The transition to motherhood, starting in pregnancy, giving birth, and the 12-month postnatal period are significant life events for women (1, 2), a time defined as the perinatal period (3). This transition to motherhood, a catalyst for significant shifts in a woman’s identity (4), can challenge a woman’s sense of self (5) and encompass shifts in self-concept which negatively impact mental health (6).

Women often have established personal standards that they aspire to adhere to as a mother, which can be referred to as personalised ideals (7). Women can also be exposed to societal myths surrounding motherhood (8) and societal principles conceptualising what constitutes a ‘good mother’ (9, 10), which can contribute to forming a woman’s internalised societal motherhood ideals. One example is the ‘Good Mother’ ideology (10). It is the integration of these personalised and internalised societal ideals and the woman’s actual experiences of being a mother that happens during the formation of the ‘motherhood identity’ (4, 11, 12).

However, an incongruity can occur between the woman’s actual experience and their pre-existing ideals of motherhood (5). Women who persistently experience greater discrepancy between their prior ideals and lived reality are at a greater risk of experiencing emotional difficulties, such as anxiety (13), low self-esteem (13), severe postpartum depression (14, 15), feelings of inadequacy (16), or shame and guilt (7, 17). Perceiving oneself as an ineffective or non-nurturing mother can contribute to difficulties, such as the development of postnatal depression (18). It is not only the comparison of their actual experience to internalised ideals that appears to influence the emotional well-being of the mother, because the process of external comparison with other mothers is also important: higher rates of depression are observed in mothers who negatively compare their actual motherhood experience to that of other mothers (19). Conversely, as mothers who possess positive self-esteem and a healthy self-concept tend to experience higher emotional well-being (20, 21), decreasing the discrepancies between internalised motherhood ideals and a person’s lived reality can play a vital role in achieving a successful transition to motherhood (22).

The perinatal period, especially the first 30 days postpartum, represents one of the highest-risk periods for women in their lives for the development of new and/or recurrence of pre-existing mental health conditions (23–27). Mental health conditions, such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and psychosis, are the most common difficulties to occur in the perinatal period (24, 28). Globally, approximately one in five women will experience a mental health condition in the perinatal period, with disparities observed across low-, middle-, and high-income countries (29). The rates of perinatal mental health conditions in the UK are reflective of the global average, with approximately 20% of British women experiencing such difficulties (30).

In the UK, approximately 4 in 1,000 women with perinatal onset mental health conditions require more intensive psychiatric support accessed through an inpatient admission, ideally to a specialist inpatient Mother and Baby Unit (MBU) (30, 31). MBUs offer joint mother–infant inpatient admissions, facilitating psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial assessment and intervention for the mother while also enriching the mother–infant attachment (30–32). Effective care and treatment of a mother’s mental health during the perinatal period is paramount because untreated perinatal mental health conditions can result in adverse effects for both the mother and her developing child (33, 34). In their systematic review of published psychological guidance for perinatal mental health, O’Brien et al. (35) emphasised the importance of targeting both maternal mental health difficulties and the mother–infant dyad to achieve effective outcomes, a goal made possible through a joint MBU admission.

The benefits of MBUs have been noted. In their systematic review of 23 studies, Gillham and Wittkowski (36) identified that MBU admission improved maternal clinical symptoms, maternal confidence, child development, and the mother–baby relationship, including enhanced infant attachment. The finding of improved maternal outcomes following MBU admission was upheld by a more recent systematic review of 44 studies by Connellan et al. (37) and by the empirical studies of Branjerdporn et al. (38), Stephenson et al. (39), and Wright et al. (40).

MBU co-admission is preferable in supporting maternal mental health conditions during the perinatal period in many ways over mother-only general psychiatric hospital admission (41), and women admitted to an MBU seem to express high levels of care satisfaction (38, 42). The Effectiveness of Services for Mothers with Mental Illness (ESMI) research programme report (43) noted that mother–infant separation resulting from individual maternal hospitalisation can be perceived as traumatic by mothers and detrimental to the mother–infant dyad, ultimately hindering recovery. Indeed, mothers expressed that being with their baby had been an important factor in recovery (41, 44). However, most studies illustrating the benefits of MBU admission for both mother and baby utilised methodological approaches susceptible to social desirability and researcher biases, such as interviews, observational methods, standardised psychometrics, and rating scales (45).

A more appropriate methodology is the repertory grid technique (RGT) (46), an assessment tool derived from Personal Construct Theory (PCT0) (47). PCT postulates that people engage in an ongoing process of utilising an idiosyncratic system of personal constructs to understand and distinguish between elements within themselves and among others in the world, a process termed construing (48). Examples of elements include the actual self, ideal self, and person of trust (49). The constructs that a person develops are bipolar in nature, for instance, ‘undeserving–deserving’ (p. 176) (50) and shape expectations and interpretation of events while being continually open to revision in response to experience (47). This process of construing itself falls on a ‘loose–tight’ continuum with extremes of very loose or very tight construing, constituting a threat to psychological well-being. ‘Loose’ construing occurs when an element is positioned on opposing ends of construct poles on different occasions and results in variable predictions and a disorganised view of the self and world (47). Conversely, excessively ‘tight’ construing results in consistent and precise but unvarying predictions with overly ‘tight’ construing resulting in ‘all or nothing’ thinking (51).

An advantage of RGT is that via elicitation of idiosyncratic definitions of elements and constructs, it can reveal implicit attitudes that may not be shared in interviews (52). Similarly, it can be used to detect clinically meaningful changes in construing following therapeutic interventions that cannot be identified by standard questionnaires (53). Overall, RGT enables a person’s subjective experience to be subjected to objective analysis, thereby reducing researcher bias (54).

As such, RGT has been effectively utilised in mental health research, particularly inpatient samples, including those experiencing psychosis, anxiety, and depression (49, 55–58), to examine changes in construing of people experiencing a mental health condition following therapeutic intervention (59–61). A key aspect of RGT in such studies is the facility to conduct idiosyncratic assessment across different time points with very small sample sizes of up to eight participants (59, 62, 63). Furthermore, Wittkowski et al. (64) used RGT to examine the experiences of compassionate care during an MBU admission.

No study to date has investigated the construals and construing in mothers at admission to an MBU and assessed for changes in construing following an MBU admission, to explore the clinical benefits of MBU care in supporting maternal mental health. Using the RGT, the preliminary aim of this current study was to assess how mothers who experienced an acute mental health crisis that necessitated MBU care construed themselves at admission. Furthermore, this exploratory study sought to answer the following question: “How does a mother’s self-concept, captured through the way she construes herself, particularly how she construes herself as a mother, change during an admission to an MBU?”.

2 Materials and methods2.1 DesignThe study utilised a within-subject repeated measures design, with participants acting as their own control. It used RGT (46) to investigate maternal construal and process of construing at admission, and then assess for change to these areas during an MBU admission.

2.2 Ethical and other approvalsRelevant approvals were obtained from the NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) and Health Research Authority (HRA) (reference: 23/WA/0020), and local NHS Trusts Research and Innovation departments (reference: x648). In line with UK legislative frameworks for best practice, experts by experience were consulted on the research design process (65). We liaised with at least one member of the University’s Community Liaison Group (its members include services users, people with lived experiences, and carers) in the development stage of this study, who recognised the potential benefits of this study and advised on some procedural aspects.

2.3 Participant inclusion and exclusion criteriaParticipants, considered eligible for inclusion, were 1) aged 18 years or over, 2) admitted to a participating MBU within the last 4 weeks, 3) presenting with any mental health diagnosis, 4) pregnant or had delivered a baby in the last 12 months, 5) proficient in the English language, and 6) able to give informed consent. RGT methodology is not language-specific, but given limited resources to facilitate appropriate translation services, participants not fluent in English were excluded.

2.4 Recruitment and settingParticipants were recruited from two MBUs across two NHS Trusts in the Northwest of England between March 2023 and February 2024. The 8–10-bed MBUs provided similar specialist care, and the staff teams on both units comprised psychiatric and medical staff, psychiatric nurses, nursery nurses, clinical psychologists, and occupational therapists.

