Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori, HP), a prevalent cause of chronic bacterial infections in humans, is responsible for various types of gastrointestinal disorders, including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastric cancer, and gastric-mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (Malfertheiner et al., 2017). Beyond these ailments, H. pylori has also been associated with non-digestive issues in children, such as short stature, refractory iron deficiency anemia, malnutrition, and halitosis (Jones et al., 2017). The eradication of H. pylori plays a key role in the management of these clinical infestations, demonstrating the urgent need for accurate detection methods for H. pylori, especially the methods with sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90% (Xiang et al., 2022).

The current diagnostic landscape for H. pylori infection in clinical settings is divided between non-invasive methods like the 13C-urea breath test (UBT), stool antigen test (SAT), and serological test, and invasive approaches that include bacterial culture, histopathological examinations, and the rapid urease test (RUT). These methods have trade-offs in terms of simplicity, speed, and accuracy (Malfertheiner et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2022). Non-invasive tests are generally safer for patients but often compromise on detection sensitivity and specificity. Because of its high accuracy, the UBT is currently recommended as the best method for test of H. pylori infection. However, this test also has its drawbacks, such as its high cost and need for mass-spectrometric analysis, which limited the application in remote or resource-limited settings. Moreover, the high risk of false-positive and false-negative discounted the wide employment of UBT. The SAT is also a preferred method for epidemiological study and screening tests because it is noninvasive, cost effective, and easy to perform. However, if patients are subjected to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment, the sensitivity of the tests decreased (Malfertheiner et al., 2017). Invasive methods can offer higher accuracy but require gastric biopsy samples, which necessitate endoscopic intervention (Atkinson and Braden, 2016; Chey et al., 2017; Chey and Wong, 2007; Hunt et al., 2011). Despite their reliability, bacterial culture and histopathological exams are hampered by their long turnaround times, complexity, and demand for skilled personnel, which constrain their widespread use and effectiveness in H. pylori detection, delaying eradication efforts (Xiang et al., 2022). Thus, easy-to-operation, simple, rapid, and sensitive methods for H. pylori diagnosis are yet to be developed.

Nucleic acid amplification (NAA)-based methods, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and isothermal amplification techniques, represent the forefront in diagnosing pathogens due to their rapid, sensitive, and high throughput capabilities. Although PCR and its derivatives are extensively employed for detecting various pathogens, including H. pylori, their utility is limited by the complexity and cost of thermocycler equipment and the need for specialized operators (Gingras and Maggiore, 2020; Liu et al., 2023; Rimbara et al., 2013; Saez et al., 2012). As a result, isothermal-based nucleic acid amplification methods, such as multiple cross displacement amplification (MCDA), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), were widely deployed for pathogen detection (Bogaerts et al., 2013; Saez et al., 2012). Their independence from complex equipment and compatibility with various detection formats—such as lateral flow biosensors (LFB), colorimetric readouts, and fluorescence signals—make them ideally suited for point-of-care (POC) settings and regions with limited resources (Cao et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2023).

In this study, we developed a portable detection platform for rapid and accurate detection of H. pylori in gastric antrum mucosa samples by coupling MCDA with nanoparticle-based LFB, termed HP-MCDA-LFB. Here, we elaborated the basic principle of the HP‐MCDA‐LFB assay, evaluated its analytical sensitivity and selectivity, and further validated the feasibility with gastric antrum mucosa samples from patients suspected of H. pylori infection. Our data suggested that HP‐MCDA‐LFB assay devised here could be completed within 1 h with high degree of sensitivity and specificity, highlighting that the HP‐MCDA‐LFB assay was a potential and promising tool for rapid and reliable diagnosis of H. pylori infection.

