Heat-related illnesses are a significant global health concern, affecting a substantial number of individuals annually. Escalating global temperatures due to climate change have intensified the frequency and severity of heat-related illnesses (Robine et al., 2008). These range from mild conditions, such as heat-induced syncope and cramps, to severe conditions, such as heat exhaustion and life-threatening heatstroke (Bouchama and Knochel, 2002; Savioli et al., 2022; Barletta et al., 2024). Heatstroke is a medical emergency associated with a high mortality rate of 20–60% (Bouchama et al., 2022). The pathophysiology of acute severe heatstroke is complex and may involve multiple organ systems, leading to complications such as rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute renal failure, liver damage, acute respiratory distress syndrome, electrolyte imbalances, and neurological complications (Dematte et al., 1998; Pechlaner et al., 2002; Bouchama and Knochel, 2002; Lawton et al., 2019). Neurological complications include cerebellar ataxia, cognitive impairment, dysphagia, and aphasia (Lawton et al., 2019).

This mini review aimed to highlight the importance of understanding the mechanisms and pathways underlying brain injury induced by heatstroke and identifying diagnostic imaging tools and biomarkers crucial for developing targeted management strategies. Most recent advancements in this field are summarized and discussed.

2 Review 2.1 Heatstroke: a growing concern in a warming worldHeatstroke, a severe form of heat-related illness, is becoming increasingly common owing to rising global temperatures (Bouchama and Knochel, 2002). Heatstroke is characterized by a core body temperature exceeding 40°C (104°F), leading to central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction (Becker and Stewart, 2011; Bouchama et al., 2022). Heatstroke can be classified into two types: classical (non-exertional) heatstroke, which typically affects vulnerable populations such as older adults and infants, and exertional heatstroke, which is more common among young, healthy individuals engaged in physical activities (Gaudio and Grissom, 2016; Hifumi et al., 2018). According to the World Health Organization, approximately 166,000 individuals succumbed to heatstroke between 1998 and 2017, with the 2003 European heat wave alone resulting in an estimated 70,000 deaths (Robine et al., 2008). The occurrence of heatstroke varies worldwide, and factors that increase the risk of heatstroke are geographical locations with high temperatures, limited access to cooling resources, and inadequate public health infrastructure (Rublee et al., 2021) (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2 Classification and pathology of heatstrokeHeat-related illnesses encompass a spectrum of conditions resulting from the body’s inability to adequately adapt to the stresses imposed by high-temperature environments. Historically, heat-related illnesses have been classified according to the presence or absence of exertion, symptoms, or temperature; however, the lack of a globally uniform definition has made comparisons difficult. In Japan, a classification stratified by severity, as shown in Supplementary Table S2, has become widespread (Hifumi et al., 2018). Under normal physiological conditions, an increase in core body temperature activates the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, inducing adaptive mechanisms, such as sweating and increased skin blood flow, to dissipate excess heat. Dilation of blood vessels facilitates the distribution of cooler blood throughout the body. However, dehydration can reduce the overall blood volume, leading to diminished cerebral perfusion and symptoms, such as headaches and altered consciousness, known as heat syncope. Concurrently, the process of sweating, while aiding thermoregulation through cooling by evaporation, also results in remarkable electrolyte losses, particularly sodium (Na+), leading to muscle cramps and spasms. Accordingly, the initial management of heat-related illness generally includes the use of oral rehydration solutions and/or moving the individual to a cooler environment. Impacts of dehydration and fatigue can exacerbate the condition, with progression to second-degree heatstroke, also known as heat exhaustion, which necessitates medical intervention. Further progression of the condition results in the cessation of sweating and, if unchecked, increase in core temperature, culminating in third-degree heatstroke, characterized by widespread organ damage, including endothelial injury.

2.3 Pathophysiology of heatstroke and mechanism of body temperature elevationThe pathophysiology of heatstroke is characterized by the failure of thermoregulation, leading to systemic inflammation, coagulopathy, and multi-organ dysfunction, encompassing acute renal failure, liver damage, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Hifumi et al., 2018; Iba et al., 2022). Systemic effects of thermoregulation failure are exacerbated by profound dehydration-induced circulatory failure, direct thermal damage, and hyper-cytokinemia (Hifumi et al., 2018; Bouchama et al., 2022). The interplay between inflammation and coagulation plays a pivotal role in propagating organ dysfunction, with heat-induced damage triggering a cascade of cellular and molecular responses that exacerbate vascular permeability and coagulopathy, leading to DIC and multi-organ failure. When damaged, cells release damage-associated molecular proteins (DAMPs), such as high mobility group box (HMGB)-1, histones, and DNA. DAMPs activate inflammasomes through pattern recognition receptors, causing an inflammatory response through the release of cytokines (Iba et al., 2022).

