Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) characterized by the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury, and is caused by overactivation of the alternative complement pathway (1). Complement component 3 (C3) deficiency causes susceptibility to infections, whereas gain-of-function (GOF) variant in the C3 gene causes susceptibility to aHUS (2). While aHUS can be triggered by various factors, there have been increasing reports of aHUS triggered by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in recent years (3, 4). In this report, we present a 13-year-old boy who developed TMA following COVID-19 infection, and was eventually diagnosed with aHUS with a C3 variant. This case highlights the potential of COVID-19 to trigger aHUS, particularly in individuals with underlying genetic predispositions.

Case presentationA 13-year-old Japanese boy with an unremarkable past medical history developed headache, malaise, and sore throat 2 days before presentation. The next day, he developed a cough, diarrhea, and gross hematuria. Upon visiting his local doctor, he was found to be positive for COVID-19 by rapid antigen test. He was noted to have thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 19 × 109/L. He was referred to a regional hospital the following day, where his laboratory results showed a further decline in platelet count (4 × 109/L) and signs of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. The creatinine level was 1.03 mg/dl, slightly elevated from his baseline creatinine levels (0.8–0.9 mg/dl). He was suspected of having TMA and was transferred to our hospital for further evaluation and management.

Upon admission to our hospital, his body temperature was 36.6°C, blood pressure was 120/69 mmHg, heart rate was 60 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 69 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. He was fully conscious and well oriented. Physical examination was unremarkable, except for petechiae on the bilateral upper extremities. Notable results of initial laboratory analysis included unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (T-Bil 5.7 mg/dl, D-Bil 0.2 mg/dl), elevated LDH (3,074 U/L), AST (137 U/L), BUN (32.6 mg/dl), creatinine (1.13 mg/dl), D-dimer (64.1 µg/ml), and CRP (2.41 mg/dl) levels, mild anemia with hemoglobin 10.5 g/dl, markedly decreased haptoglobin level (< 10 mg/dl), 4% schistocytes on the peripheral blood smear, severe thrombocytopenia (6 × 109/L), and hematuria. ADAMTS13 activity was 85% of the normal control level. Complement analysis revealed normal CH50 and C4 levels, with a slightly decreased C3 level (70 mg/dl). A stool culture was negative for Shiga toxin-producing strains of Escherichia coli in the absence of prior antibiotic administration. Notably, the patient's father had a history of unexplained TMA following influenza infection that required plasma exchange for recovery when he was 36 years old, as well as an instance of gross hematuria following fever at the age of 16 years, the cause of which was not identified.

