People living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH), particularly those classified as immunological non-responders (INRs), often struggle to attain normalization of CD4+ T cell counts and function despite maintaining viral suppression (1, 2). The reported prevalence of INRs varies between 9% and 45% across different countries or regions (3–11). INRs are frequently accompanied by sustained immune activation and chronic inflammation (12–15). This significant immunological impairment not only contributes to HIV disease progression but also increases the risk of mortality and the development of non-AIDS-related health issues, such as adverse neurological events (16–18). Previous studies have demonstrated that low CD4+ T cell counts are linked to HIV-associated neurological impairment and opportunistic infections in the central nervous system (CNS) (18, 19). Consequently, INRs may be more susceptible to brain impairment.

Several studies have tried to elucidate the structural and functional brain abnormalities in PLWH. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been widely employed for exploring HIV-related neurological impairment (20). Prior research has demonstrated decreased gray matter volume (GMV) in various brain regions, including the frontal and parietal cortices, insula, cingulum, basal ganglia, thalamus, and hippocampus, in PLWH receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) compared to uninfected individuals (21–24). HIV-associated neurological disorders are frequently associated with changes in subcortical and cortical area (25). Furthermore, INRs with poorer immune status may experience more severe neuropathy. A cross-sectional study has revealed a correlation between lower CD4+ T cell counts and smaller brain region volumes (26). Considering the present study’s findings, a decrease in CD4+ T cell counts may correlate with heightened severity of neurological impairment. Nevertheless, the research on the structural and functional brain characteristics of INRs remains limited.

The Inadequate immune reconstitution observed in PLWH can be attributed to various factors, including chronic inflammation, persistent immune activation and HIV reservoirs (27, 28). Chronic neuroinflammation associated with HIV infection has been linked to cognitive dysfunction and a range of structural and functional abnormalities in the brain of PLWH (29, 30). The CNS serves as a challenging HIV reservoir to eliminate (31), contributing to persistent viral presence that undermines immune reconstitution efforts in PLWH and exacerbates HIV-associated neurological impairment (32). This is crucial because the difficulty in eradicating HIV from the CNS directly impacts the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapies and the overall health outcomes for PLWH. However, there is a notable lack of studies focusing on the nervous system of INRs. The blood-brain barrier prevents direct entry of the virus into the brain, but its impact on the nervous system is partly mediated through the release of inflammatory factors and modulation of endocrine and neurotrophic factors (29, 33, 34). Thus, the hypothesis posited in this study is that HIV infection in INRs may impact the secretion of peripheral cytokines and chemokines due to persistent inflammation and immune activation. Additionally, this infection may also influence the concentrations of neurotrophic factors and endocrine factors related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to alterations in the structure and function of the brain.

Build upon this hypothesis, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of brain structure and function, alongside peripheral immunity and endocrinology, in INRs. The primary aim of this study is to elucidate the correlation between neurological abnormalities and peripheral blood immunological markers in INRs, with the ultimate objective of enhancing our understanding of neurological impairment and informing future clinical strategies.

2 Materials and methodsThis study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Youan Hospital, Capital Medical University. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and written informed consent was obtained. The research involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association revised in 2013.

2.1 ParticipantsPatients presenting with opportunistic infection, neuropsychiatric disorder, autoimmune diseases, epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, substance use disorders, or other severe diseases were excluded from the study. Only patients treated with ART and had undetectable serum viral loads were included. The clinical characteristics of the participants, including demographics, CD4+ T cell counts, HIV RNA load, date of HIV infection, duration of HIV infection, date of ART initiation, and duration of ART treatment, were obtained from the medical records of the AIDS research cohort at Beijing Youan Hospital. Participants with a total CD4+ T cell count < 500 cells/µl and/or a CD4+ T cell count increase < 30% from baseline at 2 years after ART initiation, while maintaining an undetectable plasma HIV RNA load, were classified into INRs. On the other hand, individuals with a total CD4+ T cell count > 500 cells/µl and/or a CD4+ T cell count increase > 30% from baseline at 2 years after ART initiation, with an undetectable plasma HIV RNA load, were classified into IRs. For each participant, plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were collected and stored at −80°C and in liquid nitrogen tanks, respectively. All participants provided written informed consent, as approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Youan Hospital (2023/057).

2.2 Clinical assessmentsMood and sleep assessment: The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) and Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were employed to assess the levels of anxiety and depression among all participants. Mental health status was assessed using the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was employed to assess sleep quality.

Other assessments: Childhood maltreatment history was evaluated using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). The assessment of alcohol craving included the administration of the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ).

2.3 Neuroimaging2.3.1 Image acquisitionResting-state functional MRI data were acquired using a 1.5 T Philips MRI Scanner at the Beijing Second Hospital. Participants were instructed to lie supine, maintain immobility, close their eyes, and remain awake. To minimize head movement, soft earplugs were employed. The resting-state functional images were obtained using the echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence, with the following parameters: repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 4000/25 ms, 40 slices, 64 × 64 matrix, 90°flip angle, 2.8 mm slice thickness, no gap, and 102 volumes. For 3D-T1WI: TR/TE = 2500/2.98 ms, flip angle = 7°, matrix = 64 × 64, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm × 256 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, slices = 192, scanning time 6 min 3 s.

2.3.2 Data preprocessingData preprocessing was conducted in Matlab R2013b by using SPM12. The first 10 images were discarded. Motion correction was performed on the functional images using the realign function. During this step, 9 participants were excluded from the analysis as their maximum displacements exceeded 2 mm in any of the x, y, or z axis or angular rotations exceeded 2 degrees after head motion correction. The standard DARTEL template in MNI space was used to drive DARTEL normalization. Then, regression of nuisance covariates was performed. After that, the functional MRI (fMRI) data were subjected to temporal band-pass filtering (0.01 – 0.08 Hz) and linear detrending. Additionally, spurious covariates were removed, such as the 6-head motion parameters obtained during the rigid body correction.

2.3.3 Gray matter volume data processingThe calculation of GMV was performed using SPM12. The following steps were undertaken: (1) Individual structural images were segmented into three types of brain structures: grey matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid; (2) Anatomical images were standardized to the Montreal Neurological Institute Brain Template by using the DARTEL toolkit; (3) Non-linear modulation was adopted to modulate the voxel values from density to volume; (4) Gaussian kernel Smoothing was conducted; (5) Brain GMV was quantitatively measured.

