Repetitive head impact (RHI) exposure in sport is a topic of growing concern in clinical medicine, due to its potentially negative effects on long-term brain health (1–8). Participation in contact sport is a setting in which both RHIs and concussions or mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI) are common. American Football, in particular, represents the sport with the highest rate of male youth participation in United States and also accounts for the highest rate of reported concussive injuries among U.S. youth sports (9, 10). Historically, RHIs have been defined as subconcussive impacts to the head in which visible signs or symptoms of neurological dysfunction may not develop despite those impacts having the potential for neurological injury (11). However, the long-term negative effects of accumulated RHIs in sport have been previously reported (12) and associations between the accumulation of RHIs over a sport career and downstream neurodegenerative processes have been established (5).

Considering the associations with future neurodegenerative processes, it is critical that tools to measure brain alterations during sport participation are established in clinical practice. Brain alterations associated with functional or behavioral changes in young athletes who are experiencing frequent RHIs can be difficult to measure, especially given these athletes are often young, healthy, active, and a resilient population (13). Brain neuroimaging is a commonly used measure to detect alterations in functional and structural integrity associated with RHIs, despite its current limitations in cost and standardization (14). Functional connectivity between brain regions and networks, or the temporal correlation of regional alterations in the ratio of oxygenated, compared to deoxygenated cerebral blood flow, is measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and presents a sensitive method for detecting subtle changes in brain health (15). This is due in large part to fMRI’s power to map highly specific changes in regional coordination of neurometabolism in the absence of detectable structural damage to the brain (16).

Functional connections are commonly mapped across functional networks of the brain (17, 18). Naturally, the regions by which these networks are defined, demonstrate highly correlated functional connectivity, with respect to specific and unique brain functions (19). Two well defined networks, which have been studied extensively, using resting state-fMRI (rs-fMRI), for its sensitivity to changes in the brain function after head injuries of varying severity, is the Default Mode Network (DMN) and the Cognitive Control Network (CCN) (20–27) These network have been extensively studied and are sensitive to changes in the brain function after head injuries of varying severity (20–27). The default mode network (DMN) in particular has been extensively examined. Previous studies have demonstrated within-network hyperconnectivity of the DMN after a season of RHI exposure (28–37). However, hypoconnectivity after RHI accumulation has also been demonstrated in athletes (37). There have also been preliminary associations between alterations in within- and between-network connectivity resultant from RHIs and later-in-life neurodegenerative disease (38) following participation in football. However, this link remains largely understudied due to the lack of clarity surrounding network alterations after shorter periods of RHI exposure (i.e., across a single or multiple seasons).

One large confounding factor surrounding lifetime exposure to RHIs is player position on the field. Typically, in American football, players are considered speed (quarterbacks, wide receivers, linebackers, and defensive backs) and non-speed positions (defensive and offensive linemen), based on the role of the player on the field (39, 40). In American football, research using xPatch accelerometers has shown that there are differing rates of RHIs based on player positions (41). Speed positions often require players to engage in aggressive tackles or to be on the receiving end of such tackles, leading to a higher probability of moderate to high velocity head acceleration events (HAE) (42). These players also are often at higher risk for experiencing mTBI (43–45). In contrast, non-speed positions are more consistently involved in head-to-head contact at the line of scrimmage. These positions experience moderate to lower force HAE’s but at a higher frequency (41, 42) and typically have lower rates of mTBI (46). Additionally, work from our group has shown that serum concentrations of blood biomarkers glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neurofilament light chain (NFL) increased significantly over the course of a single collegiate football season and that the highest concentrations were in speed positions compared to non-speed positions (47).

Additionally, brain imaging studies have demonstrated football position-specific differences in various MRI metrics following exposure to RHIs. Specifically, defensive backs experienced more concussions and subsequent blood–brain barrier leaking than other positions (48), speed players exhibited a larger number of metabolic changes in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and M1 metabolites as compared with non-speed players (42), and speed players incurred mainly low cycle fatigue damage profiles of Tau deposition (49). Therefore, player position is an important confounder when analyzing the physiological consequences of exposure to RHIs in currently participating athletes.

Another confounding factor to exposure to RHIs is history of previous concussions (Cx). Cx has been associated with more severe symptom outcomes from subsequent concussions (50–52). Additionally, in regard to MRI work, some studies have found no difference in baseline functional connectivity in individuals with concussion history compared to individual without concussion history (24, 53). However, there is evidence that after a single competitive game involving exposure to RHIs, in this case rugby, those with a history of concussion showed greater alterations in DMN functional connectivity (31).

The overall goal of this study was to explore functional connectivity alterations both within the DMN and between the DMN and other brain regions using rs-fMRI over the course of a single season of collegiate American football. The DMN may show a large-scale, within-network hyperconnectivity response to a season of RHI exposure. However, it is still unclear how within-network or between network connectivity may change after a season of RHIs. Specifically, we aimed to (a) examine alterations in functional connectivity in the DMN from pre- to post-season in a large cohort of American collegiate football players, (b) examine alterations in functional connectivity between the DMN and other brain ROIs from pre- to post-season, and (c) identify if there is an effect of two major covariates, player position and concussion history, on these DMN related measures of functional connectivity.

2 Methods 2.1 Study design and settingThis prospective observational study was conducted at Penn State University, a public institution of learning and a participating member institution of the Big Ten Conference and NCAA Division I of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

2.2 Study population and proceduresDivision I NCAA collegiate American football athletes were recruited over 4 years (2015, 2019, 2021, 2022). Inclusion criteria for participation included 18 years or older and participation in intercollegiate athletic contact sport (American football). Exclusion criteria included the existence of a concurrent athletic injury that would preclude them from full participation during the season and contraindications to MRI (such as claustrophobia, metal orthodontic braces, and metal or cochlear implants). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Penn State University and all participants provided written informed consent.

All participants completed a pre-season interview which included demographic information, and medical and concussion history. Participants were contacted during the summer period of their sport (Figure 1A). At this time, they were taking part in standard non-contact summer strength and conditioning exercises, but not in any type of formal football practice and were not exposed to any head impacts or hitting. Prior to the start of preseason of each respective fall NCAA football season (when hitting practices begin), participants completed one MRI protocol which included a rs-fMRI sequence. During the fall football seasons, all participants included in the study participated in standard team activities, including football practices and games. Participants then completed a post-season MRI scan, which included a rs-fMRI sequence, within 7–14 days immediately following the conclusion of the Fall NCAA regular football season.