Similar to sepsis and trauma, heatstroke causes a systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome (SIRS) following hyperthermia (Bouchama et al., 2022).

Heat-induced SIRS results from a failure of thermoregulation and elevation in core temperature, which directly damages endothelial cells, leukocytes, and epithelial cells. Cell damage causes release of DAMPs, such as HMGB-1, histones, and DNA, which bind to pattern recognition receptors (PPRs), such as toll-like receptors and inflammasomes. It progressively worsens vascular permeability and coagulopathy, leading to DIC and multiple organ failure (Epstein and Yanovich, 2019).

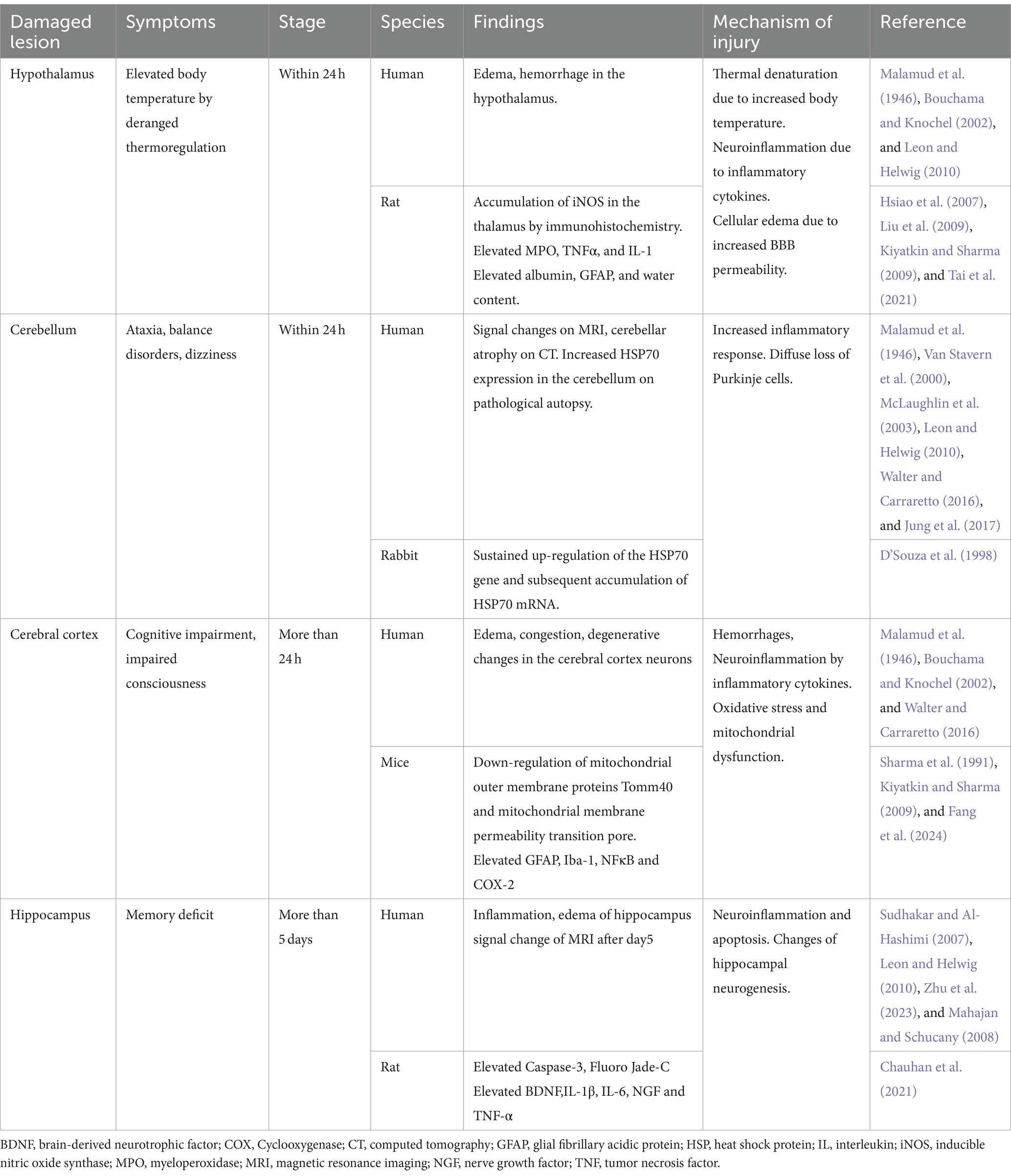

2.4 Heatstroke damages various areas in the brain (Table 1)

Table 1. Brain damage and heatstroke.

