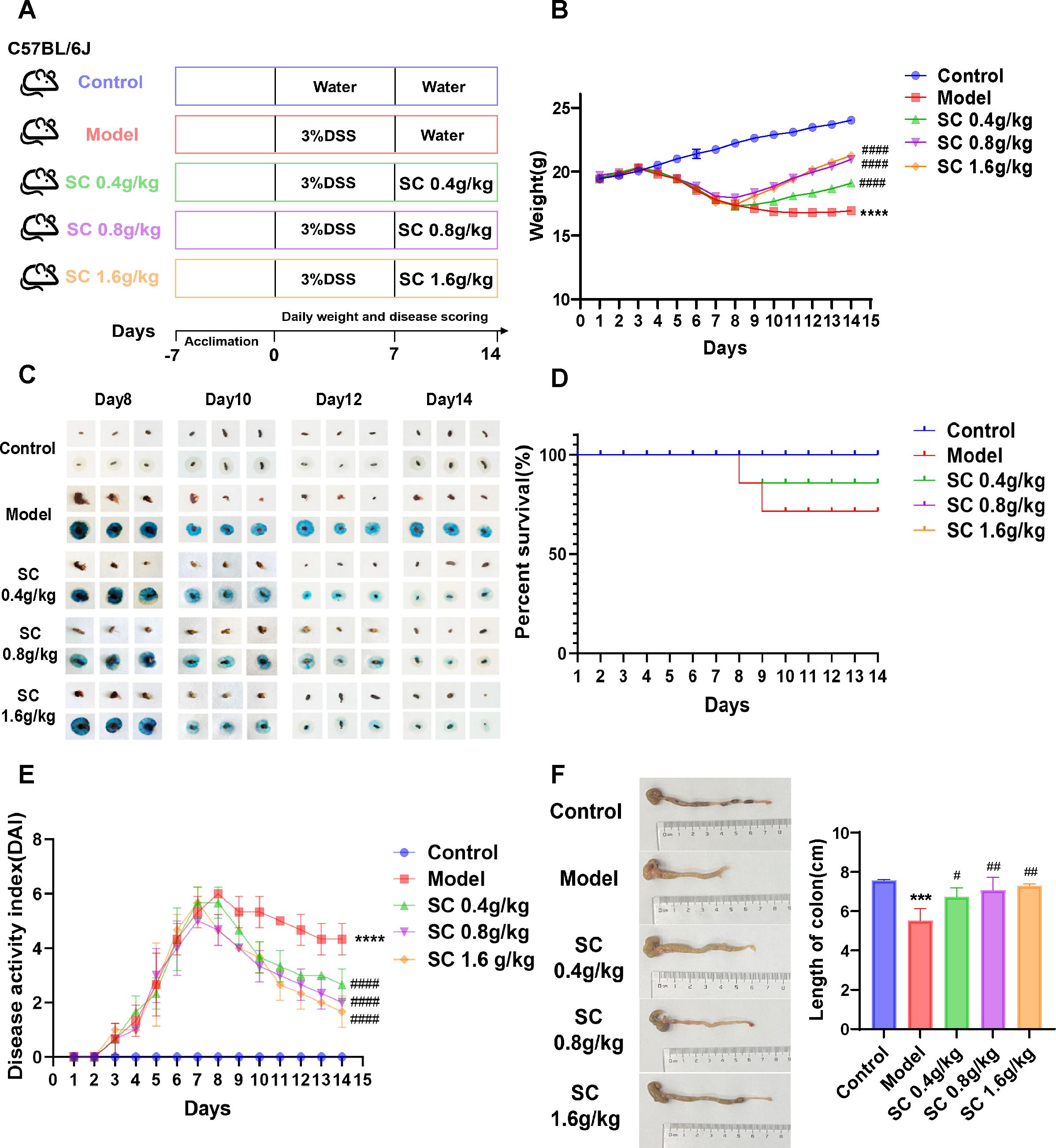

3.2 Treatment with SC alleviates UCTo assess the therapeutic efficacy of SC in colitis, DSS-induced mouse model of colitis was developed, and SC was administered orally at different doses (Figure 1A). Body weight and fecal occult blood were monitored throughout the experiment, revealing that SC treatment significantly mitigated body weight loss (Figure 1B) and reduced fecal occult blood levels (Figure 1C) in colitis mice. Notably, the survival rate of mice receiving a high dose of SC was significantly lower than that of the other groups (Figure 1D). The DAI score, calculated based on fecal occult blood, stool consistency, and weight loss, demonstrated substantial improvement across all SC-treated groups, with the high-dose group showing the greatest therapeutic benefit (Figure 1E). Additionally, SC administration at different doses resulted in a marked increase in colon length compared to the model group (Figure 1F). Collectively, the findings indicate that SC effectively alleviates UC symptoms.