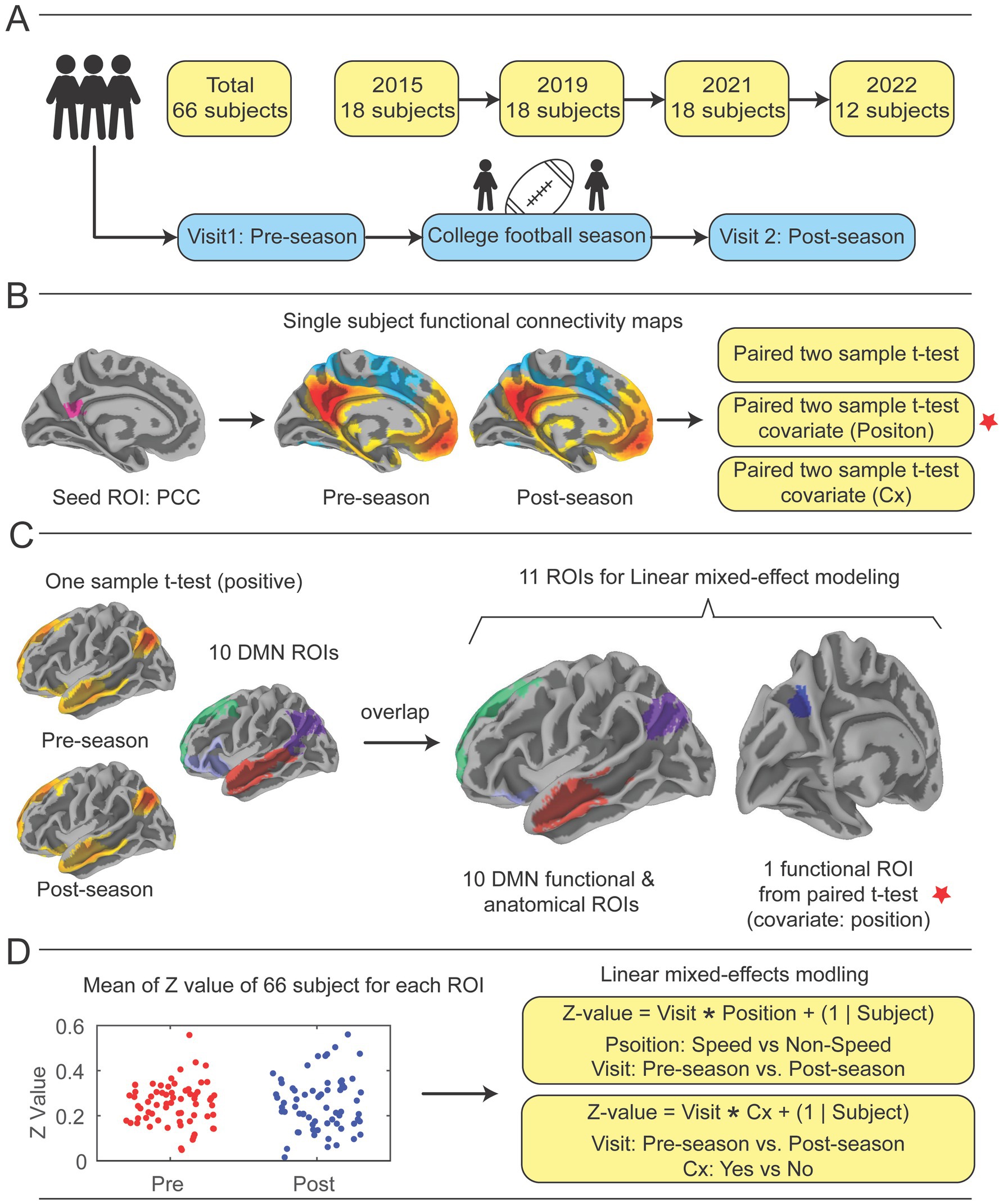

Figure 1. Study design. (A) Participants were recruited over the course of four collegiate football seasons. Each year, an identical imaging acquisition protocol was followed, which included a pre-season fMRI scan prior to any hitting practices beginning in the football preseason, the football season of note, and a post-season scan directly after the regular season ended. (B) The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) was pre-selected as a seed region, then correlation coefficients of mean time series of the PCC compared with all other brain voxels were calculated to demonstrate functional connectivity (FC) with the whole brain for pre-season and post-season scans (See Supplementary Figure 2A). Paired-sample t-tests were performed to identify significant differences in functional connectivity from pre- to post-season. Two covariates, player position and previous concussion history (Cx), were included in analysis. (C) Ten DMN ROIs were constructed by performing one-sample t-tests on pre- and post-season scans to identify regions that showed positively correlated mean time series with the PCC, then overlaying them upon 10 DMN ROIs from the Schaefer-Yeo atlas (58) (See Supplementary Figure 2B). 10 DMN ROIs and the one significant ROI in the left precuneus (LpCun) were used for linear mixed-effect modeling with covariates. (D) Utilizing linear mixed effect modeling with position and concussion history as covariates, the functional connectivity correlation coefficients for pre- and post-season were calculated, then changes from pre- to post-season were calculated by transforming the correlation coefficients to Fisher’s Z-scores to improve normality and subtracting pre-season Z-score from post-season Z-score (See Supplementary Figures 2–6). Cx = concussion.

2.3 MRI acquisitionAll imaging data were acquired using a 3 tesla Magnetom Prisma-Fit scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel head coil. The imaging protocol included the acquisition of T1-weighted structural images, resting-state blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional scans (rsfMRI) data, and field maps for distortion correction. Sagittal 3D magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) was acquired using the repetition time (TR) = 1700 ms, echo time (TE) = 1.77 ms, inversion time (TI) = 850 ms, flip angle = 9 degrees, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm x 256 mm, voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm, slices = 178, and scanning time = 3 min 34 s. Functional images were acquired using a 2D multiband echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequences (Release R016a, from the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR), University of Minnesota), with a TR = 2000 ms, TE = 35.8 ms, flip angle = 90 degrees, FOV = 192 mm x 192 mm, voxel size = 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm, slices = 72, multiband celebration factor = 3, and 300 repetition times (scanning duration of 10 min 10 s). To correct for susceptibility-induced distortions in the EPI images, field maps were acquired using a dual-echo gradient echo sequence (TEs = 4.92/7.38 ms). The individuals were instructed to lie awake with their eyes open. Of the original 117 participants recruited and consented at preseason, a total of 51 were removed prior to analysis as a result of increased body mass over the season. Twenty-eight of these removed were unable to complete their post-season scan due to increased body mass since preseason, that was incompatible with physically entering the scanner. An additional 23 participants’ data were removed due to motion artifact on their postseason scan, which was related to inability to comfortably fit within the standard 60 cm bore and 64-channel head coil used in this study.

