The term NORSE (New Onset Refractory Status Epilepticus) (1) was first used in 2005 to describe 7 cases (females, mean age 33 yrs., range 20–52 yrs) of status epilepticus (SE) refractory to standard treatment protocols with a poor outcome (5 died, 2 were in vegetative state) in whom a previous history of epilepsy or underlying cause was not identified. Five year later, “FIRES” (Febrile Infection-Related Epilepsy Syndrome) emerged as a clinical entity describing a case-series of 22 previously typically developing children (3–15 yrs) with prolonged or recurrent seizures occurring ~5 days after fever onset (2, 3). In 2018, an expert group released a Consensus definition of New-Onset Refractory Status Epilepticus (NORSE) (4) as a clinical presentation, not a specific diagnosis, in a patient without active epilepsy or other pre-existing relevant neurological disorder, with new onset of refractory status epilepticus (RSE) without a clear acute or active structural, toxic, or metabolic cause but including patients with viral or autoimmune causes. FIRES was designated a subtype of NORSE where, following a minor febrile illness, seizures increase rapidly (100 s/day) and worsen to SRSE (4). Previously the term FIRES was used exclusively in children, however, it is now accepted that children can have NORSE and adults can have FIRES.

Despite progress in the clarification of NORSE/FIRES as a clinical syndrome, understanding of the underlying pathogenic mechanisms is limited. A cryptogenic cause accounts for up to 50% (5) of cases with these cases reported to have worst outcomes (6).

Treatment of FIRES/NORSE is challenging, and traditional antiseizure medicines (ASMs) used in status epilepticus often prove ineffective against the unrelenting ictal activity (7). All the available evidence for NORSE/FIRES treatment is from case-series, there have been no systematic clinical trials to date. As positive results from therapies are more likely to be published, the bias in treatment responsiveness needs acknowledgement. A Delphi expert consensus on a suggested treatment algorithm was recently published (2) stating initial treatment of SE and RSE with ASMs and anesthetic drugs as per published and local guidelines, and management of possible infections alongside diagnostic work-up and treatment for etiology if identified. If there is incomplete response then initiation of first-line immunological treatment (steroids, IVIG, PLEX) within the first 72 h of seizures is recommended. If ongoing unresponsiveness to treatment, children (and adults if possible) can be started on the ketogenic diet, followed by second-line immunological treatment [including IL-1Ra and IL-6 antagonists (if cryptogenic), and Rituximab (if neuronal autoantibody identified or autoimmune encephalitis suspected)]. Other treatments published in case reports and small case series include intrathecal dexamethasone (8, 9), cannabidiol (10, 11), and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (12). Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of these treatments.

There is increasing interest in non-pharmacological treatment of SE in NORSE/FIRES, including Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS), deep brain stimulation (DBS) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). In a recent systematic review (13, 14), 20 patients with NORSE/FIRES treated with neuromodulation were identified. VNS was used in seven patients with cessation of SE in five, although two died. DBS was implanted in four patients (in one VNS first and then DBS), all achieving a good outcome for SE. ECT was performed in 10 patients, of which three were under 4-years-old with a diagnosis of FIRES (13). In 9 out 10 patients SE resolved after 4–8 sessions. Of the 17 patients that survived, 11 had continuing epilepsy, 12 had cognitive and/or motor dysfunction and one patient remained in a vegetative state. In rare cases, dependent on etiology, epilepsy surgery including focal resection may be indicated (15, 16).

Outcomes remain frustratingly poor in children and adults with NORSE/FIRES. Mortality is approximately 12% in children and higher in adults (up to 30%) (5, 6, 17). In a recent prospective study, only 25% of children with FIRES recovered baseline functions compared to 89% of patients with refractory status epilepticus (18). Another long-term follow-up study of 48 adult patients found only 4% of patients made a full neurological recovery (19). In terms of seizure outcomes a recent systematic review (including 280 adult and 587 pediatric cases) found refractory epilepsy persisted in 40% of adults and nearly 60% of children (20). Long-term cognitive data was available in approximately 70% of pediatric cases and up to one third were described as moderately or severely disabled. Overall, the majority of patients did not return to a pre-morbid level of functioning (20).

