Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is one of the most common malignant mesenchymal tumors and is composed of cells that exhibit distinct features of the smooth muscle lineage (1). LMS most commonly occurs in the uterus. A perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) is a mesenchymal tumor that originates from histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) lines characterized by the coexpression of melanocytic and muscle markers (2). A PEComa arising from the female genital tract accounts for nearly 25% of all PEComa cases and the uterine corpus is the most commonly affected organ. The distinction between an LMS and a PEComa is quite challenging. In this study, we report the case of a 39-year-old woman and discuss the diagnosis and treatment of an LMS and a PEComa.

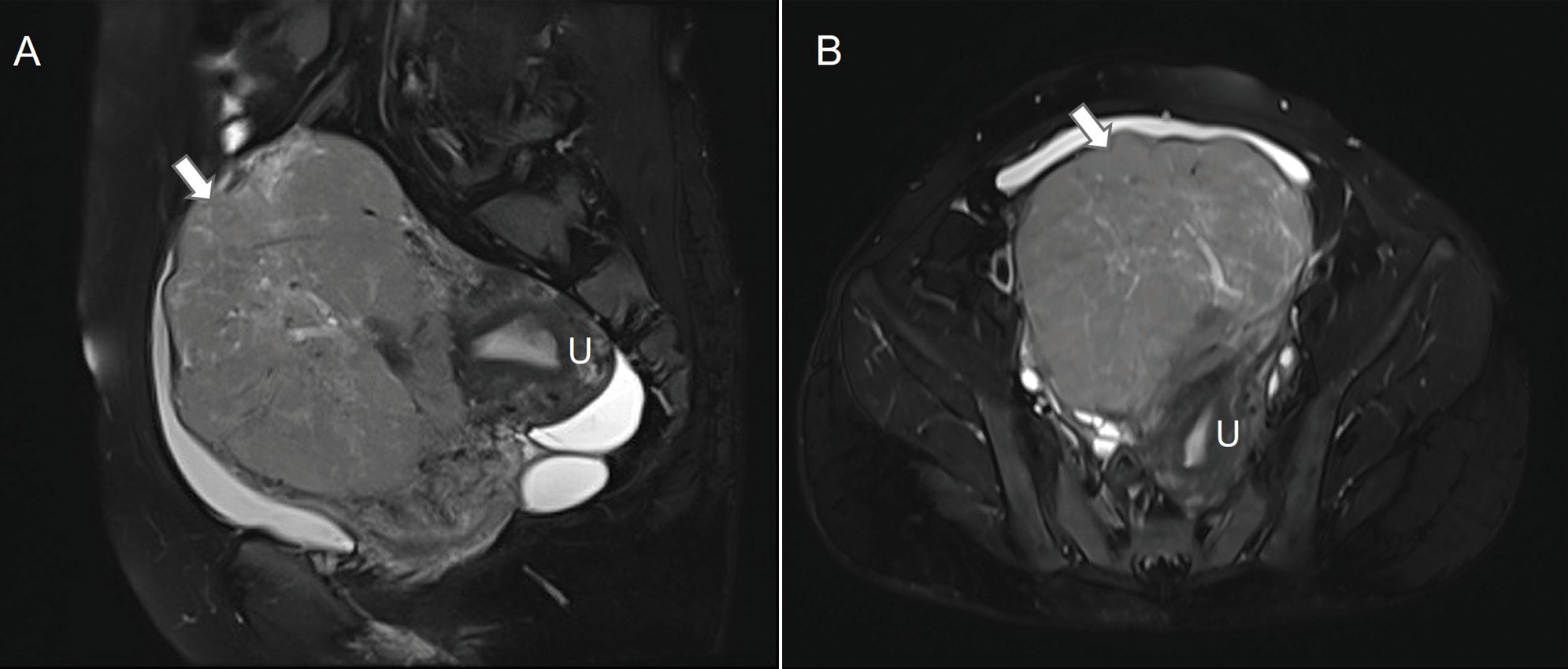

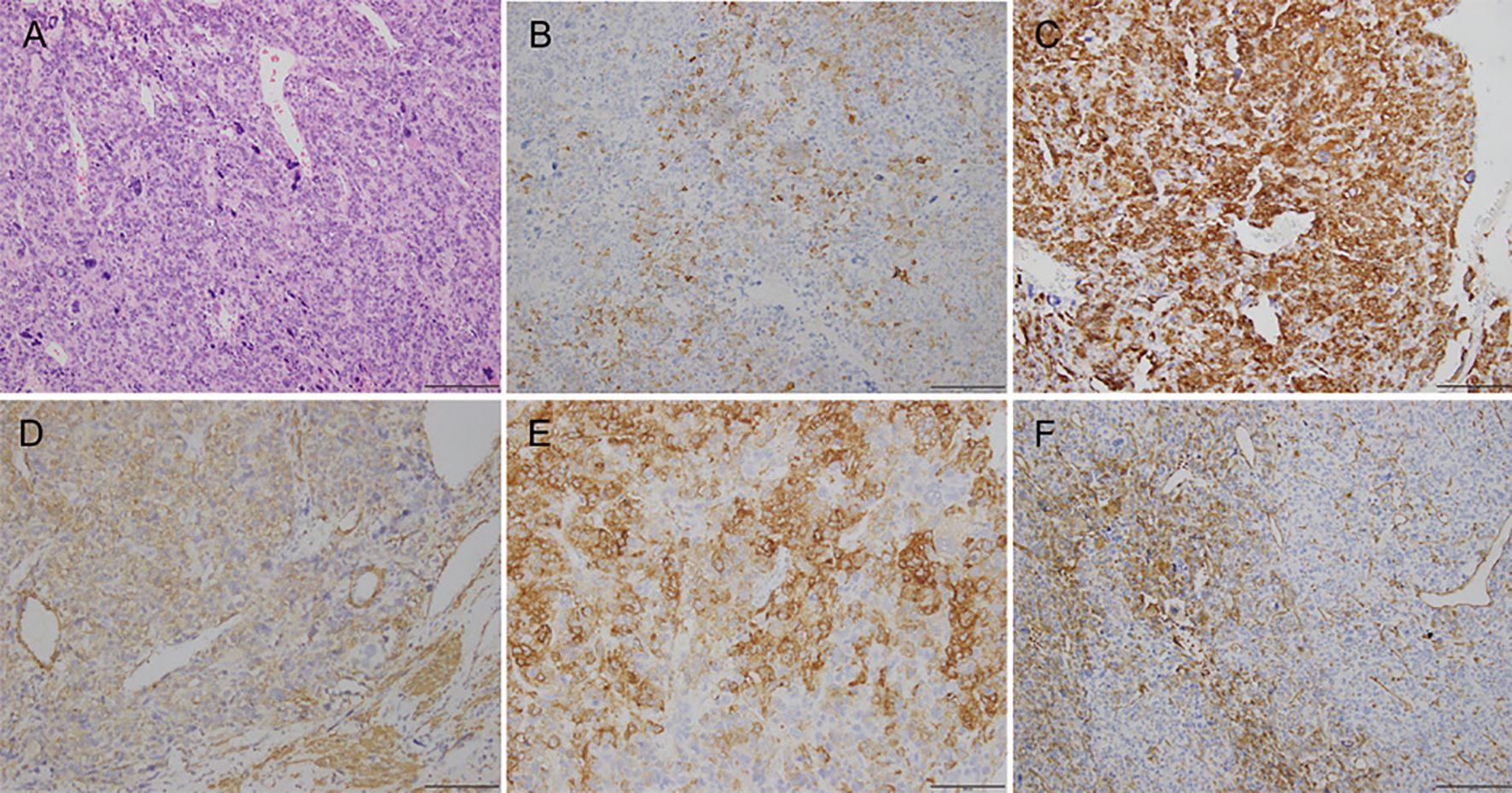

Case reportA 39-year-old woman (gravida 1, para 1) presented at our hospital with increased urinary frequency for the previous 3-4 months. The patient had no history of abnormal uterine bleeding, low abdominal pain, or weight loss. She had no significant medical, surgical, or family history. She had no history of smoking, drug use, or drinking. Serum levels of CEA, CA125, CA19-9, AFP, CA242, CA153, HE4, and NST were measured as part of a routine workup and the results were all negative. A gynecological examination revealed a uterine size as large as that observed at 18 gestational weeks. A gynecological B ultrasonic examination