Primary osteosarcoma of the breast (POB) is a rare form of extraskeletal osteosarcoma originating from soft tissue. Its incidence is less than 1% among malignant breast tumors, accounting for approximately 12.5% of breast sarcomas (1–3). The exact mechanism of POB development is still unclear. Studies have shown that it may arise from neoplastic transformations of prior breast lesions such as fibroadenomas, phyllodes tumors, intraductal papillomas, and from totipotent mesenchymal cells in the breast stroma (4, 5). One possible mechanism is that, under the stimulation of radiotherapy, chronic lymphedema, trauma, or other stimuli, epithelial cells undergo mesenchymal transformation, or ossification, and further malignant transformation into osteosarcoma (6). Compared with breast cancer, POB carries a poorer prognosis, with early tumor recurrence tending to be hematogenous rather than lymphatic and most commonly metastasizing to the lungs (1, 7, 8). Presently, most reports of POB are individual cases, and cases diagnosed during lactation have not been reported. Here, we present the case of a 40-year-old lactating female diagnosed with POB of the right breast. We report the clinicopathological manifestations in this patient and discuss its diagnosis and treatment within the context of a review of relevant literature.

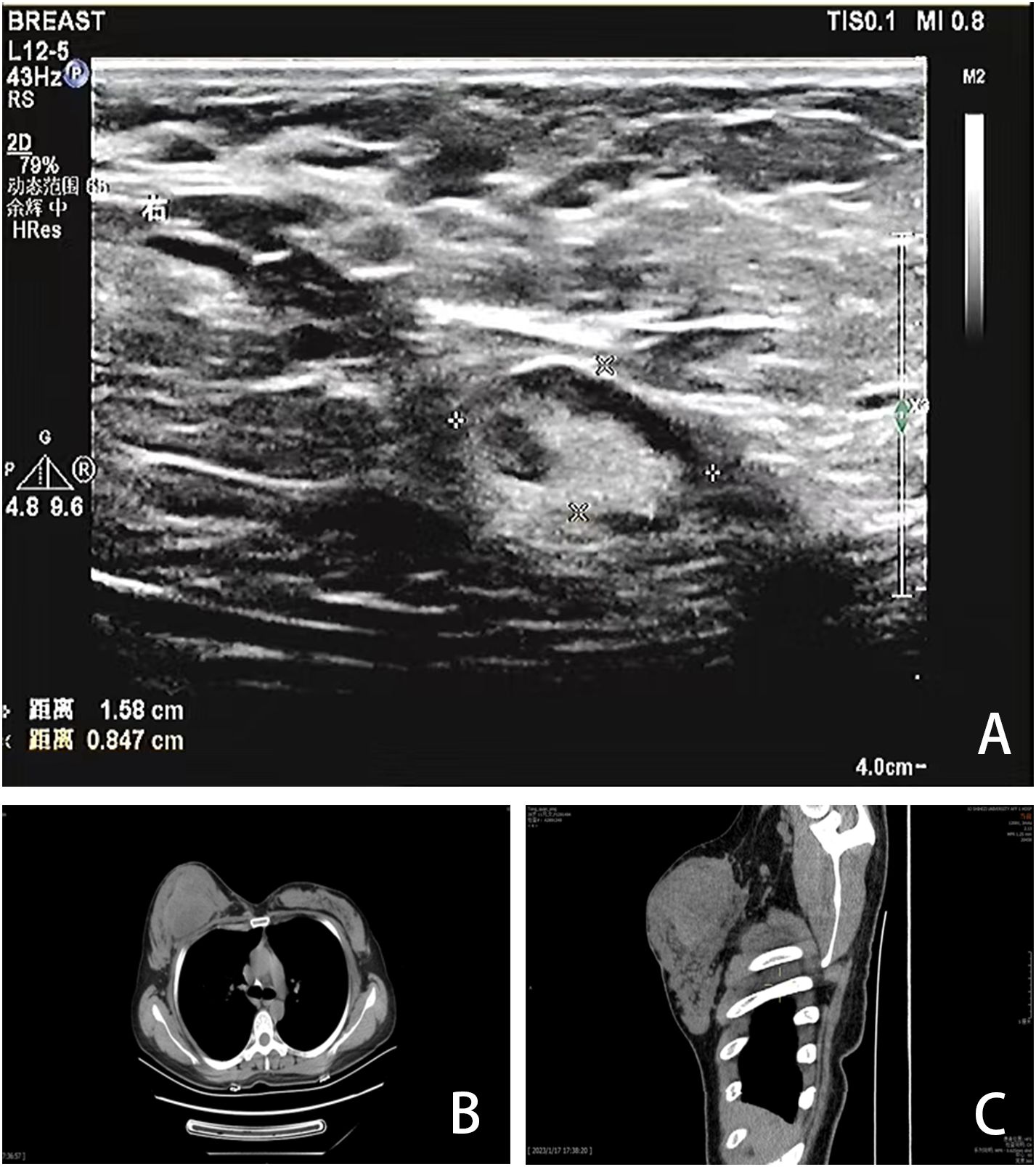

2 Case reportA 40-year-old Chinese woman, who had been breastfeeding for four months, sought medical attention due to a lump in her right breast. She did not experience any symptoms such as localized pain, skin redness, bleeding, or leakage. She was previously in good health, with no family history of genetic diseases or breast-related diseases and had never undergone breast ultrasound or mammography. She had been pregnant three times and breastfed three healthy children. Upon admission, a physical examination revealed symmetrical thoracic cage and bilateral breasts, with no redness or superficial varicose veins on the surface of the skin, no nipple