Palliative care is an essential aspect of healthcare that focuses on improving the quality of life of individuals with serious health-related suffering.[1] The World Health Organization defines palliative care as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering’.[2] Palliative care is an essential element of universal health coverage.[3] Addressing the need for palliative care and pain relief to achieve the target of 3.8 of sustainable development goal.[4] Patients with life-threatening or life-limiting health conditions often experience gaps in continuity of care, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where healthcare systems are frequently overburdened by high demand for services. Community-based palliative care represents a potential solution to address this issue by providing a means to ensure continuity of treatment for individuals with terminal illnesses. Estimating the demand for palliative care is a critical step towards ensuring the provision of quality palliative care services.

Globally, it is estimated that 56.8 million people require palliative care annually, with the majority of adults in need of palliative care and children living in LMICs.[5] This estimation is based on modelling done on data from the Global Burden of Disease Study for 20 diseases plus injury. In India, where the burden of chronic illnesses is high,[6] palliative care services are essential for the provision of holistic care to patients and their families. Several studies in India have reported the need for palliative care in the community setting but varies from 1.5/1,000 population[7] to 43.1/1,000 population.[8] Accurately estimating the need for palliative care and identifying vulnerable groups are crucial steps in prioritising palliative care services and achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3.8. This study aimed to systematically review the existing literature and conduct a meta-analysis to estimate the need for palliative care services in India. By providing an estimation of the need for palliative care services, our study holds the potential to guide the development of targeted policies and improve programmes to address the specific palliative care needs of India.

MATERIAL AND METHODS Research question and selection criteriaOur primary outcome of interest was the need for palliative care among the population of India, which we estimated using summary statistics. Our inclusion criteria involved community-based (population/school-based) studies that assessed the need for palliative care, any study design, conducted in India, studies written or translated to the English language, and published from their inception until the last date of search 30th April 2023. We excluded studies that were conducted solely in hospitals or studies which included only diseased patients to avoid Berksonian bias, we also excluded studies that reported secondary data or review articles or were not conducted on humans.

Search strategyTwo independent authors (AC and AD) conducted the search and independently screened the articles. They evaluated the full-text articles that met the eligibility criteria. In the event of any discrepancies, the authors engaged in discussions to reach a consensus. If they were unable to reach a consensus, the third author (BN) intervened to resolve any outstanding issues. We conducted a comprehensive search for relevant studies by examining various databases including PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and EBSCO Host. We also screened the first 20 pages of Google Scholar. We used keywords such as ‘Palliative care,’ ‘end of life care,’ ‘terminal care,’ ‘hospice care’ and ‘Community,’ ‘Population’ or ‘Cohort,’ and refined our search by incorporating MeSH terms with an asterisk. The detailed search strategy is given in [Annexure 1]. The search strategy was kept broad to increase the sensitivity. In addition, we screened the reference lists of included studies and other reviews to identify any further eligible studies and searched the first 20 pages of Google Scholar. We reached out to four experts to identify any additional studies, and we received responses from two experts. These experts, who hold teaching positions in a renowned medical college and have worked in the field of palliative care within the department of community medicine, provided valuable experience and insights.

Data extraction and data managementA Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet was used to create a final data extraction table for analysis. The table included information such as the author’s name, the study location, the year of publication, the study design, and the number of people requiring palliative care, with a particular emphasis on capturing the proportion of individuals requiring palliative care. Data were independently entered in the data extraction form and were looked for discrepancies. We tried contacting the authors for the incomplete data. To manage the citations and remove duplicates we utilised Mendeley Desktop V1.19.5 software. To independently screen the articles we used the Rayyan application.[9]

Quality assessmentThe two independent authors (AC and AD) evaluated the risk of bias using the quality assessment tools recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies. This tool consists of nine questions designed to evaluate various aspects of the study. Based on the number of ‘yes’ responses to these questions, we categorised the studies into different quality levels. Studies were classified as ‘poor’ quality if the number of ‘yes’ responses was less than five, while studies with a number of ‘fair’ responses between 5 and 6 were classified as ‘moderate’ quality. Studies with more than seven ‘good’ responses were considered as ‘high quality’.

Data analysisThe Chi-square-based Q statistic test and I2 test were employed to assess the heterogeneity between the studies, with two-sided P-values. We reported the prevalence of the need for palliative care with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We have used the Freeman–Tukey transformation to adjust for the distribution of the studies. This prevalence was presented as the need for palliative care per 1000 individuals, we used the random effects model based on the DerSimonian and Laird method. To mitigate the risk of bias, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies of poor quality. To assess the source of heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the study site (Northern part of India vs. Southern part of India), the urban-rural distribution of the study site, gender and age group (<15 years, >15 years and >60 years) of participants with the test of interaction. To assess publication bias, we employed a funnel plot and used the Egger test to evaluate small study effects, with a P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA® software (version 18, STATA Corp).

