The pain that cancer patients experience (cancer pain) is known as total pain[1] and can be acute, chronic, acute chronic, nociceptive, neuropathic, etc., or a combination of all of them. It occurs in up to 70% of patients[2] and is usually moderate to severe in intensity in 50% of patients who are in advanced stages of the disease.[3] Of the abdominal neoplasms, pain is more prevalent in patients with malignant tumours of the stomach and pancreas.[3,4]

The treatment of chronic cancer pain consists of the use of a multimodal therapy, based on pharmacology, taking into account the intensity of pain called the therapeutic ladder of the World Health Organization.[5] In this therapeutic algorithm, powerful opioid drugs play a fundamental role and interventional analgesia techniques are considered as the last step of treatment for chronic refractory pain.

In advanced neoplastic diseases, conventional therapies (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) often do not meet the objective of controlling it or have unacceptable side effects.[6] The continuous increase in the doses and the frequency of administration of opioids increases the risk of the appearance of side effects such as nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal problems, and itching, among others, causing a decrease in the quality of life of the patient.[7] In these cases, interventional analgesia techniques are required.

A viable option, for the treatment of chronic refractory pain in the upper half of the abdomen within the interventional field, is the inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system. There are different techniques such as celiac plexus neurolysis (CPN) (percutaneous, endoscopic, or surgical) or the neurolysis of the splanchnic nerves (NSN) (percutaneous or surgical). NSN is used mainly as an alternative to CPN when anatomical changes, adhesions, lymphadenopathy, tumour infiltration, etc., may reduce the effectiveness of the latter or when it fails.[8] The celiac or solar plexus is located in the retroperitoneum, on the anterolateral wall of the aorta at the level of the body of the first lumbar vertebra (L1). It provides sympathetic, parasympathetic and sensory innervation to multiple intra-abdominal structures: pancreas, liver, gallbladder and bile duct, spleen, adrenal glands, kidneys, stomach, the lower third of the oesophagus, duodenum, and part of the transverse colon.[9,10]

Percutaneous neurolysis of the celiac plexus consists of a minimally invasive procedure that can be performed using different imaging techniques (fluoroscopy, ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging). It consists of the injection of a neurolytic agent (ethanol or phenol), which generates a Wallerian degeneration of the plexus,[9,10] interrupting the sensory pathway to the central nervous system to relieve pain for a long time.[11] In CPN, the approach can be posterior (patient in the prone position) or anterior (patient in the supine position). In the posterior approach, a unilateral or bilateral transcrural technique (identifying the L1 vertebral body), transaortic (accessing the left side of the L1 vertebral body through the aorta) or transdiscal (crossing the T12–L1 intervertebral disc and reaching splanchnic nerves) can be used. The anterior, ultrasound-guided, or tomography-guided approach usually uses a single puncture. The volume of the neurolytic substance is variable: between 10 mL and 30 mL depending on whether phenol or alcohol is used and it is generally preceded by the administration of contrast (except in the ultrasound technique) and a local anaesthetic drug.[8]

On the other hand, endoscopic neurolysis has the advantage of allowing direct access to the celiac plexus from the antecrural plane through 180° ultrasound cuts, allowing the puncture to be performed in real-time; the patient must be in the left lateral decubitus and low conscious sedation controlled by an anaesthesiologist. In the case of bilateral puncture, 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine plus and 10 mL of 98% alcohol are administered to each side of the aorta. Since alcohol makes it difficult to recognise structures by ultrasound, it is preferable to perform a single puncture in the anterior part of the aorta in the endoscopic technique.[12] CPN is a well-tolerated technique that is performed under local anaesthesia. The most frequent side effects are mild and transitory and depend on the type of technique used, known as, pain in the puncture site, diarrhoea, and orthostatic hypotension.[7,8] The main benefit of CPN is the reduction in a variable degree of the intensity of pain, although the evidence in this regard is limited concerning its safety and efficacy.[13-15] However, there are, indeed, up-to-date primary studies on CPN, where CPN is generally analysed by comparing alcohol volumes[16] or comparing the use of a single or double needle.[17]