Participants were recruited via two main methods. Firstly, interested participants were able to contact the main researcher directly following study advisements to register an interest in taking part. On contact, a participant information sheet was shared. Alternatively, ward-based clinical staff identified potential participants and asked them to complete a consent to contact form if they were interested in participating. On receipt of the consent to contact form or self-directed contact, the main researcher then contacted the potential participant and ascertained eligibility, and the first assessment session was arranged.

2.5 Questionnaire data collectionA demographic questionnaire, specifically designed for this study, was used alongside the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation - Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) (66) to contextualise individual experiences and the sample of participants. The CORE-OM is a 34-item self-report measure which assesses a person’s current psychological global distress, and the efficacy and effectiveness of psychological intervention (67). Responses on the scale range from 0 (not at all) to 4 (most or all the time), yielding possible scores between 0 and 136. For a total score of current psychological global distress, a score of 1–20 is deemed a ‘healthy’ level of distress and a score of 85+ indicates a ‘severe’ level of distress. The CORE-OM was scored in line with standardised scoring procedures (68) and was based on the mean rating applied to each sub-scale, with a score of 1.00 or above indicative of exceeding the clinical cut-off. The CORE-OM is recommended for UK perinatal mental health services (69) and has good internal reliability, test–retest reliability, convergent validity with other measures, and sensitivity to change (67). Furthermore, the CORE-OM can successfully assess change in clinical recovery (70).

2.6 Repertory grid procedureTo develop the repertory grid, participants were presented with the following 10 elements: 1) actual (current) self, 2) ideal self, 3) actual (current) self as mother, 4) ideal self as mother, 5) ideal other mother, 6) other mother on MBU, 7) friend I know who is a mother, 8) self before becoming a mother, 9) ideal future self, and 10) ideal future self as a mother. These elements were based on the repertory grid literature (46, 52) and their relevance to the perinatal field and were predetermined by the authors, who have expertise in utilising repertory grid methodology and working clinically in mental health. The triadic difference method was used to generate bipolar constructs (54, 71) and involved presenting the participant with three randomly selected elements at one time and asking them to consider “How are two of these similar to one another (emergent construct) and different from the third (implicit construct)?”. Participants were then asked to describe in detail and give behavioural examples of each construct pole that had been developed to ensure the specific meaning was identified. This process was repeated to ensure each element was used to generate constructs at least once, and until the participant was unable to generate any more constructs. The participant was then asked to select the construct end which was preferred and to rank each element along the elicited construct poles, using a 10-point scale, to generate the repertory grid. The ranking approach was chosen over alternative methods, such as rating elements on a Likert scale, to ease the procedural load on participants who were presenting with significant mental health difficulties. Elements used to elicit the construct were rated first and the remaining elements randomly thereafter. To maintain anonymity, the elements were identified by initials. The same elements were used to allow greater comparability across multiple-participant grids. On repetition of the repertory grid at the second assessment session, the same elements and same constructs developed and utilised at the first assessment session were used, which enabled comparison of a participant’s repertory grids across time, to explore for commonalities and differences.

2.7 ProcedureThe main researcher (EW), who was not an MBU staff member and hence conducted the study independently, completed two assessment sessions with participants at two time points to enable construing to be captured at admission and then discharge, with the intention of attributing change in construing specifically to the MBU admission. In the current study, the therapeutic intervention was defined as the admission to an MBU. The first assessment session took place within the first 4 weeks of admission, allowing participants time to settle on the ward and for acuity of difficulties to lessen. The second assessment session took place at discharge or up to 3 months post discharge. The procedure for assessment sessions one and two were identical, and the same repertory grid was used at each assessment session. The assessment sessions used a one-to-one format, each lasting 45 min–120 min. Assessment sessions were arranged for a convenient time for the participant. After providing informed consent, participants were asked to firstly complete the demographic questionnaire, followed by the CORE-OM (66), and then time was spent developing and completing the repertory grid. Following each assessment session, participants were provided with a debrief form and an e-voucher worth £10 each to thank them for their time and participation.

2.8 Data analysisDemographic data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences v29.0 (72). CORE-OM scores were produced at admission and discharge, and the numerical difference in the CORE-OM scores between administrations was calculated. A Reliable Change Index (RCI) was used to assess for reliable change in the level of psychological global distress over time. For the degree of change to be classified as reliable, the change in the mean rating applied to sub-scales must have been greater than 0.5 (73). Demographic data and CORE-OM scores were then tabulated.

Individual repertory grids were analysed using the repertory grid analysis package Idiogrid version 2.4 (74). Principal component analysis (PCA) (75) was then performed on each participant’s admission repertory grids and, if available, discharge repertory grids, to explore construing at each time point (52). The process of construing was established using the eigenvalue, i.e., the percent variance accounted for by the first principal component, with eigenvalues categorised as ‘tight’ or ‘loose’, with a greater eigenvalue indicative of ‘tighter’ construing (51). Observations were made between eigenvalues obtained from admission and discharge grids, to assess construing at admission, and the evidence of any change in construing over time. Changes in eigenvalues were subjected to further analysis (i.e., Wilcoxon signed rank test) to assess the significance of any changes observed.

To explore construal at admission and discharge, Slater analysis (76) (Slater, 1967) was used to establish the mean Euclidean distance between pairs of elements of interest from all repertory grids. The use of the same elements and constructs during both repertory grid administrations enabled differences in Euclidean distance between elements to be measured across time. Elements deemed to be construed as very similar were those in which the inter-element Euclidean distance was less than 0.5, whereas those deemed as highly dissimilar had a distance greater than 1.50 (51). The Euclidean distance between the following pairs of elements were calculated: a) actual (current) self as mother and ideal self as mother, to establish a measure of self-esteem as a mother; b) actual (current) self and ideal self, to establish a measure of self-esteem; c) actual (current) self as mother and non-self elements, to assess the construal of non-self elements; and d) self before becoming a mother, ideal self, and actual (current) self, to explore the construal of self before becoming a mother.

To ascertain construal at admission and assess for any change over time, yielded by the PCA (75), the mean ranked position of specific elements on each elicited construct pole and elements’ mean ranked position comparative with other elements were calculated on all repertory grids. The higher the mean ranked position, the more closely the negative pole of the construct (non-preferred) applied to the element. This analysis facilitated exploration of self-perception, by studying whether the actual (current) self and the actual (current) self as mother tended to be construed more positively or negatively. In addition, construal of non-self elements, by investigating how the actual (current) self as mother, other mother on MBU and friend I know who is a mother were positioned relative to one another along construct dimensions.

Change in construing over the period of MBU admission was calculated by establishing changes in the Euclidean distance between the pairs of elements of interest and changes to the mean ranked position of elements along elicited construct poles between the admission and discharge repertory grids of each participant. Changes in Euclidean distances and mean ranked position of elements along elicited construct poles were subjected to further analysis (i.e., Wilcoxon signed rank test) to assess the significance of any changes observed.

Finally, content analysis was conducted across all repertory grids, using the Classification System for Personal Constructs (CSPC) (77) to explore commonality in the elicited constructs. This analysis involved categorising all constructs elicited by participants into one of eight areas, six comprehensive areas, and two supplementary areas (77): 1) Moral, 2) Emotional, 3) Relational, 4) Personal, 5) Intellectual/Operational, 6) Values/Interests, 7) Existential (supplementary area), and 8) Concrete (supplementary area).

