ER is a crucial organelle with a lot of functions, including storage and buffering of calcium ions (Ca2+), lipid biosynthesis, and folding and assembly of secretory and transmembrane proteins (Celik et al., 2023). However, due to physical and chemical factors, cell homeostasis is easy to be destroyed and cellular proteins cannot be properly folded, causing a series of physiological responses, including lack of Ca2+ deficiency, molecular chaperone or cellular energy, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), protein variation and disulfide bond reduction (Oakes and Papa, 2015; Rufo et al., 2017). For maintaining ER homeostasis, cells have developed an adaptation mechanism through a series of adaptive pathways called the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Hetz et al., 2020).

The UPR aims to recover the ER-related protein folding ability by increasing the expression of ER-related chaperones and attenuating global protein translation (Rufo et al., 2017). In mammalian cells, the UPR is controlled by three ER stress sensors, namely, IRE1α, PERK, and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). In homeostasis conditions, these proteins are kept in an inactive state by the master regulator of the UPR, the glucose-regulated protein-78 (GRP78, also known as BiP) (Ernst et al., 2024). PERK protein responds to ER stress by inducing eIF2α phosphorylation, resulting in increased expression of ATF4 protein and CHOP (Saaoud et al., 2024). IRE1α protein cleaves the transcription factor X-box binding protein (XBP1) mRNA to generate a spliced XBP1 variant (XBP1s), which triggers ER stress by up-regulating a large number of genes involved in the UPR (Park et al., 2021). During ER stress, the ATF6 protein is translocated from the ER to the Golgi apparatus for cleavage by S1P and S2P. The cleaved N-terminal region of ATF6 protein is an active transcription factor for ER chaperones and XBP1 (de la Calle et al., 2022).

Immunogenic cell death (ICD) is a subtype of cell death that triggers an adaptive immune response against remaining tumor cells (Aria and Rezaei, 2023; Sprooten et al., 2023). Certain chemo-drugs, radiation therapy, and photodynamic therapy were reported to induce ICD on treated tumor cells by eliciting ER stress and subsequent secretion of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including calreticulin membrane translocation, ATP and HMGB1 release, type-I interferon production, etc. (Galluzzi et al., 2020). These DAMPs then recruit innate immune cells such as dendritic cells to stimulate tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to eliminate remaining tumors. We recently demonstrated that the chemo-drug Mitoxantrone was a bona-fade ICD inducer for prostate cancer by activating eIF2α via PERK/GCN2-dependent ER stress cascade (Li et al., 2020). We also discovered that Alternol, a novel small chemical compound, induced a strong ICD response in prostate cancer via releasing large amounts of inflammatory cytokines while the molecular mechanism was not determined (Li et al., 2021).

Alternol was isolated from the fermentation of a mutant fungus obtained from Taxus brevifolia bark (Liu et al., 2020). Previous studies from our group and others demonstrated that Alternol treatment in prostate cancer cells caused a dramatic increase in reactive oxygen species and subsequent cell death (Tang et al., 2014; Zuo et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020). We also discovered that Alternol interacted with 14 cellular proteins including five mitochondrial and ER-residing chaperone proteins, indicating a potential link between Alternol-induced ICD (inflammatory response) (Li et al., 2021) and ER stress. To determine if Alternol-induced ICD responses were due to chaperone protein disruption and ER stress, we conducted a series of experiments to investigate ER stress-related cascades in Alternol-treatment prostate cancer cells. Our data confirmed that Alternol treatment elicited multiple ER stress cascades and subsequent immunogenic ATP release.

Materials and methodsCell lines, reagents, antibodies, and siRNAHuman prostate cancer C4-2B, 22RV1, PC-3 cells, and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia-1 (BPH1) cells were recently obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and authenticated by ATCC before shipment. Cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) plus 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Antibodies of ATF-3 (#33593), ATF-6 (#65880), IRE1α (#3284), ATF4 (#11815), eIF2α (#9722), eIF2α/pS51 (#9721), CHOP (#2895), BiP (#3177), XBP1s (#27091), PERK (#5683), phospho-PERK (T980, #3179), PARP (#9542), HSP60 (D6F1, #12165), HSPA8 (#8444), HYOU1 (#13452), NF-κB/p65 (#3034), phospho-NF-κB (S563, #3031), I-κBa (#4024), and IKK (#2684) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, United States of America). Antibodies of HSP90B1 (#H9010) and phospho-IRE1α (Ser724) (# PA1-16927) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, United States of America). Antibodies of HSP90A1 (sc-13119) and β-Actin (sc-47778) were obtained from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX, United States of America).

Alternol was obtained as a gift from Sungen Biosciences (Shantou, China). PERK inhibitor AMG44 (#SML3049), and ATF-6 inhibitor CEAPIN-A7 (SML2330) were obtained from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA, United States of America). PKR inhibitor Imoxin (S9668), NF-κB inhibitor SN50 (S6672), and IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 (S8875) were obtained from Sellectchem (Huston, TX, United States of America). ROS scavenger n-acetylcysteine (N-Ac) was obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). The small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for IRE1a, PERK, and PKR were obtained from Horizon Discovery Ltd (Cambridge, UK). ATPlite™ luminescence assay system (catalog #6016941) was purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA).

Western blot assaysWestern blot assay of protein expression was conducted as described (Li et al., 2019). Briefly, total cellular protein lysates were extracted using the radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. An equal amount of proteins was subjected to SDS-PAGE separation, followed by transferring onto the PVDF membrane. After blocking in 5% nonfat milk for 1h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein bands were visualized using the horseradish peroxidase-linked (HRP-linked) secondary antibody for 2 h and the ECL solution (Santa Cruz Biotech).

ATP level assayATP level was measured using ATPlite™ Luminescence Assay System following the manufacturer’s instructions, as described (Li et al., 2021). Briefly, C4-2B or PC-3 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate overnight, and then treated as described. The cell pellets were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer. The cellular lysate was then diluted with the assay buffer, and mixed with the substrate solution (at a 4:1 ratio). The luminescence signal was measured using the Lumat LB9501 reader (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN).