The hypothalamus is considered the thermoregulatory center of the body, but it is also vulnerable to heat stress. Tai et al. revealed that myeloperoxidase, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1 are elevated in the hypothalamus in a rat heatstroke model (Tai et al., 2021). Hsiao et al. demonstrated through immunohistochemistry that iNOS accumulates in the hypothalamus in rat heatstroke models (Hsiao et al., 2007). Immunohistochemistry showed considerable increases in GFAP, Iba1, NF-κB, and COX-2 (Chauhan et al., 2017). Heatstroke has been confirmed to damage nerve cells and even induce inflammation (Liu et al., 2009).

In the brain, the cerebellum is deemed the most vulnerable tissue to heat stress and is among the first areas to show signs of damage (Bazille et al., 2005). In patients who died within 24 h of heatstroke, edema had already begun in the Purkinje layer, and the number of Purkinje cells had decreased. Malamud et al. (1946) reported that by the third day, almost no Purkinje cells remained, having undergone coagulation. Li et al. (2015), in a brain MRI study, showed that fractional anisotropy was markedly higher in the cerebellum of patients with heatstroke than that of healthy individuals. Bazille et al. (2005) also showed that Purkinje cells were gradually lost in the cerebellum, accompanied by HSP70 expression in the pathological gyrus and cerebellum of three patients who had died from heatstroke. Additionally, in experiments with heatstroke rabbits, persistent upregulation of the HSP70 gene and subsequent accumulation of HSP70 mRNA have been reported (D’Souza et al., 1998). There are case reports of dizziness and nystagmus as cerebellar symptoms 1 week after the onset of heatstroke (Van Stavern et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2017).

Changes in the cerebral cortex begin to appear after 24 h. According to the pathological autopsy results of Malamud et al. (1946), no significant changes occurred up to 18 h; however, after 24 h, the number of neurons decreased and glia began to proliferate. In a juvenile rat heatstroke model by Sharma et al. (1991), neurons in the cerebral cortex darkened and astrocytes swelled. At the microstructural level, microvessels collapsed, and perivascular edema, cavitation, and synaptic damage were observed. When the cFos protein was examined to evaluate the localization of brain damage in a mouse heatstroke model, the most significant damage was observed in the anterior cingulate cortex of the cerebral cortex. In addition, a multi-omics analysis of the cerebral cortex conducted in the same study revealed that considerable changes occurred in pathways related to neurotransmission, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress (Fang et al., 2024).

Reports reveal that MRI signals in the hippocampus begin to show changes from approximately the fifth day (Sudhakar and Al-Hashimi 2007; Mahajan and Schucany, 2008). Zhu et al. (2023) reported that heat stress changes the levels of inflammatory mediators secreted by glial cells. This induces neuroinflammation, impairing neurogenesis in the hippocampus and resulting in cognitive dysfunction. In a rat heatstroke model by Chauhan et al. (2021), increased levels of caspase 3 and Fluoro Jade-C were observed in the hippocampus, indicating apoptosis and neuronal damage in the hippocampus.

2.5 How can heatstroke damage the brain?Research has documented that the brain is one of the organs most vulnerable to hyperthermia (Malamud et al., 1946). Heatstroke can lead to neurological complications, such as cerebellar ataxia, cognitive impairment, dysphagia, and aphasia (Leon and Bouchama, 2015). Long-term studies have revealed cellular damage in various brain regions, including the cerebellum, hippocampus, midbrain, and thalamus (Lawton et al., 2019). Hyperthermic stress, resulting from external temperature elevation and thermoregulation failure, leads to elevated temperature in brain tissues.