2.4 MRI preprocessingThe preprocessing of the resting-state fMRI data was performed using fMRIPrep (version 23.1.0) (54), a standardized preprocessing pipeline for fMRI data. The preprocessing steps included motion estimation, slice timing correction, susceptibility distortion correction, co-registration of functional to anatomical images, and spatial normalization to the MNI152NLin2009cAsym standard space.

The smoothness and denoising procedure were performed by using AFNI (version 21.3.04). Spatial smoothing using gaussian kernel of 6 mm full-width half-maximum was implemented. To further reduce noise related to motion and physiological fluctuations, a general linear model (GLM) was used to perform additional denoising steps. Motion and physiological noise were addressed through nuisance regression calculated by fMRIPrep, which included six motion parameters (three translations and three rotations), their first derivatives, global signal regressor, and seven anatomical CompCor regressors (55, 56). A total of 20 regressors were included in the general linear model (GLM) to account for motion and physiological noise, ensuring that only the neural signals of interest remain. Frames that exceeded a threshold of 0.6 mm framewise displacement were annotated as motion outliers (57). The functional image data was bandpass filtered between 0.01 and 0.1 Hz.

2.5 Functional connectivity analysisFunctional connectivity analysis was performed by using AFNI (version 21.3.04). A seed region in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), (right and left pCunPCC_1, from the 400 parcels of the 7 networks defined by the Schaefer-Yeo atlas) (58) was used to create individual functional connectivity maps. The PCC was chosen due to its critical role in the default mode network (DMN), serving as a central hub of the DMN (59–61), and its previous applications in concussion studies (30, 62, 63). The mean time series from the PCC was extracted and correlated with the time series of all other voxels in the brain. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated and transformed to Fisher’s Z-scores to improve normality.

Group-level statistical analysis was conducted using two separate approaches. In the first analysis, voxel-wise paired t-test (Figure 1B) was performed to assess differences in connectivity patterns between pre-season and post-season by using AFNI’s 3dttest++. Player position and Cx were added as covariates for the pre-season and post-season test. The results of the paired t-tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using a cluster-based thresholding approach (AFNI’s Clustsim) with a significance level of p < 0.05 (uncorrected p < 0.001, cluster size = 134 voxels, voxel size = 2.00×2.00×2.00 mm^3) (Figure 1B).

In addition to the whole-brain seed-to-voxel analysis, a second ROI-based analysis was conducted to examine group differences in mean Z-values within 10 DMN ROIs and one ROI identified as significant from the paired t-tests (Figure 1B). In the analysis of 11 ROIs, including one ROI identified from the voxel-wise paired t-test and 10 atlas-based DMN ROIs, no correction for multiple comparisons was applied. This analysis was exploratory in nature, and results should be interpreted with caution. Future studies may benefit from applying correction methods, such as FDR or FWE, to address multiple testing. The 10 DMN ROIs were constructed by combining the 24 DMN ROIs from the Schaefer-Yeo atlas with group-clustered results derived from one-sample analyses.

First, 10 atlas-based DMN ROIs were derived from the 24 DMN ROIs in the Schaefer-Yeo atlas (spanning 7 networks and 100 regions) (58). These ROIs were constructed as follows (Supplementary Figure 1): (1) left temporal (Default_Temp_1 + Default_Temp_2); (2) left parietal (Default_Par_1 + Default_Par_2); (3) left prefrontal cortex PFCdPFCm (Default_PFC_1 + Default_PFC_2); (4) left PFCv (Default_PFC_3 + Default_PFC_4 + Default_PFC_5 + Default_PFC_6 + Default_PFC_7); (5) left pCuPCC (Default_pCunPCC_1 + Default_pCunPCC_2); (6) right parietal PAR (Default_Par_1); (7) right temporal (Default_Temp_1 + Default_Temp_2 + Default_Temp_3); (8) right PFCv (Default_PFCv_1 + Default_PFCv_2); (9) right PFCdPFCm (Default_ PFCdPFCm _1 + Default_ PFCdPFCm _2 + Default_ PFCdPFCm _3); (10) right pCuPCC (Default_pCunPCC_1 + Default_pCunPCC_2). Second, separate one-sample t-tests were performed on pre-season and post-season scans to identify regions positively correlated with the PCC, using a threshold of corrected p < 0.05 (based on uncorrected p < 0.001 with a cluster size of 134 voxels). These analyses highlighted well-established DMN areas showing positive correlations with the PCC during task-negative states. Third, the positive regions from the one-sample t-tests for pre-season and post-season scans were overlapped, ensuring that the resultant mask regions were significantly positively correlated with the PCC during both visits. Finally, the 10 atlas DMN ROIs were overlaid with the positive clustered regions to produce the final 10 DMN ROIs, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. Additionally, an extra ROI in the left precuneus (LpCun) was created based on a significant region identified in the paired t-test (voxel count: 202; volume: 1616 mm3; MNI peak coordinates: −12.5, −70.5, 35.5) (Figure 1C, marked by red stars).

Group differences in functional connectivity within these ROIs were assessed using an uncorrected linear mixed-effects models implemented in MATLAB (R2022b) The linear mixed effect models were not corrected using not corrected using FDR or FWE methods commonly applied in ROI-based studies, since they acted as a second measure of accuracy to confirm the seed-to-whole-brain voxel analysis, which had already been corrected using the ClustSim method. Two models were used to test group differences (Figure 1D). The first model was defined as:

Z−value=Visit∗Position+1|SubjectWhere Position indicates Speed vs. Non-Speed and Visit indicates Pre-season vs. Post-season.

