Established in 2011, the Precision Medicine Program (PMP) at the University of Florida Health (UF Health) initially focused on integrating pharmacogenomics (PGx) into routine clinical practice (Johnson et al., 2013). The program adopted a comprehensive system-wide approach, including the generation of written consult notes by PGx pharmacists (pharmacist with specialized training in PGx) for providers ordering PGx tests or requiring assistance with result interpretation. These consult notes, disseminated through the EPIC® electronic medical record (EMR) as clinical progress notes, have been instrumental in facilitating communication and collaboration.

The PMP PGx pharmacists utilize electronic means to inform ordering providers about the availability of consultation documents. Since its inception, the PMP clinical service has delivered 1970 consultation notes to 160 providers, catering to both clinical and research needs. Despite being designed for prescribers, no formal usability assessment has been conducted on these consult notes to enhance their effectiveness. Furthermore, guidance and literature reviews on PGx consult notes are limited, with the INGENIOUS trial (Eadon et al., 2016) (2016) being one of the few studies addressing concerns related to PGx consult notes. Notably, the trial highlighted issues such as information overload and the potential for overwhelming providers with PGx information. Recognizing the necessity of a formal assessment, it is essential to leverage provider feedback to gauge satisfaction and the efficacy of documentation. Without such evaluation, the success of pharmacogenomic implementation may be impeded. Usability research, focusing on the user experience (UX) by deeply understanding users’ needs, values, abilities, and limitations, emerges as a valuable tool to analyze provider feedback (Rosala; Yen and Bakken, 2011; Elchynski et al., 2021). This research can contribute to the enhancement of the entire PGx consultation process by informing the optimal content and format of PGx consult notes and fostering a better understanding of PGx. In pursuit of optimizing the usability of consult notes, our objective is to capture the perspective of provider needs, enhance the current content of PGx consult notes at UF Health, and guide future developments in PGx documentation.

2 Materials and methods2.1 Study settingThe research was carried out at UF Health Shands Hospital, a substantial learning health system that utilizes EPIC® as its electronic medical record (EMR). The implementation of PGx consult documentation within the hospital is led by the UF Health Precision Medicine Program (Johnson et al., 2013), a team primarily comprised of PGx specialist pharmacists. All procedures were developed in alignment with the clinical consult notes used at the initiation of the study. Approval for the study was granted by the University of Florida Health Quality Improvement Project Registry.

2.2 Participant recruitmentEach participant was invited via email to participate in our in-depth user sessions (1-3 participants per session). We recruited UF Health clinicians who had previously ordered PGx testing and been the recipient of a PGx results interpretation (using a report generated from PGx clinical decision support alerts). Each session was moderated by either a PGx pharmacy resident or a pharmacy student and lasted between 30 and 60 min. Each participant verbally consented prior to the session through a secure online video chat.

2.3 Moderator guide developmentA standardized moderation guide (see supplemental document A) was collaboratively developed by a team comprising two PGx residents, a PGx pharmacist, an informatics pharmacist, and two pharmacy students. The guide was designed for use with PGx consult notes from UF Health. In our study, we sought feedback on the logic of the consult note to help improve the content and format of PGx consultation. Our PGx clinical service typically employs the SOAP format (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan), a widely adopted format across healthcare systems (Pearce et al., 2016). We called this format “traditional format”. In contrast, a flipped format, wherein the PGx test results and interpretation are positioned at the top of the note—an alternative format option preferred by the participants. At the time of study, both formats were implemented in clinical practice. Two sample notes (see supplemental document B) were incorporated into the moderation guide. Importantly, these notes were extracted from genuine patient PGx consult notes, ensuring compliance with HIPAA regulations by removing all patient identifiers. The flipped note illustrates a sample patient with a gastrointestinal case.

