Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract. It causes a range of conditions in men and women, including precancerous lesions that may progress to cancer1. HPV16 and HPV18 together are responsible globally for 71 per cent of cases of cervical cancer. Almost all cervical cancer cases (99%) are linked to infection with high-risk HPV. In 2020, an estimated 6,04,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer worldwide, and about 56.6 per cent of the women died from the disease. It is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. India accounts for the largest proportion of the global load of cancer cervix, which is the second most common cancer in women in India2. Unlike many other cancers, cervical cancer occurs early and strikes at the reproductive period of a woman’s life.

The World Health Assembly adopted the ‘Global Strategy for Cervical Cancer Elimination’ in August 20203. To reach incidence rate less than 4 per 1,00,000 women to eliminate cervical cancer, 90-70-90 targets need to be reached by 2030: fully vaccinating 90 per cent of girls with the HPV vaccine by 15 yr of age; screening 70 per cent of women using a high-performance test by the age of 35, and again by the age of 45; and treating or managing 90 per cent of women with pre-cancer or invasive cancer, respectively4.

In settings with high cervical cancer burden and poor access to screening and treatment, HPV vaccine introduction offers the best, and sometimes, the only opportunity to prevent disease. In India, Sikkim introduced the HPV vaccine in the entire State in 2018 after detailed pre-roll-out preparation5.The indigenously developed quadrivalent HPV vaccine is being considered for introduction in the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) as a two-dose regimen for girls between 9–14 yr of age. Immunization of boys is recommended once 80 per cent routine immunization coverage is achieved in girls6. Vaccine hesitancy is among the top ten global threats according to the World Health Organisation (WHO)7. Studies conducted globally have shown high vaccine hesitancy among parents towards HPV vaccine. Parental vaccine hesitancy8-11 is strongly associated with adolescents not receiving HPV vaccination. Educational interventions11-16 have been proven effective in reducing hesitancy towards HPV vaccine.

The uptake of the HPV vaccine, which is about to be introduced in UIP, can be predicted by assessing its acceptance. Hence, this study was conducted to assess the acceptance of the HPV vaccine among parents of adolescent girls and to evaluate the effect of a one-on-one health education programme on the same. As per the authors’ knowledge, no such study has yet been conducted in Manipur.

Material & MethodsA quasi-experimental study was conducted from February to May 2023 among parents of adolescent girls aged 9-14 yr in the field practice area of the Rural Health Training Centre, Bishnupur. Manipur has 2,95,130 adolescent females as per United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Report 201117. The district of Bishnupur has 67 per cent coverage of all essential vaccinations among children aged 12-23 months (NFHS-5)18. The participants residing in the district for at least one year and those using WhatsApp mobile application were included, and those households in which, even after two visits, no one could be contacted were excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Board. The trial was prospectively registered (CTRI/2023/02/049771) in the Clinical Trial Registry of India.

Sample size and samplingUsing the sample size formula for paired proportions, taking baseline HPV vaccine acceptance as 71 per cent from a study conducted by Madhivanan et al16, type I error 0.05 and 80 per cent power, 42 participants were needed to detect a 20 per cent increase in vaccine acceptance. These assumptions were followed because, while conducting this study, there were no similar studies examining the impact of health education on HPV vaccine acceptance. Hence, an assumption of 20 per cent improvement in acceptance was made after discussion with the subject experts. With a 20 per cent drop-out rate, the final sample size needed was 51. Households with parents of adolescent girls were conveniently selected from the field practice area of the Rural Health Training Center, Bishnupur, and one parent was included from each household. The researchers posted there for rural postings went by foot during the daytime to identify eligible participants. Hence, it was convenient for them to include the nearby families based on distance and time, subject to the availability and willingness of parents to participate. When both parents were available, their convenience for the interview was asked and accordingly a participant was selected. Privacy was maintained during data collection by conducting one-on-one health educational intervention in a separate room where only the investigator and participant were present. A unique code number was assigned. Data were kept secure, and only the investigators had access. Identifiers like name and address were not taken, and data was presented cumulatively.

Study toolA self-designed and pre-tested structured questionnaire, including sections on background characteristics, HPV vaccine acceptance, and beliefs, was employed. Nine questions were asked on background characteristics. The section on HPV vaccine acceptance consisted of two questions. The first question assessed the participant’s acceptance of their daughter receiving the HPV vaccine, and the responses were: ‘Definitely not, probably not, probably yes, definitely yes,’ and the second question assessed the social norms influencing the participant’s acceptance of the HPV vaccine. The section on attitude and beliefs consisted of 12 questions covering four constructs of the health belief model (perceived severity: 2, susceptibility: 2, barriers: 4, and benefits: 4), and the questions were scored from 1 to 5 on a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, not sure, agree, strongly agree). Maximum and minimum attainable scores in severity and susceptibility domains were 2 and 10, whereas barriers and benefits were 4 and 20, respectively. The modified BG Prasad scale19 (2022) was used to determine socioeconomic class.

