Coronary angioma is characterized as a dilated segment of the coronary artery that exceeds 1.5 times the diameter of adjacent normal segments (1). Based on current literature, the prevalence of large coronary aneurysms ranges from 0.02% to 0.2% (2). However, the prevalence of large coronary aneurysms measuring 5 cm or more in diameter is even lower, less than 0.02% (1–3). The right coronary artery is the most commonly affected, accounting for 40%–70% of cases, followed by the circumferential artery (23%) and the anterior descending branch (32%) (1, 2, 4). Involvement of all three vessels or the left coronary trunk is rare.

2 Case presentationThis case report presents the clinical details of a 43-year-old male patient who developed a cough and sneezing following a recent cold. Although the cold symptoms improved with self-administered medication, the patient experienced wheezing and paroxysmal dyspnea after physical activity. An electrocardiography(ECG) at a local hospital revealed rapid ventricular rate atrial fibrillation with variable conduction.

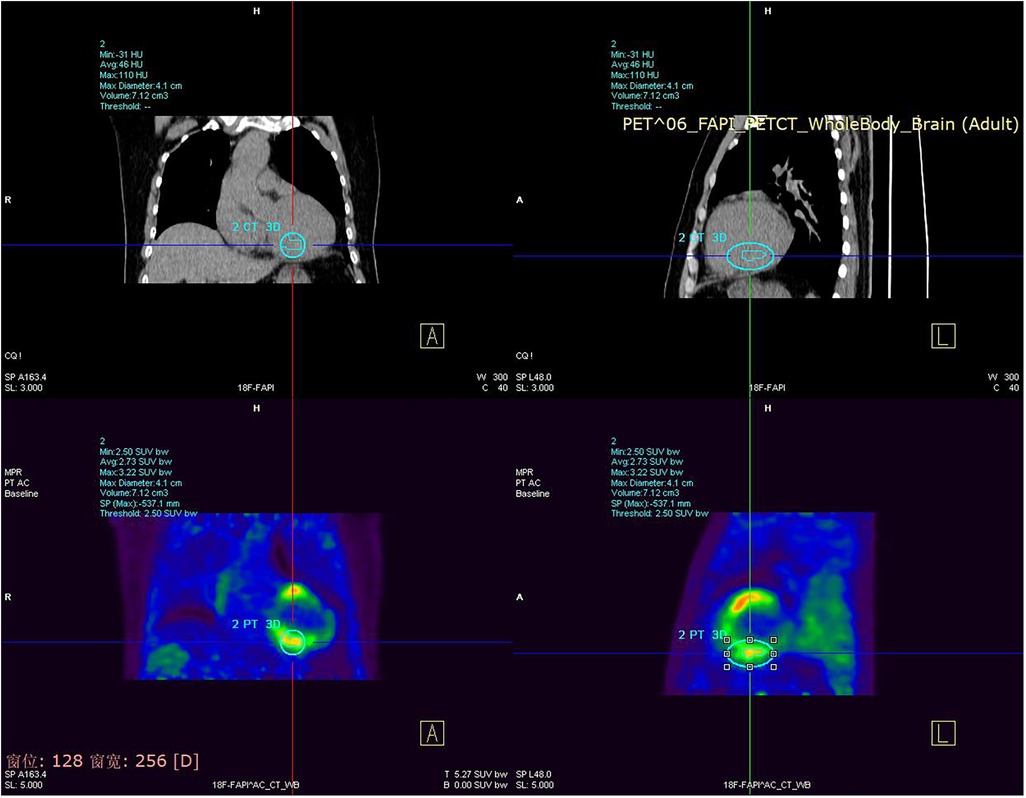

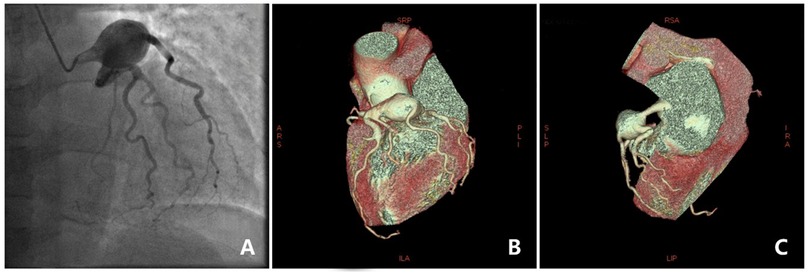

The cardiac ultrasound indicated that the LVEF was 38% and the left atrium and ventricle were enlargement with weakened ventricular septal motion. Moderate mitral and mild aortic and pulmonary regurgitation were also noted. The patient also displayed a troponin sensitivity of 0.023 ug/L. Based on these findings, the local hospital suspected viral myocarditis. The patient was referred to our cardiovascular department for further assessment. The patient's NT pro-BNP level was measured at 1,169 pg/ml, and myocardial nuclide imaging (PET) revealed increased fibroblast activation protein inhibitors(FAPI) uptake throughout the left ventricle and right atrium (Figure 1), supporting a diagnosis of myocarditis. The patient received symptomatic treatment, including hormone anti-inflammatory therapy, nutritional support for myocarditis, and gamma globulin therapy. However, these interventions provided limited relief from wheezing. Coronary angiography showed a left coronary dominant type, with no obvious stenosis in the left main trunk but a 2.7 × 2.3 cm aneurysm in the distal part of the left main trunk. No stenosis was observed in the anterior descending branch, circumflex branch, or right coronary artery (Figure 2). Autoimmune workup, including ANA, anti-dsDNA, ENA antibody profile, and ANCA, returned negative results, ruling out autoimmune causes of the aneurysm. Given the giant aneurysm in the left main trunk, myocarditis, and heart failure with intermediate ejection