Figure 1. SC significantly improved the disease characteristics of UC mice. (A) The design of experiments in mice; (B) weight changes; (C) Fecal occult blood; (D) Survival rate of mice; (E) DAI scores; (F) Colonic length. (n=3 per group, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. control; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ####P < 0.0001 vs. model).

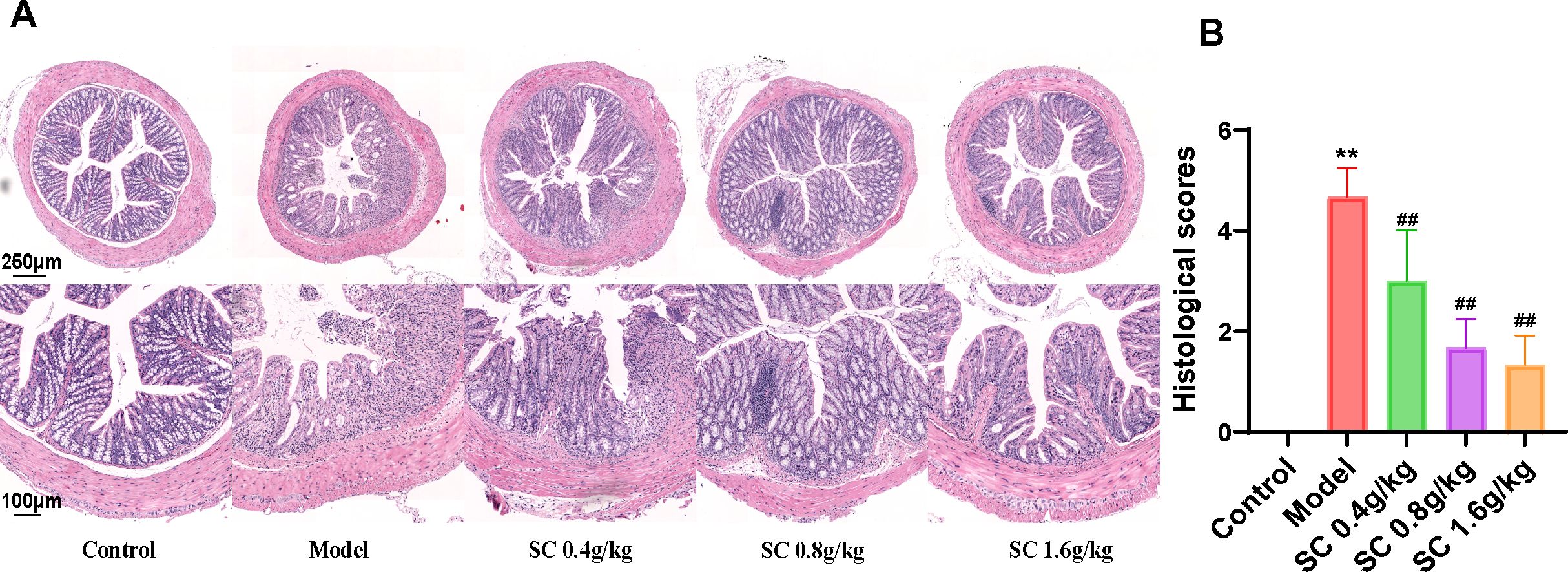

3.3 SC improves histological morphology of the UCThe protective effects of SC on intestinal barrier integrity were assessed by analyzing histological damage in the mouse colon using HE staining. DSS-induced mice exhibited substantial inflammation and tissue injury, characterized by irregular and disrupted colonic crypt structures, loss of goblet cells, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and elevated pathological scores. Treatment with SC at different doses markedly alleviated these abnormalities, with medium and high doses demonstrating the most significant improvements (Figures 2A, B).

Figure 2. SC restored pathological damage of colon tissue. (A) HE-stained sections of the distal colon of differently treated mice; (B) histological scores. (n=3 per group, **P < 0.01 vs. control; ##P < 0.01 vs. model).

Based on the above findings, suggesting that SC has a potential therapeutic effect on UC, we then explored the toxicity characteristics of high-dose SC, serum biochemical tests indicated no apparent liver and kidney toxicity in the SC-treated mice (Supplementary Figures S1A–F). These findings indicate that SC appears to be safe in colitis mice.