ReportingThe entire process of literature search, screening, data extraction, systematic review, and meta-analysis was reported using the preferred reporting standard of systematic reviews and meta-analysis flow-chart and meta-analyses of observational studies in the epidemiology checklist to ensure scientific rigour [Annexure 2].

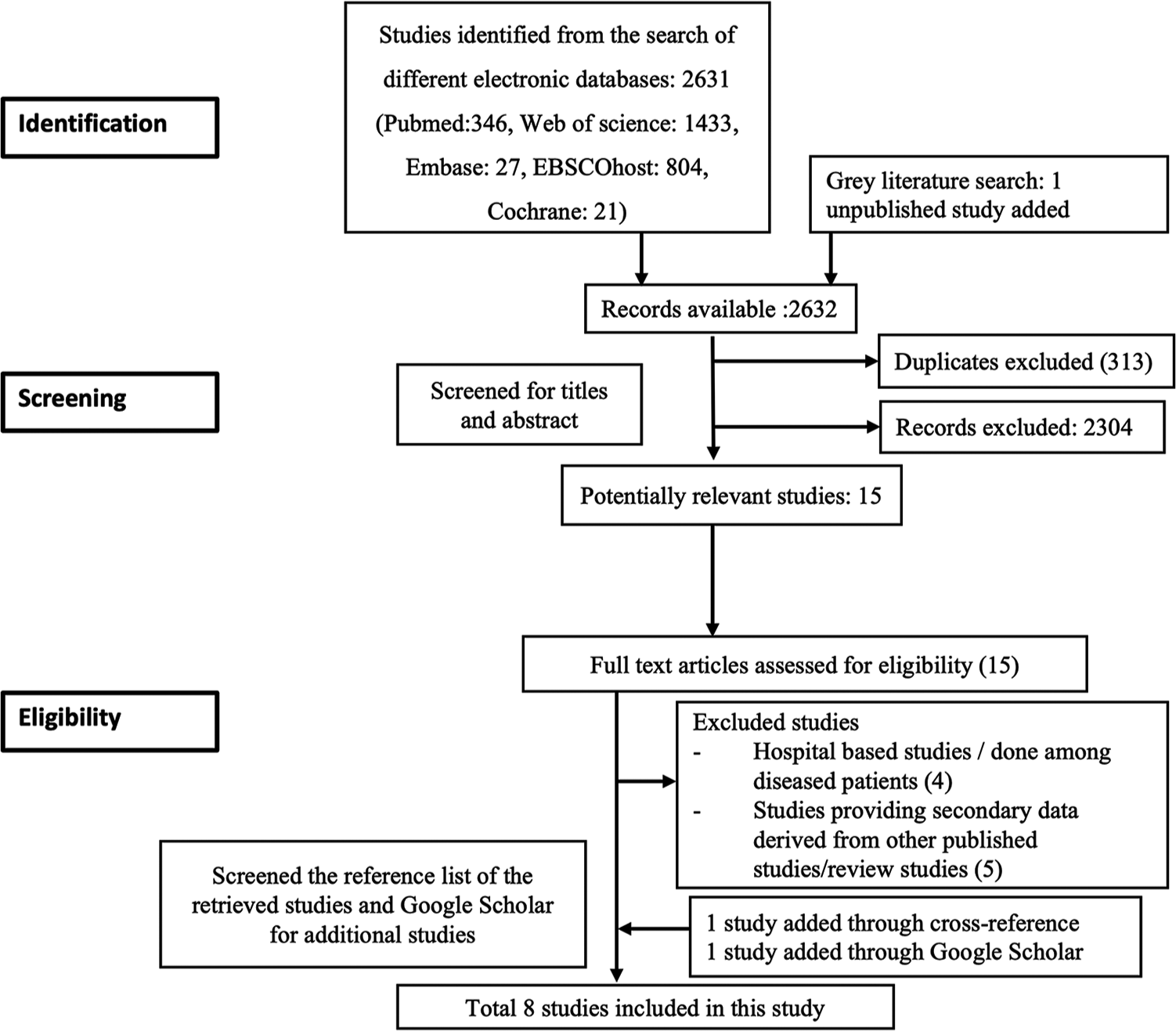

RESULTS Selection of studiesA total of 2632 articles were found in the search. We removed 313 duplicates and screened the remaining 2319 articles for title and abstract. After screening the title and abstract, 2301 articles were deemed ineligible and were excluded. Following the application of eligibility criteria, out of the full text of 15 articles, 9 studies were excluded [ Annexure 3]. Additionally, one study was incorporated through cross-referencing, and another was discovered via Google Scholar. Finally, a total of eight studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis [Figure 1].