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)Alternol binding with the chaperone proteins was examined using the CETSA assay, as described previously (He et al., 2017). Briefly, C4-2B cells were incubated with Alternol (10 μM) for 2 h. Cell pellets were washed with PBS followed by two repeated freeze-thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen. The lysates were then aliquoted into 9 vials for heating at 37, 41, 45, 49, 53, 57, 61, 65, and 69°C for 3 min, and then cooled down on ice for 2 min. The cell lysates were briefly vortexed and then centrifuged at 18,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel followed by Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysisData were present as the mean ± SEM from at least three experiments. Representative images of non-quantitative data were shown from multiple experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using ANOVA analysis and student t-test to compare two groups with SPSS software (Chicago, IL). A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered as a significant difference.

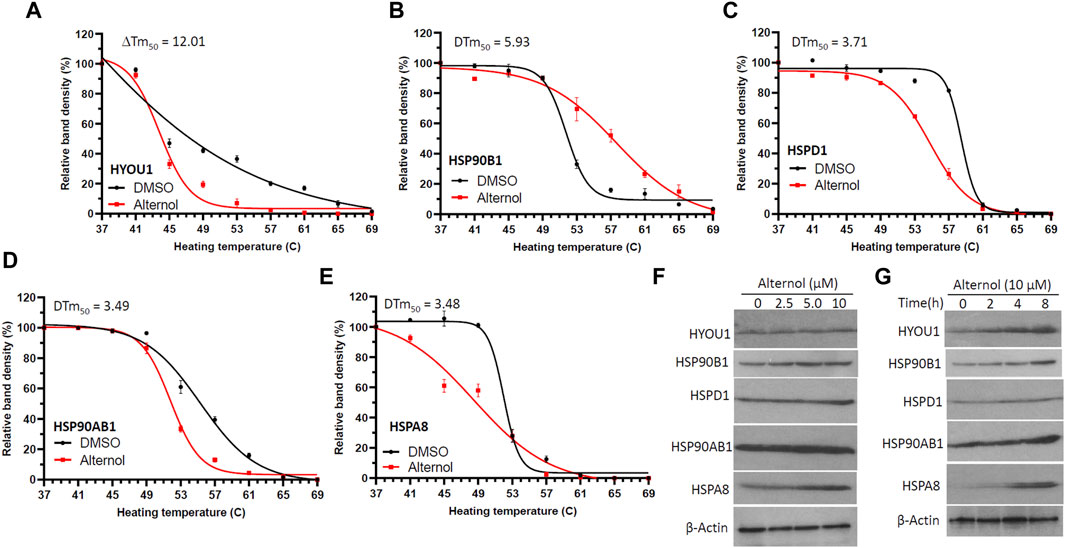

ResultsAlternol interacts with multiple heat-shock proteinsWe and others have shown that Alternol induces oxidative stress-dependent cell death preferentially in malignant cells (Tang et al., 2014; Zuo et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). In our previous report (Li et al., 2019), to identify Alternol-interacting proteins we utilized biotin-labeled Alternol and pulled down 14 cellular proteins. Among these proteins, there were five chaperone proteins, including two ER-residing HYOU1 (also known as HSP120α or GRP170) and HSP90B1 (or GRP94), mitochondrial HSPD1 (or HSP60), cytosolic HSP90AB1 (or HSP84) and heat-shock cognate HSPA8 (HSC70). To further verify their interaction with Alternol, we conducted a CETSA assay (Martinez Molina et al., 2013) in prostate cancer PC-3 cells. As shown in Figures 1A–E, these proteins displayed a clear curve-shifting pattern after Alternol treatment with a ΔTm50 value between 3.48C and 12.01C. These data indicated that Alternol interacted with these proteins in cells. In addition, Alternol treatment increased the expression levels of HYOU1, HSP90B1, HSP90AB1, and HSPA8 proteins (Figures 3F, G). Since these chaperone proteins are involved in protein folding and ER stress protection (Lindenmeyer et al., 2008; Rachidi et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2023; Tao et al., 2024), these data indicate that Alternol treatment potentially caused an unfolded protein response (UPR) and subsequent ER stress.

Figure 1. Alternol interacts with multiple chaperone proteins. (A–E) C4-2B cells were treated with Alternol (10 μM) for 2 h. Cell pellets were washed with cold PBS, and then lysed through two freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Cell lysates were aliquoted to 9 tubes and then heated at 37, 41, 45, 49, 53, 57, 61, 65, and 69°C for 3 min. After colling down on the ice for 2 min, the lysates were centrifuged for 20 min. The supernatants were collected for Western blot analysis. Average band density from three independent experiments was used for the curve fitting analysis as described previously in our publication (Li et al., 2019). (F,G) C4-2B cells were treated with Alternol in different concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10 μM) or periods (0, 2, 4, 8 h) at 10 μM. Cells were collected for Western blot analysis. β-Actin blot was used as the protein loading control.

Alternol induces ER stress responses via a ROS-dependent mechanismTo elucidate the detail of Alternol-induced UPR and ER stress response, we re-analyzed the RNA-seq data generated from Alternol-treated PC-3 cells as described in our recent publication (Li et al., 2021). As shown in Table 1, the most upregulated genes after Alternol treatment were inflammatory cytokines and ER stress responding factors, including CXCL8, IL1A, IL6, CXCL3, CCL20, CXCL2, DDIT3 (CHOP), IL1B, and ATF3. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that unfolded protein response (UPR) and PERK/ATF4-related ER stress response pathways were highly activated after Alternol treatment (Figure 2; Table 2). These data strongly suggest that Alternol treatment caused UPR and ER stress.