There is an urgent need to develop pre-clinical models to understand the pathogenesis, and test effectiveness of specific therapies to improve outcomes in this catastrophic and life-changing condition.

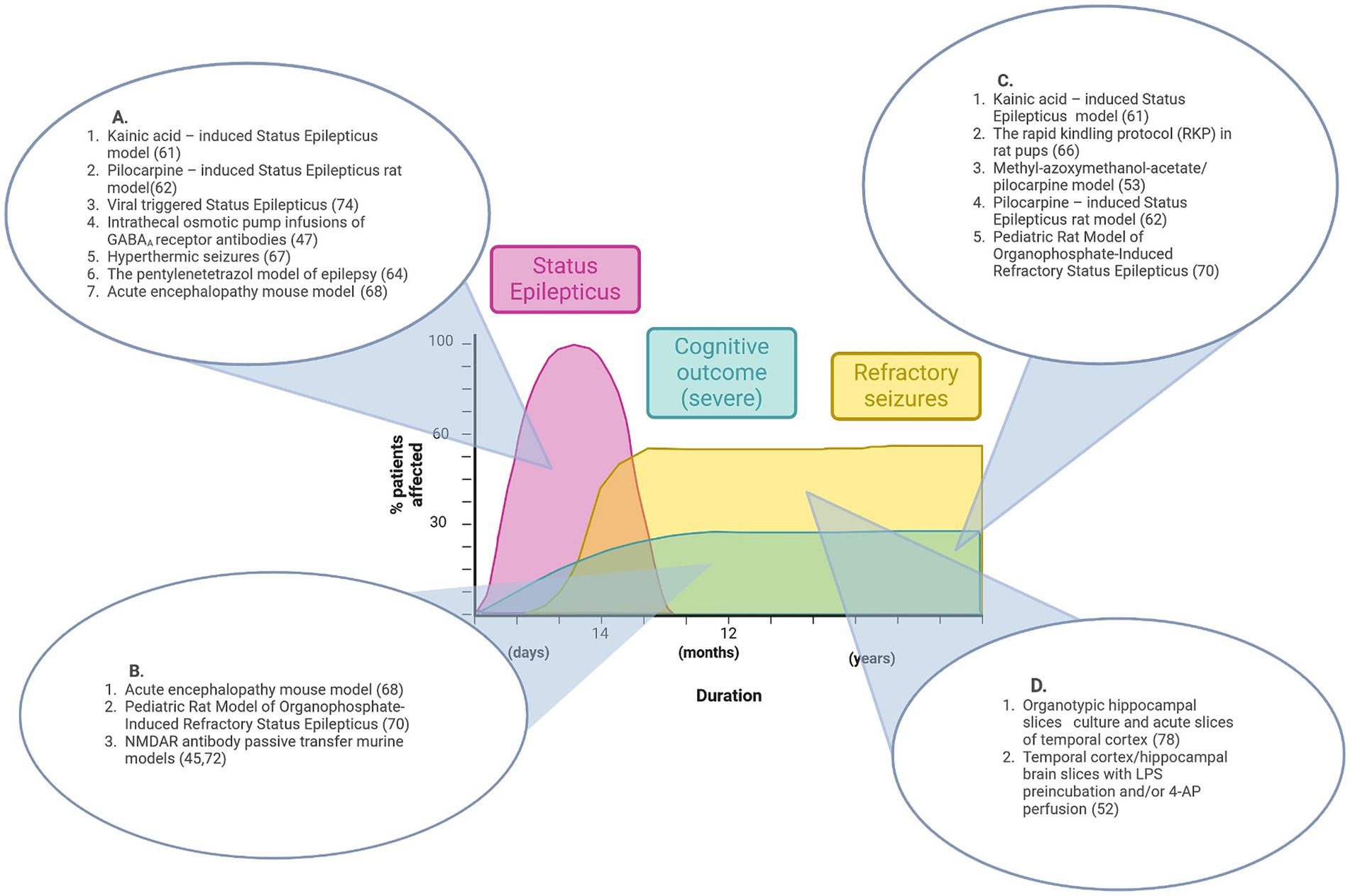

In this review, we examine the potential relevance of existing pre-clinical seizure/epilepsy models and SE study approaches to NORSE/FIRES pathogenesis (Figure 1; Table 1) and propose future research directions.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of features of pre-existing epilepsy animal models that align with disease stages of NORSE/FIRES. No single model recapitulates the full disease course. (A) Animal models that reproduce the acute phase of Status Epilepticus. (B) Animal models that show features of acute seizures and