Export to PPT

Description and quality of the studiesThe included studies in this analysis were conducted between 2016 and 2023, employing a cross-sectional research design. In terms of geographical distribution, three were conducted in North India, while the remaining were done in South India. Among the selected studies, five studies were conducted in rural settings, while the other three studies were carried out in urban areas. The majority of the included studies used a 3-item questionnaire to screen for the need for palliative care [Table 1]. One study used a supportive and palliative care indicator tool which has indicators,[8] while another study did not provide details about the methodology.[10] The sample sizes across the studies varied, ranging from 601 to 16,238 individuals. The estimated need for palliative care ranged from 1.5/1,000 population to 43.1/1,000 population. The quality assessment of the studies included in this analysis, of which six were rated as good quality and one study as fair quality [Annexure 4]. One study was found to be of poor quality,[10] which was excluded from the analysis.

Table 1: Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

S. No. Author Year of publication Place Location Setting Tool used for identifying the palliative need Households screened Sample size (individuals) Prevalence of palliative care 1. Chandra et al.[11] 2016 Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu South India Rural 3 item structured questionnaire 145 601 3.3/1000 2. Daya et al.[12] 2017 Puducherry South India Urban 3 item structured questionnaire 1,004 3,554 6.1/1000 3. Elayaperumal et al.[13] 2018 Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu South India Rural 3 item structured questionnaire 1,518 7,493 4.5/1000 4. Kaur et al.[22] 2020 Chandigarh North India Rural 3 item structured questionnaire 884 10,021 2/1000 5. Sudhakaran et al.[8] 2021 Karnataka South India Rural SPICT tool 522 2041 43.1/1000 6. Chandra et al.[7] 2022 New Delhi North India Urban 3 item structured questionnaire 2028 16,238 1.5/1000 7. Gowda et al.[10] 2022 Bengaluru, Karnataka South India Urban Not information available 741 2557 10.5/1000 8. Chandra et al.[14] 2023 Haryana North India Rural 3 item structured questionnaire 1831 9727 3.7/1000 Heterogeneity assessmentThe Cochrane q-test indicated heterogeneity (P < 0.01) with I2 = 97.38%. To account for this heterogeneity, a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was employed.

