Musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders are the leading causes of disability and functional limitations in daily life and work participation worldwide (1). The impact on public health is considerable (2), requiring new ways of managing these conditions (3).

Pain is the cardinal symptom of MSK disorders and represents a challenge in occupational settings, serving as primary reason for increased medical expenditures tied to disability and compromised quality of life of workers (4). In a European context, MSK pain is responsible for more than half of work-absenteeism (5). This negative effect demonstrates that the repercussions of MSK pain extend beyond individual well-being, bearing significant economic consequences for employees, employers, and society at large (5, 6).

Multiple factors such as older age, unhealthy lifestyle, compromised mental health, comorbidities, and the presence of MSK symptoms contribute to the development and persistence of MSK pain, limiting daily activities and work capacity (3). There are also risk factors for MSK pain specific to the occupational setting (7), including physical work demands such as manual handling or awkward postures, as well as organizational factors related to an unhelpful workplace design, and poor job satisfaction (8). The interconnection of these factors underscores the multifaceted nature of work-related MSK pain and emphasizes the importance of a broad assessment of this condition.

Identifying modifiable risk factors is key to estimate the likely trajectory of a health condition, thus aiding healthcare professionals in making informed management decisions (9, 10). Moreover, an early identification of potential risk factors can aid in preventing the onset and persistence of chronic MSK pain (10, 11). While previous research has predominantly explored the correlation between self-reported work ability and return to work in rehabilitation settings, there is a urgent need for tools that comprehensively assess biopsychosocial factors associated with MSK pain in the occupational settings (12). Accurate and transparent information regarding workers’ conditions is essential for devising effective rehabilitation strategies (13, 14) and facilitating a successful return to work (15–17). The Prevent for Work questionnaire (P4Wq) builds on MSK pain within a biopsychosocial framework (18).

The P4Wq was developed under a European initiative between Italian, Spanish and Danish institutions aiming to develop a self-administered questionnaire that assesses factors related to the development of work-related MSK pain (18). While its adoption can facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of work-related MSK pain and aid in devising effective prevention and management, objective data on its adequate psychometric properties only exist in an Italian working population (19). The original Italian version provided a concise measure of risk factors for work-related back disorders that have demonstrated good content validity, construct validity, internal consistency reliability and high face validity. To expand this to other languages, it is important to translate and culturally adapt the questionnaire to other languages. In the future, this will allow for a comparison of work-related MSK pain in other populations of workers from different European countries.

This study aimed to cross-culturally adapt the original Italian version of the P4Wq into European-Spanish, as well as evaluate its psychometric properties (i.e., face validity, structural validity, internal consistency, construct validity, floor and ceiling effects, reliability, and measurement error) in workers.

2 Materials and methods 2.1 Study designThis study was set up in two phases: (i) a cross-cultural adaptation phase and (ii) a validation phase. The present study was conducted in consensus with the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) study design checklist (20). The study was conducted per the Helsinki Declaration and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at San Jorge University (N01-20/21). All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study.

2.2 Study settings and participantsParticipants were among active workers recruited in February–May 2021 from institutions in the autonomous community of Aragon (Spain), as part of the Prevent4Work project (4). Inclusion criteria established were (a) age between 18 and 65 years old, (b) ability to read and speak Spanish, and (c) one or more year of employment in the current position. People with (a) previous history of major surgery for a MSK disorder, (b) diagnosis of any persistent painful condition of specific pathology (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, spinal stenosis), (c) habitual intake of antidepressants, and (d) medial history involving cancer, brain or spinal cord injury, or psychiatric and neurological disorders, were excluded. Notwithstanding the prior briefing about the criteria, each participant completed a self-reported checklist at the initiation of the questionnaire series to verify their compliance with the outlined selection criteria.

2.3 Cross-cultural adaptationThe translation and cross-cultural adaption was done following forward-and back-translation (21) from Italian into European-Spanish. This process involved two proficient translators, one with a medical background, who were native speakers of European-Spanish. They independently generated two translations of the original questionnaire from Italian to European-Spanish. Subsequently, these translations were compared and analyzed to detect any inconsistencies between them. These inconsistencies in the translations were discussed until a consensus on the final version was reached. In case of disagreements, a member of the research group (PB-L) was consulted to reach an agreement. Following this, a backward translation of the synthesized version was carried out from Spanish back to Italian by two independent native Italian translators, who were not previously familiar with the original Italian version of the questionnaire. Subsequently, an expert committee composed of the authors, convened to assess the final version of the translated questionnaire. The committee reviewed the entire forward-and back-translation process, specifically examining any potential inconsistencies and ensuring that the questions were comprehensible across the target populations.

2.4 Pilot study for face-validityAfter the creation of the prefinal versions of the P4Wq, a group of thirty volunteer workers participated in pilot testing to assess its face validity. Each participant completed the questionnaire and subsequently underwent an interview, where the focus was on examining their understanding of each questionnaire item and the available responses. To quantify the face validity, two distinct 5-point Likert scales were employed to evaluate the clarity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire items. The face validity index was determined as the average value of the Likert scales, converted to a scale ranging from 0 (total lack of clarity or comprehension) to 100 (complete clarity or comprehension) (22); with a score > 80% considered satisfactory (23). Furthermore, completion time was registered.

