Known for its rapid growth and sustainability, bamboo is an essential resource worldwide (especially in Asia). Phyllostachys heteroclada Oliver, known as fishscale bamboo, is a crucial waterlogging-tolerant and industrial bamboo species native to China. It plays an important role in riparian zone restoration, bamboo shoots, and handicraft production and serves as a vital food source for wild giant pandas (Jing et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2024; Shi and Chen, 2022). The culms are the primary economic component of bamboo; however, culm diseases significantly impact bamboo wood quality, leading to considerable ecological and financial losses (Huang L. et al., 2023). Although numerous culm diseases have been reported, there is a lack of in-depth studies (Huang L. et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2024). Notably, major culm diseases such as bamboo blight and bamboo witches’ broom are receiving increased attention, including investigations into their pathogenic molecular mechanisms (Li et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2024). For example, the whole genome of the bamboo blight pathogen, Arthrinium phaeospermum, has been published, identifying key pathogenic factors such as the ApCE12 and ApCE22 effectors and Ctf1β cutinase (Li et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2022). Among these diseases, rhombic-spot disease is recognized as one of the most significant threats to fishscale bamboo, with Neostagonosporella sichuanensis being the most commonly reported pathogen (Yang, 2019). N. sichuanensis primarily infects fishscale bamboo branches and culms through the stomatal apparatus and various wounds (Yang, 2019). Numerous pycnidia and ascostromata can be observed at infection sites, with ascostromata being particularly abundant, continuously released from November through April of the following year (Liu et al., 2022). During the disease spread period from May to October, N. sichuanensis mainly persists in the branches and culms of the host in the form of mycelia and conidia (Liu et al., 2022).

Plant cell walls, consisting of complex polysaccharides, which primarily include cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, form an effective physical barrier against fungal invasion (Underwood, 2012). Xylan, a hemicellulose characterized by a β-1,4-linked xylose backbone, is the predominant hemicellulose that exists in both monocots and dicots. It is integral to plant cell wall structure by providing flexibility and strength through its interactions with cellulose and lignin (Rennie and Scheller, 2014). Xylan-degrading enzymes, known as xylanases, are necessary for the full degradation of hemicellulose (Bhardwaj et al., 2019). Xylanases mainly belong to glycoside hydrolase families 10 and 11 according to their molecular weight and catalytic domains (Bhardwaj et al., 2019). GH10 xylanases generally have higher molecular weights and broader substrate specificities, whereas GH11 xylanases are smaller and exhibit better catalytic effectiveness on linear xylan chains (Liu et al., 2021).

Xylanases are crucial in the pathogenicity and infection processes of various fungal pathogens. However, reports on the contribution of GH10 family xylanases to fungal pathogenicity remain limited. For instance, the GH10 xylanase RcXYN1 from Rhizoctonia cerealis has been found to exacerbate disease severity during wheat infections (Lu et al., 2020). Additionally, two GH10 xylanases have been identified from the genome of Botrytis cinerea B05.10, but relevant experiments have not yet determined the contributions of these xylanases to the pathogenicity of this fungus (García et al., 2017). In contrast, there is considerable literature on the involvement of GH11 xylanases in fungal pathogenicity. GH11 family xylanases enable fungi to penetrate the plant cell wall by degrading xylan, which facilitates tissue colonization and nutrient acquisition for fungal growth (Wang et al., 2021). Beyond their role in cell wall degradation, GH11 family xylanases contribute to fungal development, reproduction, and virulence. For instance, in Magnaporthe oryzae, the rice blast fungus, the GH11 family xylanase MoXYL1A is crucial for conidiation, appressorium maturation, and virulence, underscoring its importance in effective host colonization (Shabbir et al., 2022). Furthermore, some xylanases function as protein elicitors activating PAMPs-triggered immunity (PTI) during host-pathogen interactions, triggering host defense responses that lead to cell necrosis (Enkerli et al., 1999). For example, the xylanase BcXyn11A from Botrytis cinerea can be recognized by plants as PAMPs and elicits plant defenses (Frías et al., 2019). This necrosis-inducing effect not only disrupts local cell integrity, providing an entry point for fungal invasion, but also suppresses nearby immune responses, creating an environment conducive to nutrient acquisition and sustained infection (Derbyshire and Raffaele, 2023). These findings emphasize that GH11 family xylanases are important components of the sophisticated strategies employed by fungal pathogens to penetrate and develop infections in their plant hosts.

Screening for xylanase genes within fungal genomes enables the systematic identification of xylanase genes potentially implicated in plant cell wall degradation, facilitating further studies through gene knockout or overexpression techniques to validate their roles in pathogenicity. Moreover, this method helps elucidate the diversity and evolutionary history of xylanase gene families, providing insights into their contribution to fungal adaptability and virulence. For example, identifying and annotating carbohydrate-active enzymes(CAZy) enhanced the comprehension of the genomic structure of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) in Fusarium virguliforme. Sequence and structural investigations of FvXyn11A and FvXyn11B revealed conserved residues facilitating XIP-I inhibition, with both xylanases expressed during soybean root infection (Chang et al., 2016). Comparative genomics investigations indicated that the Verticillium dahliae genome contains a family of six xylanases, with VdXyn4 facilitating the degradation of the plant cell wall and contributing to the pathogenicity of V. dahliae (Wang et al., 2021).

The genome of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis has been released, detailing the quantity and distribution of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) within it (Liu et al., 2024). Prior research demonstrated that N. sichuanensis exhibits strong xylan degradation activity, suggesting that the pathogen may employ hemicellulose degradation to penetrate plant cell walls during infection (Liu et al., 2024). Despite the well-established importance of xylanases in fungal pathogenicity, their specific role in the virulence of N. sichuanensis remains unknown. In this study, we comprehensively examined the involvement of GH11 family xylanases in the pathogenicity of N. sichuanensis in plant systems. The principal aims were to (1) determine whether these xylanases are secreted proteins and examine their location in plant cells; (2) evaluate the relationship between the enzymatic activity and cell necrosis-inducing activity; (3) determine whether N. sichuanensis xylanases are up-regulated during pathogen infection; and (4) investigate the contribution of xylanases to N. sichuanensis virulence.

2 Materials and methods 2.1 Plants, strains, and culture conditionsThe wild-type strain Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 was acquired from the Culture Collection at Sichuan Agricultural University (SICAUCC) and activated on PDA medium at 25°C for 7 days and then subcultured on fresh PDA medium at 25°C for 30 days. Nicotiana benthamiana was cultivated at 25°C under a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle in an artificial climate incubator. Healthy one-year fishscale bamboo seedlings were cultivated at 25°C under a 12-h light and 12-h dark cycle in an artificial climate incubator after transplanted from Zhougongshan Town (103°2′59.87″E, 29°50′8.56″N) in Ya’an City, Sichuan Province, China, to the Chengdu Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (103°85′73.17″E, 30°70′32.61″N) in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China.