inversion, no “dimple sign”, no “orange peel-like change”, and a 10×10cm mass in the right breast areola area with high tension, hard texture, and slightly higher skin temperature. Initially seeking care at a community hospital that only provides general practitioners with primary care, a color Doppler ultrasound (CDUS) revealed a mixed echo area in the right breast measuring 60×33 mm, suggesting inflammatory changes. She was diagnosed with a breast abscess and prescribed with oral ceftriaxone for eight days following three days of oral penicillin treatment. However, there was no improvement. A month later, she was referred to the First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University. The CDUS examination revealed rough echoes in both breasts, with an inhomogeneous mixed echo area approximately 9.7×6.0×10 cm in size in the right breast, exhibiting an unclear boundary and an irregular shape (Figure 1A). Color Doppler flow imaging (CDFI) showed blood flow signals therein. The contralateral breast showed no significant space-occupying lesions. Based on these imaging data, the lesions were initially considered to be inflammatory by the imaging physicians at the First Affiliated Hospital. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a round mass shadow with patchy low-density patches and septa in the right breast measuring approximately 7.1×5.2 cm in diameter. Apart from the mediastinum and significant arteries, no swollen lymph nodes were observed (Figures 1B, C). Under the guidance of ultrasound, the abscess was punctured and the sample was cultured for bacteria, which showed a negative result. Considering the malignant tumor, the surgeon opted for breast lesion resection and pathological biopsy to remove the lesion and simultaneously clarify the diagnosis.

Figure 1. Imaging findings. (A) CDUS showed a heterogeneous mixed echo area of 9.7×6.0×10cm in the right breast. (B, C) CT showed a round mass in the right breast with patchy low-density patches and septations, with a diameter of 7.1×5.2cm.