Since CPN is the analgesic technique of choice for the treatment of refractory chronic cancer pain due to advanced neoplasms of the upper hemiabdomen, it is relevant for these patients to analyse the level of evidence on the efficacy and safety of the CPN.[11,18,19]

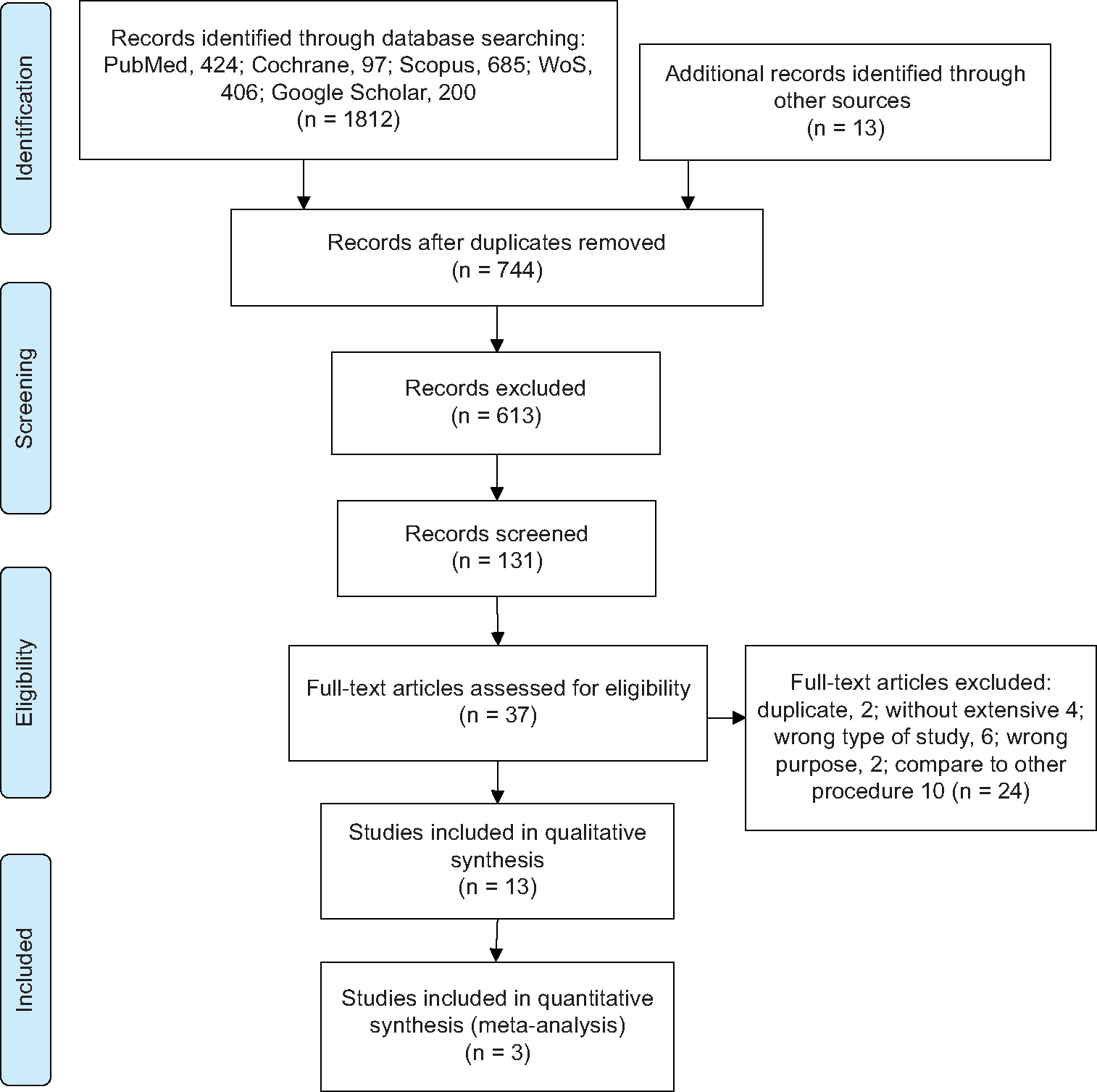

MATERIAL AND METHODSA systematic review was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA),[20] following the CRD42021241713 protocol registered in PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews), available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record. php?RecordID=241713.

