Muslims are frequent targets of negative stereotypes and discrimination, especially after the 9/11 attacks and the rhetoric of the 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign. This study examined how 129 American Muslim couples cope with perceived religion-based discrimination. Results indicate that perceiving that one’s religion is accepted by the community is negatively related to discrimination, and overt markers of Islam for men (clothing/grooming styles) is positively related to discrimination. Further, discrimination is linked with negative interactions between couples, which in turn is linked to lower relationship satisfaction. In other words, discrimination has an indirect effect on satisfaction through negative couple interactions. This indirect effect can be buffered by couples’ joint coping skills only when these skills are sufficiently developed.

Keywords: religion-based discrimination, Muslim couples, religious congruity, relationship satisfaction

As a minority group in the United States, Muslims face challenges related to identity, acculturation, and discrimination (Ahmed et al., 2011). Estimates vary as to the total, with a median estimate range of 3.45 million or 1.1 percent of the population (Lipka, 2017). The media’s portrayal of Muslims as terrorists after the September 11, 2001 attacks (popularly referred to as 9/11) is often cited for increased social disapproval and bullying; implicit discrimination increased by 82.6 percent and overt discrimination increased by 76.3 percent following the event of 9/11 (Sheridan, 2006). Although these rates tapered off over time, they have since intensified due to heated rhetoric by the current presidential administration, including a call to ban new Muslim immigration to the United States (Sullivan & Zezima, 2016).

While there have been many studies examining the direct effects of Islamophobia and discrimination on the mental health of American Muslims, there have been few studies of discrimination’s effects on Muslim couples. Discrimination, including perceived religious-based discrimination (PRBD), is positively related to stress (Abu-Ras et al., 2018), negatively impacts mental and physical health (e.g., Schmitt et al., 2014), and adversely affect relationship outcomes for interracial couples (e.g., Baptist et al., 2018). However, research has also shown that such couples are able to mitigate against negative effects of discrimination and protect relationships. Positivity, openness, dyadic coping skills, and the strength of one’s religious faith have been found to attenuate the effects of perceived discrimination and strengthen relationships (e.g., Baptist et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2014). Muslim couples may have similar strategies that help buffer the effects of PRBD. This study examined the how Muslim couples cope with PRBD and how these experiences affect their relationships. Findings could better prepare clinicians to work with Muslim couples.

Discrimination of Muslims in the United StatesMuslims first immigrated to North America 400 years ago. Today, the Muslim population in the United States comprise African Americans and descendants of immigrants from the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, Asia Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa (Lipka, 2017). The rise of fear and persecution have displaced and forced many Muslims to flee their homeland. Several countries including the United States have helped resettle Muslim refugees who are not always welcomed by local residents who may associate Muslims with terrorism (DeSilver, 2015). The Federal Bureau of Investigation reported that anti-Muslim hate crimes have seen a steady increased from 154 in 2014 to 307 in 2016 (Kiski, 2017). The overt markers of Islam can exacerbate the likelihood of being targets for discrimination. Muslims who adorn traditional clothing (e.g., hijab for women) or maintain traditional grooming styles (e.g., long beard for men) are more easily identified and targeted for hate crimes (Fozdar, 2011). Muslim women who wear headscarves experience more discrimination than Muslim men and Muslim women who don’t headscarves (Jasperse et al., 2012; Rahmath et al., 2016).

Effects of DiscriminationThe race-based traumatic stress theory (RBTST; Carter, 2007) describes how discrimination on minority populations can inflict harm. Discrimination can elicit reactions and/or symptoms that represent depression, avoidance, vigilance, and isolation (Carter, 2007), physical illness (e.g., heart disease, high blood pressure, cognitive impairments, poor sleep, and visceral fat; Paradies et al., 2015) and if not addressed or managed well can culminate to being a traumatic experience. Untreated trauma can in turn increase vulnerability and threaten romantic relationships.