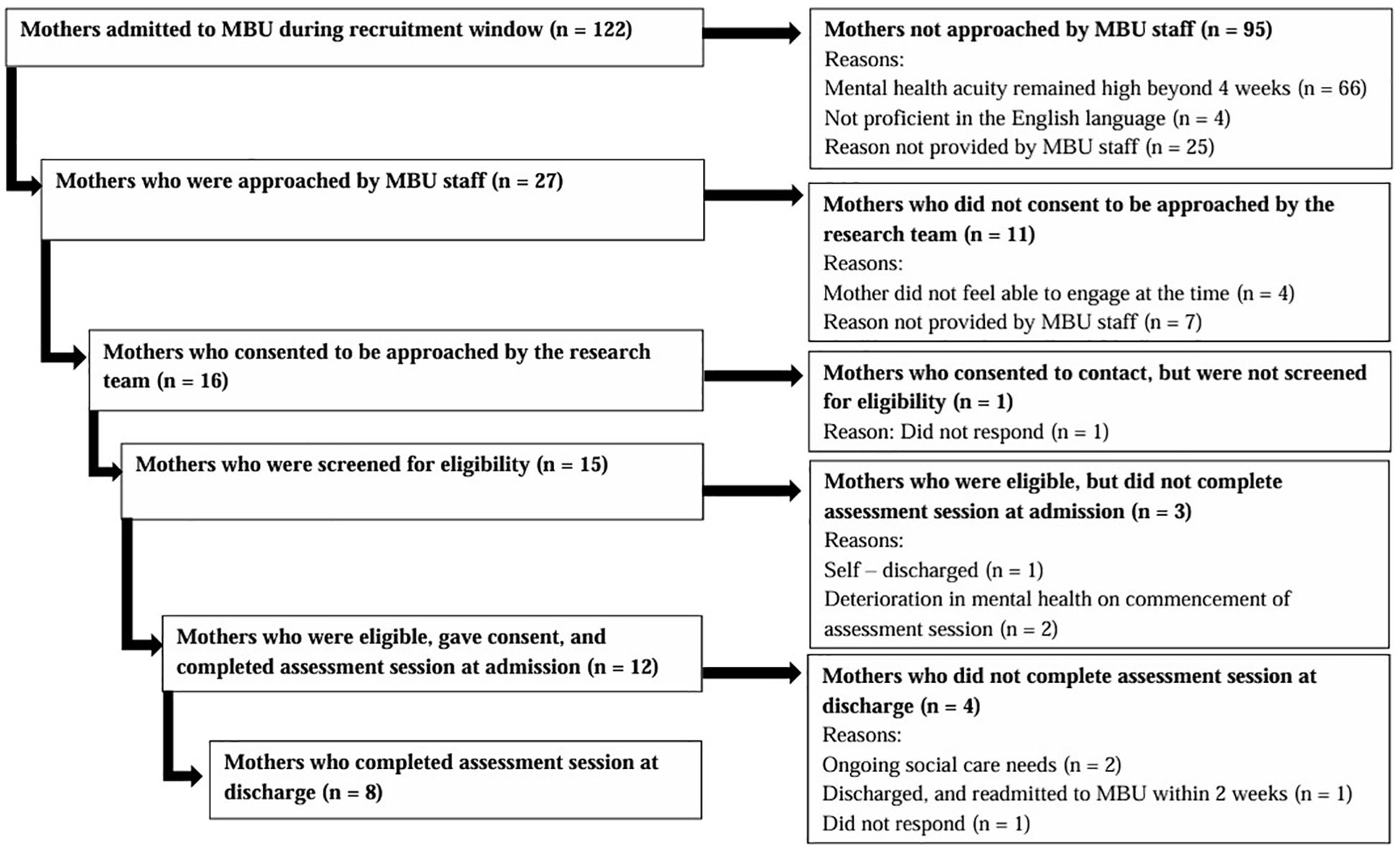

3 Results3.1 Participant characteristicsFigure 1 illustrates the number of mothers admitted to the MBUs during study duration and the flow of participants through the study. Eight participants completed the RGT assessment session at admission and discharge. Four participants undertook the admission RGT assessment session only for various reasons including ongoing social care needs that affected their engagement (n = 2), readmission to an MBU within 2 weeks of discharge rendering them ineligible (n = 1), and not responding to contact from the research team (n = 1). There were 11 of the 12 participants who were admitted to one of the two MBUs utilised for recruitment, and all participants who completed RGT assessment sessions at discharge were admitted to the same MBU. All participants were recruited by one recruitment method and were identified by MBU staff as potential participants (n = 12). All admission RGT assessment sessions took place on the MBU (n = 12), whereas discharge assessment sessions were conducted either on the MBU (n = 4), or in person, at the participant’s home (n = 4), depending upon participant preference.

Figure 1. Consort diagram illustrating flow of MBU participants through the study.

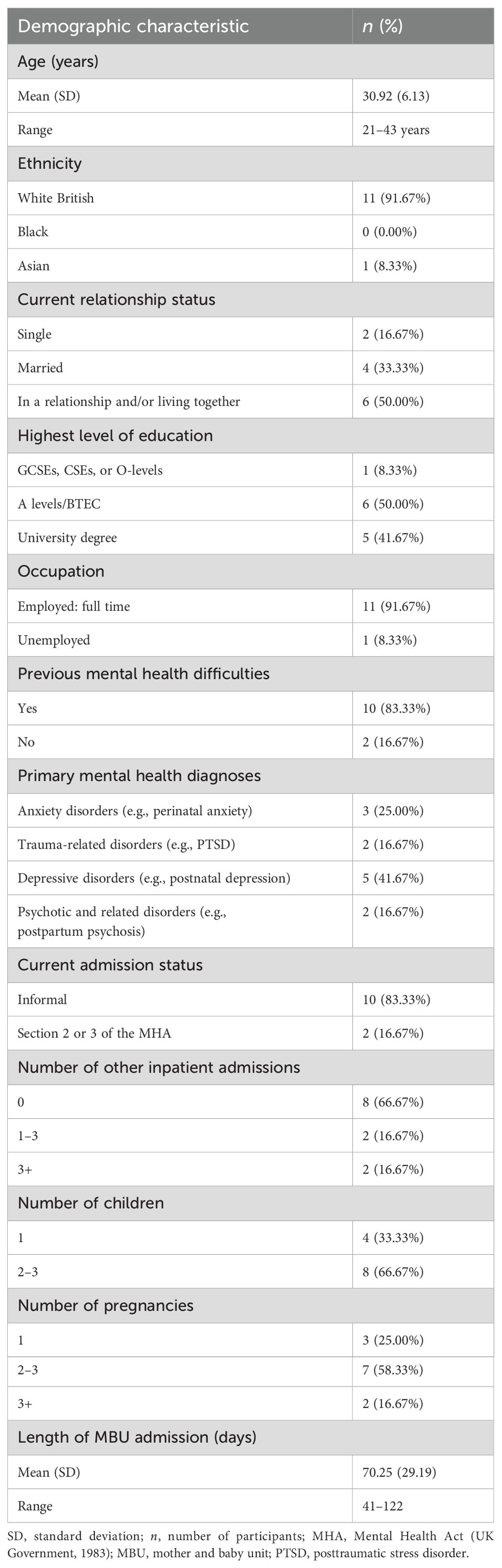

The demographic characteristics of all 12 participants are displayed in Table 1. Participants were aged 21 to 43 years (M = 30.92, SD = 6.13), and almost all described their ethnic origin as White British (n = 11). Most participants were either married (n = 4) or in a relationship with the father of their child (n = 6). Most participants were also employed full-time (n = 11), and all employed participants were on maternity leave at the time of participating in the study. Education was achieved to GCSE (n = 1), A-Level/BTEC (n = 6), and university degree (n = 5).

Table 1. The demographic characteristics of all 12 participants.

Prior to the current episode of mental ill health, most participants expressed experiencing previous mental health difficulties (n = 10). Although for most participants, this was their first hospital admission (n = 8). Participants were often diagnosed with more than one condition; however, primary diagnoses included depressive disorders (n = 5), anxiety disorders (n = 3), trauma-related disorders (n = 2), and psychotic-related disorders (n = 2). The duration of MBU admission for participants ranged between 41 and 122 days (M = 70.25, SD = 29.19). The majority of participants were informally admitted to the MBU (n = 10), and only two participants were admitted under a section of the Mental Health Act (78) (MHA; UK Government, 1983).