2.4 In-depth user sessionsEach sessions were led by 1-2 moderators and were recorded with the participants’ prior consent. Before each session, participants were sent a modified Computer System Usability Questionnaire (CSUQ) (Lewis, 2018), a validated computer usability satisfaction questionnaire via REDCap® survey (UF Redcap, Nashville, TN). The CSUQ survey sought clinicians’ assessments of the current PGx consult note across various characteristics. We combined and presented data in seven categories: organization, ease of comprehension, information quality, clarity of the future medication and phenoconversion section, helpfulness, and overall satisfaction. We modified the questionnaire to replace “this system” by “this note” or “phenoconversion session” to improve the clarity of survey questions. Providers were presented with a set of statements and asked to express their opinions on each, ranging from strongly disagree to agree for each statement (Lewis, 2018). Additionally, the survey gathered information about participant demographics, their experience with EPIC® EHR, and reflections on their knowledge of PGx.

During the sessions, participants were introduced to a set of two sample PGx consult notes, representing different clinical scenarios while adhering to the existing content and format. They were given a few minutes to familiarize themselves with each consult note. The moderator then initiated a series of predetermined and impromptu questions through a standardized script (see supplemental document A) to assess the participants’ ease of comprehension and application of pharmacogenomic information. The questions also delved into the appropriateness of specific sections’ presence and placement, such as relevant laboratory markers and the patient’s past medication list. This approach was employed to ensure consistency across sessions and maintain a structured exploration of participants’ perspectives.

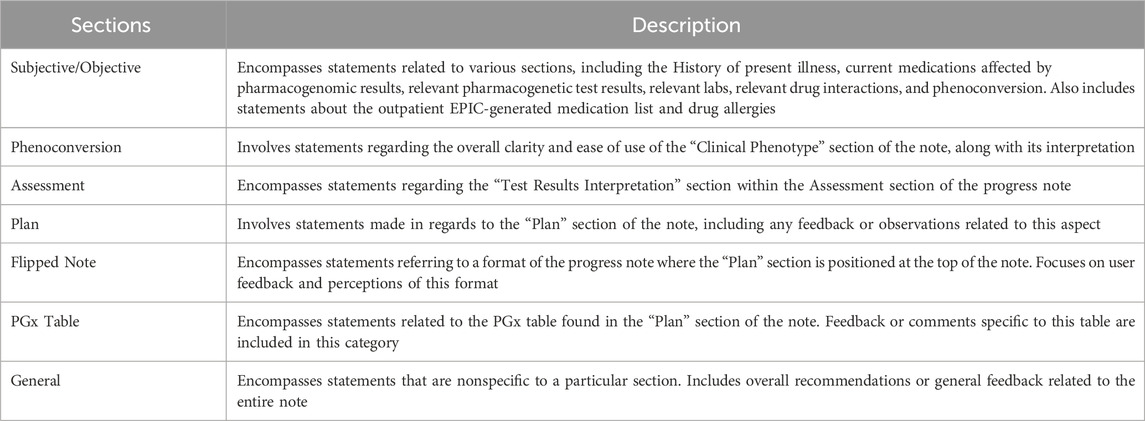

2.5 Data collection and outcome measuresData from the in-depth user sessions were captured using Zoom® (2022 version, San Jose CA) video and audio recordings. Zoom® video recordings allow for both the participant and the moderator’s monitor display to be recorded. The recordings were then transcribed using the transcribing software Grain® (2021 version, San Francisco CA) and reviewed independently by two analysts (ND and NR) to extract suitable content for analysis. Three analysts (ND, BH, NR) and one pharmacogenomic specialist (EE) analyzed the first three sessions and codified the data to establish common themes, utilizing the qualitative data analysis software Nvivo® (v11 plus, Denver CO). Our thematic analysis focused on specific sections of the consultation note (subjective, phenoconversion, assessment, plan, PGx table, flipped note concept, and general idea), reflecting the structure of the in-depth sessions. Table 1 provides definitions for each section. We evaluated each section based on strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions for improvement. After establishing common themes, multiple analysts independently reviewed each session. Disputes were resolved by a team of four analysts and a PGx specialist. To ensure rigor, at least three individuals reviewed each session. Finally, CSUQ data were presented quantitatively as mean, median and interquartile range.