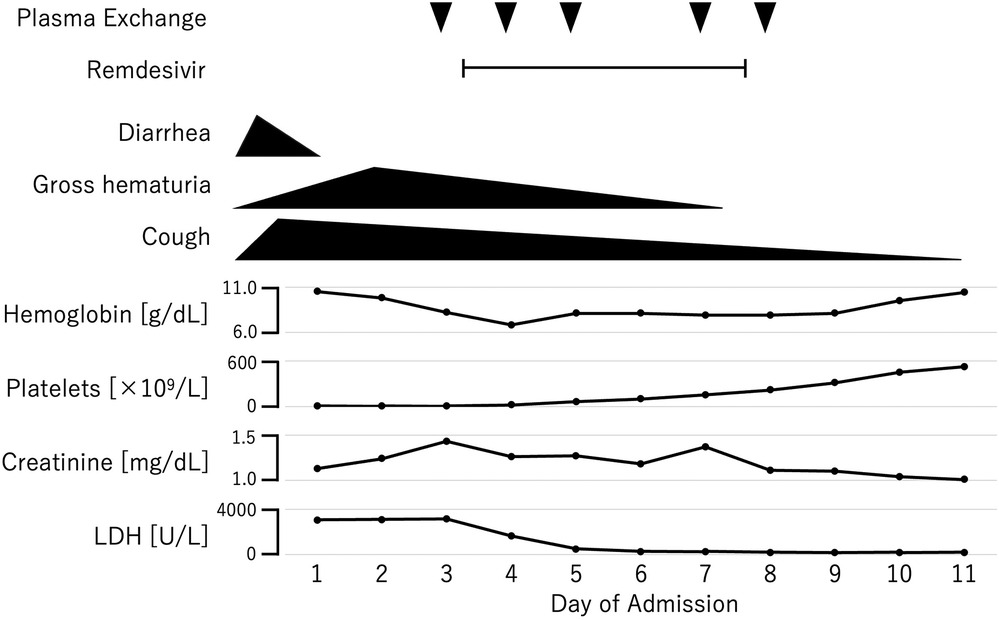

By the third day of hospitalization, the anemia and thrombocytopenia had worsened, and the creatinine level rose to 1.43 mg/dl (Figure 1). At that point, the ADAMTS13 activity result had not yet been received, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) could not yet be excluded. Given the clinical presentation, both aHUS and TTP were still suspected. Consequently, plasma exchange therapy was initiated as a treatment for TMA, which could address both conditions. Plasma exchange was expected to be beneficial in the case of aHUS by removing abnormal complement system proteins and replenishing normal ones. In cases of anti-factor H antibody-associated aHUS, plasma exchange would also help remove anti-factor H antibodies. We excluded TTP after finding that the ADAMTS13 activity, which was obtained from a blood sample collected before the initiation of plasma exchange therapy, was not decreased. Because the platelet count and hemoglobin and creatinine levels were all improving, we did not start anti-C5 antibody therapy, and discontinued plasma exchange after five sessions. We intended to add anti-C5 antibody therapy if the patient's improvement was insufficient. Fortunately, the patient made a full recovery and was discharged on his 18th day in hospital. During the one year after discharge, he remained relapse free, despite having had influenza A once during that period.

Figure 1. Clinical course of the patient.

The diagnosis of aHUS was confirmed by genetic analysis, which revealed a known pathogenic heterozygous C3 GOF variant [NM_000064.4:c.3470T>C (p.Ile1157Thr)]. Anti-factor H autoantibody was negative in a plasma sample collected before the initiation of plasma exchange.

Genetic analysis of the patient's father revealed the same C3 variant, suggesting that the unexplained TMA that the father had experienced was also aHUS.

DiscussionCases of TMA following COVID-19 have been increasingly reported (3, 4). In children, aHUS is the most commonly reported type of TMA, with 16 cases reported (Table 1). Only one patient presented with severe respiratory symptoms. Anti-factor H antibodies were identified in 5 cases. The majority of patients showed decreased C3 level and increased soluble C5b-9 level. Our patient also showed slightly decreased C3 level, but we could not measure the soluble C5b-9 level due to resource limitations. Most patients responded well to plasma exchange and/or anti-C5 therapy, but one patient required renal transplantation, and another patient required continued dialysis. TTP, though a rare cause of TMA in children, has also been observed in a small number of cases following COVID-19 infection (15, 16).

Table 1. Pediatric cases of aHUS following COVID-19.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a hyper-inflammatory disorder occurring 2–6 weeks after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. It consists of persisting fever, involvement of two or more organ systems, clinical severity requiring hospitalization, and laboratory evidence of inflammation. It has been reported that 20% of patients with MIS-C develop acute kidney injury (AKI) (17). MIS-C may also present with variable degree of hematuria (18). MIS-C should be included in the differential diagnosis when AKI or hematuria is present following COVID-19. Generalic ´ et al. reported a case of MIS-C that presented with hematuria and suggested that hematuria may be an early sign of MIS-C (19). Hematuria can be an early symptom in both MIS-C and TMA, making it an important sign that could prompt consideration of these conditions. When hematuria is observed following COVID-19, distinguishing between MIS-C and TMA becomes a critical diagnostic challenge. Findings suggestive of intravascular hemolysis (e.g., decreased haptoglobin) and schistocytes on the peripheral blood smear can help distinguish TMA, such as aHUS or TTP, from MIS-C. The distinction between these conditions is critical, as the management strategies differ significantly.