The video prepared by the Danish medicine agency in partnership with the WHO regional office for Europe and made available for use in other countries was given voice-over in the local language by the research team. The researchers prepared the pamphlet and Information Education Communication (IEC) images used for educational intervention, and two subject experts from the institution validated the content of all intervention materials.

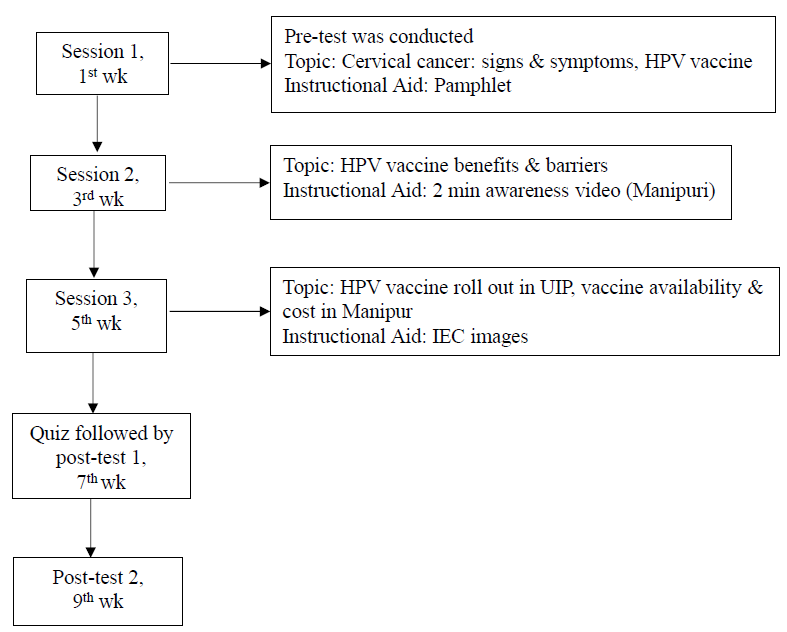

InterventionThe intervention comprised three sessions followed by post-tests 1 and 2 with a 2-wk interval between each, as shown in figure. During the first session, researchers collected baseline data. They administered a pretest, followed by the first educational session- a pamphlet-aided face-to-face discussion on the signs and symptoms of cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine. The pamphlet (Supplementary Fig. 1) was in the local language and English. Two wk later, for the second session, a two-minute awareness video on HPV vaccine advantages and hurdles was distributed over WhatsApp ( https://drive.google.com/file/d/1jiGVXEfFzg4SNiV6bpcbK5N7aR7NgD7C/view?usp=drive_link ). After two wk, for the third session, IEC images (Supplementary Fig. 2) on HPV vaccination rollout in UIP, vaccination availability, and pricing in Manipur were sent via WhatsApp mobile application. Researchers contacted the participants by phone after sending the interventions to confirm if they saw and understood the materials. A quiz followed by post-test 1 was done face-to-face at participants’ houses two wk later. Post-test 2 was conducted two wk after post-test 1.

Export to PPT

Operational definitionThose participants who responded ‘definitely yes’ to getting their daughters vaccinated with the HPV vaccine were considered ‘vaccine acceptant’, and those who answered ‘probably yes, probably not or definitely not’ were considered ‘vaccine-hesitant’. A higher mean score in perceived severity, susceptibility, and benefits and a lower mean score in the perceived barriers domain during follow-up was considered a favourable change in attitude towards vaccine acceptance.

Data collectionA house-to-house visit was done to identify households with adolescent girls. One parent from each household was selected. The purpose of the study was explained to the study participants, and written informed consent was obtained. Data were collected at baseline, seventh wk (post-test 1) and ninth wk (post-test 2) by face-to-face interview and recorded using Google forms. Acceptance of the HPV vaccine was evaluated before and after intervention.

Statistical analysisData collected were checked for completeness and consistency and were then exported and analyzed in IBM SPSS 26 for Windows (IBM Corp. Chicago, U.S.). Descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentages were used. Chi square test was used to test the significance of difference between background characteristics and HPV vaccine acceptance. Change in HPV vaccine acceptance across different time points was analyzed using Cochran’s Q test. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze change in mean score of ‘attitudes’ across various time points. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsThere was no loss to follow up during the study, and 70 respondents completed both the pretest and post-tests. All background characteristics are shown in Table I. The median age of the participants was 38 yr (IQR: 34-44), with the majority 54 (77.1%) of the respondents being mothers. Most participants, i.e., 41 (58.6%), belonged to the Hindu religion, and 39 (59.7%) were educated up to secondary school level or below. The majority, 40 (57.1%), were unemployed, and 26 (37.2%) economically belonged to the upper-middle or upper-class families as per the modified BG Prasad scale10. Most participants, 65 (92.9%), had their children with UIP vaccination status as complete. Among the participants 15 (21.5%) had experienced cancer themselves or with their family members or relatives and only six (8.6%) had awareness about HPV vaccine.