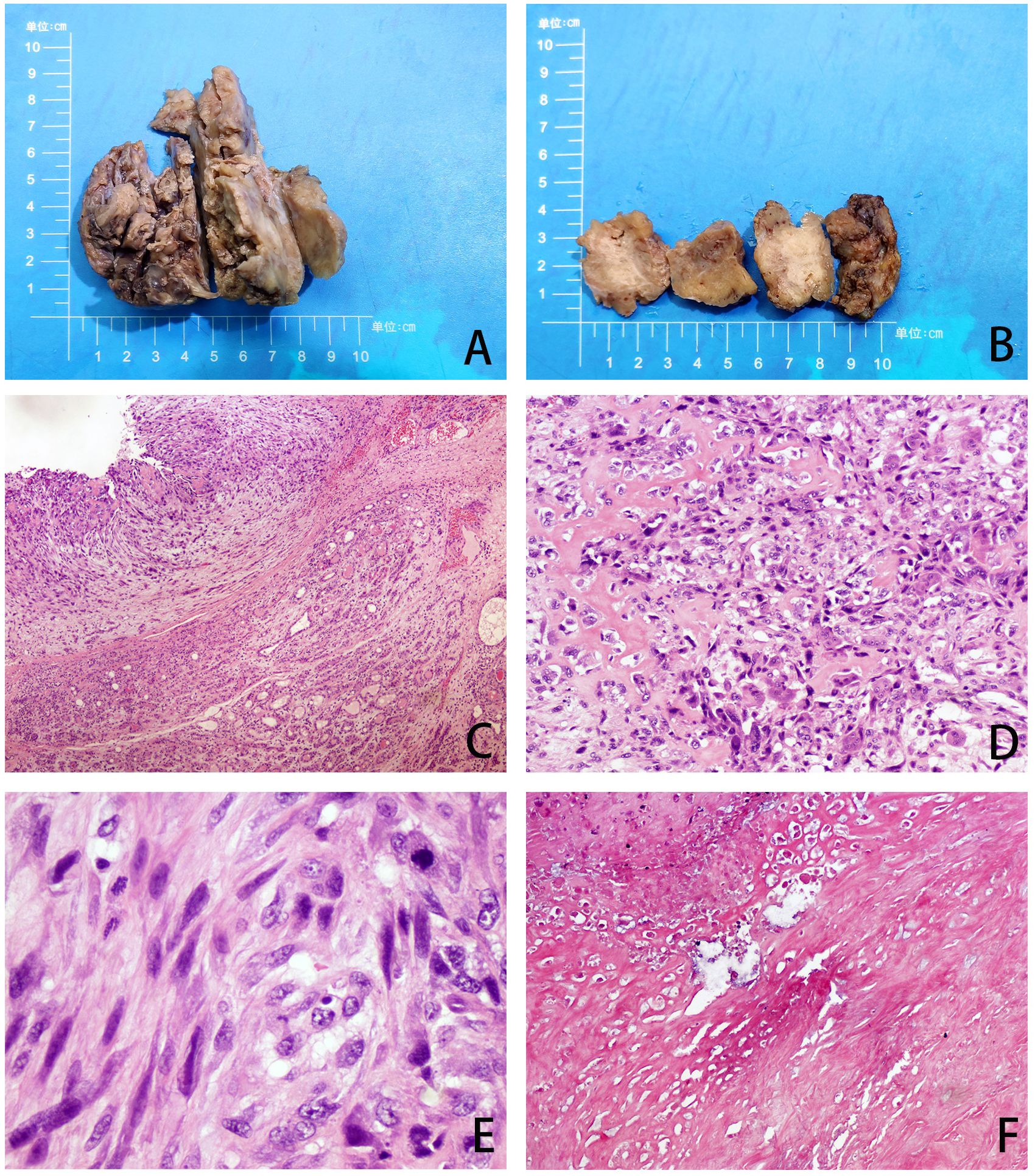

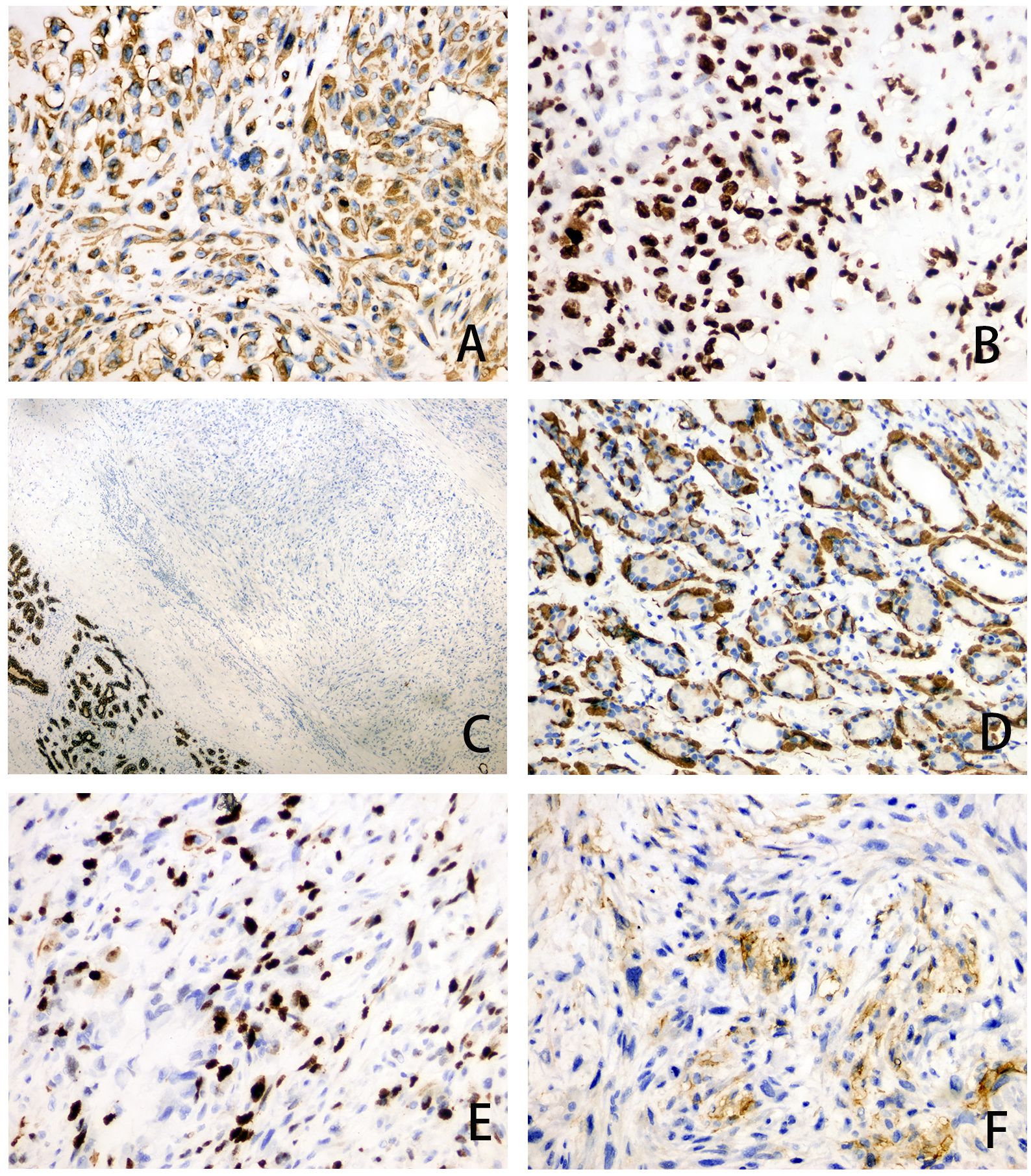

The patient underwent excision of the inflammatory necrotic tissue, resulting in the removal of approximately 8.4×7.5×3.5 cm of non-neoplastic broken tissue (Figure 2A). The lesion tissue was partly cystic and partly solid, with a slightly dark red inner cyst wall and surrounding nodules measuring 4.5×3.3×3.2 cm. The nodular section was gray and grayish-yellow, and the texture was hard. Some areas exhibited lustrous surfaces and a mucous-like consistency (Figure 2B). The tissue excised from the right breast was subjected to histological examination. Microscopically, the breast tissue showed lobular hyperplastic changes with adjacent vesicles and sarcomatoid changes in the cyst wall. A clear demarcation between tumor and hyperplastic areas was evident (Figure 2C). The osteoid matrix, giant cells, and osteogenesis were observed in some areas of the tumor. Tumor cells displayed spindle-shaped or polygonal morphology with atypia (Figure 2D). High-power magnification imaging showed spindle cells arranged in bundles, with some exhibiting swirling or random distribution. Cells displayed sparse cytoplasm, unclear boundaries, deep nuclear staining, and round, oval, or short spindle shapes. Vacuolar changes were noted in the spindle cell cytoplasm, along with aberrant pleomorphic tumor cell mitosis and prevalent pathological mitosis (Figure 2E). Extensive necrosis was observed in peripheral areas (Figure 2F). This pathological form must be differentiated from metaplastic breast carcinoma by osteomatrix differentiation. So, we performed a biopsy of all tumor tissue, but did not find any epithelial component on the histomorphology. We performed further an immunohistochemical examination, revealing that the tumor area was positive for vimentin