Table 1. Main description of each section used for analysis.

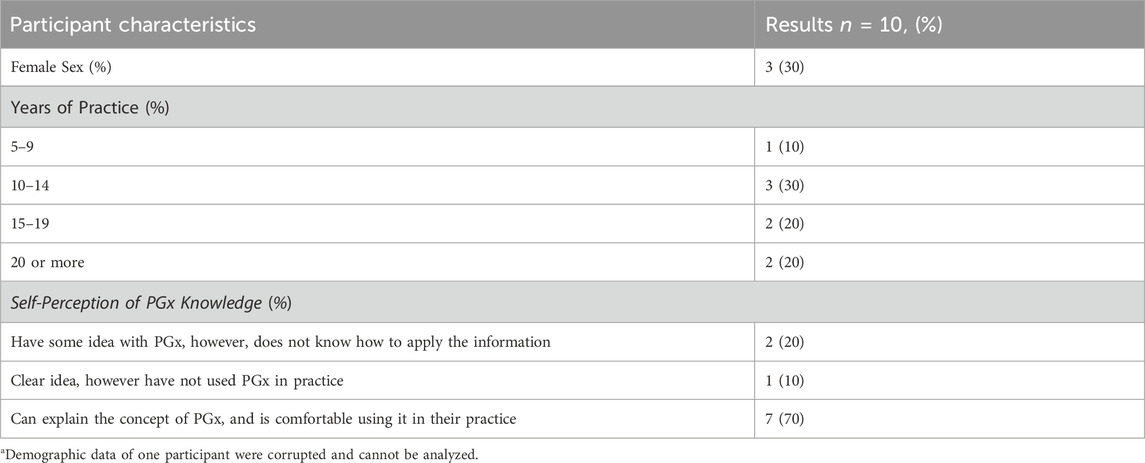

3 ResultsTable 2 displays the demographics of the study participants as well as their initial assessment with PGx knowlege. We sent out invitations to 79 potential participants between January 2022 and February 2022. Eleven providers were recruited and interviewed for the study (response rate 15%), but only 10 participants were included in the demographics analysis due to a data error (unretrievable) in one participant’s information. Data from this participant was still included by the rest of the analysis. Among the participants, three providers had a practice experience ranging from 10 to 14 years, while two providers had practiced for 20 years or more.

Table 2. Participant Demographics. Characteristics of the ten providers who participated in the in-depth user sessions.

Regarding participants’ knowledge of PGx, the majority of providers (70%) expressed that they are comfortable applying their knowledge of PGx in their practice. Additionally, 20% stated that they had a conceptual understanding of the idea but faced challenges in applying the information.

The CSUQ survey findings revealed that four out of ten providers strongly agreed with the statement indicating satisfaction with the note’s organization. On the other hand, six out of ten providers neither agreed nor disagreed regarding the clarity of the phenoconversion section, suggesting a potential opportunity for redesigning this specific section to enhance understanding and user experience (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. CSQU satisfaction data (1: strongly disagree, 5: strongly agree).