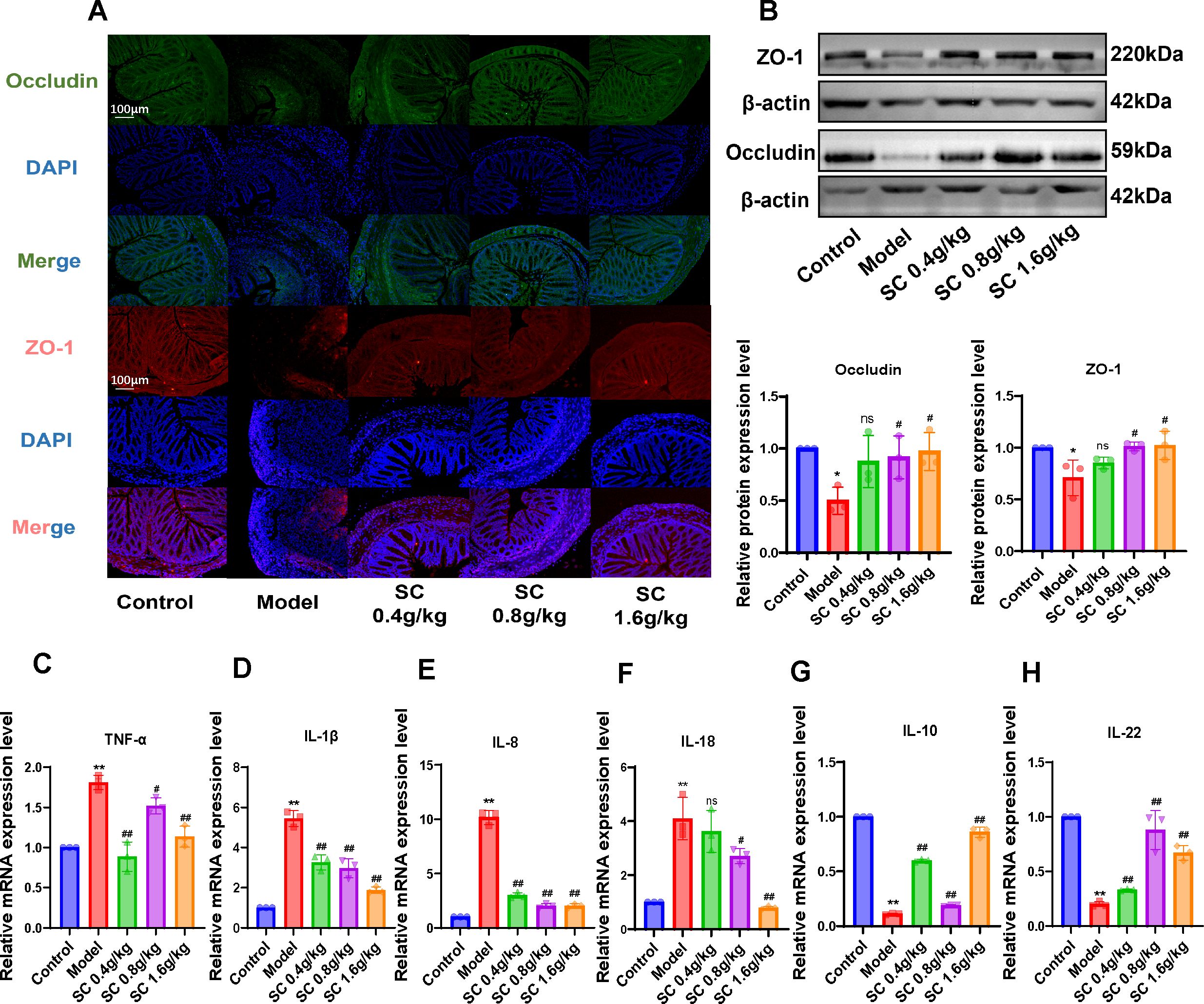

3.4 SC repairs the intestinal barrier and weakens the inflammatory damage of UCTo investigate the effects of SC on intestinal barrier dysfunction and inflammation in colitis mice, tight junction proteins ZO-1 and Occludin in colonic tissues were analyzed using immunofluorescence. The model group exhibited a marked reduction in ZO-1 and Occludin expression, while SC administration at different doses significantly restored their levels in colonic tissues (Figure 3A). Consistent results were confirmed through western blot analysis, demonstrating that SC reversed the downregulation of ZO-1 and Occludin proteins expression in colitis mice (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. The administration of SC can enhance the restoration of the intestinal barrier and suppress the inflammatory response. (A) The expression of intestinal barrier related ZO-1 and Occludin were detected by immunofluorescence. (B) The expression of intestinal barrier related ZO-1 and Occludin were detected by western blot. (C–H) The relative mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-18, IL-10, and IL-22 in colon tissue of mice were detected by RT-PCR. (n=3 per group, ns, nonsignificant *P < 0.05**P < 0.01 vs. control; #P < 0.05##P < 0.01 vs. model).

