Earth, formed 4.6 billion years ago, is divided into seven continents: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia (1). Asia is the largest and most populous continent (2). Asia’s vast geographical area offers a population advantage, comprising 4.6 billion out of the global population of 7.7 billion (3). The Asian region comprises a diverse array of countries, including some of the world’s least and most developed nations (4). The East Asia and Pacific region, with over two billion people, is the most populous globally, home to fast-growing economies and the second-largest number of fragile states after Africa (5).

Healthcare systems in Asia are diverse (6–8), with Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan renowned for advanced systems, high care standards, and UHC (9–11). Governments in some Asian countries ensure healthcare access through public funding and provider regulation (12), while other Asian countries face challenges like limited access, inadequate infrastructure, and disparities in healthcare delivery (9). As a result, Asian countries are prioritizing healthcare infrastructure investment, quality access, and addressing non-communicable diseases (13, 14), while promoting collaboration and knowledge-sharing to improve health outcomes (15). Hence, Asia’s healthcare systems are undergoing significant transformations and reforms to improve access, quality, and affordability of services for their unique challenges (16, 17).

Africa is the world’s second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia. It spans approximately 30.3 million km2, including adjacent islands, accounting for 6.0% of Earth’s surface area and 20.0% of its land area. With a 2021 population of 1.4 billion, it comprises about 18.0% of the global human population (18). The majority of the African population, comprising 53.3%, is rural, with a median age of 18.8 years (19), the youngest population worldwide (18).

Healthcare systems in Africa encounter multiple challenges, such as institutional, human resources, financial, technical, and political issues (20). Africa is grappling with a significant number of both communicable and non-communicable diseases (21). The African continent was home to a particularly diverse and deadly set of tropical diseases (20). Cost-effective interventions to prevent disease burden are available, but their coverage is limited by weaknesses in health systems (21).

Background and rationaleThe primary objective of an efficient health system is to improve public health (22, 23), which critically requires UHC (22). The concept of UHC was introduced in 2005 with the aim of addressing disparities in access to healthcare services (24). The post-2015 sustainable development agenda proposes UHC as an umbrella health goal, aiming for universal, equitable, and effective delivery of comprehensive health services (25), which is at the heart of contemporary efforts to strengthen health systems (26).

However, financing UHC is a challenging task, requiring countries to consider all revenue sources for healthcare system reform (27). On the other hand, while increased spending can improve health outcomes, improving the efficiency of these expenditures is even more critical (28). Health financing involves the collection of revenue, pooling of risk, and purchasing of goods and services to enhance population health, primarily funded by individuals and households through the tax system (29). Not only revenue collection but also effective healthcare purchasing and proper regulation of healthcare providers are crucial for the sustainability of healthcare financing (30). Health purchasing is the transfer of funds to health providers, either passively or strategically, to deliver services (31).

As mentioned before, one of the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is the promise to work toward achieving UHC by 2030 (32). UHC not only contributes to achieving SDG 3, good health and wellbeing, but also poverty eradication, work and economic growth, and reduced inequalities, which represent the targets of SDGs 1, 8, and 10, respectively (33). It should shield households from financial risk, especially the poorest who find it difficult to pay for services (34), which include access to high-quality, vital medical care as well as safe, effective, and reasonably priced medicines and vaccinations (32). The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the significance of equitable access to safe and affordable medicines for optimal health, aligning with the SDGs, particularly SDG 3.8, which aims for UHC, and SDG 3.b, which focuses on the accessibility of medicines to address existing treatment gaps (35).

Yet, 2 billion people worldwide have no access to essential medicines (35) and face catastrophic or impoverished health spending (36), and at least 400 million individuals do not have access to essential health services (32), because the most common method of paying for health services globally is OOP spending (37). On average, each nation spends roughly 32.0% of its total health budget on OOP expenses. Due to OOP medical expenses, 150 million individuals each year experience financial catastrophe (32), and 100 million are forced into poverty (32, 38). These individuals reside in developing countries where the health systems are plagued by inefficiency, unequal access, insufficient funding, and substandard services and account for 92.0, 68.0, and 80.0% of the world’s annual deaths from communicable diseases, non-communicable conditions, and injuries, respectively (39).