revealed an 11*10*9 cm low-echo mass arising from the anterior aspect of the uterus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 10*12*15 cm mass arising from the right anterior aspect of the uterus, and a subserosal uterine myoma with degeneration was diagnosed (Figure 1). On the basis of the preoperative examination results, a hysteroscopic myomectomy was performed first. A 12 cm mass was observed in the right anterior aspect of the uterus. The surface of the mass was covered with blood vessels. On gross examination, the mass was soft and fleshy. An intraoperative frozen section pathological examination revealed that the mass was likely to be a mesenchymal malignancy. After consultation with her family, a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. Immunohistochemical staining revealed the expressions of HMB45 (partly+), SMA (+), DES (++), H-caldesmon (+), Vimentin (partly+), Ki67 (60%+), MyoD1 (cytoplasm+), INI-1 (+), BRG-1 (+), BRM (+), A103 (-), NL2 (focal+), EMA (partly+), caldesmon (++), ER (partly+), PR (partly+), CD10 (focal+), P53 (+), CD117 (-), CD31 (vessel+), CD34 (vessel+) and D240 (vessel+) (Figure 2). The histopathological diagnosis was suggestive of leiomyosarcoma, but a malignant PEComa could not be completely excluded. Genetic testing was recommended but unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Figure 1. Pelvic magnetic resonance image of the mass in the uterus. On sagittal (A) and horizontal (B) T2-weighted images, the mass (arrows) abutted the uterus (U).