and SATB2 (Figures 3A, B), while CK5/6 and SMA were negative (Figures 3C, D). The Ki-67 immunohistochemistry revealed a proliferation index of approximately 55% in breast adenosis adjacent to osteosarcoma. CD99 immunohistochemical staining showed scattered and weakly positive staining (Figures 3E, F). Based on the morphological and immunohistochemical findings, no epithelial component was found and we excluded metaplastic breast carcinomas with osteomatrix differentiation. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with POB. POB is not suitable for breast cancer staging systems because of its sarcomatoid nature. Following the staging classification for osteosarcoma established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), the patient was in stages T2N0M0. The patient was in stage G3 according to the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Organization (FNCLCC) staging system for pathological grading, and the patient was in stage IIA according to the combined AJCC and FNCLCC staging system.

Figure 2. (A, B) Gross observation of lesion resection specimens. (C) The tumor and adenoma areas of breast tissue were clearly demarcated (H&E, ×40). (D) The tumor is spindle-shaped and shows an obvious osteoid matrix, giant cells, and osteogenesi. (H&E, ×100). (E) Under high magnification, pathological mitotic images are easily visible (H&E, ×400). (F) Extensive necrosis (H&E, ×40).

Figure 3. (A–F) Immunohistochemical staining of tumor area for Vimentin (magnification, ×200), SATB2 (magnification, ×200), CK5/6 (magnification, ×40), SMA (magnification, ×200), Ki-67 (magnification, ×200) and CD99 (magnification, ×200).