2.3.4 Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations and fractional ALFF analysisALFF was calculated by the Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit (RESTplus) version 1.2. The ALFF value was calculated for each voxel, and then normalized by dividing it by the global mean value. To obtain the standardized fALFF value for each voxel, the normalized ALFF value is divided by the ALFF value over the entire frequency band.

2.3.5 Regional Homogeneity analysisReHo analysis was conducted using RESTplus version 1.2. The Kendall coefficient of consistency (KCC) was calculated between the time series of a given voxel and the time series of its last 26 voxels. The ReHo maps were standardized by dividing the KCC value of each voxel by the mean KCC value of the whole brain. The resulting imaging data were then spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel with a full width at half maximum of 4 mm.

2.3.6 Functional connectivity analysisThe brain regions exhibiting significant differences in ALFF/fALFF, ReHo, and GMV were selected as seeds for FC analysis. Following band-pass filtering (0.01 - 0.08 Hz) and linear trend elimination, a reference time series for each seed was obtained by averaging the resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) time series of voxels within each seed. Voxel-wise Pearson’s correlation coefficients were then computed between the time series within each region of interest (ROI) and the filtered time series in the remaining brain regions. To enhance normality, a Fisher’s r-to-z transformation was applied to convert the correlation coefficients in each voxel into z-scores.

2.4 Mass cytometry and data analysisHeavy metal isotope-tagged monoclonal antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Twenty-three custom-designed antibodies were utilized to differentiate a diverse range of immune cells. These antibodies were acquired pre-conjugated from Fluidigm (South San Francisco, United States). The cell labelling procedure adhered to previously established protocols (35). The isolated PBMCs were washed and treated with Cisplatin-195Pt (Fluidigm, 201064) to eliminate diseased cells. Human TruStain FcX was employed for Fc-receptor blocking prior to antibody staining. All antibodies were utilized by the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, cell samples were then washed and stained with cell surface antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. Following this, the antibody-labelled samples were washed and incubated in 125nM Cell-ID Intercalator-Ir (Fluidigm, United States) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, United States) and stored at 4°C. The samples were resuspended at a concentration of 5.5 × 105 cells/mL in double-distilled water with a final concentration of 10% EQ Beads (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, United States). The samples were subsequently analyzed using the CyTOF2 mass cytometry system (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, United States).

The raw data of each sample were de-barcoded using unique mass tagged barcodes in a doublet-filtering scheme. A bead normalization method was employed to normalize the data files obtained from various batches. The data underwent meticulous gating using FlowJo 10.8.1 software to eliminate debris and dead cells. Subsequently, CD45+CD3+ cells and CD45+ CD3- CD14+ monocytes were manually gated for further R language analysis. The cells were divided into different clusters using PhenoGragh clustering algorithm based on their surface marker expression levels. The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), a visual dimensionality reduction algorithm, was applied for dimensionality reduction and visualization of the high-dimensional data. The distribution analysis of each cluster and marker expression, and differential analysis among different groups or sample types were performed in R software (version 3.6.0).

2.5 Cytokine and chemokine assayA comprehensive cytokine/chemokine assay was performed on plasma samples from different groups using the EMD Millipore’s MILLIPLEX® MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor Panel A MAGNETIC BEAD PANEL 96-Well Plate Assay, which utilizes the advanced Luminex® xMAP® technology. Capture antibody-coupled magnetic beads were utilized to selectively bind the target analytes in the plasma. The plate was then wrapped with foil and incubated with gentle agitation on a plate shaker overnight at a controlled temperature of 2–8°C. Following the incubation period, the plate was washed three times. Subsequently, the plate was incubated with detection reagents with gentle agitation on a plate shaker for 1 hour at room temperature (24 °C). Finally, the advanced Luminex® 200™, HTS, FLEXMAP 3D® software was employed to run the plate and analyze the resulting data.

2.6 Statistical analysesThe differences in ALFF/fALFF, ReHo, FC, gray matter volume between IRs and INRs were performed with a two-sample t-test using SPM12. The topological false discovery rate (FDR) was used for multiple comparisons correction with a significance threshold of 0.05. Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses were performed in the recovered two groups to evaluate the relationship between brain structural and functional changes (altered ALFF/fALFF, ReHo, FC and grey matter volume) and clinical variables (immunity indicators, laboratory data).

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 27.0) and R (version 3.6.0). A chi-squared test (χ2 test) or Fisher’s exact test was employed to compare INRs and IRs for categorical variables. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test to compare medians, while normally distributed data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test to compare means. Spearman correlations were used to investigate the correlation between brain alteration and immune function. The results were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1) for Windows and R (version 3.6.0). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