We formulate the research question using the PICO methodology.[21] PATIENTS: Upper abdominal cancer with refractory chronic pain. INTERVENTION: CPN and COMPARATOR: Systemic pharmacological analgesic treatment. OUTCOME: Efficacy and safety.

Search strategyA bibliographic search was carried out in five electronic databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) between 1 January 2000 and 12 April 2021, including the following terms: Population: Cancer, neoplasms or abdominal pain and intervention: Neurolysis, nerve block or celiac plexus in English, Spanish and Portuguese. In addition, the list of bibliographic references was reviewed (snowball strategy) and a search was carried out in the grey literature [Annex 1].

Study selectionOne author searched all five databases by title and abstracts; then, duplicates were identified and removed using the Mendeley 1.19.4 reference manager. Three authors independently reviewed the selected full-text articles following the following criteria:

Inclusion criteriaRandomised and controlled clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of CPN (percutaneous or endoscopic ultrasound) in patients over 18 years of age with chronic pain due to upper abdominal cancer were included in the study.

Exclusion criteriaSystematic reviews and meta-analyses, studies compared with other procedures, surgical techniques, and radiofrequency neurolysis, studies that were not in full text, or those in which the methodology was not clearly specified were excluded from the study.

The doubts were resolved by consensus among the reviewers.

Data extractionFrom the studies finally included in the review, the data were extracted by two of the authors independently, using a pre-designed data extraction sheet to collect information on the author and year of publication, country of origin, type of study, patients, comparator, characteristics, measurement, technique, and conclusions.

Quality assessmentThe senior author assessed the quality of the data and the risk of bias in all the included studies, applying the Jadad scale modified by Oremus et al.,[22] which assigns a score from 0 to 5, considering the form of randomisation of patients, blinding and loss of individuals and excluding low-quality studies (score <3).

Synthesis of resultsIn studies with adequate quality and similar characteristics, global estimates were made in the pooled analysis using Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 5.3);[23] the weighted difference of means (with 95% confidence interval) of the selected studies based on a random effects model, a variant of the inverse of the variance method that incorporates intra- and inter-study variability. The heterogeneity of the estimates was assessed using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation, not the sampling error between studies. An I2 value >75% indicates high heterogeneity.

RESULTS Selected studiesA total of 744 publications were identified according to the search criteria, 13 of them were selected for qualitative synthesis, three of which met criteria for quantitative synthesis and efficacy of the procedure. Figure 1 shows the sequence that the selection of articles follows. The researchers in charge of the selection of articles had a good inter-rater agreement (Cohen’s Kappa Index 0.61). Seven studies compared the efficacy and safety of CPN with conventional pharmacological treatment except for Gao et al.’s,[24] who did not evaluate the safety of the intervention [Table 1]. Six studies compared the efficacy and safety of technical variations of the same procedure (access, imaging technique used, number of punctures, or substance used) except the case of Ugur et al.,[25] who did not assess safety [Table 2]. Thus, of the 13 studies selected, only 10 met the criteria for the analysis of the safety of the technique [Table 3].

Export to PPT

Table 1: Characteristics of controlled clinical trials that compare CPB with conventional pharmacological treatment.

AUTHOR COMPARE PATIENTS MESUREMENT TECHNIQUE CONCLUSION WongTable 2: Characteristics of controlled clinical trials that compare technical variations of the same procedure.