Additionally, inflammatory markers in colonic tissues were evaluated, revealing increased mRNA expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8 and IL-18, alongside decreased IL-10 and IL-22 levels in the model group. SC treatment significantly alleviated inflammatory responses in colonic tissues (Figures 3C-H). These results indicate that SC may ameliorate UC by restoring intestinal barrier integrity and suppressing inflammation.

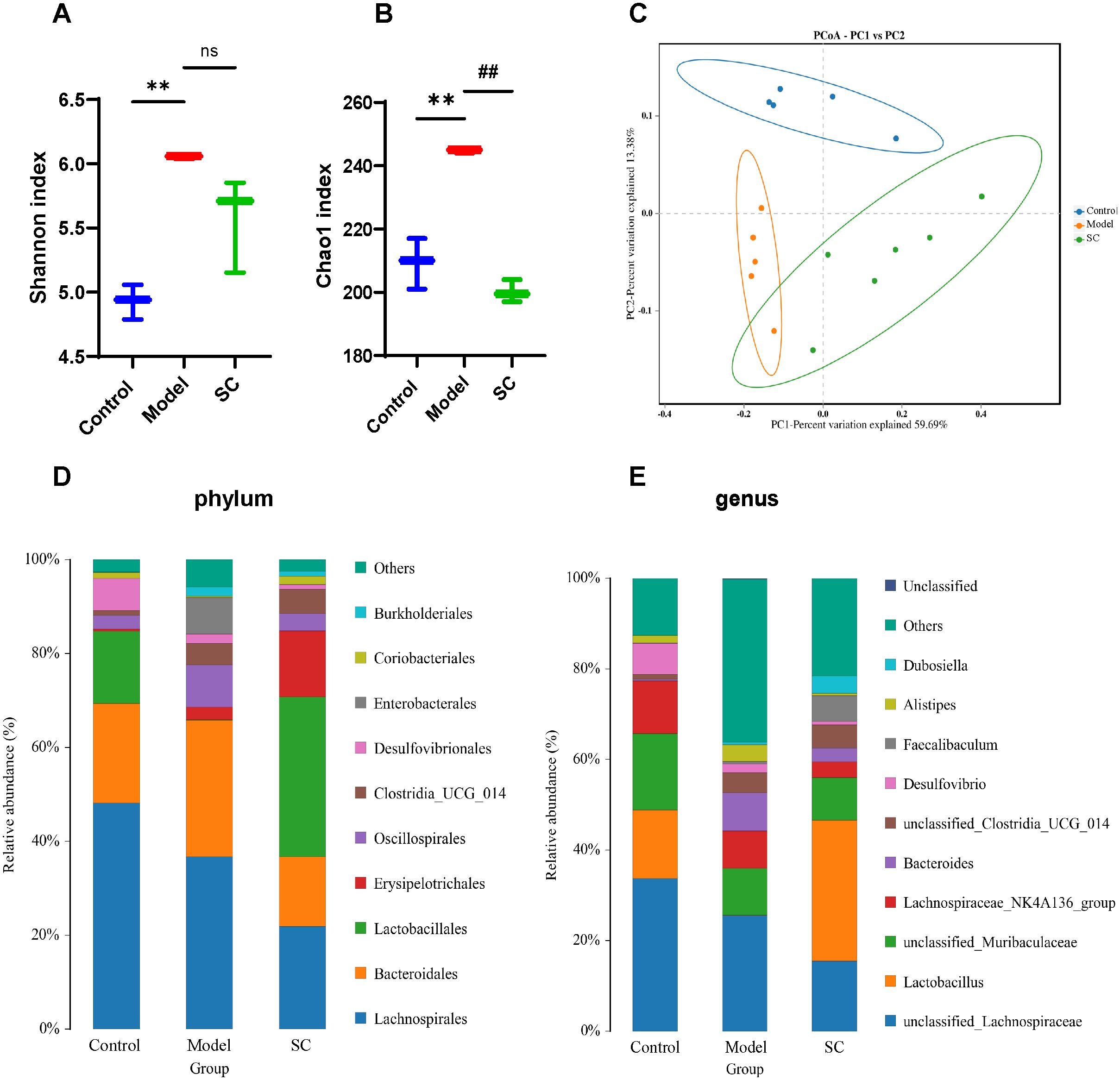

3.5 SC modulates the gut microbiota in UCTo further assess whether SC regulates intestinal microbiota in UC, we used 16s rRNA gene sequencing to analyze intestinal microbiota in colorectum contents. The Shannon and Chao1 indices were employed to characterize the alpha-diversity, thereby assessing species richness and evenness. The Shannon and Chao1 indices were significantly elevated in the DSS-induced model group, whereas SC-treated mice showed a decreasing trend (Figures 4A, B). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) is employed to measures beta-diversity and evaluate the differences or similarities among microbiota communities. The PCoA score plot demonstrated that the three groups exhibited significant distinctions in their microbiota community structures (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. SC modulates gut microbiota in UC. (A) Shannon index; (B) Chao 1 index; (C) Principal component analysis (D) The proportions of the phylum; (E) The proportions of the genus; (n=5 per group, ns, nonsignificant **P < 0.01 vs. control; ##P < 0.01 vs. model.

Next, we observed the bacteria in phylum and genus levels among the control group, model group, and SC group. At the phylum level, the predominant bacterial phylum in the gut microbiota were Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. The findings indicated a rising in Proteobacteria, alongside a decline in Firmicutes observed in mice with UC. After the intervention with SC, a decrease in the levels of Proteobacteria was noted, paired with an increase in Firmicutes (Figure 4D), at the genera level, the colorectal microbiota was dominated by unclassified_Lachnospiracease, unclassified_Muribaculaceae, Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136, Baceroides. In contrast to the control group, the DSS group displayed an increased proportion of Bacteroides, Alistipes, and several other species within their microbiota. In contrast, a reduction in the relative abundance of Lactobacillus was observed. Following treatment with SC, there was an increase in the relative abundance of Lactobacillus, unclassified_Clostridia_UGG_014, Faecalibaculum, and Dubosiella, while Bacteroides and Alistipes showed a decreased relative abundance (Figure 4E).