The patient underwent modified radical mastectomy on the right breast after diagnosis of breast osteosarcoma. No residual tumor tissue was found at any cutting edge of the breast. Postoperative chemotherapy with ifosfamide and adriamycin was administered in 21 days per cycle, spread over 6 months. The patient had nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite during chemotherapy, but all were within the patient’s acceptable range. We established a follow-up plan that included outpatient visits every three months in the first year, every six months in the second year, and then annually or at longer intervals as clinically indicated. Each follow-up visit included a complete physical examination, a bone scan, chest imaging (mammography and chest CT), and functional scoring. After 12 months of follow-up, the patient’s overall condition was good, and no metastasis or recurrence was found on imaging. The patient was satisfied with the outcome of the treatment, and there were no obvious complications from the treatment.

3 DiscussionPOB is a rare and poorly differentiated tumor (9). The etiology of POB remains unclear, with reports suggesting associations with a history of burns, trauma, and even foreign bodies (2, 9, 10) and even radiation therapy (11, 12). Most patients have a several-year history of breast masses, with sudden short-term enlargement (2). In this case, the patient experienced the rapid formation of round, hard, heterogeneous, and well-defined masses during lactation. Clinically, lactation period is a high-risk period for purulent mastitis, which may also be a predisposing factor. Radiological features of POB often resemble those of benign tumors, typically showing hypoechoic diffuse coarse calcification, rich blood flow, and clear boundaries (13). Histopathology serves as the primary basis for distinguishing between benign and malignant tumors. Imaging tests such as ultrasound and CT have limited utility in differentiating purulent mastitis and POB (14).