Although RBTST was not developed with religion-based discrimination in mind, the effects of religion-based discrimination are similar to the effects of race-based discrimination. For instance, a review of literature by Samari and colleagues (2018) found that discrimination against Muslims or Islamophobia was linked to poor mental health and poor health-seeking behaviors and health outcomes. A report on Islamophobia in the United Kingdom (Elahi & Khan, 2017) documents not only its growth over the previous 20 years, but the cumulative effects on Muslims. Accordingly, discrimination increases exposure to internalized destructive messages that can lead to reduced self-esteem and mental health (Jones, 2000) and physiological changes that can worsen physical health (Clark et al., 1999). Violence resulting from acts of discrimination directly affects mental and physical health. In fact, psychosis was found to be five times more prevalent and depression three times more prevalent in ethnic minorities who reported physical attacks as a result of discrimination than those who reported no harassment (Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002). The impact of discrimination whether based on race or religion has the potential to harm the overall wellbeing of its victims and exert stress onto their relationships.

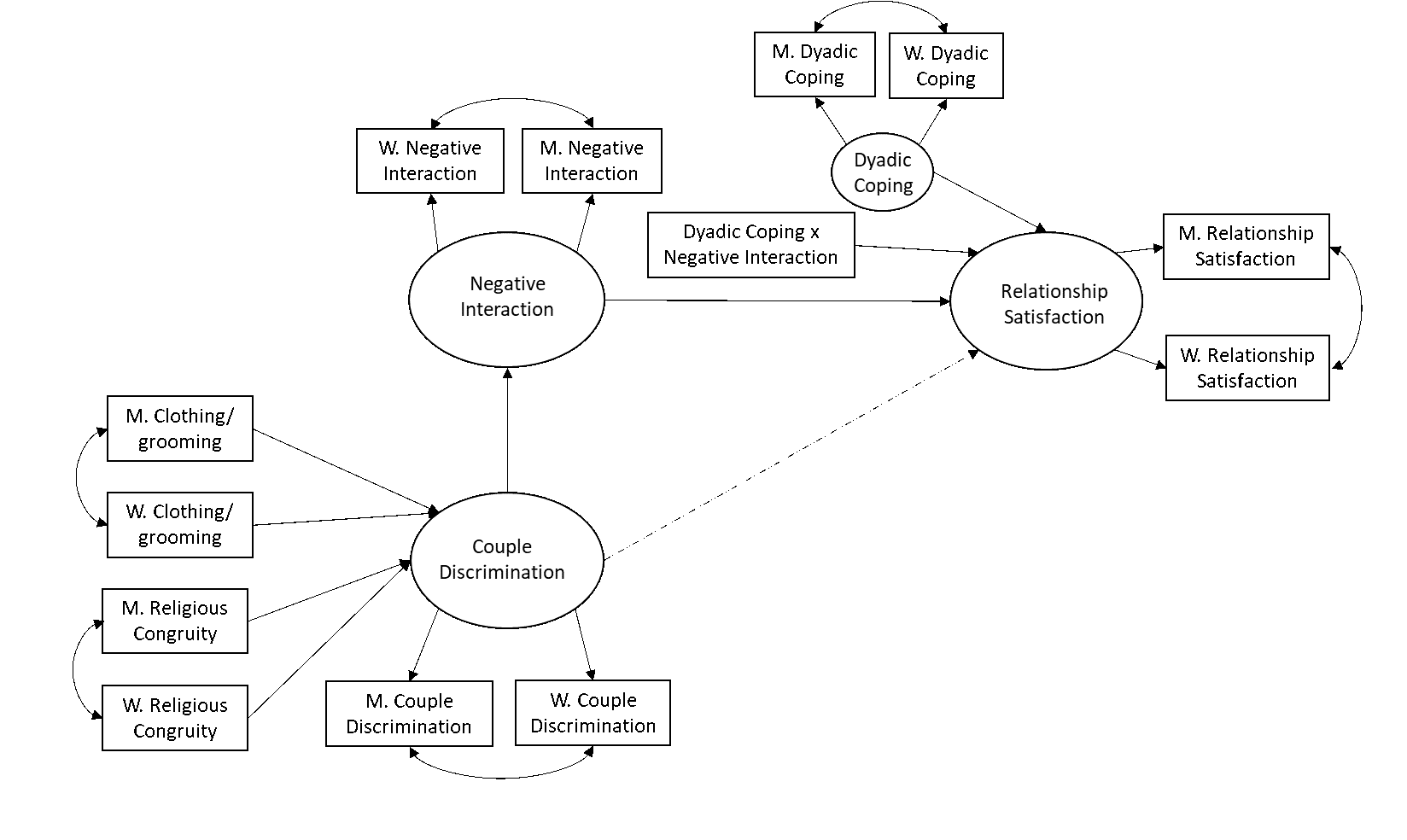

Healthy relationship processes and individual strengths can provide couples with strategies to counter the effects of discrimination. The stress process model (SPM; Pearlin et al., 1981) suggests that the ability to manage social stress (i.e., adverse life events and chronic or ongoing strains) is dependent on the meaning ascribed to the stress and on the capacity to access social and personal resources (Pearlin et al., 1981). These resources can help explain why people experience different outcomes when they encounter similar stressors. These frameworks were used for the proposed model (Figure 1), where PRBD was modeled as a social stress, negative interaction and dyadic coping were modeled as mediator and moderator, respectively, and relationship satisfaction served as the stress outcome.

Figure 1. Common-fate moderated mediation model of perceived religion-based couple discrimination on relationship satisfaction.Note: W = Women. M = Men. Path with dotted line was omitted in the final model.Discrimination and Relationships