Figure 2. Photomicrographs showing (A) hematoxylin-eosin staining; (B) immunohistochemical staining for HMB45; (C) immunohistochemical staining for DES; (D) immunohistochemical staining for SMA; (E) immunohistochemical staining for H-caldesmon; (F) immunohistochemical staining for vimentin.

DiscussionThis case report shows interesting features that might help other gynecologists approach the diagnosis and treatment of an LMS or a PEComa.

Currently, no clinical symptoms can provide effective preoperative diagnostic modalities for an LMS or a PEcoma. Patients with an LMS present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, a palpable pelvic mass, and/or pelvic pain. Common symptoms of a PEComa include altered menstruation, irregular vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or the identification of a mass on imaging (2, 3). The diagnosis is not established until pathological and immunohistochemical analyses of the surgical specimen are carried out in a large percentage of cases. Our case only presented with a large pelvic mass with increased urinary frequency.

The preoperative diagnosis of a subserosal uterine myoma with degeneration was made by our radiologists via MRI. MRI has the greatest potential to be an effective screening tool for an LMS. Low ADC values, irregular margins, and T2 intermediate/hyperintensity are observed more often in patients with an LMS. The combination of low ADC values and the presence of an irregular margin may be a more specific characteristic, whereas the presence of a T2 intermediate/high signal may be more sensitive (4). Some reports have indicated that arteriovenous hypervascularity in contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images may be a feature of a PEComa (5). Diagnosing LMS or a PEComa solely through preoperative imaging (including CT and MRI) is a challenging task.

Histopathological assessment is the standard method for the diagnosis of an LMS and a PEComa. The cut surfaces of an LMS are typically soft, bulging, fleshy, necrotic, hemorrhagic, and lack the prominent whorled appearance of a leiomyoma. LMS is classified into three subtypes: spindle-type, myxoid-type, and epithelioid-type (6). The cut surfaces of a PEComa are soft to firm and vary in color (pink, tan-brown, yellow-brown, white, gray-white), with a subset showing friability, hemorrhage, or necrosis. PEComa is generally classified into three subgroups: spindle-type, epithelioid-type, and admixed-type (7). The differential diagnosis is still challenging in terms of histopathology since LMSs and PEComas can both present with epithelioid, spindle-shaped or mixed pattern epithelioid and spindle-shaped cells. A delicate vascular network may be characteristic of a PEComa (8).

Because some of morphological features are not unique to an LMS compared with a PEComa, specific immunohistochemical stains are required to support the morphological diagnosis. The majority of LMSs are immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), desmin, and h-caldesmon. Approximately one-third of leiomyosarcomas focally express HMB-45 (9). PEComas are immunoreactive for both smooth muscle (desmin, SMA, muscle-specific-actin, muscle myosin, and calponin) and melanocytic (HMB-45, Melan-A/MART-1, tyrosinase, and MITF) markers (10). The two main morphological subtypes of a gynecological PEComa have been described. One subtype, which is closely reminiscent of a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, exhibits strong HMB-45 expression with only focal smooth-muscle marker positivity. The other type, which exhibits overlapping morphological and immunohistochemical features with epithelioid smooth muscle tumors, exhibits lower HMB-45 expression and more extensive smooth-muscle marker positivity. It has been proposed that two or more melanocytic markers (preferably HMB-45 and Melan A) or one melanocytic marker and cathepsin K are enough to indicate a diagnosis of PEComa (11). In the light of the immunohistochemical results of our patient—HMB45 (partly+), SMA (+), DES (++), and H-caldesmon (+)—the diagnosis remains uncertain.