2.5 Validity studyParticipants completed a paper version of the Spanish version of the P4Wq, a questionnaire designed to assesses biopsychosocial factors related to the development of work-related MSK pain. The P4Wq includes sociodemographic data, disabling pain prevalence, and potential risk factors such as job satisfaction, mental stress, kinesiophobia, catastrophizing, and physical stress, with responses scored on a 5-point Likert scale where higher scores indicate greater risk. The Spanish version of the EuroQol Five-Dimensions Five-Levels levels (EQ-5D-5L) (24, 25) was used to evaluate general health status across five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain-discomfort, and anxiety-depression) using a 5-point scale, alongside a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) for overall health where higher scores represent better health. Lastly, the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (26, 27) was used to measure disability related to spinal disorders through 10 dimensions of daily activities, scored on a 6-point scale, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of disability. A detailed description of the questionnaires is provided in Supplementary Table A.

A subset of 50 individuals was randomly chosen to undergo a test–retest assessment of the Spanish version of the P4Wq after a 2-week interval, aimed at evaluating the test–retest reliability and measurement error. During this stage, all participants were asked to fill out a checklist to ensure the consistency of their responses over the interim period. This checklist included questions regarding the occurrence of any new episodes of disabling MSK pain, instances of sick leave, or the reception of physical or psychological treatment.

2.6 Hypotheses testing for construct validityAs contemplated in the COSMIN recommendations, construct validity was assessed by means of convergent validity and known-groups validity (20). Following a similar methodology to the original development of the P4Wq to evaluate convergent validity, we hypothesized that a significant moderate correlation would exist between the total scores of the Spanish version of the P4Wq, and existing measures of quality of life (i.e., the visual analogue scale of the EQ-5D-5L) and disability (i.e., the ODI). Furthermore, as the P4Wq was intended to measure risk factors for work-related MSK disorders in the spine (neck, thoracic, and low back regions), data from participants reporting 12 months prevalence of disabling spinal MSK pain were extracted for further analysis (i.e., disabling spinal pain vs. no disabling spinal pain). Disabling pain refers to pain that has limited daily activities (28). We hypothesized that workers with a history of disabling spinal pain would present higher scores in the P4Work compared to those workers classified as having no disabling spinal pain.

2.7 Sample sizeThe COSMIN recommendations determined the sample size for calculating the confirmatory factor analysis, which is considered an excellent sample size when it consists of 7 times the number of items (i.e., 140 participants) (20). However, after accounting for up to 10% of ineligible questionnaires, a sample size of 154 participants was intended. In fact, a sample size higher or equal to 100 participants was considered sufficient for testing internal consistency, construct validity or test–retest reliability, while was considered adequate if higher or equal to 50 participants (20).