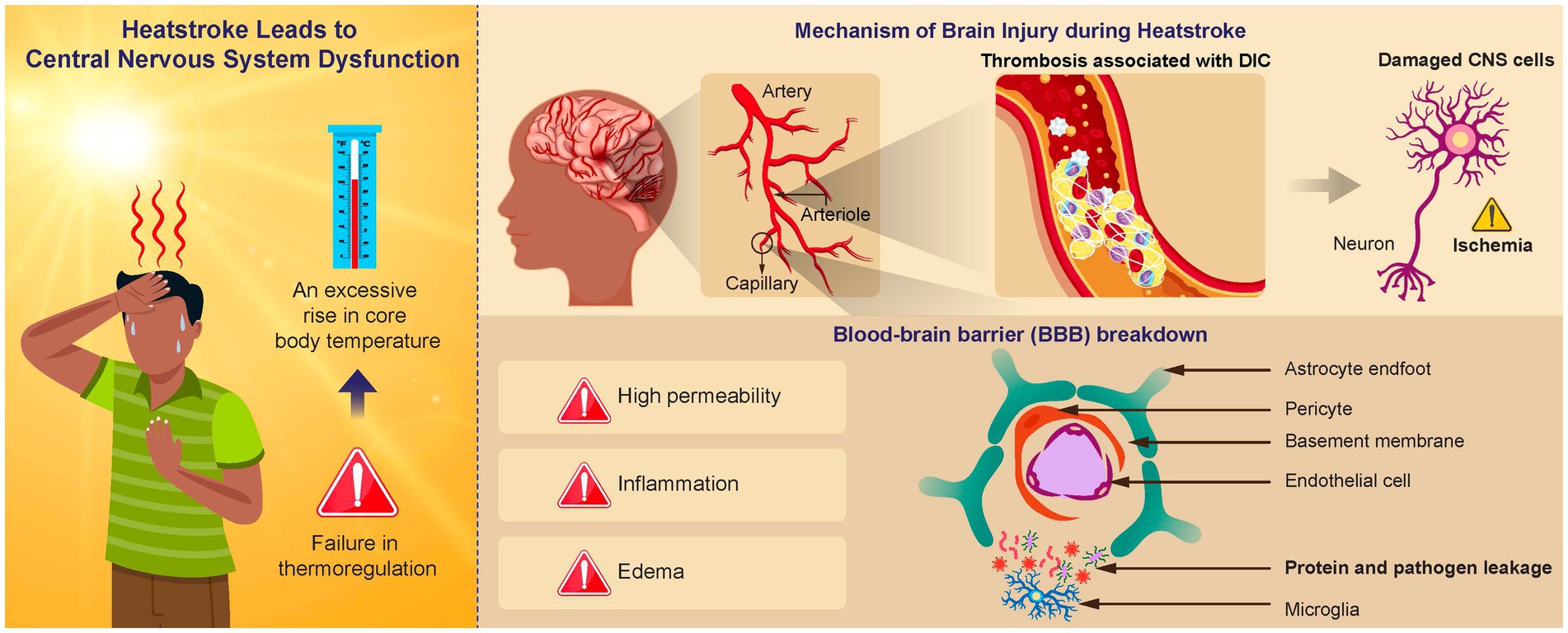

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a dynamic system for the exchange of substances between the blood and brain parenchyma and is an essential functional gatekeeper of the CNS (Hu and Tao, 2021). The BBB integrity is crucial for maintaining CNS homeostasis (Segarra et al., 2021). The tightness and integrity of the BBB vary in response to multiple factors, including environmental and systemic factors. Of these, extreme temperatures have been reported to affect BBB permeability (Kiyatkin and Sharma, 2009), with a decrease in brain blood supply and an increase in intracranial pressure resulting from a compromised BBB.

In addition to the direct effects of heat, we cannot ignore the indirect effects from multiple organs. A typical example is the intestinal tract. SIRS following hyperthermia damages intestinal epithelial cells, causing the relaxation of tight junctions, and bacteria and endotoxins from the intestinal tract enter the lymphatic flow (Gupta et al., 2017). This is referred to as bacterial translocation. Bacteria and endotoxins that invade the lymphatic stream act as danger signals (alermin) to the organism, which activate the inflammasome, the source of inflammation, via PRRs. The activated inflammasome activates proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Yin et al., 2022). These cytokines also increase vascular permeability in the CNS, leading to angiogenic and cytotoxic edema (Du et al., 2024). This enhanced leakage of proteins and pathogens from the systemic circulation to the brain leads to an inflammatory response that affects normal brain function in the chronic phase.

Heat also causes injury to vascular epithelial cells. The superficial layer of vascular endothelial cells contains a protective layer called glycocalyx. SIRS following hyperthermia damages this layer, allowing albumin and fluid components to leak out of the vessel into the interstitium, leading to edema of the interstitium (Kobayashi et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2023). Glycocalyx also plays a role in inhibiting intravascular thrombus formation, and its injury promotes intravascular thrombus formation. Both factors lead to blood flow injury (Peng et al., 2023). This also causes intracranial induction, resulting in a natural reduction of cerebral blood flow. Decreased cerebral blood flow leads to hypoxia of the brain parenchyma.