AUTHOR COMPARE PATIENTS MESUREMENT TECHNIQUE CONCLUSION Ugur et al. 2007 (Turkey) PER-CPB with two needles vs one needle with 2 stylets Pain due to Pca Number of punctures and fluoroscopy injection time L1 Posterior access, F-guide, 21G needle, Bu 0.5% 15 ml, OH 50% 10 ml The use of a single needle may be a more effective and appropriate method for beginners or practitioners of other specialties. LeBlancTable 3: Adverse effects associated with celiac plexus neurolysis.

AUTHOR Procedure Technique n Patients % adverse effects Transient hypotension Local pain Transient diarrhea Lightheadedness or dizziness Nausea or vomiting Others adverse effects JainFour studies concluded that the decrease in pain was significantly greater in the group that received celiac neurolysis compared to the group that only used conventional pharmacological treatment.[24,26-30] The other three studies report that they found no significant difference in relation to this variable.[31-33]

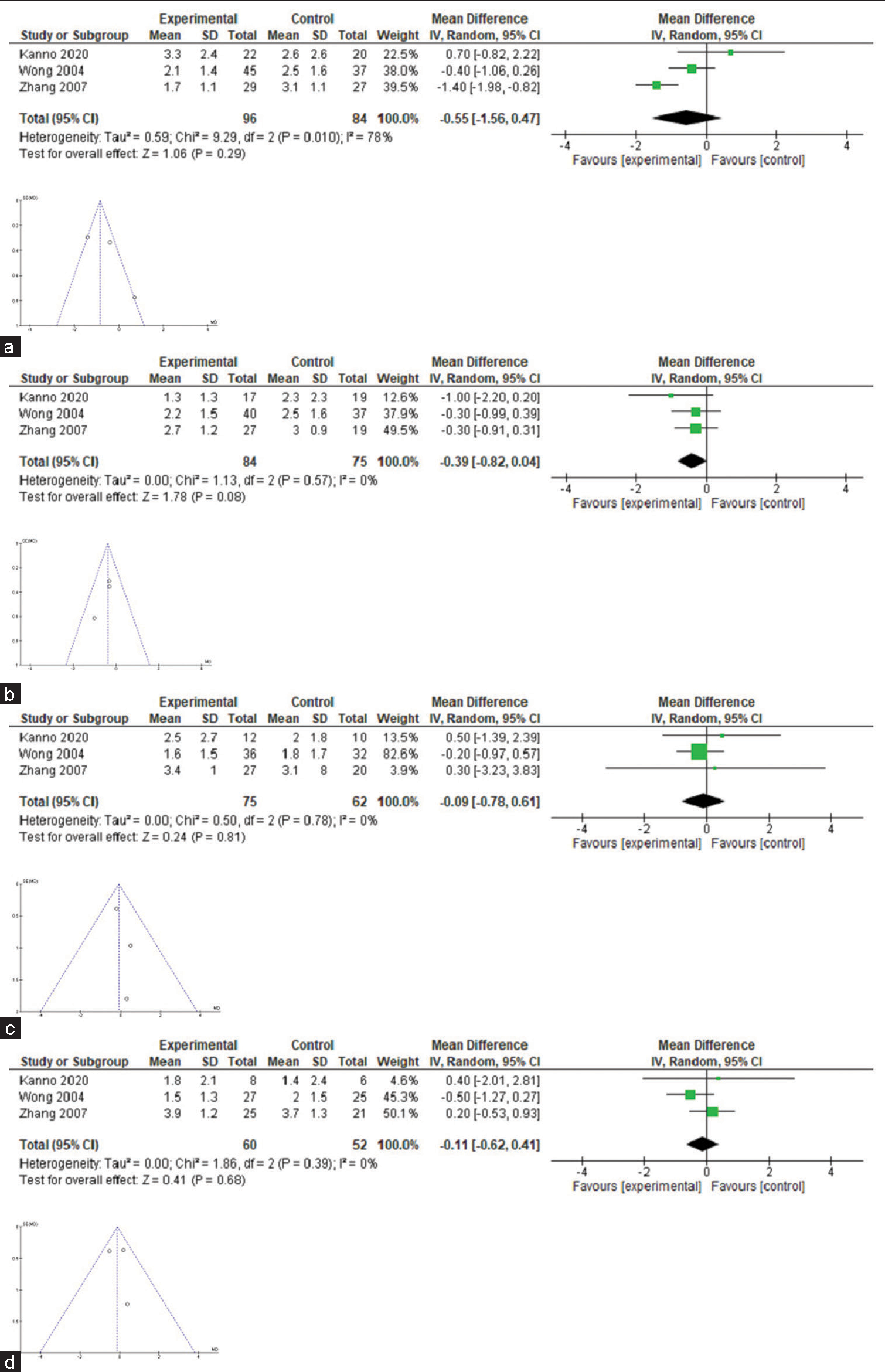

Only three trials[24,30,33] fulfilled the conditions for the estimation of meta-analysis in relation to pain intensity with celiac neurolysis versus conventional pharmacological therapy [Table 4]. The difference in pain intensity means was −0.55, −0.39, 0.16, and −0.11 in weeks 1, 4, 8, and 12 after the procedure, but no confidence interval excluded zero [Figure 2]; heterogeneity was high (I2 78%) in week 1 comparisons, but 0% in all other comparisons. Of these three, only one shows a significant difference in the 1st week.

Table 4: Quality of the trials (Jadad scale).