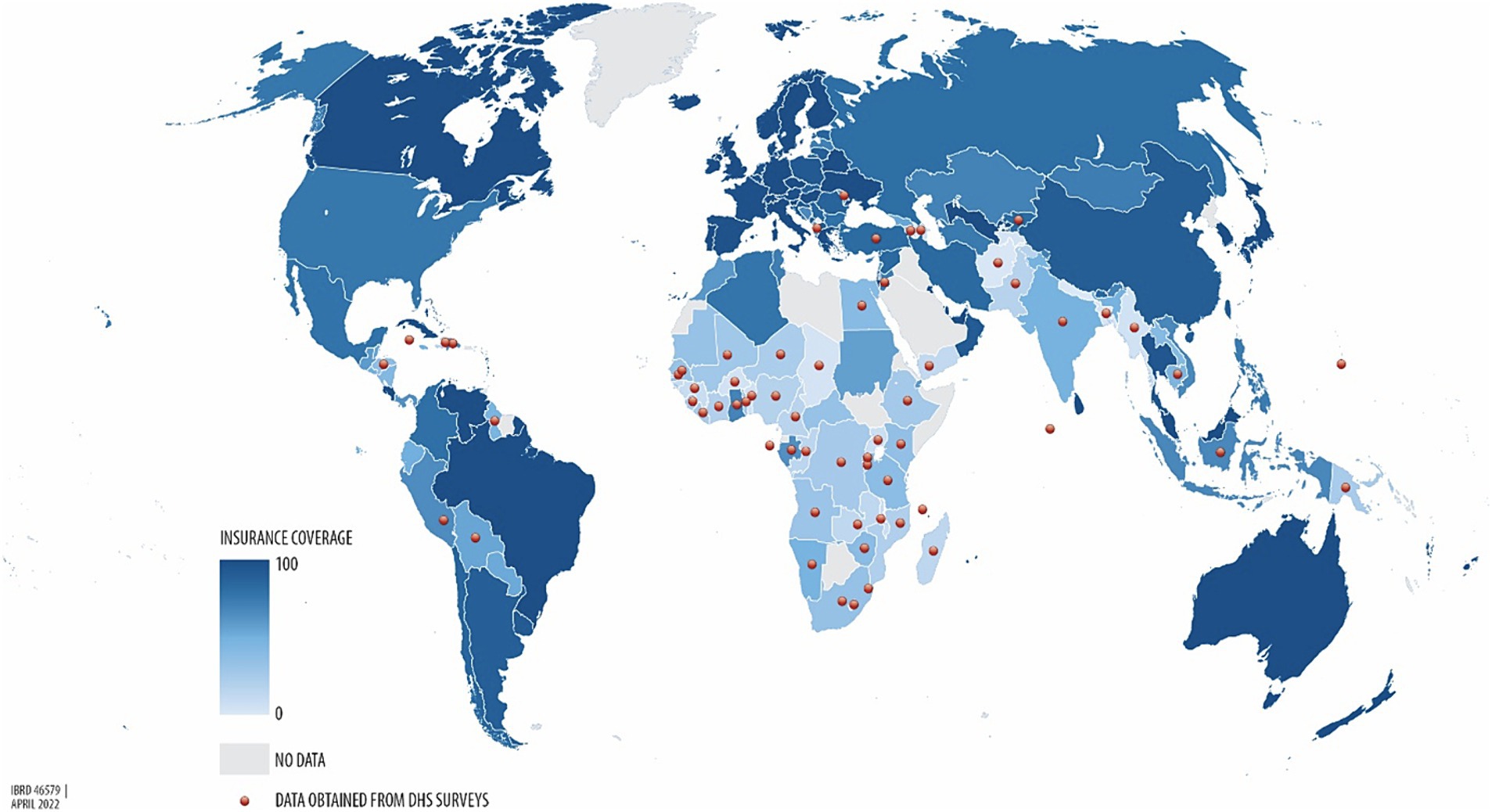

The burden of the lack of UHC is highest in LMICs, particularly in Africa and Asia (Figure 1) (40), where 97.0% of the population is impoverished by OOP health spending (33). In 2023, 75.0% of the 3.1 billion people worldwide without effective UHC are from LMICs in South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (41). For example, by using their household income to access healthcare services, medications, and other products, an estimated 11 million Africans fall into poverty each year (33), which is a concerning issue considering that Asia and Africa together constitute over 75% of the global population (41).

Figure 1. Percentage of health insurance coverage across the world, from the lowest UHC (light blue) to the highest UHC (dark blue) (40).

Nevertheless, a system that generates net savings by eliminating profit and waste can be used to address the rapidly rising health expenditures (42), because up to one fifth of health expenditures could be directed towards better use by avoiding waste (43). To ensure equitable access through such a mechanism, health care must be funded, managed, and provided in a way that puts the needs of individuals and communities first (32), which is embedded in national, regional, and international contexts (44). This implies that improving health system performance to attain UHC requires actions at national, regional, and global levels (45). In fact, the dedication to collaborating with the global health community enhances access to quality healthcare and makes UHC a reality for patients, families, and communities worldwide. Together, this effort will lead to healthier communities and stronger economies (46).

Accordingly, to overcome the challenge to achieve UHC, the two regions, Africa and Asia, have recognized the importance of collaboration among governments, civil society, and the private sector. Consequently, they have started working together to use a global south perspective. Kenya and Egypt, for instance, are looking for guidance on free basic healthcare through health insurance from Thailand and Japan, respectively (33), which is, undoubtedly, the most significant sort of insurance (47).

Insurance is a contract where the subscriber pays the insurer on a regular basis in exchange for the assurance of indemnification against specific risks. The specific risks covered by health insurance are the financial burden of the treatments required following an illness or injury (48). There are several reasons to introduce health insurance, including the removal of financial barriers to healthcare access, providing financial protection against high medical costs, and negotiating better-quality healthcare with providers (49), which dictate that the way of funding health services is a crucial aspect of UHC (50). As a result, health policymakers must prioritize selecting the appropriate financing mechanisms for health services to achieve broader health policy goals, as this decision impacts both providers and consumers, particularly in low-income countries (LICs) where service usage rates across income groups are a significant issue (51).

Though there are various healthcare financing mechanisms to choose from, national, social, private, and community-based health insurance programs are the four main categories of health insurance programs (52, 53), dictating that health insurance programs can be privately or publicly run, cover various population subgroups, and provide different premium costs and benefit packages. The two primary types of government health insurance programs are NHI and Social Health Insurance (SHI), which are based on the Beveridge and Bismarck healthcare systems, respectively. Health insurance programs in many nations include components from both of these models, and the design varies across countries. However, in the majority of government health insurance schemes, enrollment, contributions, and payments are managed by a fully or partially independent government body (52).

Public health insurance models provide benefits through either a national health insurance fund, a national social security fund, or branches of the central government (54). NHI, as a public health insurance scheme, is thus provided by the federal government through general taxation (55), usually with mandatory coverage for all citizens (56). It is a single-payer scheme that covers all citizens and residents, with eligibility based on citizenship and residency status (57), indicating that it is the best option to ensure equity, fairness, and priorities aligned with medical needs. This strategy improves public health by providing universal access to desirable care with treatment options tailored to the patient’s needs (42).

Therefore, as health care is a human right and requires system-wide changes in financing to achieve UHC (58), a public, single-payer system is the best, most efficient, and most equitable health-care system. This is because, through partnerships with provider organizations and the use of taxes for everyone, single-payer systems enable people to serve as their own insurers. The best care to satisfy needs is then selected by the consumer, with minimal or no OOP expenses. That is, patients are partners in their care, obtaining diagnosis, treatment, and prevention services without financial restrictions (42). Hence, it is important to bear in mind that a nation’s financial resources primarily originate from its population, with the exception of external aid and natural resources (56).

Thus, NHI is funded through income-based premiums (59). The premium is the cost of insurance coverage, which is typically paid monthly or yearly (52). This cost of a health insurance plan is a key factor in its viability, which is determined by the members’ WTP (60), i.e., a stated preference that involves assigning a monetary value to the benefits of health-related goods or services (61). However, LICs face constraints in raising revenue to finance health and health insurance, as government tax revenues are only 15% of gross domestic product (GDP), compared to over 20% in higher-income countries (HICs) (56), and the tax structure is often regressive (62).

The WTP is the utmost amount of money that an individual is WTP for a service or product (52). It is a proxy measure of cost–benefit trade-offs in health insurance (63) and is one of two popular approaches for estimating the monetary value of health benefits, the other being the Human Capital (HC) approach (64). WTP is a widely-used concept in the health sector to guide policy decisions (65). The assessment of WTP can be conducted through evaluating historical healthcare utilization and expenditure data or by employing a contingent valuation (CV) approach (66), which is a survey methodology to assess the benefit or worth of a program to individuals (67). When employing the CV method to determine WTP, two general elements should be included: a hypothetical scenario and a bidding vehicle. The goal of the hypothetical scenario is to give the respondents a detailed explanation of the good or service they are being asked to pay for. Bids can be obtained in a number of ways, including open-ended or closed-ended questions, a bidding game, or a payment card (64).

Estimating the WTP is the best way to assess the expected income of health insurance schemes. This estimate is required to ensure that the cost of benefit packages does not surpass available resources to minimize the risk of bankruptcy. WTP data are, therefore, crucial for informing the design of tailored benefit packages for consumers, particularly groups or communities (68). Cross-country studies are decisive in assessing such data and the impacts of common elements of reforms adopted by many countries, as they provide a comprehensive understanding of which reforms have been successful or not (22). Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the pooled WTP for NHI and its influencing factors from the available literature in Africa and Asia.

