Sex work (SW) as a societal aspect is highly controversial (1). Estimated numbers suggest that globally, 40–42 million people are involved in SW with over 80% of them being women (2). While a proportion of female sex workers consider it a profession, an act of emancipation and self-determination, another proportion works under coercion (total proportions unknown). Regardless of their working conditions, sex workers often face societal stigma and marginalization (3). On the other hand, there are dissenting opinions regarding SW as an act of mostly male violence against women and as a harmful and traumatic experience (4, 5). Additionally, SW is linked to criminal activities such as human trafficking for sexual exploitation, drug abuse, and procurement in certain cases (6, 7). Previous research exploring the physical and mental health challenges encountered by sex workers, predominantly focused on particular concerns like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (8) but also discussed various factors related to mental health such as childhood maltreatment and traumatization (with prevalences ranging up to 56.8%) as well as experiencing violence in this profession (with prevalences ranging up to 69.6% for experiencing physical attacks) (9, 10). Studies exploring the connection between prostitution, a history of childhood sexual abuse, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other stress-related disorders reveal higher prevalences in sex workers compared to control groups (e.g., 26.2% among sex workers vs. 10.3% among the control group for PTSD) (10, 11). Additionally, the high level of violence experienced by sex workers has been linked to mental health issues and was addressed in previous studies, showing, e.g., that individuals who experienced any or combined forms of violence (physical, sexual, verbal) in the workplace are 1.76 times more likely to have depression compared to those who did not experience such violence (12). Research indicates that sex workers encounter violence more frequently than comparison groups before entering SW. Therefore, it is likely that sex workers, like other marginalized groups, exhibit poorer mental health compared to the general population (13–15). A study in Switzerland revealed high 1-year prevalences of mental disorders among female sex workers, associated with experiences of violence and the perceived burden of SW: annual prevalences of affective disorders were found to be six times higher than in the general population, similar to anxiety disorders (16). The frequency of mental disorders is linked to specific working conditions (e.g., in escort services, brothels or street prostitution). According to Rossler et al. (16), for example, 12% of women working in a street setting were found to display current PTSD symptoms, while none of the women in a studio setting were affected by PTSD (14, 16). Migration background of sex workers and therefore the right of residence also plays a significant role in shaping these conditions. In Zurich, for example, a prevalence of 47% for depression was found among migrant sex workers while only 10% of Swiss women suffered from depression (16). The findings underscore that the psychological challenges faced by sex workers are partially tied to job-specific risks, including exposure to violence and the lack of adequate social support (8).

Comprehensive data on sex workers’ mental health, the burdens they face, and, in this context, the role of violence are limited. To address this gap and compile stress and resilience factors contributing to the mental health of female sex workers were the aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis. The review seeks to quantify the prevalence of common mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, depression, PTSD, suicidality, and substance use among female sex workers as well as provide an overview of the effect sizes of associated risk and resilience factors. Thereby, we aim to highlight important public health issues and outline current research gaps. By aggregating data from various studies for the prevalences of several mental diseases, this meta-analysis provides a more robust estimate of the mental health burden in this population. Additionally, we conduct a subgroup analysis based on the legal situation (legal, partially legal and illegal), as well as on the national economic situation based on the gross domestic product (GDP). Specific subgroups of female sex workers, namely those living with HIV, drug-using sex workers, migrant sex workers, and survivors of sex trafficking, will be tested as mediators of prevalences. To provide a comprehensive analysis, this systematic review and meta-analysis include studies from a wide range of geographic regions without any geographical restrictions.

2 MethodsThis review was preregistered on Prospero (ID: CRD42022312737) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted as part of a cross-sectional prevalence study regarding the mental health of sex workers in Berlin. The project was funded by the German Research Association (DFG); the grant ID is GZ: SCHO 772/4–1 and GZ: RO 948/7–1.

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe studies included in the review had to meet the following criteria: (a) be quantitative studies with samples made up of sex workers and/or other population groups for comparative purposes; (b) be written in English or German; (c) be published after 2002 in peer-reviewed journals; (d) include a sample composed of adult female sex workers (18–65 years); and (e) investigate the relationship between sex work and mental health issues such as depression, suicidality, anxiety, substance abuse, psychotic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, and others risk and resilience factors. Qualitative studies were excluded, as well as studies not providing data on mental health, studies focused on sexually transmittable diseases (STDs), and studies focused on men, trans-gender sex workers or minors as they probably have different biographic experiences, issues with self-esteem, and stigma. The outcomes of interest were prevalences of mental disease and risk and resilience factors for mental disorders among female sex workers. Experience of violence and childhood trauma were considered as risk factors for mental disorders. The prevalence of violence and childhood trauma as primary outcomes was not assessed in this study, due to the amount of available literature.

2.2 Search strategyRayyan 20 (17) was used to screen the literature. The search was conducted in Medline via Web of Science, Cochrane, PubPsych, Embase Classic + Embase, and APA PsycINFO via EBSCOhost. A systematic search was performed including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms as well as specific keywords related to the topic of research. The MeSH terms used in our search strategy are provided in the Supplementary Table 1, which also includes the search terms for all databases where the search was conducted. The Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategy (PRESS) checklist (18) was used to control the correct conduction of literature research. All searches were performed in English or German. The search was restricted to articles published between 2002 and 2023 to ensure that the analysis reflects the most relevant and up-to-date research on the mental health of female sex workers. Following the global recognition of the HIV epidemic and its impact on sex workers in the early 2000s, there was a surge in research focusing not only on physical health but also on the mental health outcomes of female sex workers. This period thus represents a turning point where mental health became a more central component of research related to sex workers. We initially set out to investigate studies from the past 20 years, starting our review preparations in 2022. The first literature search was conducted in October 2023. In January 2024, we updated the literature search to include studies from 2023 to ensure that our analysis reflects the most current research and developments in the field. A manual search of the reference lists of included studies was conducted to identify additional relevant publications. We chose this approach because the research of interest is highly resource-intensive (e.g., time-consuming regarding participant recruitment or financially in terms of participation incentives and staff salaries), and we determined that scientific journals would likely provide a more comprehensive and reliable source of relevant literature compared to grey literature, such as policy papers or blog posts. The search was conducted in multiple steps and performed by three professional independent staff members, of which one had an academic background in psychology, one in psychology and public health, and one in medicine. First, a title screening was conducted. Secondly, an abstract screening was performed and followed by a full-text screening. Each screening was conducted by the three staff members and disagreements were resolved in each case by checking the full text for the inclusion criteria (see section 2.1).