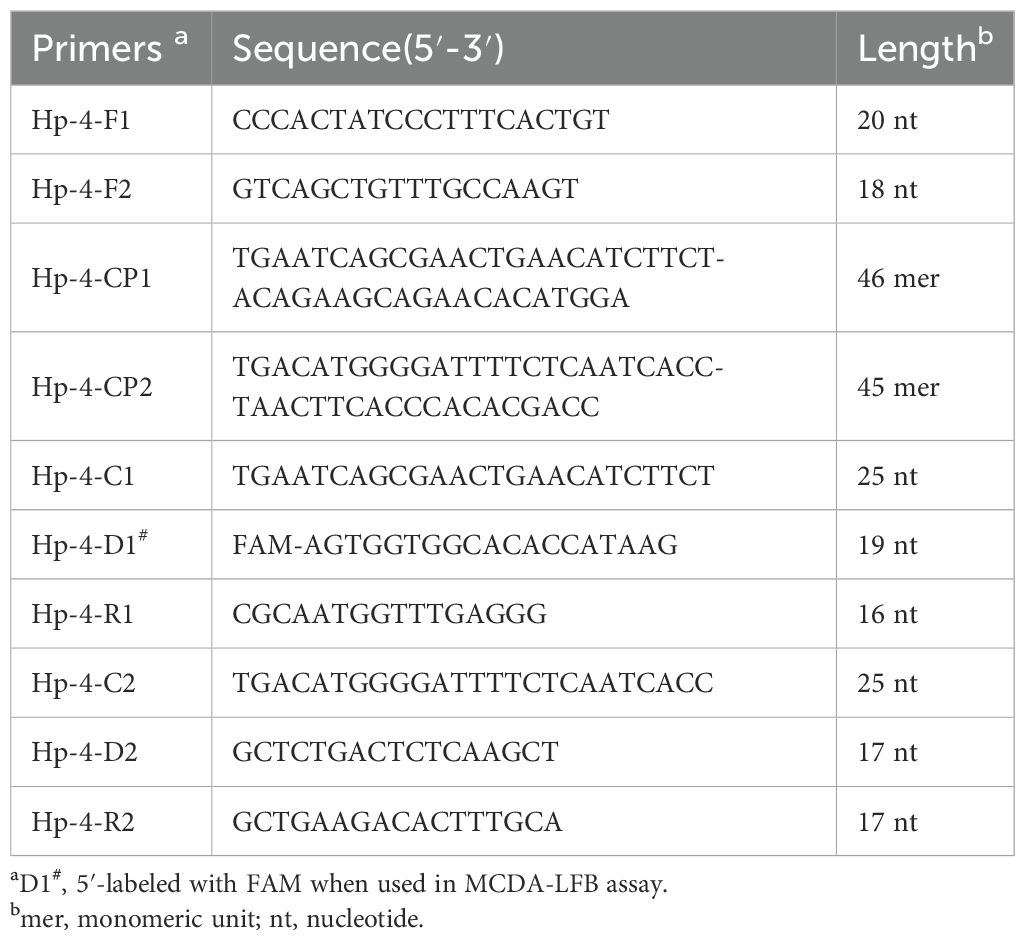

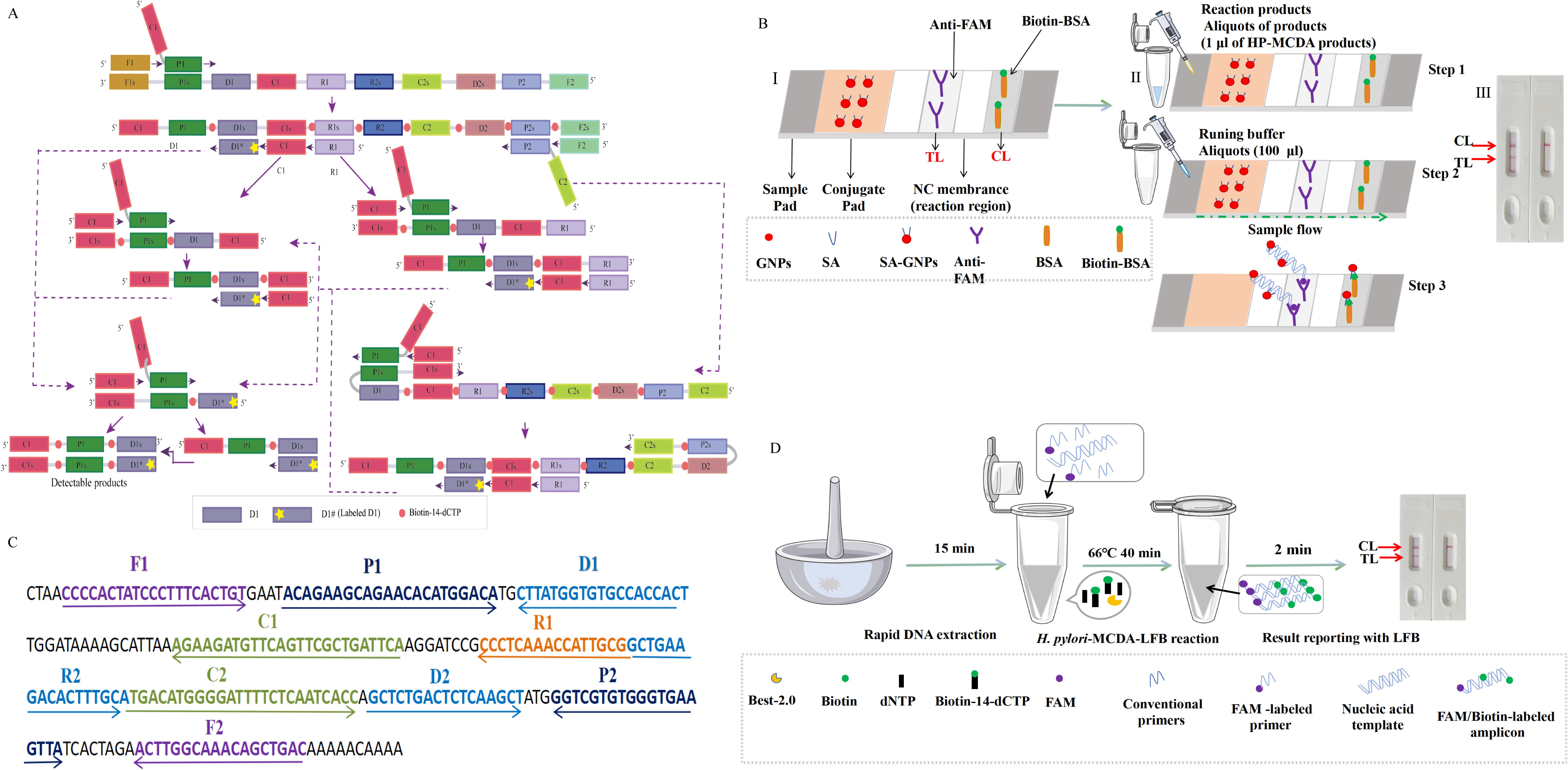

2 Materials and methods2.1 Primer designThe design of H. pylori-specific primers for MCDA reaction was performed based on the nucleotide sequence of ureB gene (accession no. CP003904) using the Primer Premier Version 5.0 software according to the principle of MCDA (Wang et al., 2015). The MCDA primers were composed of 10 primers targeting 10 distinct regions of target sequence, including a pair of cross primers (CP1 and CP2), a pair of displacement primers (F1 and F2), and three pairs of amplification primers (C1 and C2, D1 and D2, and R1 and R2). For biosensor detection, one amplification primer D1 was additionally labeled a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FAM) at the 5′ end (termed D1#). Sequences of all the primers are shown in Table 1. Details of primer sequences, locations, and modifications are shown in Figure 1C, and all the primers were synthesized and purified at HPLC purification grade by Tianyi‐Huiyuan Biotech. Co, Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

Table 1. Primers used in this study.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of HP-MCDA‐LFB assay’s principle. (A) Principle of MCDA assay with D1# and biotin‐14‐dCTP. D# of HP‐MCDA reaction was labeled with FAM at the 5′ end and of the central-MCDA reaction with digoxin. (B) The detection principle of LFB for visualization of HP‐MCDA products. I, Structure diagram of LFB. II, Principle and steps of LFB for detection of HP‐MCDA products. III, Analysis of the HP‐MCDA‐LFB results: a positive result for H. pylori strains (TL and CL appear on the detection region); a negative result (only the CL appears on the LFB). ① a positive result for Central MPXV strains (TL1, TL2, and CL appear on the detection region); ② a positive result for Central African MPXV strains (TL2 and CL appear on the detection region); and ③ negative result (only the CL appears on the LFB). (C) The sequences, positions, and modifications of the gene. The right and left arrows are sense and complementary DNA sequences, respectively, which were used in this study. (D) Workflow of the HP‐MCDA‐LFB assay. The whole assay could be completed within 1 h, including 15 min for DNA extraction, 40 min for HP-MCDA reaction, and 5 min for results reporting. LFB, lateral flow biosensor; MCDA, multiple cross displacement amplification; HP, H. pylori.

2.2 Reagents and apparatusThe universal isothermal amplification kits, biotin‐14‐dCTP, visual detection reagent (VDR), and LFB strips were obtained from HuiDeXin Biotechnology (Tianjin, China), and the article numbers are HC-300-L, HT10005, and HT10004. The DNA extraction kits were purchased from TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China, HT0600). Real-time turbidity (LA-320C) was provided by Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd (Japan).

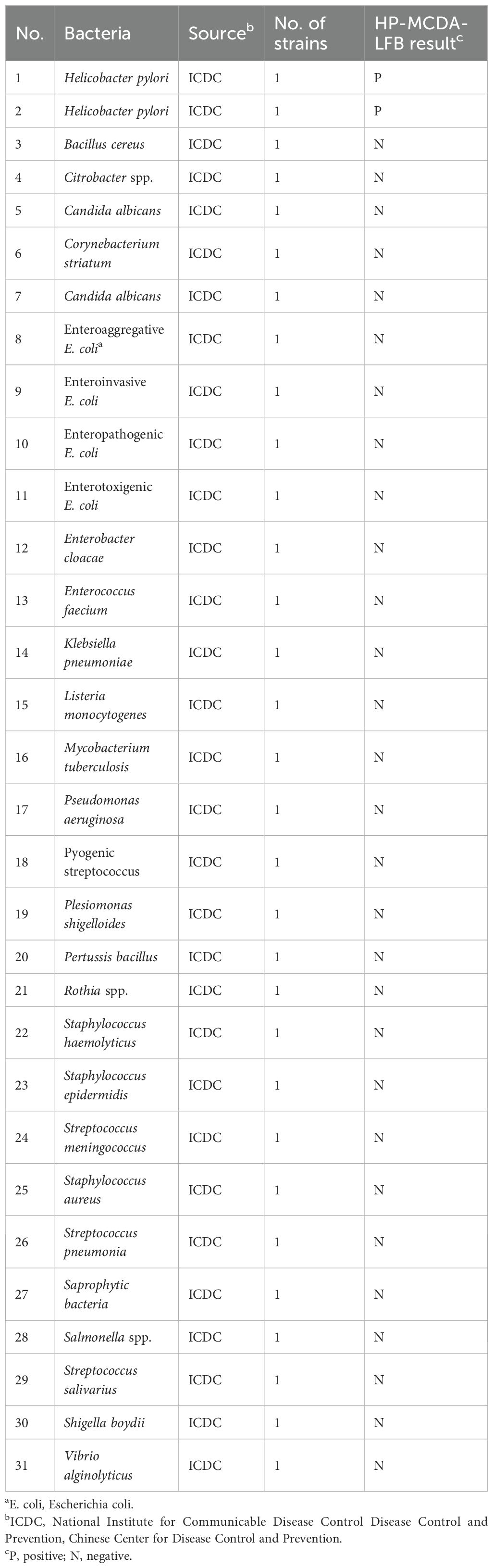

2.3 Preparation of pathogens and clinical samplesA total of 40 gastric antrum mucosa samples collected from patients admitted at the Department of Gastroenterology, Capital Institute of Pediatrics from September 2021 to March 2022 were employed in this study. A total of 17 of the 40 samples were diagnosed as H. pylori infection by the positive results of urea breath test or stool antigen combining with rapid urease test (RUT), while the remainder were considered as functional gastrointestinal disorder with an H. pylori-negative result. Clinical samples were taken from the minor curvature of the gastric antrum and one piece from the greater curvature of the gastric body (the biopsy location of the gastric antrum was within 5 cm from the pylorus opening, and the sampling location of the stomach body was within 8 cm from the cardia). Genomic DNA of the 40 clinical samples were extracted and purified using the commercially available kit (Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd.) as per the manufacturer’s instruction. The extract nucleic acid was stored at −20°C for subsequent use. In addition, 29 non-Helicobacter pathogens obtained from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were processed as the clinical samples, and the extracted genomic DNA samples were employed for the specificity analysis of the HP-MCDA-LFB (Table 2).