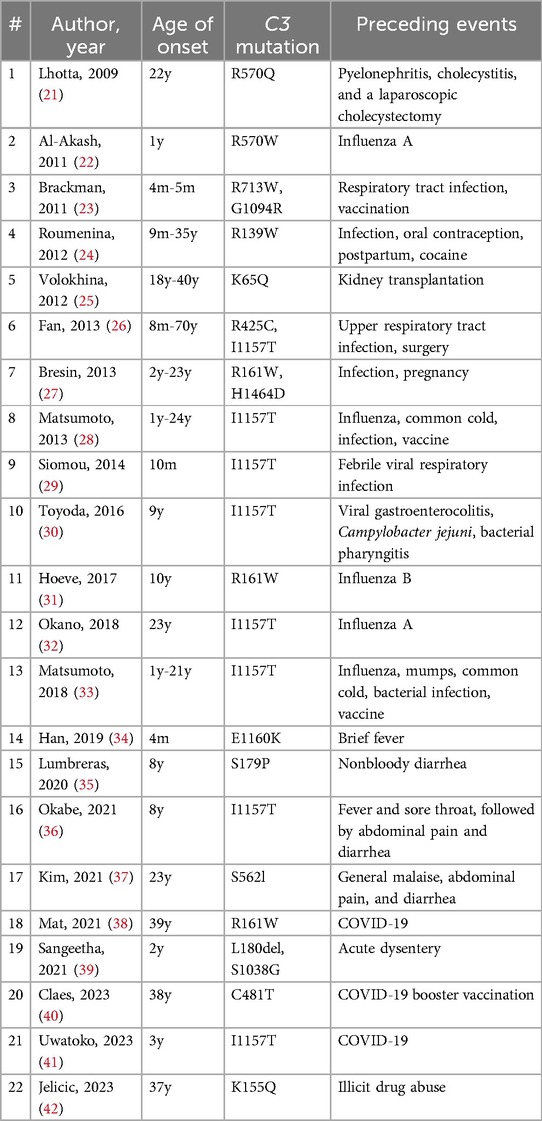

The C3 GOF variant is a relatively rare cause of aHUS globally, but this variant, particularly the C3 p.Ile1157Thr variant, is notably common in the Japanese population (20). This variant predisposes individuals to excessive complement activation by reducing the binding affinity of C3b to complement factor H (CFH) and/or membrane cofactor protein, or by conferring resistance to factor I-mediated inactivation of C3b (1). Patients with this genetic defect develop aHUS when complement activation becomes dysregulated, often in response to external triggers. While cases of aHUS with a C3 variant have been reported following a variety of preceding events, recent reports have increasingly linked COVID-19 to the development of aHUS (Table 2).

Table 2. Triggering events of aHUS in patients with a C3 variant.

Our patient, who had a known pathogenic C3 GOF variant, developed aHUS following COVID-19, despite having had other viral infections without subsequent aHUS earlier in his life. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may have a unique capacity to activate the alternative complement pathway, particularly in individuals with underlying complement system abnormalities. Recent studies have shown that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein activates the complement lectin pathway by interacting with mannose-binding lectin (MBL), a key component of the lectin pathway (43). It has also been shown that the SARS-CoV-2 N protein binds to mannose-binding protein-associated serine protease 2 (MASP-2) and activates the complement lectin pathway either directly or by potentiating MBL-dependent MASP-2 activation (44, 45). This results in the generation of C3 convertases, which can further activate the alternative complement pathway by cleaving C3 in plasma. In genetically predisposed individuals, this can lead to sustained and excessive alternative complement pathway amplification, resulting in the manifestation of aHUS.

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has been shown to compete with complement factor H (CFH) for binding to heparan sulfate on the cell surface, disrupting CFH's regulatory function (46). CFH normally limits complement activation by displacing Bb from C3 convertases and facilitating the cleavage of C3b by factor I. In the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, this regulation is impaired, which can lead to excessive activation of the alternative pathway and the onset of aHUS. These mechanisms illustrate the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to trigger complement-mediated diseases, especially in individuals with inborn defect in complement regulation.