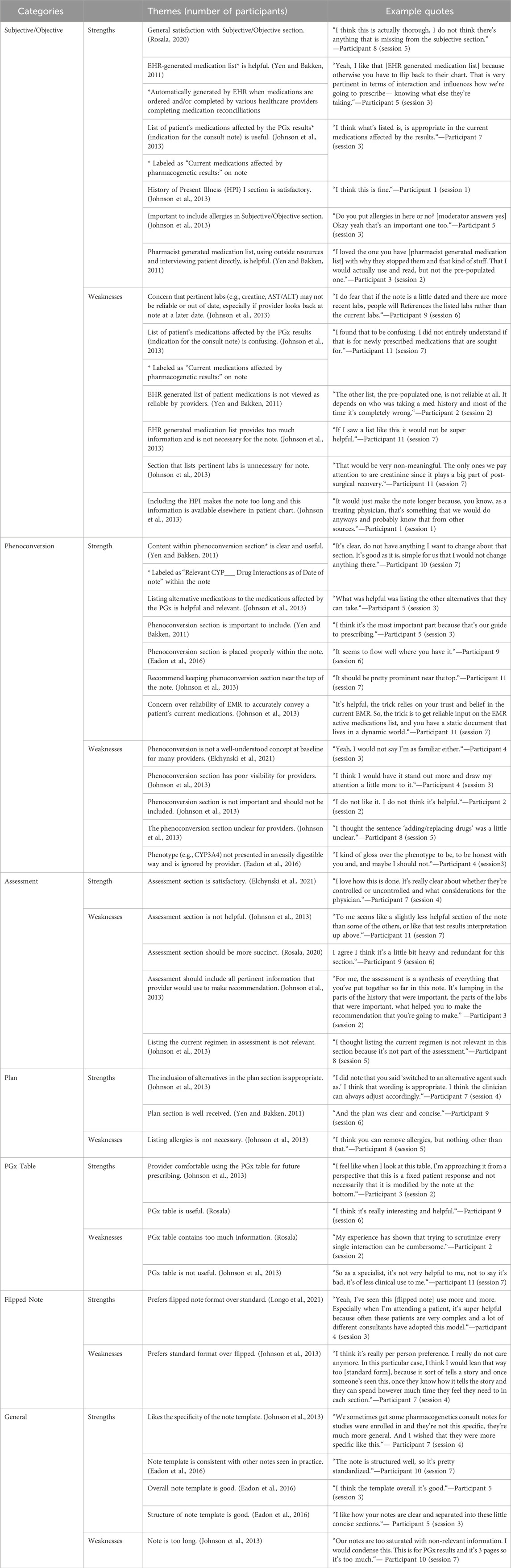

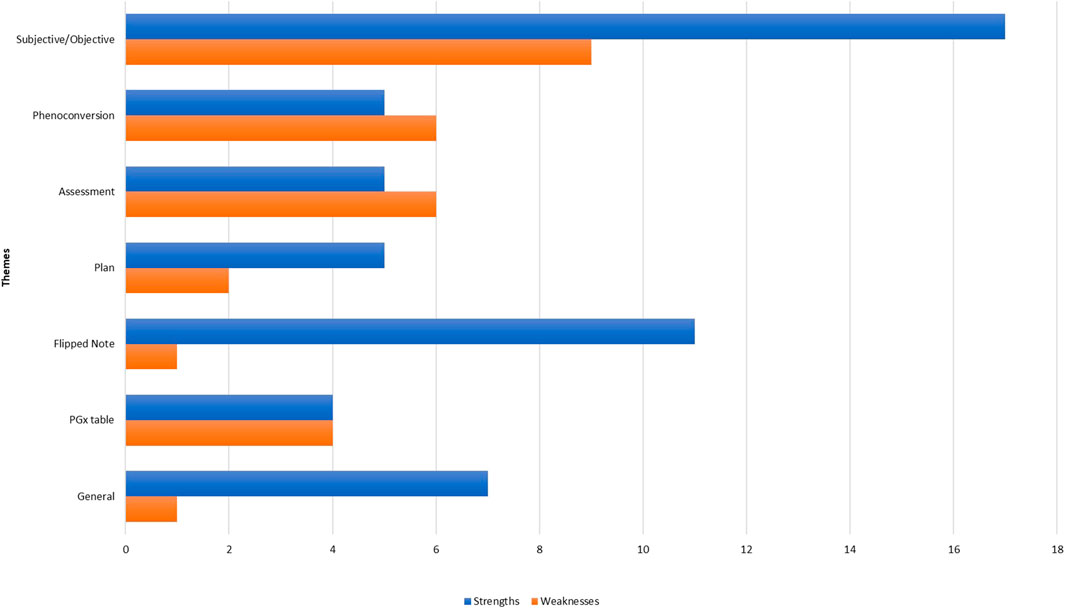

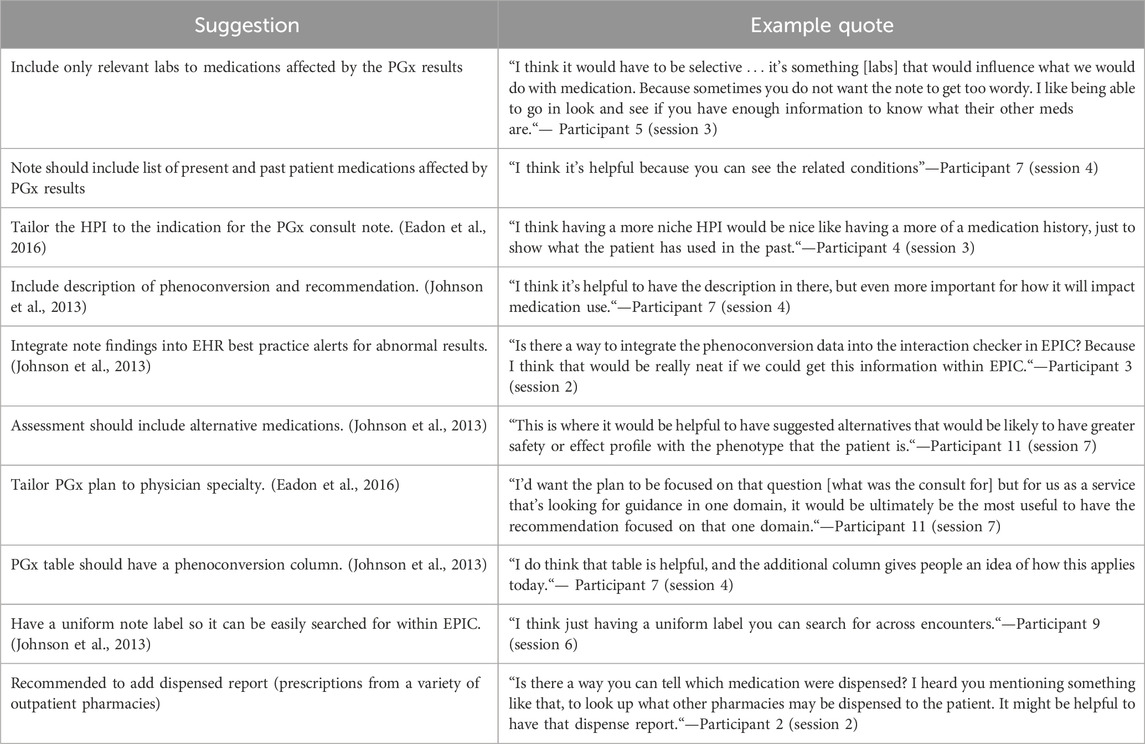

Table 3 presents key themes and illustrative quotes extracted from the in-depth user interviews. It highlights strengths and weaknesses identified within each section of the consult note. Figure 2 quantifies participant feedback for each consult note section. Table 4 compiles significant suggestions from participants to improve the PGx consultation note’s design. Below is a summary of the main information collected for each section.

Table 3. Main themes and example quotes from participants.

Figure 2. Quantifying participant comments based on type and appropriate section of the consult note.

Table 4. Major suggestions for improvement from participants.

3.1 Subjective/objective sectionWhile participants expressed overall satisfaction with the section’s content, they provided valuable suggestions for enhancing the included information. Notably, in the History of Present Illness (HPI) section, Participant one suggested the importance of including the reason for the physician’s test request—an idea echoed by all sessions. Additionally, some providers expressed a preference for a more detailed HPI and an extensive medication history to showcase past patient use (Participant 4).

Our note incorporates both a pre-populated list from the Electronic Health Record (EHR) and a past medication list compiled by PGx pharmacists from patient information and external medication records. Participants unanimously found the pre-populated lists unreliable and strongly favored those generated by the pharmacist, particularly since the note encompasses both current and past medications.