Trial Describe Is adequate Punctuation Randomized Double blind Dropouts exclusions Randomization Blinding Wong et al. 2004 1 1 1 1 1 5 Jain et al. 2005 0 0 1 -1 -1 -1 Zhang et al. 2007 1 1 1 1 -1 3 Wyse et al. 2011 1 1 1 -1 -1 2 Amr et al. 2013 1 0 0 1 -1 1 Gao et al. 2014 1 1 0 1 -1 2 Kanno et al. 2020 1 1 1 1 -1 3

Export to PPT

Reduction of opioid consumptionThree trials reported a significant decrease in opioid consumption in the group that received neurolysis compared to the control group[26,28,29,34] and one trial concluded that there was no difference in opioid consumption in the groups evaluated.[30] It was not possible to perform a quantitative synthesis of opioid use due to a lack of uniformity in the communication of the results.

Reduction of pain intensity comparing technical variations of the same procedureThree studies compared the use of one versus two needles during CPN, different approaches, and imaging techniques. One of them concluded that using a needle had a lower failure rate and shorter procedure time compared to a double needle, but its safety was similar since there were no significant differences in the use of rescue analgesia and the presence of complications.[17] Furthermore, the other two did not find significant differences in pain relief or safety of the procedure,[23,25] mentioning it could be more appropriate for poorly trained personnel.

The use of 40 mL of 70% alcohol was more effective than 20 or 30 mL in percutaneous neurolysis in gallbladder cancer.[35] The third study concluded that using 15 mL of 50% alcohol had similar pain control as 100% alcohol in percutaneous neurolysis due to pancreatic cancer, but the latter presented greater complications.[17]

Technique-related adverse events in CPN.