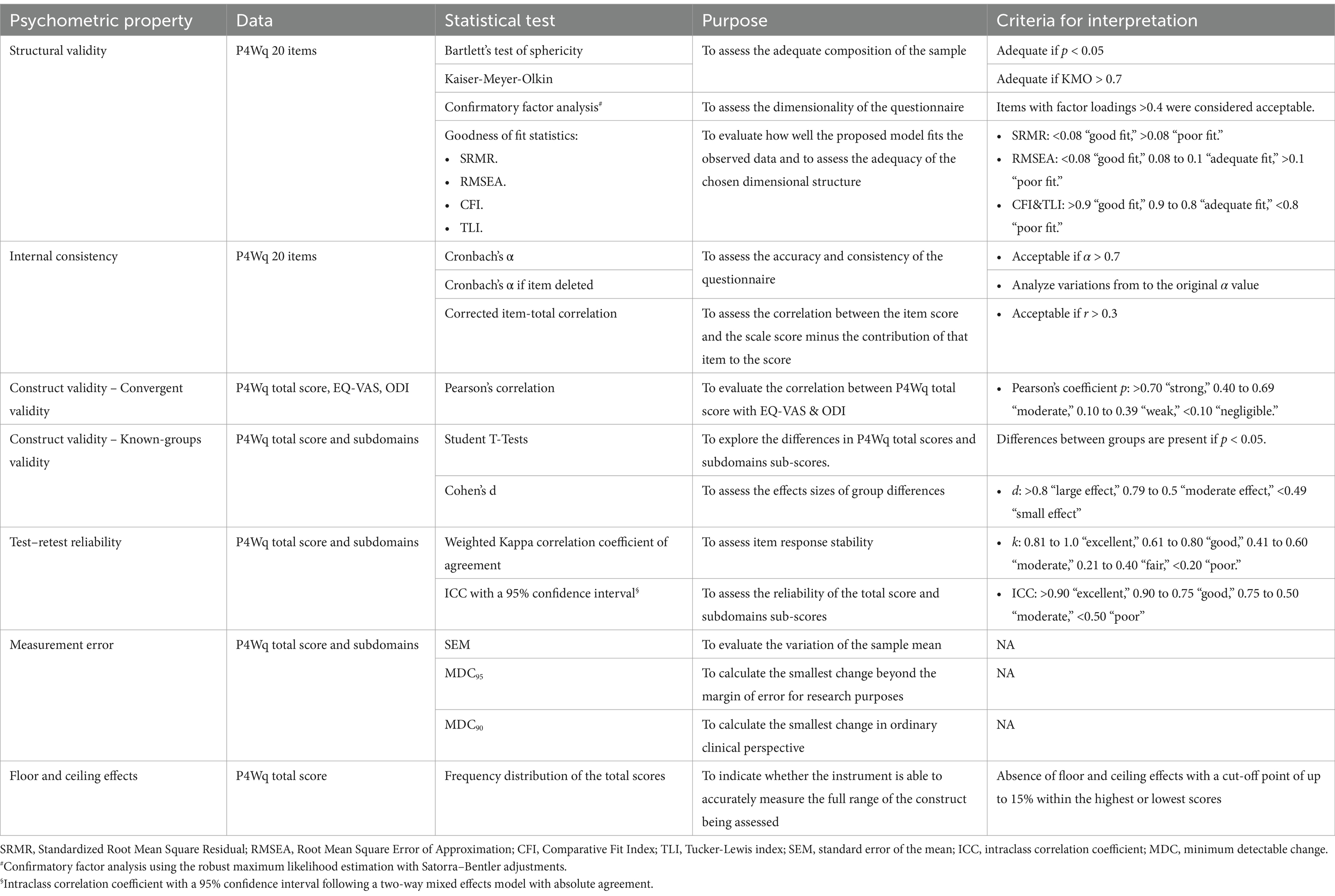

2.8 Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.28 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), except for the confirmatory factor analysis, using STATA v.18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Participant data containing blank items in the P4Wq were excluded from the analysis. Mardia’s test was used to determine whether P4Wq data were multivariate normally distributed. The results were expressed as mean (± standard deviation (SD)), and/or 95% confidence intervals (CI). The level of significance was set at p-value <0.05. The detailed description of the statistical tests used in the present study is depicted in Table 1, for: (1) structural validity (29–33); (2) internal consistency (34); (3) construct validity by means of convergent validity (35), and known groups validity (36); (4) test–retest reliability (37, 38); (5) measurement error (39); and (6) floor and ceiling effects (40). Subgroup analyses were conducted for sex, age category (<45 years or ≥ 45 years) and work type (office, healthcare, blue-collar) using linear regression models and independent T-Student or ANOVA with Bonferroni correction as post hoc test.

Table 1. Statistical tests used.

3 Results 3.1 Cross-cultural adaptation and face-validity processesThere were no considerable differences between the forward translations of the original Italian version of the P4Wq into European-Spanish, except for minor variations in word order that did not alter the meaning of the items. Similarly, there were no major discrepancies between the backward translations, preserving the meaning of the original version.

Thirty workers in Spain (40.7 ± 9.2 years, 50% females) completed the prefinal version of the P4Wq. The median time to fill the P4Wq was 4 min [IQR 3–5] for the Spanish version. The face validity index was 93.8%. No clarity and comprehension difficulties were reported for the Spanish with all items scored 4 or 5 (i.e., clear or very clear). No further changes were implemented, and the final version of the P4Wq in European-Spanish is presented in the Supplementary material.

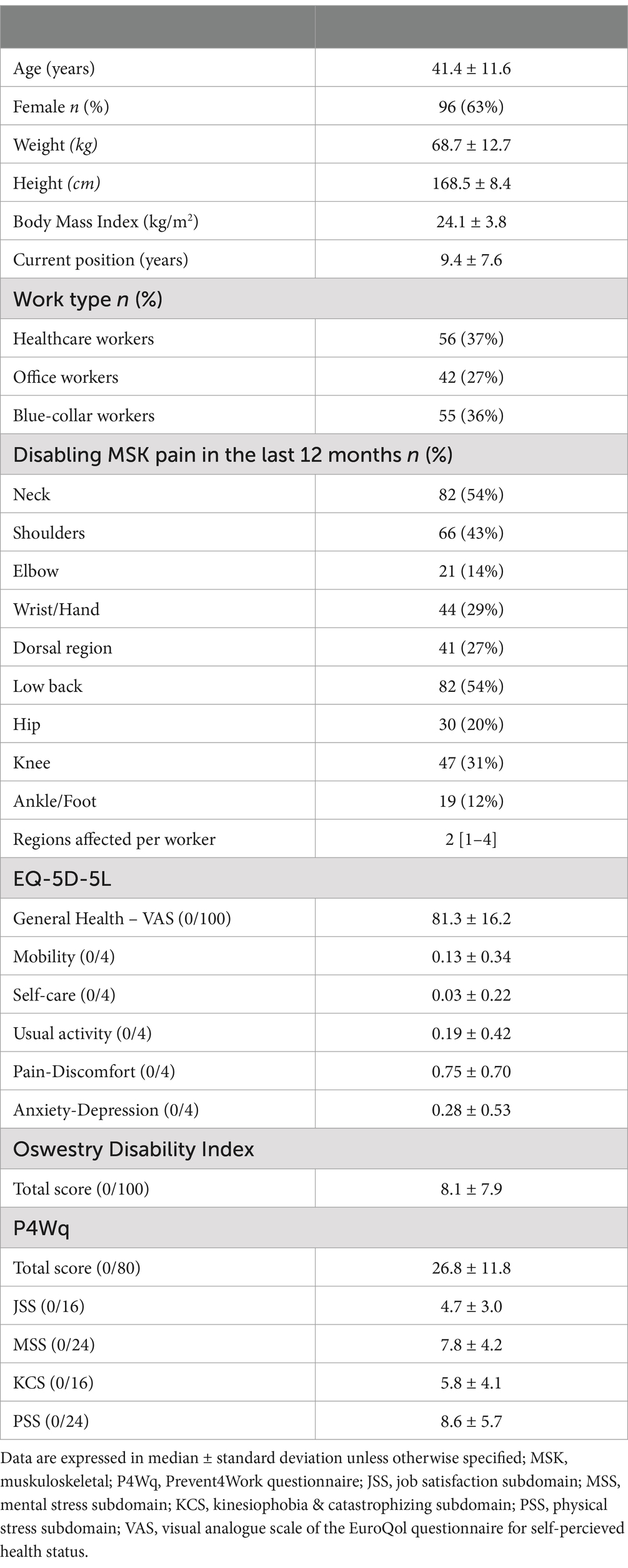

3.2 Participants characteristics for the validity studyTable 2 presents the sociodemographic and questionnaire scores of 153 out of 154 workers in Spain who completed the Spanish version of the P4W. One worker, for unknown reasons, did not complete all the items and was removed from the analysis. A total of 119 (77%) workers reported disabling musculoskeletal pain in the spinal region (i.e., neck, thoracic, or low back) in the previous 12 months, with a median pain intensity of 4 out of 10 [IQR 3–5].