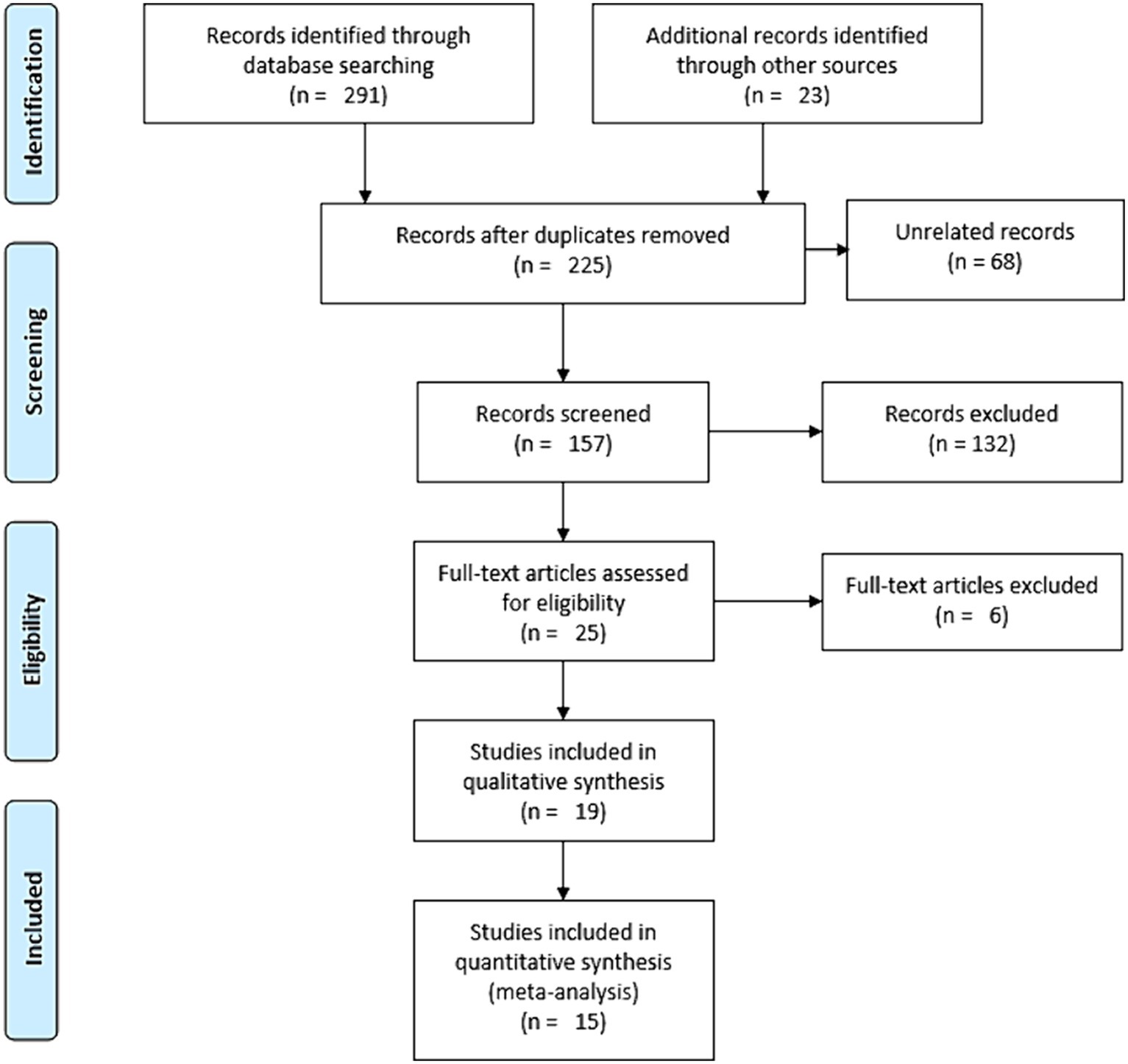

Methods Registration and protocolThe protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO, accessible at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023411411. We used the PRISMA 2020 Statement as a frame for the review (69) (Supplementary file S1). However, to pictorially present the screening process of the studies, because of its ease and clarity, we used the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (70), while we sufficiently discussed the screening process in words in line with the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Eligibility criteriaAll original and published cross-sectional studies that report the prevalence of WTP for NHI and/or factors influencing it were deemed eligible for the systematic review. We considered all English-language studies conducted in both community and institutional settings on WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia. The selection of studies was also based on several parameters including outcome variables, study population, year of the study, regional context, sample size, and response rate.

Information sources and search strategyDatabase searches were conducted on Scopus, HINARI, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Semantic Scholar from March 31 to April 4, 2023 (Supplementary file S2). Manual searches were performed on PubMed and HINARI. Conversely, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Semantic Scholar were searched using the “Publish or Perish” database searching tool, version 8 (71).

Selection processAfter excluding duplicate studies using Zotero reference manager version 6, two reviewers, EMB and HNT, independently screened the remaining studies. The selection process was meticulously conducted by these researchers. Initially, articles were refined based on their title and abstract; subsequently, a full-text revision was performed independently and then collaboratively until a consensus was reached. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted for resolution.

Data collection process and data itemsA Microsoft Excel 2019 spreadsheet was utilized for data extraction. The outcome variables - population (study units), year of study, context, sample size, response rate, and proportions - were extracted using this spreadsheet. Two independent reviewers, EMB and HNT, extracted the data, compared their findings and reached a consensus. In cases where agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer was invited to help achieve consensus. Additionally, we reached out to the authors of the study to gather any missing information. The primary outcome of this systematic review and meta-analysis was the WTP for NHI. An additional outcome was the factors influencing the WTP for NHI.