cognitive impairment. (C) Animal models that show features of both refractory seizures and cognitive impairment. (D) Pre-clinical models that demonstrate refractory seizures in vitro. Figure created in Biorender.com.

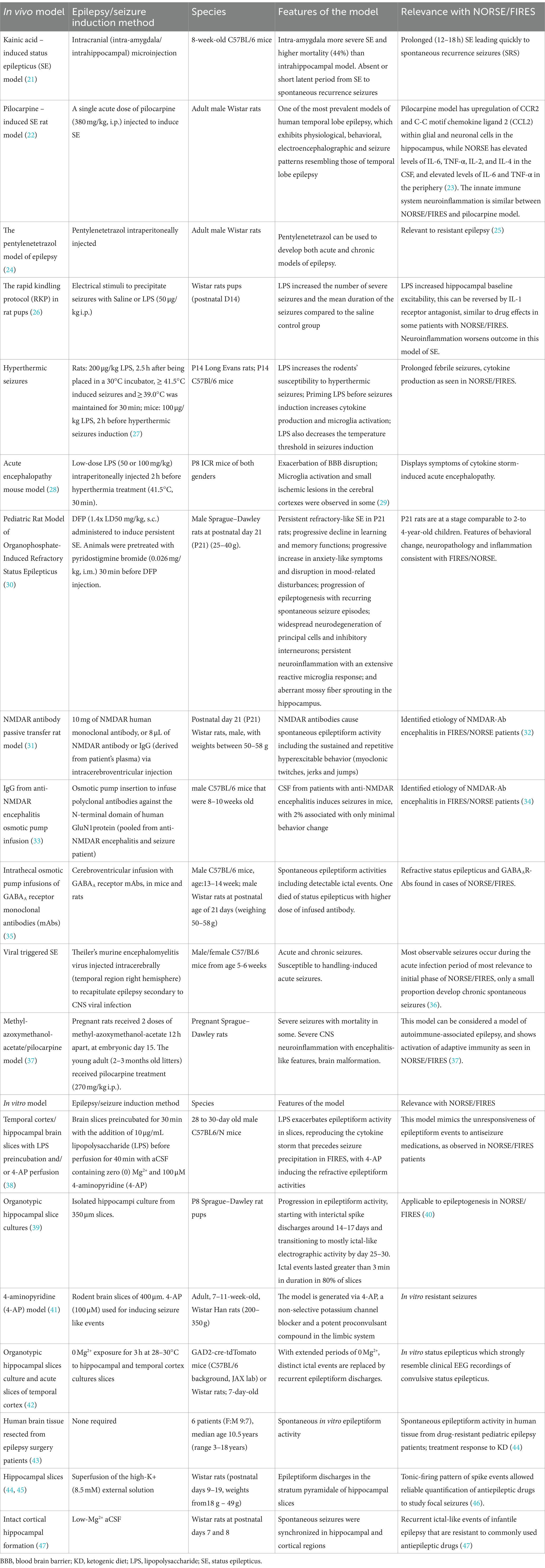

Table 1. This table summarizes in vivo and in vitro seizures models, with specification of species, features, and relevance with NORSE and FIRES for each individual model.

Animal models of SEIn patients, when seizures in SE fails to respond to intravenous antiseizure medications (ASMs) it is termed refractory SE; super-refractory SE (SRSE), as seen in NORSE/FIRES, is defined when SE continues after 24 h or more of anesthetic treatment (48). Frequent EEG analysis is of paramount importance for treatment decisions and prognostication.