Table 2. Characteristics of the participants.

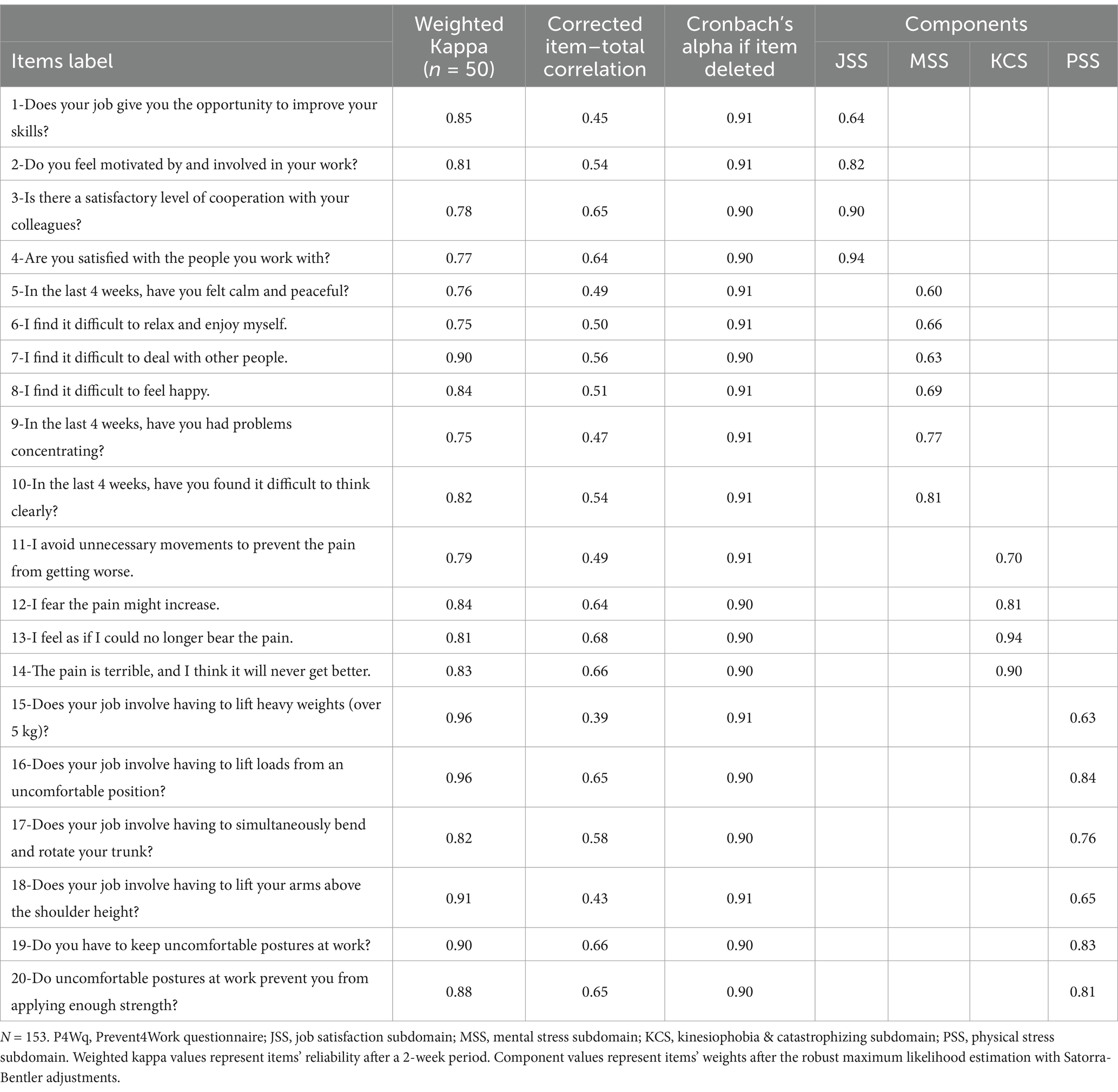

3.3 Structural validityKaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity demonstrated adequate sample composition for the questionnaire (KMO = 0.872; p < 0.001) versions. The confirmatory factor analysis showed a four-factor model with almost all factor loadings greater than 0.40, confirming the biopsychosocial dimensions of the questionnaire with the 4 pre-established domains. The factor loadings of the different items are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Confirmatory factor analysis, internal consistency indicators, and item’s reliability of the Spanish version of the P4Wq.

All the goodness-of-fit statistics indicated a ‘good fit’ for the Spanish version of the P4Wq (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, SRMR = 0.074; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEA = 0.07; Comparative Fit Index, CFI = 0.93; Tucker–Lewis Index, TLI = 0.92).