Table 2. Bacterial strains used in the current study.

2.4 The standard HP-MCDA reaction assayAs per the previous studies (Wang et al., 2015, 2018), the HP-MCDA reaction was conducted in a 25-µl amplification mixture, containing 0.4 µM each of displacement primer (F1 and F2), 0.8 µM each of amplification primer (C1, C2, R1, R2, D1#, and D2), 1.2 µM each of cross primer (CP1and CP2), 12.5 µl 2× reaction mixture, 1.5 µl VDR, 1 µl Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase, 1 µl DNA template from pure culture or 5 µl from clinical specimens, and moderate distilled water (DW) to a final volume of 25 µl. The MCDA reaction mixtures were incubated at 66°C for 40 min followed by 105°C for 5 min to stop the amplification. Genomic DNA of H. pylori was used as positive control, that of Listeria innocua (a resident of food, which may transiently exist in the stomach) as negative controls, and DW as blank control. The MCDA reaction results were determined according to the dynamic curve of real-time turbidity and the color change of the final reaction tube. Typically, turbidity value higher than 0.1 or a light blue color of reaction mixture indicated a positive result, while that lower than 0.1 or colorless implied a negative one.

2.5 Biosensor detection of HP-MCDA productsFor biosensor detection of the products of HP-MCDA reaction, LFB strip was utilized. In detail, an aliquot of 1 μl MCDA product was added to the sample pad region of LFB (Figure 1B, II, step 2), followed by addition of an aliquot of 100 μl running buffer (10 mM PBS, pH 7.4 with 1% Tween 20) to the same region (Figure 1B, II, step 2). After 5 min, the result was indicated by the presence or absence of red band in the NC membrane region (Figure 1B, III), with red bands occurring in both the testing line (TL) and control line (CL) as positive result and only a red band in CL as negative.

2.6 Optimization of the HP-MCDA-LFB assayThe performance of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay may be influenced by the MCDA reaction temperature, reaction time, and the volume of MCDA products for LFB detection. The optimal reaction temperature of HP-MCDA reaction was determined by performing the reactions at temperatures of 60°C–67°C at 1°C intervals for 40 min. The optimal reaction time was examined by implementing MCDA reactions for 10–40 min (with 10 min interval), respectively. The optimal volume for LFB test was evaluated by adding varied volumes (0.25 µl, 0.5 µl, 1 µl, 1.5 µl, and 2.0 µl) of HP-MCDA products to the sample region of LFB strip and reporting the result within the same period of time.

2.7 Sensitivity and specificity evaluation of the HP‐MCDA‐LFB assayTenfold serial dilution of the genomic DNA of H. pylori (600 pg μl−1 to 60 fg μl−1) was prepared to determine the analytical sensitivity and limit of detection (LoD) of the MCDA-LFB assay for H. pylori detection. In parallel, MCDA products of the serial dilutions of genomic DNA of H. pylori was visually reported with VDR. Each test was implemented with three replicates.

2.8 Specificity evaluation of the HP-MCDA-LFB assayThe specificity of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay was evaluated using genomic DNA templates from 29 bacterial pathogens. After amplified under the conditions mentioned above, the obtained products were interpreted by both VDR and LFB detection formats. Each sample was tested independently at least three times.

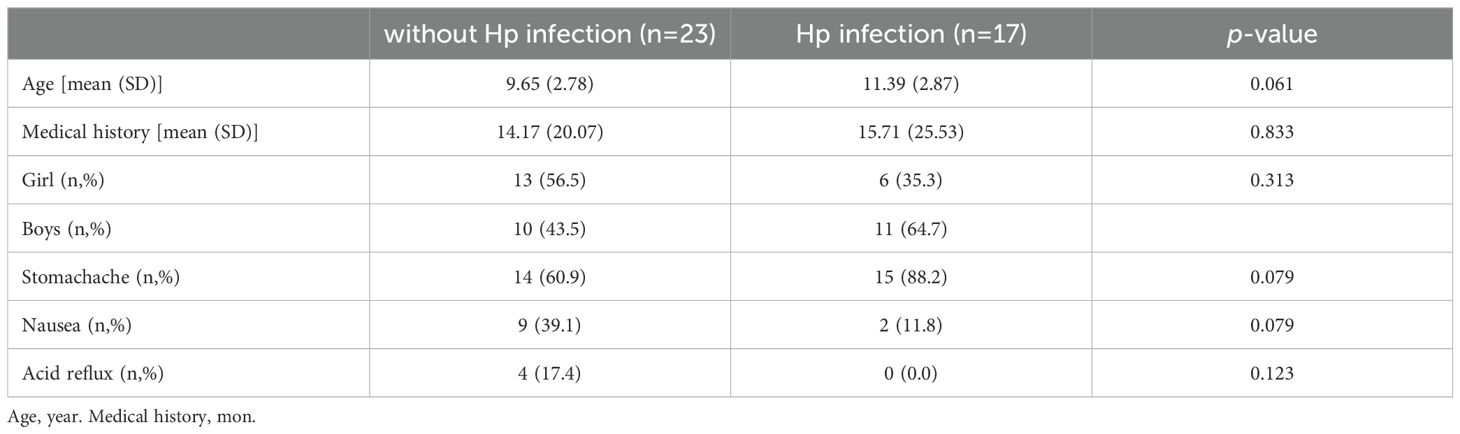

2.9 Clinical feasibility verification of the HP-MCDA-LFB assayIn order to further validate the feasibility of the HP-MCDA-LFB technology in clinical H. pylori detection, gastric antrum mucosa samples from patients suspected of H. pylori infection at Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics were collected. These samples were detected by RUT method previously, a common rapid diagnostic method of H. pylori via detecting the activity of bacterial enzyme urease. Detail information of all the samples was listed in Table 3. Genomic DNA extracted from the rest of these samples was deployed to HP-MCDA-LFB test. Results obtained through both methods were compared to confirm the clinical application potential of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics without H. pylori infection and with H. pylori infection.

3 Result3.1 Schematic illustration of the HP-MCDA-LFB assayThe principle of the MCDA-LFB method for H. pylori detection is shown in Figure 1A. Briefly, the MCDA reaction was carried out as previously described, which used only a DNA polymerase with strand-replacement activity (Bst 2.0) and a set of 10 primers specifically spanning 10 different regions of the target sequence to achieve exponential amplification of the analytes. The MCDA assay was initiated by the cross primer CP1 annealing the target sequence, then replaced by the newly synthesized strand primed with F1, leading to release of the strand primed with CP1, which was employed as templates of subsequent amplification. Within a short time, plenty of strands complementary to the primer D1# were produced, resulting in substantial double strands primed with D1# generated. Particularly, biotin-labeled cytosine deoxynucleotide (biotin-14-dCTP) was additional added in the reaction mixture, leading to biotin labeled in the amplification products. As a result, the D1# primed products contained both FAM and biotin labels and were considered as the detectable targets, which could be captured and visually inspected with LFB strips.