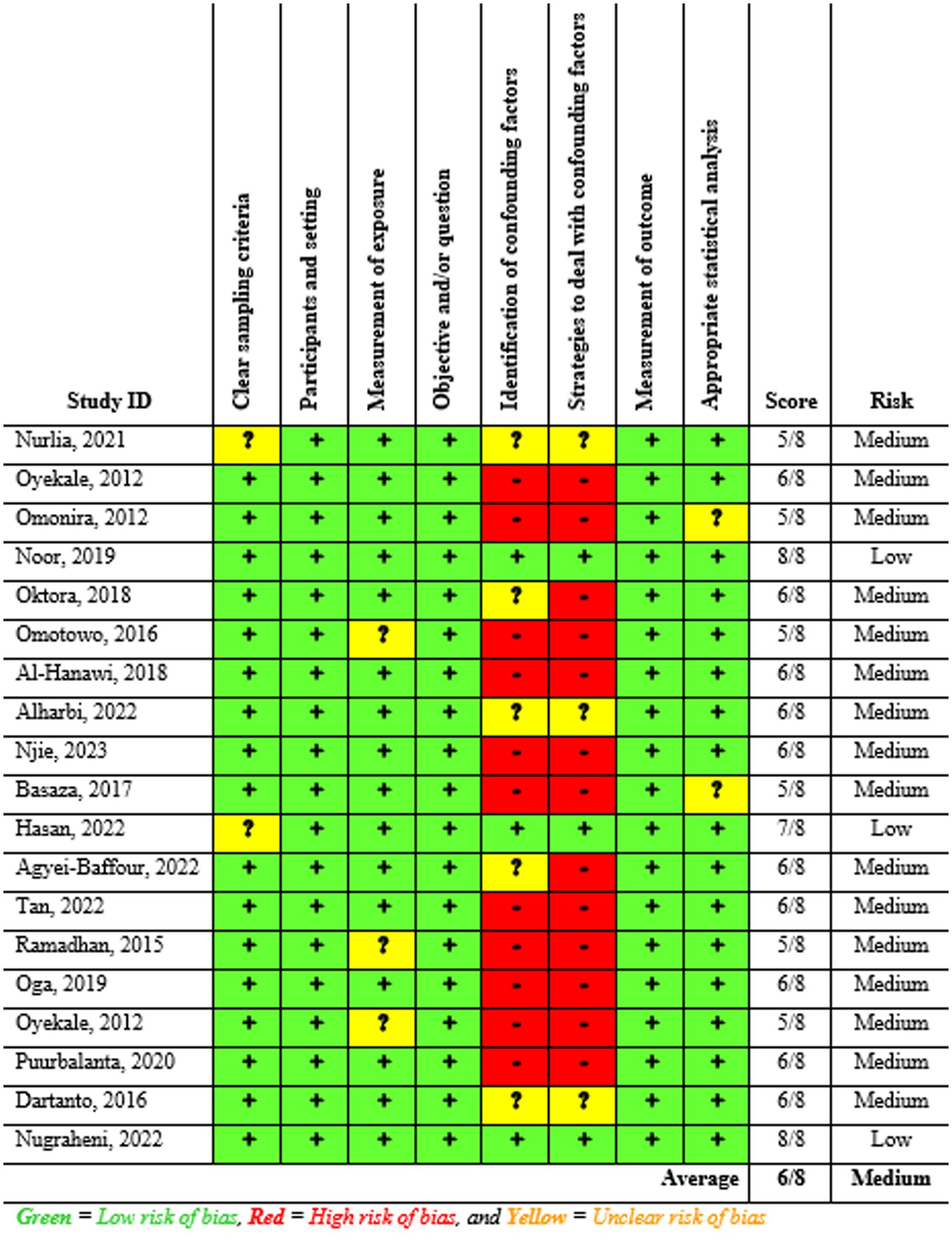

Study risk of bias assessmentTwo reviewers, EMB and HNT, independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using JBI tools. The assessment focused on several criteria: inclusion in the sample, descriptions of study subjects and settings, validity and reliability of measurements, confounding factors and strategies to address them, and appropriateness of the outcome measure. The JBI’s tool with eight criteria was used to evaluate the risk of bias within the articles. Scores of 7 or higher were classified as low risk, 5–6 as medium risk, and 4 or lower as high risk. Studies identified as low and medium risk were included in the review. All inconsistencies were addressed through discussion and, if necessary, the involvement of a third reviewer.

Effect measures and synthesis methodsFor the qualitative synthesis, thematic strategies were utilized to categorically conceptualize the outcome variables. Preliminary effect measures were then calculated for the quantitative synthesis based on the qualitative synthesis using a Microsoft Excel 2019 spreadsheet. STATA 17 was employed to determine the effect estimates (proportions and odds ratios—ORs) of the WTP for NHI. Sub-group analyses were subsequently conducted to compare these effect estimates across studies focusing on the outcome variable. The overall level of statistical significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Reporting bias and certainty assessmentThe study authors were contacted to obtain missing or incomplete data. Studies with incomplete data were excluded from the analysis. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. The influence of each study on the overall meta-analysis was measured using percentages of weights, and subgroup analysis comparing the WTP for NHI in Asia and Africa was conducted. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to determine the outlier studies.

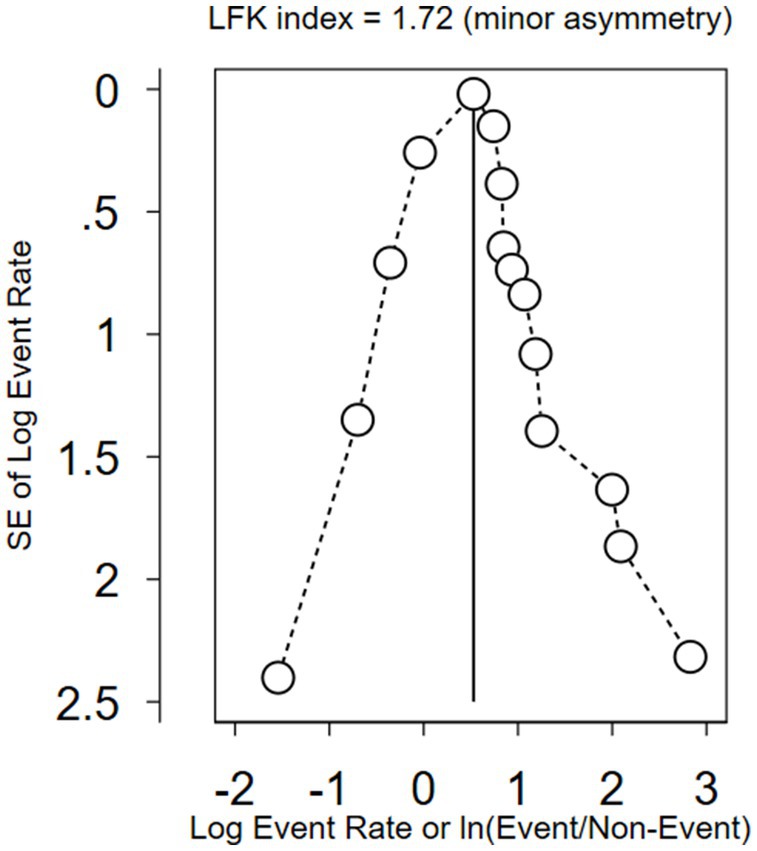

Moreover, Doi plots were used to examine potential inter-study bias, also known as publication bias, which helps to calculate asymmetry using the LFK index (72). The Doi plot, which is a folded normal quantile (z-score) versus effect plot, replaces the conventional scatter (funnel) plot of precision versus effect. It provides a quick overview of study symmetry and heterogeneity when combined with the Galbraith plot (73). The visual examination involves observing the dots representing specific studies and their arrangement (74). In addition, the plots comprise the LFK index and p-value of Egger’s test (73). The LFK index is used to identify and measure the asymmetry of study effects (75). The closer the LFK index value is to zero, the greater the symmetry in the Doi plot. Values of the LFK index that fall outside the range of −1 to +1 suggest asymmetry, indicative of publication bias (76).

Results Study selectionWe conducted a comprehensive search of Google Scholar (n = 200), HINARI (n = 50), Scopus (n = 19), and PubMed (n = 22) from March 31 to April 4, 2023. An additional 23 records were identified through other sources, resulting in a total of 314 resources (Figure 2). After eliminating duplicates, we were left with 225 articles. Out of these, we screened 157 papers for relevance and discarded 68. Subsequently, 25 studies were chosen based on title and abstract evaluation. After a full-text evaluation, six studies were excluded due to reasons such as language other than English (77), high risk of bias (78–81), and inaccessibility of the full text (82). In conclusion, 19 resources were identified for inclusion, out of which 15 were deemed suitable for the quantitative meta-analysis.