Inborn errors of immunity have been noted as a risk factor for severe COVID-19. For example, abnormalities in genes related to type I interferons (IFNs) have been reported to underlie the severe form of COVID-19 (47). Their phenocopies, autoantibodies to type I IFNs, have also been reported to be associated with cases of life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia (48). Autosomal recessive deficiencies of OAS1, OAS2, and RNASEL have been reported as genetic etiological factors behind MIS-C, a rare and severe pediatric complication of COVID-19 (49). The present case report shows that patients with inborn errors of the complement system are also at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

This case reinforces the emerging understanding that COVID-19, even in the absence of severe respiratory symptoms, can trigger aHUS, particularly in individuals with genetic predispositions such as the C3 GOF variant. Clinicians should be vigilant for signs of aHUS in children with COVID-19, especially those with a family history of TMA or complement system abnormalities, as early diagnosis and intervention can lead to favorable outcomes.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsMA: Writing – original draft. KK: Writing – review & editing. SK: Writing – review & editing. MK: Writing – review & editing. NK: Writing – review & editing. HRO: Writing – review & editing. SN: Writing – review & editing. YM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HDO: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number JP21K07770 and Health and Labour Science Research Grants for Research on Intractable Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (Grant Numbers 23809798 and 23809849), and by AMED (Grant Numbers 23812233 and 23808661).

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Dr. Noritoshi Kato, Department of Nephrology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan, for the measurement of anti-factor H antibodies. The authors also thank Dr. Tomonori Kadowaki, Department of Pediatrics, Graduate School of Medicine, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan, for caring for the patient while he was in hospital. The authors also thank Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References2. Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Cunningham-Rundles C, Franco JL, Holland SM, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2022 update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee. J Clin Immunol. (2022) 42(7):1473–507. doi: 10.1007/s10875-022-01289-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Vrečko MM, Rigler AA, Večerić-Haler Ž. Coronavirus disease 2019-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: literature review. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(19):11307. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911307

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Moradiya P, Khandelwal P, Raina R, Mahajan RG. Systematic review of individual patient data COVID-19 infection and vaccination-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Kidney Int Rep. (2024) 9(11):3134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2024.07.034

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Alizadeh F, O'Halloran A, Alghamdi A, Chen C, Trissal M, Traum A, et al. Toddler with new onset diabetes and atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome in the setting of COVID-19. Pediatrics. (2021) 147(2):e2020016774. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016774

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Dalkıran T, Kandur Y, Kara EM, Dağoğlu B, Taner S, Öncü D. Thrombotic microangiopathy in a severe pediatric case of COVID-19. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. (2021) 15:11795565211049897. doi: 10.1177/11795565211049897

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Khandelwal P, Krishnasamy S, Govindarajan S, Kumar M, Marik B, Sinha A, et al. Anti-factor H antibody associated hemolytic uremic syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Nephrol. (2022) 37(9):2151–6. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05390-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Nomura E, Finn LS, Bauer A, Rozansky D, Iragorri S, Jenkins R, et al. Pathology findings in pediatric patients with COVID-19 and kidney dysfunction. Pediatr Nephrol. (2022) 37(10):2375–81. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05457-w

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Quekelberghe CV, Latta K, Kunzmann S, Grohmann M, Hansen M. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome induced by SARS-CoV2 infection in infants with EXOSC3 mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. (2022) 37(11):2781–4. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05566-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Searcy K, Jagadish A, Pichilingue-Reto P, Baliga R. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in a toddler. Case Rep Pediatr. (2022) 2022:3811170. doi: 10.1155/2022/3811170

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Matošević M, Kos I, Davidović M, Ban M, Matković H, Jakopčić I, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in the setting of COVID-19 successfully treated with complement inhibition therapy: an instructive case report of a previously healthy toddler and review of literature. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:1092860. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1092860

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Mocanu A, Bogos RA, Lazaruc TI, Cianga AL, Lupu VV, Ioniuc I, et al. Pitfalls of thrombotic microangiopathies in children: two case reports and literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). (2023) 13(7):1228. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13071228

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Yilmaz EK, Cebi MN, Karahan I, Saygılı S, Gulmez R, Demirgan EB, et al. COVID-19 associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Nephrology (Carlton). (2023) 28(10):557–60. doi: 10.1111/nep.14225