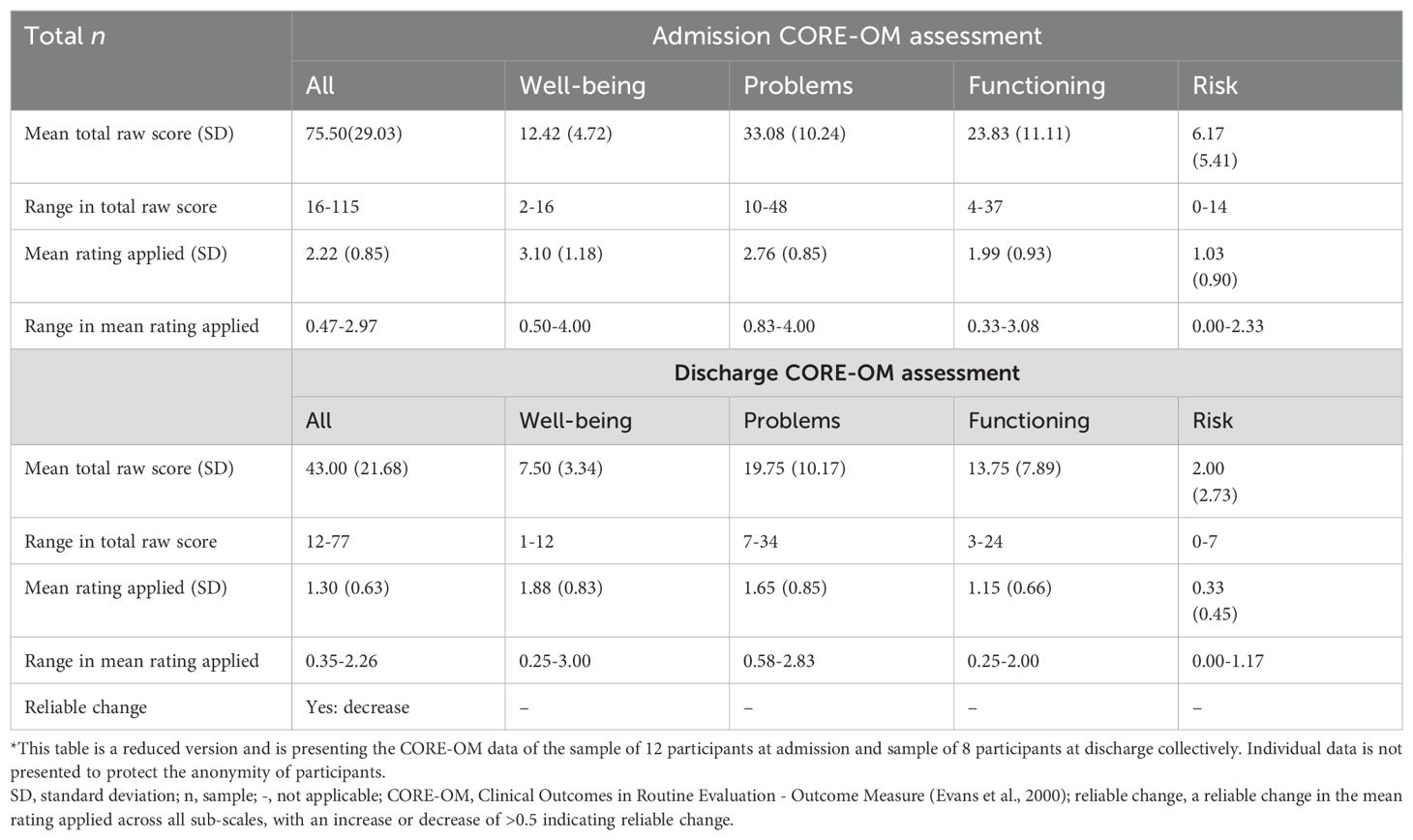

3.2 Psychological distress from questionnaire dataAt admission, the overall mean rating applied to all sub-scales for the sample of 12 participants was above the clinical cut-off (M = 2.22, SD = 0.85; see Table 2); however, there was a range in the mean rating applied to all sub-scales between 0.47 and 2.97. At discharge, the overall mean rating applied to all sub-scales remained above the clinical cut-off for the sample of eight participants (M = 1.30, SD = 0.63), and the mean rating applied to all sub-scales ranged between 0.35 and 2.26. In accordance with the RCI, there was a reliable decrease in the mean rating applied to all sub-scales between admission and discharge.

Table 2. Clinical outcome data for admission and discharge.

Of the eight participants who completed admission and discharge grids, seven demonstrated a decrease greater than 0.5 in the mean rating applied to all sub-scales, indicating that these participants exhibited reduced levels of global psychological distress over the course of their MBU admission. Three of these seven participants showed a mean rating applied to all sub-scales at discharge, which was below the clinical cut-off for heightened psychological distress. One participant showed an increase in this score; however, this was a non-reliable change (i.e., <0.5 increase in mean rating applied to all sub-scales).