Figure 2. Schematic description of the screening processes for literature, 2023.

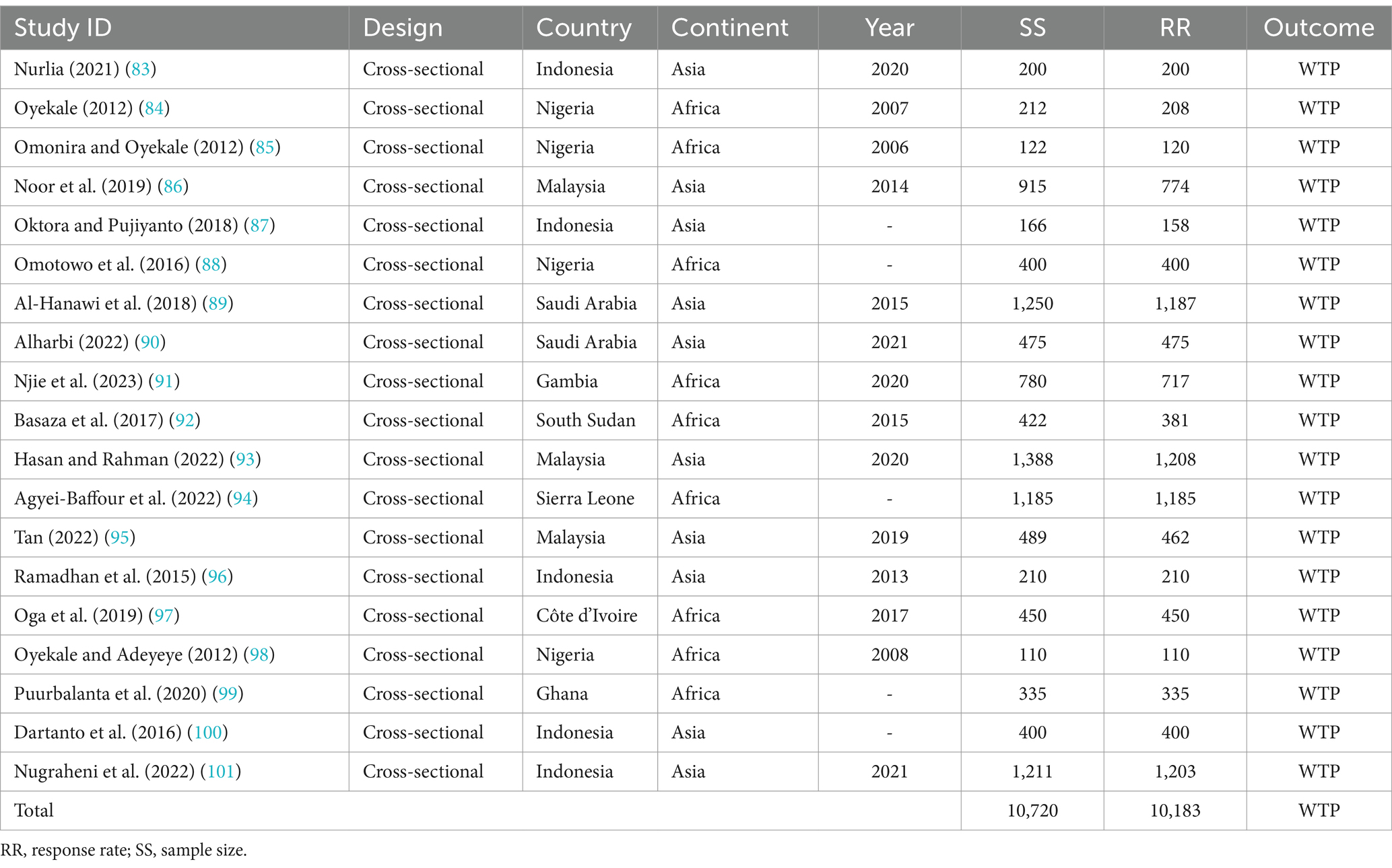

Study characteristicsTen of the studies included in the systematic review were conducted in Asia, and nine were conducted in Africa. The Asian studies took place in Indonesia (n = 5), Malaysia (n = 3), and Saudi Arabia (n = 2). The African studies were carried out in Nigeria (n = 4), Gambia, South Sudan, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana. Each study was evaluated based on its design, context, year of study, sample size, non-response and response rates, and primary outcome. The individual characteristics of each study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies (n = 19), 2023.

Risk of bias in the included studiesThe risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using JBI’s critical appraisal tool. Subsequently, studies with low and medium risk were incorporated into the review. As depicted in (Figure 3), the average risk of bias across the studies was 6.0 (75%).

Figure 3. Summary of the risk of bias assessment of the included studies (n = 19), 2023.

Results of synthesis Qualitative synthesisAs shown in Table 1, the sample population for all included studies (n = 19) comprised 10,720 individuals, with a response rate of 95.0%, equating to 10,183 respondents. The WTP for NHI was found to be significantly affected by various factors, which were categorized into seven themes as follows:

1. Socio-demographic factors: family size (83–85, 89, 92, 93, 100, 101), age (84, 86, 87, 90, 94, 95, 99), marital status (85, 86, 95), gender (85, 86, 88–91, 94, 95, 97, 100, 101), area of residence (86, 89, 90, 94), and education level (83, 89–91, 94, 95, 98, 99, 101).

2. Income and economic issues: level of income (83, 85–87, 89, 91, 92, 94, 99–101), extent of government taxation (85), and employment status (88, 95, 99, 101).

3. Information level and information sources: awareness about the scheme (84, 92, 94, 98), knowledge regarding the scheme (87, 95), perceptions about financing healthcare (89, 95), insurance literacy, and access to the internet (100).

4. Illness and illness expenditure: illness condition and illness experiences (84, 86, 89, 93, 95, 98, 101), and previous healthcare expenditure (100).

5. Health service factors: availability of hospitals (100), type or ownership of usual healthcare provider (90), level of health facility to get treatment, in-patient or outpatient service (101), and quality of healthcare services (89, 90).

6. Factors related to financing schemes: scheme trust and preference (84), impression of paying much more (85), having alternative health insurance (86, 89, 92, 95), and class or level of health insurance plan (101).

7. Social capital and solidarity: religious affiliation (92), level of empowerment, group and network connection, and social cohesion and inclusion (93).