When considering animal models of SE, the onset of SE, severity and length varies according to animal strain, sex, age, species, and method of SE induction (49, 50) (Table 1). Quantification of SE severity is primarily based on behavioral assessments using established severity scales [e.g., the Racine scale (51)] not always reflecting underlying ictal EEG changes which are less frequently recorded – in one model it was found that 50% of behavioral seizures did not correspond with underlying epileptiform EEG activity (52–54).

EEG findings in patients with NORSE/FIRES often reveal a pattern of continuous and diffuse slowing, along with focal, multifocal or generalized epileptiform discharges (4, 17). Continuous EEG findings have also been reported (55) and identified common pathognomonic elements. In 6/7 patients a specific seizure pattern of focal faster waveforms, characterized as “sparks,” followed by a gradual appearance of well-formed rhythmic spike/spike and wave complexes was seen. “Ictal shifting” (shifting seizures with contralateral spread) was also described in 4 out of 7 patients (55). Given the significance of EEG in defining and mapping the evolution of SE and NORSE/FIRES, future animal models will need to provide this quantifiable data to ensure validity.

Recent work on EEG abnormalities in immune-mediated seizures has shown that computational models can explain observed EEG abnormalities and help identify putative pathophysiological mechanisms (56, 57). Dynamic Causal Modelling (DCM) of EEG data is an example of this computational approach that allows researchers to model the connectivity and interactions between brain regions, linking the physiology of integrated cortical circuits and their underlying synaptic constraints. DCM uses state-of-the-art Bayesian model inversion techniques to create in silico models that can be used to interrogate synaptic parameters that underlie specific dynamic brain states (58). In recent studies (56, 59), patient EEG recordings, in vivo animal experimental data, and in silico computational models have been combined to provide novel insights into the pathophysiology of immune-mediated epileptogenicity. In the context of NORSE/FIRES, such computational EEG approaches combining relevant pre-clinical model and patient data could be instrumental in identifying microscopic changes in the cortex that initiate seizure resistance and persistence phenotypical of NORSE/FIRES.

In NORSE/FIRES patients the most common neuropathology findings include neuronal loss, microglial activation and reactive gliosis (60, 61); 90% of children show brain abnormalities in long-term follow-up MRI scans, most commonly brain atrophy (74%, generalized in 58%) (62, 63). Given that many chemically or electrically-induced SE animal models go on to develop similar neuropathological changes following SE induction alongside chronic drug-resistant epilepsy and cognitive deficits, studying these long-term effects of NORSE/FIRES may be the most promising and relevant use of these models (64–66).

Animal models of immune-mediated epilepsy and seizuresSerum and CSF studies for neuronal autoantibodies are the most commonly performed diagnostic examination after infection work-up in NORSE/FIRES cases (120/907; 61%) (32). Antibodies identified include anti-MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte protein), anti-NMDAR (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor) antibodies, paraneoplastic and non-paraneoplastic (17, 32, 67–69). In adults with symptomatic NORSE autoimmune encephalitis is the most commonly identified cause (32). Previous studies in autoimmune encephalitis models have successfully used CSF and other human-derived samples to recapitulate core features of the disease including behavioral change, cognitive deficits and seizures (31, 70, 71). More recently, rodent models of immune-mediated seizures in the context of autoimmune encephalitis have also been developed proving the direct epileptogenicity of antigen-specific antibodies (e.g., to the NMDAR, GABAAR (gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor) and LGI1 (leucine-rich glioma inactivated 1) protein) (31, 35, 70). Unlike NORSE/FIRES, status epilepticus was not frequently seen and seizures resolve after completion of intracerebroventricular antibody infusion. This passive transfer approach may be challenging for establishing causality in NORSE/FIRES with no universal specific biomarker (72). However, if seizures were to occur on intracerebral application of CSF from NORSE/FIRES patients this may support the hypothesis of epileptogenic molecules being present in the human-derived samples, particularly as in a recent study pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines [e.g., IL-6 (interleukin-6), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha), IL-8 (interleukin-8), CCL2 (C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2), MIP-1α (macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha), and IL-12p70 (interleukin 12p70)] in serum and CSF were found to be significantly increased in patients with SE compared with control patients without SE. In a subset analysis comparing cryptogenic NORSE patients (n = 51) and those with a known etiology for refractory SE (n = 47), only serum innate immunity pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (CXCL8, CCL2 and MIP-1α) were significantly higher. Elevated innate immunity serum and CSF cytokine/chemokine levels in patients with NORSE were associated with worse outcomes at discharge and at several months after cessation of SE (73). It is important to note that in patients with increased CSF innate immunity cytokines, serial measurements frequently showed normalization of the values within days, and it is unclear if this is associated with immunomodulatory treatment. Further studies are needed with collection of acute and chronic CSF/serum samples and accurate documentation of immunotherapy and seizure frequency to establish cause and effect with respect to these immune mediators in NORSE/FIRES (67).