Thus, hyperthermia-associated SIRS leads to direct and indirect damage to the brain tissue, resulting in CNS symptoms such as impaired consciousness and coma (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanism of brain injury in heatstroke. An elevated brain temperature causes cell damage within the central nervous system (CNS) and disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Vasogenic and cytotoxic edema can result from increased BBB permeability, which facilitates protein and pathogen leakage from the systemic circulation into the brain. This leakage causes an inflammatory response, negatively affecting normal functioning. Activation of the inflammation and coagulation responses can result in the formation of immune thrombosis in the brain microvasculature, leading to an ischemic change in the CNS.

2.6 Neuroimaging for heatstrokeThe initial CT of patients suffering from heatstroke typically does not show any abnormalities (Albukrek et al., 1997) or only shows indirect signs of brain swelling (Szold et al., 2002). Previous MRI studies have identified lesions in different parts of the brain, including the external capsule, internal capsule, splenium, basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus, frontal and parietal cortex, insula, and subcortical white matter (McLaughlin et al., 2003; Sudhakar and Al-Hashimi 2007; Mahajan and Schucany, 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Fatih Yilmaz et al., 2018; Lee, 2020; Shimada et al., 2020). These lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI sequences. Most reported cases show cytotoxic swelling at different parts of the brain and cerebellar atrophy at 90 days post-heatstroke event (Szold et al., 2002; Mahajan and Schucany, 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Lee, 2020; Shimada et al., 2020). These findings suggest cerebral venous thrombosis, micro-level ischemia, and hemorrhagic processes related to heatstroke. Other imaging modalities include contrast-enhanced sequences that might reveal disruptions in the BBB due to vascular or inflammatory processes. Single-photon emission CT (SPECT) is excellent for evaluating brain hemodynamics. SPECT images are reported to be useful for predicting sequelae (Suzuki et al., 2023).

2.7 Gene expression and heatstrokeSeveral factors predispose to the development of heatstroke (Walter and Carraretto, 2015), among which genetic predisposition as an intrinsic cause of heatstroke is particularly notable. Conducting research to understand the detailed molecular pathogenesis of heat-related diseases and develop new diagnostic methods is crucial (Bouchama et al., 2022).

Recent advances in sequencing and other technologies have made it possible to comprehensively evaluate genes and gene expression using clinical specimens. Using these new techniques, heatstroke can be evaluated from the perspective of its molecular pathogenesis (Supplementary Table S3). For example, Oda et al. (2019) measured carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT II), which is important for mitochondrial energy production, in patients with heatstroke and healthy controls. It is known that patients with a CPT II phenotype of [1,055 T > G/FF352C] cannot produce sufficient energy in a hyperthermic environment. It was also revealed that the prognosis of patients with severe heatstroke who exhibit this phenotype is poor (Oda et al., 2019). Identifying the expression of these genes by qRT-PCR may lead to the early detection of heatstroke and the development of therapeutic agents targeting specific molecules. Various genes related to heatstroke have been identified; however, those related to the prognosis of brain damage (e.g., biomarkers) require more research.

2.8 Role of biomarkers in predicting heatstroke neurological outcomesBiomarkers play a crucial role in predicting the outcomes of patients with heatstroke by detecting early organ injury and guiding the development of novel therapeutic strategies for organ preservation. These biomarkers, obtained from biological samples of patients with heatstroke, help identify tissue damage, predict outcomes, and monitor recovery or repair failure. Various biomarkers have been identified in different organs affected by heatstroke, such as HMGB1 (Tong et al., 2011), plasma and urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in the kidneys, intestinal fatty acid-binding protein 2 in the intestines, and creatine kinase and myoglobin in skeletal muscles (Schlader et al., 2022). Serum S100β and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) have attracted attention as CNS biomarkers (Supplementary Table S4) (Persson et al., 1987). S100β is a glial cell-specific protein expressed mainly in astrocytes and functions as a neurotrophic factor. S100β is secreted by damaged cells, with elevation in levels early after CNS injury (Papa et al., 2016). NSE is derived from neurons and is elevated in the blood following neuronal injury when the BBB is compromised. NSE is a protein of the myelin sheath and, thus, is elevated with myelin injury (Zhang et al., 2024). NSE is used as a biomarker for various neurological diseases, such as traumatic brain injury and stroke (Schlader et al., 2022). NSE is also gaining attention as a biomarker of heatstroke. First, it has been reported that S100β in serum and spinal fluid increases in heatstroke. A five-fold increase in serum S100β levels was reported in patients with a poor prognosis compared to those with a good prognosis (Chun et al., 2019), with the increase in S100β level resulting from impaired function of the BBB under high-temperature conditions (Watson et al., 2005). There is a strong correlation between NSE levels and neurological outcomes up to day seven after a heatstroke (Schlader et al., 2022). Myelin basic protein in the spinal fluid is also elevated in heatstroke owing to injury to the myelin sheath and the resulting neuronal damage with increasing core temperature. In contrast, the spinal and serum levels of IL-6, a marker of early inflammation, are typically low in heatstroke. This suggests that changes in the structural protein levels are a causative factor of heatstroke before the onset of inflammation (Ikeda et al., 2021). In addition, glial fibrillary acid protein and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 are other known neural biomarkers; however, no studies have demonstrated their association with increased body temperature or neurological outcomes in heatstroke (Stacey et al., 2023). Further research is needed to translate these biomarkers into clinical practice and understand their utility in predicting long-term health outcomes following heatstroke.