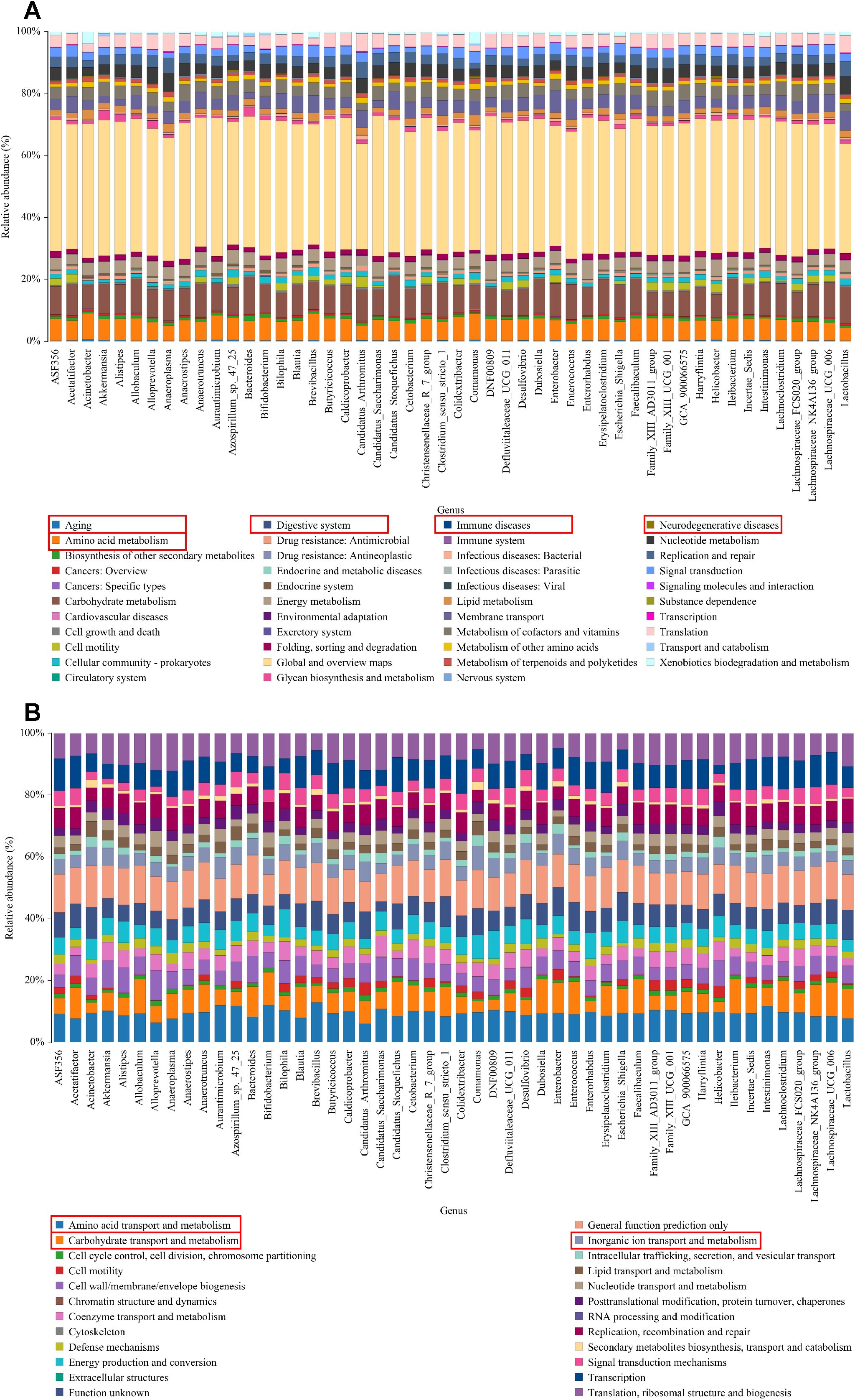

3.6 KEGG/COG annotation analysisKEGG pathway analysis revealed significant variations in functional genes within microbial communities associated with metabolic pathways. Concurrently, COG functional prediction identified the distribution and abundance of sequences within the sample. KEGG metabolic pathway analysis showed that the regulation of intestinal microbiota in UC mice may be closely related to aging, digestive system diseases, immune diseases, neurodegenerative disease and amino acid metabolism (Figure 5A). COG function prediction analysis suggested that the intestinal microbiota function of UC mice was closely related to amino acid transport metabolism, carbohydrate transport and metabolism and inorganic ion transport and metabolism (Figure 5B). These results propose novel perspectives for investigating the role of SC in alleviating UC, warranting further study.

Figure 5. KEGG/COG analysis. (A) The KEGG enrichment analysis of the genus; (B) The COG function prediction analysis of the genus.

4 DiscussionInflammation is a persistent characteristic observed in UC, which is classified as a chronic inflammatory bowel condition. Substantial evidence indicates elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in both UC patients and DSS-induced UC mice (Shao et al., 2024). Traditional Chinese medicine has garnered attention for its anti-inflammatory properties, with Saussurea, first documented in Shennong’s Herbal Classics as a treatment for diarrhea and dysentery, emerging as a focus of interest. SC, native to Yunnan Province and recognized as a geo-authentic crude drug, contains bioactive compounds such as terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, which exhibit potent pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and anti-ulcer activities (Elnour and Abdurahman, 2024). Some studies indicate that the costunolide, the main active component of the terpenoids of saussurea, targets NLRP3 to inhibit inflammasome activation in inflammatory diseases (Xu et al., 2023). Additionally, costiolactone can mitigate DSS-induced colitis by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ, which may be related to the NF-κB, STAT1/3 and Akt