In animal models the activation and role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of status epilepticus has been shown in pre-clinical models and recently comprehensively reviewed by Vezzani et al. (74). In brief, there is strong evidence that neuronal cells release pro-inflammatory molecules after SE onset that initiate neuroinflammatory changes further influencing neuronal excitability and excitotoxicity (75). The fact that these changes are seen in normal rodent brains after SE induction is relevant to NORSE/FIRES and encouraging that anti-inflammatory treatments alter the progression to chronic epilepsy. A recently described in vitro model of FIRES using rodent brain slices and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce inflammation demonstrated increased mRNA levels of relevant cytokines and inhibition of ictal activity with two specific immunomodulatory drugs, however the relatively acute time course of SE in vitro before treatment (10 min) and pre-incubation with these drugs may limit the translatability of the results to the clinical scenario (38).

Neuropathological findings in NORSE/FIRES also include perivascular T-cell infiltration, i.e., further involvement of the adaptive immune system beyond neuronal autoantibodies (60). A recent study highlighted the marginal involvement of adaptive immunity in the classical model of pilocarpine-induced epilepsy in normal rats when compared to their MethylAzoxyMethanol (MAM)/pilocarpine (MP) model that display malformed brains, status epilepticus and subsequent spontaneous recurrent seizures (37). This model of CNS autoimmune-associated epilepsy has potential to provide crucial insights into the complexities of the acute and chronic neuroimmunological response in NORSE/FIRES and the role of disease-modifying treatments.

Further work is needed to translate all these pre-clinical findings to NORSE/FIRES patients, specifically: the causal role of immune system mediators, identifying the optimal time in SE for immunodulatory intervention and if this intervention should be targeted to the innate and/or adaptive system.

Genetic epilepsy modelsIn a recent systematic retrospective analysis of FIRES patients, genetic testing performed in 23 of 25 patients was non-diagnostic. Interestingly, when a broader cohort of 959 individuals with RSE was analyzed, the highest proportion of individuals with genetic RSE had onset within the first 3 months of life, whereas individuals with FIRES typically have onset in later childhood, with an age of onset ranging from 7.6 months to 18.7 years (69). Similar negative findings for a genetic etiology have been reported in previous studies (76, 77).

This lack of a single causative gene in NORSE/FIRES may hinder the development of a genetic epilepsy model but genetic therapy designed to suppress seizure activity, for example by modulating a specific channel (78), may be considered as a therapeutic approach that could be tested in pre-clinical models (79).

Human brain tissue and epilepsy modelsHuman brain tissue is an invaluable resource that is being increasingly used in neuroscience research of direct relevance to NORSE/FIRES. For example, donated human tissue samples from pediatric epilepsy patients undergoing surgery have been used to demonstrate the therapeutic effectiveness of neurosteroids and decanoic acid, a major medium-chain fatty acid provided in the medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diet, in in vitro electrophysiology studies (31, 43). Recent recommendations to integrate human tissue-based in vitro models into pre-clinical studies to develop anti-seizure therapies will benefit NORSE/FIRES research (44).

Using CSF and brain tissue samples, further insights into underlying immunopathology can be gained from single cell genomics as shown in pediatric epilepsy patients. Kumar et al., found in a study using samples from 6 pediatric epilepsy patients a pro-inflammatory microenvironment in the resected tissue, with extensive activation of microglia and infiltration of other pro-inflammatory immune cells (80). Of particular interest was clear demonstration of a direct interaction between T cells and microglia inside epileptic brain tissue similar to multiple sclerosis. One must caveat these findings with the knowledge that not all the transcriptional-level information will be translated to the protein level. Further validation is required before direct translation to management but nevertheless this advanced genomic analysis should be used in NORSE/FIRES to potentially identify relevant subpopulations of aberrant inflammatory and/or neuronal cells to investigate for pathogenicity.