2.9 Heatstroke and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)The blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) in the choroid plexus cooperates with the cerebral blood barrier to regulate the CSF and stabilize the neuronal environment. Heat stress can damage the BCSFB, leading to cerebral edema and reduced cerebral blood flow, resulting in the leakage of various proteins and cytokines into the CSF (Sharma and Johanson, 2007; Hashim, 2010). As noted in section 2.8, S100β and NSE are the most frequently reported biomarkers associated with heatstroke and CSF abnormalities. They are elevated in nervous system cell damage as well as in patients with poor neurological prognosis (Persson et al., 1987; Frosini et al., 2000; Frosini, 2007; Chun et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Schlader et al., 2022). Although these markers can also be measured in serum, the CSF may reveal more subtle changes, with some reports indicating higher values in the CSF. Additionally, elevated levels of neurofilament light chain, suggesting axonal degeneration, as well as amino acids such as taurine and GABA, and inflammatory cytokines have been observed (Hashim, 2010; Lin et al., 2018; Gaetani et al., 2019; Azcue et al., 2024). While no studies directly compare the effectiveness of these CSF tests with other diagnostic methods, CSF testing offers advantages such as ease of sampling and earlier detection of changes compared to imaging tests. It also provides valuable insights into neurological prognosis; thus, selecting the appropriate test should consider the disease stage and specific clinical setting.

2.10 Management of heatstrokeThe primary treatment for heatstroke involves rapid cooling to lower body temperature. Ice-water immersion is considered the gold standard for treating exertional heatstroke (Kim et al., 2020), particularly in young, fit individuals and has demonstrated a zero-fatality rate in large case series (Gaudio and Grissom, 2016). Other cooling methods include evaporative cooling using mist sprays and fans; Tarp-Assisted Cooling Oscillation (TACO) as an alternative when ice-water immersion is unavailable; strategic application of ice packs to cool the neck, axilla, and groin; cooling infusions; and intravascular and body surface cooling devices (Gaudio and Grissom, 2016; Luhring et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2020). The prompt initiation of cooling measures is crucial to prevent irreversible organ damage (Gaudio and Grissom, 2016). Supportive care is essential to manage complications and support organ function.

Techniques for cooling patients with hyperthermia are similar to those used for targeted temperature management after cardiac arrest or traumatic brain injury (Behr et al., 1997; Zeiner et al., 2001; Rossi et al., 2001; Wakino et al., 2005). These techniques include the administration of cold intravenous fluid; gastric, peritoneal, pleural, and/or bladder lavage with cold water; and the use of intravascular cooling techniques, such as cooling catheters and extracorporeal circuits (continuous venovenous hemofiltration or cardiopulmonary bypass). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, equipped with a blood cooling system, to achieve rapid whole-body cooling and brain cryotherapy for temperature control has been reported to be effective in treating abnormal hyperthermia and brain swelling accompanied by impaired consciousness in severe heatstroke (Fujita et al., 2021).

Using an intravascular cooling system has been reported as an active cooling treatment for heatstroke, and in cases where multiple factors contribute to the onset of sequelae and poor prognosis, invasive treatment should also be considered. However, simply normalizing body temperature may not be enough to fully prevent CNS damage, as it does not address inflammatory reactions, coagulation abnormalities, or vascular endothelial damage caused by excessive cytokines (Bouchama and Knochel, 2002). Previous animal experiments have shown a reduction in mortality and CNS damage with the administration of activated protein C (Chen et al., 2006; Brueckmann et al., 2006) and hyperbaric oxygen therapy for heatstroke (Tsai et al., 2005). In addition to active cooling treatment and systemic management, future treatment strategies should also focus on protecting the CNS.