3.4 Internal consistencyThe internal consistency for the total score of the P4Wq was acceptable according to the Cronbach’s alpha values (α = 0.91). Similarly, acceptable internal consistency was found for the domains sub-scores (αJSS = 0.90; αMSS = 0.85; αKCS = 0.91; αPSS = 0.88). Corrected item-total correlations and Cronbach’s α if item deleted was calculated are presented in Table 3.

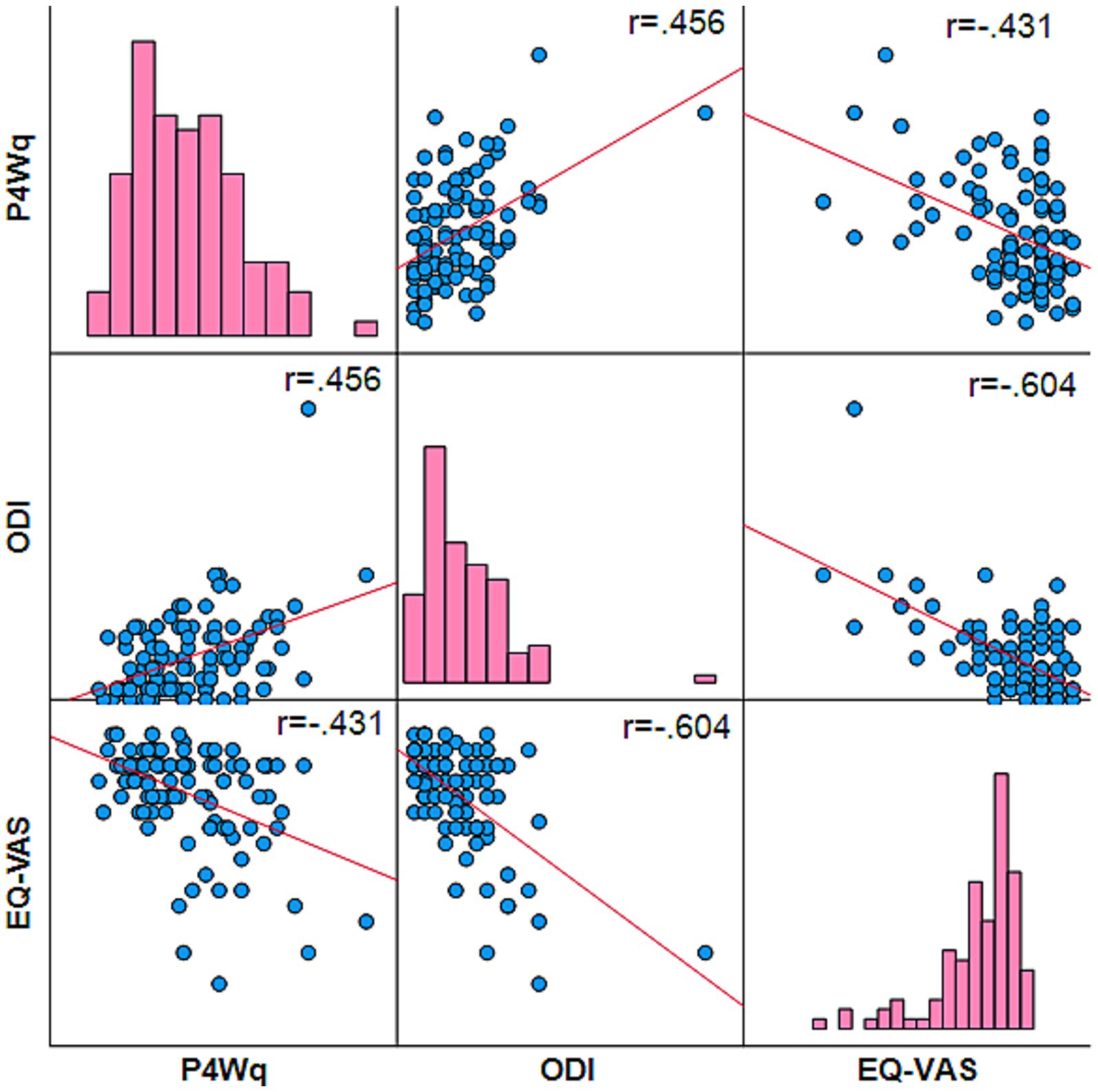

3.5 Convergent validityThe P4Wq total score showed a moderate negative association with the indicator of quality of life (i.e., EQ-VAS) (ρ = −0.43; p < 0.001) and moderate positive association with the disability index (i.e., ODI) (ρ = 0.46; p < 0.001). Figure 1 represents the score distribution and between variables association.

Figure 1. Scatter plots and histograms for the P4Wq, ODI, and EQ-VAS. P4Wq, Prevent for Work Questionnaire; ODI, the Oswestry Disability Index; EQ-VAS, visual analogue scale for the general health status of the EuroQol questionnaire. The associations were statistically significant for all variables after Pearson’s correlation test (two-tailed, p ≤ 0.001).