Table I. Distribution of participants according to their background characteristics (n=70)

Background characteristics Total participants, n (%) Age (in completed yr) 25-33 17 (24.3) 34-38 19 (27.1) 39-44 18 (25.7) ≥45 16 (22.9) Respondent Father 16 (22.9) Mother 54 (77.1) Religion Hinduism 41 (58.6) Sanamahism 15 (21.4) ^Others 14 (20) Educational qualification No formal education 7 (10) Primary or secondary school 39 (55.7) High school & above 24 (34.3) Occupation Unemployed 40 (57.1) Employed 30 (42.9) Socio-economic status Lower & lower middle-class 19 (27.1) Middle class 25 (35.7) Upper-middle & upper-class 26 (37.2) UIP vaccination status Incomplete/Don’t know 5 (7.1) Complete 65 (92.9) Experience of cancer-self/family members/relatives Yes 15 (21.5) No 55 (78.5) Awareness of the HPV vaccine Yes 6 (8.6) No 64 (91.4)The baseline acceptance for HPV vaccine among parents of adolescent girls was 61.5 per cent. During pretest, when asked about vaccinating their daughter with HPV vaccine, 43 (61.5%) responded ‘definitely yes’, 26 (37.1%) said ‘probably yes’ and 1 (1.4%) said ‘probably not’.

Table II shows that HPV vaccine acceptance improved significantly from 61.5 to 81.4 to 88.6 per cent (P=0.001). There was a significant increase in mean scores of ‘perceived susceptibility’ (P<0.001) and ‘perceived benefits’ (P<0.001) across different time points, but no statistically significant change in scores of ‘perceived severity’ (P=0.051) and ‘perceived barriers’ (0.367).

Table II. Effect of intervention on HPV vaccine acceptance and attitude towards HPV vaccine at different time points (n=70)

HPV vaccine acceptance Pre-test Post-test 1 Post-test 2 Acceptant*, n (%) 43 (61.5) 57 (81.4) 62 (88.6) Attitude: Health belief model domains (mean±SD) Perceived severity 8.7±1.17 9.06±1.42 9.29±1.07 Perceived susceptibility* 7.02±1.67 8.19±1.56 8.09±1.69 Perceived barriers 14.05±2.83 13.36±2.97 13.71±2.56 Perceived benefits* 16.75±1.61 17.91±2.11 18.09±2.25Pairwise comparisons (Table III) showed significant improvement in HPV vaccine acceptance at post-test 1 (P=0.022) and 2 (P=0.001) compared to pre-test, respectively but no significant change between post-tests 1 and 2. There was a significant increase in ‘perceived severity’ (P=0.045) at post-test 2 compared to the pre-test. ‘Perceived susceptibility’ and ‘perceived benefits’ increased significantly at post-tests 1 and 2 compared to pretest, but there was no significant change in post-tests 2 and 1 scores. There was no significant association between socio-demographic characteristics and vaccine acceptance in both pre-test and post-test (Supplementary Table I). Distribution of participants responses for each statement based on their attitude and belief of HPV vaccine is mentioned in Supplementary Table II.

Table III. Pairwise comparison of HPV vaccine acceptance and their attitude towards HPV vaccine across time points (n=70)

Time points Change (B-A) A B HPV vaccine acceptance (% change)* Pre-test Post-test 1 20§ Pre-test Post-test 2 27.2§§ Post-test 1 Post-test 2 7.2 Attitude towards HPV vaccine (mean change)† Perceived severity Pre-test Post-test 1 0.271 Pre-test Post-test 2 0.5§ Post-test 1 Post-test 2 0.229 Perceived susceptibility Pre-test Post-test 1 1.157§ Pre-test Post-test 2 1.057§§ Post-test 1 Post-test 2 0.1 Perceived barriers Pre-test Post-test 1 0.7 Pre-test Post-test 2 0.343 Post-test 1 Post-test 2 3.57 Perceived benefits Pre-test Post-test 1 1.157§§ Pre-test Post-test 2 1.329§§ Post-test 1 Post-test 2 0.071 DiscussionThis community-based quasi-experimental study showed the effectiveness of one-on-one health education on parental HPV vaccine acceptance. Only two participants had children with incomplete UIP vaccination status, the reason for which was the COVID-19 pandemic. The high vaccination coverage (>90%) in the sample compared to that as reported in NFHS 5 (67%) for Bishnupur could be attributed to many factors, such as our participants being selected through a convenience sampling approach, self-reported responses, or in general, increased vaccine acceptance over time.