To maximize the opportunities these rare samples can provide for research and increased understanding of NORSE/FIRES disease pathogenesis it is imperative that standardized procedures for specimen collection and biobanking are followed (67).

Figure 1 summarizes the contribution that existing pre-clinical epilepsy and seizure models could make to the understanding of NORSE/FIRES pathophysiology while also highlighting the research gap for a model that recapitulates the full clinical phenotype.

Discussion and call to actionNORSE/FIRES is a devastating clinical syndrome characterized by acute intractable seizures evolving to treatment-resistant super-refractory status epilepticus, and mostly inevitable adverse cognitive impact in the long-term survivors. There is increasing worldwide collaboration in terms of disease definition, treatment guidelines and establishment of biorepositories underpinned by the unwavering support of dedicated affected family member advocates, parents, guardians, and carers. The role of an aberrant immune system response appears to be gaining evidence in terms of underlying pathophysiology and possible treatments. However, most of the published studies, case-reports and case series are comprised of small patient numbers and often retrospective in nature making it difficult to estimate treatment efficacy in the wider population. In this review we have highlighted how we can use existing pre-clinical models and human-derived samples to further NORSE/FIRES understanding as well as identifying promising future research areas. We call for experts from neurology, neurophysiology, computational biology, genetics, neuroscience, and immunology to collaborate and drive these promising areas of research forward to improve outcomes for affected patients.

Author contributionsDC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. SW was funded through Wellcome Trust Fellowship DC and XZ supported by Epilepsy Research Institute Endeavor Project grant.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References1. Wilder-Smith, E, Lim, E, Teoh, H, Sharma, V, Tan, J, Chan, B, et al. The NORSE (new-onset refractory status epilepticus) syndrome: defining a disease entity. Annals-Academy Med Singapore. (2005) 34:417.

2. Wickstrom, R, Taraschenko, O, Dilena, R, Payne, ET, Specchio, N, Nabbout, R, et al. International consensus recommendations for management of new onset refractory status epilepticus including febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome: statements and supporting evidence. Epilepsia. (2022) 63:2840–64. doi: 10.1111/epi.17397

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. van Baalen, A, Häusler, M, Boor, R, Rohr, A, Sperner, J, Kurlemann, G, et al. Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): a nonencephalitic encephalopathy in childhood. Epilepsia. (2010) 51:1323–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02535.x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Hirsch, LJ, Gaspard, N, van Baalen, A, Nabbout, R, Demeret, S, Loddenkemper, T, et al. Proposed consensus definitions for new-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), and related conditions. Epilepsia. (2018) 59:739–44. doi: 10.1111/epi.14016

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Tharmaraja, T, Ho, JSY, Neligan, A, and Rajakulendran, S. The etiology and mortality of new-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. (2023) 64:1113–24. doi: 10.1111/epi.17523

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Gaspard, N, Foreman, BP, Alvarez, V, Cabrera Kang, C, Probasco, JC, Jongeling, AC, et al. New-onset refractory status epilepticus: etiology, clinical features, and outcome. Neurology. (2015) 85:1604–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001940

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Mehta, NP, Sawdy, R, Maloney, K, Overlee, B, Johnson, RK, Howe, CL, et al. Intrathecal dexamethasone in febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome: a case report. Neurol. Clin. Practice. (2023) 13:e200153. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200153

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Horino, A, Kuki, I, Inoue, T, Nukui, M, Okazaki, S, Kawawaki, H, et al. Intrathecal dexamethasone therapy for febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. (2021) 8:645–55. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51308

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Fetta, A, Crotti, E, Campostrini, E, Bergonzini, L, Cesaroni, CA, Conti, F, et al. Cannabidiol in the acute phase of febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). Epilepsia Open. (2023) 8:685–91. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12740