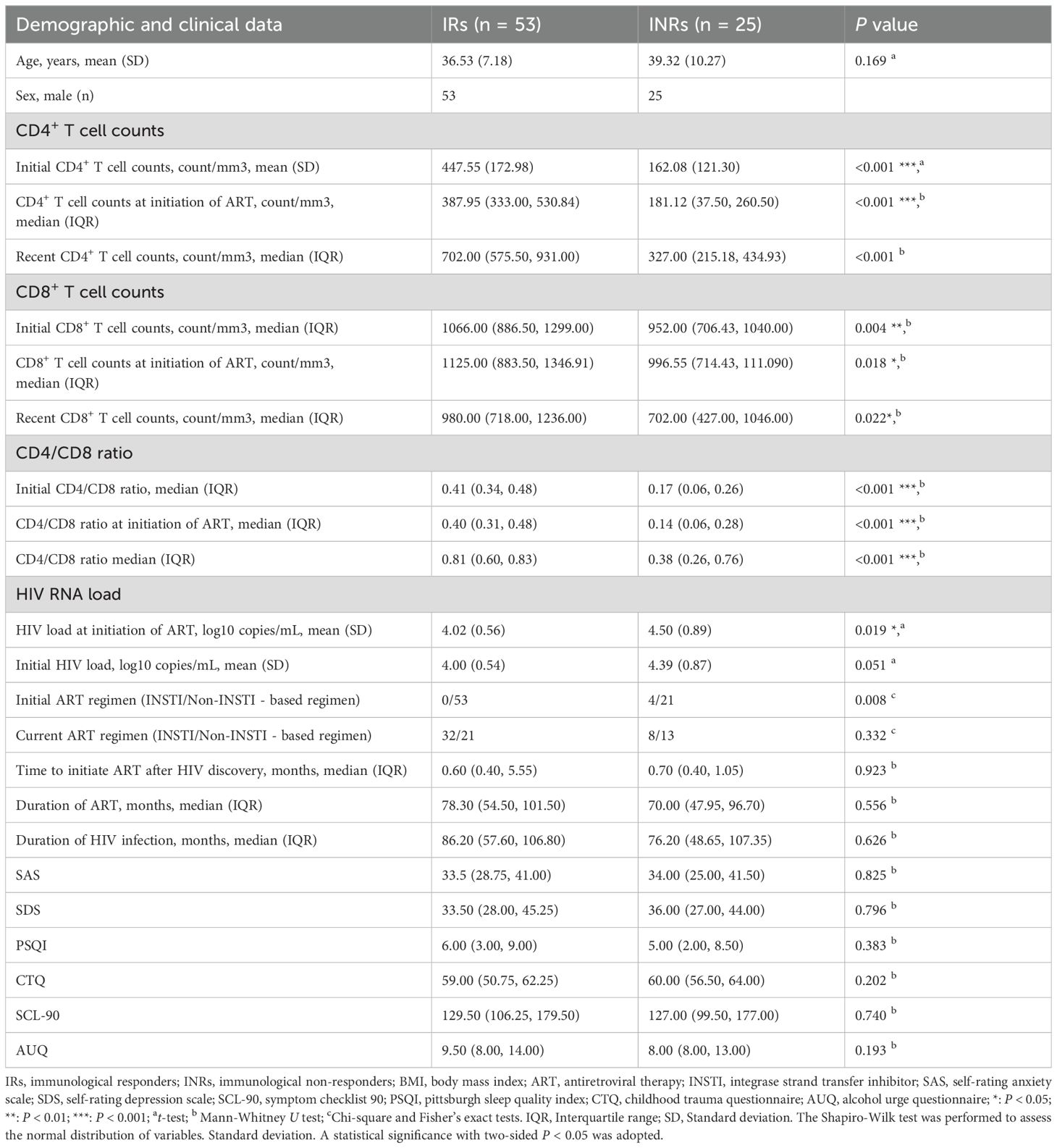

3 Results3.1 Characteristic of the participantsA total of 78 individuals with HIV infection were enrolled at Beijing Youan Hospital, Capital Medical University, from April 1, 2022, to September 31, 2022. The participants were divided into INRs (n = 25) and IRs (n = 53). Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The age, time of starting initial ART, duration of HIV infection, and duration of ART were matched between INRs and IRs. Initial CD4+ T cell counts, initial CD8+ T cell counts, recent CD4+ T cell counts, and recent CD8+ T cell counts and CD4/CD8 ratio were significantly lower in INRs, while initial HIV load was higher in INRs. These data provide critical insights into the neurological and immunological profiles of INRs and IRs. Additionally, we conducted clinical neuro-psychological assessments such as SAS, SDS, and CTQ scales (Table 1). No significant differences were observed between the INR and IR groups in these assessments.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of all subject.

3.2 Neuroimaging differences3.2.1 Gray matter volumeCompared to the IRs group, the INRs group has significantly decreased gray matter in the left lingual gyrus, right rolandic operculum (ROL), left MTG, and left postcentral gyrus (Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1. Immunological non-responders exhibit abnormal function and atrophied grey matter in their brain. (A) Gray matter atrophied in INRs. (B) Increased ALFF in INRs; (C) fALFF alteration in INRs; (D) ReHo alteration in HIV ANXs; Lingual_L: Left Lingual Gyrus; Rolandic_Oper_R: Right Rolandic Operculum; Occipital_Mid_L: Left Middle Occipital Gyrus; Temporal_Sup_L: Left Superior Temporal Gyrus; Postcentral_L: Left Postcentral Gyrus; Temporal_Mid_L: Left Middle Temporal Gyrus; Frontal_Inf_Tri_R: Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; Frontal_Sup_Medial_R: Right Superior Medial Frontal Gyrus; Frontal_Inf_Tri_L: Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; Thalamus_L: Left Thalamus. Red regions show hyperactivity, and blue regions show hypoactivity. A two-tailed two-sample t-test calculated the difference.

3.2.2 Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations and Regional HomogeneityIn this study, alterations in ALFF were observed in patients with poor immune reconstitution compared to those with immune reconstitution. To explore these differences, a two-sample t-test was performed. The results showed increased ALFF in brain regions including the left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), bilateral inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (IFGtriang), right superior frontal gyrus, and medial (SFGmed) (Figure 1B). Additionally, the analysis demonstrated significantly increased fractional ALFF (fALFF) in the left IFGtriang and the left thalamus in INRs compared to IRs (Figure 1C). Our results indicated a significantly increased ReHo in the left MTG of the INRs group when compared to the IRs group (Figure 1D).