Figure 1. Common-fate moderated mediation model of perceived religion-based couple discrimination on relationship satisfaction.Note: W = Women. M = Men. Path with dotted line was omitted in the final model.Discrimination and RelationshipsStudies revealed that same-sex and interracial couples experience negative reactions and public disapproval such as stares, jokes, comments, housing discrimination, and restricted travel and leisure opportunities due to safety issues (Bell & Hastings, 2011). These forms of stressors can create tension and destructive communication or negative interaction between couples that may result in conflict, hostility, poor problem-solving, demand–withdraw patterns of communication (Papp et al., 2009), and avoidance or invalidation of partners’ feelings and concerns (Fekete et al., 2007). Negative interactions between couples are associated with lower levels of satisfaction and higher rates of marital stress (Markman et al., 2010). While the conflict within relationships that stem from stress can have a negative effect on satisfaction, the challenges of discrimination can strengthen relationships by creating opportunities for closeness and support (Baptist et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2014). Although the effects of discrimination on U.S. Muslims has been well-researched, research on the effects of discrimination on couples’ relationships is scarce. A recent study with six Muslim couples described how shared faith practice helped couples cope with religious discrimination following 9/11 (Carter, 2010). This study examined two resources: religious congruity and dyadic coping.

Religious CongruityIn this study, the concept of congruity refers to fitting in with society and feeling accepted. Literature on congruity refer to the sense of belonging to a society and the fit between one’s cultural values and those of society (Chaves, 2010). Studies have found that minority students’ cultural congruity with their university environment was related to psychological adjustment (Gloria et al., 2009). We postulate that a similar situation would occur for religious congruity, whereby religious congruity is associated with one’s sense of belonging and psychological wellbeing. Hence, similar to cultural incongruity that is related to psychological distress, depressive symptoms, increased substance use, and decreased self-esteem (e.g., Cano et al., 2014), experiencing religious incongruently would result in similar challenges.

The concept of congruity is taught in Islam that encourages tolerance, peace, kindness, and acceptance. The Qur’an advises the unity of mankind: “The believers are but a single Brotherhood. Live like members of one family, brothers and sisters unto one another” (49:10); and mutual respect among people of different faiths: “Respect and honor all human beings irrespective of their religion, color, race, sex, language, status, property, birth, profession/job.…” (17:70). Striving to live in harmony within one’s community is valued in Islam. Religious congruity could contribute to feeling accepted and add to communal harmony and personal wellbeing. The lack of congruity may foster feelings of isolation, tension, and PRBD.