3.2 Principle of biosensor detection of HP-MCDA products by LFBDetails of biosensor detection of HP-MCDA products with LFB are shown in Figure 1B. The LFB strip was adapted for use by using anti-fluorophore antibodies (anti-FAM) to capture FAM-containing amplicons and using streptavidin-coated dyed (crimson red) polymer nanoparticles (SA-GNPs) to bind biotin-containing amplicons for readout visualization. As previously described (Wang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2023), SA-GNPs were deposited on the conjugate pad of the LFB strip; anti-FAM and biotinylated bovine serum albumin (biotin-BSA) were on the TL and CL regions of NC membrane, respectively. If the target analyte was present, the double-labeled (FAM and biotin-containing) products will flow down the strip and eventually captured by anti-FAM and visualized via SA-GNPs with red bands occurring in both TL and CL regions, while the absence of target amplicons only appeared as red band only in CL region due to the interaction between biotin-BSA and SA-GNPs.

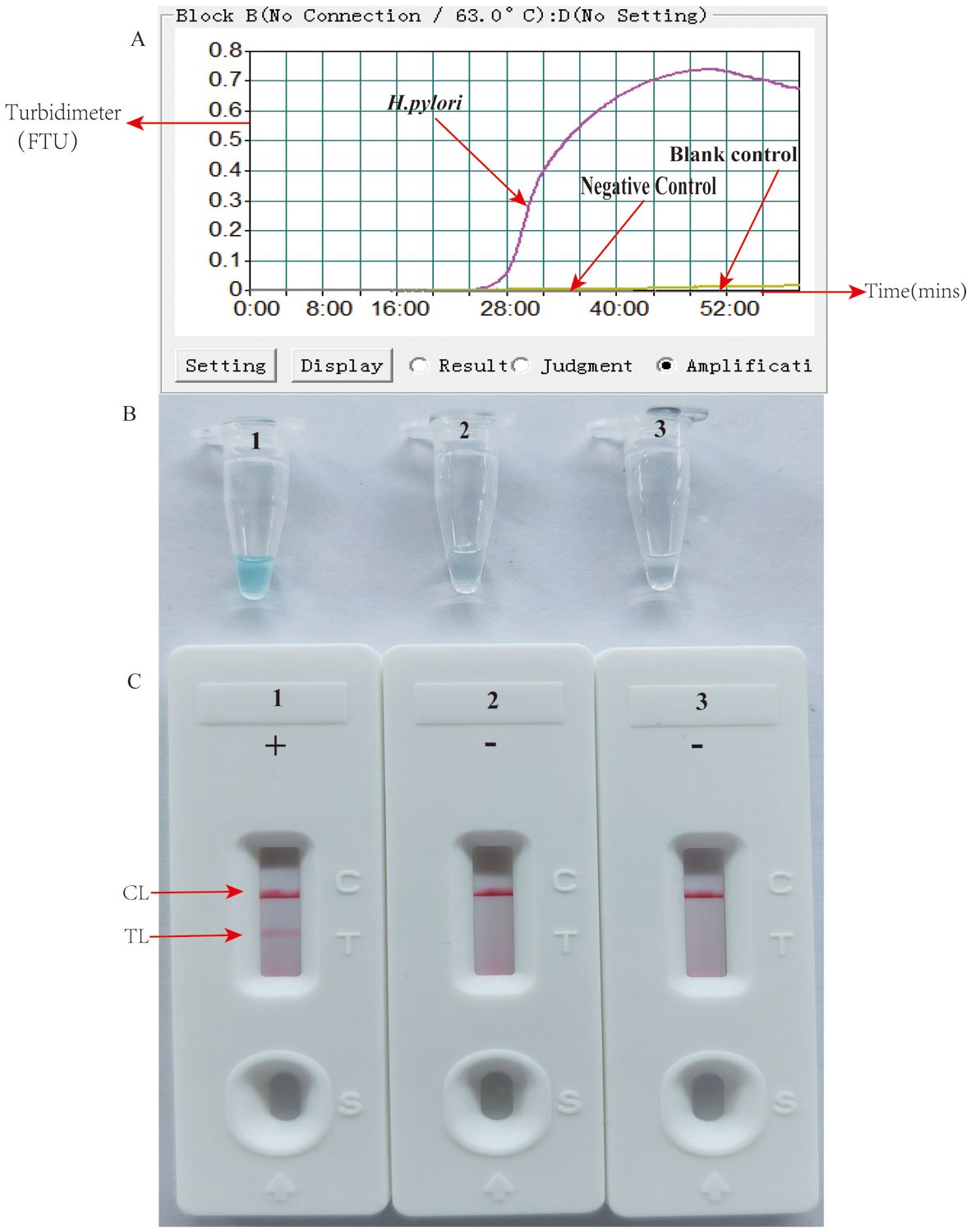

3.3 Effectiveness confirmation of the primers for HP-MCDA-LFB assayPrimer set feasibility for the HP-MCDA-LFB assay was determined by performing H. pylori MCDA reaction and reporting the results with LFB strip along with real-time turbidimeter and VDR. As shown in Figure 2A, by real-time turbidimeter, it was observed that only the positive control reaction reached a turbidity value higher than 0.1 within a short time, while the negative and blank controls all displayed blunted curves within the whole incubation time; with VDR, the tube of positive control mixture showed light green in color while that of negative and blank controls were colorless (Figure 2B); on the LFB strips, positive control reaction products induced two red bands in the TL and CL region, simultaneously, while the others only exhibited a red band in the CL region (Figure 2C). Data from the three detection formats demonstrated the effectiveness of the selected primer and its feasibility in the HP-MCDA-LFB assay for H. pylori detection.

Figure 2. Detection and confirmation of HP-MCDA-LFB assay for H. pylori detection. Amplification products were analyzed by measuring turbidity in real time (A). The ordinate represents the turbidimeter (FTU), the abscissa axis is reaction time (min). VDR (B) and LFB (C). Tube 1/biosensor 1, positive amplification of H. pylori; tube 2/biosensor 2, negative control of Listeria innocua; tube 3/biosensor 3, blank control of double distilled water (DW).