signaling pathways (Xie et al., 2020) and costunolide also can restore Th17/Treg balance in colons, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen, further diminishing pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in colitis mice (Lv et al., 2021). Among Saussurea’s active components, sesquiterpene lactone has also demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects in alleviating colitis. This mechanism may involve co-regulation of the MAPK and Nrf2/Hmox-1 signaling pathways[22b]. In our study, SC significantly reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-18 levels in UC mice, reinforcing its anti-inflammatory potential against DSS-induced colitis.

Repairing intestinal barrier damage is recognized as a fundamental strategy in managing UC (Mansouri et al., 2025). Tight junctions, essential structures connecting intestinal epithelial cells, maintain intercellular sealing under physiological conditions, preventing the translocation of pathogenic microorganisms, antigens, and luminal substances into the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa. However, Disruption of these tight junctions allows harmful entities to penetrate the lamina propria, thereby triggering severe inflammatory responses and aggravating colitis progression (Matar et al., 2024). Therefore, regulating the gut microbiota may be the key to alleviating UC. The imbalance of gut microbes may be proportional to the progression of UC. Studies on DSS-induced colitis in mice have demonstrated a marked reduction in beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillaceae and Lachnospiraceae, accompanied by intense inflammatory responses (Li et al., 2024). A human cohort data indicated a decrease in bacterial fucosylation levels among IBD patients, correlating with intestinal inflammation, and reveal that mice with deficient Bacteroides exhibiting lower surface fucosylation are more susceptible to colitis (Lei et al., 2024). Furthermore, Lactobacillus has been shown to elevate IL-10 levels by modulating the development and maturation of regulatory T cells in colitis (Wu et al., 2022). Collectively, the evidence highlights a significant relationship between gut microbiota and colitis pathogenesis.