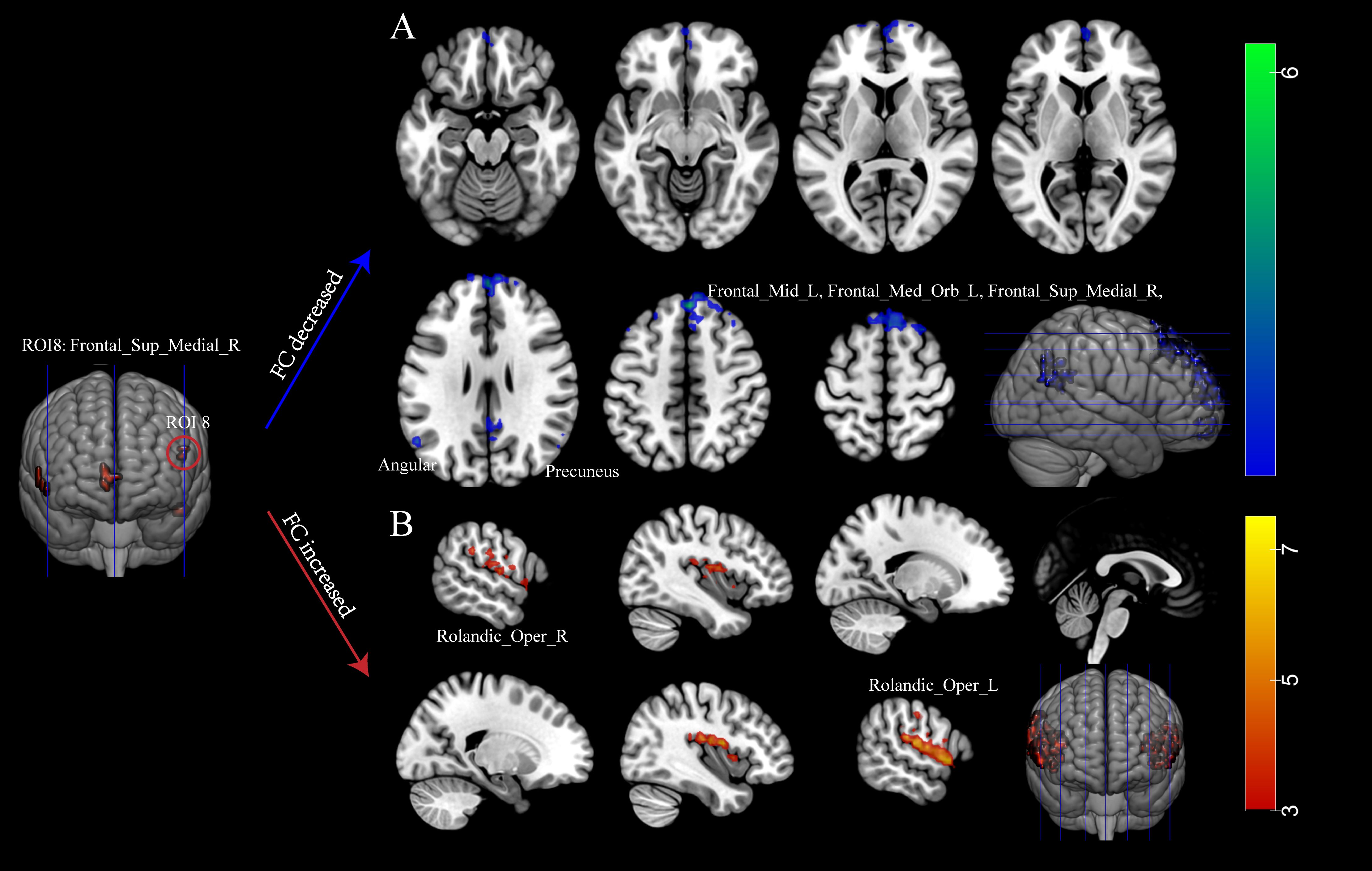

3.2.3 Functional connectivityIn this study, nine clusters were defined as the seeds to investigate the impact of abnormal intrinsic activity on FC (Figures 2A, B; Supplementary Table S4). The defined brain regions were shown in Supplementary Table S3. We found notable differences in FC were observed between the right SFGmed (ROI8) and other brain regions when comparing the INRs group and the IRs group. Significant reductions in FC were detected between ROI8 and (1) left SFGmed, (2) right SFGmed, (3) left precuneus, (4) right angular, (5) left angular, (6) right precuneus, (7) left middle frontal gyrus (MFG). Conversely, a significant increase was detected between ROI8 and bilateral ROL.

Figure 2. Immunological non-responders exhibit abnormal function connectivity. (A) Decreased FC in INRs; (B) Elevated FC in INRs. Red regions show hyperactivity, and blue regions show hypoactivity in FC. FC: functional connectivity; Frontal_Med_Orb_L: Left Medial Orbital Frontal Gyrus; Frontal_Sup_Medial_R: Right Superior Medial Frontal Gyrus; Precuneus_L: Left Precuneus; Angular_R: Right Angular Gyrus; Angular_L: Left Angular Gyrus; Precuneus_R: Right Precuneus; Frontal_Mid_L: Left Middle Frontal Gyrus; Rolandic_Oper_R: Right Rolandic Operculum; Rolandic_Oper_L: Left Rolandic Operculum. A two-tailed two-sample t-test calculated the difference.