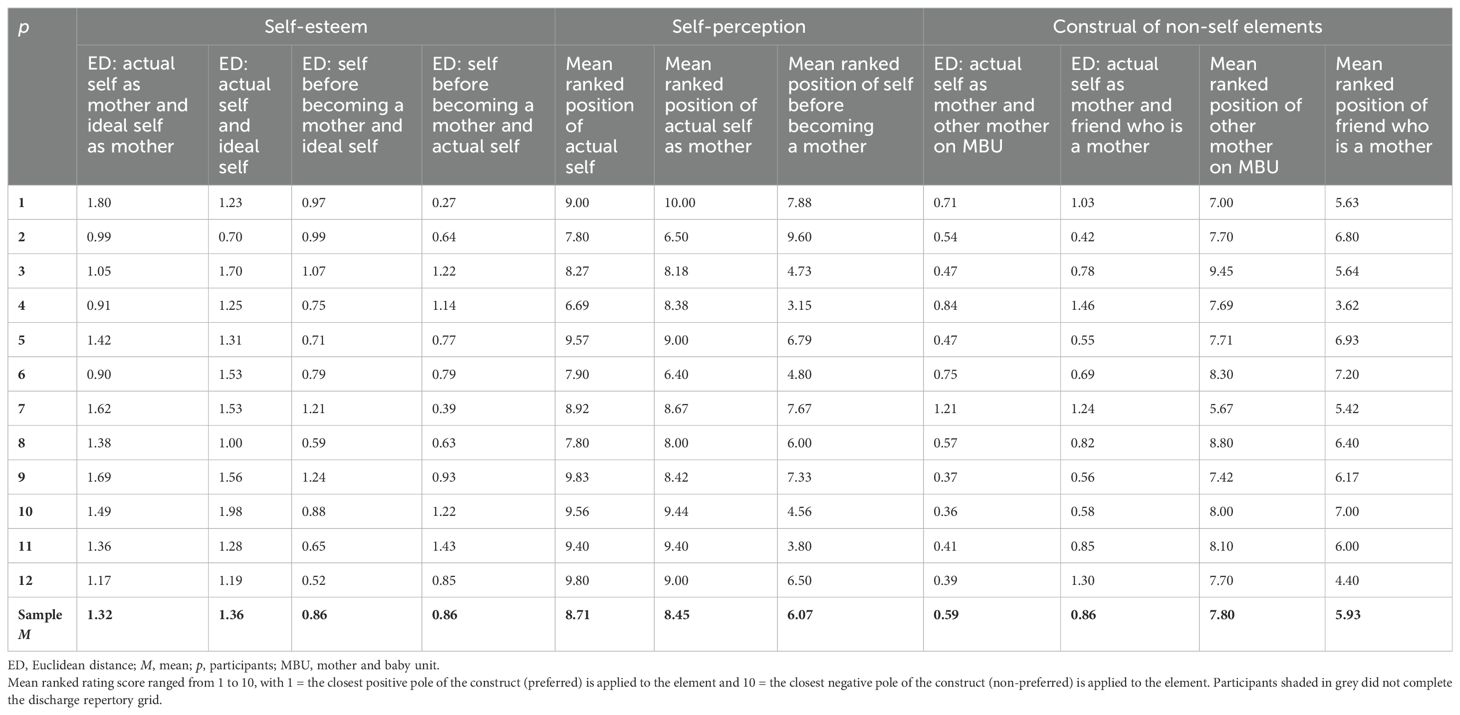

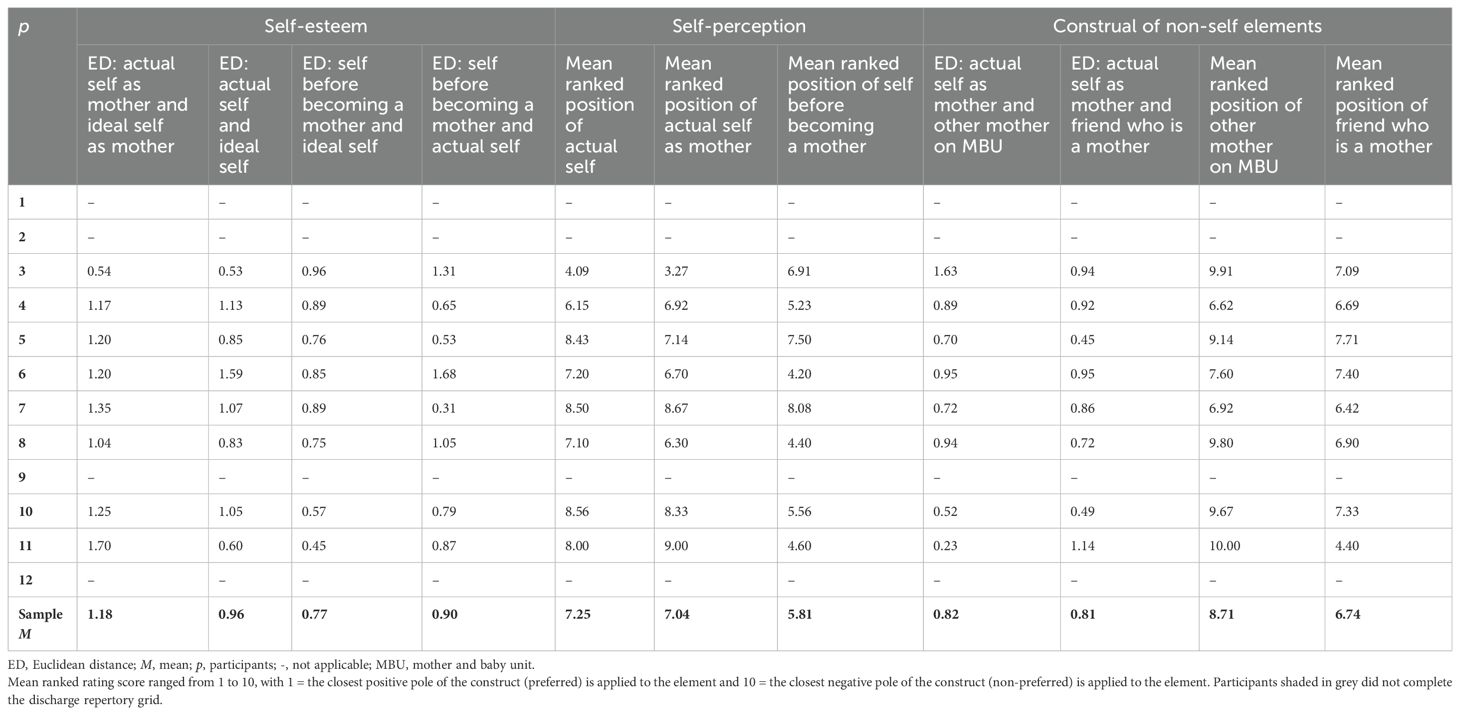

3.3 Summary of repertory grids3.3.1 Self-esteem, self-perception, and construing of non-self elements at admissionParticipants tended to experience low self-esteem at admission to the MBU, indicated by a high level of dissimilarity between the actual current self and the ideal self (sample M Euclidean distance = 1.36; see Table 3); this pattern of construing was observed for all 12 participants. Similarly, participants presented with low self-esteem as a mother at admission, illustrated by a high level of dissimilarity between the actual current self as mother and the ideal self as mother (sample M Euclidean distance = 1.32). No participant construed the actual current self as mother and the ideal self as mother as highly similar at admission (i.e., a Euclidean distance of <0.5 between these two elements). Participants tended to construe the actual current self (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 8.71) and the actual current self as mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 8.45) extremely negatively. These findings implied that they held a highly negative self-perception for both their holistic self and their self as a mother at admission.

Table 3. Euclidean distances (standardised) and mean ranked ratings used to calculate self-esteem, self-perception, and construal of non-self elements at admission.

Participants tended to construe greater similarity between the actual current self as mother and the other mother on the MBU (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.59), relative to the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.86) at admission, with the exemption of two participants (p numbers are withheld throughout to protect participant anonymity) who did not demonstrate this pattern of construing. These findings suggested that, in general, participants tended to construe themselves as more similar to another mother with a mental health condition that necessitated an inpatient admission, compared with a friend who is a mother, residing in the community. All participants construed a friend who is a mother more positively (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 5.93) than the other mother on the MBU (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 7.80). All 12 participants construed a friend who is a mother more positively than the actual current self (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 8.71), and 10 participants also construed this non-self element more positively than the actual current self as mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 8.45). The same two participants mentioned above demonstrated an opposite pattern of construing to most participants, construing the actual current self as mother more positively than a friend who is a mother. Participants construed the other mother on the MBU more positively than the actual current self, with the exception of four participants. Similarly, participants construed the other mother on the MBU more positively than the actual current self as mother; however, three of the same participants, alongside another participant, did not demonstrate this pattern of construing.

Self before becoming a mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 6.07) was construed more positively than both the actual current self and the actual current self as mother by all but one participant, suggesting that participants generally held a positive perception of their past self. Participants construed the self before becoming a mother more positively than the other mother on the MBU, except for three participants. Despite the sample mean ranked position along construct poles being greater for the self before becoming a mother (sample M = 6.07) than a friend who is a mother (sample M = 5.93), seven participants construed the self before becoming a mother more positively compared with a friend who is a mother. Therefore, the current findings indicated that participants admitted to an MBU tended to construe the self before becoming a mother more positively than both non-self elements. Interestingly, the self before becoming a mother was construed as equally dissimilar to the ideal self (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.86) and the actual self (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.86).

Overall, participants experienced low self-esteem in general and low self-esteem as a mother, in conjunction with a negative self-perception, at admission to an MBU. In addition, participants with a low self-esteem and a negative self-perception at admission also perceived their past self positively. They construed mothers who were not accessing support from an MBU for their mental health needs more positively compared with mothers who required psychiatric inpatient admission. Then, respectively, participants generally construed other mothers accessing MBU support more positively, compared with themselves; however, this was not a pervasive finding throughout the sample of 12 participants. Together, these findings suggested that participants typically construed other mothers in general, irrespective of whether they were admitted to an MBU or not, more positively, compared with how they construed themselves. Moreover, participants tended to construe themselves as more similar to the other mothers on the MBU compared with a friend, inferring that participants generally construed greater similarity between themselves and the non-preferred non-self element. In the instances where participants construed the other mothers on the MBU more negatively relative to themselves, some of these participants did demonstrate the pattern of construing whereby the actual current self as mother was construed as more similar to the non-self element that was perceived negatively (i.e., other mother on the MBU). Therefore, despite not illustrating the common pattern of construing, i.e., the other mother on the MBU being perceived more positively relative to the self, the pattern of construing that was exhibited substantiated the notion that participants tended to hold a negative self-perception at admission.

Some specific observations were noted. One participant did not demonstrate some of the typical patterns of construing observed in the sample. Firstly, she held a more positive self-perception for her current self as a mother, as demonstrated by more positive construing of the actual current self as mother, compared with both non-self elements. She also construed the actual current self as mother as more similar to a friend who is a mother, the non-self element she construed more positively, compared with the other mother on the MBU. To offer more understanding for this pattern of construing, contextual information showed that this mother had been engaging in intensive psychological therapy prior to admission to the MBU, which she reflected had provided several therapeutic benefits. She shared her appreciation for her ‘internal strength’ and reflected on a sense of ‘personal pride,’ in relation to managing internal distress. This contextualisation lends support to the previous inference that construing the self negatively tended to associate with construing the self as more similar to the other mother on the MBU, who was construed negatively.