fraction, open-heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, partial tumor resection, and coronary artery bypass grafting was recommended. However, due to the high risk, the patient and family opted for conservative treatment. As intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was not performed during coronary angiography, antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy was not initiated. Instead, the patient was prescribed atorvastatin 20 mg nightly and metoprolol succinate sustained-release 47.5 mg daily.

Figure 1. Myocardial nuclide imaging (PET) revealed increased FAPI uptake throughout the left ventricle and right atrium.

Figure 2. Coronary angiography image and 3D reconstruction. (A) Coronary angiography showed a large aneurysm. (B,C) 3D reconstruction of an aneurysm in a coronary artery.

The patient was closely monitored at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post-discharge. During follow-up, the coronary aneurysm showed no significant changes, and the patient reported slight improvement in dyspnea, though other symptoms and physical signs remained stable.

3 DiscussionThe exact cause of coronary aneurysm formation remains unclear. However, studies have shown that matrix metalloproteinases play a role in the pathogenesis of CAA formation by increasing the breakdown of proteins in the extracellular matrix (5, 6). These enzymes have the ability to degrade various components of the arterial wall matrix and are found in higher concentrations in aneurysms. There is no consensus on the definition of a giant coronary aneurysm. In most literature, it is considered a giant coronary aneurysm if the dilation of the coronary artery is more than 1.5 times the diameter of adjacent normal reference vessels or if the vessel diameter is directly greater than 20 mm (7–9).

Coronary aneurysms can have several etiologies, including atherosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, and Kawasaki disease (9, 10). In this case, the patient's autoimmune screening and coronary angiography findings were negative, suggesting a high likelihood of congenital origin. Coronary aneurysms can present with a range of clinical manifestations, such as asymptomatic chest pain, chest tightness, and pericardial tamponade (11). Initially, the patient did not experience any symptoms but was admitted to the hospital this time due to wheezing and dyspnea after catching a cold. Myocardial nuclide imaging was performed to consider myocarditis, but the symptoms did not improve significantly with treatment. Subsequent coronary angiography revealed the presence of a large coronary aneurysm.