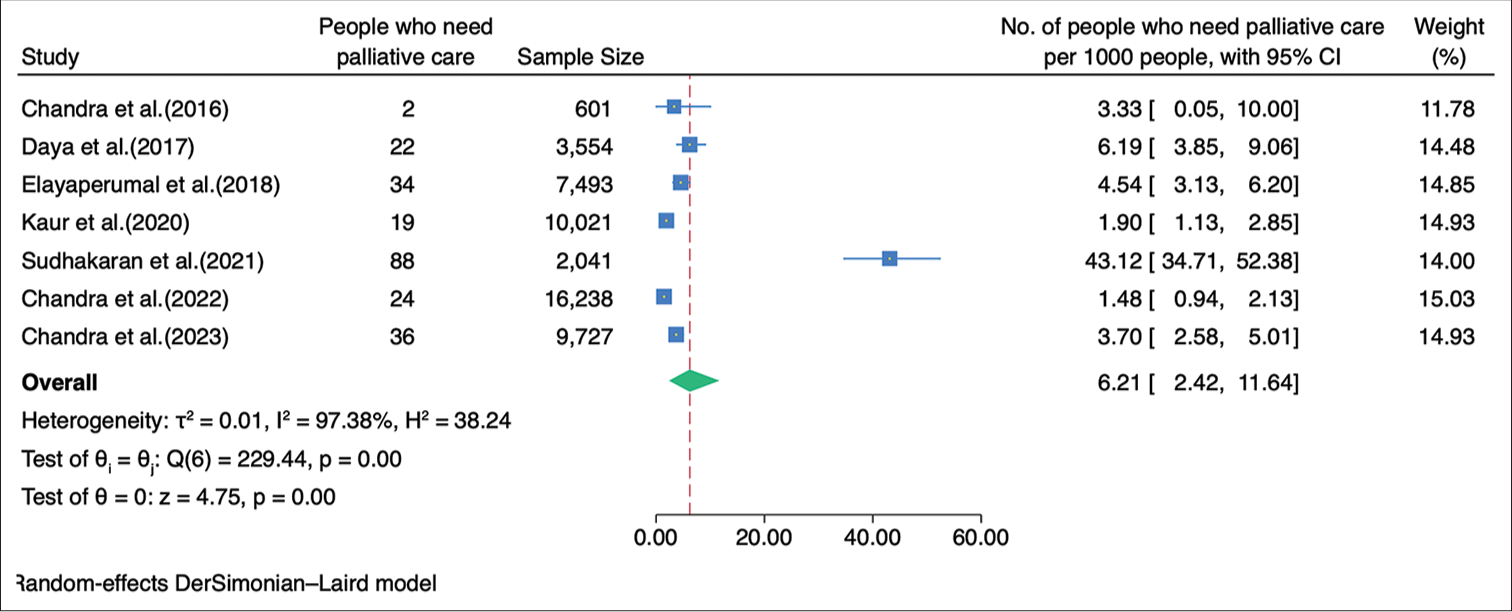

Need estimation in IndiaA meta-analysis was performed to determine the prevalence of palliative care, using data from 49,675 individuals in the included studies. Among these individuals, 225 were reported to require palliative care. The pooled estimate, obtained through the random-effects model, revealed a prevalence rate of 6.21/1,000 population (95% CI: 2.42–11.64) [Figure 2]. Five studies had provided detailed information regarding the specific diseases or conditions requiring palliative care.[7,11-14] In the details of 118 cases, with 53.4% of these cases being females. The spectrum of diseases encompassed both communicable and non-communicable conditions, as well as curable and non-curable illnesses. Among the identified cases, the most prevalent condition necessitating palliative care was a stroke, accounting for 26.3% of the cases, followed by old age-related weakness, which accounted for 22.9% of the cases and cancer (10.2%) [Annexure 5].

Export to PPT

Sensitivity analysisOn adding the excluded study in the analysis, the need of palliative care was found to be 6.69/1,000 population (2.93–11.90) [Annexure 6].

