Open defecation (OD) is the act of defecating in fields, forests, bushes, bodies of water, or other public areas without properly disposing of human waste (1). There can be different reasons for open defecation being practiced; it could be a voluntary, semi-voluntary, or involuntary choice (2). Most of the time, a lack of access to a toilet is considered the main reason. However, in some places, even people with toilets in their homes could prefer to defecate in the open area due to various factors, including poor construction and management of facilities, family size, educational status of owners, the presence of children, shortage of water supply, cleanliness of the toilet, personal preference, cultural taboos, and others (3–6).

Previous studies provide evidence and insights into anthropological-psychological factors like cultural taboos, cultural beliefs, gender dynamics, cleanliness perceptions, and lack of awareness that could hinder latrine utilization and underscore the importance of considering these perspectives in sanitation interventions and behavior change campaigns. For instance, a study by Sinha et al. in Odisha, India, highlighted the impact of taboos on latrine adoption. The researchers found that certain beliefs, such as the fear of evil spirits or ancestral deities being offended, hindered latrine utilization (7). Financial resources available in the community can enable households to invest in the maintenance and repair of their latrines, facilitate the upgrading of latrine facilities, such as adding handwashing stations or improving ventilation, which can enhance comfort and convenience, thereby promoting utilization (8).

Studies conducted in different parts of India showed that the level of open defecation practice among households with latrines was 54.8% in Dharmapuri District, 15% in Hubballi and Dharwad, and 45% in rural north India (4–6). In Ethiopia, the level of open defecation varies, with 16.9% in Wondo Genet District (9) and 27.8% in Machakle District, Northwest Ethiopia (2). A human excreta contains a large number of germs. When humans defecate in the open, flies feed on the waste and can carry small amounts of the excreta away on their bodies and feet, which causes contamination of the environment and the propagation of flies, which in turn causes the spread of diseases (8).

According to WHO estimates, 1.8 million people in low- and middle-income countries have severe trachoma (9), a primary cause of vision impairment that is carried by flies that spawn on human excrement and have a propensity to spread through an infected person's ocular discharge. The OD practice aids in the transmission of microorganisms that cause diarrheal diseases, and children are the most vulnerable (10). Globally, an estimated 2 billion cases of diarrhea occur each year, and 1.9 million children under the age of 5 years, mostly in developing countries, die from diarrhea (11). In Ethiopia in particular, diarrheal diseases alone accounted for 23% of the causes of child mortality (10). Moreover, OD can have social and cultural implications, including a loss of dignity and privacy. It can disproportionately affect women and girls, who face safety risks and reduced access to sanitation facilities, leading to compromised menstrual hygiene management and increased vulnerability to gender-based violence (12).

The presence of a latrine alone is insufficient to considerably reduce open defecation. To accomplish the process, people's behaviors at this contextual and individual level might need to change significantly (13). Studies in rural India revealed that households perceived open defecation as more convenient and time-saving if located far from their homes (14). Other studies in rural India identified that households practiced open defecation when latrines were overcrowded, unclean, or lacked privacy, indicating the influence of inadequate sanitation infrastructure (15). A previous study conducted in Ethiopia also showed that not attending formal education, having more than five family members, the presence of under-5-year-old children, preferring leaves as anal cleaning material, and having a latrine that needs maintenance influenced a household latrine and led to open defecation practices despite having a latrine (3).

Both governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have worked to build latrines and use them to achieve open defecation-free status using a variety of strategies, including the introduction of market-based sanitation (MBS) and community-led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH). The majority of the households (HHs) in the study site adopted these approaches. However, achieving and maintaining the status of open defecation-free was still challenging.

Even though plenty of studies were conducted on open defecation practices in general, the information on open defecation practices among households with latrine was scarce. To effectively create strategies for interventions and to completely eradicate open defecation, it is imperative to understand the factors that contribute to this paradoxical habit. Therefore, this study was aimed at assessing the open defecation practice and identifying the factors that contribute to the practice among households with a latrine in Ararso woreda, Jarar Zone, Somali region, Eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods Study design, area, and periodA community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among households with latrines in rural communities of Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, which is located in eastern Ethiopia, at 713 km east of Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). The district's overall population is 143,516, with 33,376 households. The district is divided into 17 administrative units (kebeles), of which five are urban and 12 are rural. In the district, there are 4 health centers and 10 health posts. The latrine coverage in the district was 31% (District Health Bureau annual report). The study was conducted from 10 to 27 September 2023.

PopulationsAll rural households with latrines in Ararso District were the source population, whereas rural households with latrines in the selected kebeles of the rural community of Ararso District during the study period were the study population.

Sample size determinationThe final sample of 632 households with latrines was estimated using the single population proportion formula by considering a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error (d), 27.8% population proportion of open defecation, which was taken from a study conducted in Machakl District, East Gojjam Zone (3), a design effect of 2, and a 5% non-response rate.