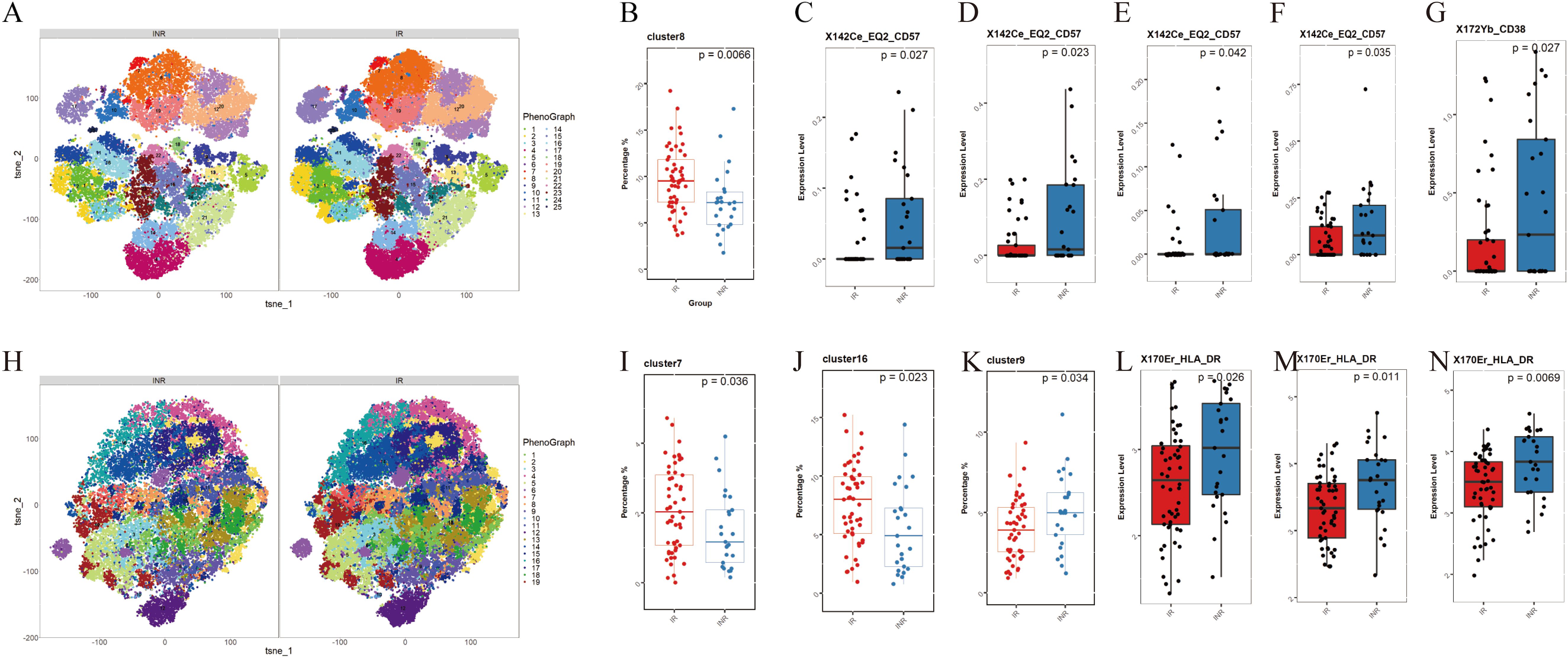

3.3 Differences in peripheral immunity between INRs and IRsWe conducted mass cytometry to PBMC samples from all participants. CD45+ CD3+ T cells and CD45+ CD3- CD14+ monocytes were analyzed (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Differences in monocyte and T cell subsets between INRs and IRs. (A) t-SNE plots of CD3+ T cells in INRs and IRs, categorized into 25 clusters based on marker expression; (B) Decreased frequency of the C8 subpopulation (CD8+ central memory T cells, TCM) in INRs; (C) Elevated CD57 expression in CD4+ naive T cells (C20) in INRs; (D, E) Elevated CD57 expression in CD4+ TCM subsets (C10, C19) in INRs; (F) Elevated CD57 expression in CD8+ TCM subsets (C15) in INRs; (G) Elevated CD38 expression in C6 in INRs; (H) t-SNE plots of CD3- CD14+ monocytes in INRs and IRs, categorized into 19 clusters based on marker expression; (I-K) Decreased frequencies of classical monocytes (C7, C16) and intermediate monocytes (C9) in INRs; (L-N) Elevated HLA-DR expression in monocyte clusters (C7, C9, C16) in INRs, indicating heightened monocyte activation. INRs: immunological non-responders; IRs: immunological responders; t-SNE: t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding. Differences in T cell and monocyte subpopulations were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test for medians and a two-tailed Student’s t-test for means, depending on the data distribution.

3.3.1 CD3+ T cellsCD3+ T cells subpopulations were categorized into 25 clusters based on the expression of markers (Figure 3A). Supplementary Table S2 provides a description of the 25 clusters representing T cells subpopulations. Among these clusters, C8 (CD8+ central memory T cells, TCM) showed significantly lower frequencies in INRs (Figure 3B). When comparing the marker expression in each cluster, we observed elevated levels of CD57 expression in T cell subpopulations including CD4+ native T cells (TN, C20) (Figure 3C), CD4+ TCM (C10, C19) (Figures 3D, E), and CD8+ TCM (C15) (Figure 3F) in the INRs. Higher CD38 expression was observed in C6 (Figure 3G). These results indicate the presence of increased activation and senescence in specific T cell subpopulations in INRs.

3.3.2 CD3- CD14+ monocytesMonocyte subpopulations were categorized into 19 clusters based on the expression of markers (Figure 3H). Supplementary Table S2 provides a description of the 19 clusters representing monocytes subpopulation. We categorized monocytes into three subtypes: classical monocytes (CM), intermediate monocytes (IM), and nonclassical monocytes (nCM). Our findings indicate that the frequencies of CM (C7, C16) and IM (C9) were significant decreased in INRs (Figures 3I–K). When comparing the marker expression in each cluster, consistently elevated levels of HLA-DR were observed across clusters (C7, C9, C16) (Figures 3L–N). This result suggests that INRs have significantly higher levels of monocyte activation.