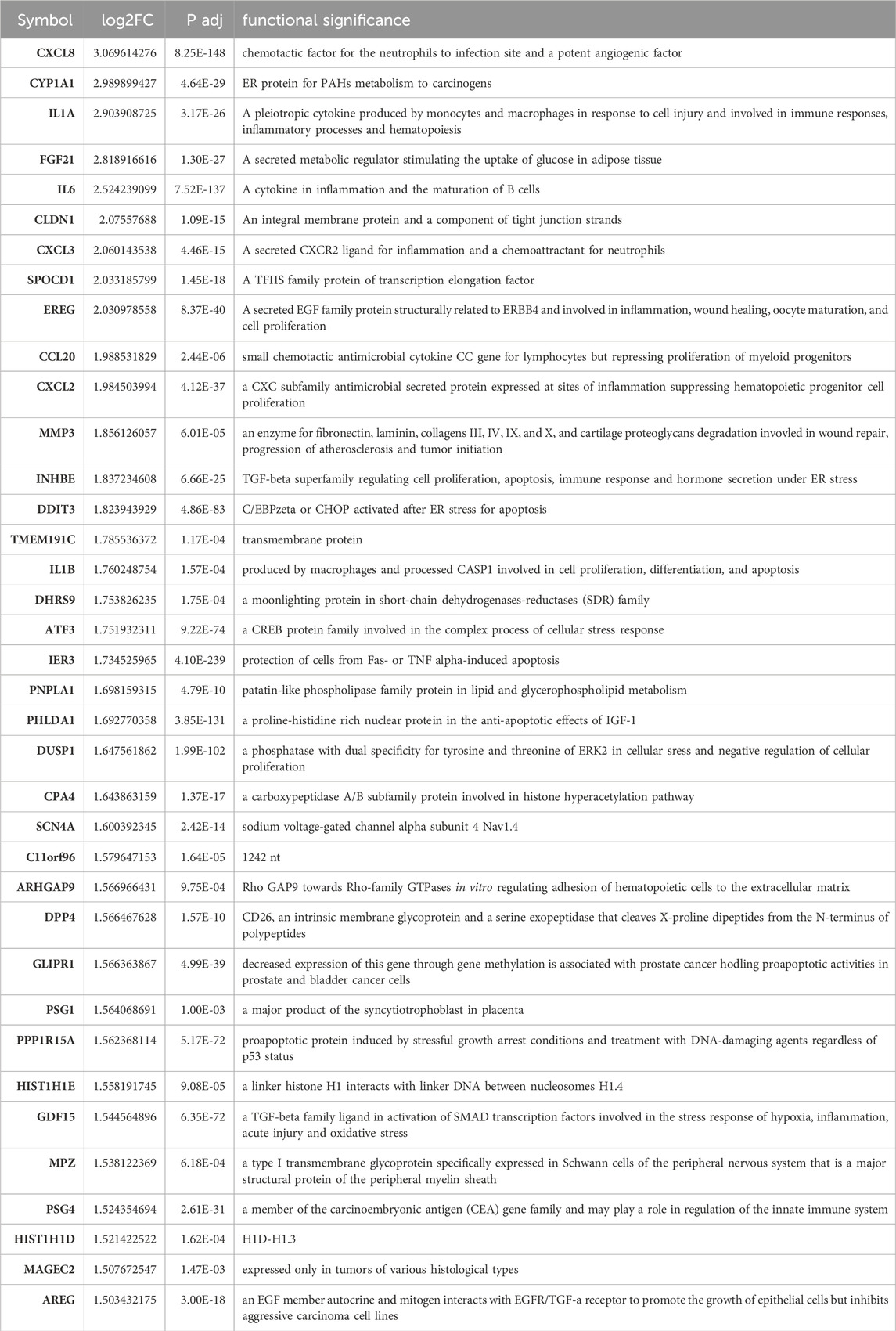

Table 1. The most significantly upregulated genes after Alternol treatment.

Figure 2. GSEA analysis of RNA-seq data for gene expression alterations after Alternol treatment. Activation of the unfolded protein response (A), ATF4 (B), and PERK (C) pathways was noticed in PC-3 cells after Alternol treatment.

Table 2. GSEA enrichment of ER stress and inflammatory pathways after Alternol treatment.