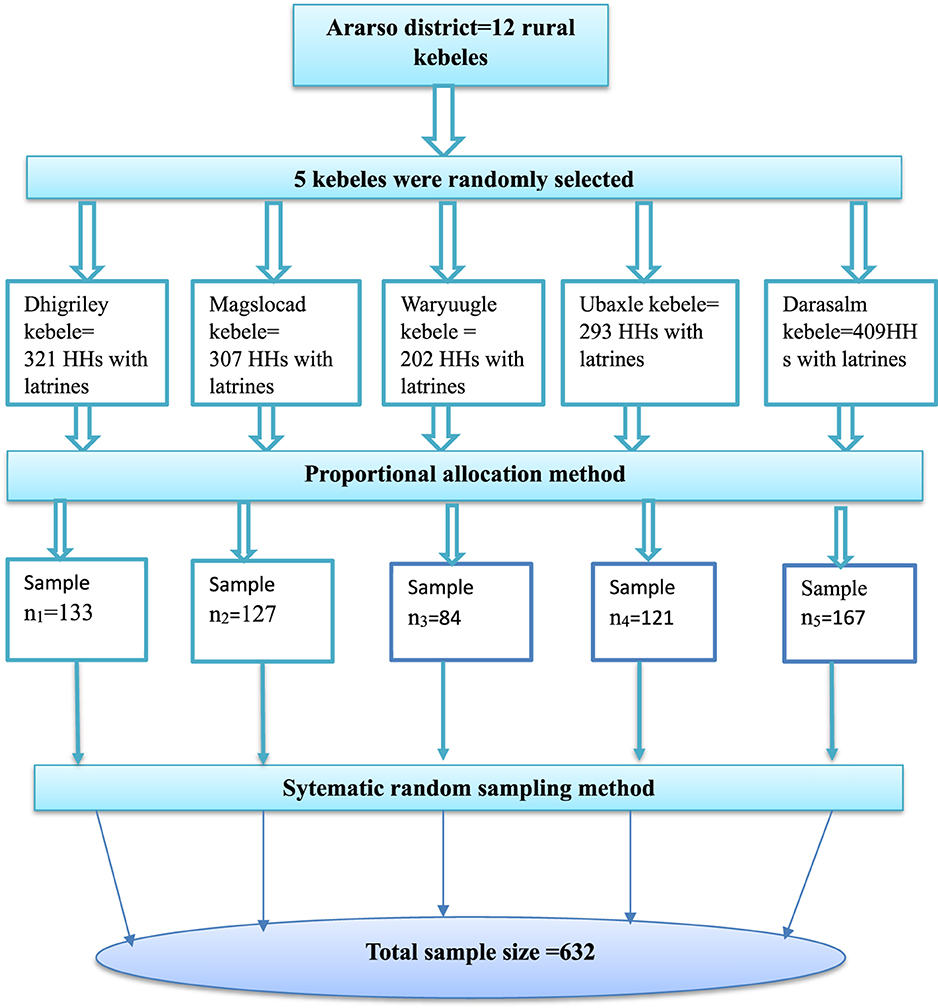

Sampling technique and proceduresThe sample was selected using a multistage sampling method. Five Kebeles were chosen from the district using a simple random sampling method. The sample size was proportionally allocated based on the number of households with latrines existing in each kebele. Finally, a systemic random sampling technique was employed with a Kth value of 2 to select households from selected kebeles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of sampling procedure in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023.

Data collection instruments and methodsThe data were collected using a structured questionnaire that was adopted after reviewing previous studies (3, 16, 17) and an observational checklist. The questionnaire was first prepared in English, translated into Somali language, and finally translated back into English by an expert who was fluent in both languages to maintain its consistency. The questionnaire was designed on the KoboToolbox—Humanitarian Response software platform (https://eu.kobotoolbox.org) and linked to the Kobo Collect version 2023.2.4 mobile application using the server URL (https://kc-eu.kobotoolbox.org), user name, and password for data collection. The data were collected using interviews and observation. Five college graduate professionals who had data collection experience using the Kobo Collect mobile application were involved in data collection. Two B.Sc. environmental health professionals were involved in supervising the data collection process.

Study variablesThe Open defecation practice was the outcome variable of this study, whereas socio-demographic factors (family size, gender, household educational status, marital status, occupational of household head, and the presence of students in the households); environmental or latrine-related factors (latrine type, service year of toilet, distance of toilet, hygienic condition of toilet, frequency of latrine cleaning, superstructure of latrine, and the availability of bushes, forests, beaches, and open spaces around the house); knowledge and attitude-related factors (personal attitude on open defecation practice, initiation of toilet use, knowledge on the effect of open defecation, and knowledge on the benefits of latrine use), and other variables (community norm, traditional belief, and taboo) were independent variables of this study.

Operational definition Open defecation practiceIn this study, open defecation practice was considered to be any household with latrines and at least one family member defecating either in fields, forests, bushes, open bodies of water, lakes, ponds, or other open spaces (17).

Knowledge on open defecation practiceThe response to knowledge questions about open defecation (OD) practice was summed up, and a total score was computed from 10 questions related to the hygiene effect on open defecation (OD). The respondents were considered to have good knowledge if they answered greater than or equal to the mean score (6.28) (6).

Attitude toward open defecation practiceIndividual attitudes toward open defecation were determined by 12 attitude questions using the Likert scale. All of the individual responses were added together to provide the score, and those who answered above the mean indicated a positive attitude toward open defecation (OD) practice, while those below or equal to the mean (36.7) indicated a negative attitude toward open defecation (OD) practice (3).

Traditional beliefsPeople's beliefs about latrine use, either negative or positive, six questions will be summed and mean (9.9) and above will be considered as having positive traditional beliefs otherwise negative (18).

TaboosWe considered open defecation taboo if the participants answered more than the mean (7.79) of the five questions asked; otherwise, it is not taboo (18).

Data quality controlA pretest was carried out on 5% of the selected households who had latrines in two kebeles in Degahbour Woreda other than the study area, which had similar socio-economic characteristics to the selected kebeles, to check its clarity before the actual data collection was carried out. The training was given to data collectors and supervisors for 2 days before actual data collection took place. The training was focused on how to fill out the questionnaire and how to approach the respondents. Supervisors performed close site supervision during the whole data collection period. The collected data were checked for completeness, consistency, accuracy, and clarity daily by the supervisors and principal investigator on the data server, and feedback was given for data collection throughout the progress of data collection.

Data analysisThe data were downloaded from the KoboTool Box—Humanitarian Response software server URL (https://kc-eu.kobotoolbox.org) in the Microsoft Excel format. Then, the data were cleaned, checked for its completeness, and exported to STATA version 14 for data analysis. Descriptive analyses like frequency distributions and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables were used to describe the characteristics of variables. The analyzed results were presented using texts, tables, charts, and graphs. Both binary logistic regression analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis were performed. In binary regression analysis, factors with a p < 0.25 were considered to have an association with the outcome variable. Then all variables that showed an association in binary logistic regression analysis at (p < 0.25) were considered for multivariate analysis to control all possible confounders and identify predictors of open defecation practice among households with latrines. Multicollinearity was checked with variance inflation factors (VIF). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, a p < 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance. An adjusted odd ratio along with a 95% CI was used to show the strength of the association between open defecation practice and associated factors. Model fitness was checked using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

Ethical considerationTo undertake this study, the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, provided ethical approval. A formal letter was submitted to the Ararso Wereda Health Bureau, and authorization was obtained to perform this study. The purpose of the study was clearly explained to participants, and all information acquired from them was kept in secrecy. Inform the participants that they are free to answer questions and end the interview at any time. Finally, the participants provided informed consent for their participation in the study.