In addition, intestinal microbes are integral to intestinal barrier repair processes. Studies revealed that walnut peptides restored microbial balance by reducing harmful bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori and Bacteroides, while promoting beneficial bacteria, including Candidatus_Saccharimonas. Mechanistic insights have highlighted their anti-inflammatory properties and barrier-repair capabilities, showing that Bacteroides and Oscillospiraceae_UCG-005 negatively correlate with pro-inflammatory factors (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α) and positively correlate with anti-inflammatory factors and barrier-associated proteins (ZO-1, and Occludin) (Hong et al., 2023). Furthermore, Lactobacillus, a dominant beneficial genus, has demonstrated efficacy in restoring intestinal barrier function, potentially by suppressing Bacteroides and Erysipelatoclostridium, thereby normalizing gut microbiota composition (Zhao et al., 2024). Recently, the regulation of intestinal microbiota through traditional Chinese medicine has attracted increasing interest. Rosavin selectively modulated gut microbiota by reversing DSS-induced microbial dysbiosis and increasing beneficial microbes such as Lactobacillus and Akkermansia (Wang et al., 2024). Huangqin decoction enhanced the prevalence of Lactobacillus and Firmicutes, while significantly reducing Treponema and Bacteroides populations (Zheng et al., 2022). The Xianglian pills, a traditional formulation combining Saussurea and Coptis, regulated microbial succinate production and repaired intestinal barrier damage, effectively mitigating UC symptoms (Liu et al., 2023). A comparable effect was observed with the Xianglian Zhixie Tablet, another classical prescription incorporating Saussurea, which promoted MUC-2, Occludin, and ZO-1 expression to restore intestinal barrier integrity. This mechanism involved boosting beneficial bacterial populations while reducing harmful microbial adherence in the gut (Li et al., 2023). Collectively, these studies highlight the therapeutic potential of Saussurea in modulating gut microbiota and promoting intestinal barrier repair.

Focusing on the role of intestinal microbiota, the study investigated the mechanism by which SC alleviated UC and its association with microbiota modulation in UC mice. SC treatment significantly reduced Proteobacteria and Bacteroides populations while promoting the growth of lactic acid bacteria, consistent with previous research and providing robust evidence for this therapeutic strategy. Notably, the ability of SC to regulate gut microbiota appeared closely linked to gastrointestinal, endocrine, and immune system disorders, as well as aging, amino acid metabolism, and cardiovascular conditions. Furthermore, SC impact may extend to pathways involving amino acid transport, synthesis of cellular structures such as walls and membranes, coenzyme transport, and signal transduction mechanisms.

5 ConclusionsIn conclusion, our study demonstrates that SC effectively mitigates DSS-induced UC symptoms, suppresses intestinal inflammation, strengthens intestinal barrier function, and modulates gut microbiota composition. The findings highlight the potential of SC as a therapeutic strategy for managing UC.

Data availability statementThe datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA1185471.

Ethics statementThe animal study was approved by Ethics Review Committee for animal Experiments, Yunnan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributionsWP: Conceptualization, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft. TL: Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft. YW: Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. LS: Resources, Writing – original draft. LL: Software, Writing – original draft. XL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YQ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82360017). We also received a grant from Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department (202101AZ070001-012, 202201AS070084, 202301AZ070001-4, YNWR- QNBJ-2019-069, 202403AC100007, 202407AB110020) and Scientific Research Fund project of Education Department of Yunnan Province (2024Y370).

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the support provided by the Zhu Zhaoyun Academician Workstation in Yunnan Province, and the graphical abstract created in BioRender. Wu,Y.(2025) https://BioRender.com/z50m027.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1528578/full#supplementary-material

ReferencesCai, X., Yang, C., Qin, G., Zhang, M., Bi, Y., Qiu, X., et al. (2022). Antimicrobial effects and active compounds of the root of aucklandia lappa decne (Radix aucklandiae). Front. Chem. 10, 872480. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.872480

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ding, G., Yang, X., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Du, Y., Wang, M., et al. (2024). Gut microbiota regulates gut homeostasis, mucosal immunity and influences immune-related diseases. Mol. Cell Biochem. doi: 10.1007/s11010-024-05077-y

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Elnour, A. A. M., Abdurahman, N. H. (2024). Current and potential future biological uses of Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 10, e37790. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37790