2.3 Data extraction and quality of studiesFor each study, the staff members who conducted the screening extracted the following data into an Excel® spreadsheet: ID, topic, first author, year of publication, title, journal, volume, place, country, study design, setting, population, sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria, recruitment, interventions, start-end date, main outcomes/assessment points, study instruments and quality of study instruments, comparison/control group, main findings, size of effect. For a comprehensive overview, we report the following data from the studies that met the inclusion criteria in this review and meta-analysis: Author, year, the legal status of sex work, sample size and population, study design, recruitment strategy, as well as measurements of the outcome variables and results. The methodological quality of all included studies was assessed by the same three staff members independently and systematically, using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). Only studies using validated standardized instruments and scoring at least 3 points were included.

2.4 Meta-analysisMeta-analysis was conducted using the “metafor” package in R (19, 20). We calculated the logit-transformed prevalence from the reported prevalence rates to stabilize the variances and used the reported confidence intervals to calculate the standard errors of the logit-transformed prevalence. If the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were not reported, we calculated the 95% CI from the sample size and the given prevalence using the Wilson score method, as it provides more accurate confidence intervals particularly when dealing with proportions close to the boundaries (0 or 1) or when sample sizes are relatively small (21). We adopted a random-effects model due to the anticipated heterogeneity among studies, quantified using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the potential effects of poverty (assessed through the country’s GDP per capita), legal status of sex work, specific sub-populations, and assessment method [clinical interview versus other (self-) assessment tool] on prevalence. We hypothesized that the economic status of a country, as indicated by GDP per capita, influences access to essential resources such as food, water, and healthcare, which in turn may mediate the prevalence of mental health conditions. While GDP per capita is not a direct measure of resource access, it is widely used as a proxy for a country’s overall economic capacity to provide these resources. To capture these effects, we analyzed the data using meta-regression to examine the relationship between GDP per capita, treated as a continuous variable, and the effect sizes of mental health outcomes across studies. Legal status was considered as a categorical variable, reflecting the legal framework governing sex work in the study location: “legal,” “partially legal,” and “illegal.” “Partially legal” comprises legislature where, e.g., sex work is legal, but running sex work establishments, such as brothels, is illegal. Population subgroups included, e.g., sex workers living with HIV, drug-using sex workers, or survivors of human trafficking. To account for the risk of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, we applied a Bonferroni correction (22) by adjusting the significance threshold to ∝=0.0512 (according to the total number of 12 mediator tests) ensuring that the findings reflect statistically significant effects not attributable to chance. The adjusted α is hence 0.0042. The presence of publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and further tested by Egger’s test. For the meta-analyses, further studies were excluded because they reported the prevalence relatively to comparison groups and did not provide prevalence numbers. We have set a limit of a minimal number of 10 available and qualitatively sufficient studies to conduct a meta-analysis. While we did not explicitly mention the minimum threshold of 10 studies in our preregistration, this criterion was implemented to ensure the reliability and validity of our results. This decision was guided by best practices in meta-analysis, which emphasize the importance of having enough data points to ensure that the results are statistically sound.

3 Results 3.1 Systematic reviewThis section provides a detailed overview of the prevalence, risk, and resilience factors for mental health conditions among female sex workers globally. The section is structured by conditions spanning from subclinical anxiety and anxiety disorders to depression, suicidality, PTSD, substance use, and dependence, as well as other conditions. Each sub-section reports the prevalence first (see Table 1) and the risk and resilience factors (see Table 2) second. Unless stated otherwise, the prevalences refer to current symptoms.

Table 1. Studies reporting the prevalence of mental conditions (anxiety, depression, PTSD, suicide and self-harm, substance use and dependence, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating-disorder, somatization disorder, schizophrenia, other) meeting the inclusion criteria of the systematic review.

Table 2. Risk and resilience factors for mental conditions among sex workers.

3.2 Study selectionA total of 3,952 studies were identified. First, duplicates (n = 903) were removed, leaving 3,049 studies for abstract and title screenings. Of these, 2037 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. From the remaining literature, 219 studies were eligible for full-text analysis. Three studies could not be retrieved (30–32). A total of 105 studies were excluded from the analysis for different reasons (i.e., focused on STDs or did not report the age, qualitative instead of quantitative measurements, etc.) the remaining 111 studies were included, and for 21 review articles citation tracking was used resulting in 24 studies for further full-text screening. A total of 20 studies were excluded from the analysis resulting in a total of 115 studies that were finally included. Figure 1 summarizes the selection process.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart summarizing the study selection process.

3.3 Quality assessmentAfter quality assessment, a total of 80 remaining studies were analyzed for the systematic review. Several studies (n = 23) were excluded from the systematic review due to the absence of standardized instruments for data collection. One publication was excluded because the used instruments were not described. Additionally, some publications were not included because they presented secondary data analyses with the original data already reported in previous publications (n = 7). We included only the original publications ensuring prevalences and risk factors were not reported twice. Four studies scored below 3 points on the Newcastle Ottawa Scale and therefore were excluded from the report according to our review methodology. Supplementary Table 2 presents an overview of the studies that did not meet the quality standards. The scores of the 80 included studies ranged from 3 to 9, with most studies scoring between 4 and 6. The distribution indicates that the majority of studies met a moderate level of quality, with a few outliers achieving higher scores of 7 or 9, while some scored lower, suggesting a more variable overall quality. Supplementary Table 3 provides an overview of the included studies and the quality scores. The included studies comprise a total of 24,675 individuals.

3.4 Geographic distribution of included studiesFigure 2 shows the global distribution of identified studies. The studies originate from 26 different countries. The majority of studies stemmed from the United States (n = 24), followed by China (n = 12), India (n = 7) and Kenya (n = 5). Four studies were conducted in South Africa and three in Mexico. Two studies originated from Australia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Netherlands, and Uganda. Single studies were identified from Scotland, Switzerland, Israel, Portugal, Mongolia, Malawi, Cameroon, Ukraine, Togo, Lebanon, the Dominican Republic, Tanzania, Puerto Rico, Ethiopia, and Moldova.