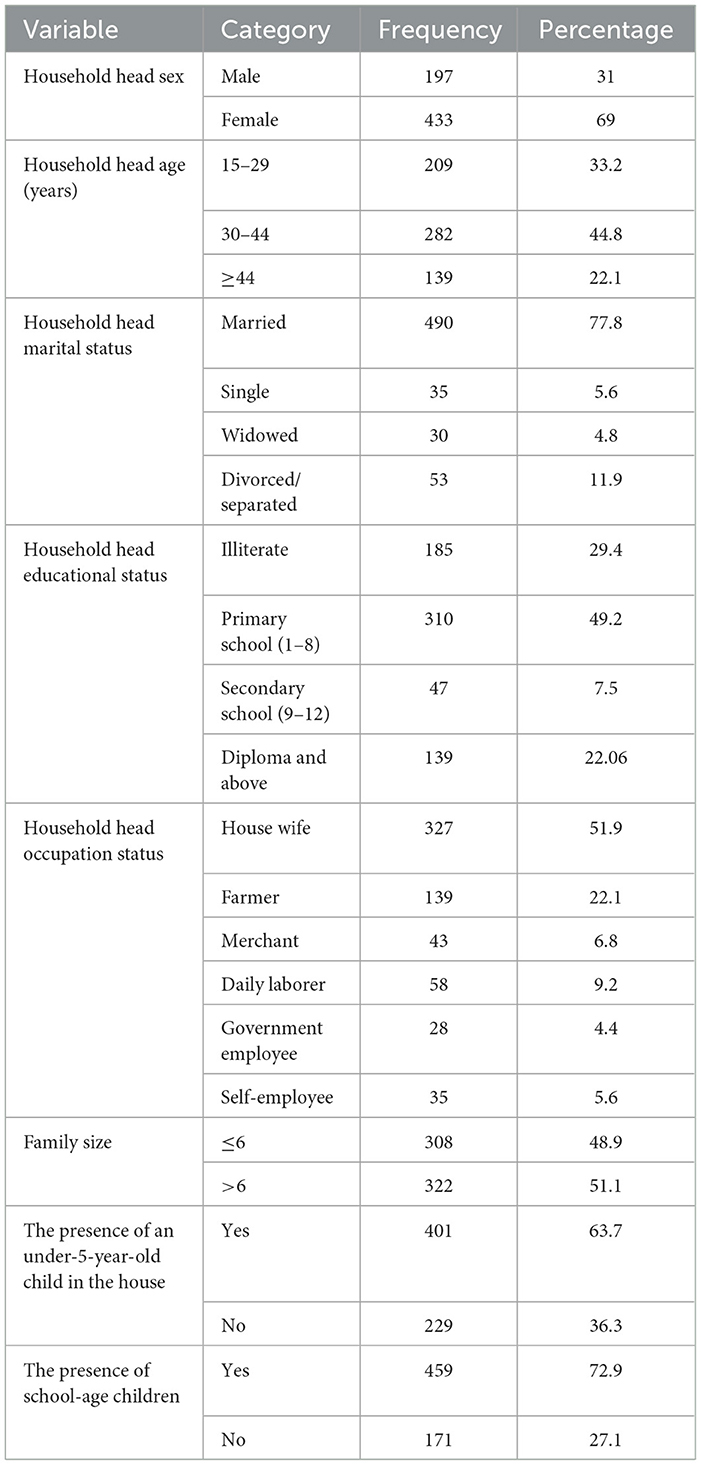

Results Socio-demographic characteristics of householdsA total of 630 households from five kebeles in the Ararso District were included in the study, resulting in a response rate of 99.7%. Out of these, 433 (69%) household heads were female. The mean age of the HH heads was 35.62 years, with a standard deviation (±SD) of 10.34 years. Regarding the marital status of the HH heads, 490 (78%) were married. Of these, 327 (52%) of the HH heads were wives. Nearly half, 322 (51%) of the households, had a family size greater than six, whereas about 401 (64%) of the HHs had under-5-year-old children. The majority, 459 (73%) HHs, had school-age children (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

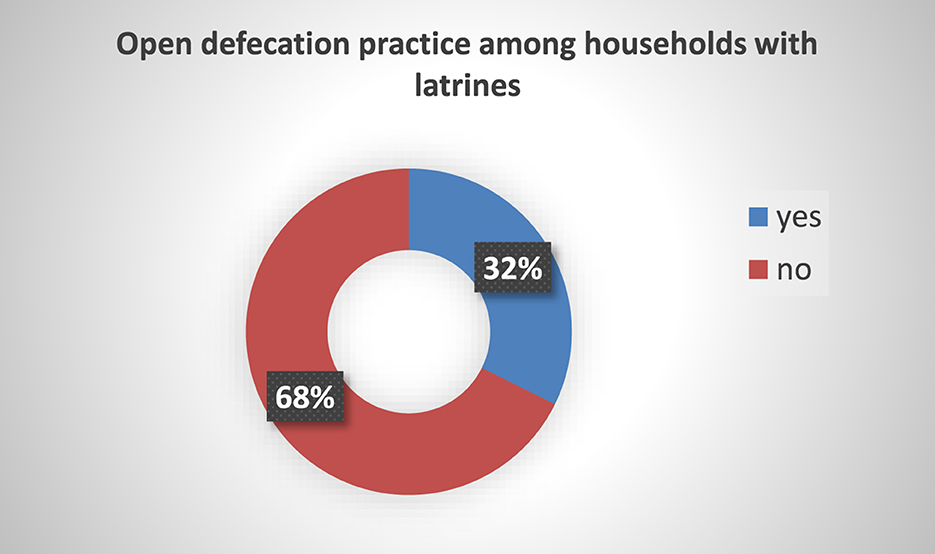

Open defecation practices among households with latrineOut of the 630 households (HHs) included in the study, 204 (32.4%) reported practicing open defecation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Open defecation practice of HHs with latrines in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