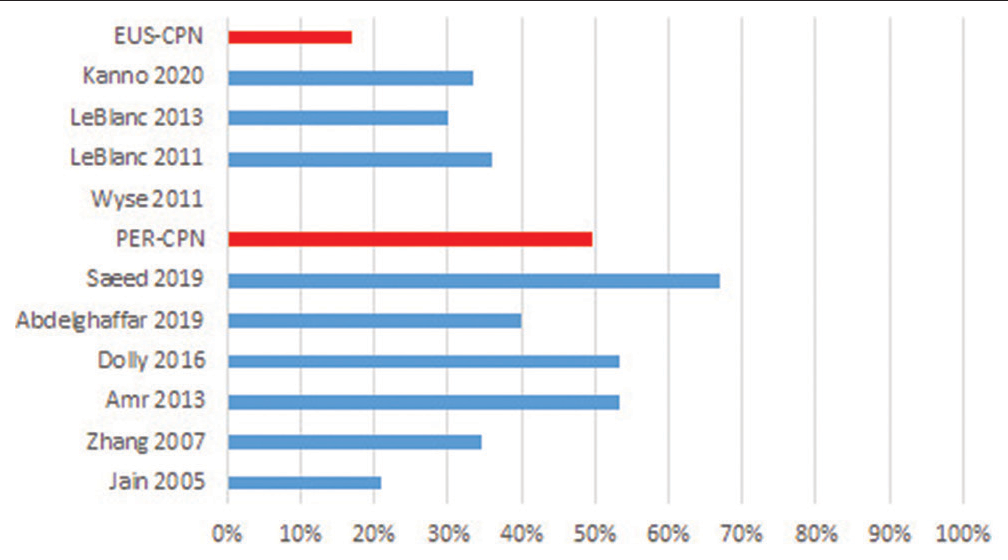

In ten of the identified studies, transient (hours or a few days) and mild adverse effects related to CPN were reported (between 21% and 67%), mentioning orthostatic hypotension, dizziness/light-headedness, diarrhoea and pain in the puncture site; identifying that in the studies where neurolysis was applied percutaneously, they reported a greater number of adverse events compared to the endoscopic route: 49% versus 17%, respectively. In the study by Saeed et al.[26] for the percutaneous technique, 67% of complications were found, while the one of LeBlanc et al.,[35] 36% were observed for the endoscopic technique [Figure 3].

Export to PPT

Quality of lifeSix out of seven clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy and safety of CPN, compared to conventional analgesic treatment, analyse the quality of life and/or functionality of patients with the treatment. Three trials reported better quality of life or functional status of patients in the group that received neurolysis;[8,29,34] however, another three concluded that there were no significant differences between the groups[24,27,33] and one of them did not analyse this variable.[30] Numerical estimates could not be made because the studies used different ways of estimating the quality of life variable and in other cases due to the significant loss of patients to follow-up.

DISCUSSIONThe goal of this study is to carry out an evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of CPN for the treatment of persistent chronic cancer pain caused by upper abdominal neoplasms in comparison with pharmacological analgesic treatment through a systematic review of the literature.

A total of 13 controlled clinical trials have been identified, a greater number than in the previous reviews,[11,18,19,36] comparing both technical variations of the procedure and conventional analgesic treatment in a highly variable number of patients, with heterogeneity being the rule. Only three clinical trials met the criteria for quantitative analysis,[24,30,33] because they analysed patients with pancreatic cancer, comparing various neurolysis techniques (endoscopy-guided[33] or computed tomography[30]) with analgesic treatment and monitoring the patients weekly to identify the intensity of pain and the need for opioid consumption, additionally, they analysed the variation in the quality of life after neurolysis. The most studied pathology of all upper hemiabdomen neoplasms among the selected articles was pancreatic cancer (eight studies). An increase in the number of studies with procedures guided by endoscopic ultrasound versus the percutaneous technique has been observed in recent years.

This review shows that CPN is performed using a wide variety of techniques, with the same objective of controlling pain in cancer patients, which, when compared with conventional treatment, provides a reduction in pain intensity higher in the first weeks of treatment with a decrease in opioid consumption and being satisfactory for the patient because it indirectly improves their quality of life with the presence of adverse effects that are, in general, transitory and manageable. If we focus exclusively to the three studies that met the criteria for quantitative synthesis,[24,30,33] we can say that with this level of evidence, there is no significant decrease in the intensity of pain due to upper hemiabdomen cancer in weeks 1, 4, 8 or 12 with the application of celiac neurolysis compared to conventional drug treatment.