Figure 2. Global distribution of included studies.

3.5 Subclinical anxiety and anxiety disorders 3.5.1 Prevalence of subclinical anxiety and anxiety disordersThe prevalence of subclinical anxiety and anxiety disorders among sex workers has been studied across various global locations and populations through 14 studies (see Table 1), with four studies stemming from the USA and 10 single studies from Lebanon, Kenya, the Dominican Republic, China, Ethiopia, Scottland, Switzerland, India, Thailand and Moldova. A large proportion of the research utilized cross-sectional surveys to collect data, with several studies forming part of baseline data collection for broader intervention studies. For instance, Edwards et al. (26) and Risser et al. (33) both analyzed baseline data from intervention studies focusing on substance abusers who engage in sex work. Slim et al.’s work (34) differed as a case–control study, recruiting participants from a prison setting, while Beksinska et al. (35) utilized mixed methods. The instruments used to measure anxiety varied across studies. They include, e.g., the anxiety scale of the Drug Abuse Treatment AIDS Risk (DATAR) questionnaire (36), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (37), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder tool (GAD-7) (38), and modules from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (39).

A review of the literature reveals a wide range of anxiety prevalence among sex workers, from the lowest reported rate of 5.2% by Rossler et al. (16) for generalized anxiety disorder in Zurich, Switzerland to the highest of 75.8%, among migrant sex workers in Mae Sot, Thailand reported by Decker et al. (40).

In the lower prevalence range, Rossler et al. (16) reported rates for panic disorder (8.8%), simple phobia (17.6%), and agoraphobia without panic (2.1%), illustrating a spectrum of anxiety disorders among sex workers. Similarly, Iaisuklang et al. (41) found a prevalence of 8% for generalized anxiety disorder. Middle-range prevalences include findings from Gilchrist et al. (42) in Scotland, with 26% of sex workers experiencing phobias and 24% panic disorders. At the higher end of the spectrum, Ghafoori et al. (43) reported a 56.9% prevalence among survivors of sex trafficking, which was still lower than among the two comparison groups, namely survivors of domestic violence (70%) and sexual assault (79.3%).

3.5.2 Risk and resilience factors for anxietyAcross the 7 identified studies, a range of risk and resilience factors for anxiety have been identified (Table 2). Beksinska et al. (35) found that in Kenya, a higher prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) was associated with anxiety, with factors such as experiencing violence and war in childhood, missing meals due to lack of food, and non-consensual sexual debut being significant predictors. However, social support seemed to play a protective role. Mac Lin et al. (23) reported that sex work related police harassment significantly increased the likelihood of scoring abnormal on the anxiety-specific module of the HADS-A. Zhai et al. (27) identified that married female sex workers, those living in the county with low education, and those with social support were less likely to report anxiety. Quarantining due to the pandemic was an independent risk factor (27). Kelton et al. (44) found that greater current financial concern and lower social capital were linked to higher anxiety symptoms. Yesuf et al. (45) observed that street sex workers reported higher anxiety levels compared to those working from home, with khat use, violence, stigma, and tobacco use being significant predictors of anxiety. Lastly, Decker et al. (40) noted that anxiety was more prevalent among migrant sex workers who experienced fraud, force, or coercion.

3.6 Depression 3.6.1 Prevalence of depressionIn this section, we analyze the prevalence of depressive symptoms among sex workers through 41 studies conducted by various authors across different locations globally (see Table 1). Among these, most of the studies employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing both recruitment through agencies and snowball sampling strategies. The instruments and measures used to assess symptoms of depression varied across studies, including, e.g., the Center for Epidemiologic Survey-Depression Scale (CES-D) (46), the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (47), and the depression subscale from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (48).

This review presents a broad spectrum of prevalences of depressive symptoms among female sex workers, highlighting the complexity of mental health within this demographic. The analysis spans from the lowest reported prevalence of 3.3% for major depression (49) to the highest of 100% in a subgroup of female sex workers living with HIV reported by Mac Lin et al. (23).

Sherwood et al. (50) and Iaisuklang et al. (41) reported relatively low prevalences of 10.3 and 9% respectively, suggesting areas or conditions under which sex workers may experience comparatively better mental health outcomes. Contrasting these findings, Bhardwaj et al. (51) found 33.2%, indicating a relatively moderate level of depression among sex workers on the spectrum of included studies. Mid-range prevalences are represented by studies such as in the works of Rossouw et al. (52), Grudzen et al. (53) Abelson et al. (25) and Hong et al. (54). At the higher end of the spectrum, findings from Gilchrist et al. (42), and Coetzee et al. (55) reported prevalences of 70% and 68.7%.

Some studies focused on specific subgroups or included a comparison group. Ulibarri et al. (56), e.g., found that 86% of a subgroup of female sex workers who reported injection drug use exceeded the cutoff score for depression, highlighting the intersectionality of drug use and mental health challenges in this population (57). Other studies, such as those by Slim et al. (34) in Lebanon, and Risser et al. (33) in Houston, Texas, USA, showed higher depression scores among sex workers compared to non-sex workers, further evidenced by the findings of Kim et al. (58) in Chicago, Illinois, where sex workers showed a higher prevalence (81%) compared to persons engaged in care and service work.

3.6.2 Risk and resilience factors for depressionThis review identified a wide range of risk and resilience factors for depression among sex workers, underscoring the complexity and diversity of experiences within this population (see Table 2). The studies span multiple continents and encompass a variety of study designs (59, 60) as well as socioeconomic, behavioral, and interpersonal dimensions.

Socioeconomic factors, stigma, and experiences of violence emerged as the most extensively studied predictors of depression. Krumrei-Mancuso et al. (5) highlighted motivation for entering sex work as a significant determinant of depression, with economic motivation linked to higher depression levels. This contrasts with those entering for pleasure or a combination of reasons, suggesting the critical role of agency and motivation in mental health. Moreover, confidence in finding alternative employment served as a protective buffer against depression. Social support emerged as a strong protective factor in several studies, including Carlson et al.’s (61) work. Conversely, stigma and sexual violence were consistently identified as significant risk factors (24, 25, 35, 62, 63). A good relationship with gatekeepers, individuals who manage the establishments and/or sex workers, was a protective factor for depression (64).