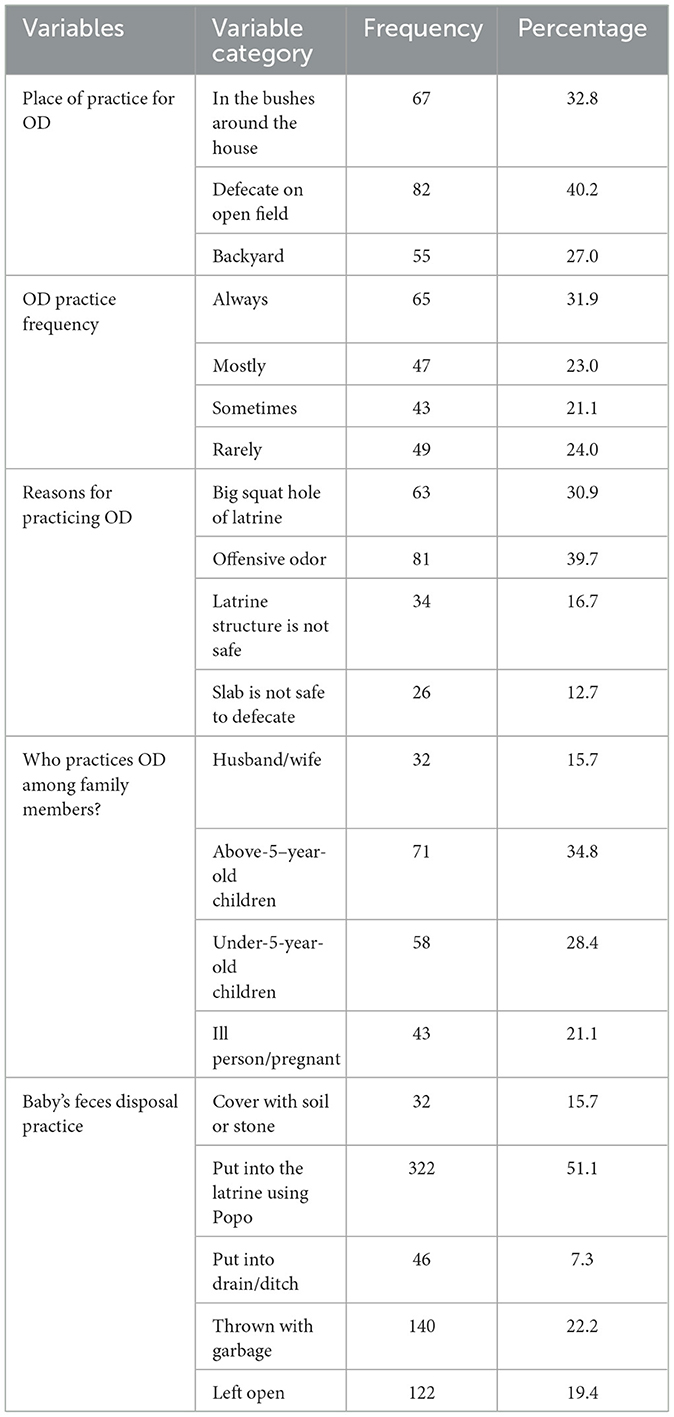

Among the participants who practiced OD, 67 (32.8%) respondents stated that they defecated in the nearest bushes or open spaces around the house. Of these, 31.9% of households always practiced open defecation. Among those practicing OD, 41 (30.9%) mentioned the large squat hole of the latrine, and 81 (39.5%) stated the offensive odor from the latrine as a factor that pushed them to defecate outdoors. Also, among those practicing OD, 58 (28.4) were under-5-year-old children. Regarding households with babies, 322 (51%) households disposed of their baby's feces into latrine using Popo (Table 2).

Table 2. Open defecation practice and child feces disposal practice among family members in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 204).

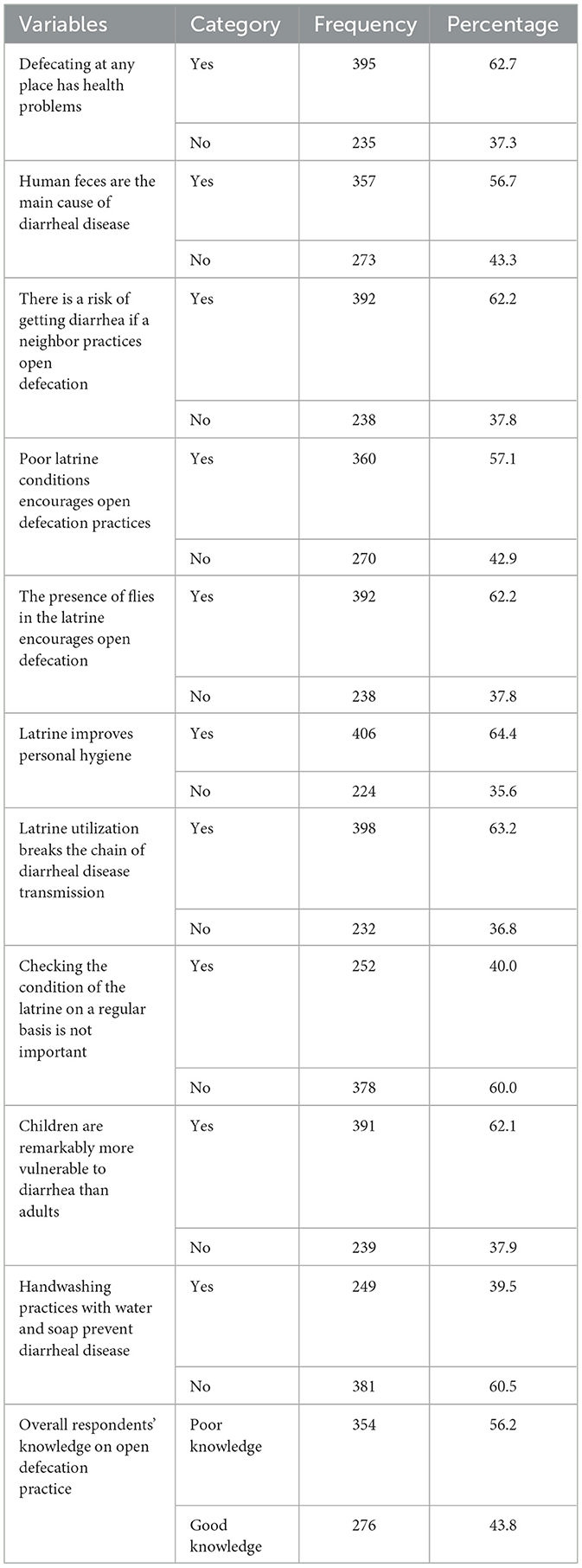

Knowledge of respondents on open defecation practiceOut of 630 participants, 395 (62.7%) respondents reported that defecating in any place had health problems, and 357 (56.7%) respondents knew that human feces were the main cause of diarrhea. Notably, 360 (57.1%) respondents said that poor latrine conditions encouraged open defecation, and 406 (64.4%) reported that household latrine improved personal hygiene. In total, 398 (63.2%) reflected that latrine had an effect on increasing overall family health and breaking the chain of disease transmission, and 249 (39.5%) of the respondents reported that handwashing with soap and water could prevent diarrheal disease. Regarding the respondents' knowledge of OD, 354 (56.2%) of the study subjects had poor knowledge (Table 3).