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Döven SS, Vatansever ED, Karabulut YY, Özmen BÖ, Durak F, Delibaş A. A pediatric case with hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with COVID-19, which progressed to end-stage kidney disease. Turk J Pediatr. (2024) 66(2):251–6. doi: 10.24953/turkjpediatr.2024.4524

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Domínguez-Rojas J, Campano W, Tasayco J, Siu-Lam A, Ortega-Ocas C, Atamari-Anahui N. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with COVID-19 in a critically ill child: a Peruvian case report. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. (2022) 79(2):123–8. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.21000061

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Al-Antary ET, Arar R, Persaud Y, Fathalla BM, Rajpurkar M, Bhambhani K. Unusual presentation of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in a newly diagnosed pediatric patient with systemic lupus erythematosus in the setting of MIS-C. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2022) 44(3):e812–5. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002370

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Tripathi AK, Pilania RK, Bhatt GC, Atlani M, Kumar A, Malik S. Acute kidney injury following multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. (2023) 38(2):357–70. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05701-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Grewal MK, Gregory MJ, Jain A, Mohammad D, Cashen K, Ang JY, et al. Acute kidney injury in pediatric acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): is there a difference? Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:692256. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.692256

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Generalić A, Davidović M, Kos I, Vrljičak K, Lamot L. Hematuria as an early sign of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: a case report of a boy with multiple comorbidities and review of literature. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:760070. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.760070

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Fujisawa M, Kato H, Yoshida Y, Usui T, Takata M, Fujimoto M, et al. Clinical characteristics and genetic backgrounds of Japanese patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol. (2018) 22(5):1088–99. doi: 10.1007/s10157-018-1549-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Lhotta K, Janecke AR, Scheiring J, Petzlberger B, Giner T, Fally V, et al. A large family with a gain-of-function mutation of complement C3 predisposing to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, microhematuria, hypertension and chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2009) 4(8):1356–62. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06281208

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Al-Akash SI, Almond PS, Savell VH Jr, Gharaybeh SI, Hogue C. Eculizumab induces long-term remission in recurrent post-transplant HUS associated with C3 gene mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. (2011) 26(4):613–9. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1708-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Brackman D, Sartz L, Leh S, Kristoffersson AC, Bjerre A, Tati R, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy mimicking membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2011) 26(10):3399–403. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr422

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Roumenina LT, Frimat M, Miller EC, Provot F, Dragon-Durey MA, Bordereau P, et al. A prevalent C3 mutation in aHUS patients causes a direct C3 convertase gain of function. Blood. (2012) 119(18):4182–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383281

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Volokhina E, Westra D, Xue X, Gros P, van de Kar N, van den Heuvel L. Novel C3 mutation p.Lys65Gln in aHUS affects complement factor H binding. Pediatr Nephrol. (2012) 27(9):1519–24. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2183-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Fan X, Yoshida Y, Honda S, Matsumoto M, Sawada Y, Hattori M, et al. Analysis of genetic and predisposing factors in Japanese patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Mol Immunol. (2013) 54(2):238–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.12.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Bresin E, Rurali E, Caprioli J, Sanchez-Corral P, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, de Cordoba SR, et al. Combined complement gene mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome influence clinical phenotype. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2013) 24(3):475–86. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012090884

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Matsumoto T, Fan X, Ishikawa E, Ito M, Amano K, Toyoda H, et al. Analysis of patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome treated at the mie university hospital: concentration of C3 p.I1157T mutation. Int J Hematol. (2014) 100(5):437–42. doi: 10.1007/s12185-014-1655-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Siomou E, Gkoutsias A, Serbis A, Kollios K, Chaliasos N, Frémeaux-Bacchi V. aHUS associated with C3 gene mutation: a case with numerous relapses and favorable 20-year outcome. Pediatr Nephrol. (2016) 31(3):513–7. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3267-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Toyoda H, Wada H, Miyata T, Amano K, Kihira K, Iwamoto S, et al. Disease recurrence after early discontinuation of eculizumab in a patient with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with complement C3 I1157T mutation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2016) 38(3):e137–139. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000505