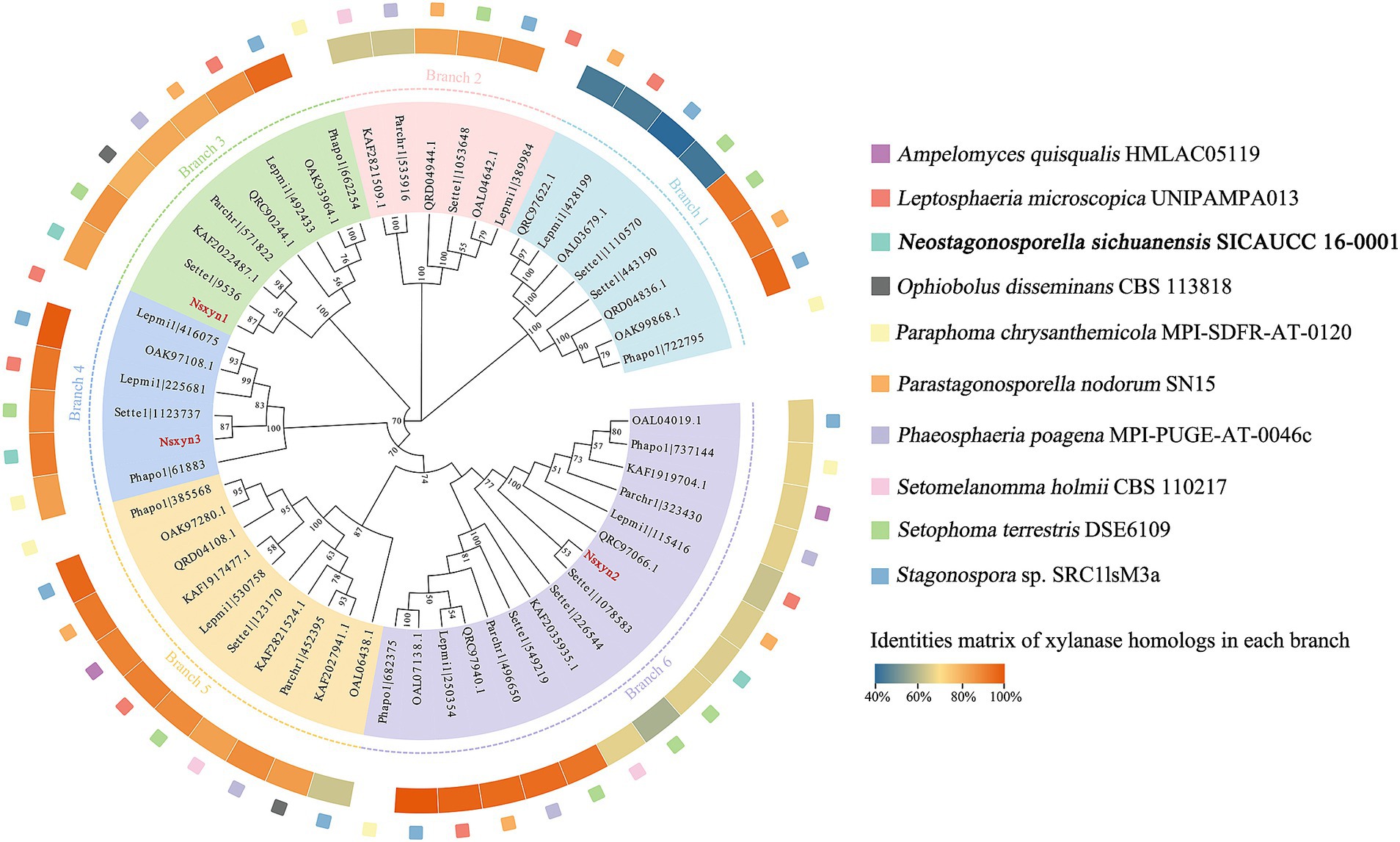

2.2 Identification and bioinformatics analysis of GH11 xylanase family proteins in Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 genomeXylanase family proteins were identified by querying the HMM profile of the Glyco_hydro_11 (GH11) domain (Pfam ID: PF00457) against the Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 genome and nine other phaeosphaeriacous species (Ampelomyces quisqualis, Leptosphaeria microscopica, Ophiobolus disseminans, Paraphoma chrysanthemicola, Parastagonospora nodorum, Phaeosphaeria poagena, Stagonospora sp., Setomelanomma holmii, and Setophoma terrestris) using HMMER v3.4 (Potter et al., 2018) with an E-value threshold of ≤1 × 10−5. The returned hits with scores > 30 were selected. The genome sequences used for the xylanase proteins screening of four strains, Leptosphaeria microscopica, Paraphoma chrysanthemicola, Phaeosphaeria poagena, and Setophoma terrestris were downloaded from the JGI Genome Portal (Nordberg et al., 2014), and the genome sequences of the remaining five species were downloaded from the NCBI Genome (Sayers et al., 2022). Subsequently, these candidate proteins were searched for the Glutamic acid enzymatic activity sites and conserved glycoside hydrolase families 11 motifs using the ProSITE webserver (Sigrist et al., 2012). These sequences without enzyme active sites were discarded. The remaining sequences were submitted to SignalP v5.0 (Almagro Armenteros et al., 2019), TMHMM v2.0 (Krogh et al., 2001), BIG-PI Fungal Predictor (Eisenhaber et al., 2004), and WoLF PSORT (Horton et al., 2007) for secretory protein prediction. Protein sequences possessing a signal peptide, devoid of the transmembrane region and anchor location, and extracellular subcellular localization were identified as xylanase proteins and analyzed further. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with these selected xylanase proteins using MEGA v11 (Tamura et al., 2021) with the neighbor-joining method and visualized through Evolview v3.0 webserver (Subramanian et al., 2019). ClustalX v2.0 (Larkin et al., 2007) and ESpriPT3.0 webserver (Robert and Gouet, 2014) performed multiple sequence alignment. SOMPA (Geourjon and Deléage, 1995) and SWISS-MODEL web tools (Waterhouse et al., 2024) were used to predict the secondary and tertiary structures with the AlphaFold v2 method, respectively. The quality of the predicted models was assessed by SAVES v6.1 (Bowie et al., 1991; Lüthy et al., 1992; Colovos and Yeates, 1993; Laskowski et al., 1996) and Qmean (Benkert et al., 2011).

2.3 Total RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and cloning of CDS full-length of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 genesFresh Neostagonosporella sichuanensis mycelia were collected for total RNA extraction utilizing the Quick RNA Isolation Kit (Huayueyang, Beijing, China). The concentration and purity of RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The isolated RNA was preserved at-80°C for subsequent study. High-quality total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time; Takara, Beijing, China). Only two candidate xylanase genes (Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2) were successfully cloned from the cDNA of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001. Primers (Supplementary Table S1) were designed by Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The target fragments were amplified using 2 × TransTaq® High Fidelity (HiFi) PCR SuperMix II (−dye) (TRANS, Beijing, China) and purified using a Universal DNA Purification Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). Then, they were connected to pMD™-19 T vectors (Takara, Beijing, China), respectively, by the manufacturer’s guidelines. The ligation mixture was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α cells, which were then spread onto antibiotic-containing Luria-Bertani (LB) agar. Positive clones were screened by colony PCR and verified by sequencing.

2.4 Recombinant protein expression optimization, purification, and enzyme activity assays of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 fragments (Amplified primers were in Supplementary Table S1), devoid of the predicted signal peptides and stop codons, were introduced into the pET-32a plasmid at the EcoR I and Xho I sites, respectively, and subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) for expression. To get adequate soluble proteins for subsequent analysis, expression conditions were optimized by inducing with IPTG at various concentrations and temperatures, followed by an analysis of expression levels by SDS-PAGE (Zhao et al., 2022). Large-scale protein production was carried out under optimal conditions, and the His6-tagged protein was purified utilizing a His-tag protein purification kit (Reductant&Chelator-resistant; Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Two Glu residues of the Nsxyn1rec/Nsxyn2rec mutant were replaced with Lys residues utilizing the Hieff Mut™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) to eliminate xylanase activity of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2. Following verification through sequence alignment, the Nsxyn1rec and Nsxyn2rec mutants were expressed under optimal conditions and purified as described above. Protein concentrations were then determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

For qualitative analysis, recombinant proteins were introduced to wells containing a medium with hardwood xylan (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) as the exclusive carbon source (Meddeb-Mouelhi et al., 2014). After 2 h of incubation, the medium was treated with 1% Congo red solution for 1 h and then eluted with 1 mol/L NaCl solution for 3 h. Hydrolytic zones were then examined using sterile eluents as negative controls. Xylanase activity was quantified by a modified DNS (dinitrosalicylic acid) assay (Fu et al., 2019) with some modifications. A mixture of 90 μL of 1% hardwood xylan solution (pH 6.5) and 10 μL of recombinant xylanase solution was incubated in PCR tubes at 45°C for 30 min. Subsequent to the reaction, 100 μL of DNS solution was immediately added, and the mixture was heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min before cooling to ambient temperature. The negative controls comprised 90 μL of 1% xylan solution (pH 6.5) and 10 μL of heat-inactivated recombinant xylanase. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.5 Assessment of necrotic activity of purified Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 xylanase proteins in Nicotiana benthamianaTo assess the potential necrotic activity of the purified proteins, leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana were infiltrated with 10 μmol/L of each purified xylanase protein using a needleless syringe. The infiltration sites were marked, and the plants were incubated under controlled conditions at 25°C under a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle. Leaf tissue was observed for the development of necrosis throughout 5 days post infiltration, with leaves infiltrated with buffer only used as negative controls.

2.6 qRT-PCR analysisThe transcript levels of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 at different infection times in fishscale bamboo were quantified by qRT-PCR on a CFX96™ real-time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Specific primers for amplification were designed according to the coding regions of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2, with the Neostagonosporella sichuanensis elongation factor 1 alpha gene as an internal control (the coding sequence is detailed in Supplementary Table S2). The qRT-PCR reaction setup and conditions followed those described by Liu et al. (2019). A no-template control (ddH2O) was included. The infection timepoint exhibiting the lowest expression served as the baseline (assigned a value of 1.0). Relative expression levels were calculated utilizing the 2-∆∆Ct method (Ritter and Schulz, 2004; Zhu et al., 2015). Each qRT-PCR experiment was performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad version 8.4.2, with statistical significance assessed by unpaired Student’s t-test.

2.7 Signal peptides secretion function detection of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2To detect whether the signaling peptides of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins possess secretory functions, the relevant signaling peptide sequences were inserted into the pSUC2 vector and transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae YTK12 competent cells, which are lacking invertase secretion. Transformants were selected on CMD-W medium and cultured at 30°C for 48 h. Positive colonies were transferred to the YPRAA medium to evaluate the secretory activity and incubated at 30°C for 48 h. The CMD-W and YPRAA mediums were prepared according to Huang’s method (Huang C. P. et al., 2023). The secretory function was further confirmed by staining with 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC), as described by Yin et al. (2018). The appearance of a red precipitate indicated successful secretion of the expressed proteins.