Table 3. Knowledge of respondents on open defecation practice among households with latrines in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

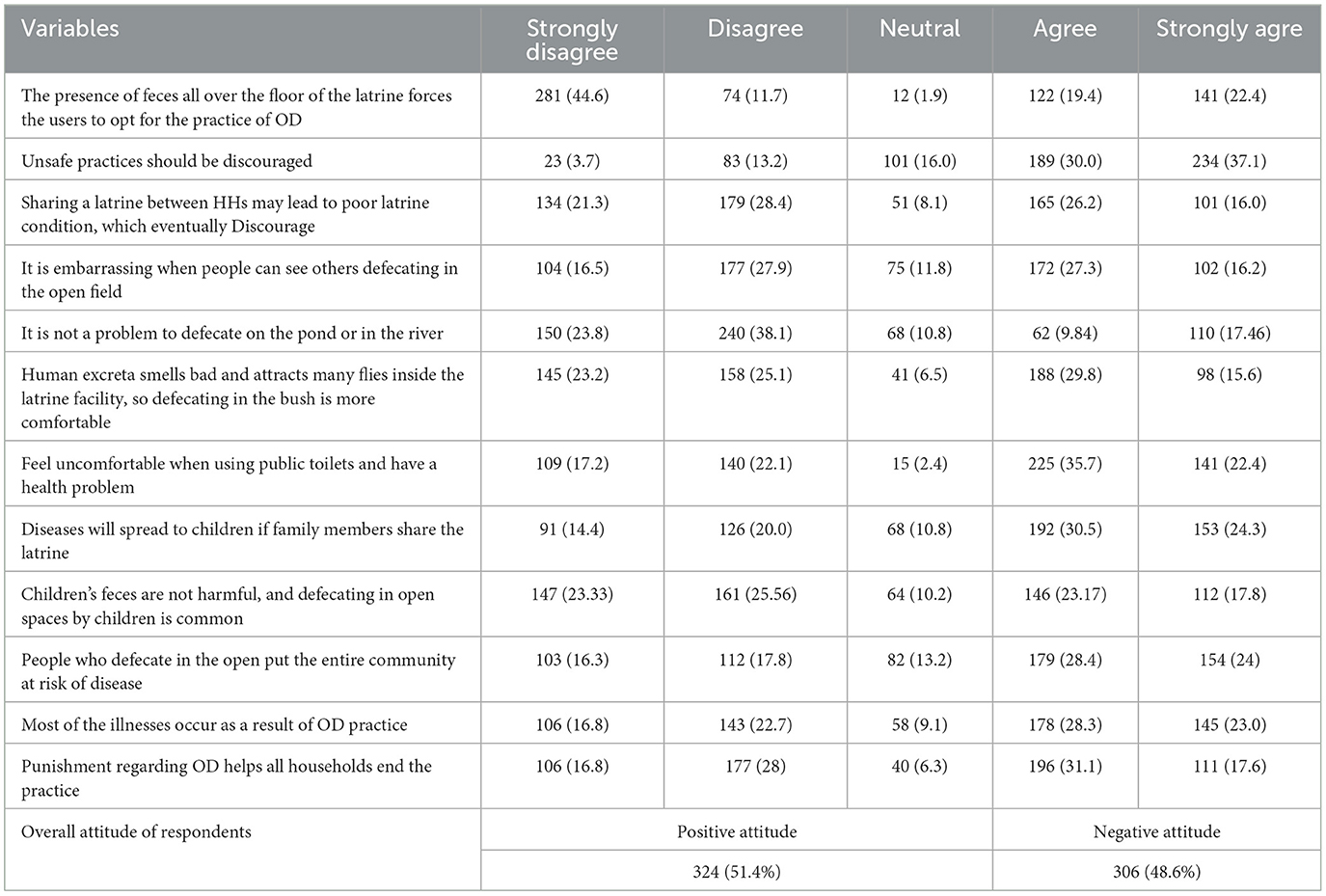

Attitudes of respondents toward open defecation practiceIn total, 281 (44.6%) respondents strongly believe that the presence of feces all over the floor of the latrine forced users to opt for the practice of OD, whereas 172 (27.3%) respondents thought that it was embarrassing when people could see others defecating in the open. Notably, 240 (38.1%) respondents disagreed that defecating on the pond or in the river was not a problem. In addition, 143 (22.7%) respondents disagreed that the majority of illnesses were caused by OD practice, while 196 (31.1%) respondents agreed that punishment for OD helps all households discontinue the practice. Almost half, 324 respondents (51.4%), had a positive attitude toward OD practice, while 306 (48.6%) had a negative attitude (Table 4).

Table 4. Attitude of respondents on open defecation practice in Ararso district, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

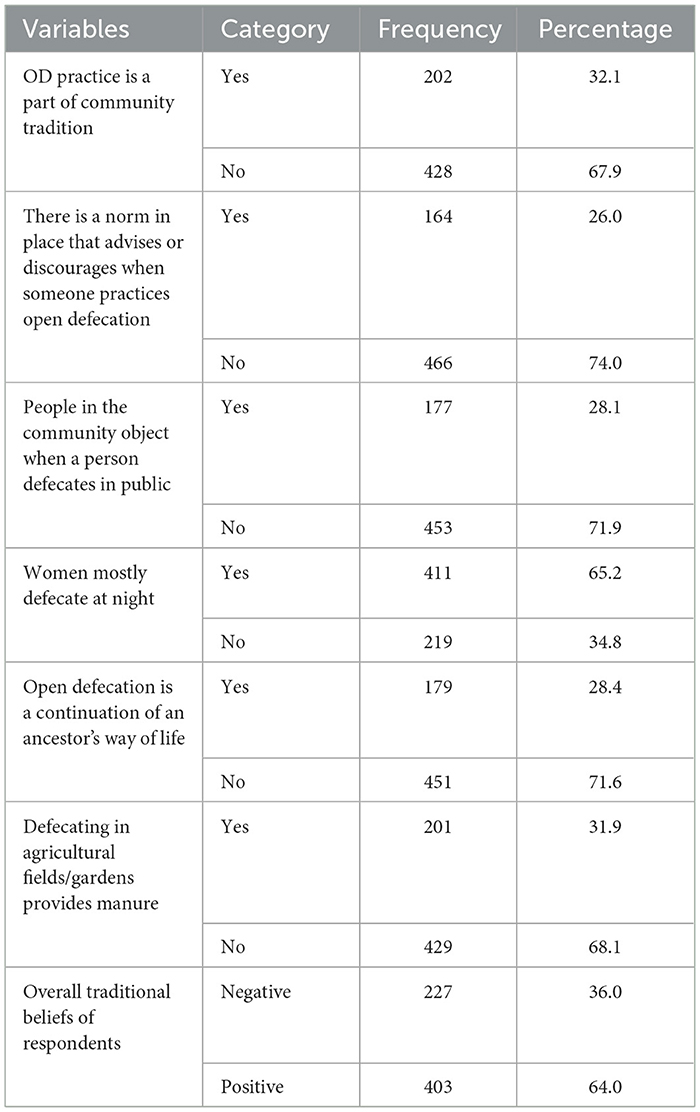

Socio-cultural, behavioral characteristics, and traditional belief questionsAmong 630 respondents, 428 (67.9%) stated that the practice of OD did not violate their tradition, and 466 (74%) stated that there were no punishments associated with OD in their village. Notably, 411 respondents (65.2%) preferred to defecate at night. Furthermore, 429 (68.1%) of respondents stated that OD practice did not provide manure for agricultural activities. In addition, 453 (71.9%) respondents said that no one objected when someone practiced OD. Generally, 403 (64%) had a positive traditional belief about open defecation practice, whereas 227 (36%) had a negative traditional belief (Table 5).