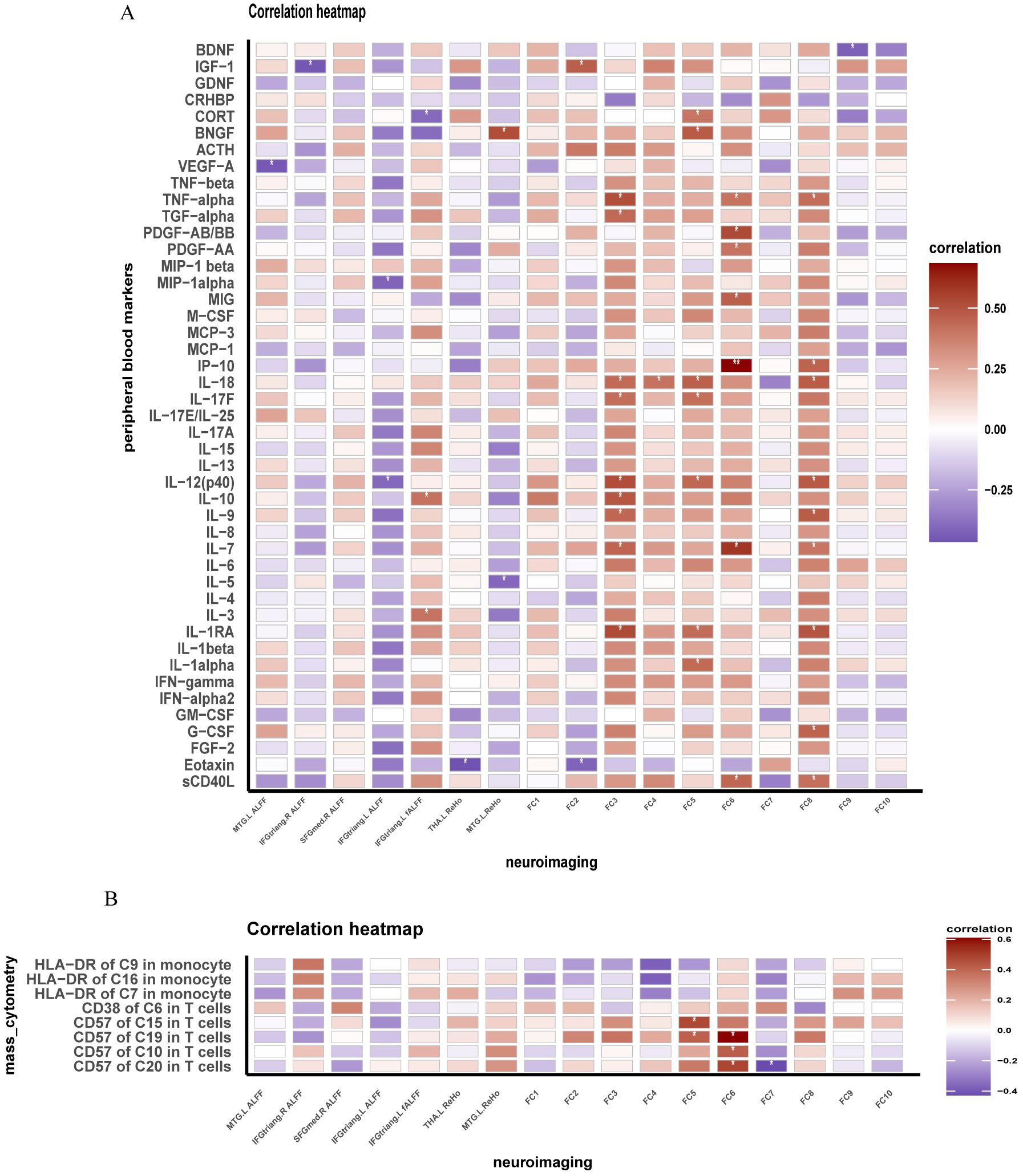

3.4 Associations between brain alterations and immunological indicators in INRsWe conducted a correlation analysis in the INRs group (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S5). Our findings revealed several significant associations. In the left MTG, ALFF showed a negative correlation with VEFG. In the left IFGtriang, ALFF showed negative correlations with IL-12 (p40) and MIP-1alpha. In the left IFGtriang, fALFF demonstrated positive correlations with IL-3 and IL-10. In the left thalamus, fALFF was negatively correlated with eotaxin. FC between ROI8 and the right SFGmed exhibited a negative correlation with eotaxin. FC between ROI8 and the left precuneus showed correlations with several cytokines including IL-1RA, IL-7, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-17F, IL-18, TGF-alpha, and TNF-alpha. FC between ROI8 and the right precuneus displayed correlations with sCD40L, IL-7, IP-10, MIG, PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB/BB, and TNF-alpha. FC between ROI8 and the right angular was correlated with IL-18. FC between ROI8 and the left angular were correlated with IL-1apha, IL-1RA, IL-12 (p40), IL-17F, and IL-18. FC between ROI8 and the left MFG were correlated with sCD40L, G-CSF, IL-1RA, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12 (p40), IL-18, IP-10, and TNF-alpha (Figure 4A). Additionally, FC between ROI8 and the right precuneus exhibited a positive correlation with the expression of CD57 in CD4+ TN and CD4+ TCM (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Brain functional changes in INRs correlate with peripheral inflammation and immunity. (A) Correlation of brain function and immune markers in INRs; (B) Correlation of brain function and markers expression levels of immune cells. INRs: immunological non-responders. FC1–FC9: The FC measures represent the connectivity of the Right Superior Medial Frontal Gyrus (ROI8) with the following brain regions: FC1: Frontal_Med_Orb_L; FC2: Frontal_Sup_Medial_R; FC3: Precuneus_L; FC4: Angular_R; FC5: Angular_L; FC6: Precuneus_R; FC7: Frontal_Mid_L; FC8: Rolandic_Oper_R; FC9: Rolandic_Oper_L. MTG.L: Left Middle Temporal Gyrus; IFGtriang.R: Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; IFGtriang.L: Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; THA.L: Left Thalamus; BNGF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; MTG.L: Left Middle Temporal Gyrus; IFGtriang.R: Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; IFGtriang.L: Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Triangular Part; THA.L: Left Thalamus; BNGF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Correlation analyzed by Spearman’s correlation. *: P < 0.05; **:P < 0.05.

4 DiscussionThis study provides a comprehensive examination of the neuroimmune profile in INRs by utilizing multimodal MRI techniques and assessing neuro-immunity characteristics. First, the study revealed significant alterations in volumes and activity indicators in certain brain regions in INRs. Second, INRs exhibited prominent immune dysregulation characterized by elevated levels of T cell senescence and activation, as well as heightened monocyte activation. Furthermore, we identified correlations between brain alterations and peripheral immune responses, as well as associations between altered endocrine factor levels and peripheral immune dysregulation in INRs, reflecting potential systemic dysregulation involving the immune and nervous systems. Interestingly, despite the significant differences observed in neuroimaging and immune markers between INRs and IRs, clinical neuro-psychological assessments did not show significant differences between the groups. This suggests that while neurological and immune dysfunction may be present, these changes may still be subclinical and not yet detectable through standard psychological assessments.

Consistent brain abnormalities were observed in the left MTG of INRs, including elevated ALFF and ReHo, as well as reduced GMV, compared to IRs. Previous research has also identified brain regions implicated in HIV-related neurological damage, with the temporal gyrus playing a crucial role in various cognitive functions and emotional processing. Dysfunction in the temporal gyrus, which is part of the attentional and memory networks, has been reported in PLWH (36, 37). A prior study with machine learning methodology identified brain regions specific to HIV diagnosis, revealing abnormal changes at both cortical and subcortical areas within the temporal and frontal lobes (21). Our study further observed that INRs exhibited atrophied GMV alongside heightened activity in the MTG, suggesting significant structural alterations in this region in INRs and a potentially compensatory functional response. Additionally, increased fALFF was observed in the left inferior frontal gyrus triangular part and left thalamus region, while decreased GMV was noted in the left lingual gyrus, left postcentral gyrus, and right ROL in INRs. Previous studies have indicated subcortical involvement and abnormal changes in frontal lobe structure and function in individuals infected with HIV (38, 39). GMV deficits have been documented in virally suppressed PWLH compared to uninfected controls in various regions of the brain, including the frontal and parietal cortices (22), the transitional cortex of the insula and cingulum, and subcortical structures such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, and hippocampus (21–24). These findings align with the alterations observed in immune reconstitution and suggest that inadequate immune reconstitution may worsen existing functional and structural brain abnormalities in individuals with HIV infection.