2.8 Subcellular localization assays and transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2To investigate the subcellular localization of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins in planta and assess their necrosis-inducing activity, the coding sequences of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 (without stop codons) were ligated to the 5′ end of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene, driven by the MAS promoter (Amplified primers were in Supplementary Table S1). These constructs were then inserted into the pCAMBIAsuper1300-EGFP vector at the KpnI and XbaI restriction sites to generate recombinant expression vectors, pCAMBIAsuper1300:Nsxyn1-EGFP and pCAMBIAsuper1300:Nsxyn2-EGFP.

Onion epidermal cells and Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts were used for subcellular localization analysis. Disinfected onion inner epidermal slices (~1 cm2) were incubated in Agrobacterium suspensions (GV3101) containing either Nsxyn1-EGFP, Nsxyn2-EGFP, or the empty pCAMBIAsuper1300-EGFP vector as a control, for 30 min. The epidermal slices were then placed on MS medium and incubated at 25°C under a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle. Fluorescence was observed 24 h later using an Ultra-High Resolution Confocal Microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), with excitation at 488 nm. Moreover, protoplasts were prepared from the leaves of 3–4 week-old A. thaliana seedlings for protoplast localization. The Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 plasmids were co-transformed with an SV40 NLS plasmid into the protoplasts via PEG4000-mediated transformation. After overnight incubation at 23°C under low light conditions, the protoplasts were centrifuged at 400 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Fluorescent signals were visualized using a confocal laser microscope (FV1000). Fluorescence detection parameters were GFP excitation at 488 nm, mCherry excitation at 561 nm, and chloroplast autofluorescence at 640 nm.

For necrosis induction assays, Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (pSoup-19) harboring the Nsxyn1 or Nsxyn2 constructs was infiltrated into the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. Empty vector pCAMBIAsuper1300-EGFP-MGS served as a negative control. After 3 days of incubation at 25°C with a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle, the infiltrated leaves were collected, and the development of necrosis was assessed.

2.9 Generation of gene deletion mutants and complementationNsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 mutants were created via targeted gene disruption using homologous recombination. Gene-specific left, and right flanking regions (1,000–1,500 bp) along with the hygromycin resistance flanking region were amplified and inserted into the pCE-Zero vector (detailed primers are in Supplementary Table S1). Using the method described by Liang et al. (2024), the knockout construct was introduced into Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 via protoplast transformation. Successful mutant generation was verified by PCR analysis.

For the complementation of mutants, the full-length Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 genes, including their native promoter regions, were inserted into the pEASY-NeoR vector, which contains a neomycin resistance (NeoR) marker (detailed primers are in Supplementary Table S1). These constructs were reintroduced into the respective mutant strains. Complemented strains were selected on G418-containing mediums, and successful integration was verified by PCR.

2.10 Phenotypic and virulence analysis of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 gene deletion mutants and complemented strainsTo assess the impact of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 deletions on fungal development and stress adaptation, a comprehensive phenotypic analysis was conducted on the gene deletion mutants, complemented strains, and wild-type controls. Growth rates were determined by measuring colony diameters on a PDA medium incubated at 25°C over a 30-day incubation period. Sporulation was quantified by counting conidia produced on the PDA plates after 30 days using a hemocytometer. Spore morphology was examined under a light microscope. At the same time, conidial germination rates were assessed by incubating conidia in sterile distilled water for 24 h at 25°C, followed by counting germinated spores under the microscope.

Oxidative and osmotic stress assays were performed to evaluate stress tolerance. Strains were grown on a PDA medium supplemented with 10 μmol/L Congo red for oxidative stress and either 1 mol/L NaCl or 0.02% SDS for osmotic stress. Colony growth was monitored by measuring the diameters after a 30-day incubation period. To evaluate the capacity of these strains to degrade primary cell wall components, they were cultured on the PDA mediums containing 1% (w/v) cellulose, xylan, or pectin as the sole carbon source. Enzyme activity was quantified by measuring the diameter of clear zones after Congo red staining, providing insight into the ability to degrade cell wall polysaccharides of these strains.

For virulence assessment, Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 gene deletion mutants, complemented strains, and the wild-type strains were cultured on PDA at 25°C for 30 days. Single conidia were isolated and transferred to fresh PDA medium for 15-day incubation. Conidia were harvested and diluted to a concentration of 1 × 106 conidia/mL in sterile distilled water. Surface-sterilized host plant leaves were wounded with a sterile needle, and 10 μL of the conidial suspension was applied to each wound. Inoculated plants grow at 25°C with 80% relative humidity. Disease symptoms were monitored daily. Lesion sizes were recorded at 30 days post-inoculation to determine virulence. The assays were repeated in triplicate in each treatment.

Data analysis was performed using One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s multiple range test in SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Shanghai, China). Graphical data visualization was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.4.2 to illustrate significant differences in disease indices among strains.

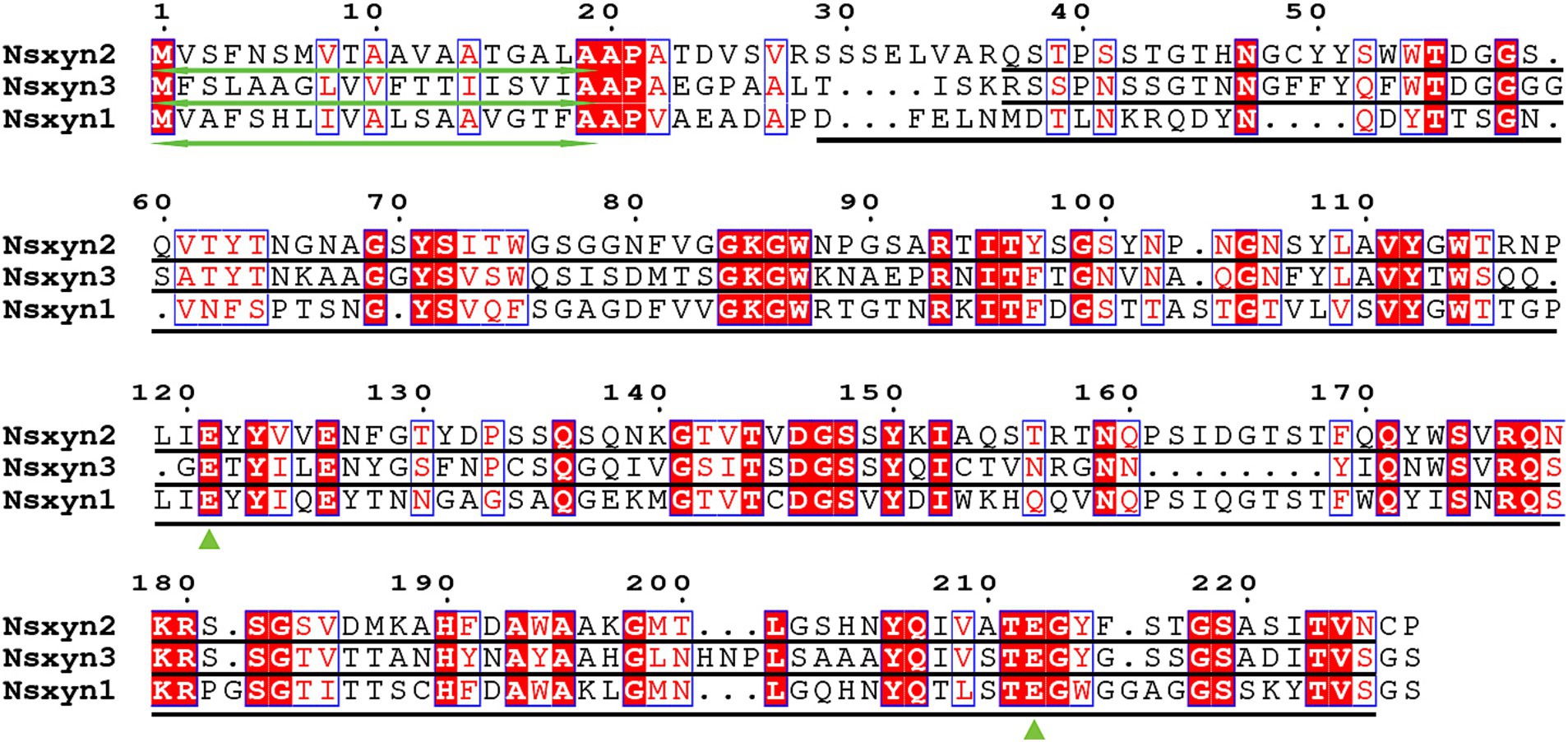

3 Results 3.1 Identification of GH11 domain-containing xylanases in Neostagonosporella sichuanensisThree xylanases containing GH11 domain proteins (Nsxyn1-Nsxyn3) were identified in the genome of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 through bioinformatics analysis. These xylanases were identified as secreted proteins with signaling peptides, lacking transmembrane regions and GPI-anchor signals (Supplementary Table S3). The same screening method predicted 51 xylanase proteins from nine other phaeosphaeriacous species (Supplementary Table S3). These xylanase proteins and Nsxyn1-Nsxyn3 were subjected to phylogenetic analysis with the neighbor-joining method. The generated phylogenetic tree clustered the proteins into six distinct clades, designated Branch1 to Branch6, widely represented among the analyzed phaeosphaeriacous species. Most xylanases exhibited relatively higher sequence similarity within the same branches, indicating a degree of conservation within the Phaeosphaeriaceae family (Figure 1). However, sequence alignment analysis revealed low homology between the GH11 domains of the three xylanases from N. sichuanensis, with pairwise identities of 44.04% between Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2, 29.44% between Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn3, and 47.67% between Nsxyn2 and Nsxyn3 (Figure 2). Despite the low sequence homology, all three xylanases shared two conserved catalytic sites associated with glutamic acid residues (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic analysis of GH11 xylanase proteins between Neostagonosporella sichuanensis and nine other phaeosphaeriacous species constructed using the neighbor-joining method. We select the first sequence in each branch in a counterclockwise direction for sequence similarity comparison with other sequences within the branch. Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, and Nsxyn3 are highlighted in bold red. In the phylogenetic tree, nodes with support values below 50% were not displayed.