Dyadic CopingDyadic coping refers to the shared process of managing stress in relationships that involves partners’ joint efforts of problem-solving, providing emotional support, and facing the difficulties of life as a couple (Bodenmann et al., 2006). Studies have demonstrated that positive dyadic coping behaviors strongly predict couple’s relational and personal wellbeing (e.g., Rusu et al., 2015). Coping as a couple significantly reduced partners’ distress, fostered marital satisfaction, increased relationship stability, and buffered the effects of stress on relationship quality. The concept of dyadic coping is found in the Qur’an: “Cooperate with one another in good deeds and abstain from evil” (5:2).

This study examined how Muslim couples cope with PRBD and how these experiences affect their romantic relationships. The following hypotheses were tested:

H1: Religious congruity and clothing/grooming styles will be linked to PRBD.H2: PRBD will be positively linked to negative interaction.H3: The effects of PRBD on relationship satisfaction will be mediated by negative interaction that in turn will be moderated by dyadic coping.MethodsParticipantsAmong the 129 heterosexual couples who participated in this study, 95 percent were married (see Table 1). Relationship duration in the period studied averaged 11.81 years (SD = 8.95; Range = 1 to 42.75 years) and the mean age of participants was 39.10 (SD = 9.65; Range = 18 to 70) for men and 35.50 (SD = 8.14; Range = 18 to 61) for women. Most participants were born in North America (45% for women and 42% for men), with remaining participants having origins in the Middle East (16% for women and 20% for men), Asia (22% of women and 21% of men), Africa (7.8 % for women and 7% men), Europe (5.5% for women and 7.8% for men), and Central/South America (3% for women and 2.3% for men). The majority of participants identified as White European (men = 40.3%, women = 41.9%), a quarter identified as Asian (men = 24%, women = 26.4%), about one fifth as African American/Black (men = 19.4%, women = 17.1%), less than one tenth identifies as Arab (men = 7.8% and women = 7.8%), and the rest of the participants were identified as ‘other’ (men = 8.5%, women = 6.8). More men (78%) than women (58%) were fully employed and had completed at least a bachelor’s degree (men = 71%, women = 61%). The average annual household income was from $60,000 to $69,999 with men earning higher wages compared to women.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 129)

VariablesMenWomenM or %SDM or %SDAge [R = 18 to 71 (men) and 18 to 61(women)]39.359.6534.58.14Education:Less than high school1.6%-3.1%-High School Diploma7.8%-7.1%-Some College8.5%-17.1%-2 year degree10.9%-11.6%-4 year degree38.8%-41.1%-Graduate Degree32.5%-21.2%-Employment Status:Full-time79.8%-37.2%-Part-time10.1%-20.2%-Unemployed3.9%-33.3%-Retired3.1%-1.6%-Student3.1%-7.0%-Income Level:Less than 19.9996.2%-8.0%-$20,000-$39,99921.8%-23.3%-$40,000-$59,99912.4%-17.1%-$60,000-$79,99925.6%-22.5%-$80,000-$99,9997.0%-8.6%-$100,000 or Above27.1%-21.8%-Birth Country:North America41.9%-45%-Central/South America2.3%-3.1%-Asia20.9%-21.7%-Middle East20.2%-16.3%-Africa7.0%-7.8%-Europe7.8%-5.5%-Race/EthnicityArab7.8%-7.8%-White European40.3%-41.9%-African American19.4%-17.1%-American Indian/ Pacific Islander3.1%-1.6%-Asian24.0%-26.4%-Non-White Hispanic3.9%-3.1%-Other1.6%-2.4%-Age moved to the U.S.:Before 18 years old24.0%-34.7%-Between 18–26 years old29.3%-33.3%-Between 27–36 years old32.0%-26.4%-37 years old and older14.6%-6.3%-Clothing/grooming style:Very traditional7 %-13.2%-Moderately traditional11.6 %-41.1%-Moderately western28.7 %-22.5%-Western52.7 %-23.3%-Data CollectionQualtrics Panel recruited 120 couples, as this system allowed access to a broader national sample. Nine couples were recruited through the authors’ acquaintances. Participants had to identify as a heterosexual Muslim couple aged 18 and older, reside in the United States, and complete an English-language online survey. Payment was made to Qualtrics for completed surveys who in turn remunerated participants. Participants were instructed to provide consent to voluntarily participate before proceeding to the survey.