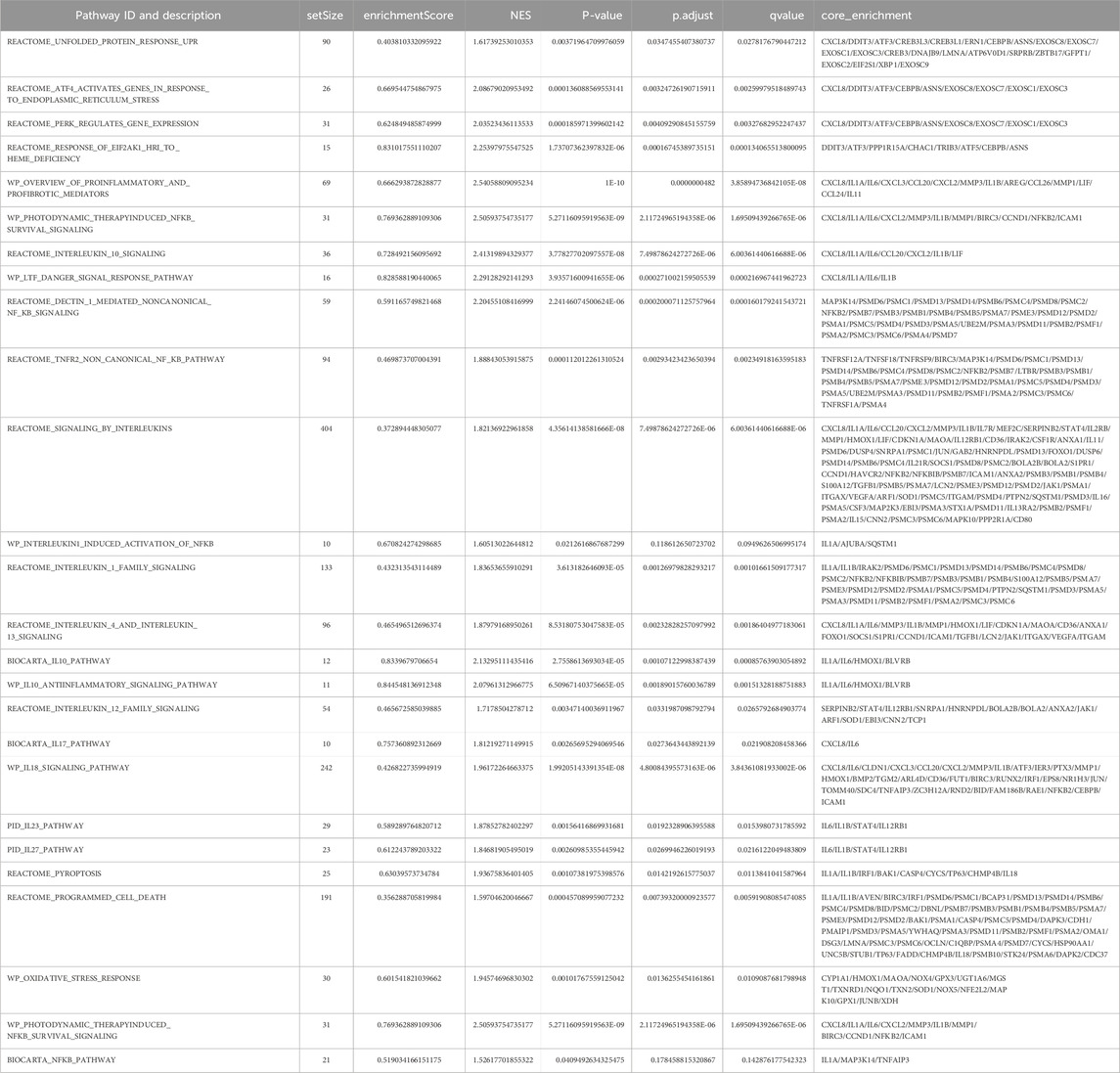

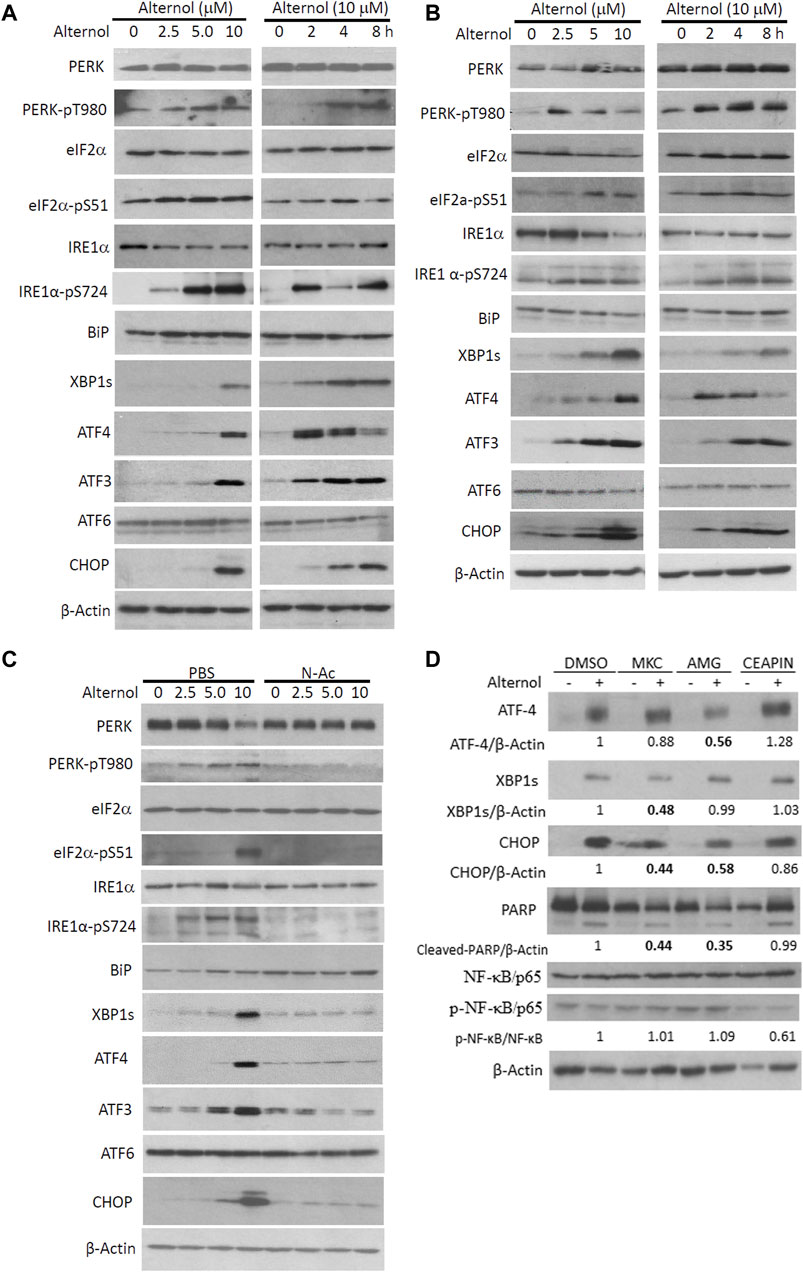

It is well known that UPR and ER stress responses are monitored by three major cascades modulated by PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6 (Hetz et al., 2020). Activation of these pathways induces modifications on downstream effector proteins, leading to translational alteration and ER stress responses (Wiseman et al., 2022). We analyzed Alternol-induced changes of these ER stress-responding proteins (Sicari et al., 2020). Our results from three different prostate cancer cell lines showed that PERK and IRE1α were phosphorylated at their activating domain (PERK/T980 and IRE1α/S724) as early as 2 h after Alternol treatment (Figures 3A–C). Meanwhile, PERK downstream effector eIF2α protein was phosphorylated at the S51 site (Harding et al., 1999) and IRE1α/ATF6 downstream effector XBP1s protein level was also largely increased. In addition, the expression levels of classical ER stress-responding ATF4/ATF3/CHOP proteins were drastically increased after Alternol treatment in dose-dependent and time-dependent fashions. Consistent with our previous reports (Tang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), ROS scavenger N-Ac pretreatment abolished these alterations related to ER stress responses (Figure 3C). These data demonstrated that Alternol treatment induced strong UPR and ER stress responses via ROS-dependent mechanism (Yoshida et al., 2001).