Figure 2. Sequence alignments were performed for Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2 and Nsxyn3. Numbers denote the positions of the amino acid residues. Bidirectional green arrows mark signal peptides, while black lines represent GH11 domains. Green triangles highlight the two conserved glutamate enzymatic activity sites. The alignment sequences of each site are highlighted with red characters on a white background with blue frames when the amino acid similarity in the same column is greater than 0.7 and highlighted with white characters on a red background with blue frames when they are strictly conserved in the column. Amino acids with a similarity of less than 0.7 in the same column are highlighted with black characters on a white background.

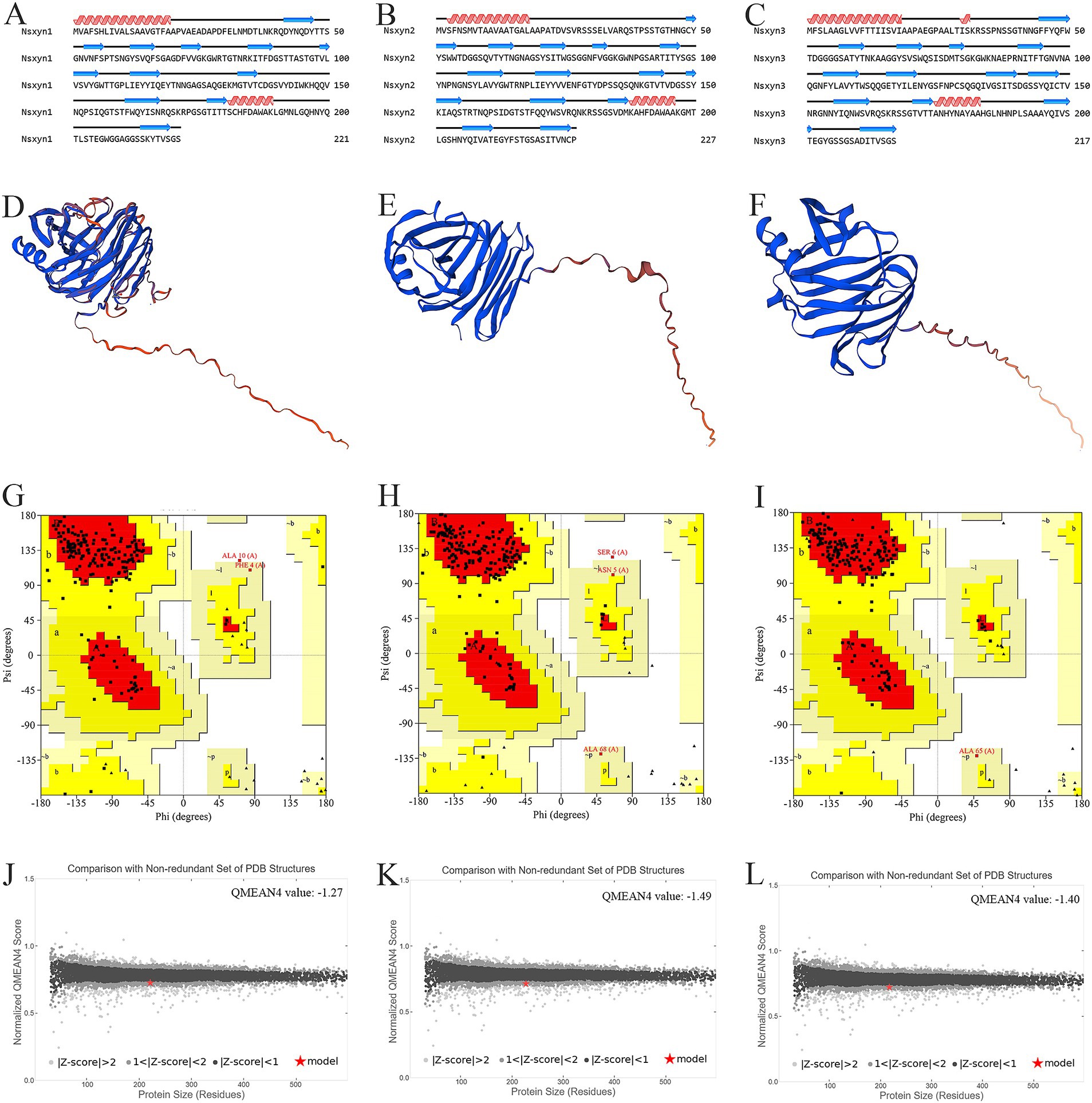

3.2 Structural model prediction and quality assessment of Nsxyn1-Nsxyn3 proteins of Neostagonosporella sichuanensisThe number and locations of alpha helices and extended strands were similar between Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, and Nsxyn3 proteins according to the analysis of their secondary structures (Figures 3A–C) and tertiary structures (Figures 3D–F), leading us to hypothesize that all three proteins have similar functions. The tertiary structure quality of the three xylanase proteins was assessed using the SAVES pipeline and Qmean. The overall quality factor of the tertiary structure of Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, and Nsxyn3 was 90.45, 89.11, and 88.89, respectively, as determined by the ERRAT program and Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn3 passed the quality test of the Verify3D program, in contrast to Nsxyn2 where less than 80% (77.97%) of the residues had an averaged 3D-1D score > = 0.1. Nevertheless, the Ramachandran plots generated by PROCHECK showed that over 90% of the amino acid residues of all three proteins were in acceptable regions (Figures 3G–I). On the other hand, the Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, and Nsxyn3 models evaluated by Qmean had Z-scores of-1.27, −1.49, and-1.40, respectively (Figures 3J–L). The SAVES pipeline and the Qmean evaluation results revealed that the tertiary structures of all three protein models predicted by the SWISS-MODEL using the Alphafold v2 method were consistently of good quality and suitable for further experimental study.

Figure 3. Structural analysis and model quality assessment of Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2 and Nsxyn3. (A–C) Secondary structures. The red helices, blue arrows, and black lines indicate alpha helices, extended strands, and random coils. (D–F) 3D structures with “confidence (gradient)” color schemes of Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, and Nsxyn3 were constructed from AlphaFold DB models of 4ZRR9_LEPMJ and W6YRM9_COCMI, respectively. The bluer the models are, the higher the confidence level, while the redder the models are, the lower the confidence level. The coverage and sequence identity of Nsxyn1 (D) were 100 and 82.35%, respectively. The coverage and sequence identity of Nsxyn2 (E) were 100 and 87.22%, respectively. The coverage and sequence identity of Nsxyn3 (F) were 99 and 84.19%, respectively. (G–I) Ramachandran plots of the protein conformations generated by PROCHECK. There are 88.6% core region, 10.3% allow region, 0.5% general allow region, and 0.5% disall region of all amino acid residues of Nsxyn1 (G), respectively, while 88.0% core region, 10.4% allow region, 1.0% general allow region, and 0.5% disall region of all amino acid residues of Nsxyn2 (H). In comparison, 90.7% core region, 8.8% allow region, 0.5% general allow region, and 0.0% disall region of the amino acid residues of Nsxyn3 (I). (J–L) Comparison with the non-redundant set of PDB structures using QMEAN.

3.3 Cloning two candidate xylanases from Neostagonosporella sichuanensisTwo candidate xylanase genes (Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2) were cloned from the cDNA of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001 (Supplementary Figure S1); however, Nsxyn3 was not obtained despite numerous attempts. The sequences of two genes obtained by cloning, Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2, were identical to the sequences from the genome annotation of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis SICAUCC 16–0001, reflecting the accuracy of the genome assembly and annotation results. The functions of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 genes were then further investigated.

3.4 Optimization of expression conditions and purification of Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, Nsxyn1SM113–205, and Nsxyn2SM121–212 recombinant proteinsRecombinant plasmids pET-32a-Nsxyn1 and pET-32a-Nsxyn2 were successfully constructed and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells (Supplementary Figure S2). Expression parameters, including IPTG concentration, induction duration, and temperature, were carefully optimized to improve Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 protein yield and enhance protein solubility. The findings indicated that IPTG concentration did not impact Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 protein expression, so the lowest IPTG concentration of this experiment, 0.2 mM, was chosen to continue optimizing other expression conditions (Supplementary Figures S3A,B). Similarly, the expression of Nsxyn1 was not affected by the duration of induction, so 2 h was optimal (Supplementary Figure S3C). Conversely, 5 h was chosen for pET-Nsxyn2 induction due to the significantly increased amount of induced protein compared to the previous hours (Supplementary Figure S3D). The expression of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins was highest at 30°C (Supplementary Figures S3E,F). The optimal screening conditions induced the expression of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins before purification.