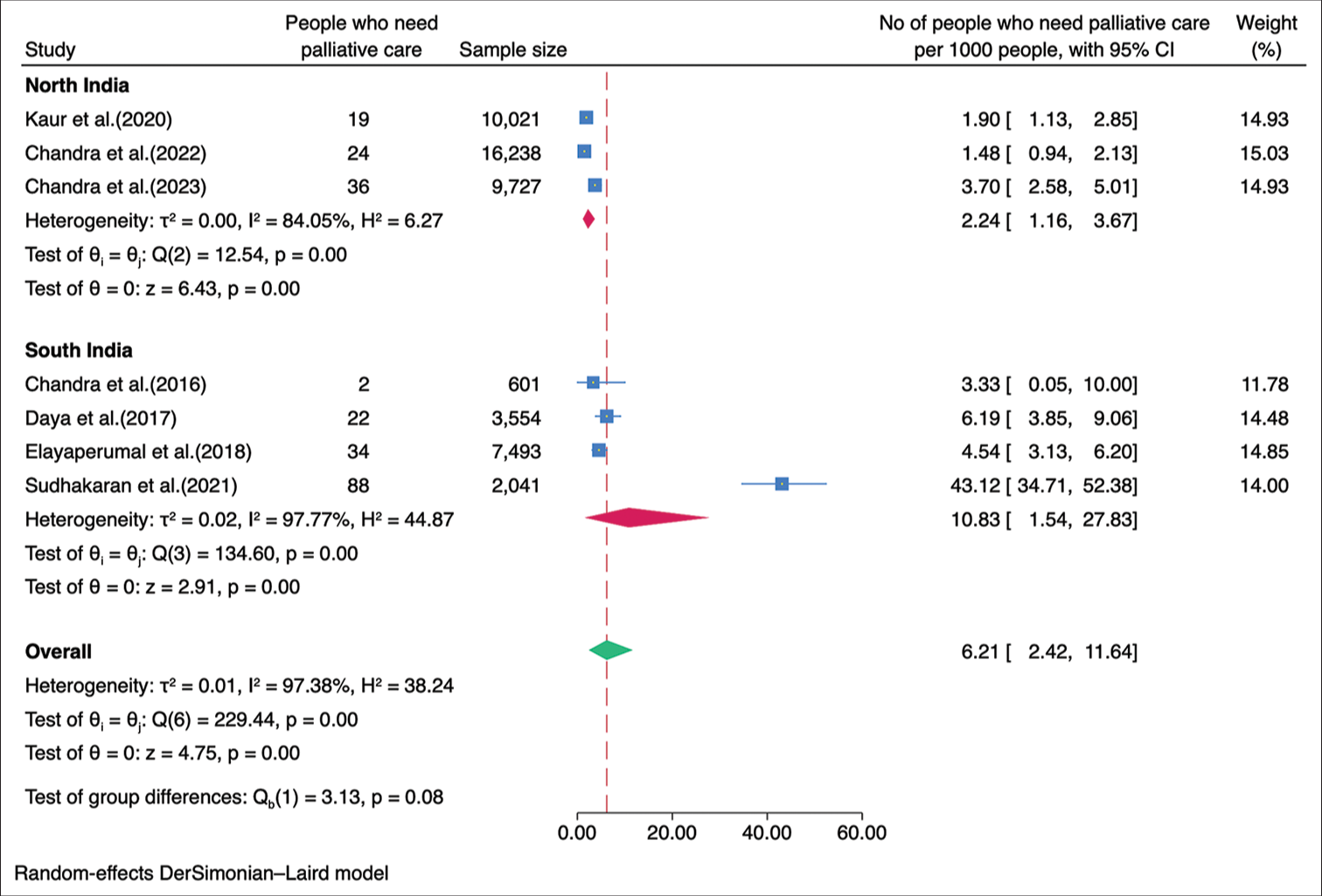

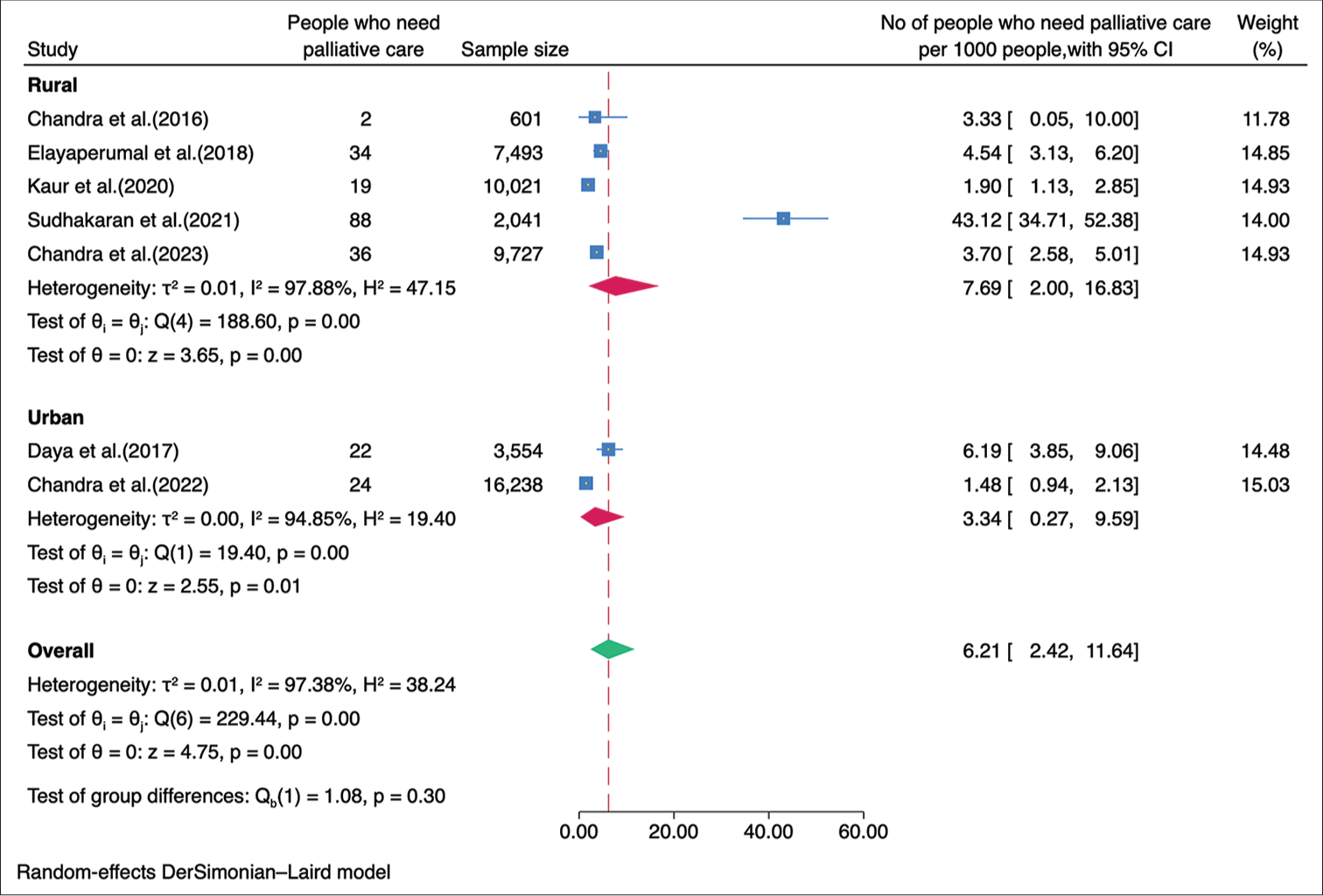

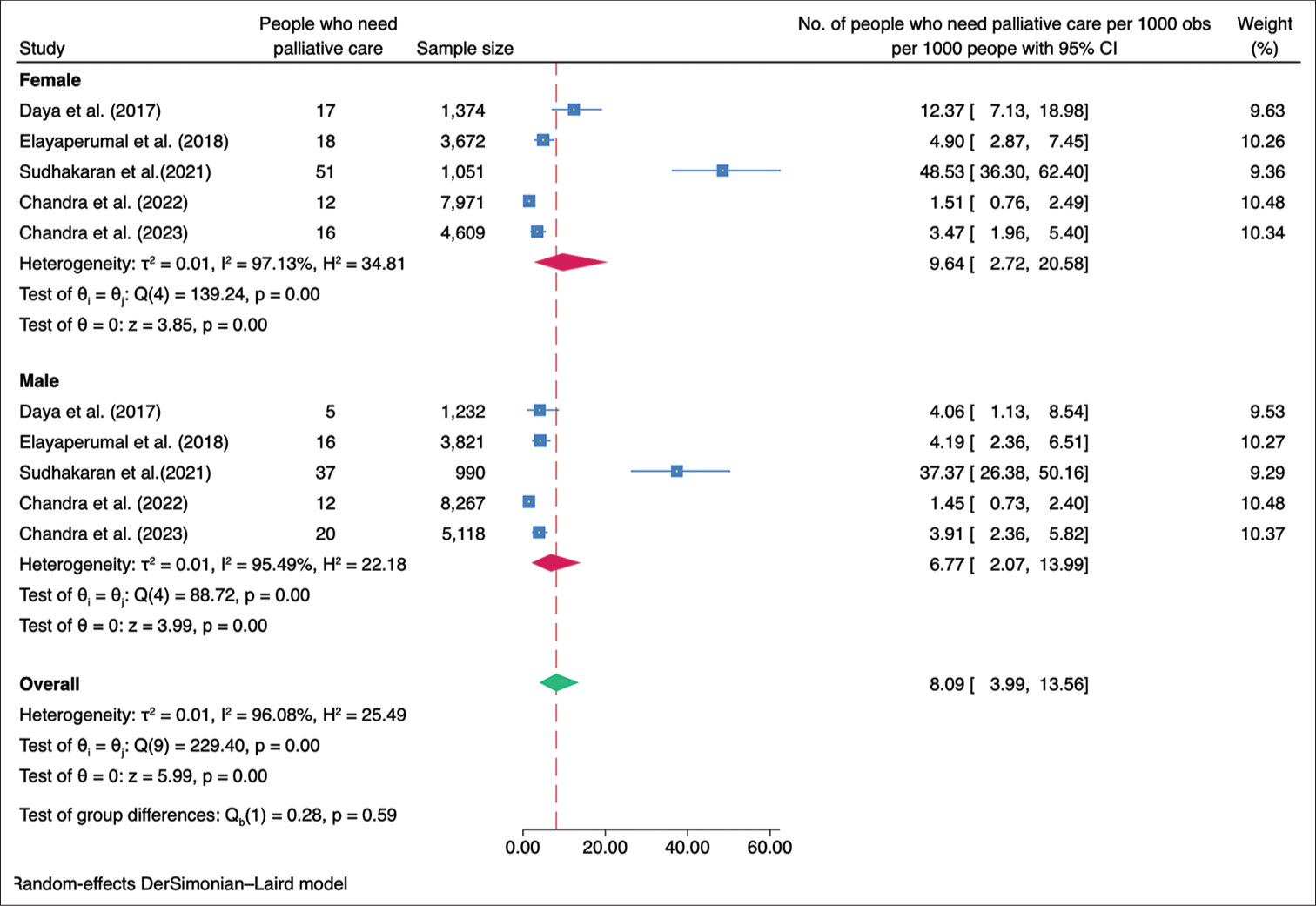

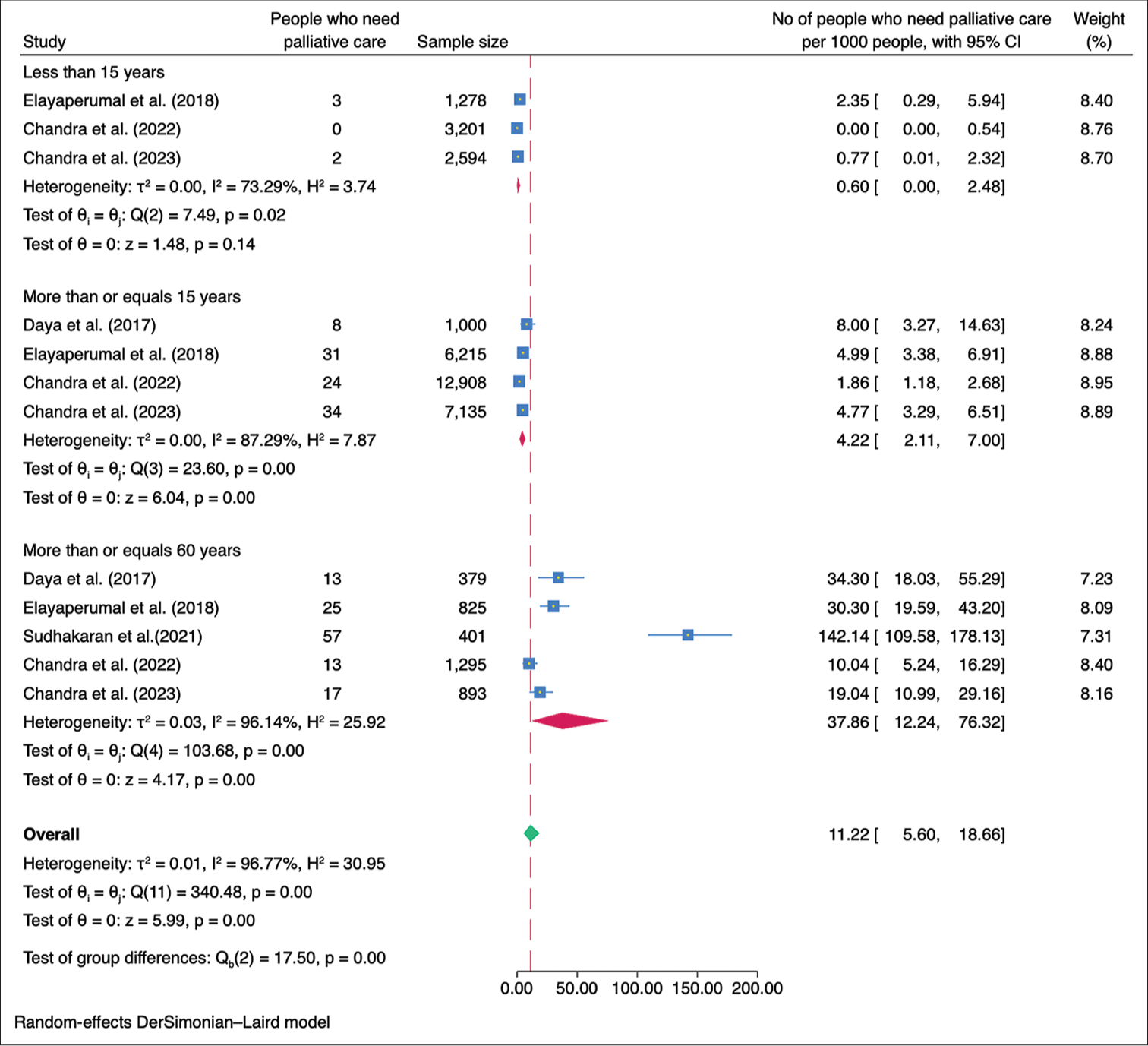

Subgroup analysisWe performed a subgroup analysis based on the geographical location of the studies. The studies were classified into those conducted in the northern and southern regions of India. The combined prevalence of palliative care needs among the studies conducted in the northern region was calculated to be 2.24/1,000 population (95% CI: 1.16–3.67), while the combined prevalence among the studies conducted in the southern