Regarding the inclusion of laboratory information and genotype details, most providers disagreed, citing their availability in the EHR for review (Participant 8). Alternatively, some favored the inclusion of only pertinent labs to prevent the note from becoming overly verbose (Participant 5). Finally, there was a divergence of opinions on including allergies in the note. Two providers in session three emphasized the importance of listing patient allergies in this section, while two participants in session four argued that including allergies is unnecessary due to existing chart information and proposed its removal to streamline the note.

3.2 PhenoconversionPhenoconversion, defined as the ability of external factors, such as drug-drug-interaction, to modify a predicted phenotypic expression base on genotype, is a crucial aspect (Shah and Smith, 2015; Klomp et al., 2020; Cicali et al., 2021). Although the clarity of content in this section was acknowledged, many participants were unfamiliar with the term “phenoconversion”, wf which was not explicitly mentioned in the note but surfaced during discussions. Several participants considered the information in this section paramount, emphasizing their tendency to immediately explore recommendations for potential medication changes based on the results (Participant 4). Ten out of the eleven participants found this information beneficial, with suggestions to enhance its visibility, such as making it stand out more or potentially segregating it into its own section (Participant 4).

While some participants felt that the phenoconversion information might be better placed in the assessment section, a few did not mind its repetition in several locations of the consult note, recognizing its importance to their clinical decision-making. One participant remarked on the insufficient information in this section, and Participant five proposed that listing alternative medications would be helpful for better guidance.

3.3 Flipped noteDuring each user sessions, two note formats were presented to participants, and their preferences were assessed. The flipped note format was favored by the majority, with ten out of eleven participants expressing a preference for it, while one participant remained neutral. The prevailing sentiment among participants was that the flipped note format is preferable due to its ability to prominently display essential information. Participant 11 highlighted its efficiency, stating that it is “really helpful because you’re cutting right to the chase,” especially in complex cases involving multiple consultants.

However, there was a dissenting opinion, as one participant preferred the standard format, citing its contribution to the logical flow of the patient’s story. Participant seven noted, “it is really a person preference. In this particular case, I think I would lean that way too [standard form], because it sort of tells a story.” The diverse preferences underscored the subjective nature of individual preferences in note formats, with some favoring efficiency and directness while others valued a narrative structure.

3.4 Assessment sectionA significant critique of the assessment section was to improve the conciseness, with providers expressing that it was “a little bit heavy and redundant for this section” (participant 9) and that it “did not feel like it is an assessment and it felt like a history instead” (Participant 3). Participants favored familiar terms such as “well controlled or poorly controlled” and advocated for brevity, suggesting that the assessment should use as few terms as possible while still effectively summarizing the information from preceding sections. Additionally, participants recommended tailoring the assessment to the specific medication that prompted the consult and including only pertinent labs for a more streamlined and relevant summary.

3.5 Plan sectionWhile all providers acknowledged the clarity and conciseness of this section, there were varying opinions on its necessity in the note. Some providers believed that this section was not essential, with three expressing the view that pharmacists should refrain from making clinical recommendations within the note. According to Participant 3, they were “looking for specific changes to medications” based on the pharmacogenomic (PGx) results. These providers voiced concerns about patient visibility of these notes, suggesting that PGx notes should primarily present relevant information for physicians to use in their broader clinical decision-making.

Another suggestion that emerged was the idea of tailoring the plan to the specialty of the provider who requested the note. This recommendation aimed at providing a more specialized and relevant plan, catering to the specific needs and context of the requesting healthcare professional.

3.6 PGx tableThe note template concludes with a comprehensive list of other medications categorized by different indications that might be impacted by the patient’s CYP polymorphism. The intention behind this table is to offer providers a reference for future use, providing insights into potential medications affected by the patient’s polymorphisms. However, this table sparked the most discrepancies and differing opinions among the providers.

While seven providers found the table helpful and expressed comfort in using the information for future reference, four providers considered the table to be overly extensive and containing unnecessary details. Although most participants leaned towards a preference for a shorter table, others suggested additional information, such as including a list of alternative agents for each indication and incorporating a phenoconversion column. The diverse perspectives highlighted varying preferences regarding the level of detail and length of the table, emphasizing the need for customization to meet individual provider preferences and information needs.