To determine whether the two Glu sites in Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins are essential for the enzyme activity, we conducted site-directed mutagenesis genes, Nsxyn1SM113–205 and Nsxyn2SM121–212. Subsequently, they were transferred to E. coli BL21 (DE3) for overexpression using the previously optimized conditions.

Solubility detection experiments showed that Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, Nsxyn1SM113–205, and Nsxyn2SM121–212 were present as soluble proteins (Supplementary Figures S3G,H). The Nsxyn1, Nsxyn2, Nsxyn1SM113–205, and Nsxyn2SM121–212 proteins were purified before detection of enzyme activity.

The Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 recombinant proteins have xylanase activity and can induce the necrosis phenotype of Nicotiana benthamiana independently of xylanase activity.

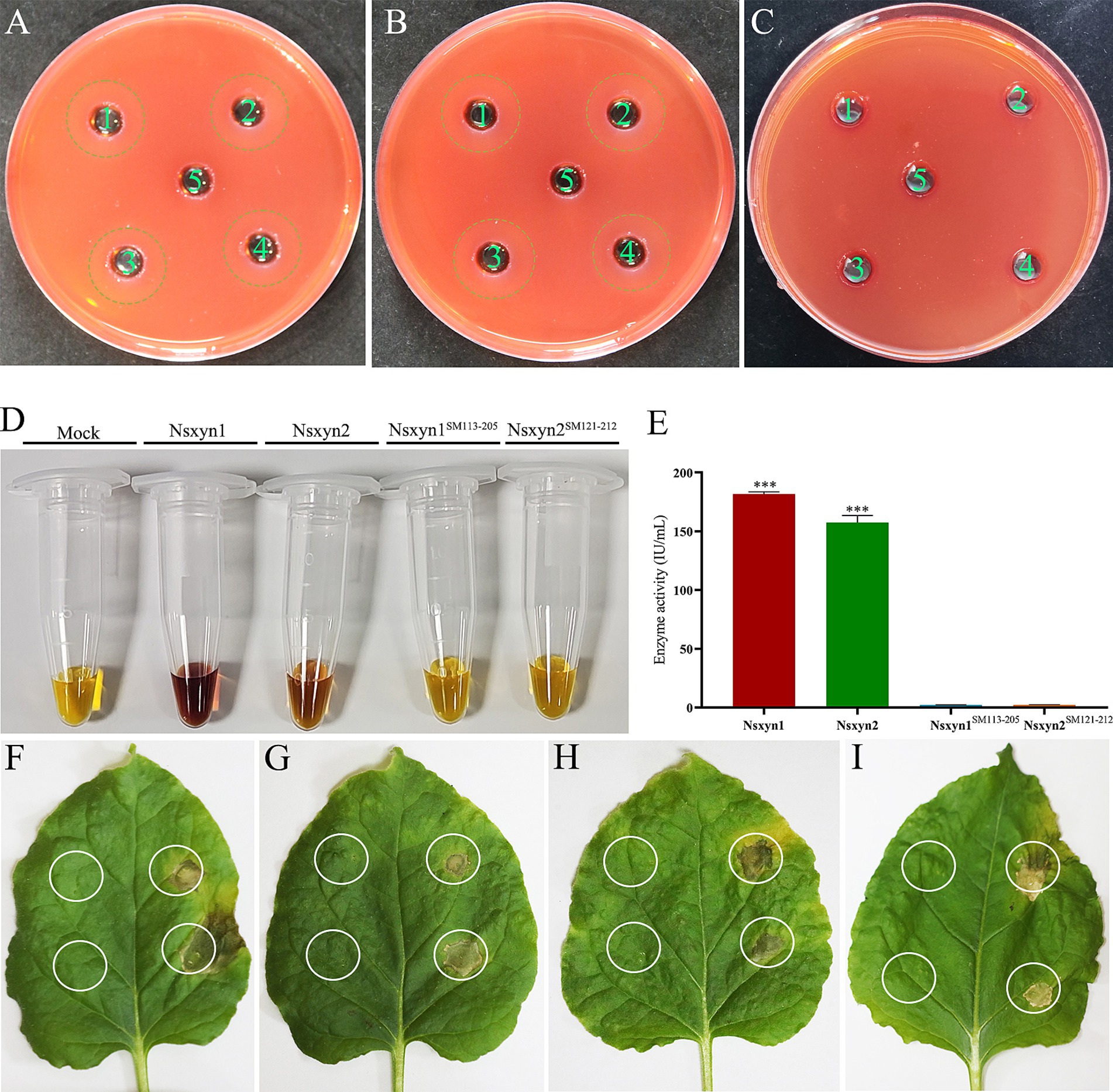

The purified Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins exhibited the ability to hydrolyze xylan to form hydrolytic rings when they were added to the small holes of the medium with xylan as the sole carbon source (Figures 4A,B). On the other hand, Nsxyn1SM113–205 and Nsxyn2SM121–212 lost the ability to degrade xylan (Figure 4C). The above findings align with the quantitative enzyme activity analysis of the purified protein using xylan as substrate (Figures 4D,E).

Figure 4. Qualitative and quantitative determination of the enzyme activity of purified recombinant Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins. Determination of the ability of purified Nsxyn1 (A) and Nsxyn2 (B) proteins to degrade xylan, respectively. 1–4: Recombinant Nsxyn1/Nsxyn2 protein. 5: Control eluent. The hydrolysis circle reflects the ability of Nsxyn1/Nsxyn2 to degrade xylan, and the larger the hydrolysis circle, the greater the ability of the recombinant Nsxyn1/Nsxyn2 protein to degrade xylan. (C) Determination of the xylanase activity of purified Nsxyn1SM113–205 and Nsxyn2SM121–212 proteins to degrade xylan. 1–2: Nsxyn1SM113–205 recombinant protein. 3–4: Nsxyn2SM121–212 recombinant protein. 5: Eluent as control. (D,E) Determination of xylanase activity of Nsxyn1/Nsxyn2 proteins and two site-directed mutants. Xylan was used as the only carbon source for induction in each case. Error bars indicate the standard errors (SE) of the mean. Asterisks *** indicates statistical significance at p < 0.001 based on unpaired Student’s t-tests. Nsxyn1 (F), Nsxyn2 (G), Nsxyn1SM113–205(H), and Nsxyn2SM121–212(I) inducing cell necrosis in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The white ring on the left side of the leaf indicates the blank control for the eluent, while the white circle on the right indicates the location of the purified proteins.

Injection of purified Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves resulted in necrosis approximately 5 days after treatment (Figures 4F,G). To determine whether this necrosis was related to the enzymatic activity of these proteins, site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate catalytic site mutants (Nsxyn1SM113–205 and Nsxyn2SM121–212) in both proteins. Despite the loss of enzymatic activity, the mutant proteins still induced necrosis in N. benthamiana leaves, comparable to the unmutated proteins (Figures 4H,I). These findings suggested that the necrosis-inducing activity of these xylanase proteins is independent of their enzymatic function.