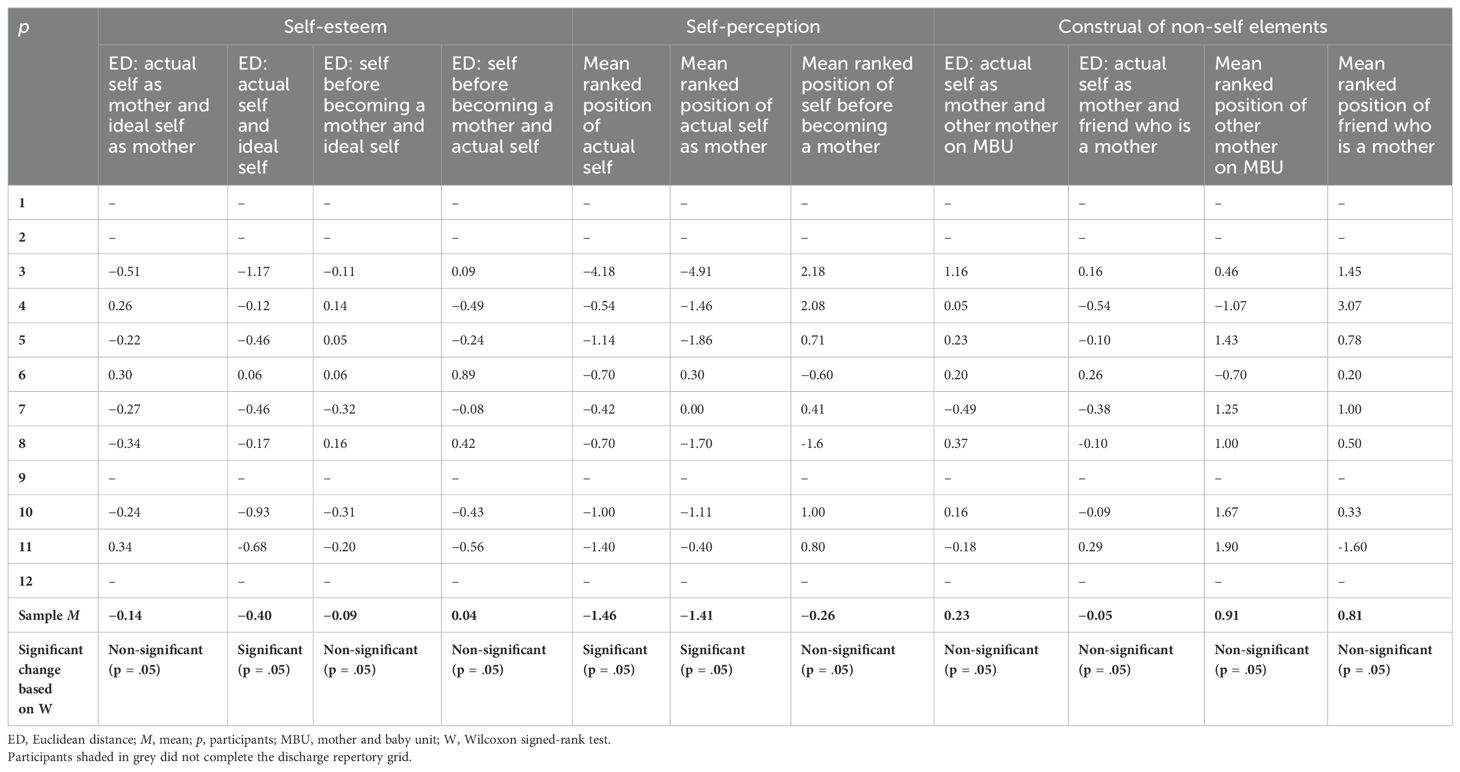

3.3.2 Self-esteem, self-perception, and construing of non-self elements at discharge and change during MBU admissionOf the 12 participants who completed admission repertory grids, eight participants completed discharge repertory grids (see Figure 1). Discharge repertory grids were subjected to Slater analysis, to calculate construal at discharge (see Table 4). Comparisons between admission and discharge grids were then made and numerical values extracted from the repertory grids examined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to explore any changes in construal during MBU admission (see Table 5).

Table 4. Euclidean distances (standardised) and mean ranked ratings used to calculate self-esteem, self-perception, and construal of non-self elements at discharge.

Table 5. Changes to the Euclidean distances (standardised) and mean ranked ratings used to calculate self-esteem, self-perception, and construal of non-self elements between admission and discharge.

Seven of the eight participants in this sample showed an improvement in their self-esteem during their MBU admission (sample M Euclidean distance change = −0.40, Z = 1, p = .05). This improvement was not observed for one participant, whose self-esteem appeared to decrease over time. Self-esteem as a mother also improved from admission to discharge for five participants, illustrated through a reduction in the Euclidean distance between the actual current self as mother and the ideal self as mother (sample M Euclidean distance change = −0.14, Z = 14.5, p = n.s.). However, a conflicting pattern of change in construing was observed in three participants, who demonstrated a reduction in their self-esteem as a mother during their MBU admission. It is important to emphasise that despite showing an improvement in their self-esteem as a mother over time, one participant in particular continued to construe extreme dissimilarity between the actual current self as mother and the ideal self as mother at discharge (i.e., a Euclidean distance of 1.35 between these two elements). Despite the improvements in self-esteem in general and in the maternal role, participants tended to continue to experience low self-esteem in general and in their maternal role at discharge from the MBU, as illustrated by dissimilarity between the actual current self and the ideal self (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.96) and the actual current self as mother and the ideal self as mother (sample M Euclidean distance = 1.18).

Participants construed themselves more positively at discharge, both themselves generally (sample M ranked position along construct poles change = −1.46, Z = 0, p = .05) and themselves as a mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles change = −1.41, Z = 1, p = .05), relative to admission. This pattern of holding a more positive self-perception was observed in all participants, with the exception of two participants’ views of the actual current self as mother, when no or very small changes to the mean ranked position of element along construct poles were observed. However, most of the eight participants continued to construe the actual current self (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 7.25) and the actual current self as mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 7.04) fairly negatively, suggesting participants persisted to hold a negative self-perception at discharge.

Participants generally continued to construe the self before becoming a mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 5.81) positively, relative to current versions of the self. An exemption to this was in the instance of one participant who construed the actual current self more positively than the self before becoming a mother at discharge. The same participant also construed the actual current self as mother more positively than the self before becoming a mother, alongside another participant. Six participants were observed to construe the self before becoming a mother more negatively at discharge relative to admission (sample M ranked position along construct poles change = −0.26, Z = 8, p = n.s.). Self before becoming a mother was construed more positively than a friend who is a mother by all participants except two. One of these two participants was also the only participant who construed the self before becoming a mother more negatively than the other mother on the MBU at discharge. Participants generally construed the self before becoming a mother as more similar to the ideal self (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.77) than the actual self (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.90) at discharge; however, three participants did not demonstrate this pattern of construing.

At discharge, participants appeared to construe the actual current self as mother as slightly more similar to a friend who is a mother (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.81) than the other mother on the MBU (sample M Euclidean distance = 0.82), although three participants did not. For a different participant, there was no difference in the conceptual distance between the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother and the actual current self as mother and the other mother on the MBU. Overall, the conceptual distance between the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother was observed to decrease during MBU admission (sample M Euclidean distance change = −0.05, Z = 15, p = n.s.). Differences to this pattern of change in construing were observed in three participants, with these participants construing themselves as increasingly dissimilar to a friend who is a mother over time. Despite an increase in conceptual distance between the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother during admission, one of these three participants did construe the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother as more similar than the actual current self as mother and the other mother on the MBU at discharge. Except for two participants, participants construed the actual current self as mother and the other mother on the MBU as increasingly dissimilar during admission (sample M Euclidean distance change = 0.23, Z = 10, p = n.s.). These two participants construed themselves as increasingly alike the other mother on the MBU at discharge, relative to how this element pair were construed at admission.