3.7 GeneralOverall, participants expressed positive feedback regarding the PGx consultation note template’s consistency and alignment with other consultation note formats. This consistency fosters familiarity and ease of use within the broader EHR system. However, participants strongly recommended reducing the note’s length to improve efficiency and streamline information retrieval. Additionally, they emphasized the importance of using consistent titles for each note. This standardization would significantly enhance searchability within the EHR system, allowing clinicians to quickly locate specific PGx consultation notes and access relevant patient information.

4 DiscussionThe implementation of pharmacogenomic (PGx) consultation services has become widespread across many institutions (Eadon et al., 2016; Bain et al., 2018; Longo et al., 2021). However, our study stands out as one of the first to adopt a user-centered approach for a formal assessment of provider needs and design requirements, aiming to guide future enhancements of PGx result notes. This approach allowed us to gain valuable insights into providers’ workflows and preferences regarding PGx information (Andreassen and Malling, 2019). Such knowledge is instrumental for PGx specialists in tailoring consult notes to align with the clinical context, facilitating easy navigation and utilization of relevant information. Several key concepts and ideas emerged from our study, providing valuable insights for institutions looking to implement or refine PGx services (see Table 4).

Responding to requests from specialists familiar with patients who sought a shortcut to the assessment section, we also offered PGx consult notes using the flipped format, where the assessment was presented first. Concerns about redundant information in consult notes have been reported in the literature (Brown et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2018), and our study received mixed comments on note format preferences. While several participants favored the standard SOAP note for its familiarity, others preferred a more concise version using the flipped note. Therefore, we recommend providing consultations using the SOAP format but offering flip notes as an option for providers with specific requests. The SOAP note format, being more traditional, is generally easier for new providers to comprehend. Similarly, for all other sections that receive mixed comments from participants, we compile a list and discuss them with our precision medicine leadership to discuss plan for implementation and prioritization.

Our note template also introduced a new section called phenoconversion, a crucial concept in PGx consult notes that might be overlooked or not fully understood by general healthcare providers. In our study, we identified that 60% of participants did not fully comprehend this concept, indicating a need for redesign for better clarification. We propose including a short description to define phenoconversion, aiding providers in better understanding this section. Additionally, it is essential to separate and clarify the differences between current active drug-gene interactions (DGI) and potential DGIs to prevent confusion. However, capturing the current active medication list for outpatients remains challenging due to current technological limitations which only able to capture medication order information but not medication dispensing records (Lin et al., 2021).

While consultation notes traditionally serve as a direct means of consultation for requested providers, leveraging technology can make information more accessible and extend recommendations to a broader pool of providers. The ability to provide succinct information emerged as a crucial theme in our study, prompting consideration for building a “genomics profile” within patients’ health record systems. The University of Florida Health has recently implemented this approach by incorporating the Epic® Genomics Module. Utilizing technology from this module, we developed language capable of explaining and providing recommendations for each drug-gene interaction relevant to a specific patient profile. This genomics profile consolidates all relevant genetic information onto a single page, facilitating easy access for healthcare providers to make optimal prescribing decisions.

Despite these insights, our study has several limitations. We collected data from a single institution, and while UF Health is a large healthcare system, the workflow and structure may not be universally applicable to other institutions. Furthermore, the use of the Epic® EHR at UF Health might not be representative of other EHR systems. Additionally, our study focused solely on physicians as the main requesters for PGx consult notes, and future research should consider collecting feedback from other healthcare providers, such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants. The use of in-depth user sessions, rather than one-on-one interview to collect feedback may lead to uneven contributions among participants, with some being more vocal than others. Lastly, our recruitment had a low response rate which might create a shwed representation of the target population.

4.1 Future directionsWe plan to enhance the design of currently implemented PGx result note at our institution and disseminate a framework for other institutions who plan to implement PGx result documentation. Once we update the PGx note template, we plan to further evaluate the information provided in our PGx results note and provider satisfaction with the documentation through future provider interview. Ultimately, we will develop a practical design guideline to assist with PGx result documentation development as well as other consultation notes provided by pharmacists.