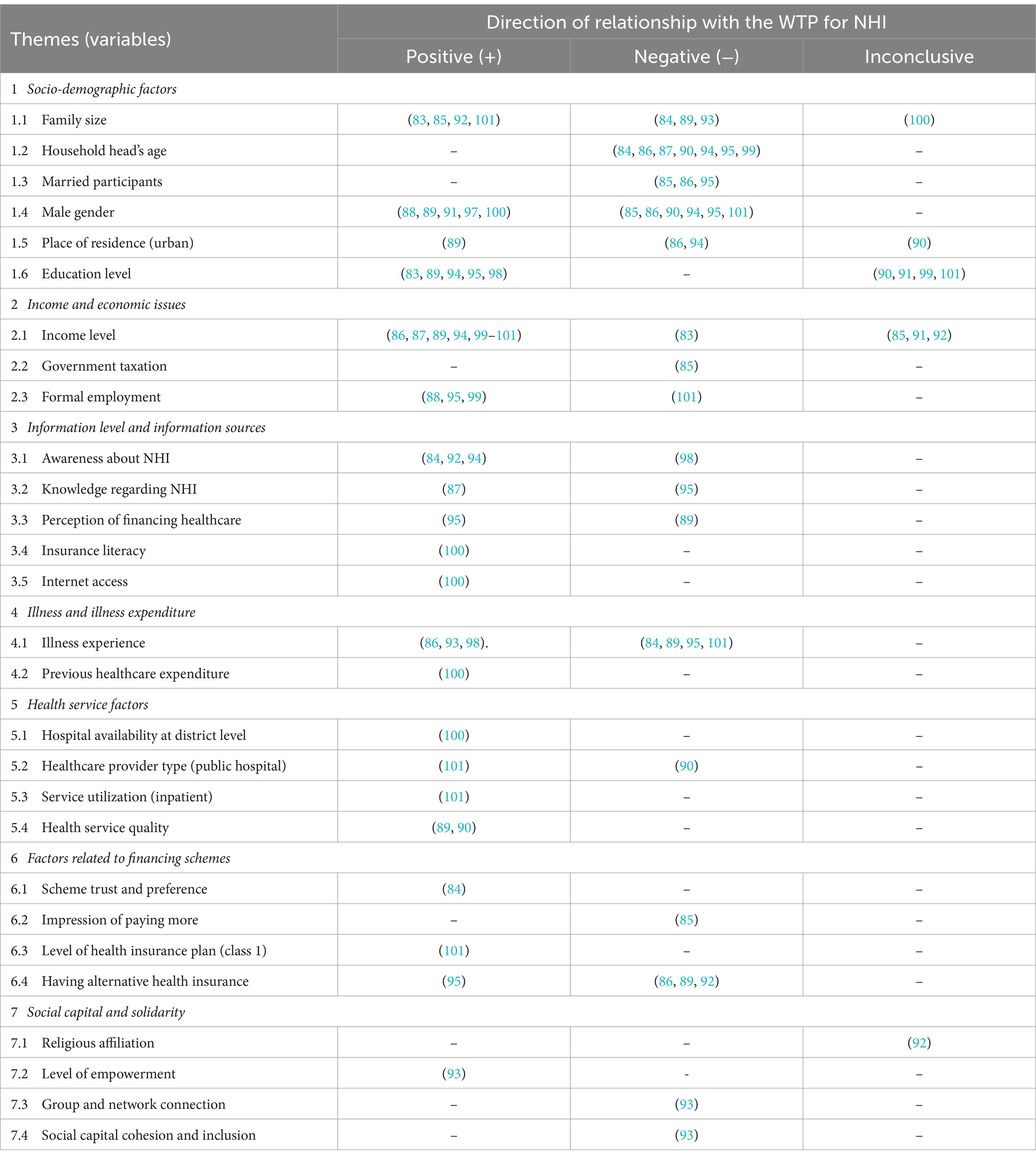

As demonstrated in Table 2, the included studies reported varying results concerning the relationship between the associated variables and the WTP for NHI. Despite these inconsistencies, some studies have found consistent outcomes. Specifically, the relationship of household age and marital status with WTP for the scheme has shown a negative relationship, meaning that the WTP decreases as age and married household heads increase.

Table 2. Direction of the relationship between the associated factors and the WTP for NHI.

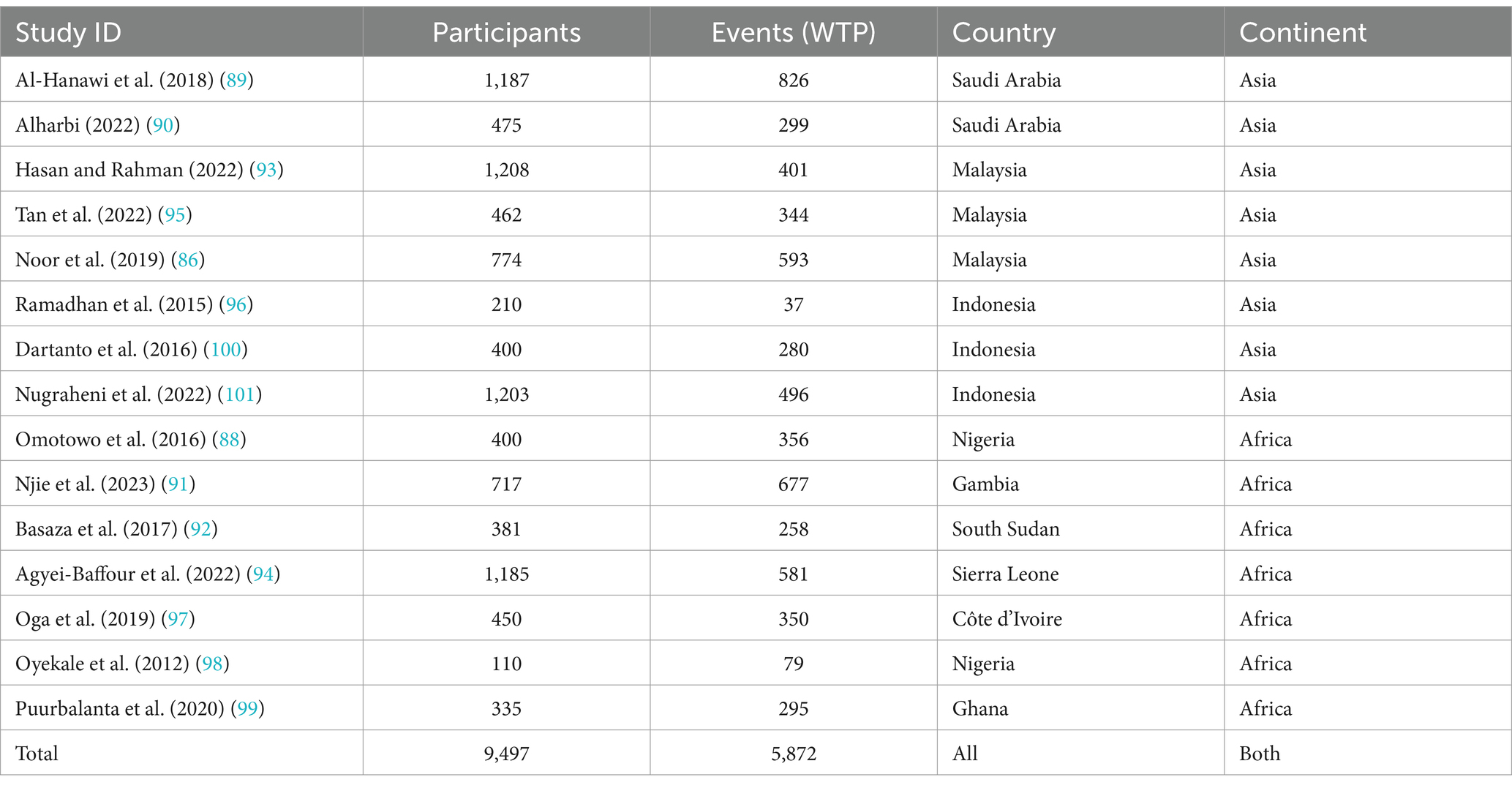

Quantitative synthesis Proportional estimation of the willingness to payFrom all the included studies, 15 records with a total of 9,497 participants were included in the quantitative synthesis (Table 3). Six of the eight included studies for the meta-analysis from Asia were conducted in Indonesia (n = 3) and Malaysia (n = 3), and the rest were conducted in Saudi Arabia (n = 2), while those from Africa were conducted in Nigeria (n = 2), Gambia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana. Most of the participants (62.3%) were from Asia, and the rest (37.7%) were from Africa.