Overall, participants continued to construe a friend who is a mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 6.74) relatively positively, and seven participants construed a friend who is a mother more positively than the other mother on the MBU (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 8.71); only one participant did not demonstrate this pattern. Six participants construed the other mother on the MBU most negatively, when comparing against the actual current self as mother, the actual current self, and a friend who is a mother. According to the sample means, participants construed a friend who is a mother more positively than the actual current self as mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles = 7.04) at discharge; however, half of the participants construed the actual current self as mother most positively, in comparison with the actual current self and both non-self elements. Only one participant construed the actual current self as mother and the actual current self, more negatively than both non-self elements at discharge. Generally, participants construed the non-self elements, a friend who is a mother (sample M ranked position along construct poles change = 0.81, Z = 7, p = n.s.), and the other mother on the MBU (sample M ranked position along construct poles change = 0.91, Z = 6, p = n.s.), more negatively over their MBU admission. However, variations to this pattern of change in construing were observed in two participants, who construed the other mother on the MBU more positively during admission, and one different participant who construed a friend who is a mother more positively over time.

3.3.3 Construal profiles of motherParticipants appeared to fall into one of two possible groups of changes in construing during MBU admission, which were termed in this study as Profiles. However, it is important to highlight that some participants appeared to show changes in construing consistent with both profiles. Profile 1 was characterised by an improvement in self-esteem, both in general and in the maternal role. These participants construed the actual current self as mother more positively than the other mother on the MBU and often more positively than a friend who is a mother, during their MBU admission. At discharge, a friend who is a mother continued to be construed more positively than the other mother on the MBU. These participants construed greater similarity between the actual current self as mother and a friend who is a mother, in comparison with the actual current self as mother and the other mother on the MBU at discharge. While subtle deviations from this overall profile were present, these changes in construing seemed to occur for five of the eight participants. Participants who showed changes in construing in line with profile 1 typically had experiences including a supportive network of family and friends who visited the ward regularly. These participants readily engaged in the therapeutic offer on the ward and were able to follow a graded discharge plan. For most of these participants, this was their first inpatient psychiatric admission and all of these participants were admitted to the MBU informally.

Profile 2 was characterised by a reduction in self-esteem, specifically in the maternal role. A friend who is a mother continued to be construed more positively than the actual current self as a mother and the other mother on the MBU; both were construed negatively. These participants construed the actual current self as mother as increasingly similar to the other mother on the MBU, compared with a friend who is a mother, over time. Two participants demonstrated changes in construing consistent with this profile, and in most aspects, a third participant did. Participants who exhibited changes in construing in line with profile 2 typically had experiences including a ‘lonely,’ ‘critical,’ and ‘unsupportive’ living and/or family environment, high economic deprivation, social services involvement and were admitted to the MBU under a section of the Mental Health Act (78). These participants often had a complex mental health history, perceived their mental health condition as highly impairing, and had past psychiatric inpatient admissions. Furthermore, for these participants their admission meant they were more geographically isolated from family and/or friends resulting in a difficulty to experience regular visits from family and partners or follow a discharge plan that included initial brief visits home, which progressed into longer home visits.

One aspect of change in construing that presented in both profiles was the movement towards a more positive self-perception in general and as a mother. Positive self-esteem and a positive self-perception are often understood to hold a nuanced relationship; however, these findings suggested that there were intricate differences in what, when, and how self-esteem and self-perception were influenced and shaped during an MBU admission.

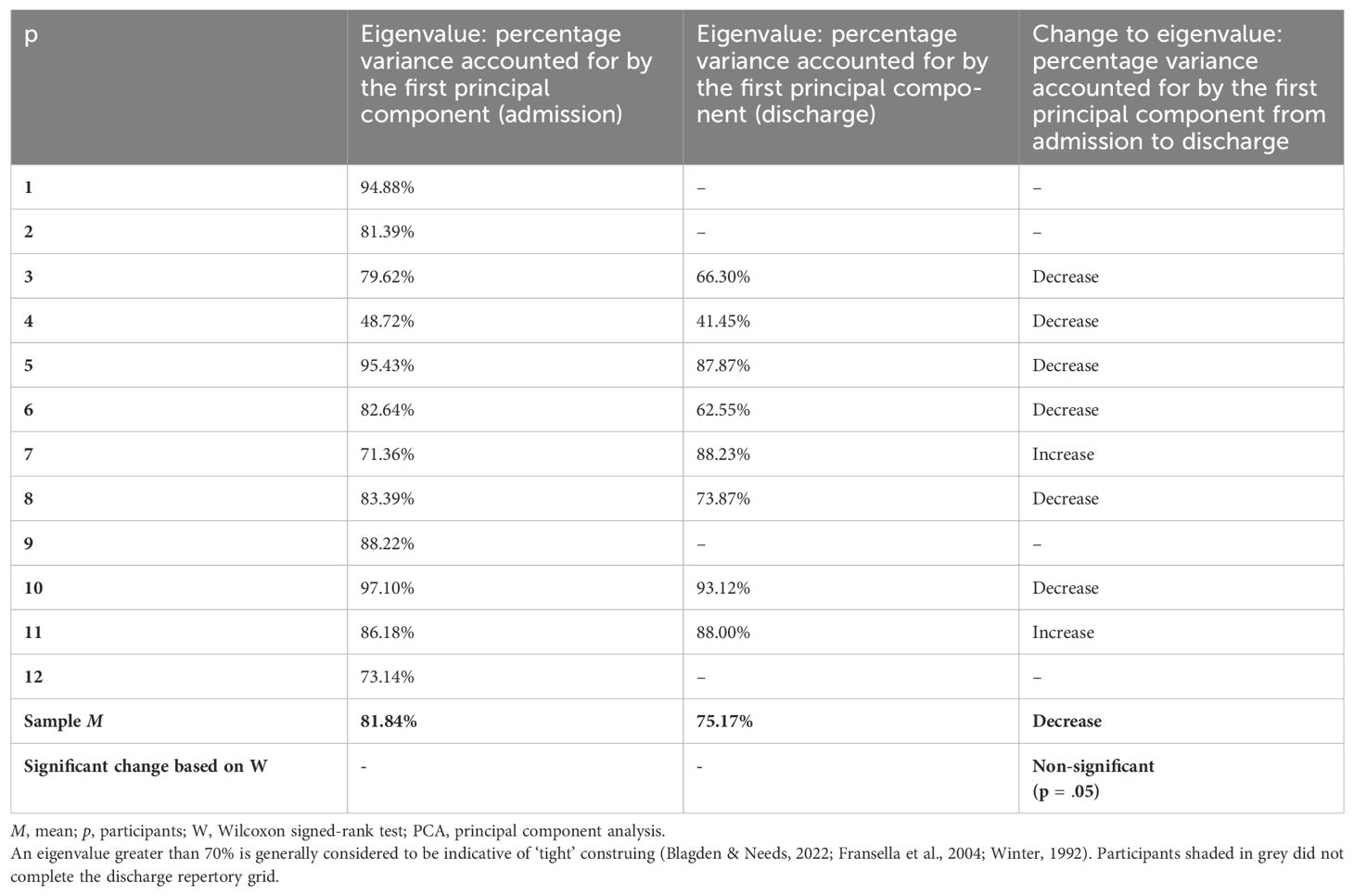

3.3.4 Construing at admission and dischargeThe mean percentage of variance accounted for by the first principal component at admission was high (sample M eigenvalue = 81.84%, SD = 13.27; see Table 6), with 11 of the 12 participants recording eigenvalues greater than 70%, which is indicative of ‘tight’ construing 46,51,78]. Only one participant presented with an eigenvalue indicative of ‘loose’ construing (eigenvalue = 48.72%).

Table 6. Construing reflected through percentage variance accounted for by the first principal component produced by the PCA.