Table 5. Socio-cultural characteristics of respondents on OD practice in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

Socio-cultural and behavioral characteristics taboo-related questionsOf the 630 respondents, 277 (36%) stated that there was a taboo for defecating in an enclosed space (toilet). On the contrary, 229 (36.3%) respondents claimed that menstruating girls defecating in the toilets used by family members were forbidden. Similarly, 345 (54.8%) respondents claimed there was no taboo in sharing a latrine with a mother-in-law or father-in-law, 352 (55.9%) said there was no taboo associated with using a latrine with a son-in-law or daughter-in-law, and 335 (53.2%) reported that practicing OD was considered taboo (Table 6).

Table 6. Socio-cultural characteristics of respondents on OD practice in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

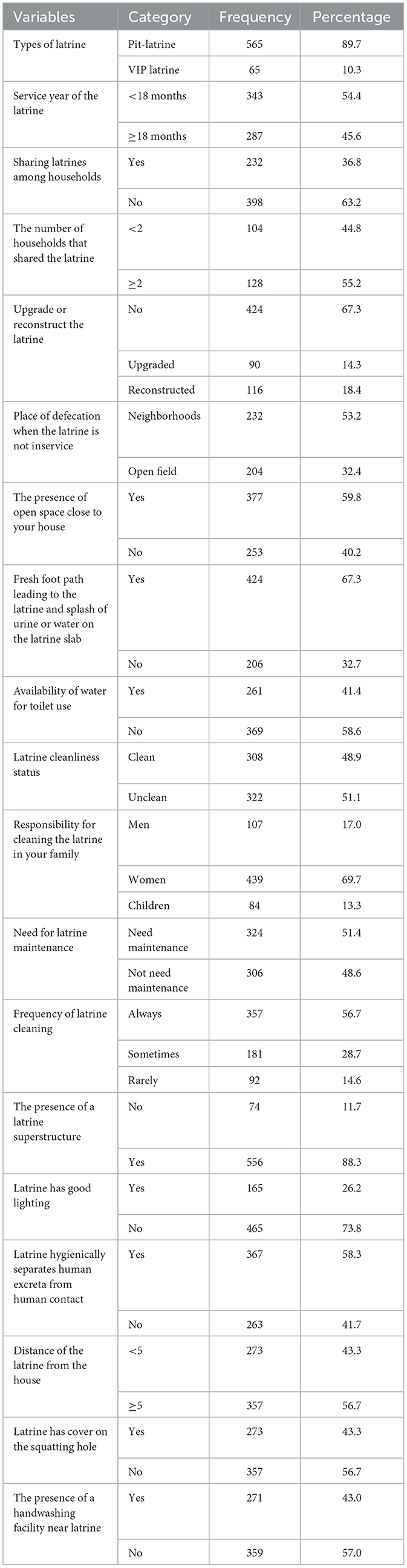

Environmental or latrine-related factorsThe majority, 565 (89.7%), of the households had pit latrines. Almost half, 343 (54.4%) of the latrines, were built < 18 months before the study period. Only 240 (36.8%) families shared a latrine with others. Of these, 128 (55.2%) households shared a latrine with more than two other households. On the other hand, 118 (16.4%) of the latrines were completely reconstructed. Out of 632 households interviewed, 204 (32.4%), used open fields near their houses while the latrine was not in service. Notably, 377 (59.8%) respondents said that there was open space near their home. In all, 424 (67.3%) latrines had a fresh footpath leading to the toilet, and there was a splash of urine or water on the latrine's surface. Only 261 (58.6%) households received water for toilet usage, and 336 (53.3%) latrines were not clean. In 439 (69.7%) households, women were responsible for cleaning latrines, while 357 (56.7%) households always cleaned their latrines. Of the 630 latrines, 324 (51.4%) required maintenance. The majority of the latrines, 556 (88.3%), had superstructures. Furthermore, 357 (56.7%) of the latrines were located more than five meters away from the dwellings. In addition, 357 (56.7%) latrines lacked a cover for the squatting hole, while 359 (57%) had a handwashing facility near the latrine (Table 7).

Table 7. Environmental or latrine-related factors in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

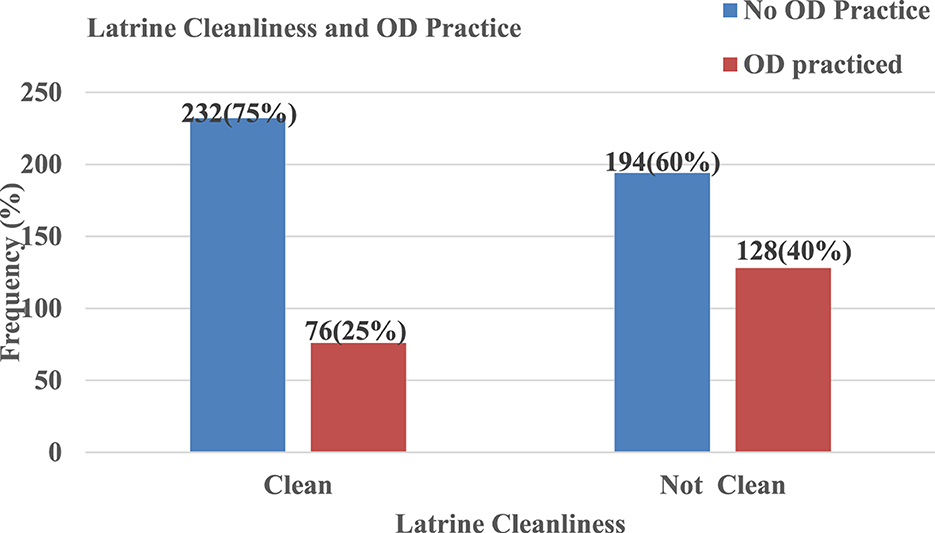

A three-fourth of HHs with clean latrines did not practice OD, whereas 40% of HHs with unclean latrines practiced OD (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Open defecation practice and cleanliness of latrine in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Ethiopia, 2023.