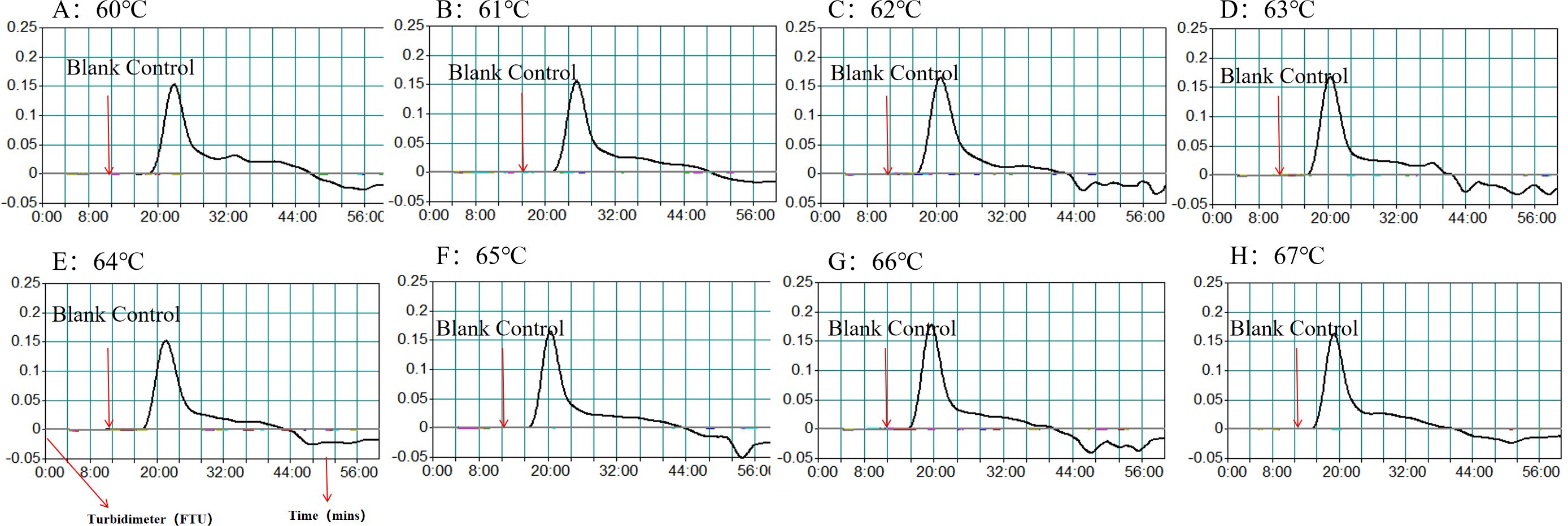

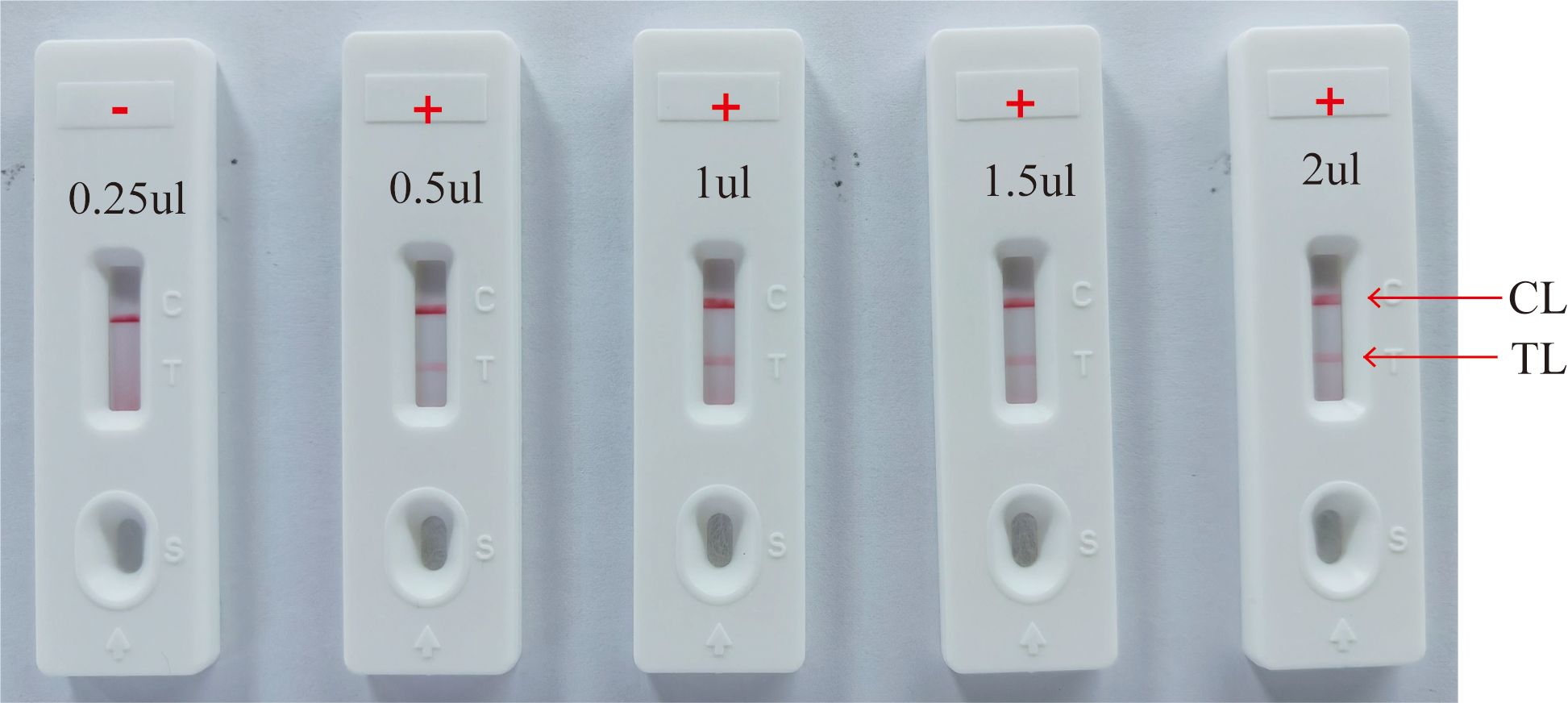

3.4 Optimal reaction conditions of HP-MCDA-LFB assayEfficiency of the HP-MCDA assay at temperatures 60°C–67°C were exhibited in Figure 3. According to the kinetic curves, it was observed that reactions at 66°C allowed for the most abundant products and the fastest speed to reach a turbidity of 0.1. Thus, 66°C was considered as the optimal reaction temperature of HP-MCDA reaction. Additionally, after amplifying LoD level of genomic DNA of H. pylori (60 fg) at 66°C for 10 min, 20 min, 30 min, and 40 min, respectively, the products were detected in formats of VDR and LFB. As shown in Figure 4, the shortest time required to detect LoD levels of genomic DNA of H. pylori was 40 min. As a result, the whole detection procedure for HP diagnosis, including rapid template extraction (15 min), MCDA reaction (40 min), and result reporting using LFB (5 min), could be finished within 1 h (Figure 1D). Then, the optimal volume of products for LFB detection was determined by loading 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 µl of amplification products to the sample pad region of LFB strip, respectively. As displayed in Figure 5, the LFB strips loading 0.5–2 µl of product all showed two red bands at CL and TL regions within 5 min, while the one with 0.25 μl products showed only one red band at CL. Considering the potential of aerosol pollution, 0.5 μl of HP-MCDA product was accepted for LBF detection. In summary, the optimal reaction conditions, including a reaction temperature of 66°C, a reaction time of 40 min, and a product loading volume of 0.5 μl, were employed for the subsequent analysis.

Figure 3. Optimization of amplification temperature for MCDA assay. The standard MCDA reactions for detecting H. pylori was monitored by measuring turbidity in real-time manner. The threshold value was 0.1, and a turbidity value > 0.1 was considered a positive result. Eight kinetic graphs (A–H) were obtained at various temperatures (60°C–67°C, 1°C intervals) with target pathogens DNA at the level of 60 fg µl−1.

Figure 4. Optimization of reaction time for HP-MCDA-LFB assay. Four different reaction times (10 min, 20 min, 30 min, and 40 min) were tested and compared using H. pylori pathogens at a concentration of 60 fg at the optimal amplification temperature (66°C).

Figure 5. Optimization of amplicon content for LFB detection. Different volumes (0.25 µl, 0.5 µl, 1 µl, 1.5 µl, and 2.0 µl) of HP-MCDA amplicon were extracted and titrated into LFBs to verify the sufficient content for effective detection by LFB assay; “+” positive; “−” negative.