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Gofshteyn, JS, Wilfong, A, Devinsky, O, Bluvstein, J, Charuta, J, Ciliberto, MA, et al. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) in the acute and chronic phases. J Child Neurol. (2017) 32:35–40. doi: 10.1177/0883073816669450

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Goh, Y, Tay, SH, Yeo, LLL, and Rathakrishnan, R. Bridging the gap: tailoring an approach to treatment in febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome. Neurology. (2023) 100:1151–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207068

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Stavropoulos, I, Pak, HL, Alarcon, G, and Valentin, A. Neuromodulation techniques in children with super-refractory status epilepticus. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1527. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13111527

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Mamaril-Davis, J, Vessell, M, Ball, T, Palade, A, Shafer, C, Aguilar-Salinas, P, et al. Combined responsive Neurostimulation and focal resection for super refractory status epilepticus: a systematic review and illustrative case report. World Neurosurg. (2022) 167:195–204.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.07.141

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Marashly, A, Lew, S, and Koop, J. Successful surgical management of new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) presenting with gelastic seizures in a 3 year old girl. Epilepsy Behav Case Reports. (2017) 8:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.05.002

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Kramer, U, Chi, CS, Lin, KL, Specchio, N, Sahin, M, Olson, H, et al. Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): pathogenesis, treatment, and outcome: a multicenter study on 77 children. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:1956–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03250.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Sculier, C, Barcia Aguilar, C, Gaspard, N, Gaínza-Lein, M, Sánchez Fernández, I, Amengual-Gual, M, et al. Clinical presentation of new onset refractory status epilepticus in children (the pSERG cohort). Epilepsia. (2021) 62:1629–42. doi: 10.1111/epi.16950

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Costello, DJ, Matthews, E, Aurangzeb, S, Doran, E, Stack, J, Wesselingh, R, et al. Clinical outcomes among initial survivors of cryptogenic new-onset refractory status epilepsy (NORSE). Epilepsia. (2024) 65:1581–8. doi: 10.1111/epi.17950

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Taraschenko, O, Pavuluri, S, Schmidt, CM, Pulluru, YR, and Gupta, N. Seizure burden and neuropsychological outcomes of new-onset refractory status epilepticus: systematic review. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:14. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1095061

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Welzel, L, Schidlitzki, A, Twele, F, Anjum, M, and Loscher, W. A face-to-face comparison of the intra-amygdala and intrahippocampal kainate mouse models of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and their utility for testing novel therapies. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:157–70. doi: 10.1111/epi.16406

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Heysieattalab, S, and Sadeghi, L. Dynamic structural neuroplasticity during and after epileptogenesis in a pilocarpine rat model of epilepsy. Acta Epileptologica. (2021) 3:37. doi: 10.1186/s42494-020-00037-7

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Wesselingh, R, Butzkueven, H, Buzzard, K, Tarlinton, D, O'Brien, TJ, and Monif, M. Seizures in autoimmune encephalitis: kindling the fire. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:1033–44. doi: 10.1111/epi.16515

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Mahmoudi, T, Lorigooini, Z, Rafieian-Kopaei, M, Arabi, M, Rabiei, Z, Bijad, E, et al. Effect of Curcuma zedoaria hydro-alcoholic extract on learning, memory deficits and oxidative damage of brain tissue following seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole in rat. Behav Brain Funct. (2020) 16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12993-020-00169-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Singh, T, Mishra, A, and Goel, RK. PTZ kindling model for epileptogenesis, refractory epilepsy, and associated comorbidities: relevance and reliability. Metab Brain Dis. (2021) 36:1573–90. doi: 10.1007/s11011-021-00823-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Auvin, S, Shin, D, Mazarati, A, and Sankar, R. Inflammation induced by LPS enhances epileptogenesis in immature rat and may be partially reversed by IL1RA. Epilepsia. (2010) 51:34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02606.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Kurata, H, Saito, K, Kawashima, F, Ikenari, T, Oguri, M, Saito, Y, et al. Developing a mouse model of acute encephalopathy using low-dose lipopolysaccharide injection and hyperthermia treatment. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). (2019) 244:743–51. doi: 10.1177/1535370219846497