region was found to be 10.83/1,000 population (95% CI: 1.54–27.83) [Figure 3]. The need for palliative care in rural areas was 7.69/1,000 population (95% CI 2.00–16.83) while in the urban areas was 3.34/1,000 population (95% CI 0.27–9.59) [Figure 4]. The need for palliative care among females was 9.64/1,000 population (95% CI 2.72–20.58) and among males was 6.77/1,000 population (95% CI 2.07–13.99) [Figure 5]. Moreover, the need for palliative care was found to be highest among participants aged over 60 years, as 37.86/1,000 population (95% CI 12.24–76.32). In contrast, those aged 15 years and more, had a need of 4.22/1,000 population (95% CI 2.11–7.00), while participants under 15 years had a lower need of 0.60/1,000 population (95% CI 0.00–2.48) for palliative care. There was a significant difference in the heterogeneity among the various age groups with I2 of 73.29%, 87.29%, and 96.14% (P < 0.001) [Figure 6].

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

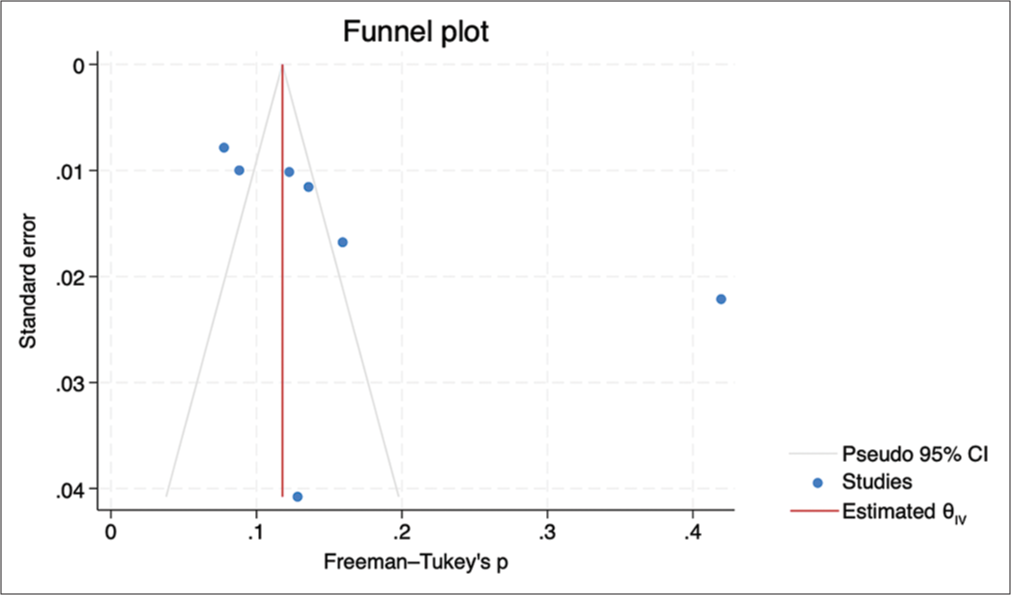

Publication biasThe funnel plot displayed a symmetrical distribution, and the Egger’s test revealed no evidence of small study effects (b = 3.04, P = 0.487) [Figure 7].