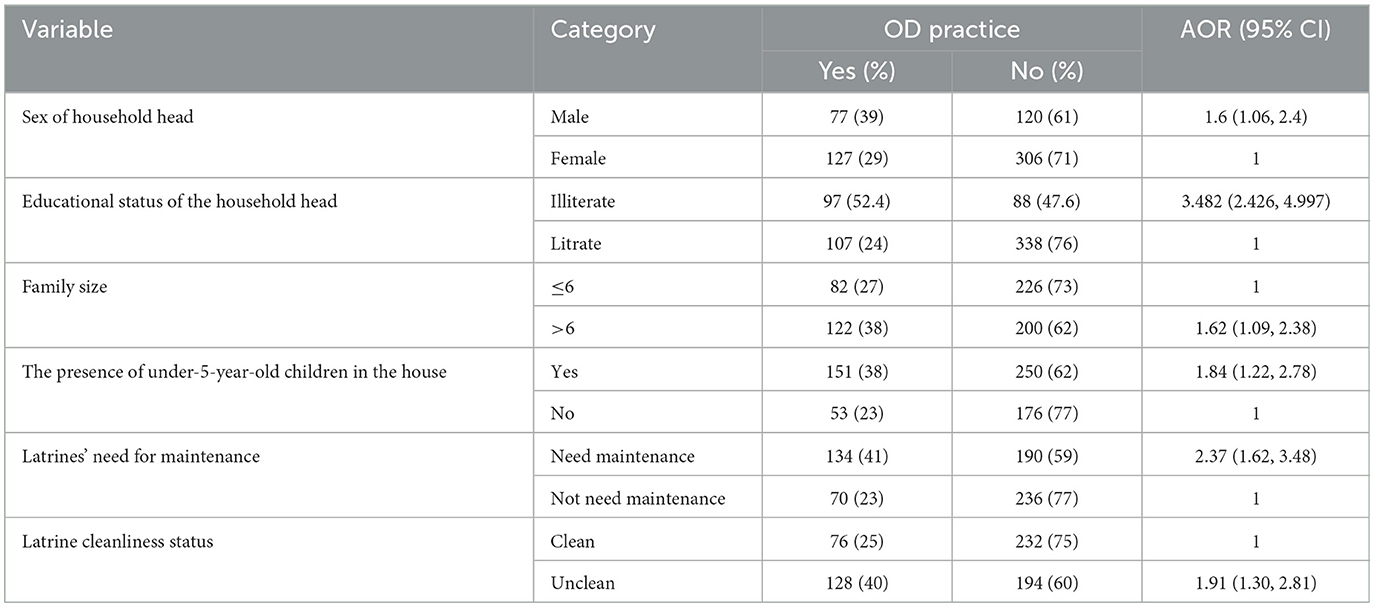

Factors associated with open defecation practices among households with latrinesIn multivariable logistic regression, sex of respondents, educational status of household head, family size, educational status of household head, the presence of under-5-year-old children in the house, need for latrine maintenance, and latrine cleanliness status were significantly associated with open defection practice at p ≤ 0.05.

Accordingly, being men increased the likelihood of open defecation practice by 60% as compared to females (AOR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.4). The odds of open defecation practice among household heads who were illiterate were 3.5 times (AOR = 3.482; 95% CI: 2.426, 4.997) higher than literate household heads. The odds of open defecation practice increased by 62% among households with more than six members as compared to households with less than six members.

(AOR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.09, 2.38). The odds of open defecation practice were 1.84 times higher among households with under-5-year-old children as compared to households without under-5-year-old children (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.22, 2.78). The odds of open defecation practice were 2.37 times (AOR = 2.37, 95% CI: 1.62, 3.48) higher among households with latrines that needed maintenance as compared to households that did not need maintenance. Furthermore, the odds of open defecation practice were 1.91 times (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.30, 2.81) higher among households with unclean latrines than those with clean latrines (Table 8).

Table 8. Factors associated with open defecation practice among HHs with latrines in multivariable logistic regression analysis in Ararso District, Jarar Zone, Somali Region, Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 630).

DiscussionThe current study revealed that 32.4% of the rural households with latrines practiced open defecation. The findings of this study were slightly greater than those of the studies conducted in Machakle District, Northwest Ethiopia (27.8%), Wondo Genet District (16%), Raipur District, India (23.3%), and Kurnool District, India (27.6%) (2, 6, 19, 20). On the other hand, the prevalence of open defecation in this study was lower than in studies conducted in Southwest Ethiopia, Aneded District, Northwest Ethiopia, and South India, where 64.1%, 37%, and 54.8% of households with latrines practiced open defecation, respectively (4, 20, 21). The variations in the prevalence of open defecation practice among households with latrines might be due to awareness about latrine utilization among communities, socio-demographic characteristics within communities, differences in the sample size, and the year of the study. However, the finding of this study was consistent with a study conducted in rural districts of India, where 31% of households with latrines practiced open defecation (4).

Community latrine utilization is influenced by local culture and traditional beliefs. In the study area, 53.2% of respondents said that the presence of taboos in the communities discourages people from defecating or urinating in latrines, 36% had negative beliefs about toilet use, and 48.6% had a negative attitude toward latrine use. The findings were backed by a study conducted in Wonago District, southern nations, Ethiopia, and Borena, Ethiopia (22, 23). Cultural taboos, superstitions, attitudes, and religious beliefs can all have an impact on the acceptance and continuous use of improved latrines in rural areas. In rural areas, some tribes link latrines with impurity or badness, and they avoid defecating and urinating in latrines. In certain rural areas, menstrual women are not permitted to use the same latrine as men, and sharing a toilet between men and women is considered an obscenity (24). When questioned further, rural communities discovered that poor menstruation hygiene by women in rural communities is the cause of this condition (24).

In this study, the odds of open defecation practice were 1.60 times higher among men as compared to women, and the finding was in line with the study conducted in Chhattisgarh, India (25, 26). In Ethiopia, men engaged more in outdoor activities than females. Furthermore, the culture of the community encourages men to stay outside, far from home, for various outdoor activities such as farming, which does not allow them to be around the house where there are latrines. On the other hand, the culture and tradition prevent women from practicing open defecation because the community considers a lot of the women's behavior that is evaluated for marriage and other socially important conditions. That is why women are highly guarding their privacy and reputation.

In this study, the level of education was significantly associated with open defecation practice. The odds of open defecation (OD) were 3.482 times higher among household heads who were illiterate compared to literate household heads. This result was consistent with the study conducted in Chencha District, Southern Ethiopia, Chiro Zuria District, and West Harerghe Zone, Ethiopia (26, 27). This might be due to educated households having greater access to sanitation and hygiene information than illiterate households. As a result, educated households used their latrine facilities more than illiterate households.

Family size was significantly associated with open defecation practices. The odds of open defecation practice were 1.68 times higher among family sizes greater than six compared to family sizes less than six. This finding was in line with a study conducted in Addis Ababa (28). The reason might be that households with more family members lead to queuing for the latrine, and anyone who cannot wait for the toilet has a higher tendency to practice open defecation. Furthermore, higher family members reduced the cleanliness of the toilet, and when the toilet became dirty, individuals were forced to defecate outside.