3 ConclusionIn this mini review, we describe the clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment of heatstroke. Additionally, we highlight the importance of understanding the underlying mechanisms of brain injury and identifying diagnostic biomarkers. Further research is needed to develop more effective treatment strategies and understand the long-term health consequences of heatstroke.

Author contributionsKY: Writing – original draft. SH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HI: Writing – original draft. YT: Writing – original draft. SO: Writing – original draft. HM: Writing – original draft. JS: Writing – original draft. HO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [grant numbers 21K09016 and 24K12177] and the General Insurance Association of Japan. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2024.1437216/full#supplementary-material

ReferencesAlbukrek, D., Bakon, M., Moran, D. S., Faibel, M., and Epstein, Y. (1997). Heat-stroke-induced cerebellar atrophy: clinical course, CT and MRI findings. Neuroradiology 39, 195–197. doi: 10.1007/s002340050392

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Azcue, N., Tijero-Merino, B., Acera, M., Pérez-Garay, R., Fernández-Valle, T., Ayo-Mentxakatorre, N., et al. (2024). Plasma neurofilament light chain: a potential biomarker for neurological dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Biomedicines 12:1539. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12071539

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Barletta, J. F., Palmieri, T. L., Toomey, S. A., Harrod, C. G., Murthy, S., and Bailey, H. (2024). Management of heat-related illness and injury in the ICU: a concise definitive review. Crit. Care Med. 52, 362–375. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006170

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bazille, C., Megarbane, B., Bensimhon, D., Lavergne-Slove, A., Baglin, A. C., Loirat, P., et al. (2005). Brain damage after heat stroke. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64, 970–975. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000186924.88333.0d

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Behr, R., Erlingspiel, D., and Becker, A. (1997). Early and longtime modifications of temperature regulation after severe head injury. Prognostic implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 813, 722–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51774.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bouchama, A., Abuyassin, B., Lehe, C., Laitano, O., Jay, O., O’Connor, F. G., et al. (2022). Classic and exertional heatstroke. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 8:8. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00334-6

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Cao, L., Wang, J., Gao, Y., Liang, Y., Yan, J., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance venography features in heat stroke: a case report. BMC Neurol. 19:133. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1363-x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chauhan, N. R., Kapoor, M., Prabha Singh, L., Gupta, R. K., Chand Meena, R., Tulsawani, R., et al. (2017). Heat stress-induced neuroinflammation and aberration in monoamine levels in hypothalamus are associated with temperature dysregulation. Neuroscience. 358, 79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.06.023

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chauhan, N. R., Kumar, R., Gupta, A., Meena, R. C., Nanda, S., Mishra, K. P., et al. (2021). Heat stress induced oxidative damage and perturbation in BDNF/ERK1/2/CREB axis in hippocampus impairs spatial memory. Behav. Brain Res. 396:112895. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112895

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, C.-M., Hou, C.-C., Cheng, K.-C., Tian, R.-L., Chang, C.-P., and Lin, M.-T. (2006). Activated protein C therapy in a rat heat stroke model. Crit. Care Med. 34, 1960–1966. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000224231.01533.B1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chun, J.-K., Choi, S., Kim, H.-H., Yang, H. W., and Kim, C. S. (2019). Predictors of poor prognosis in patients with heat stroke. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 6, 345–350. doi: 10.15441/ceem.18.081

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

D’Souza, C. A., Rush, S. J., and Brown, I. R. (1998). Effect of hyperthermia on the transcription rate of heat-shock genes in the rabbit cerebellum and retina assayed by nuclear run-ons. J. Neurosci. Res. 52, 538–548. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980601)52:5<538::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-D

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dematte, J. E., O’Mara, K., Buescher, J., Whitney, C. G., Forsythe, S., McNamee, T., et al. (1998). Near-fatal heat stroke during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann. Intern. Med. 129, 173–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00001

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Du, G., Yang, Z., Wen, Y., Li, X., Zhong, W., Li, Z., et al. (2024). Heat stress induces IL-1β and IL-18 overproduction via ROS-activated NLRP3 inflammasome: implication in neuroinflammation in mice with heat stroke. Neuroreport 35, 558–567. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000002042

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Fang, W., Yin, B., Fang, Z., Tian, M., Ke, L., Ma, X., et al. (2024). Heat stroke-induced cerebral cortex nerve injury by mitochondrial dysfunction: a comprehensive multi-omics profiling analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 919:170869. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170869