Besides individual socioeconomic factors, psychiatric co-morbidities and systemic factors were identified as factors influencing the depression rates of sex workers. Early initiation into sex work, as suggested by MacLean et al.’s (65) study, and substance use severity (66) were implicated as contributors to higher depression rates. Coetzee et al. (67) and Stockton et al. (63) found that pregnancy, child loss, and food insecurity further complicate the relationship between personal circumstances and depression among female sex workers. Racial disparities and the impact of incarceration on mental health were noted in the United States by Murnan et al. (68) and Kim et al. (58), respectively, while living with HIV, and verbal abuse were associated with major depression in Northern Uganda (69). (Intimate partner) violence, alcohol use, Khat use, and age were identified as significant risk factors of depression (29, 45, 70). Institutional factors such as police harassment (23) and environmental factors like mobility and working conditions (71) were also recognized as influencing depression levels.

3.7 Suicide and self-harm 3.7.1 Prevalence of suicide and self-harmThe research designs applied in the 9 identified studies varied, including cross-sectional studies with and without control groups (see Table 1). Recruitment strategies ranged from reaching out to participants through agencies, community outreach, and specific locations such as streets and restaurants, to collaborations with health programs. Several instruments were utilized across the studies to measure suicide and self-harm behaviors as well as mental health indicators. These included the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) (72) and the Kessler 10 (K10) (73), among others.

The prevalence of suicidal behaviors among sex workers varies widely from lower incidences reported in Soweto, South Africa (67), with 3.6%, to notably higher rates in other regions and among specific subgroups. Multiple studies were focused on street-based and/or drug-using sex workers, who seem to display higher rates of suicidality. Gilchrist et al. (42) reported that 39% of drug-using sex workers engaged in deliberate self-harm, and 53% had attempted suicide, highlighting the severe mental health concerns within this demographic. Roxburgh et al. (9) found even more alarming figures in Sydney, Australia, where 74% of street-based female sex workers had contemplated suicide, and 42% had attempted it at least once, underscoring the critical mental health risks faced by sex workers. Ling et al. (74) identified that 25.8% of street-based sex workers had suicidal thoughts, and 6.7% reported attempting suicide. Similarly, Fang et al. (75) found that 14% considered suicide in the past 6 months, with 8% attempting suicide within the same timeframe. Zhang et al. (76) reported a prevalence of suicidal behavior at 9.5%. Teixeira et al. (77) reported that 44.2% of street-based participants stated having made at least one suicide attempt (78).

3.7.2 Risk and resilience factors for suicidalityThe collection of studies highlighted here examines the risk factors for suicidality among sex workers in various geographical locations (see Table 2). Socioeconomic factors, co-morbidities, violence and institutional factors such as law enforcement were identified as risk factors for suicidality. Ling et al. (74), e.g., identified frequent identity card checks as significant contributors to increased suicidality risk among sex workers. Hong et al. (28) reported that key factors linked to suicidality included educational level, cohabitation status, relationship issues, sexual coercion, and history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), highlighting the impact of interpersonal and health-related stressors. Shahmanesh et al. (79) in Goa observed that age, ethnicity, number of children, and length of residence were influential, with violence, entrapment, and having regular customers also noted as predictors of suicide attempts. Protective factors included non-migrant ethnicity, participation in HIV prevention interventions, and parenthood, indicating the potential of community and familial support systems in mitigating suicide risk. Like in the case of previously reported mental conditions, stigma emerged as risk factor for suicidality. Zhang et al. (80), e.g., discovered that violence from stable partners and clients, psychological abuse, and higher levels of stigma significantly increased the likelihood of suicidal ideation or attempts.

3.8 PTSD 3.8.1 Prevalence of PTSDOur systematic review delved into the prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among sex workers, incorporating 16 studies from diverse geographic locations (see Table 1). Among the included studies, a majority were cross-sectional in design, focusing on assessing the current prevalence and conditions among sex workers. The results of these studies highlighted a significant variation in PTSD prevalence among the sex worker populations studied, with the instruments used to measure PTSD symptoms including, e.g., the PTSD Checklist (PCL-5) (81), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (82), and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (83).

PTSD prevalences were notably linked to specific subgroups, namely street-based, drug-using sex workers and survivors of human trafficking. Roxburgh et al. (9) highlighted that nearly half (47%) of street-based female sex workers met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime PTSD prevalence, with 31% meeting the criteria for current PTSD. Cigrang et al. (84) observed a 66% PTSD prevalence among sex workers arrested for at least one drug offense. Hendrickson et al. (71) reported a 53% PTSD prevalence among street-based sex workers, while Suresh et al. (85) found that 42% had moderate PTSD symptoms and 12% had extreme symptoms. Farley et al. (86) focused on street sex workers, finding that 52% met all criteria for a PTSD diagnosis. Ostrovschi et al. (49) examined women returning to Moldova after being trafficked, noting a decrease in PTSD diagnoses from 48.3% in the crisis intervention phase to 35.8% in the re-integration phase.

Some studies implemented comparison groups. Ghafoori et al. (43) compared sex trafficking survivors with domestic violence and sexual assault victims, finding lower PTSD rates among the first (61.2%) compared to 70.5% and 83.6% in the second and third group, respectively. Edwards et al. (26) found that among African American crack abusers, those who traded sex were more likely to report PTSD symptoms than non-sex workers. Jung et al. (87) compared former sex workers to activists and a control group, finding the highest prevalence of PTSD symptoms among former sex workers.

The studies varied widely in sample sizes. Broader studies like Beksinska et al. (35) (n = 1,003) reported a PTSD prevalence of 14.2% among female sex workers, while smaller studies such as Chudakov et al. (88) in Israel (n = 55), found a 17% prevalence.