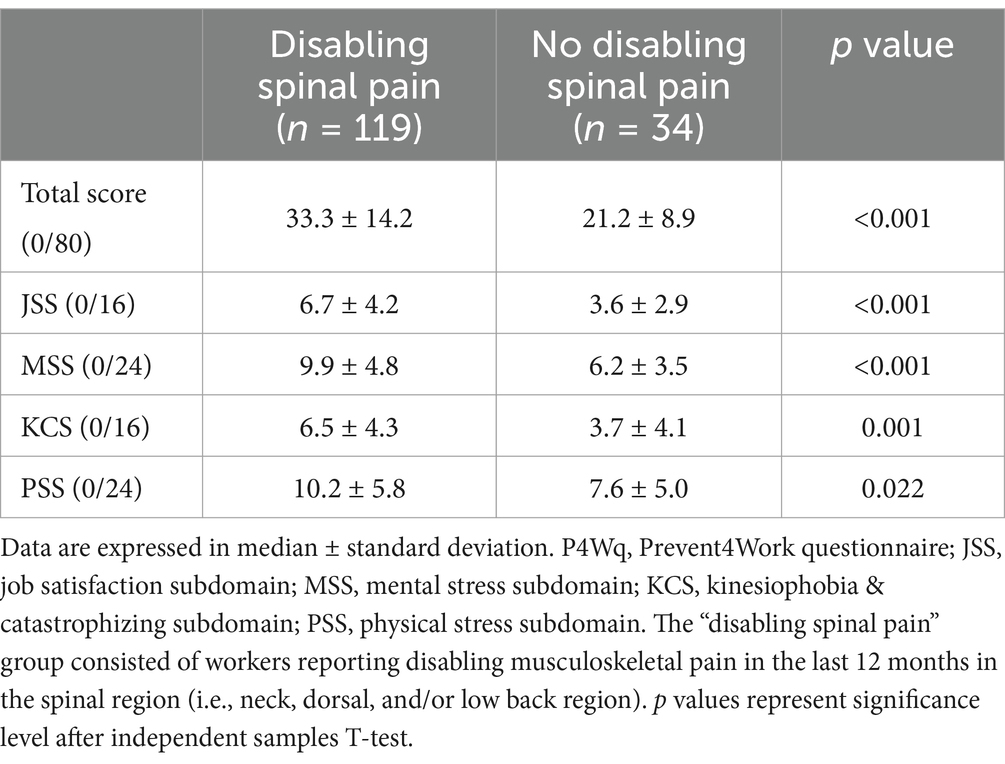

3.6 Known-groups validityFor the Spanish workers, the “disabling spinal pain” group showed higher total score (mean difference = 12.1; p < 0.001; d = 1.10) and the subscales of job satisfaction (mean differenceJSS = 3.0; p < 0.001; d = 0.80), mental stress (mean differenceMSS = 3.7; p < 0.001; d = 0.90), kinesiophobia & catastrophizing (mean differenceKCS = 2.8; p = 0.001; d = 0.70), and physical stress (mean differencePSS = 2.5; p = 0.022; d = 0.50) domains compared with the “no disabling spinal pain” group. Descriptive statistics depicted by the group are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. P4Wq scores comparisons between participants with and without history of disabling spinal pain in the last 12 months.

3.7 Floor and ceiling effectsThe analyses of the distribution of frequencies regarding the total score indicated an absence of floor or ceiling effects, presented in Figure 1. No responders achieved the highest or lowest scores in the total score.

3.8 Test–retest reliability and error of measurementTest–retest reliability and error of measurement were tested. More specifically, fifty workers (36.8 ± 10.1, 64% females) completed the test–retest after a two-week period (14 ± 2 days).

The test–retest reliability was good to excellent for all items with the weighted Kappa coefficients ranging from 0.75 to 0.96 as presented in Table 3.

The test–retest reliability was ‘good’ for the total score (ICC = 0.98) and JSS (ICC = 0.91), MSS (ICC = 0.94), KCS (ICC = 0.96), and PSS (ICC = 0.98) domains. The specific values of the ICC (3,1) with 95% confidence interval, SEM, MDC95 and MDC90 for the total scores and domains sub-scores of the P4Wq are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Test–retest reliability and measurement error indicators.

3.9 Subgroups analysisSubgroups analysis for sex, age categories, and work type are detailed in the Supplementary material. All subgroups showed comparable levels of adequate internal consistency and convergent validity.

The linear regression models showed that the work type was associated with the P4Work total score (p = 0.003), and the domains of KCS (p = 0.004) and PSS (p < 0.001). The linear regression models showed no associations with sex or age categories. Specifically, office workers showed lower total P4Work score and PSS domain than healthcare workers and blue-collar workers (p < 0.001), while blue-collar workers showed higher scores in the KCS domain than office workers (p = 0.010).

4 DiscussionThe objective of this study was to translate and culturally adapt the original Italian version of the P4Wq into European-Spanish, and subsequently assess its psychometric properties in a working population. This version demonstrated good face validity, structural validity, internal consistency, construct validity, known-groups validity, floor and ceiling effects, and test–retest reliability.

4.1 Cross-cultural adaptation and face-validity processesThe translation of the P4Wq underwent a rigorous and systematic process to ensure semantic equivalence with the original version in Italian. Spanish participants demonstrated adequate interpretation and understanding of all questionnaire items, with no items requiring special attention. Minor discrepancies encountered in the forward-and backward-translation process, primarily related to the use of verbs and synonymous words, are considered normal in translations and cultural adaptations of questionnaires (41) and were resolved by the group.

4.2 Structural validity and internal consistencyThe four-factor solution for the Spanish version closely resembled the results obtained in the original P4Wq version, in which the four subdomains (JSS, MSS, KCS, and PSS) comprehensively assess the worker from a biopsychosocial perspective (18, 19). Additionally, all goodness-of-fit statistics indicated a ‘good fit’ for the Spanish version.