Figure 3. Alternol triggers ROS-dependent ER stress responses via PERK/IRE1α pathways. (A,B) PC-3 and 22RV1 cells were seeded in P100 dishes overnight and treated with Alternol at different concentrations or for the indicated period at 10 μM. (C) C4-2B cells were treated with Alternol at different concentrations as indicated with or without N-Ac (5 mM) for 6 h. (D) PC-3 cells were pre-treated with IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 (10 µM), PERK inhibitor AMG44 (1 µM), and ATF6 inhibitor CEAPIN-A7 (10 µM) for 30 min followed by Alternol (10 µM) for 4 h. Equal amounts of cellular proteins were subjected to western blots with the antibodies as indicated.

We then asked which one or a combination of the three ER stress-responding pathways (Ron and Walter, 2007) were involved in Alternol treatment-induced ER stress. We utilized pathway-selective pharmacological inhibitors for these three pathways, IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 (Sheng et al., 2019), PERK inhibitor AMG44 (Chintha et al., 2019), and ATF6 inhibitor CEAPIN-A7 (Xue et al., 2021) to determine their involvement in Alternol-induced ER stress response (Figure 3D). Our results showed that pretreatment with AMG44 reduced the Alternol-induced ATF4 expression while MKC8866 pretreatment suppressed Alternol-induced XBP1s expression. In addition, Alternol-induced CHOP protein expression was largely reduced by either AMG44 or MKC8866. Meantime, Alternol-induced PARP cleavage was also reduced by AMG44 or MKC8866. However, CEAPIN-A7 pre-treatment showed no significant attenuation on Alternol-induced these responses. These data suggest that both PERK and IRE1α cascades were involved in Alternol-induced UPR and ER stress.

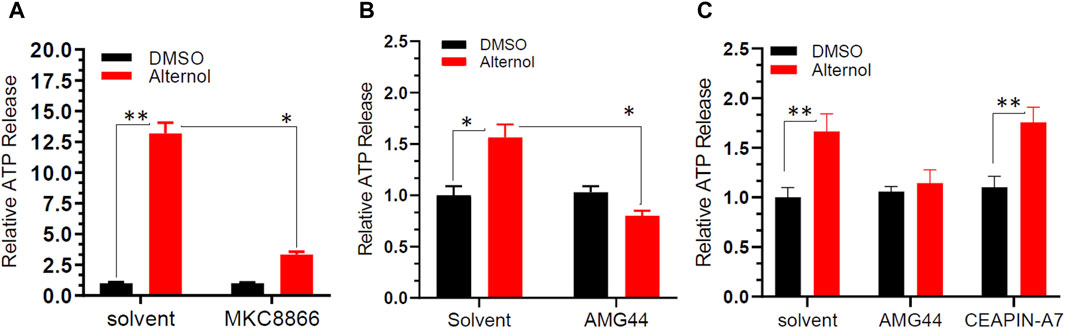

Alternol-induced ER stress is connected to immunogenic cell death-related ATP releaseExtracellular release of ATP molecules has been used as one of the hallmark indicators during immunogenic cell death under ER stress conditions (Galluzzi et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2024). Because we recently demonstrated Alternol-elicited ATP molecule release during immunogenic cell death (Li et al., 2021), we then determined if Alternol-induced ER stress responses were accompanied by immunogenic ATP release. C4-2B cells were pre-treated with IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866, followed by Alternol treatment. As shown in Figure 4A, the Alternol treatment induced a drastic elevation of extracellular ATP level, which was significantly suppressed by MKC8866 pre-treatment. Similarly, PERK inhibitor AMG44 but not ATF-6α inhibitor CEAPIN-A7 suppressed Alternol-induced ATP release in PC-3 cells (Figures 4B, C). These data suggest that Alternol-induced ER stress response was related to immunogenic cell death elicited by Alternol via PERK and IRE1α cascades.

Figure 4. Alternol induces ATP release through PERK and IRE1α-dependent pathways. C4-2B panel (A) or PC-3 panel (B,C) cells were seeded in a 96-well plate overnight, and then pre-treated with the solvent, MKC8866 (10 μM), AMG44 (1 μM), or CEAPIN-A7 (10 μM) for 30 min, followed by Alternol (10 μM) for 6 h. The ATP level in the cell culture media was measured using the ATPlite Luminescence Assay System (catalog number 6016941, PerkinElmer). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test.