Studies have shown a lack of awareness of HPV infection and cervical cancer as one of the major reasons for poor HPV vaccine uptake20,21. In this study, only 8.6 per cent of participants were aware of the vaccine, which could protect against HPV infection and cervical cancer, compared to 22.3 per cent knowledge about the HPV vaccine in a study conducted by Musa et al22 in Nigeria. The difference may be because, in India, campaigns for the HPV vaccine have not yet gained momentum compared to the other routine vaccinations23,24. Studies have shown that improving knowledge of HPV and cervical cancer increases acceptance of the HPV vaccine25,26. Those aware of the HPV vaccine had a significant positive association with vaccine acceptance (P=0.010) during the pretest in this study. Educational interventions such as pamphlets and videos have been shown to improve awareness and acceptance. Studies done in Pennsylvania and Chennai demonstrated that video served better than pamphlets or lectures in improving acceptance12,13.

Previous experiences from Sikkim27 showed that mandatory school enrolment and collaboration between the health and education sectors were critical factors for the high coverage of the HPV vaccine. Even though vaccine rollout in other States of India will be through schools, improving acceptance by approaching parents in the community through one-on-one health education by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and healthcare workers will be crucial considering the current era of misinformation and disinformation.

In our study, as captured by pretest, the baseline acceptance of the HPV vaccine among parents of adolescent girls was 61.4 per cent even though awareness was 8.6 per cent. This could have been due to the brief introduction to the HPV vaccine given by researchers after completing the first section of the questionnaire, which could be attributed to factors like trust in healthcare providers and general vaccine acceptance. In post-tests 1 and 2, acceptance increased to 81.4 per cent and 88.6 per cent, respectively, which showed that the health education programme effectively improved parental acceptance of the HPV vaccine. Studies have demonstrated that educational interventions on HPV-related illnesses effectively increase knowledge and vaccine acceptability in America, Malaysia, Korea, Turkey, and Hong Kong12,14,15,28,29.

There was a significant improvement in attitude in perceived benefits and susceptibility domains following the intervention. This is consistent with previous studies14,30,31, which reported improvement in attitude after providing adequate information through educational intervention. The proportion of people who strongly agreed that HPV infection was harmful increased from 44.3 to 67.2 per cent, and those who strongly agreed that cervical cancer was a serious disease increased from 51.5 to 70 per cent. Similarly, regarding susceptibility, the proportion of those who strongly agreed that their daughter might one day be at risk of HPV infection increased from 5.7 to 35.7 per cent post-intervention. Those who strongly disagreed that they were concerned about the side effects of vaccination increased from 8.6 to 17.1 per cent. Concerns about side effects should be addressed appropriately when vaccine rollout happens. The perception of cost as a barrier increased after intervention, which could have resulted from cost aspects being explained in detail during intervention. Cost concerns should be reduced once the HPV vaccine is rolled out through UIP.

As we used multiple modes such as video, discussion, images and pamphlet along with approaching each participant in person, this must have addressed most of the concerns resulting in the significant increase in acceptance. Educational pamphlet developed for this study may be helpful for providers to guide patients in clinical settings and stakeholders in community settings. Similar to the study conducted by Pearl et al13, we didn’t find any significant association between socio-demographic characteristics and vaccine acceptance. This may be due to the selection of participants from a setting with less diverse characteristics.

However, vaccine acceptance attitude may not necessarily convert into vaccinating behaviour. Several factors can influence vaccine acceptance: accessibility, convenience, financial barriers, follow-ups, health literacy, etc. It needs to be assessed later on by follow-up. Similarly, vaccine acceptance cannot be confirmed unless it translates into actual vaccine uptake – a fact that needs long-term follow-up to see how the vaccine coverage peaks once vaccine rollout happens.

Strength and limitationsThis is probably the first study in Manipur on the effect of educational interventions on HPV vaccine acceptance. The educational and one-on-one sessions in local language addressed most of the concerns participants had regarding the HPV vaccine. Selection bias arising from convenience sampling and information bias due to self-reported responses limits the generalizability of our study findings. Hence, further studies using random sampling should be encouraged.

Overall the study found that six out of 10 participants were vaccine acceptors at baseline, while nine out of 10 participants were unaware of the HPV vaccine. Health education intervention was effective at improving vaccine acceptance significantly over time. ‘Perceived susceptibility’ towards disease and ‘perceived benefits’ of vaccine improved significantly as well. Large-scale awareness programmes before the roll-out of HPV vaccination and continuous re-enforcement would have the potential to improve the parents’ perceived benefits of the HPV vaccine, thereby increasing vaccine coverage.

留言 (0)