Diminished FC was observed between the right SFGmed and other brain regions in INRs. The FC analysis revealed a significant decrease in FC between ROI8 (right SFGmed) and brain regions including the right superior frontal gyrus, left MFG, bilateral precuneus gyrus, and bilateral angular gyrus, indicating disrupted functional integration within the brain networks of INRs. These regions play crucial roles in emotion regulation, cognitive function, attention, and memory (40, 41). The reduction in FC may suggest deficits in these cognitive processes and emotional regulation, potentially due to neuronal injury or inflammatory reactions related to HIV infection. Previous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between HIV infection and changes in brain network connectivity (42–45). Changes in the right SFGmed gyrus and left MFG, regions implicated in emotion regulation and cognitive control, have been associated with mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety in individuals with HIV infection. Dysfunction in the superior frontal and medial orbital gyrus has also been documented in PLWH (46). Changes in the bilateral occipital gyrus and bilateral angular gyrus, which are known to be involved in cognitive processes such as memory, attention, and spatial cognition, have been observed in individuals with HIV infection. Dysfunction in these areas may contribute to cognitive decline, specifically deficits in attention and memory. Previous research has indicated a correlation between HIV infection and cognitive impairment, with abnormalities in the occipital gyrus and angular gyrus being implicated in this decline (47, 48). Our results suggest a potentially heightened level of brain functional impairment in INRs. Nevertheless, further research is needed to determine the extent to which this impairment may impact cognitive function and psychiatric conditions in PLWH.

Brain structural and functional alterations associated with peripheral immunity in INRs. The immunological characteristics of peripheral blood were analyzed using techniques such as mass cytometry, Luminex and ELISA in both groups. Consistent with previous research, we found higher levels of T cell activation, senescence, and higher levels of monocyte activation in INRs (49–51). Correlation analyses also provided noteworthy results, indicating potential associations between the effects of HIV infection on brain structure, function and neuro-immunity, and endocrine factors. First, brain function and peripheral inflammatory factor levels were significantly correlated. Indicators of brain activity and functional connectivity displayed correlations with inflammatory and neurotrophic factors, including IL-1, IL-3, IL-5, IL-7, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12, IP-19, eotaxin, TNF, G-CSF, sCD40L, BDNF, and IGF-1. Previous studies have linked these cytokines or chemokines to chronic inflammation in HIV infection or their involvement in neuroprotection or neuroinflammation (52–55). The correlation between these indicators may reflect responses to HIV infection-induced neuroinflammation, neurological impairment and abnormal brain network connectivity. While our study identifies significant correlations between peripheral blood markers and brain functional alterations, it is critical to acknowledge the compartmentalized nature of marker expression in the blood and CNS. These correlations should be interpreted cautiously, as peripheral markers may not fully reflect localized CNS processes due to differences in microenvironments and the restricted permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The differences in microenvironmental conditions and compartmentalized immune responses between the CNS and peripheral blood highlight the need for further mechanistic studies. Future research with integrated CSF and peripheral blood analyses is essential to validate these findings and to elucidate the causative pathways underlying these correlations. Furthermore, advanced neuroimaging techniques targeting BBB integrity could offer additional insights into the interaction between systemic immune dysregulation and CNS alterations.

Interestingly, our study revealed a significant association between brain abnormalities and endocrine factors, of which the levels of CORT were significantly correlated with changes in fALFF and FC. HIV infection disrupts biological stress pathways, such as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis (56). Meanwhile, we identified that cortisol, a hormone involved in the HPA axis, was associated with abnormal brain function in INRs. Taken together with the previous results, we can conclude, in line with our hypothesis, that HIV in the CNS has an impact on brain structure and function in INRs, and further affects peripheral immune and inflammatory responses by modulation of hormone secretion in the HPA axis. These findings provide valuable insights for a deeper understanding of HIV-associated neuro-pathophysiologic mechanisms and suggest potential directions for future exploration of neuroprotective and therapeutic approaches.

This study demonstrates several strengths. It is the first to investigate INRs in particular, utilizing multimodal MRI to analyze brain-specific structural and functional changes. Second, the findings may provide a theoretical framework for further research on neuropsychiatric disorders in PLWH, particularly in INRs.

4.1 LimitationsThis study has some nonnegligible limitations. First, future studies should also consider investigating biological and MRI parameters in untreated HIV participants and HIV-negative participants to provide a baseline for understanding the progression of neurological impairment without the confounding effects of ART. Second, In this study, we did not collect data on the CNS-penetration-effectiveness score of the ART regimens, which limits our ability to fully assess the impact of CNS drug penetration on neurological outcomes. The analysis of brain morphology in this study only focused on grey matter volume, which represents a limitation and emphasizes the necessity for future research to explore brain morphology in greater detail. Additionally, the precision of the 1.5T MRI machine used in this study is considered inadequate, highlighting the imperative for future studies to conduct image acquisition with higher-resolution MRI machines. The multimodal MRI and mass cytometry techniques, while resource-intensive, offer valuable insights into INRs’ neuroimmune profiles. These methods may not yet be feasible for routine use, but with further refinement, they could become more accessible. Some changes in MRI or immune parameters may be infraclinical, serving as early indicators of dysfunction before clinical symptoms emerge. Another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which prevents us from developing a robust algorithm to predict neurological impairments using a small set of markers. The neurological damage observed in INRs is likely influenced by multiple factors, making it difficult to isolate specific markers at this stage. Future studies with larger cohorts will be essential to identify simplified and reliable markers for predicting brain damage in INRs, allowing for practical clinical application. While we included neuro-psychological assessment, no significant differences were observed between the INR and IR groups. This may suggest that the observed neuroimaging and immune differences may be subclinical and not yet detectable using standard psychological scales. Future studies should follow up to see whether these subclinical changes translate into clinical symptoms over time. Due to the compartmentalized expression of markers, peripheral measures may only partially represent CNS activity. Integration of cerebrospinal fluid analyses or direct CNS measures in future research would provide a more comprehensive understanding.