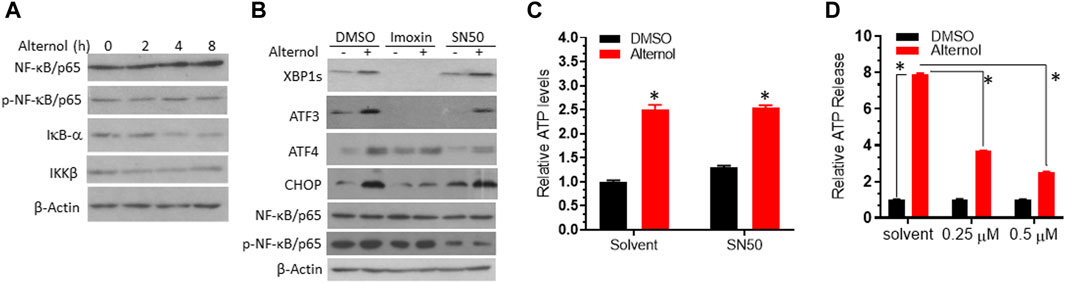

PKR but not the NF-κB pathway is involved in alternol-induced ER stress responsesNF-κB pathway is a crucial regulator of inflammatory cytokine production (Capece et al., 2022), and oxidative stress is a common factor of NF-κB activation (Kim et al., 2001). Oxidative stress-induced NF-κB activation has been implicated in immunogenic cell death (Zhao et al., 2022). We then asked if Alternol treatment activated the NF-κB pathway. We first re-analyzed the RNA-seq data with the GSEA approach. As expected, GSEA analysis revealed that the NF-κB pathway was enriched in Alternol-induced activation of gene expression (Table 2). We then evaluated the changes in major modulators of NF-κB activation including NF-κB/p65, IκBα, and IKKβ proteins. As shown in Figure 5A, Alternol treatment reduced the protein levels of IκB-α, the negative regulator of NF-κB activation, in a time-dependent manner. Next, we examined if NF-κB inhibition suppressed Alternol-induced ER stress responses and ATP release. Unexpectedly, pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor SN50 (Lin et al., 1995) had no significant suppression on Alternol-induced elevation of XBP1s and CHOP protein levels (Figure 5B), as well ATP release in PC-3 cells (Figure 5C), although SN50 slightly reduced ATF4 expression. As expected, SN50 largely reduced the phosphorylation level of NF-κB/p65, confirming the SN50 action (Wu et al., 2020). In addition, pretreatment with IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866, PERK inhibitor AMG44, and ATF6 inhibitor CEAPIN-A7 all had no significant effect on NF-kB phosphorylation (Figure 3D). These data indicate that NF-κB activation is not a major player in Alternol-induced ER stress responses and ATP release.

Figure 5. PKR but not the NF-κB pathway was involved in Alternol-induced ER stress. (A). PC-3 cells were treated with Alternol (10 μM) for 0, 2, 4, 8 h. (B) C4-2B cells were pre-treated with Imoxin (10 μM) or SN50 (10 μM) for 30 min followed by Alternol (10 μM) for 6 h. Equal amounts of cellular proteins were subjected to western blots with the antibodies as indicated. β-Actin blots served as the protein loading control. (C,D) PC-3 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate overnight and then pre-treated with the solvent, SN50 (panel C), or Imoxin (panel D) for 30 min, followed by Alternol treatment for 6 h. ATP level in the cell culture media was measured using the ATPlite™ Luminescence Assay System. *, p < 0.05, Student’s t-test.

Lastly, we evaluated the involvement of protein kinase R (PKR) in Alternol-induced ER stress response, since PKR was recently reported to modulate ER stress-related induction of ATF3, CHOP, and XBP1s expression (Guerra et al., 2006; Eo and Valentine, 2022). A PKR-specific inhibitor Imoxin (Nakamura et al., 2014) was utilized as a pretreatment during Alternol-induced ER stress. As shown in Figure 5B, Imoxin pretreatment largely reduced the protein levels of XBP1s and ATF3 at the basal and Alternol treatment conditions. Meanwhile, Imoxin also blunted the Alternol-induced increase of ATF4 and CHOP proteins. In addition, Imoxin significantly suppressed Alternol-induced ATP release in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5D). These data strongly suggest that PKR activation was involved in Alternol-induced ER stress response, leading to immunogenic cell death.

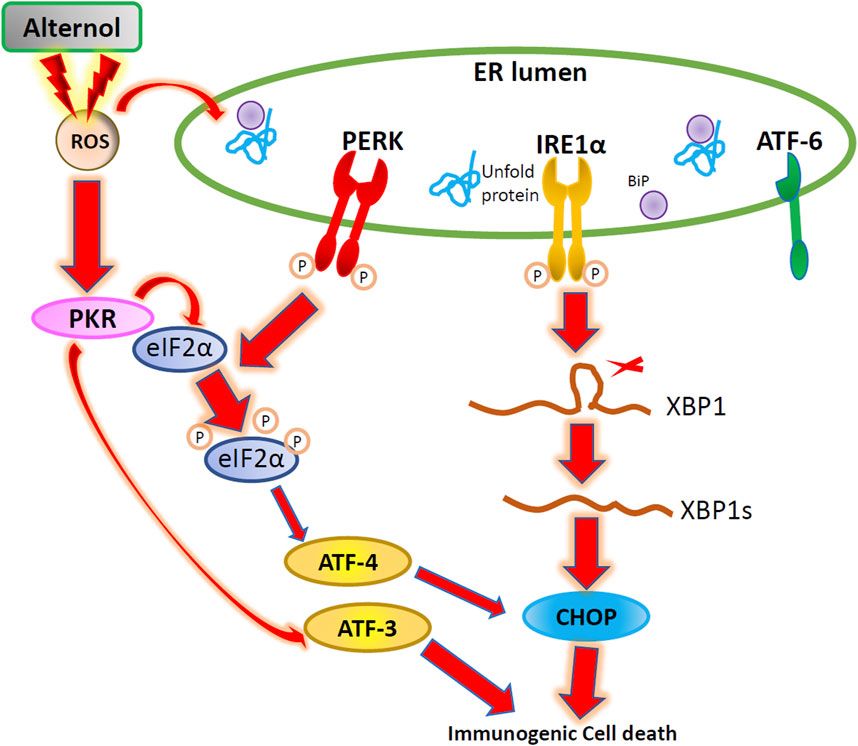

DiscussionIn this study, we demonstrated that Alternol interacted with multiple mitochondrial and ER chaperone proteins and elicited ROS-dependent ER stress responses in prostate cancer cells. Alternol-induced ER stress responses involved three protein kinases, PKR, PERK, and IRE1α, resulting in eIF2α phosphorylation, XBP1s processing, ATF3/ATF4 overexpression, and CHOP protein accumulation. Inhibition of these cascades suppressed immunogenic ATP release. According to the results, we proposed that Alternol induces immunogenic cell death via ER stress-related cascades of PKR, PERK, and IRE1α kinases.