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Fatih Yilmaz, T., Aralasmak, A., Toprak, H., Guler, S., Tuzun, U., and Alkan, A. (2018). MRI and MR spectroscopy features of heat stroke: a case report. Iran. J. Radiol. 15:e62386. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.62386

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Frosini, M. (2007). Changes in CSF composition during heat stress and fever in conscious rabbits. Prog. Brain Res. 162, 449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)62022-0

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Frosini, M., Sesti, C., Palmi, M., Valoti, M., Fusi, F., Mantovani, P., et al. (2000). Heat-stress-induced hyperthermia alters CSF osmolality and composition in conscious rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279, R2095–R2103. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2095

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Fujita, M., Miyazaki, K., Horiguchi, M., Yamamoto, K., Ito, S., and Fukushima, H. (2021). Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe heatstroke with refractory hemodynamic failure. Case Rep. Acute Med. 4, 76–79. doi: 10.1159/000517681

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Gaetani, L., Blennow, K., Calabresi, P., Di Filippo, M., Parnetti, L., and Zetterberg, H. (2019). Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90, 870–881. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Gupta, A., Chauhan, N. R., Chowdhury, D., Singh, A., Meena, R. C., Chakrabarti, A., et al. (2017). Heat stress modulated gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction: role of tight junctions and heat shock proteins. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 52, 1315–1319. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1377285

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hifumi, T., Kondo, Y., Shimizu, K., and Miyake, Y. (2018). Heat stroke. J. Intensive Care 6:30. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0298-4

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hsiao, S.-H., Chang, C.-P., Chiu, T.-H., and Lin, M.-T. (2007). Resuscitation from experimental heatstroke by brain cooling therapy. Resuscitation 73, 437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.003

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hu, Y., and Tao, W. (2021). Microenvironmental variations after blood-brain barrier breakdown in traumatic brain injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14:750810. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.750810

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Iba, T., Connors, J. M., Levi, M., and Levy, J. H. (2022). Heatstroke-induced coagulopathy: biomarkers, mechanistic insights, and patient management. EClinicalMedicine 44:101276. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101276

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ikeda, T., Tani, N., Watanabe, M., Hirokawa, T., Ikeda, K., Morioka, F., et al. (2021). Evaluation of cytokines and structural proteins to analyze the pathology of febrile central nervous system disease. Leg. Med. (Tokyo) 51:101864. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2021.101864

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, D. A., Lindquist, B. D., Shen, S. H., Wagner, A. M., and Lipman, G. S. (2020). A body bag can save your life: a novel method of cold water immersion for heat stroke treatment. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 1, 49–52. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12007

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kiyatkin, E. A., and Sharma, H. S. (2009). Permeability of the blood-brain barrier depends on brain temperature. Neuroscience 161, 926–939. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.004

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kobayashi, K., Mimuro, S., Sato, T., Kobayashi, A., Kawashima, S., Makino, H., et al. (2018). Dexmedetomidine preserves the endothelial glycocalyx and improves survival in a rat heatstroke model. J. Anesth. 32, 880–885. doi: 10.1007/s00540-018-2568-7

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lawton, E. M., Pearce, H., and Gabb, G. M. (2019). Review article: environmental heatstroke and long-term clinical neurological outcomes: a literature review of case reports and case series 2000–2016. Emerg. Med. Australas. 31, 163–173. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12990

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, B. H. (2020). Atypical brain imaging findings associated with heat stroke: a patient with rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury: a case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 15, 560–563. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.02.007

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, J. S., Choi, J. C., Kang, S. Y., Kang, J. H., and Park, J. K. (2009). Heat stroke: increased signal intensity in the bilateral cerebellar dentate nuclei and splenium on diffusion-weighted MR imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 30:E58. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1432

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, B., Jia, Y.-R., Gao, W., Li, H.-P., Tao, W.-H., and Zhang, H.-X. (2020). The expression and clinical significance of neuron specific enolase and S100B protein in patients of severe heatstroke-induced brain injury. Med. J. Chin. Peoples Liberation Army 45, 1282–1287.

Li, J., Zhang, X.-Y., Wang, B., Zou, Z.-M., Wang, P.-Y., Xia, J.-K., et al. (2015). Diffusion tensor imaging of the cerebellum in patients after heat stroke. Acta Neurol. Belg. 115, 147–150. doi: 10.1007/s13760-014-0343-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, Y.-F., Liu, T.-T., Hu, C.-H., Chen, C.-C., and Wang, J.-Y. (2018). Expressions of chemokines and their receptors in the brain after heat stroke-induced cortical damage. J. Neuroimmunol. 318, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.01.014

留言 (0)