Moreover, the internal consistency values, reflected by the Cronbach’s α, resembled the original version for the total score (α = 0.89) and domains sub-scores (0.82 < α < 0.91) (19).

4.3 Construct validity and floor/ceiling effectsIn line with the original version with Italian workers, the total scores of the Spanish version of P4Workq showed a moderate positive correlation with the ODI and a moderate negative correlation with the EQ-VAS. Based on the analysis in the sample of Spanish workers, the P4Wq appears to mitigate the floor effect observed in the ODI and the ceiling effect seen in the EQ-VAS (19). This result suggests a higher sensitivity of the P4Wq for classifying populations of active workers. Furthermore, the P4Wq offers promising ability to stratify differentiate between healthy workers with a history of disabling spinal pain, which could be predictive of future musculoskeletal pain events or long-term sick leave from work (42). Additionally, the differences in effect sizes between groups would be considered as moderate-large for the total score and most domain sub-scores, which were at or above the SEM. However, despite being statistically significant, the physical stress subdomain showed a lower discriminative ability between groups compared to the rest of the subdomains. These differences not only in the physical domain reinforces the biopsychosocial view of MSK pain, which extends beyond exclusively physical and ergonomic factors (18), which reinforces the P4Wq ability to capture the multifactorial nature of work-related pain.

4.4 Test–retest reliability and error of measurementFor the reliability results after 2 weeks, item response stability demonstrated good to excellent reliability for all items based on the weighted Kappa coefficients (43), comparable to the values obtained in the original version (19).

Notably, this study is the first to evaluate test–retest reliability for the P4Wq, finding a moderate to excellent reliability for both the total and domain sub-scores, and allowing the calculation of the SEM and the MDC to be considered in future studies. In this study, both the MDC90 and MDC95, ranged between 4 to 5 points for the total score and between 2 to 3 points for the domain subs-cores, suggesting that the smallest detectable change would lie between 6 to 13% of the maximum scores.

4.5 Clinical implicationsThe validation of the P4Wq into Spanish extends its utility beyond the original Italian population, offering a reliable and culturally adapted tool for Spanish workers. Given the multifaceted nature of work-related MSK pain, this questionnaire allows healthcare professionals to assess key factors contributing to MSK pain within a biopsychosocial framework. For example, the questionnaire allows for early identification of workers at risk of developing pain indifferent activity sectors (e.g., office workers, healthcare workers, blue-collar workers). Moreover, the Spanish version of the P4Wq supports cross-cultural research initiatives and the development of evidence-based occupational policies to reduce MSK pain and improve workers’ health.

4.6 LimitationsThe primary limitation of the Spanish version of the P4Wq was the exclusion of workers on sick leave from the study sample, restricting the generalizability of results to the active working population. Given the association between negative pain beliefs and early withdrawal from the labor market (44), future studies should assess the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the P4Wq in samples of workers on sick leave, and also in workers with self-reported chronic spinal pain. More importantly, a broad implementation of the questionnaire in working population would be valuable as this might help understanding whether the questionnaire can identify workers at risk of developing debilitating MSK pain. Future evaluations should thus include responsiveness and predictive capacity for new occurrences of MSK pain or long-term sick leave (42).

5 ConclusionIn conclusion, the Spanish version of the P4Wq was face-valid and exhibited a similar structure to the original version, as well as good internal consistency and construct validity. Furthermore, the Spanish version exhibited excellent test–retest reliability and, for the first time, provided values for measurement error. Additionally, it is suitable for use within the active working population and are valuable tools for a brief yet comprehensive biopsychosocial evaluation of factors related to the development of work-related MSK pain.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee at San Jorge University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributionsJB-A: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PB-L: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VD-G: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. TP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Julia Blasco-Abadía is a predoctoral research fellow supported by the Grant PIF 2022–2026 from the Gobierno de Aragón (Spain) and the Grant FPU23/1797 from the Spanish Ministry of Universities. Julia Blasco-Abadía, Pablo Bellosta-López, and Víctor Doménech-García are supported by Departamento de Ciencia, Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, from the Gobierno de Aragón (Spain) (Research Group MOTUS B60_23D). This work was supported by Ayudas a Proyectos Internos de Investigación Universidad San Jorge curso 2023–2024 grant number PI 2024 MOTUS-2324017.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the institutions that have made this study possible, especially Sociedad Aragonesa de Gestión Agroambiental, Cárnicas Cinco Villas, and Hospital San Juan de Dios; and all the people who have been part of or collaborated with the Prevent4Work project. We thank ChatGPT-4.0 for their help in revising the grammar of some sentences in this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1453492/full#supplementary-material

References1. Krishnan, KS, Raju, G, and Shawkataly, O. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: psychological and physical risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9361. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179361

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Briggs, AM, Woolf, AD, Dreinhöfer, K, Homb, N, Hoy, DG, Kopansky-Giles, D, et al. Reducing the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. (2018) 96:366–8. doi: 10.2471/blt.17.204891

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Tousignant-Laflamme, Y, Houle, C, Longtin, C, Gérard, T, Lagueux, E, Perreault, K, et al. Prognostic factors specific to work-related musculoskeletal disorders: an overview of recent systematic reviews. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. (2023) 66:102825. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2023.102825

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Bellosta-López, P, Domenech-Garcia, V, Palsson, TS, Christensen, SW, Silva, PB, Langella, F, et al. European knowledge alliance for innovative measures in prevention of work-related musculoskeletal pain disorders (prevent 4Work project): protocol for an international mixed-methods longitudinal study. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e052602. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052602

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. de Kok, J, Vroonhof, P, Snijders, J, Roullis, G, Clarke, M, Peereboom, K, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: Prevalence, costs and demographics in the EU. Luxembourg: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2019).