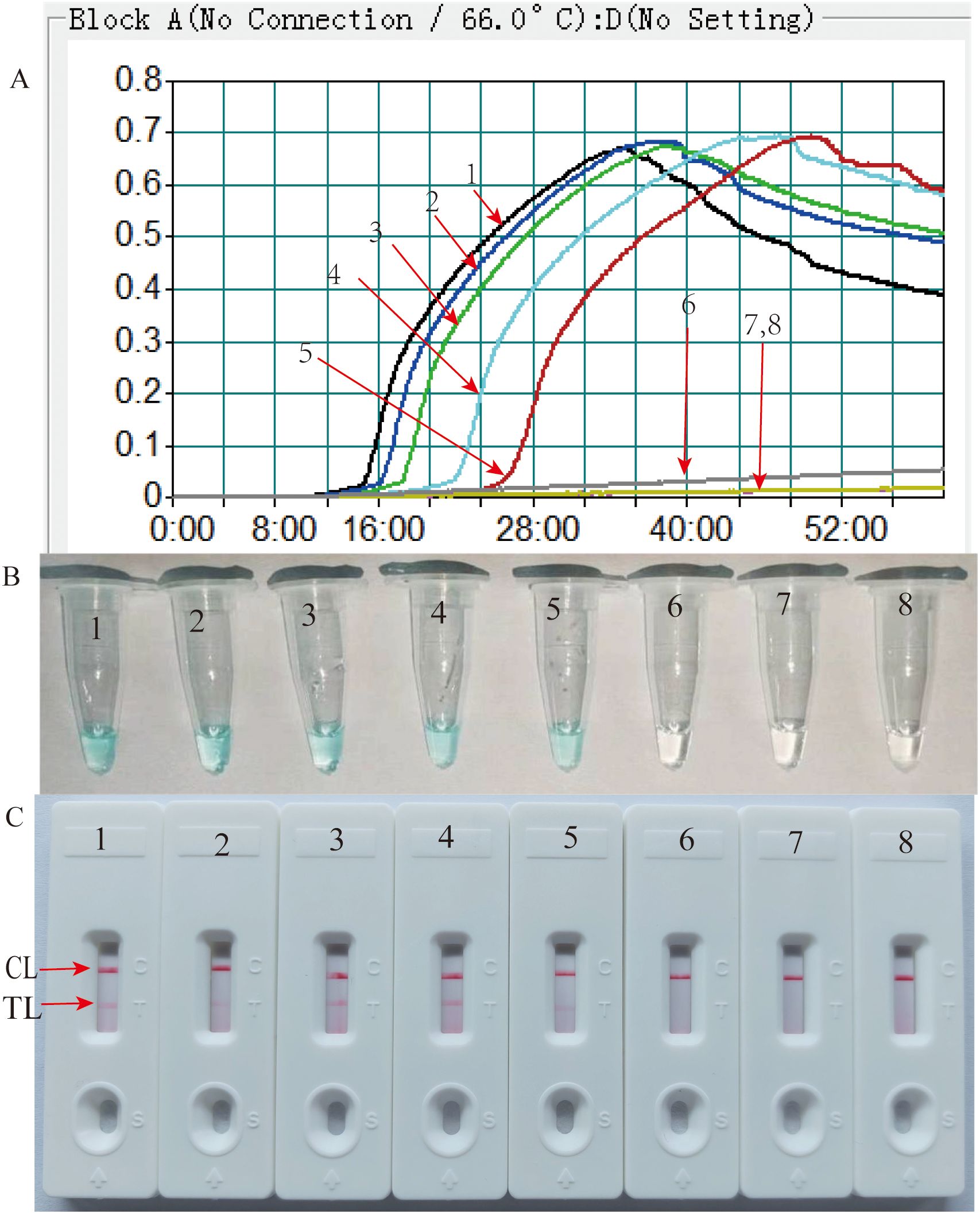

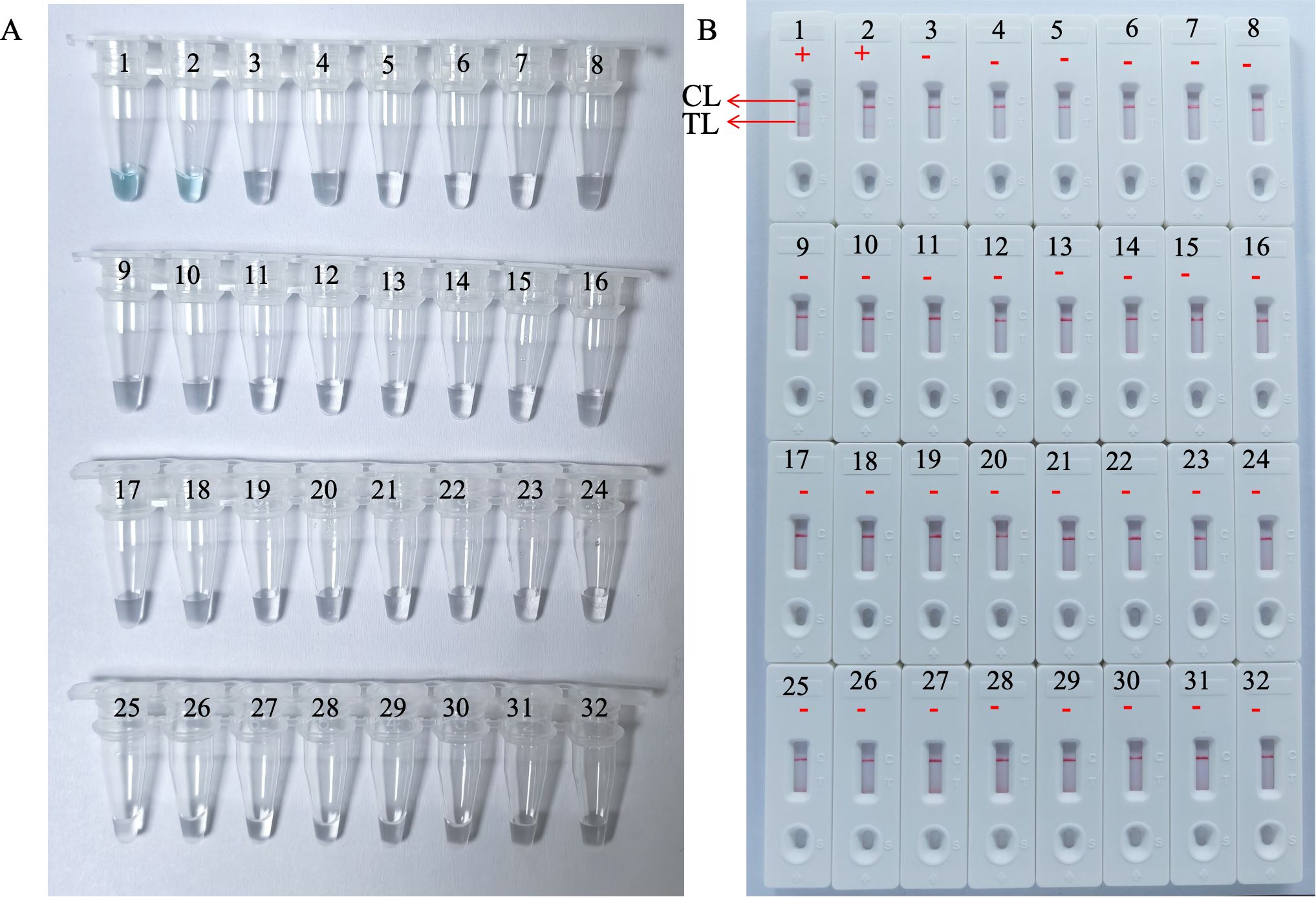

3.5 Sensitivity and specificity of the HP-MCDA-LFB assayAnalytical sensitivity of the HP-MCDA-LFB was determined using the serial dilutions of genomic DNA templates of H. pylori. After testing each titer with three replicates, it was revealed that the detection limit of HP-MCDA-LFB assay was 60 fg μl−1, which was demonstrated by LFB strip exhibiting two red bands in the TL and CL regions when loaded with products from templates not less than 60 fg (Figure 6C). Similarly, only the reaction with at least 60 fg templates displayed a sharp curve by real-time turbidimeter (Figure 6A) and showed light green in color (Figure 6B), revealing an identical LoD level to HP-MCDA-LFB assay. For the purpose of specificity analysis, 29 non-Helicobacter pathogens were detected. As envisaged, all the LFB strips loaded with MCDA products from non-Helicobacter pathogens showed red band only in the CL regions, while the positive control displayed two red bands in the TL and CL regions of LFB strip (Figure 7), indicating a 100% specificity of HP-MCDA-LFB assay in H. pylori detection.