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Fang, J., Wang, H., Zhou, Y., Zhang, H., Zhou, H., Zhang, X. (2021). Slimy partners: the mucus barrier and gut microbiome in ulcerative colitis. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 772–787. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00617-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Feng, W., Liu, J., Tan, Y., Ao, H., Wang, J., Peng, C. (2020). Polysaccharides from Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. Ameliorate ulcerative colitis via extensive modification of gut microbiota and host metabolism. Food Res. Int. 138, 109777. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109777

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hansen, J., Gulati, A., Sartor, R. B. (2010). The role of mucosal immunity and host genetics in defining intestinal commensal bacteria. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 26, 564–571. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833f1195

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

He, X. X., Li, Y. H., Yan, P. G., Meng, X. C., Chen, C. Y., Li, K. M., et al. (2021). Relationship between clinical features and intestinal microbiota in Chinese patients with ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 4722–4737. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4722

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hong, Z., Shi, C., Hu, X., Chen, J., Li, T., Zhang, L., et al. (2023). Walnut protein peptides ameliorate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis damage in mice: an in silico analysis and in vivo investigation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 15604–15619. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04220

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ke, H., Li, F., Deng, W., Li, Z., Wang, S., Lv, P., et al. (2021). Metformin exerts anti-inflammatory and mucus barrier protective effects by enriching akkermansia muciniphila in mice with ulcerative colitis. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 726707. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.726707

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kobayashi, T., Siegmund, B., Le Berre, C., Wei, S. C., Ferrante, M., Shen, B., et al. (2020). Ulcerative colitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 6, 74. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0205-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Koboziev, I., Reinoso Webb, C., Furr, K. L., Grisham, M. B. (2014). Role of the enteric microbiota in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 68, 122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lei, C., Luo, C., Xu, Z., Ding, S., Sriwastva, M. K., Dryden, G., et al. (2024). Bacterial and host fucosylation maintain IgA homeostasis to limit intestinal inflammation in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 126–143 doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01873-w

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, T., Hu, G., Fu, S., Qin, D., Song, Z. (2024). Phillyrin ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice via modulating the gut microbiota and inhibiting the NF-κB/MLCK pathway. Microbiol. Spectr., e0200624. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02006-24

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, Y., Wang, T., Ma, B., Yu, S., Pei, H., Tian, S., et al. (2023). Xianglian zhixie tablet antagonizes dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis by attenuating systemic inflammation and modulating gut microbiota. J. Inflammation Res. 16, 4331–4346. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S423240

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, C. S., Hu, Y. X., Luo, Z. Y., Qiu, C. W., Deng, X. H., Chen, F. L. (2023). Xianglian pill modulates gut microbial production of succinate and induces regulatory T cells to alleviate ulcerative colitis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 303, 116007. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.116007

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K., Knight, R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lv, Q., Xing, Y., Dong, D., Hu, Y., Chen, Q., Zhai, L., et al. (2021). Costunolide ameliorates colitis via specific inhibition of HIF1α/glycolysis-mediated Th17 differentiation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 97, 107688. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107688

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Mansouri, P., Mansouri, P., Behmard, E., Najafipour, S., Kouhpayeh, A., Farjadfar, A. (2025). Novel targets for mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 144, 113544. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113544

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Mao, J., Zhan, H., Meng, F., Wang, G., Huang, D., Liao, Z., et al. (2022). Costunolide protects against alcohol-induced liver injury by regulating gut microbiota, oxidative stress and attenuating inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Phytother. Res. 36, 1268–1283. doi: 10.1002/ptr.v36.3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Matar, A., Damianos, J. A., Jencks, K. J., Camilleri, M. (2024). Intestinal barrier impairment, preservation, and repair: an update. Nutrients 16, 3494. doi: 10.3390/nu16203494

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ng, S. C., Shi, H. Y., Hamidi, N., Underwood, F. E., Tang, W., Benchimol, E. I., et al. (2017). Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 390, 2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Qu, Y., Li, X., Xu, F., Zhao, S., Wu, X., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Kaempferol alleviates murine experimental colitis by restoring gut microbiota and inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB axis. Front. Immunol. 12, 679897. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.679897

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Schreiber, S., Feagan, B. G., Peyrin-Biroulet, L., Vermeire, S., Faes, M., Harris, K., et al. (2023). Filgotinib improved health-related quality of life and led to comprehensive disease control in individuals with ulcerative colitis: data from the SELECTION trial. J. Crohns Colitis. 17, 863–875. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad018

留言 (0)