For an accurate diagnosis of POB, a comprehensive evaluation of clinical, radiological, and pathological features is necessary. In this case report, the patient was misdiagnosed primarily because the initial general practitioner at a community hospital considered it a typical lactating mastitis based on their experience and after CDUS findings. Other diseases were not considered, mainly because the community physician very commonly encountered patients with breast nodules who had lactational mastitis. In addition, community hospitals lack breast specialists to provide counseling or use advanced diagnostic techniques to help detect breast tumors. It was not until the patient was transferred to the First Affiliated Hospital that the bacterial culture was performed, and the results were negative. Based on the negative bacterial culture results, the ineffectiveness of previous antibiotic therapy, and the rapid increase in the mass diameter from 3 cm to 10 cm in one month, the breast specialists at the First Affiliated Hospital felt that a malignant tumor needed to be considered. As a result, the patient underwent a pathological biopsy and immunohistochemistry, which revealed a typical malignant tumor pattern, leading to the diagnosis of POB after ruling out metastatic lesions.

POB shares histopathological similarities with extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) in other areas of the body, and POB must be distinguished from epithelial-derived metaplastic carcinomas of epithelial origin. Partial metaplastic carcinoma has few epithelial components and presents with atypical osteoid or chondroid tissues that are easily misdiagnosed as osteosarcomas (15). Collecting sufficient samples for the detection of malignant epithelial components is the primary method for differential diagnosis. The non-epithelial characteristics of this tumor were demonstrated by the immunohistochemical results, which were negative for AE1/3 and CK5/6 and positive for vimentin and SATB2. It should also be differentiated from malignant phyllodes tumors, and the key to its differential diagnosis is extensive sampling. Malignant phyllode tumors exhibit prominent stromal atypia and a fibrosarcomatoid appearance, and the intratumoral cystic cavity changes into narrow-branch (16). Benign bone islands coated with osteoblasts may be observed during benign bone tissue metaplasia. Differential diagnosis may involve bone scans and the absence of clinical evidence of extramammary soft tissue or bone osteosarcoma. Detection of neoplastic osteogenesis in breast metastases of osteoblastic osteosarcoma can be challenging, therefore, combining medical history and immunohistochemical staining is essential.

POB presents as an aggressive tumor prone to recurrence and blood system metastasis, characterized by rapid disease progression and a poor prognosis. The 5-year survival rate hovers around 38% (9). According to the literature, the 5-year survival rate of osseous osteosarcoma is reported to be 27.4% for patients with metastases at the initial diagnosis and 70% for patients without metastases (17). Alarmingly, over two-thirds of cases experience recurrence post-local resection, with 11% recurrence even after total mastectomy. In our investigation spanning from 2000 to 2023, we identified 29 patients (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1). All 29 patients with POB were female, aged between 24 and 96 years, with a median age of 67 years. Tumor diameters ranged from 1.4 to 18.0 cm, with a median diameter of 4.5 cm (2, 4, 7, 9, 18–35). Notably, none of the collected cases reported primary osteosarcoma of the breast during lactation. Our case findings revealed a 1-year survival rate of approximately 77.90% and an expected 3-year survival rate of about 53.68% (Supplementary Figure 2). Notably, we observed a correlation between poor prognosis in patients with POB and tumor volume as well as tumor stage (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). When comparing cumulative survival rates across POB stages I to IV, we found the 1-year cumulative survival rate to be the lowest in stage IV cases (Supplementary Figure 3). Presently, the standard treatment protocol for POB entails surgical intervention coupled with chemotherapy, primarily employing drugs such as adriamycin (ADM), cisplatin (DDP), and high-dose methotrexate (MTX) (36).