3.8.2 Risk and resilience factors for PTSDPTSD prevalences were mostly influenced by experience of violence, but socioeconomic factors also played significant roles. Roxburgh et al. (9) found a strong association between adult sexual assault, a higher number of traumas, and current PTSD among female sex workers, with no significant differences noted in child sexual abuse or physical assault at work based on PTSD status (see Table 2). Jung et al. (87) observed that the work duration and age positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity. Suresh et al. (85) reported that violence encountered by sex workers was a key factor in the heightened levels of depression and PTSD, indicating that violence, rather than the sex work itself, contributed significantly to their mental distress. Farley et al. (86) identified a direct correlation between PTSD symptom severity and lower health ratings among American Indian/Alaska Native women in sex work. The fact that PTSD prevalence is associated with the workplace and the specific subgroup, such as drug-using sex workers, is further evidenced by Alschech et al. (89), who observed that online independent sex workers in the USA and Canada had significantly lower PTSD scores compared to brothel workers, and Tomko et al. (90), who noted higher recent benzodiazepine use among women with high PTSD scores. Social circumstances were predictors of PTSD prevalences, as in the case of Stoebenau et al. (91), who found that PTSD likelihood was higher among women reporting sex work or transactional sex with a casual partner compared to those with a main partner only. Contrary to the previously named studies, Salina et al. (92) reported that past sexual coercion did not significantly affect trauma scores among women engaged in the sex trade, presenting a nuanced view of trauma’s role in sex work.

3.9 Substance use and substance dependence 3.9.1 Prevalence of hazardous alcohol use and alcohol dependenceIn the systematic review section, we delve into the findings of 14 studies that shed light on this topic across a global spectrum (see Table 1). The array of studies investigating alcohol use and dependence among sex workers employs a rich tapestry of study designs and instruments. Predominantly, the research leans toward cross-sectional designs, with notable variations in recruitment strategies that cater to the specific contexts and populations under study. For instance, Pandiyan et al. (66), and Couture et al. (93), employed cross-sectional approaches with participants recruited from either psychiatric hospitals or entertainment venues, respectively, underscoring the diversity in setting and approach. Tchankoni et al. (94) bio-behavioral study, and Rash et al. (95) baseline data from an intervention study illustrate the methodological breadth, ranging from respondent-driven sampling (67) to targeted sampling at various venues (51). A common thread is the utilization of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (96) and its concise counterpart, AUDIT-C (97). Other instruments included the Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (SMAST) (98), or, e.g., the WHO ASSIST tool (99).

Prevalences ranged from 100 to 0% for alcohol use and dependence. Pandiyan et al. (66) in Bangalore, India, found alcohol use to be universally prevalent among the study’s participants. Couture et al. (93) in Cambodia reported that a significant majority of female sex workers and male clients engaged in hazardous drinking, with an 85% prevalence rate according to the AUDIT-C scale. In Togo, Africa, Tchankoni et al. (94) found that 77% of female sex workers used alcohol at harmful or hazardous levels, with Lichtwarck et al. (100) reporting a slightly lower but still high prevalence rate of 69.6%. Some studies found lower rates of 26.3% and 29.8%, respectively, (51, 101). Stoebenau et al. (91) observed a 45.9% prevalence among sex workers compared to 14% among non-sex workers, highlighting a significant disparity. Griffith et al. (102) found problematic drinking levels among porn actresses to be similar to those of the general population while Rossler et al. (16) reported a 0% prevalence of alcohol dependence.

3.9.2 Prevalence of substance use and dependence (other than alcohol)The systematic review on substance use among sex workers encompasses findings from 16 studies conducted in diverse locations (see Table 1). The applied study designs include intervention studies utilizing baseline data (103), cross-sectional studies with (42) and without control groups (41), and mixed methods approaches (104). Some studies employed specific recruitment strategies such as venue-based sampling (33) others used health records (95). The instruments used to measure substance use varied across studies, incorporating tools like hair assays for detecting cocaine and opiate use (103), or, e.g., the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for assessing drug dependency and psychiatric diagnoses (105). Instruments such as, e.g., the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (106), and the Drug Abuse Screening Test–10 (DAST-10) (107) were utilized to quantify the extent of substance dependence and to evaluate the associated risks and health concerns in diverse geographic and sociocultural contexts.

The identified studies were mostly focused on street-based sex workers. Nuttbrock et al. (103) in New York City, USA, found that among street-based sex workers, 92.7% had used cocaine and 44.4% had used opiates in the month before testing. Gilchrist et al. (42) observed a high level of polydrug use, with 79% of sex workers reporting such use in the last 30 days, including 18% for cocaine use and 72% for injecting drugs, with 55% experiencing accidental drug overdoses. Kurtz et al. (104) reported widespread substance use among sex workers, including crack cocaine (73.4%), and marijuana (59.9%), among others. Risser et al. (33) highlighted longer durations and higher frequencies of crack use among current sex workers. Broader studies, such as in the case of Beksinska et al. (101), reported harmful levels of amphetamine (21.5%) and cannabis use (16.8%) among female sex workers, with a minor fraction reporting injecting drug use (0.5%). Some studies reported a comparison group: Vaddiparti et al. (108) observed a disparity in cocaine dependence between sex workers and non-sex workers, while Rash et al. (95) found no significant difference in opioid use disorder between the two groups. While cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, and cannabis were the substances most commonly used by sex workers, only a small fraction appeared to consume psychoactive substances overall. Iaisuklang et al. (41) in Shillong, Meghalaya, India, e.g., reported a small percentage (3%) of female sex workers were diagnosed with non-alcohol psychoactive substance use disorder.