Alternol is a novel small molecular compound and preclinical studies from our group and others have shown its potency in specifically killing multiple types of human cancer cells via ROS-dependent mechanism (Liu et al., 2020). Most interestingly, our recent studies discovered that Alternol-induced cancer cell killing elicited a strong immunogenic response that resulted in xenograft tumor suppression in immune-intact mice (Li et al., 2021). Consistent with the notion that ER stress response is crucial in DAMP release and immunogenic elicitation (Aria and Rezaei, 2023), in this study, our data confirmed the ER stress responses after Alternol treatment in prostate cancer cells. Our studies discovered that three ER stress-related protein kinases, PKR, PERK, and IRE1a, were involved in Alternol-induced ER stress responses and immunogenic ATP release. Our results also verified our previous report (Li et al., 2019) that Alternol interacted with five chaperone proteins resided in mitochondria and ER and Alternol treatment increased their expression levels, a potential response due to the UPR and ER stress.

It is well known that there are three sensor kinases, IRE1α, PERK, and ATF-6, responding to ER stress conditions (Hetz et al., 2020; Sicari et al., 2020). IRE1α induces the unconventional splicing of XBP1 mRNA to produce a shorter XBP1s protein, PERK kinase induces eIF2α phosphorylation at serine 51 to inactivate protein translation, and ATF6 N-terminal region exerts a transcriptional activity to upregulate UPR-related gene after undergoing proteolytic cleavage (Hetz et al., 2020; Saaoud et al., 2024). In this study, our data revealed that PERK and IRE1α but not ATF6 cascades were involved in Alternol-induced ER stress. ATF6 protein did not show a proteolytic change and its specific inhibitor failed to suppress XBP1 expression and immunogenic ATP release after Alternol treatment. A further mechanistic study is warranted to dissect Alternol-induced activation of PERK and IRE1α cascades, although ROS dependency was confirmed (Li et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024).

PKR is one of the four eIF2α kinases (Jackson et al., 2010) and it is mainly activated after viral infection in mammalian cells (Park et al., 2006; Zhang and Karijolich, 2024). However, recent studies showed that PKR activation was also involved in eIF2α/S51 phosphorylation and immunogenic cell death induced by chemo-drugs in melanoma and breast cancer cells (Giglio et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022). In addition, PKR-specific inhibitor Imoxin suppressed saturated fatty acid-induced ER stress responses including XBP1s processing, ATF6, and CHOP expression (Eo and Valentine, 2022). Interestingly, we also found that Imoxin pretreatment almost blunted Alternol-induced XBP1s, largely reduced ATF4 and CHOP expression, and significantly reduced immunogenic ATP release, indicating a signaling crosstalk among the conventional ER stress sensors and PKR during Alternol-induced ROS-dependent immunogenic response.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that Alternol treatment triggered ROS-dependent ER stress responses, linking to immunogenic ATP release. We also proved that Alternol-induced ER stress involved three protein kinases, IRE1α, PERK, and PKR, but not ATF6 protein (Figure 6). Further mechanistic investigation is needed to dissect the crosstalk among these three kinase cascades under oxidative stress.

Figure 6. The Schematic drawing for Alternol-induced ER stress in prostate cancer. Alternol treatment causes ROS accumulation, leading to PKR, PERK, and IRE1α activation and subsequent eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF3/ATF4 transactivation, XBP1 splicing, and CHOP expression.

Data availability statementThe datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/705723.

Author contributionsWL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Data curation, Formal Analysis. CH: Data curation, Methodology, Writing–original draft. CL: Data curation, Writing–original draft. SY: Data curation, Writing–original draft. JZ: Data curation, Writing–original draft, Methodology. CZ: Data curation, Writing–original draft. XW: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Writing–review and editing. QM: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Writing–review and editing. BL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was partially supported by grants from the national key R&D program (2020YFA0908800) and the 2024 special funding from Guangdong Medical University (4SG24016G) to XW and by Ningbo Clinical Research Center Fund (#2019A21001) to QM.

AcknowledgmentsWe are very grateful for the generous gift of Alternol reagent from Dr Jiepeng Chen at Sungen Biosciences (Shantou, China).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ReferencesAria, H., and Rezaei, M. (2023). Immunogenic cell death inducer peptides: a new approach for cancer therapy, current status and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114503. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114503

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Capece, D., Verzella, D., Flati, I., Arboretto, P., Cornice, J., and Franzoso, G. (2022). NF-κB: blending metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 43 (9), 757–775. doi:10.1016/j.it.2022.07.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Celik, C., Lee, S. Y. T., Yap, W. S., and Thibault, G. (2023). Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipids in health and diseases. Prog. Lipid Res. 89, 101198. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2022.101198

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chintha, C., Carlesso, A., Gorman, A. M., Samali, A., and Eriksson, L. A. (2019). Molecular modeling provides a structural basis for PERK inhibitor selectivity towards RIPK1. RSC Adv. 10 (1), 367–375. doi:10.1039/c9ra08047c

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

de la Calle, C. M., Shee, K., Yang, H., Lonergan, P. E., and Nguyen, H. G. (2022). The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19 (12), 708–726. doi:10.1038/s41585-022-00649-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Eo, H., and Valentine, R. J. (2022). Saturated fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance are prevented by Imoxin in C2C12 myotubes. Front. Physiol. 13, 842819. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.842819

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ernst, R., Renne, M. F., Jain, A., and von der Malsburg, A. (2024). Endoplasmic reticulum membrane homeostasis and the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 22, a041400. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a041400

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Galluzzi, L., Vitale, I., Warren, S., Adjemian, S., Agostinis, P., Martinez, A. B., et al. (2020). Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J. Immunother. Cancer 8 (1), e000337. doi:10.1136/jitc-2019-000337