6. Keyaerts, S, Godderis, L, Delvaux, E, and Daenen, L. The association between work-related physical and psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal disorders in healthcare workers: moderating role of fear of movement. J Occup Health. (2022) 64:e12314. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12314

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Frasie, A, Houry, M, Plourde, C, Robert, MT, Bouyer, LJ, and Roy, JS. Feedback for the prevention and rehabilitation of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Work. (2023) 76:61–94. doi: 10.3233/wor-220545

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Isusi, I. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders – Facts and figures. Luxembourg: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2020).

10. Otero-Ketterer, E, Peñacoba-Puente, C, Ferreira Pinheiro-Araujo, C, Valera-Calero, JA, and Ortega-Santiago, R. Biopsychosocial factors for chronicity in individuals with non-specific low back pain: an umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191610145

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Edwards, RR, Dworkin, RH, Sullivan, MD, Turk, DC, and Wasan, AD. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. J Pain. (2016) 17:T70–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Rashid, M, Heiden, M, Nilsson, A, and Kristofferzon, ML. Do work ability and life satisfaction matter for return to work? Predictive ability of the work ability index and life satisfaction questionnaire among women with long-term musculoskeletal pain. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:584. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10510-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Cuenca-Zaldívar, JN, Fernández-Carnero, J, Sánchez-Romero, EA, Álvarez-Gonzalo, V, Conde-Rodríguez, R, Rodríguez-Sanz, D, et al. Effects of a therapeutic exercise protocol for patients with chronic non-specific Back pain in primary health care: a single-group retrospective cohort study. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:12. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206478

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Martínez-Pozas, O, Sánchez-Romero, EA, Beltran-Alacreu, H, Arribas-Romano, A, Cuenca-Martínez, F, Villafañe, JH, et al. Effects of orthopedic manual therapy on pain sensitization in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: an umbrella review with Meta-Meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2023) 102:879–85. doi: 10.1097/phm.0000000000002239

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. OECD. Sickness, disability and work: Breaking the barriers: A synthesis of findings across OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing (2010).

16. Fresk, M, Grooten, WJA, Brodin, N, Backlund, LG, Arrelöv, B, Skånér, Y, et al. Mapping information regarding the work-related disability of depression and long-term musculoskeletal pain to the international classification of functioning, disability and health and ICF Core sets. Front Rehabil Sci. (2023) 4:1159208. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1159208

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Artiles-Sánchez, J, Fernández-Carnero, J, Sánchez-Romero, EA, Cuenca-Zaldívar, JN, Martinez-Lozano, P, Meléndez-Oliva, E, et al. Multicomponent exercise program to avoid productivity loss due to COVID-19: A prospective study with a brief report of 2-year follow-up. Topics Geriatr. Rehab. (2024) 40:175–83. doi: 10.1097/tgr.0000000000000439

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Langella, F, Christensen, SWM, Palsson, TS, Høgh, M, Gagni, N, Bellosta-López, P, et al. Development of the prevent for work questionnaire (P4Wq) for assessment of musculoskeletal risk in the workplace: part 1-literature review and domains selection. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e043800. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043800

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Langella, F, Vanni, D, Høgh, M, Palsson, TS, Christensen, SWM, Bellosta-López, P, et al. Development of the prevent for work questionnaire (P4Wq) for the assessment of musculoskeletal risk factors in the workplace: part 2-pilot study for questionnaire development and validation. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e053988. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053988

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Mokkink, LB, Terwee, CB, Patrick, DL, Alonso, J, Stratford, PW, Knol, DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. (2010) 19:539–49. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Beaton, DE, Bombardier, C, Guillemin, F, and Ferraz, MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. (2000) 25:3186–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Blasco-Abadía, J, Bellosta-López, P, Palsson, T, Moreno González, S, García-Campayo, J, and Doménech-García, V. Spanish version of the pain beliefs questionnaire: translation, cross-cultural adaptation, validation, and psychometric properties in a working population. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. (2023) 66:102827. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2023.102827

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Papaefstathiou, E, Tsounis, A, Malliarou, M, and Sarafis, P. Translation and validation of the Copenhagen burnout inventory amongst Greek doctors. Health Psychol Res. (2019) 7:7678. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2019.7678

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Hernandez, G, Garin, O, Pardo, Y, Vilagut, G, Pont, À, Suárez, M, et al. Validity of the EQ-5D-5L and reference norms for the Spanish population. Qual Life Res. (2018) 27:2337–48. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1877-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Jensen, MB, Jensen, CE, Gudex, C, Pedersen, KM, Sørensen, SS, and Ehlers, LH. Danish population health measured by the EQ-5D-5L. Scand J Public Health. (2023) 51:241–9. doi: 10.1177/14034948211058060

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Selva-Sevilla, C, Ferrara, P, and Gerónimo-Pardo, M. Psychometric properties study of the Oswestry disability index in a Spanish population with previous lumbar disc surgery: homogeneity and validity. Spine. (2019) 44:E430–e437. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000002867

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Comins, J, Brodersen, J, Wedderkopp, N, Lassen, MR, Shakir, H, Specht, K, et al. Psychometric validation of the Danish version of the Oswestry disability index in patients with chronic low Back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2020) 45:1143–50. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003486.

留言 (0)