The second model was defined as:

Z−value=Visit∗Cx−History+1|SubjectWhere Cx indicates History of Yes vs. History of No and Visit indicates Pre-season vs. Post-season (Figure 1D).

3 Results 3.1 Demographic and outcome characteristics117 players consented into the study over the four seasons. After removing participants with missing data (n = 28) or individuals with non-useable fMRI sequences (n = 23), 66 participants were included in analyses. These individuals were a mean age of 20.55 ± 1.52 years, 100% male, and had played football for a mean of 10.84 ± 4.85 years (Table 1). 33% reported at least one previously diagnosed concussion and 48% were considered speed position players. By season, participants did not differ significantly in any demographic factor.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

3.2 Whole-brain, voxel-wise analysis 3.2.1 Seed-based mappingThe seed region PCC demonstrated significant effect of player position in the whole brain voxel-wise paired t-tests. Threshold of corrected p < 0.05 (based on uncorrected p < 0.001 with a cluster size of 134 voxels) (Supplementary Figure 1). One additional voxel cluster, the LpCun demonstrated significant connectivity with the PCC from the paired t-tests (p < 0.01). The results of the ROI analysis are presented as exploratory findings and have not been corrected for multiple comparisons. While this approach provides additional insights, it is important to note that these findings should be validated in future studies using stricter correction methods.