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Koh, S, Dupuis, N, and Auvin, S. Ketogenic diet and Neuroinflammation. Epilepsy Res. (2020) 167:106454. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106454

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Singh, T, Ramakrishnan, S, Wu, X, and Reddy, DS. A pediatric rat model of organophosphate-induced refractory status epilepticus: characterization of long-term epileptic seizure activity, neurologic dysfunction and neurodegeneration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2024) 388:416–31. doi: 10.1124/jpet.123.001794

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Wright, SK, Rosch, RE, Wilson, MA, Upadhya, MA, Dhangar, DR, Clarke-Bland, C, et al. Multimodal electrophysiological analyses reveal that reduced synaptic excitatory neurotransmission underlies seizures in a model of NMDAR antibody-mediated encephalitis. Commun. Biol. (2021) 4:1106. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02635-8

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Lattanzi, S, Leitinger, M, Rocchi, C, Salvemini, S, Matricardi, S, Brigo, F, et al. Unraveling the enigma of new-onset refractory status epilepticus: a systematic review of aetiologies. Eur J Neurol. (2022) 29:626–47. doi: 10.1111/ene.15149

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Taraschenko, O, Fox, HS, Pittock, SJ, Zekeridou, A, Gafurova, M, Eldridge, E, et al. A mouse model of seizures in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Epilepsia. (2019) 60:452–63. doi: 10.1111/epi.14662

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Vogrig, A, Gigli, GL, Nilo, A, Pauletto, G, and Seizures, VM. Epilepsy, and NORSE secondary to autoimmune encephalitis: a practical guide for clinicians. Biomedicines. (2022) 11:44. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11010044

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Kreye, J, Wright, SK, van Casteren, A, Stoffler, L, Machule, ML, Reincke, SM, et al. Encephalitis patient-derived monoclonal GABAA receptor antibodies cause epileptic seizures. J Exp Med. (2021) 218. doi: 10.1084/jem.20210012

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Batot, G, Metcalf, CS, Bell, LA, Pauletti, A, Wilcox, KS, and Bröer, S. A model for epilepsy of infectious etiology using theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. JoVE. (2022) 184:e63673. doi: 10.3791/63673

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Costanza, M, Ciotti, A, Consonni, A, Cipelletti, B, Cattalini, A, Cagnoli, C, et al. CNS autoimmune response in the MAM/pilocarpine rat model of epileptogenic cortical malformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2024) 121:e2319607121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2319607121

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Cerovic, M, Di Nunzio, M, Craparotta, I, and Vezzani, A. An in vitro model of drug-resistant seizures for selecting clinically effective antiseizure medications in febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1129138. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1129138

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen, J, Berdichevsky, Y, Swiercz, W, Sabolek, H, and Staley, KJ. Interictal spikes precede ictal discharges in an organotypic hippocampal slice culture model of epileptogenesis. J Clin Neurophysiol. (2010) 27:418–24. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181fe0709

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Wong, M . Epilepsy in a dish: an in vitro model of Epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Curr. (2011) 11:153–4. doi: 10.5698/1535-7511-11.5.153

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Heuzeroth, H, Wawra, M, Fidzinski, P, Dag, R, and Holtkamp, M. The 4-Aminopyridine model of acute Seizures in vitro elucidates efficacy of new antiepileptic drugs. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:677. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00677

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Burman, RJ, Selfe, JS, Lee, JH, van den Berg, M, Calin, A, Codadu, NK, et al. Excitatory GABAergic signalling is associated with benzodiazepine resistance in status epilepticus. Brain. (2019) 142:3482–501. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz283

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Wright, SK, Wilson, MA, Walsh, R, Lo, WB, Mundil, N, Agrawal, S, et al. Abolishing spontaneous epileptiform activity in human brain tissue through AMPA receptor inhibition. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2020) 7:883–90. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51030

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Morris, G, Avoli, M, Bernard, C, Connor, K, de Curtis, M, Dulla, CG, et al. Can in vitro studies aid in the development and use of antiseizure therapies? A report of the ILAE/AES joint translational task force. Epilepsia. (2023) 64:2571–85. doi: 10.1111/epi.17744

留言 (0)