5 ConclusionsIn summary, we identified significant correlations between brain structural and functional alterations and peripheral immune responses in INRs. Additionally, associations were observed between altered endocrine factor levels and peripheral immune dysregulation, reflecting potential systemic dysregulation involving the immune and nervous systems. While our findings highlight the potential impact of immune dysfunction on brain structure and function, further studies are necessary to clarify the clinical relevance and to develop strategies that effectively address both viral suppression and immune reconstitution, particularly in INRs. Our study provides a novel approach to investigating the complex interplay between immune reconstitution and neurological impairment, underscoring the importance of immune status and inflammation in this context. These findings not only contribute to our understanding of the pathophysiology of HIV-related neuropathy, but also offer valuable insights for the customization of therapeutic interventions for INRs.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Youan Hospital, Capital Medical University (2023/057). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from primarily isolated as part of your previous study for which ethical approval was obtained. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributionsYZ: Writing – original draft. JJ: Writing – original draft. LZ: Writing – original draft. MC: Writing – review & editing. GS: Writing – review & editing. YM: Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – review & editing. XC: Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing. XL: Writing – review & editing. ZL: Writing – review & editing. TZ: Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Beijing Research Ward Excellence Program (BRWEP2024W042180103 to YZ), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072271 to TZ, 82241072 to TZ, 82072294 to ZL), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7222095 to YLZ, 7222091 to YZ), the High-level Public Health Technical Personnel Construction Project (2022-1-007 to TZ), and the Beijing Key Laboratory for HIV/AIDS Research (BZ0089 to TZ), the High-level Public Health Specialized Talents Project of Beijing Municipal Health commission(2022-02-20 to ZL), the Peak Talent Program of Beijing Hospital Authority (DFL20191701 to TZ), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFC0122601), the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2022-1-1151 to TZ), the Research and Translational Application of Clinical Characteristic Diagnostic and Treatment Techniques in Capital City (Z221100007422055 to TZ), Beijing research center for respiratory infectious diseases project(BJRID2024-001 to YLZ), the Beijing Hospitals Authority Innovation Studio of Young Staff Funding Support (2021037 to YZ).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1452532/full#supplementary-material

References1. Rb-Silva R, Goios A, Kelly C, Teixeira P, Joao C, Horta A, et al. Definition of immunological nonresponse to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2019) 82:452–61. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002157

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Bono V, Augello M, Tincati C, Marchetti G. Failure of cd4+ T-cell recovery upon virally-effective cart: an enduring gap in the understanding of hiv+ Immunological non-responders. New Microbiol. (2022) 45:155–72.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

3. Kaufmann GR, Perrin L, Pantaleo G, Opravil M, Furrer H, Telenti A, et al. Cd4 T-lymphocyte recovery in individuals with advanced hiv-1 infection receiving potent antiretroviral therapy for 4 years: the swiss hiv cohort study. Arch Internal Med. (2003) 163:2187–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2187

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, Perrin L, Opravil M, Vernazza P, et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of cd4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microl in hiv type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis: An Off Publ Infect Dis Soc America. (2005) 41:361–72. doi: 10.1086/431484

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Gutierrez F, Padilla S, Masiá M, Iribarren JA, Moreno S, Viciana P, et al. Clinical outcome of hiv-infected patients with sustained virologic response to antiretroviral therapy: long-term follow-up of a multicenter cohort. PloS One. (2006) 1:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000089

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Kelley CF, Kitchen CM, Hunt PW, Rodriguez B, Hecht FM, Kitahata M, et al. Incomplete peripheral cd4+ Cell count restoration in hiv-infected patients receiving long-term antiretroviral treatment. Clin Infect Dis: An Off Publ Infect Dis Soc America. (2009) 48:787–94. doi: 10.1086/597093

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. van Lelyveld SF, Gras L, Kesselring A, Zhang S, De Wolf F, Wensing AM, et al. Long-term complications in patients with poor immunological recovery despite virological successful haart in dutch athena cohort. AIDS (London England). (2012) 26:465–74. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f32f8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. O’Connor JL, Smith CJ, Lampe FC, Hill T, Gompels M, Hay P, et al. Failure to achieve a cd4+ Cell count response on combination antiretroviral therapy despite consistent viral load suppression. AIDS (London England). (2014) 28:919–24. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000165

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. He L, Pan X, Dou Z, Huang P, Zhou X, Peng Z, et al. The factors related to cd4+ T-cell recovery and viral suppression in patients who have low cd4+ T cell counts at the initiation of haart: A retrospective study of the national hiv treatment sub-database of Zhejiang Province, China, 2014. PloS One. (2016) 11:e0148915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148915

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Kroeze S, Ondoa P, Kityo CM, Siwale M, Akanmu S, Wellington M, et al. Suboptimal immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy with sustained hiv suppression in sub-saharan africa. AIDS (London England). (2018) 32:1043–51. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000001801

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Han WM, Ubolyam S, Apornpong T, Kerr SJ, Hansasuta P, Gatechompol S, et al. Characteristics of Suboptimal Immune Response after Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy among People Living with Hiv with a Pre-Treatment Cd4 T Cell Count <200 Cells/Mm(3) in Thailand. J Virus Eradication. (2020) 6:100005. doi: 10.1016/j.jve.2020.100005

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR Jr., Baker JV, Calmy A, Duprez D, La Rosa A, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with hiv infection. J Infect Dis. (2010) 201:1788–95. doi: 10.1086/652749

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Tenorio AR, Zheng Y, Bosch RJ, Krishnan S, Rodriguez B, Hunt PW, et al. Soluble markers of inflammation and coagulation but not T-cell activation predict non-aids-defining morbid events during suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis. (2014) 210:1248–59. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu254

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Psomas C, Younas M, Reynes C, Cezar R, Portalès P, Tuaillon E, et al. One of the immune activation profiles observed in hiv-1-infected adults with suppressed viremia is linked to metabolic syndrome: the activih study. EBioMedicine. (2016) 8:265–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.008

留言 (0)