3.9.3 Risk and resilience factors for substance use and substance dependence (including alcohol)Due to limited literature in this field (6 identified studies), risk factors will not be reported separately for substance use, substance dependence as well as hazardous alcohol use and alcohol dependence (see Table 2). Socioeconomic factors and experiences of violence were identified as the predominant risk factors, though more specific factors, such as genetic predisposition, were also noted. Zhang et al. (109) identified younger age, unmarried status, higher education levels, and employment in alcohol-serving venues as factors increasing the propensity for alcohol-related problems among female sex workers. This group was also at a heightened risk of sexual exploitation and violence by clients, with a correlation noted between the severity of drinking behavior and these risks. Chen et al. (110) found that female sex workers with at least a high-school education, married status, and higher monthly income exhibited higher alcohol risk levels. L’Engle et al. (111) demonstrated the effectiveness of targeted behavioral interventions in reducing drinking levels among moderate-risk drinking female sex workers through a randomized controlled trial. In Cambodia, Couture et al. (93) observed higher rates of unhealthy alcohol consumption among female sex workers employed in entertainment venues and those with children, noting the significant influence of education level on alcohol consumption patterns among male clients. Zhang et al. (112) pointed out that female sex workers with first and second-degree relatives who drank alcohol had higher AUDIT scores, suggesting genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol use disorders. Further research by Beksinska et al. (101) indicated that female sex workers with harmful alcohol use reported higher ACE scores, street living, and experiences of childhood sexual/physical violence, emphasizing the need for early interventions to address these complex interrelations. Similarly, Roxburgh et al. (113) noted that sexual violence was a risk factor for substance abuse. Lichtwarck et al. (100) found that a history of arrest/incarceration, experiencing gender-based violence, and mobility for sex work significantly raised the prevalence of harmful alcohol use among female sex workers. Boog et al. (114) found no statistical differences in drug use intensity compared to non-sex workers when adjusted for age and level of education, suggesting that drug use patterns among sex workers may not be distinctly different from other groups.

3.10 Other conditions 3.10.1 Prevalence of personality disorders, eating disorders, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and other disordersA variety of instruments have been employed across these studies to measure and evaluate mental health outcomes (see Table 1). These include the composite International Diagnostic Interview (115), the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV) (116, 117), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (118), the Kessler Scale (73), and clinical interviews based on ICD-10 and DSM 5 criteria. The studies’ designs ranged from cross-sectional with different recruitment strategies, including outreach and agency recruitment, baseline data from intervention studies (119–121), longitudinal studies following up survivors of human trafficking, to cross-sectional studies with control groups (122).

Rossler et al. (16) found a 0% one-year and lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia among sex workers but noted a 10.4% one-year prevalence and an 11.4% lifetime prevalence for somatoform disorders. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) prevalence rates were both reported at 2.1% for 1 year and lifetime. The one-year prevalence for eating disorders was 5.2%. Jiwatram-Negron et al. (123) highlighted significant mental health issues among female sex workers, with 30% reporting hospitalization for mental health concerns at some point, and sex traders experiencing notably higher rates of hospitalization compared to non-trading women. Edwards et al. (26) identified that female sex workers had a significantly higher mean score on the PCL:SV Psychopathy measure compared to controls. Iaisuklang et al. (41) reported that 9% of participants had been diagnosed with Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD). Ostrovschi et al. (49) found initial diagnoses of Somatization Disorder (2.5%), Adjustment Disorder (13.3%), and Acute Stress Reaction (10%) among survivors of human trafficking during the crisis intervention phase, which were not present during the re-integration phase. Gilchrist et al. (42) reported a compulsion prevalence of 37%, an obsession prevalence of 53%, and a lifetime prevalence of 37% for eating disorders among sex workers.

3.10.2 Meta-analysis of prevalences of mental diseaseA random-effects meta-analysis was conducted for “Subclinical Anxiety or Anxiety Disorder” (k = 10), “Depression” (k = 29) and “PTSD” (k = 13). The available literature for other disease prevalences or risk factors was not sufficient to conduct a meta-analysis. All studies included in the meta-analysis captured the prevalence of current symptoms, not the lifetime prevalence. While the studies on depression and PTSD captured symptoms that were indicative of the diagnosis, the studies on anxiety focused either on screening for anxiety disorders according to ICD or DSM (e.g., through the Composite International Diagnostic Interview) or on a screening for elevated anxiety levels, that indicate the need of further clinical diagnostics and treatment (e.g., through the Beck Anxiety Inventory). A subgroup analysis was conducted for each condition testing the legal status of sex work (using the categories “legal,” “partially legal” and “illegal”), the sub-population, and economic conditions (GDP per Capita) as mediators. Additionally, we conducted a subgroup analysis for each condition to examine whether the method of assessment (clinical interview versus other assessment tool) influenced the reported prevalence rates. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plots and the Egger’s test.