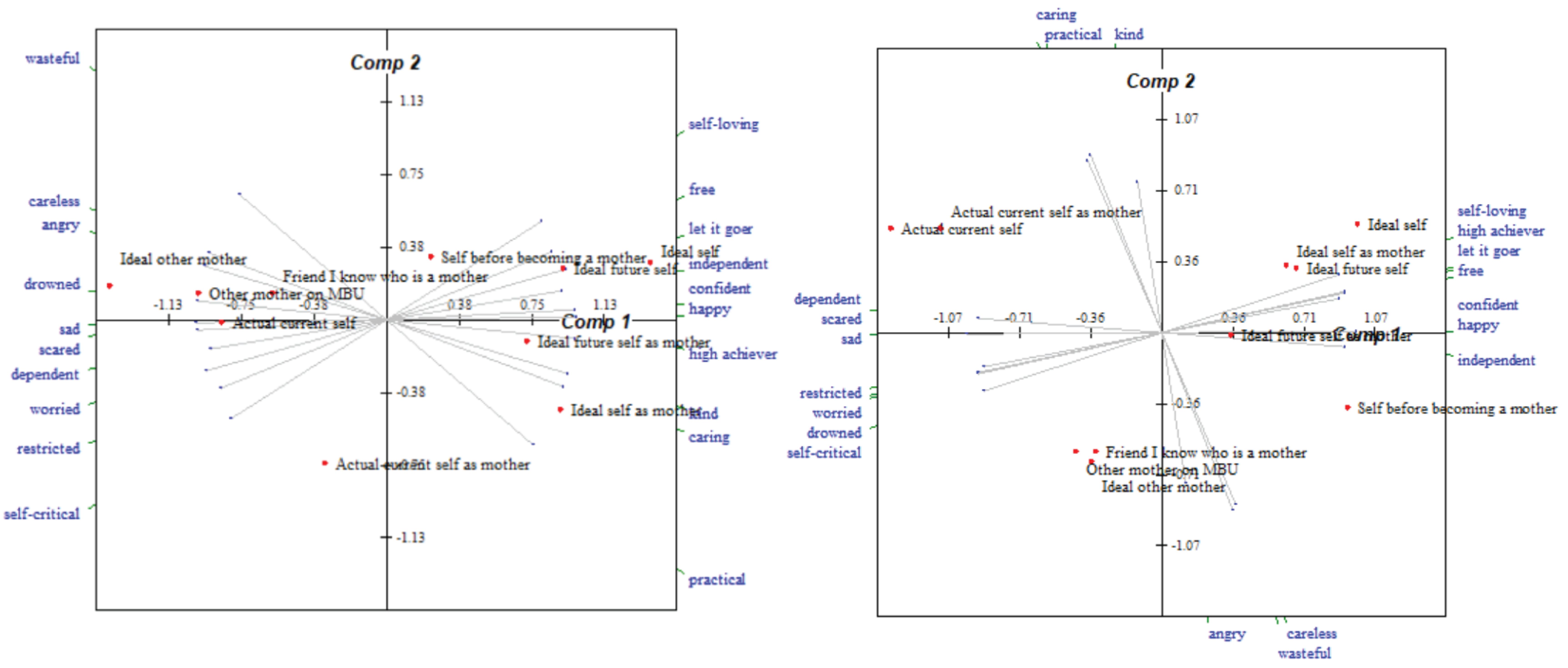

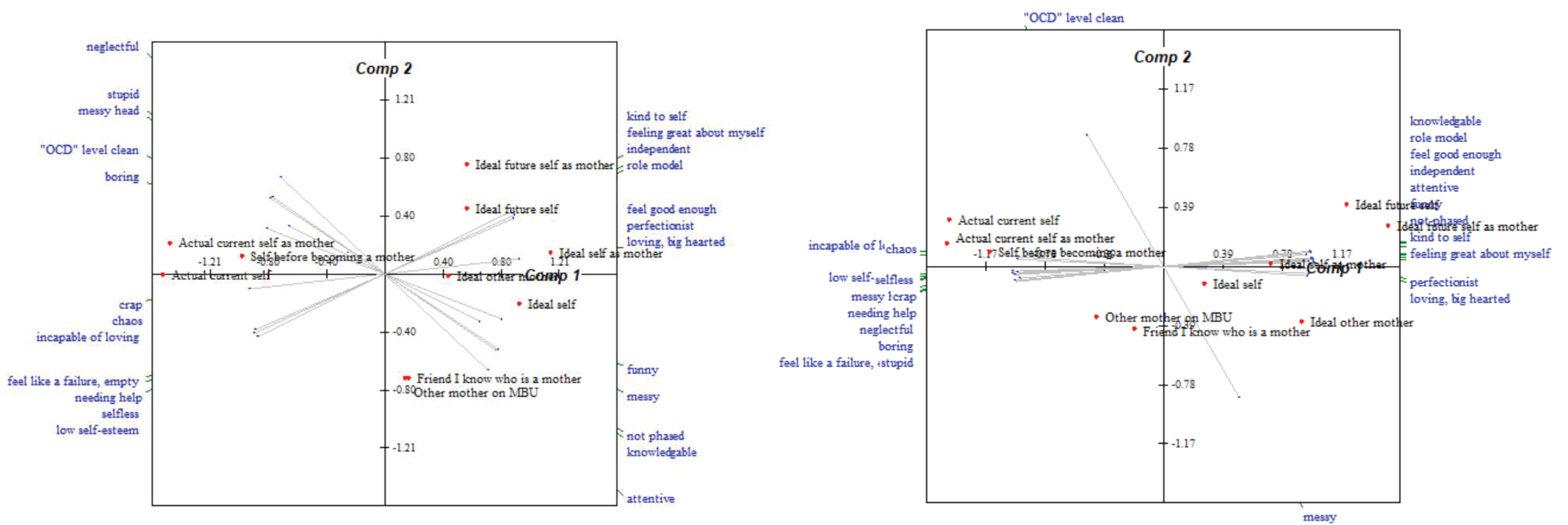

Construing appeared to ‘loosen’ for most participants between admission and discharge, as shown through a decrease in eigenvalues (sample M eigenvalue change = −6.67%, Z = 8, p = n.s.); however, overall, construing remained ‘tight’ at discharge (sample M eigenvalue = 75.17%, SD = 17.71). Of the eight participants who completed both admission and discharge repertory grids, six participants displayed ‘loosening’ of their conceptual system over the course of their admission. Of these six participants, three participants continued to demonstrate an eigenvalue greater than 70%. Comparatively, two participants showed an increase in eigenvalue between admission and discharge grids, suggesting construing became ‘tighter’ over time. To illustrate the ‘loosening’ and ‘tightening’ of conceptual structure exhibited by two participants respectively, the relevant PCAs are illustrated in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 2. Bi-plots of a participant’s repertory grids completed at admission and discharge respectively, who displayed ‘loosening’ of the conceptual system during their MBU admission.

Figure 3. Bi-plots of a participant’s repertory grids completed at admission and discharge respectively, who displayed ‘tightening’ of the conceptual system during their MBU admission.

Of the six participants who displayed ‘loosening’ of their conceptual system over time, five of these participants also demonstrated changes in construing that were more in keeping with profile 1 discussed in 3.3.3 Construal profiles of mothers during their MBU admission. The two participants who showed ‘tightening’ of their conceptual structure were participants whose pattern of construing changed during admission in a manner more aligned with the second profile.

3.3.5 Construing and psychological distressOf the eight participants who completed discharge repertory grids, seven participants (87.50%) who showed a reliable improvement in psychological distress as captured by the CORE-OM (i.e., a decrease of >0.5 in mean rating applied across all sub-scales) also showed an improvement in their self-esteem in general. The participant (12.50%) who did not show an improvement in psychological distress (i.e., a non-reliable increase of <0.5 in mean rating applied across all sub-scales) showed a reduction in overall self-esteem over time. Of the six participants (75.00%) who displayed ‘loosening’ of their conceptual system, five of these participants (62.50%) showed an improvement in psychological distress over time. Both participants (25.00%) who displayed ‘tightening’ of their conceptual system also displayed an improvement in psychological distress.

3.3.6 Content of constructs at admissionAll 12 repertory grids developed at admission were subjected to content analysis. Overall, 129 constructs were elicited (see Table 7). M

留言 (0)