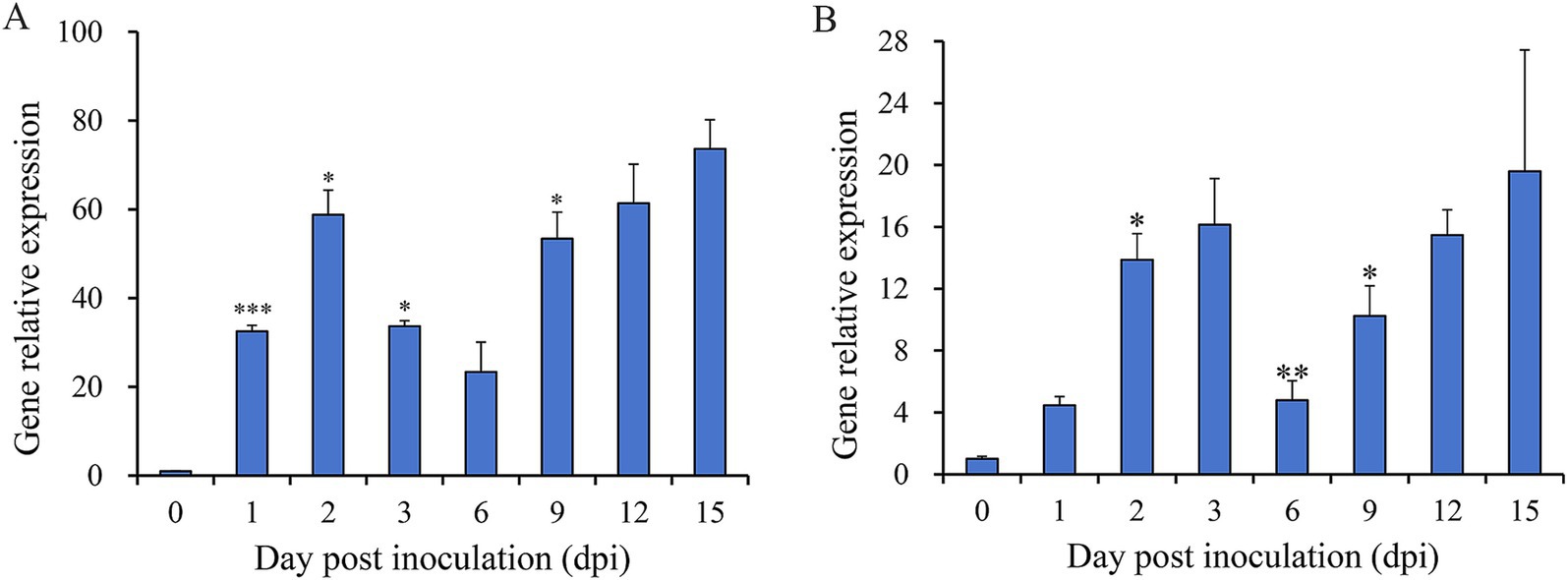

3.5 Quantitative analysis of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 expressionTo assess the involvement of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 in the infection process of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis, their expression levels at different periods of infection with fishscale bamboo were determined using qRT-PCR (Figure 5). Under non-inductive conditions, the expression levels of both genes were at their lowest, normalized to 1. Expression analysis revealed significant up-regulation of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 during the infection process, with Nsxyn1 showing a particularly strong increase, reaching an 80-fold up-regulation at 15 days post-inoculation. These results suggest that Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 are strongly induced during infection.

Figure 5. Relative expression levels of Nsxyn1 (A) and Nsxyn2 (B) at different infection times of Neostagonosporella sichuanensis. Error bars represent standard errors (SE). Asterisks *, **, and *** on the SE line are statistically significant differences at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively, as determined by unpaired Student’s t-tests.

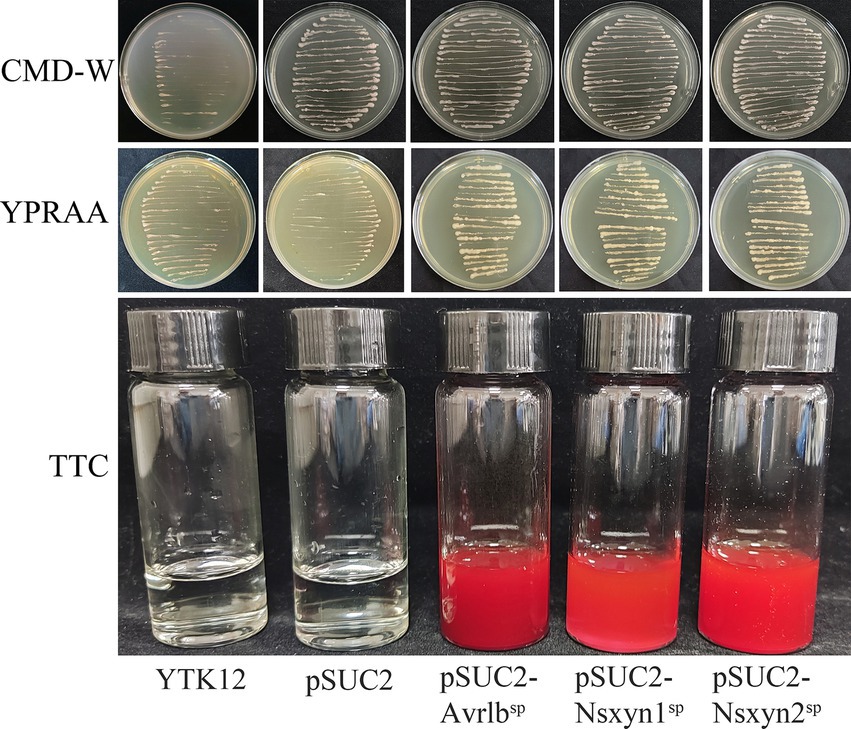

3.6 Signal peptides of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins have secretory functionsThe Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 genes were inserted into the pSUC2 vector and subsequently transformed into the YTK12 yeast strain. Both transformants grew on CMD-W and YPRAA selective media, indicating successful gene expression (Figure 6). Similarly, the positive control strain harboring the pSUC2-Avr1bSP construct also exhibited normal growth, whereas the negative control showed no growth, confirming the validity of the experimental system. Further TTC staining analysis revealed that YTK12 strains expressing Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 produced a red precipitate. These results strongly suggest that the proteins encoded by these genes contain functional signal peptides that facilitate secretion.

Figure 6. Functional assessment of the Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 signal peptides. YTK12 strains carrying pSUC2-Nsxyn1SP, pSUC2-Nsxyn2SP together with pSUC2-Avr1bSP (positive control) are capable of growth on CMD-W medium and YPRAA media, whereas the YTK12 strain devoid of vector and possessing pSUC2 empty vector (negative controls) do not. Additionally, the YTK12 strains containing pSUC2-Nsxyn1SP, pSUC2-Nsxyn2SP, and the positive control change the color of the reaction mixture from colorless to bright and dark red in the TTC assay, whereas the negative controls show no color change.

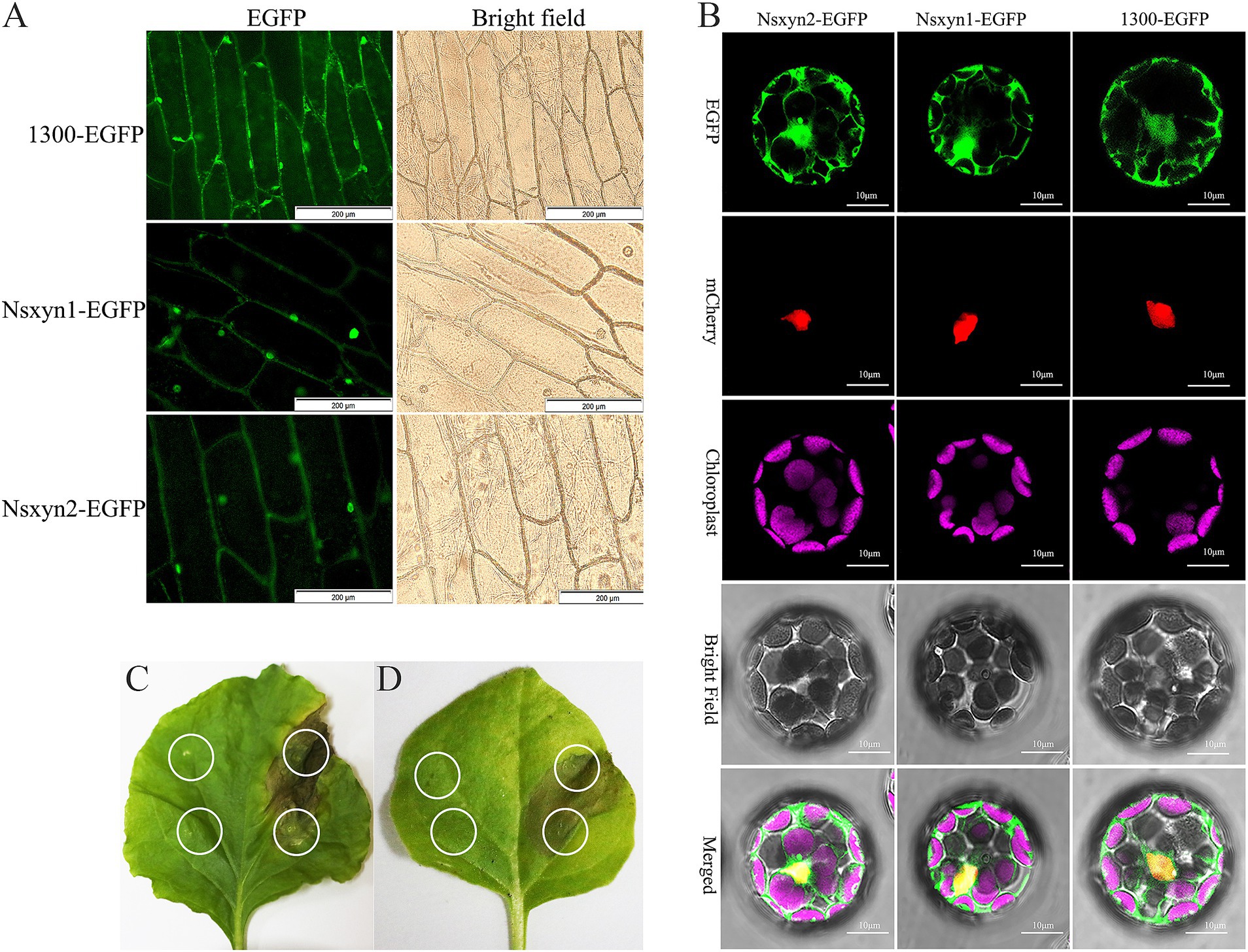

3.7 Subcellular localization of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins and their role in inducing necrosis in Nicotiana benthamianaThe plasmid maps and electrophoretic analysis during vector construction are presented in Supplementary Figure S4. All fluorescence signals were effectively recorded using confocal laser scanning microscopy in the onion epidermal cells (Figure 7A) and Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts (Figure 7B) expressing the Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2. Results from the transient expression system showed that onion epidermal cells with empty PCAMBIAsuper1300-GFP carriers emitted green fluorescence throughout the cell structure. However, EGFP green fluorescence was mainly distributed in the nuclear onion cells with pCAMBIAsuper1300-Nsxyn1-EGFP or pCAMBIAsuper1300-Nsxyn2-EGFP overexpression carriers. Furthermore, when examined in A. thaliana protoplasts, the Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 xylanases displayed a dual localization pattern in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Together, Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins were localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Figure 7. Subcellular localization of the Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins is examined in onion epidermal cells (A) and Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts (B). The pCAMBIA1300-EGFP vector is used as a control. In Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts, red fluorescence indicates nuclear markers, while purple fluorescence is due to chloroplast autofluorescence, and the green fluorescence emitted by the pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector is visible. Membrane and nuclear markers exhibit red fluorescence. Transient expression of Nsxyn1 (C) and Nsxyn2 (D) are both observed to induce necrosis in N. benthamiana leaves. The white ring on the left side of the leaf denotes the negative control, where only EGFP-expressing Agrobacterium suspensions are infiltrated. The white circles on the right indicate the regions infiltrated with Nsxyn1-EGFP (C) and Nsxyn2-EGFP (D) Agrobacterium suspensions, respectively.