However, when evaluating the included controlled clinical trials, we can observe that the intensity of pain in the follow-up of patients is significantly reduced at the beginning in both therapies, but less in subsequent weeks. In a single study, it was possible to identify continuity in the degree of decrease in pain intensity for those who received neurolysis, turning out to be significant,[24] while in the other studies, there were no significant differences with respect to patients receiving conventional pharmacological analgesic treatment.[33] In this sense, regarding the variation in pain intensity in upper abdominal cancer, several clinical trials report a significant decrease in pain in the group that received neurolysis[26,27,29-31] while others showed no variation,[31,33] but few studies met the criteria for quantitative synthesis that did not show a significant difference.

This differs from that reported by Nagels et al.,[18] who of 66 selected studies included five studies for quantitative synthesis and found a decrease in pain in the intervention group during the first 2 weeks. At the same time, in the review by Yan and Myers,[19] when analysing five randomised clinical trials, they found a significant decrease in the second, 4th, and 8th weeks after the procedure. Instead, different results were found by Nobre et al.,[37] who found no significant differences in pain relief in the 1st week after the procedure in the study group, while at 12 weeks, they were mainly observable in patients who received endoscopic ultrasound-guided CPN.

This discrepancy in the results obtained by the different studies and the absence of significant difference in the efficacy of pain control in CPN compared to conventional pharmacological treatment may be due to the rotation or combination of different drugs in the context of a strategy flexible multimodality to adapt to the changing needs of the patient,[38] but we could also attribute variable criteria for the selection of patients that could make these not representative of the type of advanced cancer patients with refractory pain to whom the technique is offered in the context of palliative care.[8] Last but not least, significant pain relief is more feasible in patients with pain intensity >7 according to the visual analogue scale than in patients with moderate pain intensity, frequently finding both types of pain. Both types of patients were included in the same study.[8]

Collaterally, since it is not a primary objective of the review, we present four studies that found a reduction in opioid consumption in patients with upper abdominal cancer pain who received celiac neurolysis, compared to conventional analgesic therapy,[26,28,29,34] being like that reported by Nagels et al.[18] and Yan and Myers.[19] These results could not be quantitatively evaluated due to methodological differences between them, such as the presence of patients with and without refractory pain, or the measurement of the variable, either qualitatively (presence and/or absence of consumption of these drugs), or quantitative (amount of your consumption). Although these results are not verifiable, they offer an indirect measure of the efficacy of celiac plexus block (CPB) compared to conventional analgesic therapy as an opioid-sparing strategy in patients with advanced refractory chronic cancer pain.

In the section on adverse effects related to the neurolytic technique, its incidence is variable in the ten selected studies, between 21% and 67%. The main adverse effects were orthostatic hypotension, diarrhea, and pain at the puncture site in patients who received interventional treatment; and nausea, vomiting, and dizziness in those who received pharmacological treatment. Although in the aforementioned clinical trials, the population was homogeneous, the number of patients is small and the method of detecting these effects in each of the studies was not uniform, so it is not possible to do a quantitative analysis that allows us to offer conclusive results. It is interesting to note, for example, that the study by Wyse et al.[8] only collects the adverse effects and complications that prolong hospitalisation but did not register any event itself. However, if we compare the overall incidence of adverse effects separately in the studies that use both techniques, the difference in the appearance of adverse effects is evident, being higher when a percutaneous technique is performed, as shown in [Figure 3].

Analysing each study, it has been possible to identify that most of them use alcohol in different concentrations as the main neurolytic agent. When stratifying them according to the technique used, it is observed that, when percutaneous neurolysis is performed, using alcohol concentrations at 50%[29] has a lower frequency of adverse events than concentrations between 70% and 100%.[11,17,26,31,36] In contrast, with endoscopy-guided neurolysis, the use of 100% alcohol generates complications that prolong hospitalisation time,[28] while concentrations between 98% and 99% present transitory and rapidly resolving events.[16,17,35]

Adverse effects are non-serious and transitory, except in the study by Abdelghaffar et al.,[

留言 (0)