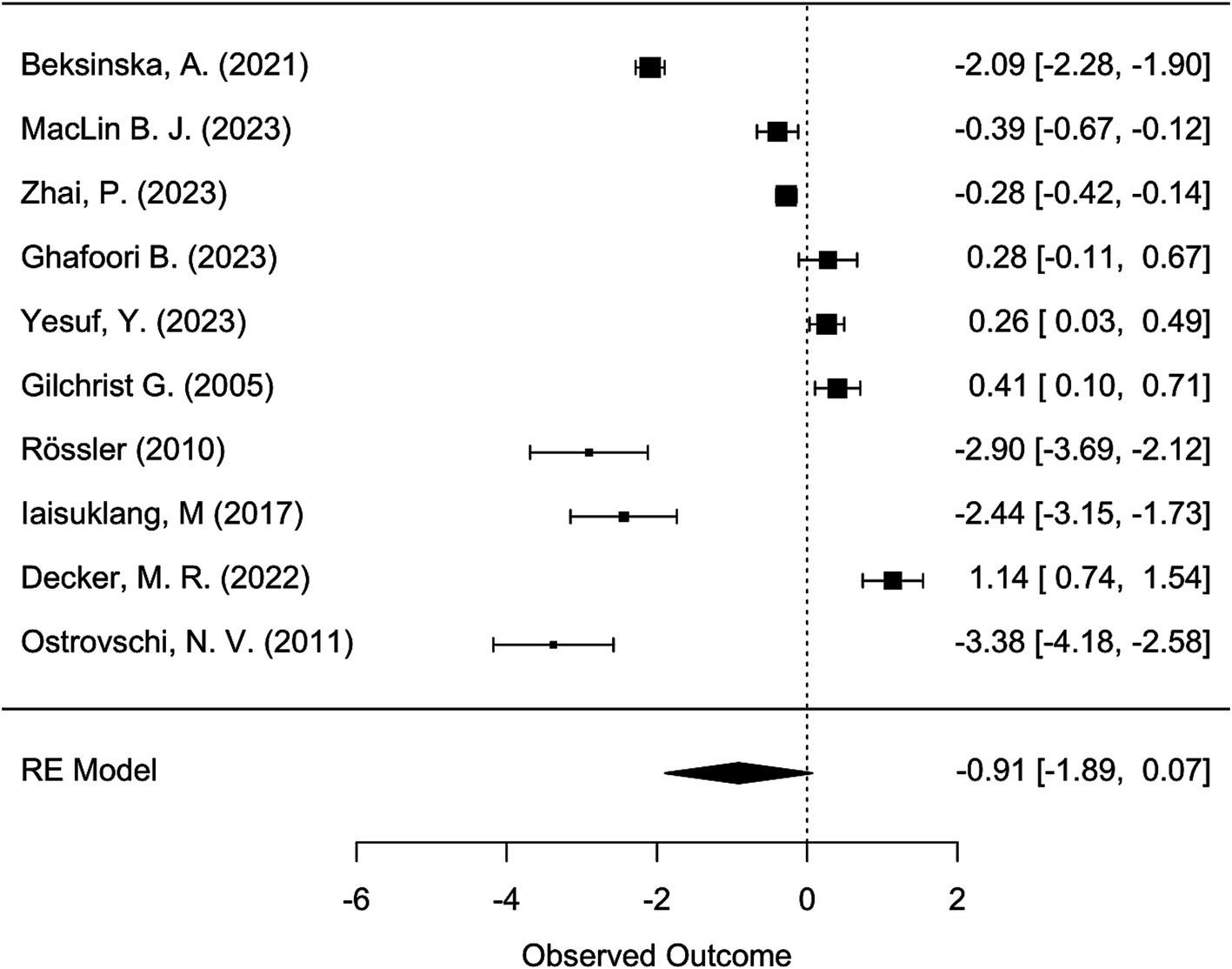

3.11 Anxiety 3.11.1 Overall findings on anxiety prevalenceThe random-effects model analysis underscored a profound heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 99.14%), highlighting the complexity of generalizing anxiety prevalence across diverse sex worker populations. The model indicated a non-significant pooled effect size (p = 0.0686), suggesting that while there might be a trend toward increased anxiety levels, this did not uniformly manifest across all included studies. This result, coupled with the high degree of variability (tau2 = 2.4458), signals the multifaceted nature of anxiety prevalence among sex workers, necessitating a closer examination of specific subgroup characteristics that might influence these outcomes. Please refer to Figure 3 for the forest plot showcasing the prevalence of subclinical anxiety or anxiety disorder.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the logit-transformed prevalence of subclinical anxiety and anxiety disorder and calculated confidence intervals across the included studies.

3.11.2 Subgroup analysis: legal status of sex workThe mixed-effects model exploring the impact of legal status on anxiety prevalence revealed that this factor did not significantly explain the heterogeneity observed across studies (p = 0.6247).

3.11.3 Subgroup analysis: populationFurther subgroup analysis focused on specific demographics within the sex worker population, including those living with HIV, drug-using sex workers, female sex workers, migrant sex workers, and survivors of sex trafficking. This analysis highlighted significant residual heterogeneity (I2 = 99.31%), indicating considerable variability in anxiety prevalence across these groups. Subpopulation was not a significant mediator of anxiety prevalence (p = 0.0526).

3.11.4 Subgroup analysis: economic conditionsThe examination of economic conditions did not yield significant findings (p = 0.8794). This analysis suggests that within the context of this meta-analysis, economic conditions do not have a significant direct impact on anxiety prevalence among sex workers.

3.11.5 Subgroup analysis: assessment methodThe subgroup analysis revealed that the assessment method is not a significant moderator (p = 0.0358) given the adjusted significance level of α = 0.0042. The results indicated significant residual heterogeneity (I2 = 98.84%).