Export to PPT

DISCUSSIONThe estimated prevalence of palliative care needs in India (6.21/1,000 population) found in this meta-analysis was not affected by the sensitivity analysis. This estimate differs from the estimates reported in studies conducted in various countries.[15-19] These variations in prevalence may be attributed to different methodologies used in estimating the need for palliative care. Some studies rely on secondary data on mortality or disease prevalence, which may not fully capture the spectrum of palliative care needs.[20] In fact, the estimation of the global need for palliative care is primarily based on serious health-related suffering using mortality and prevalence data from the Global Burden of Disease Study. According to this estimation, the global need for palliative care is reported to be 56.8 million/year.[5] Considering a world population of 8 billion,[21] the estimated number of people requiring palliative care translates to 7.1/1,000 population. This estimate is quite similar to our study.

The source of heterogeneity could be due to the various tools used for screening and the difference in the age groups. Subgroup analyses unveiled disparities in palliative care needs concerning geographical location, differentiating between urban and rural areas, as well as gender and older age groups. Recognising the higher need for palliative care among specific populations, such as those residing in rural areas, females, and older adults, targeted interventions should be implemented to address their specific needs. This may involve improving access to palliative care services in rural communities, addressing gender-related barriers, and enhancing support for older adults with life-limiting conditions. Public and healthcare provider awareness regarding the importance and benefits of palliative care should be increased. Educational programs should be implemented to improve healthcare professionals’ knowledge and skills in palliative care, fostering a patient-centred and holistic approach to end-of-life care.

The strength of this study includes a comprehensive search across multiple databases and sources, including contacting experts, to identify relevant studies. We employed specific inclusion criteria, such as community-based studies in India involving the general population, which help ensure the relevance and applicability of the findings to the target population. The use of a standardised quality assessment tool strengthens the rigour of the study by evaluating the risk of bias in the included studies. Subgroup analyses were also conducted to explore variations based on important factors such as study site, urban-rural distribution, gender, and age groups. There were a few limitations of this study. The study only included articles published in English, which may introduce language bias and potentially exclude relevant studies published in other languages. Despite efforts to assess publication bias using a funnel plot and the Egger test, the potential for publication bias cannot be completely ruled out. The study identified high heterogeneity among the included studies. Although a random-effects model was used to account for this heterogeneity, it may still impact the robustness and generalisability of the findings. It is important to note that the geographic distribution of the included studies in this analysis was concentrated in North and South India, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other regions of the country. We were unable to report the need for palliative care at the household level due to a lack of data limits.

Future research in palliative care should prioritise key areas to enhance understanding and improve services in India. First, developing and validating standardised screening tools for accurately assessing palliative care needs in the general population is crucial. Reliable and comparable data across studies and settings will enable better identification and prioritisation of individuals requiring palliative care. Future studies should aim for diversity and representation by including samples from different regions of India. This will provide a comprehensive understanding of nationwide prevalence, enabling targeted interventions and resource allocation based on regional requirements. Longitudinal studies tracking changes in palliative care needs over time are necessary to identify evolving patterns and trends. Insights from such studies will help healthcare providers and policymakers adapt their strategies accordingly. Targeted interventions for specific population groups, including children, the elderly, and individuals with specific conditions, should be explored to effectively address their unique palliative care needs. Assessing patient outcomes and quality of life is essential to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of palliative care services. Longitudinal research can identify long-term benefits and challenges associated with interventions, while qualitative research provides deeper insights into patient and family experiences, guiding the development of patient-centred and culturally appropriate services. Regular evaluation and monitoring of palliative care programs are crucial for continuous improvement and quality assurance. This involves assessing accessibility, availability, and quality of services across different healthcare settings and regions. It will also help identify barriers and facilitators to effective implementation, informing evidence-based policy decisions and interventions.

CONCLUSIONThis study highlights the substantial need for palliative care in India. Subgroup analyses indicated a higher prevalence in the southern region, rural areas, among females, and individuals aged 60 years and older. The findings of this study will also provide guidance for healthcare providers and policymakers in the allocation of resources for palliative care services. Future research should focus on developing standardised screening tools, including diverse samples, conducting longitudinal studies, exploring targeted interventions and its outcome, and regularly evaluating and monitoring program implementation.

留言 (0)