Transient expression of Nsxyn1-EGFP and Nsxyn2-EGFP in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves resulted in localized cell necrosis, as evidenced by visible necrotic lesions at the infiltration sites (Figures 7C,D). In contrast, the EGFP control did not induce any signs of necrosis, and the leaves remained healthy. This suggested that Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 possessed necrosis-inducing activity in plant cells, independent of the fluorescent tag.

3.8 Obtaining gene knockout and knockout complementationDeletion and complementation strains for both genes were generated to investigate the role of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 in cell wall degradation (Supplementary Figures S5, S6). It was observed that Neostagonosporella sichuanensis exhibited minimal growth on plates containing either 90 μg/mL hygromycin B or 200 μg/mL G418 (Supplementary Figure S7), leading to the selection of these concentrations for transformant screening. The deletion strains of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 were verified by PCR analysis (Supplementary Table S1), and positive transformants were chosen for further study (Supplementary Figures S8, S9).

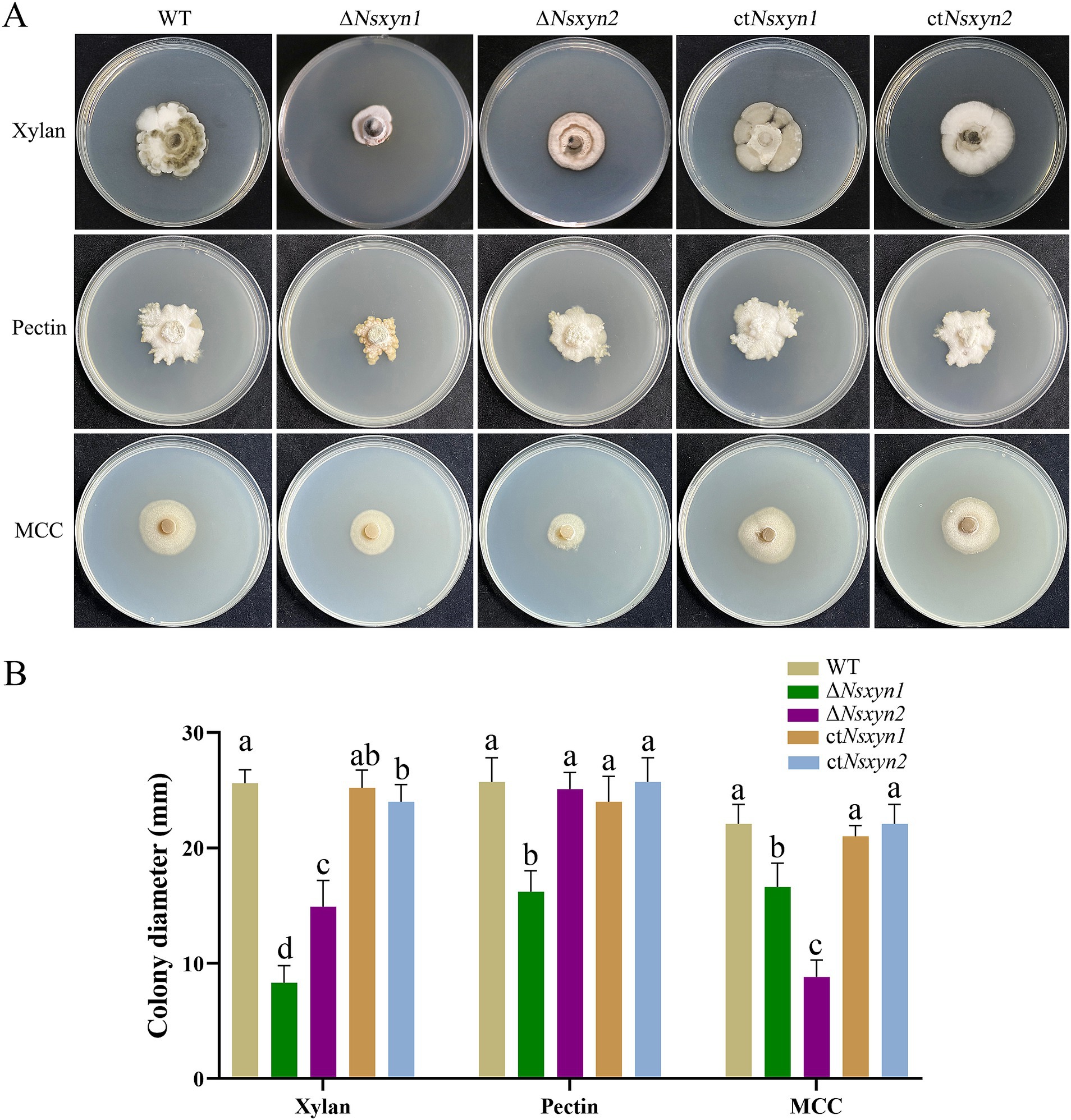

3.9 Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 proteins display cell wall-degradation activityThe capacity of the deletion mutants (ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2) and the complementation strains (ctNsxyn1 and ctNsxyn2) to degrade cell wall components was evaluated on the C’zapek media that was devoid of carbon sources but supplied with xylan, cellulose, or pectin. On the C’zapek medium with xylan as the sole carbon source, colony diameters of ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2 mutants were significantly smaller than those of the wild type (Figure 8). Additionally, the colony diameter of the ΔNsxyn1 mutants was unexpectedly decreased on C’zapek media with cellulose or pectin, while the ΔNsxyn2 mutants showed a similar reduction only when grown on C’zapek medium with pectin. The complementation strains, ctNsxyn1, and ctNsxyn2, completely restored cellulose and pectin degradation capacity and partially restored the potential for xylan degradation.

Figure 8. Growth observations of the Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 knockout mutants and complement strains on basic C’zapek medium, utilizing xylan, pectin, or microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as the sole carbon source. (A) Photographs of the growth phenotypes were taken after incubation at 25°C for 30 days. (B) Comparison of colony diameters. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. Distinct lowercase letters indicate significant differences in colony diameter among the various strains on the same type of culture media at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA.