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. van Hoeve K, Vandermeulen C, Ranst MV, Levtchenko E, van den Heuvel L, Mekahli D. Occurrence of atypical HUS associated with influenza B. Eur J Pediatr. (2017) 176(4):449–54. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2856-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Okano M, Matsumoto T, Nakamori Y, Ino K, Miyazaki K, Fujieda A, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with C3 p.I1157T missense mutation successfully treated with eculizumab. Rinsho Ketsueki. (2018) 59(2):178–81. doi: 10.11406/rinketsu.59.178

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Matsumoto T, Toyoda H, Amano K, Hirayama M, Ishikawa E, Fujimoto M, et al. Clinical manifestation of patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with the C3 p.I1157T variation in the kinki region of Japan. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2018) 24(8):1301–7. doi: 10.1177/1076029618771750

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Han SR, Cho MH, Moon JS, Ha IS, Cheong HI, Kang HG. Life-threatening extrarenal manifestations in an infant with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by a complement 3-gene mutation. Kidney Blood Press Res. (2019) 44(5):1300–5. doi: 10.1159/000502289

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Lumbreras J, Subias M, Espinosa N, Ferrer JM, Arjona E, de Córdoba SR. The relevance of the MCP risk polymorphism to the outcome of aHUS associated with C3 mutations. A case report. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01348

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Okabe M, Kobayashi A, Marumoto H, Koike K, Yamamoto I, Kawamura T, et al. Renal damage in recurrent atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with C3 p.Ile1157Thr gene mutation. Intern Med. (2021) 60(6):917–22. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.5716-20

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim YH, Jin SY, Kim HJ, Oh D, et al. Eculizumab therapy on a patient with co-existent lupus nephritis and C3 mutation-related atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome: a case report. BMC Nephrol. (2021) 22(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02293-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Mat O, Ghisdal L, Massart A, Aydin S, Goubella A, Blankoff N, et al. Kidney thrombotic microangiopathy after COVID-19 associated with C3 gene mutation. Kidney Int Rep. (2021) 6(6):1732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.897

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Sangeetha G, Jayaraj J, Ganesan S, Puttagunta S. Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: a case of rare genetic mutation. BMJ Case Rep. (2021) 14(7):e244190. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-244190

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Claes KJ, Geerts I, Lemahieu W, Wilmer A, Kuypers DRJ, Koshy P, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome occurring after receipt of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine booster: a case report. Am J Kidney Dis. (2023) 81(3):364–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.07.012

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Uwatoko R, Shindo M, Hashimoto N, Iio R, Ueda Y, Tatematsu Y, et al. Relapse of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome triggered by COVID-19: a lesson for the clinical nephrologist. J Nephrol. (2023) 36(5):1439–42. doi: 10.1007/s40620-023-01595-y

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Jelicic I, Kovacic V, Luketin M, Mikacic M, Skaro DB. Atypical HUS with multiple complement system mutations triggered by synthetic psychoactive drug abuse: a case report. J Nephrol. (2023) 36(8):2371–3. doi: 10.1007/s40620-023-01646-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Stravalaci M, Pagani I, Paraboschi EM, Pedotti M, Doni A, Scavello F, et al. Recognition and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 by humoral innate immunity pattern recognition molecules. Nat Immunol. (2022) 23(2):275–86. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01114-w

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Ali YM, Ferrari M, Lynch NJ, Yaseen S, Dudler T, Gragerov S, et al. Lectin pathway mediates complement activation by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:714511. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.714511

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Gao T, Zhu L, Liu H, Zhang X, Wang T, Fu Y, et al. Highly pathogenic coronavirus N protein aggravates inflammation by MASP-2-mediated lectin complement pathway overactivation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2022) 7(1):318. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01133-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Yu J, Gerber GF, Chen H, Yuan X, Chaturvedi S, Braunstein EM, et al. Complement dysregulation is associated with severe COVID-19 illness. Haematologica. (2022) 107(5):1095–105. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279155

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Zhang Q, Bastard P, Liu Z, Pen JL, Moncada-Velez M, Chen J, et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. (2020) 370(6515):eabd4570. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4570

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Bastard P, Rosen LB, Zhang Q, Michailidis E, Hoffmann HH, Zhang Y, et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. (2020) 370(6515):eabd4585. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585

留言 (0)