Given the immunophenotypic overlap that exists between PEComas and LMSs, genomic characterization is needed for differential diagnosis. An LMS is a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm originating from smooth muscle cells. Exome sequencing has shown that TP53, RB1, ATRX, PTEN, and MED12 are frequently mutated in LMSs (12). A PEComa is a mesenchymal tumor thought to originate from PEC lines. Immunophenotypic and molecular overlap advocate for the hypothesis that modified smooth muscle cells represent the origin of a subset of PEComas (13). Recurrent alterations were also identified in TP53, RB1, ATRX, and BRCA2 in PEComas (14). TSC alterations/TFE3 fusions are characteristic of uterine PEComas (9). TFE3-rearranged PEComas were identified as a distinctive subset of PEComas. SFPQ was the most common TFE3 fusion partner, followed by the ASPSCR1 and NONO genes (15). A significant subset of PEComas show overexpression of MITF in the absence of TFE3 expression (16). Additionally, the novel RAD51B gene fusion is observed exclusively in uterine PEComas (17). Unfortunately, our case was not explored by further molecular analysis to help in the differential diagnosis.

For an LMS or a PEComa, the effective treatment is surgical removal with negative surgical margins including a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (10, 18). Although the risk of recurrence after complete resection of an LMS is high, adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy administered after complete resection does not significantly improve the oncological outcome. For a PEComa, only anecdotal and inconclusive data are available for the use of adjuvant radiotherapy.

ConclusionIn summary, we present an unusual case that cautions that large pelvic masses may present atypically. Uterine PEComa cases are rare. One type of uterine PEComa has morphological and immunohistochemical features that overlap those of an LMS and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. We hope that this case may contribute to increasing the awareness of PEComas and ultimately to avoiding clinical misdiagnosis, missed diagnosis, and treatment delay.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committees of the International Peace Maternity and Child Health Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from a patient undergoing surgery in our hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsZC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QL: Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81702546).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbbreviationsPEComa, perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; SMA, smooth muscle actin; DES, desmin; MITF, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; TFE3, Transcription Factor E3; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

References1. Kostov S, Kornovski Y, Ivanova V, Dzhenkov D, Metodiev D, Watrowski Rafał, et al. New aspects of sarcomas of uterine corpus—A brief narrative review. Clin Pract. (2021) 11:878–900. doi: 10.3390/clinpract11040103

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Gu J, Wang W, Wang S. A retrospective case study of 13 uterine perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) patients. Onco Targets Ther. (2021) 14:1783–90. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S300523

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Tan Y, Zhang H, Xiao EH. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumour: Dynamic CT, MRI and clinicopathological characteristics—Analysis of 32 cases and review of the literature. Clin Radiol. (2013) 68:555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.10.021

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Shi Y, Zhong J, Zhao M, Wu J, Hai L, Xu X, et al. Histopathologic characteristics and immunotypes of perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa). Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2019) 12:4380–9.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

10. Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa) of the female genital tract: A challenging question for gynaecologic oncologist and pathologist. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2020) 33:100603. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2020.100603

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Bennett JA, Ordulu Z, Pinto A, Wanjari P, Antonescu CR, Ritterhouse LL, et al. Uterine PEComas: correlation between melanocytic marker expression and TSC alterations/TFE3 fusions. Mod Pathol. (2022) 35:515–23. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00855-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Dall GV, Hamilton A, Ratnayake G, Scott C, Barker H. Interrogating the genomic landscape of uterine leiomyosarcoma: A potential for patient benefit. Cancers (basel). (2022) 14:1561. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061561

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Katsakhyan L, Shahi M, Eugene HC, Nonogaki H, Gross JM, Nucci MR, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma associated with perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: A phenomenon of differentiation/dedifferentiation and evidence suggesting cell-of-origin. Am J Surg Pathol. (2024) 48:761–72. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002208

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Anderson WJ, Dong F, Fletcher CDM, Hirsch MS, Nucci MR. A clinicopathologic and molecular characterization of uterine sarcomas classified as Malignant PEComa. Am J Surg Pathol. (2023) 47:535–46. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002028

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Argani P, Gross JM, Baraban E, Rooper LM, Chen S, Lin MT, et al. TFE3 - rearranged PEComa/PEComa-like neoplasms: report of 25 new cases expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum and highlighting its association with prior exposure to chemotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol. (2024) 48:777–89. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002218

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Hanna J, Russell-Goldman E, Baranov E, Pissaloux D, Li YY, Tirode F, et al. PEComa with MITF overexpression: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of a series of 36 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. (2024) 48:1381–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002276

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Agaram NP, Sung YS, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen HW, Singer S, et al. Dichotomy of genetic abnormalities in PEComas with therapeutic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. (2015) 39:813–25. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000389

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Asano H, Isoe T, Ito YM, Nishimoto N, Watanabe Y, Yokoshiki S, et al. Status of the current treatment options and potential future targets in uterine leiomyosarcoma: A review. Cancers (basel). (2022) 14:1180. doi: 10.3390/cancers14051180

留言 (0)