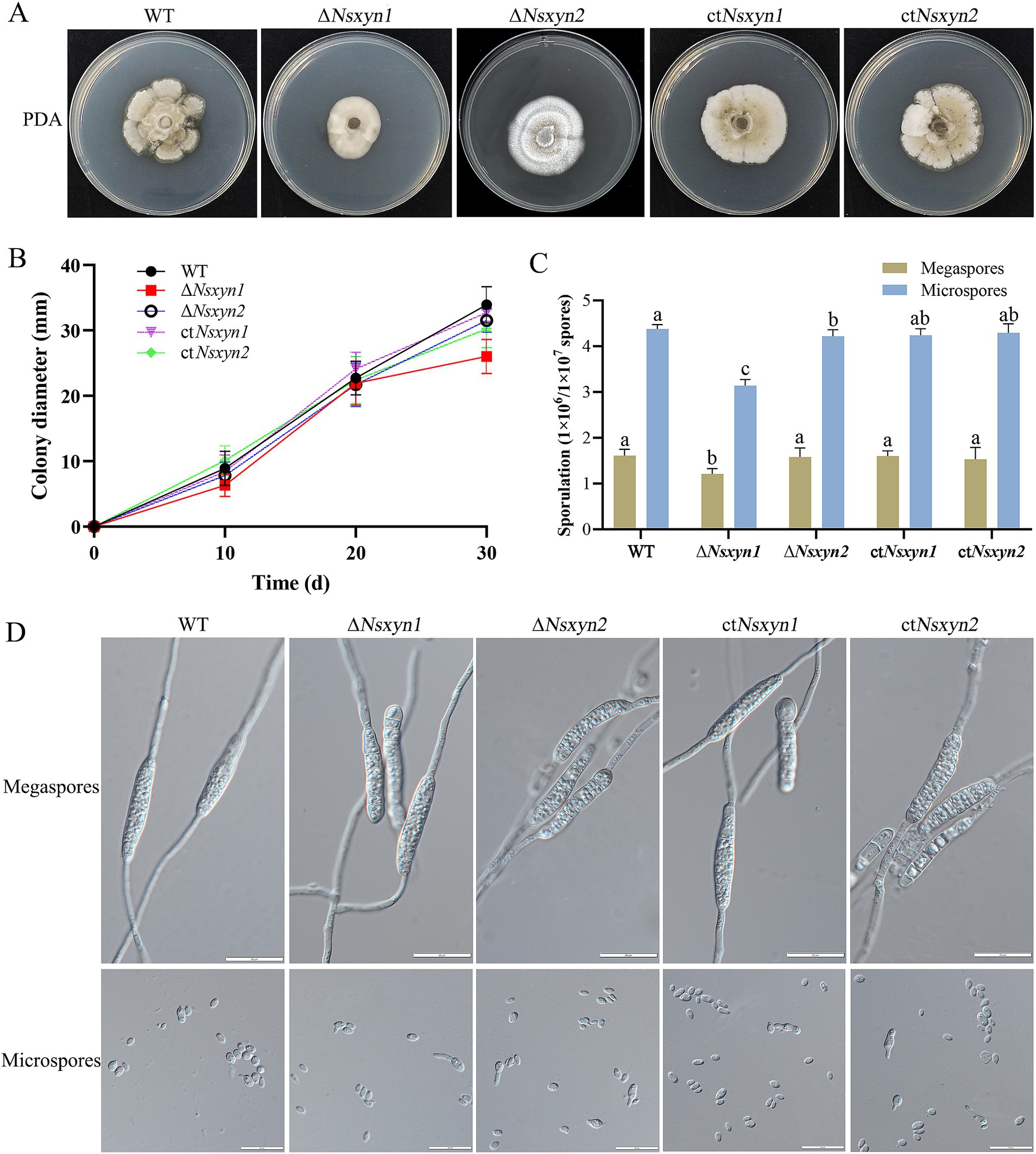

3.10 Analysis of phenotypic, sporulation, and spore germination of transformationTo examine the impact of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 gene deletion on the growth of Neostagonosporella sichuanesis, mycelial plugs of wild type, ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2 mutants, and the ctNsxyn1 and ctNsxyn2 complement strains were inoculated on PDA medium under light/dark (12 h/12 h) conditions at 25°C for 30 days. A significant decrease in colony diameter and spore production was observed in the ΔNsxyn1 mutant relative to the wild type (Figures 9A–C). In contrast, no strong negative effect on the growth rate was observed in the ΔNsxyn2 mutant (Figures 9A,B). However, it was found that the colony morphology of the ΔNsxyn2 mutant changed, shifting from a smooth surface to a cotton-like appearance, with a corresponding reduction in microconidia production compared to the wild type (Figures 9A,C). Spore production only statistically partially recovered, and the growth rate was restored after complementation. Additionally, the conidial morphology of all transformant strains did not differ significantly from that of the wild type, and all strains were able to germinate normally (Figure 9D).

Figure 9. Colony phenotypes (A), mycelial growth rates (B), conidial sporulation statistics (C), and germination morphology of megaspores and microspores (D) from different strains (wild-type strain, Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 deletion strains, and their corresponding complementation strains) grown under light/dark (12 h/12 h) conditions at 25°C for 30 days. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences in megaspore/microspore sporulation among the various strains at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA. The unit for counting megaspores is 1 × 106 spores, while the unit for counting microspores is 1 × 107 spores.

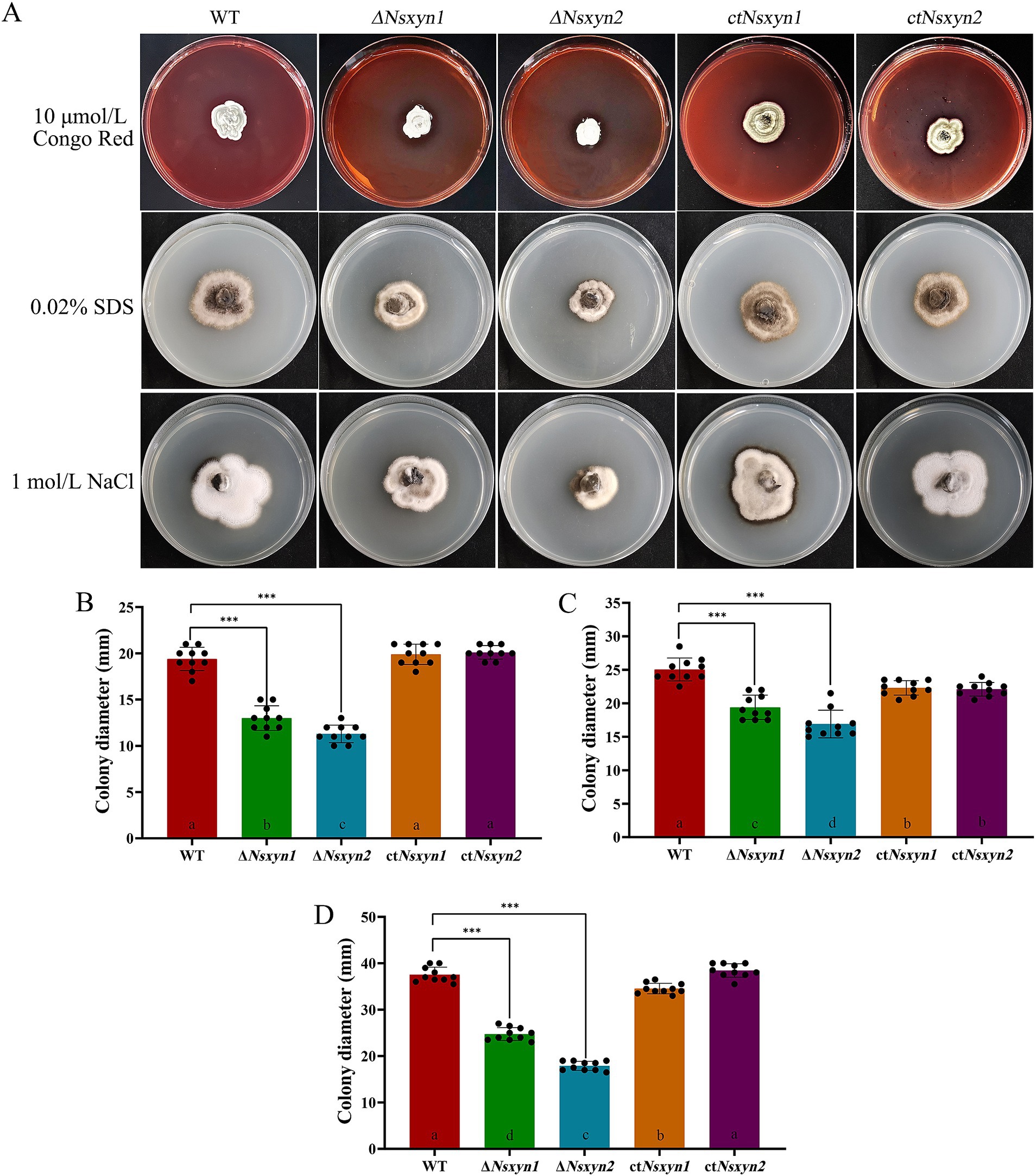

3.11 Stress response of transformantsThe integrity of the fungal cell wall is crucial for successful host cell infection, as it maintains the shape of the fungal cell and regulates interactions with the external environment (Cabib et al., 2001). Continuous cell wall remodeling is required for proper fungal growth and development (Bowman and Free, 2006). We assessed the effects of cell wall-disrupting agents on the growth of the ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2 mutant strains (Figure 10). Colony size measurements were employed to quantify the growth inhibition rate, revealing that the ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2 strains exhibited significant sensitivity to cell wall stressors, including Congo red, SDS, and NaCl. Notably, the ΔNsxyn2 strain displayed greater sensitivity than the ΔNsxyn1 strain.

Figure 10. Sensitivity of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 mutants to cell wall stress-inducing agents. Colony morphology (A) and colony diameter measurements (B–D) of the wild-type strain (WT), Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 deletion mutants (ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2), and their corresponding complement strains (ctNsxyn1 and ctNsxyn2) were assessed after culturing on PDA media supplemented with various cell wall perturbing agents for 30 days. (B) 10 μmol/L Congo Red (CR); (C) 0.02% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS); (D) 1 mol/L NaCl. Colony diameters were averaged from ten technical replicates, and error bars represent standard errors. Asterisks (***) indicate a significant difference (p < 0.001) based on unpaired Student’s t-tests. Different letters on the bar charts denote statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA).

3.12 Pathogenicity test of transformantsPathogenicity assays were conducted to determine the roles of Nsxyn1 and Nsxyn2 in rhombic-spot disease on living fishscale bamboo culms. The wild-type strain caused typical necrotic symptoms. In contrast, while the ΔNsxyn1 and ΔNsxyn2 mutants displayed similar symptoms, their virulence was significantly reduced (Figure 11). Complementation strains ctNsxyn

留言 (0)