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Giglio, P., Gagliardi, M., Tumino, N., Antunes, F., Smaili, S., Cotella, D., et al. (2018). PKR and GCN2 stress kinases promote an ER stress-independent eIF2α phosphorylation responsible for calreticulin exposure in melanoma cells. Oncoimmunology 7 (8), e1466765. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2018.1466765

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guerra, S., Lopez-Fernandez, L. A., Garcia, M. A., Zaballos, A., and Esteban, M. (2006). Human gene profiling in response to the active protein kinase, interferon-induced serine/threonine protein kinase (PKR), in infected cells. Involvement of the transcription factor ATF-3 IN PKR-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (27), 18734–18745. doi:10.1074/jbc.M511983200

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Harding, H. P., Zhang, Y., and Ron, D. (1999). Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397 (6716), 271–274. doi:10.1038/16729

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

He, C., Duan, S., Dong, L., Wang, Y., Hu, Q., Liu, C., et al. (2017). Characterization of a novel p110β-specific inhibitor BL140 that overcomes MDV3100-resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Prostate 77 (11), 1187–1198. doi:10.1002/pros.23377

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hetz, C., Zhang, K., and Kaufman, R. J. (2020). Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21 (8), 421–438. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jackson, R. J., Hellen, C. U., and Pestova, T. V. (2010). The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 (2), 113–127. doi:10.1038/nrm2838

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, D. K., Cho, E. S., Lee, B. R., and Um, H. D. (2001). NF-kappa B mediates the adaptation of human U937 cells to hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30 (5), 563–571. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00504-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, C., He, C., Xu, Y., Xu, H., Tang, Y., Chavan, H., et al. (2019). Alternol eliminates excessive ATP production by disturbing Krebs cycle in prostate cancer. Prostate 79 (6), 628–639. doi:10.1002/pros.23767

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, C., Sun, H., Wei, W., Liu, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., et al. (2020). Mitoxantrone triggers immunogenic prostate cancer cell death via p53-dependent PERK expression. Cell Oncol. (Dordr) 43 (6), 1099–1116. doi:10.1007/s13402-020-00544-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, C., Wang, X., Chen, T., Li, W., Zhou, X., Wang, L., et al. (2022). Huaier induces immunogenic cell death via CircCLASP1/PKR/eIF2α signaling pathway in triple negative breast cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 913824. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.913824

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, C., Zhang, Y., Yan, S., Zhang, G., Wei, W., Qi, Z., et al. (2021). Alternol triggers immunogenic cell death via reactive oxygen species generation. Oncoimmunology 10 (1), 1952539. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2021.1952539

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, X., Liu, Y. H., Zhang, H. Q., Wu, L. W., Li, Q., Deng, J., et al. (2023). DSCC1 interacts with HSP90AB1 and promotes the progression of lung adenocarcinoma via regulating ER stress. Cancer Cell Int. 23 (1), 208. doi:10.1186/s12935-023-03047-w

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, Y. Z., Yao, S. Y., Veach, R. A., Torgerson, T. R., and Hawiger, J. (1995). Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (24), 14255–14258. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lindenmeyer, M. T., Rastaldi, M. P., Ikehata, M., Neusser, M. A., Kretzler, M., Cohen, C. D., et al. (2008). Proteinuria and hyperglycemia induce endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19 (11), 2225–2236. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007121313

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, P., Zhao, L., Zitvogel, L., Kepp, O., and Kroemer, G. (2024). Immunogenic cell death (ICD) enhancers-Drugs that enhance the perception of ICD by dendritic cells. Immunol. Rev. 321 (1), 7–19. doi:10.1111/imr.13269

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, W., Li, J. C., Huang, J., Chen, J., Holzbeierlein, J., and Li, B. (2020). Alternol/alteronol: potent anti-cancer compounds with multiple mechanistic actions. Front. Oncol. 10, 568110. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.568110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martinez Molina, D., Jafari, R., Ignatushchenko, M., Seki, T., Larsson, E. A., Dan, C., et al. (2013). Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science 341 (6141), 84–87. doi:10.1126/science.1233606

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nakamura, T., Arduini, A., Baccaro, B., Furuhashi, M., and Hotamisligil, G. S. (2014). Small-molecule inhibitors of PKR improve glucose homeostasis in obese diabetic mice. Diabetes 63 (2), 526–534. doi:10.2337/db13-1019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Park, S. H., Choi, J., Kang, J. I., Choi, S. Y., Hwang, S. B., Kim, J. P., et al. (2006). Attenuated expression of interferon-induced protein kinase PKR in a simian cell devoid of type I interferons. Mol. Cells 21 (1), 21–28. doi:10.1016/s1016-8478(23)12898-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rachidi, S., Sun, S., Wu, B. X., Jones, E., Drake, R. R., Ogretmen, B., et al. (2015). Endoplasmic reticulum heat shock protein gp96 maintains liver homeostasis and promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 62 (4), 879–888. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rufo, N., Garg, A. D., and Agostinis, P. (2017). The unfolded protein response in immunogenic cell death and cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 3 (9), 643–658. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2017.07.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Saaoud, F., Lu, Y., Xu, K., Shao, Y., Pratico, D., Vazquez-Padron, R. I., et al. (2024). Protein-rich foods, sea foods, and gut microbiota amplify immune responses in chronic diseases and cancers - targeting PERK as a novel therapeutic strategy for chronic inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 255, 108604. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2024.108604

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sheng, X., Nenseth, H. Z., Qu, S., Kuzu, O. F., Frahnow, T., Simon, L., et al. (2019). IRE1α-XBP1s pathway promotes prostate cancer by activating c-MYC signaling. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 323. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08152-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sicari, D., Delaunay-Moisan, A., Combettes, L., Chevet, E., and Igbaria, A. (2020). A guide to assessing endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and stress in mammalian s

留言 (0)