Figure 6. Analytical sensitivity of HP-MCDA-LFB assay. Serial dilutions (600 pg µl−1, 60 pg µl−1, 6 pg µl−1, 600 fg µl−1, 60 fg µl−1, and 6 fg µl−1) of target templates were subjected to conventional MCDA reactions, and the results were monitored by real-time turbidity (A), VDR (B), and LFB (C) formats. Biosensors A1–A7 (tubes 1–7 and signals C1–C7). A1–A7 shows different concentrations of H. pylori genomic templates; blank line is 600 pg µl−1, blue line is 60 pg µl−1, green line is 6 pg µl−1, wathet blue line is 600 fg µl−1, brown line is 60 fg µl−1, and yellow line is 6 fg µl−1), respectively; biosensors A8 (Tube B 8 and Signal C 8) indicated negative control (DW).

Figure 7. Analytical specificity of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay. The specificity of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay was evaluated using 29 non-Helicobacter pathogens. The amplification products was interpreted by VDR method (A) and LFB platform (B). Tubes/LFBs 1–2 represented H. pylori pathogens, and 3–31 showed 29 non‐H. pylori pathogens, and the details are shown in Table 3. CL, control line; LFB, lateral flow biosensor; MCDA, multiple cross displacement amplification; HP, H. pylori; TL, test line.

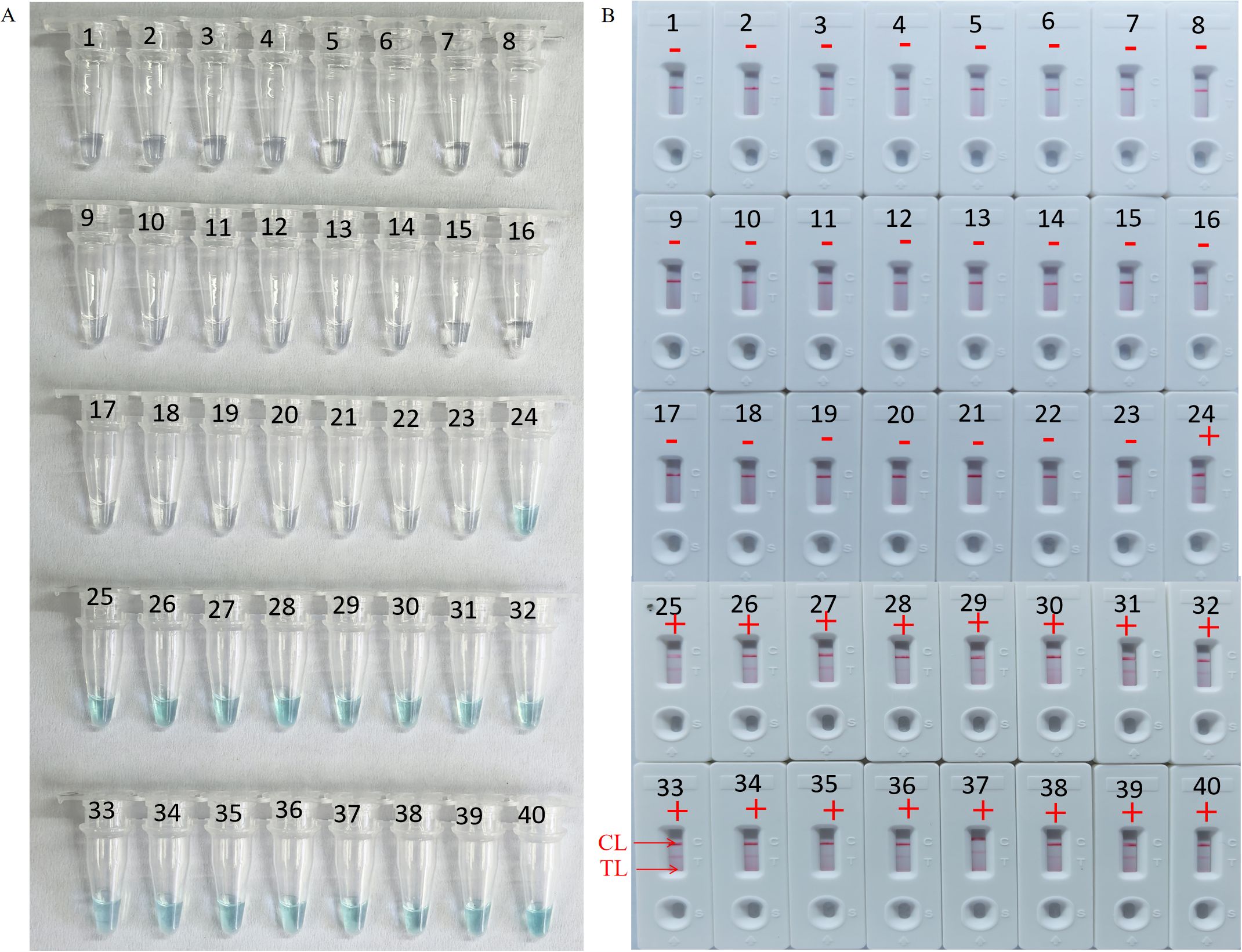

3.6 Feasibility assessment of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay in clinical samplesTo further validate the feasibility of HP-MCDA-LFB as a diagnostic tool for H. pylori in clinical settings, we examined 20 endoscopically suspected of H. pylori infected gastric sinus tissues and 20 gastric sinuses with normal endoscopic mucosa using both HP-MCDA-LFB and RUT. As a result, 17 H. pylori-positive samples diagnosed by RUT were tested positive for H. pylori by HP-MCDA-LFB, and the 23 URT H. pylori-negative samples were negative in the HP-MCDA-LFB assay as well (Figure 8), demonstrating high degree of agreement between the two methods. The results implied that the HP-MCDA-LFB method was an accurate and sensitive screening tool for H. pylori infection and indicated great potential to be widely used in clinical laboratories and basic research.

Figure 8. Clinical feasibility assessment of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay. The amplification products was interpreted by VDR method (A) and LFB platform (B). Tubes 1–23 using VDR method represented clinical samples that were not considered H. pylori infection by rapid urease tests, Tubes 24–40 using VDR method represented clinical samples that were considered H. pylori infection by rapid urease tests. B1–23 using LFBs method represented clinical samples that were not considered H. pylori infection, B24–40 using LFBs method represented clinical samples that were considered H. pylori infection. CL, positive control; TL, negative control; “+” positive; “−” negative.

4 DiscussionH. pylori represents one of the most widespread bacterial infections all over the world, affecting half of the world’s population with high morbidity and mortality (Malfertheiner et al., 2017). Although the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection has declined in recent years with living standards improved, reported morbidity and mortality associated with gastric cancer in adults remain high (Hooi et al., 2017). In addition, H. pylori has been reported increasingly resistant to clarithromycin and metronidazole, which were essential for the eradication of H. pylori (Zheng et al., 2022). The increasing antibiotic resistance rate has given rise to treatment failure, further aggravating the global burden of H. pylori-related gastric complications. Accurate and early diagnosis of H. pylori infection paved a critical way toward successful eradication of H. pylori and alleviating the progress of antimicrobial resistance.

Because of population growth and because of reinfection and recrudescence due to unsuccessful eradication, H. pylori infection rates persisted or even increased over the past three decades in the world (Hu et al., 2017). The clinically commonly used techniques for the detection of H. pylori to diagnose H. pylori-induced complications and evaluate the outcomes of H. pylori eradication included urea breath test (UBT), RUT, and bacterial culture. UBT is the most widely recommended method for H. pylori detection and for eradication effort assessment after antibiotic therapy (Chen et al., 2023). Due to the noninvasive property, however, the result was vulnerable to the drug used and endogenous carbon dioxide production. Therefore, a simple, easy-to-operate, rapid, and sensitive test device remains highly desirable for primary care providers to detect H. pylori infection in resource-limited areas.