5 ConclusionUtilizing provider feedback via in-depth user sessions and having providers complete the CSUQ regarding a PGx result note resulted in valuable feedback. The feedback collected will guide changes to the implemented PGx consult note at our institution and help create a standardized PGx consult note format.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributionsND: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. NR: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. BH: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Resources, Writing–review and editing. HA: Data curation, Project administration, Writing–review and editing. LL: Data curation, Project administration, Writing–review and editing. EE: Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. EC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing–review and editing. KW: Resources, Validation, Writing–review and editing. LC: Resources, Validation, Writing–review and editing. KN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award number UL1TR001427.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary materialThe Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2024.1377132/full#supplementary-material

ReferencesAndreassen, P., and Malling, B. (2019). How are formative assessment methods used in the clinical setting? A qualitative study. Int. J. Med. Educ. 10, 208–215. doi:10.5116/ijme.5db3.62e3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bain, K. T., Schwartz, E. J., Knowlton, O. V., Knowlton, C. H., and Turgeon, J. (2018). Implementation of a pharmacist-led pharmacogenomics service for the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PHARM-GENOME-PACE). J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 58 (3), 281–289. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.02.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brown, P. J., Marquard, J. L., Amster, B., Romoser, M., Friderici, J., Goff, S., et al. (2014). What do physicians read (and ignore) in electronic progress notes? Appl. Clin. Inf. 5 (2), 430–444. doi:10.4338/ACI-2014-01-RA-0003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cicali, E. J., Elchynski, A. L., Cook, K. J., Houder, J. T., Thomas, C. D., Smith, D. M., et al. (2021). How to integrate CYP2D6 phenoconversion into clinical pharmacogenetics: a tutorial. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110 (3), 677–687. doi:10.1002/cpt.2354

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Eadon, M., Desta, Z., Levy, K., Decker, B., Pierson, R., Pratt, V., et al. (2016). Implementation of a pharmacogenomics consult service to support the INGENIOUS trial. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 100 (1), 63–66. doi:10.1002/cpt.347

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Elchynski, A. L., Desai, N., D’Silva, D., Hall, B., Marks, Y., Wiisanen, K., et al. (2021). Utilizing a human–computer interaction approach to evaluate the design of current pharmacogenomics clinical decision support. J. Personalized Med. 11 (11), 1227. doi:10.3390/jpm11111227

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, A. E., Hribar, M. R., Goldstein, I. H., Henriksen, B., Lin, W. C., and Chiang, M. F. (2018). Clinical documentation in electronic health record systems: analysis of similarity in progress notes from consecutive outpatient ophthalmology encounters. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 1310–1318.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Johnson, J. A., Elsey, A. R., Clare-Salzler, M. J., Nessl, D., Conlon, M., and Nelson, D. R. (2013). Institutional profile: university of Florida and Shands hospital personalized medicine program: clinical implementation of pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics 14 (7), 723–726. doi:10.2217/pgs.13.59

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Klomp, S. D., Manson, M. L., Guchelaar, H. J., and Swen, J. J. (2020). Phenoconversion of cytochrome P450 metabolism: a systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 9 (9), 2890. doi:10.3390/jcm9092890

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lewis, J. R. J. (2018). IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: psychometric evaluation and instructions for Use1993, 57.

Lin, W. C., Chen, J. S., Kaluzny, J., Chen, A., Chiang, M. F., and Hribar, M. R. (2021). Extraction of active medications and adherence using natural language processing for glaucoma patients. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 773–782.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Longo, C., Rahimzadeh, V., and Bartlett, G. (2021). Communication of Pharmacogenomic test results and treatment plans in pediatric oncology: deliberative stakeholder consultations with parents. BMC Palliat. Care 20 (1), 15. doi:10.1186/s12904-021-00709-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., George, G. S., and Langford, C. A. (2016). The essential SOAP note in an EHR age. Nurse Pract. 41 (2), 29–36. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000476377.35114.d7

留言 (0)