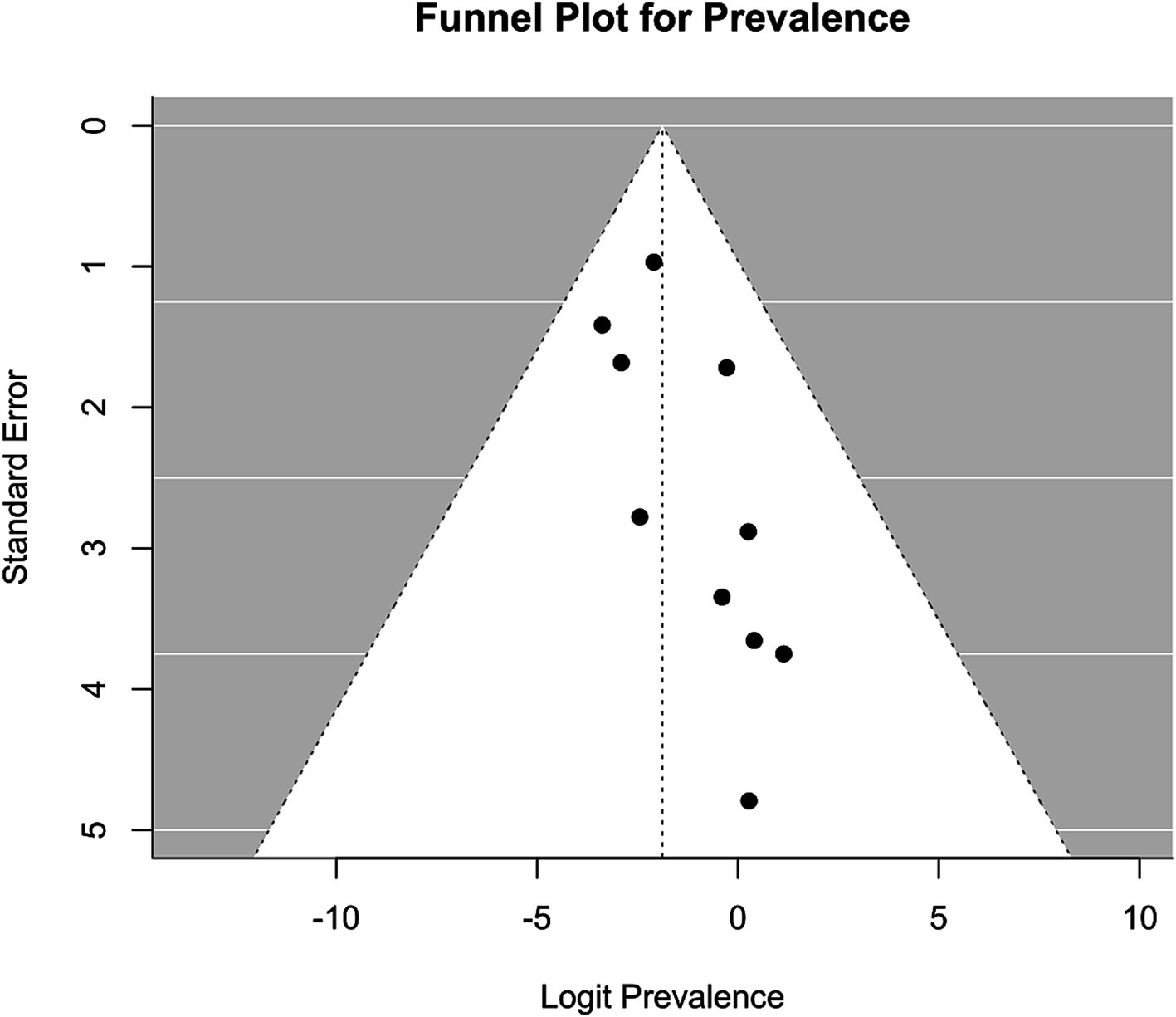

3.11.6 Assessment of publication BiasTo evaluate the potential impact of publication bias on our meta-analysis results, we conducted Egger’s test. Upon conducting Egger’s test, we obtained a p-value of 0.6297748. This non-significant result indicates no strong evidence of funnel plot asymmetry or publication bias in our meta-analysis dataset. Please refer to Figure 4 for the funnel plot. The absence of significant publication bias provides increased confidence in the robustness of our meta-analysis findings.

Figure 4. Funnel plot assessing publication bias in logit-transformed subclinical anxiety and anxiety disorder prevalences (X-axis) and standard error (Y-axis).

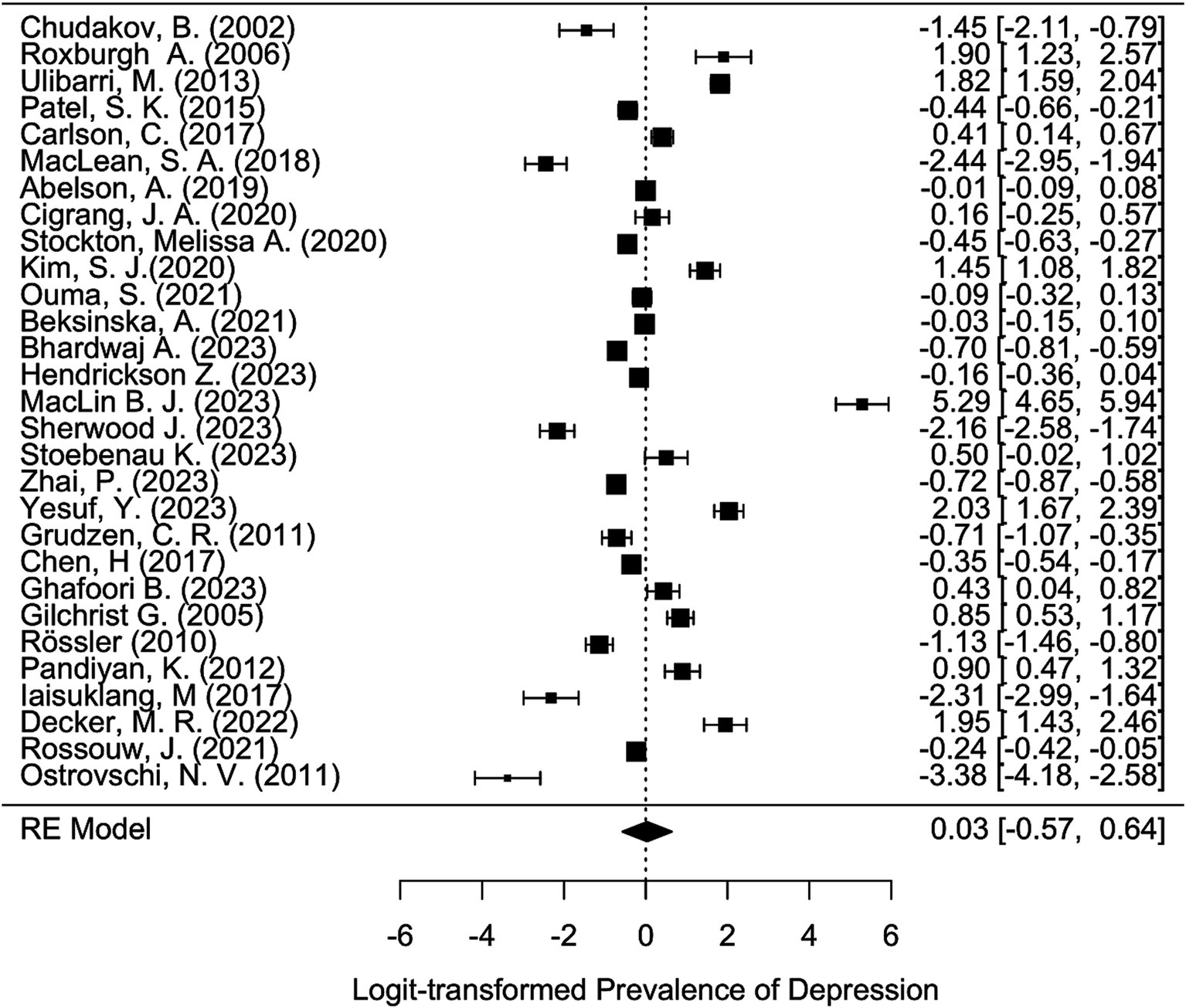

3.12 Depression 3.12.1 Overall meta-analysis findingsThe meta-analysis, based on 29 studies, utilized a random-effects model to account for variability across studies, indicating a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 99.51%, H2 = 203.65) in depression prevalence among sex workers. This heterogeneity is further quantified by the significant tau2 value (2.7128), suggesting substantial differences in depression rates across different contexts and populations. The overall effect size estimate was not significant (p = 0.9141). Please refer to Figure 5 for the forest plot.

留言 (0)