The presence of under-5-year-old children within households was significantly associated with open defecation practices. The odds of open defecation (OD) practice were two times higher among households with under−5-year-old children compared to those households without under-5-year-old children. This result was in line with the studies done in Dembia District, Wondo Genet District, southwest Ethiopia, and eastern Nepal (6, 20, 29). The possible justification was that under-5-year-old children cannot use the toilet, and when the urge to defecate comes, they defecate openly if there is no one around to give them popo. Also, parents do not emphasize the open defecation of the children, but rather adults.

Latrines' need for maintenance was significantly associated with open defecation practices. The odds of open defecation (OD) practice were 2.34 times higher among households having latrines that required maintenance as compared to those households' latrines that did not need latrine maintenance. This result was in agreement with the study conducted in Wondo Genet and southwest Ethiopia (6, 20). This might be due to households with unmaintained latrines reflecting various problems such as leakage, privacy issues, and a lack of comfort that may hinder their use. Also, unmaintained and deteriorated latrines will expose them to different accidents, like falling. These conditions pushed some household members to defecate in the open, especially where there are opportunities for them to practice open defecation.

Furthermore, the practice of open defecation in the study area was significantly associated with the latrine cleanliness status. The odds of open defecation practice were 1.96 times higher among households with unclean latrines compared to those with clean latrines. This study was in line with the studies done in Dembia District, Aneded District, North West Ethiopia, and Laelai Maichew Woreda, Aksum, Tigray, Ethiopia (21, 30). This might be due to the user's fear of using contaminated, breeding sites of fly, unclean, odorous, and dirty toilets. People prefer and are motivated to use a clean and attractive latrine. For this reason, individuals prefer defecating in an open environment rather than using a dirty toilet.

ConclusionEven though every household had a latrine, open defecation was common in the study area. In total, 32.4% of households with latrines experience open defecation in outdoor environments. The sex of the household head, family size, the presence of under-5-year-old children in the household, the need for latrine maintenance, latrine cleanliness status, and the educational status of the household head were significantly associated with open defecation practice. In conclusion, toilet coverage was high in the study area, but the presence of a latrine facility alone may not be sufficient to eliminate open defecation practice without addressing factors that encourage the practice. As a result, the Ararso District Health Bureau must give attention to the above-identified factors to reduce OD open defecation practices among households with latrines through appropriate design of sanitation and hygiene promotion. Health extension workers must closely follow the community found remote from health posts to undertake sanitation and hygiene education promotion that improves toilet utilization behavior, particularly among women who likely spend the majority of their time caring for their children.

Data availability statementThe raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statementTo undertake this study, the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University provided ethical approval. The participants provided informed consent for their participation in the study.

Author contributionsAI: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. MI: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. AG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DA: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. AC: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank the Jarar Zone Health Bureau and the Ararso District Health Office for their support and collaboration throughout this research project. Finally, we would like to acknowledge data collectors, supervisors, study participants, and questionnaire translators for their efforts in making this study successful.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbbreviationsAOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; OD, Open defecation; SDG, Sustainable Development Goals; CI, Confidence Interval; CLTSH, Community Leads Total Sanitation and Hygiene; HEP, Health Extension Program; HHs, Households; JMP, Joint Monitoring Program; MBS, Market Basic Sanitation; UNICEF, United Nations Children's Emergency Fund; WHO, World Health Organization; NGO, Non-Governmental Organization.

References2. Abathun T. Open Defecation Practice and Associated factors Among Households who have A Latrine in Rural Communities of Machakl District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Northwest, Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross Sectional Study. (2020).

4. Yogananth N, Bhatnagar T. Prevalence of open defecation among households with toilets and associated factors in rural south India: an analytical cross-sectional study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. (2018) 112:349–60. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/try064

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Bathija GV, Sarvar R. Defecation practices in residents of urban slums and rural areas of hubballi, Dharwad: a cross sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health. (2017) 4:724–8. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20170747

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Ashenafi T, Dadi AF, Gizaw Z. Latrine utilization and associated factors among Kebeles declared open defecation free in Wondo Genet district, South Ethiopia, 2015. ISABB J Health Environm Sci. (2018) 5:43–51 doi: 10.5897/ISAAB-JHE2018.0050

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Sinha A, Nagel CL, Thomas E, Schmidt WP, Torondel B, Boisson S, Clasen TF. Assessing latrine use in rural India: a cross-sectional study comparing reported use and passive latrine use monitors. Am J Tropical Med Hyg. (2016) 95:720. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0102

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Jenkins MW, Scott B. Behavioral indicators of household decision-making and demand for sanitation and potential gains from social marketing in Ghana. J Social science medicine (Baltimore). (2007) 64:2427–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.010

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Fenta A, Alemu K, Angaw DA. Prevalence and associated factors of acute diarrhea among under-five children in Kamashi district, western Ethiopia: community-based study. BMC Pediatr. (2020) 20:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02138-1

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Suthar P, Joshi NK, Joshi V. Study on the perception of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and attitude towards cleanliness among the residents of urban Jodhpur. J family Med Prim Care. (2019) 8:3136–9. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_502_19

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Patil SR, Arnold BF, Salvatore AL, Briceno B, Ganguly S, Colford JM. Jr., et al. The effect of India's total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors and child health in rural Madhya Pradesh: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. (2014) 11:e1001709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001709

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Coffey D, Gupta A, Hathi P, Khurana N, Spears D, Srivastav N, et al. Revealed Preference for Open Defecation: evidence froma new survey in rural North India. Econ Political Weekly. (2014) 49:43–55. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24480705

15. Temesgen A, Molla Adane M, Birara A, Shibabaw T. Having a latrine facility is not a guarantee for eliminating open defecation owing to socio-demographic and environmental factors: the case of Machakel district in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0257813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257813

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Supply WUJW, Programme SM. Progress on drinking water and sanitation: 2014 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2014).

17. Lemma T, Abera K, Sintayehu BH, Hailu FD, Mesfin TS. Latrine utilization and associated factors among kebeles implementing and non implementing urban community led total sanitation and hygiene in Hawassa town, Ethiopia. African J Environm Sci Technol. (2017) 11:151–62. doi: 10.5897/AJEST2016.2223

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Panda PS, Chandrakar A, Soni GP. Prevalence of open air defecation and awareness and practices of sanitary latrine usage in a rural village of Raipur district. Int J Comm Med Public Health. (2017) 4:3279–82. doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20173828

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Oljira D, Berkessa T. Latrine use and determinant factors in Southwest Ethiopia. J Epidemiol Public Health Rev. (2016) 1:1–5. doi: 10.16966/2471-8211.133

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Chanie T, Gedefaw M, Ketema K. Latrine utilization and associated factors in rural community of Aneded district, North West Ethiopia, 2014. J Community Med Health Educ. (2016) 6:1–12. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000478

留言 (0)