Table 3. The frequency of the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia (n = 15), 2023.

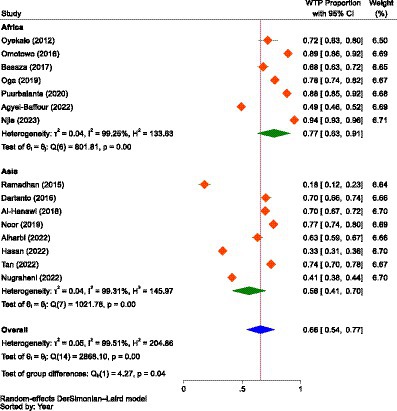

The combined (average) WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia was determined to be 66.0% (95% CI: 54.0–77.0%). The highest WTP for NHI was reported in Gambia at 94.0% (95% CI: 92–96%), while the lowest was reported in Indonesia at 18.0% (95% CI: 13–23%). The overall heterogeneity between studies was considerably high (102), with an I2 value of 99.51%. So, a random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled WTP for NHI (103). To identify the source of heterogeneity, as shown in Figure 4, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on continent, which showed significant difference between the subgroups (p = 0.039). According to the subgroup analysis, the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia, respectively, was 77.0% (95% CI: 63–91%) and 56.0% (95% CI, 41–70%). The studies conducted in Sierra Leone and Gambia reported the lowest and highest WTP for the scheme in Africa, at 49.0% (95% CI, 46.0–52.0%) and 94.0% (95% CI, 92.0–96.0%), respectively. In Asia, the lowest and highest WTP for NHI were found in Indonesia and Malaysia, with rates of 18.0% (95% CI, 13–23%) and 77.0% (95% CI, 74.0–79.0%), respectively.

Figure 4. The forest plot showing the proportions of the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia prior to excluding outliers (n = 15), 2023.

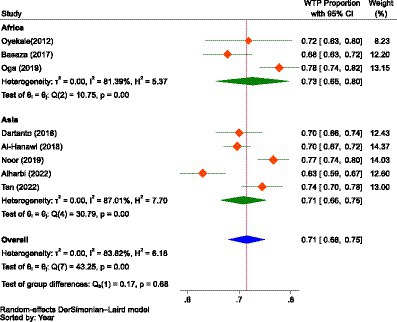

When the outliers were excluded, the difference between the subgroups was not found to be significant (p = 0.680), but still, the overall result showed that there was considerable heterogeneity between studies, with an I2 value of 83.82%, which was significant (p < 0.01). After removing the outliers, the WTP for NHI in Africa decreased from 77.0% (95% CI: 63–91%) to 73.0% (95% CI: 65.0–80.0%). Conversely, the WTP for the scheme in Asia increased from 56.0% (95% CI: 41–70%) to 71.0% (95% CI: 66–75%). The combined WTP for the scheme also rose from 66.0% (95% CI: 54.0–77.0%) to 71.0% (95% CI: 68–75%; Figure 5). Consequently, the difference in the WTP levels for the scheme between the two continents narrowed. Yet, Africa’s WTP was higher than that of Asia.

Figure 5. The forest plot showing the proportions of the subgroup analysis of the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia after excluding outliers (n = 8), 2023.

Factors influencing the willingness to payEight of the included studies reported binary outcomes regarding the influence of gender, previous illness, residence, alternative health insurance, awareness of the scheme, and the type of ownership of health facilities on the WTP for NHI. With respect to gender, two studies were from Africa and four were from Asia. About previous illness (five studies), type of ownership of facilities (two studies), and owning alternative health insurance (three studies), all studies were from Asia. Three studies, two from Asia and the other from Africa, reported about residence. Similarly, two studies, one in Africa and the other from Asia, reported awareness of the WTP for NHI. Since there was considerable heterogeneity (102) between studies and groups, we employed the DerSimonian and Laird (DL) method, which is recognized as the simplest and most widely used approach for applying the random effects model in metanalysis (104).

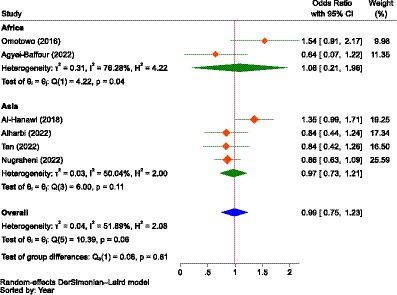

As demonstrated in Figure 6, the pooled estimate showed no difference between males and females concerning the WTP for NHI (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.75–1.23) in Africa (Nigeria and Sierra Leone) and Asia (Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Malaysia). Male participants in Africa were 1.08 times more likely to pay than female individuals (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 0.21–1.96), while in Asia, male participants were 3.0% less likely to pay for the scheme compared to female participants (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.73–1.21), indicating that gender had no significant influence on WTP for NHI.

Figure 6. The strength of the relationship between gender and the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia.

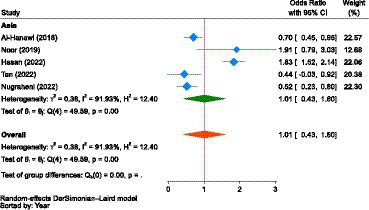

Regarding illness, as in the case of gender, the combined result showed that there was no significant difference between households with illness and those without (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.43–1.60) in terms of likelihood to pay for NHI in Asia (Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Malaysia). This indicated that having a previous illness did not significantly influence the WTP for NHI (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The strength of the relationship between experiencing illness and the WTP for NHI in Asia.

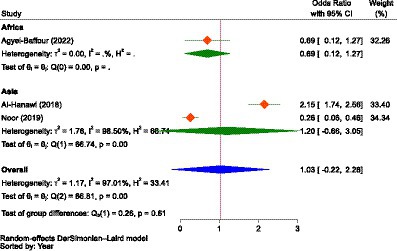

Concerning place of residence, the pooled estimate showed that participants living in urban areas were 1.03 times (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.09–1.98) more likely to pay for the NHI scheme than those living in rural areas in Africa (Sierra Leone) and Asia (Saudi Arabia and Malaysia); however, the relationship was not significant (Figure 8). Participants living in urban areas of Africa (Sierra Leone) were 31.0% less likely to pay for the scheme compared to their rural counterparts (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.62–0.76). In Asia (Saudi Arabia and Malaysia), urban residents were 1.20 times more likely to pay for the scheme (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: −0.65-3.06) than those living in rural areas.