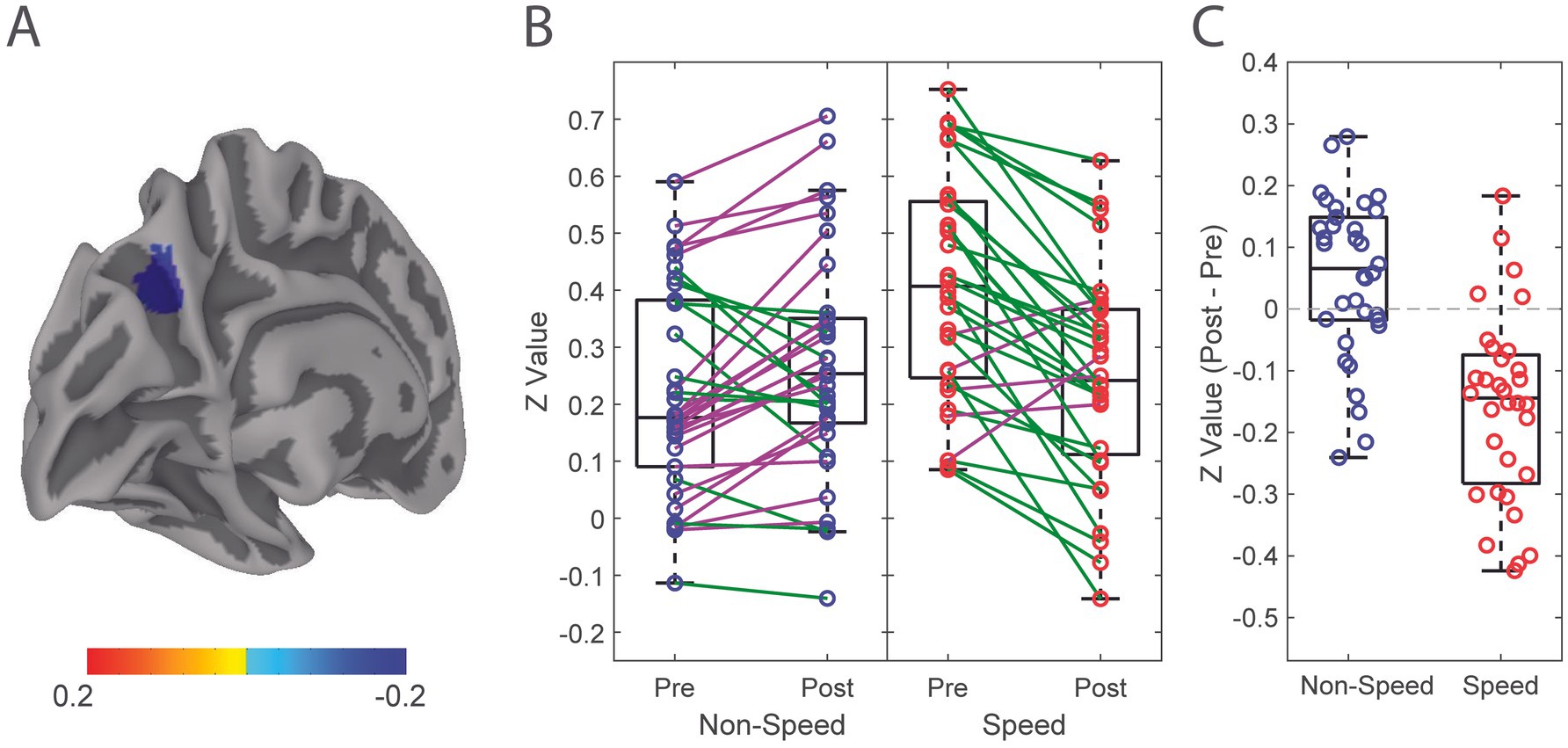

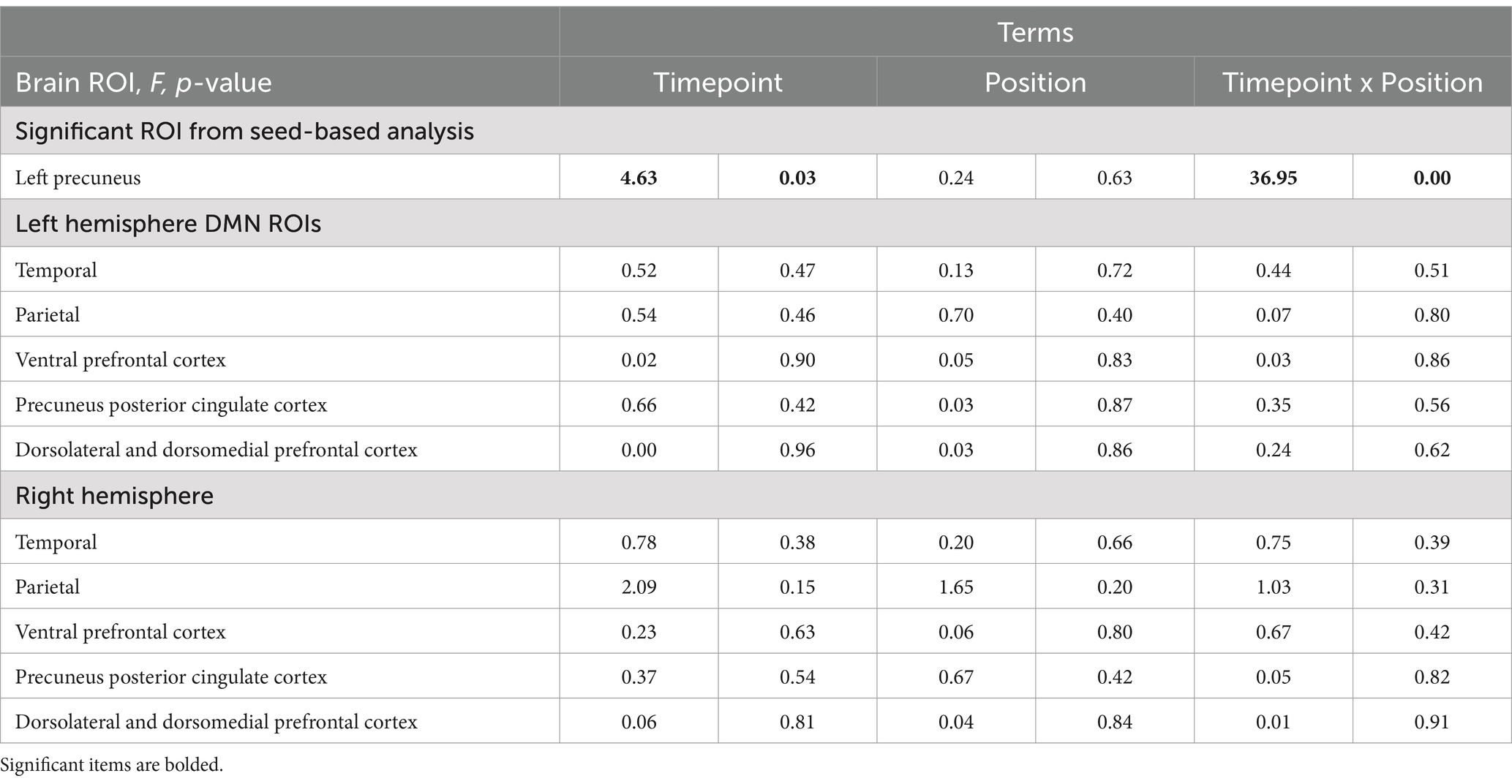

3.2.2 Linear mixed effects modelBy player position, there was a significant effect of time (F (1, 132) = 4.63, p = 0.03) and time by position interaction (F (1, 132) = 36.95, p < 0.001) where speed players had decreased functional connectivity of the LpCun from pre-season to post-season compared to non-speed players (Figure 2). When examining alterations from pre- to post-season in functional connectivity of the LpCun by Cx, there were no significant findings (Table 2).

Figure 2. Alteration in functional connectivity from pre-season to post-season of the Left Precuneus in Speed and Non-Speed players. (A) Linear mixed effect modeling was used to determine significant differences in functional connectivity correlation of the LpCun from pre-season to post-season, including position type and concussion history (Cx) as a covariate. (B) Directionality of alterations in functional connectivity from pre-season to post-season are illustrated in Speed (red) and Non-Speed (blue) players. Positive trend lines indicate increased coherence from pre-season to post-season, while negative trend lines indicated a decrease. (C) Difference in functional connectivity between Speed and Non-speed players from pre-season to post-season are further demonstrated using box-and-whisker plots. Negative values indicate decreases in functional connectivity from pre-season to post-season, while positive values indicate increases.