The current targeted therapy for POB is similar to that for common osteosarcoma and focuses on the following targets: The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein can hinder the growth of tumors by controlling the cell cycle of tumor cells. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can impact the behavior of tumor cells by influencing the development of blood vessels surrounding the tumor. Breast cancer (BRCA) genes can facilitate the repair of DNA damage and influence the advancement of osteosarcoma. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) may mediate specific pathways to impact tumor cells (37). Recent studies have highlighted the expression of PD-L1 in osteosarcoma cells, with inhibition of PD-1/PD-L1 expression proving beneficial in enhancing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte function (38, 39). Currently, clinical studies on the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab and the anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab are ongoing. A new targeted agent, glembatumumab vedotin (CDX-011), targets the transmembrane glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB; Osteoactivin) in a preclinical trial, three samples showed sustained complete remission after CDX-011 application (36). Furthermore, kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related (ATR) inhibition is a novel approach for osteosarcoma treatment. Osteosarcoma cells utilize an alternative mechanism of telomere elongation to overcome replicative senescence (40), a process commonly associated with ATRX loss. ATR inhibition disrupts this mechanism, leading to chromosome breakage and tumor cell apoptosis. Treatment with the ATR inhibitor VE-821 has shown heightened sensitivity and increased tumor cell death in ALT-positive osteosarcoma cell lines (41).

In the present case, radical mastectomy followed by chemotherapy proved effective using current treatment paradigms. However, vigilant follow-up is necessary to monitor the prognosis closely.

4 ConclusionIn conclusion, POB is a rare malignancy, and the exact mechanism of its occurrence remains unclear. It primarily metastasizes through the bloodstream, with the lungs being the most frequently affected site, and surgical resection is by far the most effective treatment modality. In the present case, the patient was initially misdiagnosed as having breast-feeding mastitis, and POB was diagnosed after surgical resection after ineffective anti-infection treatment. This suggests that the definite diagnosis of POB requires attention to immunohistochemistry, adequate pathological sampling, and detailed pathological analysis. This case report offers valuable insights for clinicians in identifying and diagnosing this condition.

Data availability statementThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statementThe studies involving humans were approved by Clinical Research Ethics Board of the First Affiliated Hospital, Shihezi University School of Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributionsHZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. YD: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. SD: Writing – original draft. JZ: Writing – original draft. ZW: Writing – original draft. LM: Writing – original draft. CW: Writing – original draft. ML: Writing – original draft. XY: Writing – original draft. NW: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision. JH: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

FundingThe author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from Guiding scientific and technological research project in the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No.2022ZD003, No.2023ZD028), Basic Research Project of Shihezi University (No.MSPY202407), Innovative Development Project of Shihezi University (CXFZ202305).

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank this patient for her participation. In addition, we appreciate the Pathological Diagnosis Clinical Medical Research Center of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps for their helpful assistance.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1362024/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Flow chart for screening POB literature.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Cumulative survival analysis of 29 patients with POB.

Supplementary Figure 3 | The cumulative survival rate of POB patients in stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV.

References1. Gull S, Patil P, Spence RA. Primary osteosarcoma of breast. Case Rep. (2011) 2011:bcr0320114015–bcr0320114015. doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.4015

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Bahrami A, Resetkova E, Ro JY, Ibañez JD, Ayala AG. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2007) 131:792–5. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-792-POOTBR

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Mujtaba B, Nassar SM, Aslam R, Garg N, Madewell JE, Taher A, et al. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast: pathophysiology and imaging review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. (2020) 49:116–23. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2019.01.001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Zhao J, Zhang X, Liu J, Li J. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast with abundant chondroid matrix and fibroblasts has a good prognosis: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. (2013) 6:745–7. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1446

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Szajewski M, Kruszewski WJ, Ciesielski M, Śmiałek-Kusowska U, Czerepko M, Szefel J. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast: A case report. Oncol Lett. (2014) 7:1962–4. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1981