Thrombus formation occurs in coronary aneurysms due to slow blood flow and platelet activation. To better assess aneurysm condition, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is recommended when a coronary aneurysm is detected via angiography. In the case with thrombosis, coagulation function, thromboelastography (TEG), and platelet function tests are advised. With timely anticoagulation or antithrombotic therapyare necessary. According to a 2021 study by Tuncay Taskesen, patients without symptoms, coronary occlusion, or thrombosis may not require specialized treatment (12). Additionally, Cihan Ozturk reported a case of an asymptomatic patient with a right coronary aneurysm who remained symptom-free for many years (13). However, for patients with obstructive coronary artery disease symptoms or myocardial ischemia due to embolization, surgical intervention is appropriate. Surgical options include interventional therapy, aneurysm excision, ligation, or coronary artery bypass surgery (2). In a notable 2024 case report by Najdat Bazarbashi, a patient with a large coronary aneurysm was successfully treated with a combination of stent placement and coil embolization (14). For cases involving multiple vessel disease, left main coronary artery aneurysm, or complications like fistula, compression, or rupture, surgical treatment is typically indicated. However, our patient opted for conservative management, which led to symptom alleviation over follow-up. If symptoms worsen, surgical or interventional treatments may become necessary, though surgical costs are high, and clinical evidence on specific prognostic outcomes is limited.

4 ConclusionLeft main congenital coronary aneurysms are exceedingly rare. Proper diagnosis and treatment require assessment of thrombus presence within the aneurysm, along with evaluation of coagulation and platelet function to guide anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy. For surgical decision-making, factors such as aneurysm location, size, arterial wall condition, and overall patient health should be carefully considered to select an appropriate treatment approach.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statementWritten informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsPX: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statementThe author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Kawsara A, Nunez Gil IJ, Alqahtani F, Moreland J, Rihal CS, Alkhouli M. Management of coronary artery aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11:1211–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.041

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Pham V, Hemptinne Q, Grinda JM, Duboc D, Varenne O, Picard F. Giant coronary aneurysms, from diagnosis to treatment: a literature review. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 113(1):59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2019.10.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Scarpa J, Zhu A, Morikawa NK, Chan JM. Perioperative management of giant coronary artery aneurysm. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2023) 37(10):2040–5. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2023.05.030

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Baman TS, Cole JH, Devireddy CM, Sperling LS. Risk factors and outcomes in patients with coronary artery aneurysms. Am J Cardiol. (2004) 93(12):1549–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.011

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Wang E, Fan X, Qi W, Song Y, Qi Z. A giant right coronary artery aneurysm leading to tricuspid stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 108:e145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.01.078

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Schafigh M, Bakhtiary F, Kolck UW, Zimmer S, Greschus S, Silaschi M. Coronary artery aneurysm rupture in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa. JACC Case Rep. (2022) 4(22):1522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2022.06.020

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Rizk S, Amin W, Hamza H, Said K, Said GE. Pseudo-normalization of a coronary artery aneurysm detected by IVUS. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. (2017) 3:e201732.

8. De Hous N, Haine S, Oortman R, Laga S. Alternative approachfor the surgical treatment of left main coronary arteryaneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 108:e91–3. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.12.035

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Mata KM, Fernandes CR, Floriano EM, Martins AP, Rossi MA, Ramos SG. Coronary artery aneurysms: an update. In: Lakshmanadoss U, editor. Novel Strategies in Ischemic Heart Disease. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech (2012). p. 381–404. doi: 10.5772/32331

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Shaefi S, Mittel A, Klick J, Evans A, Ivascu NS, Gutsche J, et al. Vasoplegia after cardiovascular procedures-pathophysiology and targeted therapy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2018) 32(2):1013–22. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.10.032

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Busse LW, Barker N, Petersen C. Vasoplegic syndrome following cardiothoracic surgery-review of pathophysiology and update of treatment options. Crit Care. (2020) 24:36. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2743-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Taskesen T, Osei K, Ugwu J, Hamilton R, Tannenbaum M, Ghali M. Coronary artery aneurysm presenting as acute coronary syndrome: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 52(2):683–8. doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02418-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Bazarbashi N, Mendelson C, Rogers T, Hashim HD, Satler LF, Waksman R, et al. Coronary vein graft aneurysm treatment using coils. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2024) 17(13):1612–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2024.04.037

留言 (0)