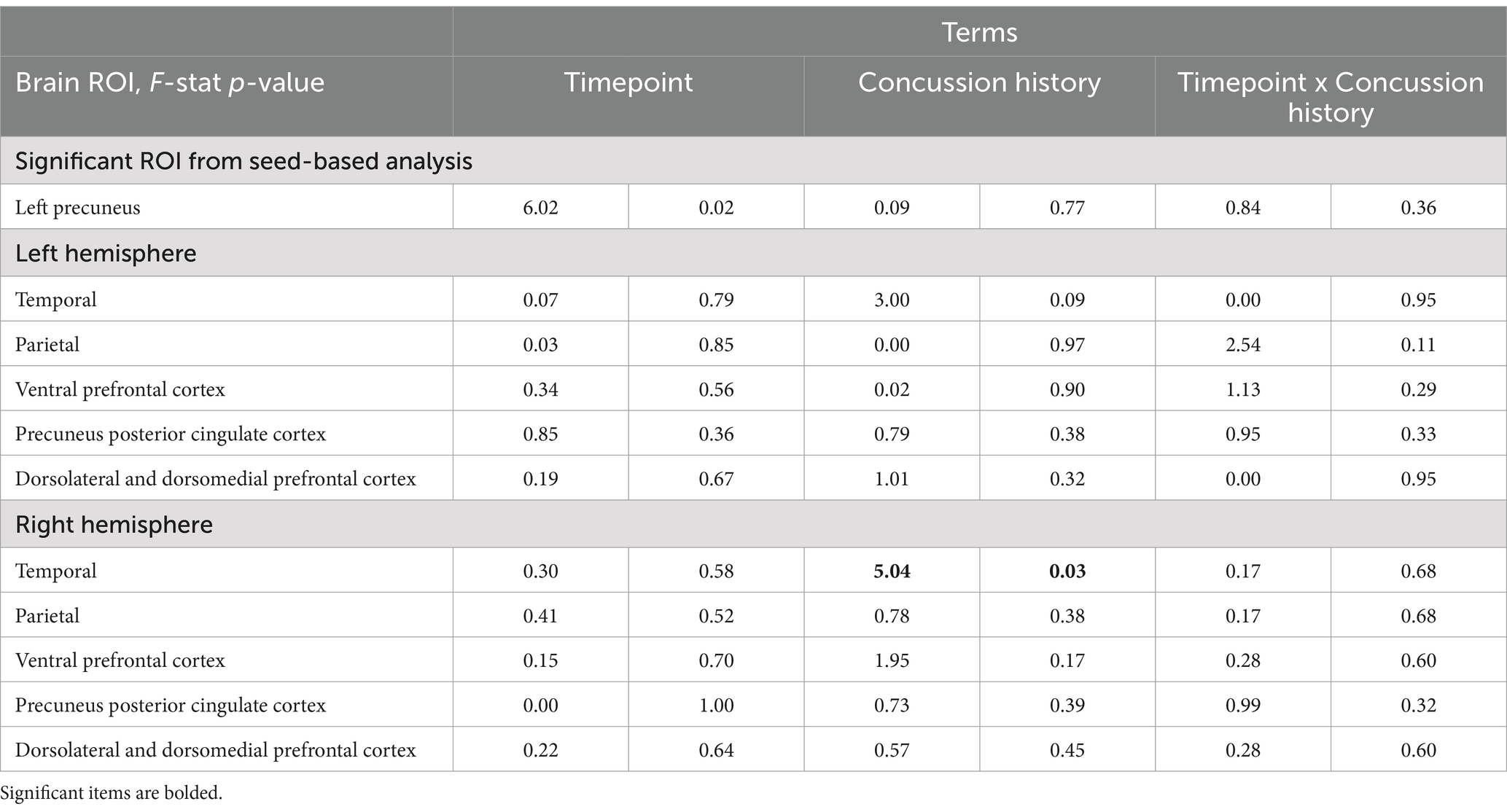

Table 2. Linear mixed-effect model of DMN ROIs: Timepoint x Concussion History.

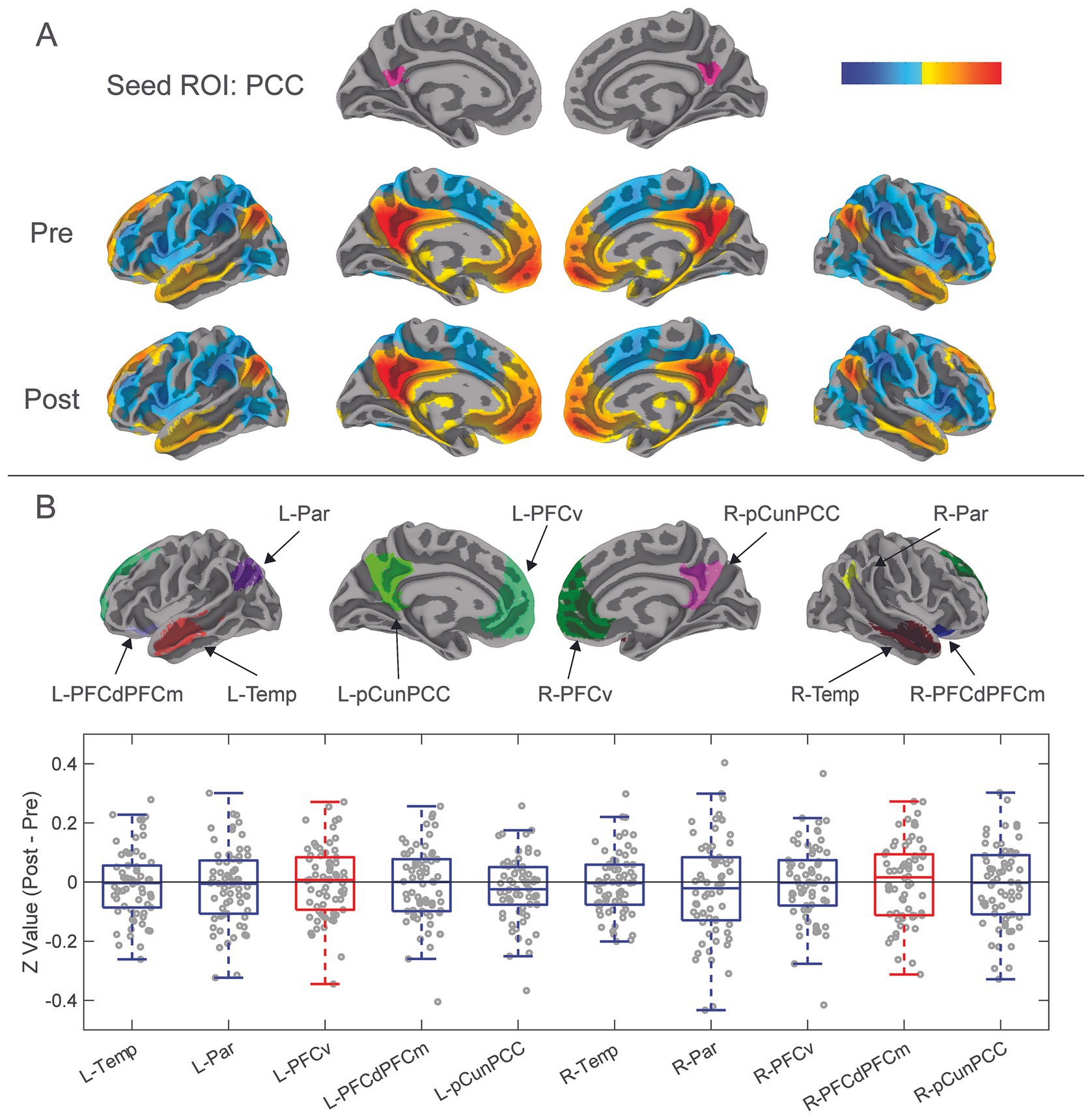

3.3 Ten default mode network regions of interestFunctional connectivity changes from pre-season to post-season in ten DMN ROIs were calculated (Figure 3) (Supplementary Figure 2). There were no significant differences in functional connectivity from pre- to post-season within any of these ROIs (Figure 3B). Visually, changes in functional connectivity across the season (post-season minus pre-season) between the PCC and the 10 DMN ROIs demonstrated both hypoconnectivity (8 of the ROIs) and hyperconnectivity (2 of the ROIs).