Figure 8. The strength of the relationship between residence and the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia.

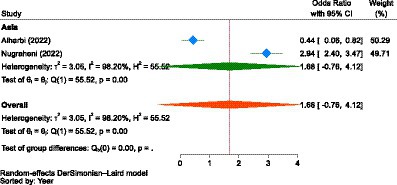

The other important factor was the type of ownership of a health facility in accessing healthcare. As portrayed in Figure 9, the estimate in Asia (Saudi Arabia and Indonesia) showed that those who used healthcare services at public health facilities were 1.68 times more likely (OR = 1.68, 95% CI: −0.76-4.12) to pay for NHI compared to participants who did not use services at public health facilities, indicating that the type of ownership of the health facility had no significant influence on the WTP for NHI.

Figure 9. The strength of the relationship between the type of health facilities to access health services and the WTP for NHI in Asia.

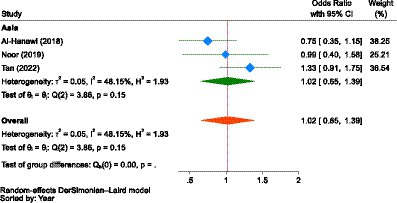

In Asia (Saudi Arabia and Malaysia), there was no significant difference between participants who owned PHI and those who did not (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.65–1.39) to pay for NHI. However, the association between ownership of having alternative health insurance and WTP for NHI was not significant (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The strength of the relationship between alternative health insurance ownership and the WTP for NHI in Asia.

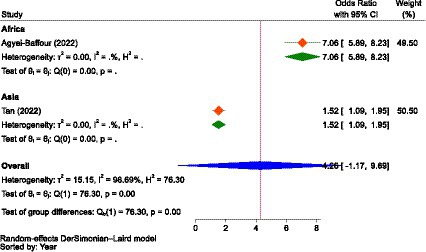

Though the strength of association was not significant, the combined result of two studies from Africa (Sierra Leone) and Asia (Malaysia) showed that participants with good awareness about the scheme were 4.26 times more likely to pay for it (OR = 4.26, 95% CI: −1.17–9.69) than those with poor awareness. However, in both individual studies or sub-groups, awareness had a significant relationship with the WTP for NHI (Figure 11). In Asia, individuals with good awareness were 1.52 more likely (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.49–0.83) to pay for NHI compared to those with poor awareness. Similarly, in Africa, those with good awareness were 7.06 times more likely (OR = 7.06, 95% CI: 5.89–8.23) to pay for it than their counterparts with poor awareness.

Figure 11. The strength of the relationship between the awareness level of participants about the scheme and the WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia.

Reporting bias and certainty of evidenceThe I2 statistic was used to measure between-study heterogeneity, which showed that the overall I2 value was greater than 50% (99.51%). To control the influence of each study on the combined result, measured as percentages of weights, a random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled WTP for NHI. To identify the source of heterogeneity, we conducted a test for the subgroup difference based on continents, which was significant (p = 0.039). To determine if there was publication bias between studies (asymmetry or the effect of small studies), we drew a Doi plot (Figure 12) that provided an LFK index of −1.67 and showed minor asymmetry.

Figure 12. A Doi plot to assess publication bias between the included studies.

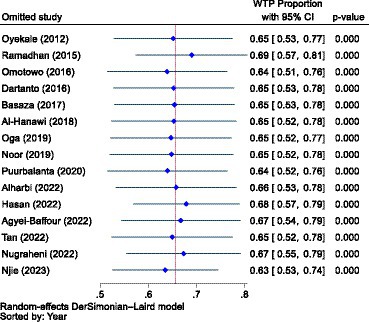

A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to identify outlier studies. Accordingly, seven studies were found to be outliers (88, 91, 93, 94, 96, 99, 101), and the pooled estimate (effect size) was influenced by the inclusion and exclusion of these studies. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 13, when we adjusted for outliers using a random effects model, all of the included studies (n = 12) were found not to be outliers. Therefore, we combined the data using a random effects model without excluding any outliers. Yet, the WTP for NHI was higher in Africa compared to Asia.

Figure 13. A sensitivity analysis to identify outlier studies from the included studies using the random effects model.

DiscussionDue to the diverse preferences of individuals, the WTP might be a very subjective measure of their intention to use health insurance. As a result, it might be affected by a variety of broad issues, like the nature of the healthcare market, information asymmetry, the psychosocial inclinations of individuals, the contexts in individual nations, the culture of a specific or defined community, health service valuation techniques or perceptions of peoples, the development level of countries, political dynamics and health policy, disease distribution and frequency, the quality of healthcare services, health system structure and taxation, reimbursement mechanisms, and the type of benefit packages to be covered, among others. The differences in the health systems of individual countries are perhaps the most crucial factors, as they shape the overall healthcare environment and are thus central to our well-being and livelihood. Should they collapse or experience disruption, it would impact the entire healthcare market and the overall sustainability of our economy (105). On the other hand, health insurance is not universally available in all developing countries, and the most cost-efficient approach to promoting health is unclear, which is a central policy concern in health economics (106). Furthermore, health insurance coverage varies greatly among different countries (107). Therefore, our discussion was not merely dependent on the specific results of this systematic review and meta-analysis; rather, we tried to deeply debate, compare, contrast, and comprehend various issues and evidence while being within the scope and context of our review and its findings.

Prevalence of the willingness to payThis systematic review and meta-analysis found that the pooled WTP for NHI in Africa and Asia was 71.0% (95% CI: 68–75%). Though the difference was not significant (p = 0.680), the WTP for the scheme in Africa (73.0, 95% CI: 65.0–80.0%) was higher than that in Asia (71.0, 95% CI: 66–75%). This is comparable to the findings of a primary study conducted in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, a Caribbean country, which reported that the WTP for NHI was 72.3% (108). From this evidence, one can easily extrapolate that the mean of the three percentages (73.0% in Africa, 71.0% in Asia, and 72.0% in Latin America) was 72.0%, which was approximately equivalent to the pooled WTP data mentioned above. This, in turn, indicates that the WTP for the scheme across the three continents was noteworthy, with minimal differences. Despite this appreciable WTP for NHI, the UHC on these continents, particularly in Africa and Asia, is still the lowest, and access to essential health services remains at a worrying level (109).

Chen et al. (110) noted that attaining UHC is difficult due to various factors globally and on these continents. Primarily, LMICs lack the funds required for UHC (110). As a result, OOP payments remained the single most common healthcare financing option in LICs, which can create a health protection gap (HPG) (111), a shortfall in finances to fund health expenditures (38). HPG is the portion of uninsured losses in total losses, or it is the sum of financially stressful OOP expenditures and the estimated cost of non-treatment due to unaffordability (111). In areas with weak financial protection, HPG, o

留言 (0)