The newly devised HP-MCDA-LFB assay, an isothermal nucleic acid detection platform targeting the critical virulence factor coding gene ureB (Liu et al., 2023, 2023; Tanahashi et al., 2000), exhibited excellent performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity and was promising in the rapid, simple, and accurate diagnosis of H. pylori infection. Our findings suggest that the newly designed Hp-MCDA-LFB assay has high sensitivity and specificity and is well suited for implementation in primary care settings.

The newly developed HP-MCDA-LFB assay is a user-friendly, simple, and portable diagnostic tool for H. pylori detection. The HP-MCDA-LFB assay utilized MCDA technique to amplify target sequences and LFB for results indication. MCDA has been extensively deployed to detect nucleic acid of various pathogens due to the advantages of instrument-free, high amplification efficiency, and ultra-accuracy. Typically, the MCDA assay could achieve exponential increase in target analytes at a constant temperature (60°C–67°C) for 30–40 min using simple equipment such as metal baths, water baths, or hot water cups. In addition, the nanoparticle-based LFB allows for intuitive and objective interpretation of amplification results without expensive and complex laboratory conditions. Of note, the LFB detection of target nucleic acid in this study required only one labeled primer along with biotin-14-dCTP rather than two labeled primers, which lowered the design difficulty and cost (Chen et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2016, 2015; Zhou et al., 2023). The entire detection process, including rapid sample processing (15 min), MCDA reaction (40 min), and LFB detection (within 5 min), can be completed within 1 h. The fluorescence detection method in this study does not rely on any PCR system, but on a simple blue light device. In addition, the MCDA reaction does not include multiple denaturation and annealing cycles, which avoids the need for complex and expensive PCR equipment. Meanwhile, the cost of one MCDA-LBF reaction was less than $10 (Wang et al., 2017, 2015, 2016). Hence, the HP-MCDA-LFB assay is a simple, rapid, user-friendly, and cost-effective method that had great potential in resource-limited areas for the diagnosis of H. pylori infections.

The HP-MCDA-LFB assay demonstrated excellent performance in the detection of H. pylori. Prior to detection ability analysis, related parameters, including reaction temperature and time, and detection volume, were determined in order to achieve enhanced performance and less aerosol pollution. As a result, the optimal reaction conditions were examined as reacting at 66°C for 40 min with a volume of 0.5 µl products for LFB detection. Under the optimal conditions, the HP-MCDA-LFB assay was able to detect low to 60 fg (~56 copies) genomic DNA of H. pylori, which was more sensitive than the loop-mediated isothermal amplification-lateral flow dipstick (LAMP-LFD) method and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Liu et al., 2023), but less sensitive than the CRISPR-based detection platform (Dai et al., 2022). It was supposed that the detection method itself and/or the detection targets resulted in difference in detection sensitivity. Thus, further comparison and development need to be implemented for better diagnostic efficiency. The result of specificity analysis of the HP-MCDA-LFB method displayed no cross-reaction of this method with non-Helicobacter pathogens, indicating the reliability of HP-MCDA-LFB for H. pylori detection. In addition, the MCDA-LFB assay excels in detecting clinical H. pylori infection. In our investigation, the assay accurately identified H. pylori infection in 17 tissue mucosa-extracted DNA samples identified as having H. pylori infection. Meanwhile, it correctly excluded the presence of H. pylori in 23 tissue mucosa samples not caused by H. pylori infection. Consistent results with those from the combined RUT diagnostic approach emphasize the reliability of the HP-MCDA-LFB assay in clinical H. pylori detection.

Overall, the HP-MCDA-LFB demonstrates remarkable sensitivity and specificity, enabling visual detection of H. pylori infection with basic equipment. It is capable of detecting as little as 60 fg (~56 copies) genomic DNA of H. pylori with 100% specificity for clinical samples. Given its simplicity, sensitivity, and specificity, the HP-MCDA-FRT assay has great potential as a powerful tool for H. pylori detection in the primary care setting.

Several drawbacks yet to be addressed included the following: (1) samples for clinical validation in this study just involved the gastric sinus tissue, thus more types of samples associated with H. pylori infection are yet to be detected such as stool and saliva, which could be accessed noninvasively and more favored by the patients; (2) the LFB detection step in this study required opening the reaction tube, which increases the risk of carrying contamination and the possibility of false-positive result, thus methods integrating amplification and detection into one step are yet to be developed; and (3) the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state of H. pylori in water reservoirs remains a high risk factor of public health, thus confirmation of the effectiveness of the new method in water reservoirs will be highly appreciated.

5 ConclusionIn summary, we combined isothermal MCDA with nanoparticle-based LFB to establish an HP-MCDA-LFB diagnostic method for H. pylori detection. The analyzed data showed that the HP-MCDA-LFB method is a user-friendly, rapid, sensitive, and specific method for diagnosing H. pylori infections and can be applied in the clinical setting. The HP-MCDA-LFB assay can be performed within 1 h without the need for complex instruments and skilled technicians. Therefore, the HP-MCDA-LFB test developed in this study is an effective tool for the rapid and reliable diagnosis of H. pylori infection in both centralized laboratory and rural areas.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Human Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital Capital Institute. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributionsYC: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XH: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XLH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FX: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NJ: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Clinical and Basic Integration Project of Capital Institute of Pediatrics (Grant No. LCPY-2021-14).

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the professors in Experimental Research Center, Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ReferencesAtkinson, N. S., Braden, B. (2016). Helicobacter pylori infection: diagnostic strategies in primary diagnosis and after therapy. Dig Dis. Sci. 61, 19–24. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3877-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bogaerts, P., Hamels, S., de Mendonca, R., Huang, T. D., Roisin, S., Remacle, J., et al. (2013). Analytical validation of a novel high multiplexing real-time PCR array for the identification of key pathogens causative of bacterial ventilator-associated pneumonia and their associated resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 340–347. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks392

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cao, Q., Liang, S., Wang, L., Cao, J., Liu, M., Li, S., et al. (2021). A rapid detection of haemophilus influenzae using multiple cross displacement amplification linked with nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 721547. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.721547

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, X., Yuan, W., Zhou, Q., Tan, Y., Wang, R., Dong, S. (2022). Sensitive and visual identification of Chlamydia trachomatis using multiple cross displacement amplification integrated with a gold nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor for point-of-care use. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 949514. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.949514

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, Y., Yang, C., You, N., Zhang, J. (2023). Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and glycated hemoglobin: a cohort study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1196338. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1196338

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chey, W. D., Leontiadis, G. I., Howden, C. W., Moss, S. F. (2017). ACG clinical guideline: treatment of helicobacter pylori infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112, 212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chey, W. D., Wong, B. C. (2007). American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102, 1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dai, B., Xiang, A., Qu, D., Chen, G., Wang, L., Wang, W., et al. (2022). Rapid and sensitive assay of helicobacter pylori with one-tube RPA-CRISPR/Cas12 by portable array detector for visible analysis of thermostatic nucleic acid amplification. Front. Microbiol. 13, 858247. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.858247

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Gingras, B. A., Maggiore, J. A. (2020). Performance of a new molecular assay for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens. Access Microbiol. 2, acmi000160. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000160

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hooi, J. K. Y., Lai, W. Y., Ng, W. K., Suen, M. M. Y., Underwood, F. E., Tanyingoh, D., et al. (2017). Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 153, 420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hu, Y., Wan, J. H., Li, X. Y., Zhu, Y., Graham, D. Y., Lu, N. H. (2017). Systematic review with meta-analysis: the global recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 46, 773–779. doi: 10.1111/apt.2017.46.issue-9

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hunt, R. H., Xiao, S. D., Megraud, F., Leon-Barua, R., Bazzoli, F., van der Merwe, S., et al. (2011). Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. J. Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 20, 299–304.

留言 (0)