Figure 3. Results from functional connectivity analysis 10 DMN ROIs. (A) The PCC was previously isolated as a seed ROI for functional connectivity analysis with the whole brain. Correlation coefficients of mean time series of the PCC compared with all other brain voxels were calculated to demonstrate functional connectivity between the PCC and whole brain for pre-season and post-season scans. Red-yellow areas represent voxels that demonstrated positive correlation coefficients, while blue areas represent negative correlation coefficients. (B) Ten additional DMN ROIs were constructed from the combination of the DMN ROIs of the Schaefer-Yeo atlas and group clustered results from one sample t-tests (See Figure 1C; Supplementary Figure 1). DMN ROIs included left and right: temporal, parietal, ventral prefrontal cortex, dorsolateral and dorsomedial prefrontal cortices, and precuneus-posterior cingulate cortex. Difference in pre-season to post-season functional connectivity of the ten DMN ROIs was calculated by transforming their mean time series correlation coefficients to Fisher’s Z-values, then subtracted pre-season from post-season. These pre- to post-season changes are represented with the box-and-whisker plot showing Z-values of paired sample t-tests of post-season minus pre-season functional connectivity of the 10 DMN ROIs. Blue boxes show decreases in hypoconnectivity (decreased functional connectivity) from pre-season to post-season, while Red boxes show hyperconnectivity (increased functional connectivity) from pre-season to post-season.

When examining the influence of player position and Cx on changes in functional connectivity in DMH ROIs, linear mixed models were used to examine functional connectivity alterations from pre- to post-season. There were no significant differences in functional connectivity from pre- to post-season in any of the DMN ROIs by player position (Table 3; Supplementary Figures 3, 4). Concussion history did have a signification effect on functional connectivity, specifically in the right temporal ROI of the DMN (F (1,132) = 5.04, p = 0.03; Table 2) However, there was no significant effect of timepoint.

Table 3. Linear mixed-effect model of DMN ROIs: Timepoint x Position.

4 DiscussionIn this observational study, we examined changes of functional connectivity in a relevant and well-documented neural network, the Default Mode Network. Several key findings were highlighted in this study. First, functional connectivity within the functional ROIs of the DMN, remained largely unchanged from pre-season to post-season, a period during which participants were exposed to high accumulation of RHIs. Second, the inclusion of player position and concussion history as covariates had varying effects on functional connectivity changes from pre- to post-season, with the most tangible finding being the significant decrease in functional connectivity of the LpCun in Speed, but not Non-Speed players.

4.1 Ten default mode network regions of interestThere were no significant alterations in functional connectivity observed from pre- to post-season within the 10 DMN ROIs. This finding was contradictory to our initial hypothesis, as much of the literature has identified the DMN as a network that is susceptible to alterations in functional connectivity after RHI (21, 28, 30, 35). The findings here showed both non-significant hyper- and hypo-connectivity across the season in different ROIs. This finding, paired with inconsistencies in the directionality of DMN functional connectivity changes in studies that did show alterations, may suggest that the DMN is less susceptible to consistent specific alterations after RHI than it is after reported mTBI. Additionally, other networks may be more reliable targets for acquiring consistent results with respect to alterations after RHI.

With respect to the finding of significant group difference in functional connectivity of the right temporal ROI of the DMN, there was a significant effect of concussion history, but no significant effect of timepoint. There are mixed findings in the literature surrounding alterations in functional connectivity as a result of concussion history, with some studies reporting no differences (24, 64) and others reporting altered baseline functional connectivity (65, 66) in those with a history of concussion. However, the mechanism through which functional connectivity alterations occurred in the unilateral temporal region specifically is unknown and may be explored further in future research.

4.2 Single season functional connectivity changes of the LpCun are dependent on player positionPlayer position was associated with alterations in functional connectivity from pre-season to post-season. Speed players demonstrated a decrease in functional connectivity from pre-season to post-season, while non-speed players showed no differences. There are biomechanical differences in the magnitude, location, and frequency of RHIs between the two position groups. Speed players receive less RHIs, with greater average force per RHI, and at varying locations across the helmet, however Non-speed players tend to receive more RHIs with less average force per RHI, and localized RHIs to the crown and forehead, a location associated with lower neural tissue strain (40, 47, 67). This finding may suggest that, as a result of the different biomechanical signatures of the RHIs, speed players may be at greater risk for alterations in brain health after a single season, compared with non-speed players. This imaging finding, although mechanistically unique, is complimentary to previous work from our group that showed significantly higher serum concentrations of TBI biomarkers in Speed, compared to Non-speed players after a single collegiate football season, regardless of whether a concussion was incurred during a season (47).

The precuneus is a region integrated with both the DMN (68, 69) and CCN (69–71), and because the precuneus has been shown to play a major role in integrating high level brain functions such as attention (72, 73) and visual and auditory memory (74), this finding may suggest a greater risk of decreased capacity of these functions. However, this finding should be carefully considered in context as other research shows that non-speed players are at greatest risk of early neurodegenerative processes (75). It may be that the timeframe being considered is critical when examining player position. The overall accumulation of RHIs over a lifetime is a known risk for neurodegenerative disease (5). However, alterations in short-term (i.e., over a single season) outcomes may be more affected by higher impact RHIs, like those received in speed positions. The specific connection between the LpCun and PCC should be of particular note for future examination of functional connectivity alterations after RHIs.

Cx had no relationship with alterations in functional connectivity of the LpCun from pre-season to post-season. This finding is consistent with our previous TBI biomarker work in the same population (76). Of note, however, Cx can influence symptom outcomes. The number of previous concussions and the time since last concussion can affect severity and symptom profile of future concussions (50–52). Additionally, concussion history has long been implicated as a risk factor for early onset of neurodegenerative processes (77). However, there are conflicting results about the effect of previous concussion on outcomes of RHI accumulation. Several studies have shown no neural signatures of alterations in functional connectivity related to concussion history in young or middle-aged individuals (24, 53), while our group has previously demonstrated clear concussion history-dependent alterations in connectivity after a single game of RHI exposure in rugby, in the DMN (31). Guidelines developed at the first Safety in College Football Summit in 2014, which enforced a decrease in opportunities for RHI accumulation over the calendar year may have played a role in the lack of functional connectivity alterations related to concussion history (78). Perhaps the lack of effect of concussion history in this study is due to the relative good health and fitness of our younger population (13). It appears that concussion history may act as a risk factor for alterations in brain health later in life but may not be a fully conclusive marker of subtle early life deficits, particularly in otherwise healthy populations.