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Yahaya JJ, Odida M. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast with extensive chondroid matrix in a teenager female patient: the paradoxical diagnosis in breast mastopathy. Int Med Case Rep J. (2020) 13:11–7. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S233674

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Meunier B, Levêque J, Le Prisé E, Kerbrat P, Grall JY. Three cases of sarcoma occurring after radiation therapy of breast cancers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (1994) 57:33–6. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90107-4

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Alpert LI, Abaci IF, Werthamer S. Radiation-induced extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. (1973) 31:1359–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197306)31:6<1359::AID-CNCR2820310609>3.0.CO;2-F

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Bennett DL, Merenda G, Schnepp S, Lowdermilk MC. Primary breast osteosarcoma mimicking calcified fibroadenoma on screening digital breast tomosynthesis mammogram. Radiol Case Rep. (2017) 12:648–52. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.06.008

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Conti A, Duggento A, Indovina I, Guerrisi M, Toschi N. Radiomics in breast cancer classification and prediction. Semin Cancer Biol. (2021) 72:238–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.04.002

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Reddy TP, Rosato RR, Li X, Moulder S, Piwnica-Worms H, Chang JC. A comprehensive overview of metaplastic breast cancer: clinical features and molecular aberrations. Breast Cancer Res. (2020) 22:121. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01353-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Fede ÂBDS, Pereira Souza R, Doi M, De Brot M, Aparecida Bueno De Toledo Osorio C, Rocha Melo Gondim G, et al. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast: A practice review. Clin Pract. (2021) 11:205–15. doi: 10.3390/clinpract11020030

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Bacci G, Rocca M, Salone M, Balladelli A, Ferrari S, Palmerini E, et al. High grade osteosarcoma of the extremities with lung metastases at presentation: Treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and simultaneous resection of primary and metastatic lesions. J Surg Oncol. (2008) 98:415–20. doi: 10.1002/jso.21140

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Trihia H, Valavanis C, Markidou S, Condylis D, Poulianou E, Arapantoni-Dadioti P. Primary osteogenic sarcoma of the breast. Acta Cytol. (2007) 51:443–50. doi: 10.1159/000325764

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Kallianpur A, Gupta R, Muduly D, Kapali A, Subbarao K. Osteosarcoma of breast: A rare case of extraskeletal osteosarcoma. J Cancer Res Ther. (2013) 9:292. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.113392

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Rizzi A, Soregaroli A, Zambelli C, Zorzi F, Mutti S, Codignola C, et al. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast: A case report. Case Rep Oncol Med. (2013) 2013:858705. doi: 10.1155/2013/858705

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Gafumbegete E, Fahl U, Weinhardt R, Respondek M, Elsharkawy AE. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast after complete resection of a metaplastic ossification: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2016) 10:231. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-1008-2

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Billups CA, Hawthorne T, Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of glembatumumab vedotin (CDX-011) by the pediatric preclinical testing program: Preclinical Testing of Glembatumumab Vedotin. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2014) 61:1816–21. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25099

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Shen JK, Cote GM, Choy E, Yang P, Harmon D, Schwab J, et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol Res. (2014) 2:690–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0224

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Lussier DM, O’Neill L, Nieves LM, McAfee MS, Holechek SA, Collins AW, et al. Enhanced T-cell immunity to osteosarcoma through antibody blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions. J Immunother. (2015) 38:96–106. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000065

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Scheel C, Schaefer K-L, Jauch A, Keller M, Wai D, Brinkschmidt C, et al. Alternative lengthening of telomeres is associated with chromosomal instability in osteosarcomas. Oncogene. (2001) 20:3835–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204493

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Flynn RL, Cox KE, Jeitany M, Wakimoto H, Bryll AR, Ganem NJ, et al. Alternative lengthening of telomeres renders cancer cells hypersensitive to ATR inhibitors. Science. (2015) 347:273–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1257216

留言 (0)