4.3 LimitationsThis study was subject to several inherent limitations, including those related to sample characteristics, imaging acquisition, brain parcellation, and quantification of covariates. Our sample consisted exclusively of male participants as a function of the sport of interest (American football). However, the omission of female participants does detract from the generalizability of our findings as we cannot include sex as a biological covariate. Additionally, due to the altered body composition (increased mass) of our sample population, neuroimaging acquisition presented an administrative challenge to fit particular individuals comfortably in the 3 T Tesla scanner at postseason. Thus, we were forced to remove participants as a result of incomplete or unsuccessful postseason scans, related to inability to fit in the scanner and movement artifact, respectively. With respect to brain map parcellation, the use of the Schaefer 400 atlas comes with inherent pitfalls due to its universality. However, this blanket application of a single atlas was accounted for by overlaying individual functional connectivity maps from the seed-based method. Given the focus on cortico-cortical connectivity, we also recognize that our volume-based approach offers imperfect localization of function to precise cortical anatomy. Furthermore, our two covariates of interest, position and Cx, were imperfect for different reasons. Position, while a validated determinant of biomechanical characteristics of RHI exposure type, does not provide as comprehensive a measure of RHI accumulation as would helmet accelerometer data. Cx was collected using a self-report questionnaire, thus may not have been a completely valid record of medically diagnosed concussions for all participants. It is important to note that none of the participants included in this study were diagnosed with a concussion by medical personnel during the course of the season. Additionally in contact sports, concussion often goes undiagnosed, thus this measure of Cx may inherently lack some degree of accuracy.

5 ConclusionIn a 4-season cohort of collegiate American football players, functional connectivity of specific regions and networks are affected differently after a single season of exposure to RHIs. Player position is an important covariate to consider when assessing functional connectivity alterations, especially in the LpCun. There were no significant alterations in the 10 DMN ROIs across the season, despite ROIs showing either hyper-connectivity or hypo-connectivity from pre- to post-season. These findings suggest that brain alterations, as assessed by fMRI, after a single season of RHIs are possible and certain players may be more susceptible to these changes.

5.1 Transparency, rigor and reproducibility summaryA minimum sample size of 32 participants, with a maximum sample of size of 120, was planned based on availability of participants from the sample population, a highly specific player position types from a Division-1 American football team, during a specific annual time point. A maximum sample size of 120 participants was planned based upon funding capabilities. A sample size of 117 participants were initially screened, and useable imaging data were obtained and analyzed from 66. Imaging data were obtained between August 2015 and December 2022. Imaging acquisition and analyses were performed by team members blinded to relevant characteristics of the participants, and clinical outcomes were assessed by team members blinded to imaging results. All equipment and software used to perform imaging and preprocessing are widely available from commercial sources. Statistical analysis and/or review was performed by Bai, X., who holds the title of Technical Co-Director of the Penn State University Social, Life, and Engineering Sciences Imaging Center. All equipment and software used to perform imaging and preprocessing are widely available from commercial sources. No replication or external validation studies have been performed or are planned/ongoing at this time to our knowledge.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Penn State University Central Applied Tracking System Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsOG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XB: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JK: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. WS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Collegiate Athletics Association [OSP 209924]. AEW acknowledges support from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [T32NS043126]. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to funding, intellectual property, or otherwise.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the staff at the Social, Life, and Engineering Sciences Imaging Center at the Pennsylvania State University for the assistance in imaging data acquisition. Additional thanks to Penn State Athletics and Penn State Sports Medicine for their assistance with this project.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1511915/full#supplementary-material

References1. Bazarian, JJ, Zhu, T, Zhong, J, Janigro, D, Rozen, E, Roberts, A, et al. Persistent, long-term cerebral white matter changes after sports-related repetitive head impacts. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e94734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094734

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Di Battista, AP, Rhind, SG, Richards, D, Churchill, N, Baker, AJ, and Hutchison, MG. Altered blood biomarker profiles in athletes with a history of repetitive head impacts. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0159929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159929

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. McAlister, KL, Mack, WJ, Bir, C, Baron, DA, Som, C, Li, K, et al. Longitudinal, prospective study of head impacts in male high school football players. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0291374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291374

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. McKee, AC, Cantu, RC, Nowinski, CJ, Hedley-Whyte, ET, Gavett, BE, Budson, AE, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. (2009) 68:709–35. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. McKee, AC, Stein, TD, Nowinski, CJ, Stern, RA, Daneshvar, DH, Alvarez, VE, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain. (2013) 136:43–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws307

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Strauss, SB, Fleysher, R, Ifrah, C, Hunter, LE, Ye, K, Lipton, RB, et al. Framing potential for adverse effects of repetitive subconcussive impacts in soccer in the context of athlete and non-athlete controls. Brain Imaging Behav. (2021) 15:882–95. doi: 10.1007/s11682-020-00297-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Mueller, FO, and Colgate, B. Annual survey of football injury research 1931–2010. The National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research (2021)

10. O’Connor, KL, Baker, MM, Dalton, SL, Dompier, TP, Broglio, SP, and Kerr, ZY. Epidemiology of sport-related concussions in high school athletes: National Athletic Treatment, injury and outcomes network (NATION), 2011-2012 through 2013-2014. J Athl Train. (2017) 52:175–85. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.15

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Walter, A, Herrold, AA, Gallagher, VT, Lee, R, Scaramuzzo, M, Bream, T, et al. KIAA0319 genotype predicts the number of past concussions in a division I football team: a pilot study. J Neurotrauma. (2019) 36:1115–24. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5622

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Marek, S, Tervo-Clemmens, B, Calabro, FJ, Montez, DF, Kay, BP, Hatoum, AS, et al. Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature. (2022) 603:654–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04492-9

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Rogers, BP, Morgan, VL, Newton, AT, and Gore, JC. Assessing functional connectivity in the human brain by FMRI. Magn Reson Imaging. (2007) 25:1347–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.007

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. van den Heuvel, MP, and Hulshoff Pol, HE. Exploring the brain network: a review on resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2010) 20:519–34. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.03.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Abbas, K, Shenk, TE, Poole, VN, Breedlove, EL, Leverenz, LJ, Nauman, EA, et al. Alteration of default mode network in high school football athletes due to repetitive subconcussive mild traumatic brain injury: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Connect. (2015) 5:91–101. doi: 10.1089/brain.2014.0279

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Abdul Rahman, MR, Abd Hamid, AI, Noh, NA, Omar, H, Chai, WJ, Idris, Z, et al. Alteration in the functional Organization of the Default Mode Network Following Closed non-severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:833320. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.833320

留言 (0)