Both partners within the marriage completed the survey. After one member of the marriage completed the first section of survey, the spouse used the same link to complete the second half of the survey. Both parts of the survey had identical questions. Spouses were not able to review their partners’ responses. The survey did not time out and based on the computer ID, each computer was allowed to only complete the survey once, eliminating duplicates.

MeasuresReligious Congruity. The 13-item Cultural Congruity Scale (CCS; Gloria & Kurpius, 1996) assessed the degree one’s religiosity fit with one’s surroundings and the degrees to which religious differences were salient. The CCS previously measured Latino students’ fit within the college environment. For this study, the words “ethnicity” and “school” were changed to “Muslim” and “society.” For example, “I feel that I have to change myself to fit at school,” became “I feel that I have to change myself to fit in society.” Items were rated from 1(not at all) to 7(a great deal), with higher total mean scores indicating higher levels of religious congruity. For this study, α = .86 for women and α = .83 for men.

Clothing/Grooming. To assess clothing/grooming styles, a series of images were presented to participants who were asked to identify the style that most fit their everyday look. Men had four choices: 1) long beard, white dress, and turban, 2) long shirt, short beard, and religious cap, 3) Western clothes and facial hair, and 4) Western clothes and no facial hair. Women had five choices: 1) long dark dress with niqab (i.e., only eyes exposed), 2) long dress and long hijab, 3) Western clothes and hijab, 4) Western clothes and hijab partially covering hair, and 5) Western clothes and no hijab. For women, images 1 and 2 were coded 1, the remaining were coded 2 to 4. For men, images were coded 1 to 4. For both genders, lower numbers reflected traditional style and higher numbers reflected Western style.

Perceived Religion-based Couple Discrimination. The Everyday Discrimination Scale was developed to capture interpersonal discrimination (Williams et al., 1997) and the version modified by Trail and colleagues (2012) was used in this study. The modified scale included six of the nine original items. There are various modified versions of the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) having different numbers of items (e.g., Chan et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012) or different response formats (e.g., Jang et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2012). Most recently, a modified EDS was used to measure race-based discrimination that showed high reliability (.93 and .96, Baptist et al., 2018). This is the first known study to use the EDS to measure PRBD: “How often have you experienced the following examples of discrimination by virtue of being a Muslim couple? 1) being treated as inferior, 2) people acting fearful of you, 3) being treated with less respect than others, 4) people treating you as if you have been dishonest, 5) being insulted or receiving name-calling, and 6) being threatened or harassed.” Using a 1(never) to 4(often) scores, higher total mean scores indicated more PRBD. For this study, α = .96 for both women and men.

Negative Interaction. The 4-item Communication Danger Signs Scale (Markman et al., 2010) assessed negative interaction within the couple’s relationship. Items such as, “Little arguments escalate into ugly fights with accusations, criticisms, name calling, or bringing up past hurts,” were scored 1(never) to 6(all the time). Higher total mean scores indicated higher levels of negative interaction. The internal consistency for this scale was .80 (Markman et al., 2010). For this study, α = .89 (men) and .87 (women).

Dyadic Coping. The 5-item common dyadic coping subscale of the Dyadic Coping Inventory (Bodenmann et al., 2006) assessed how couples collaborated as they managed stressful situations. Items such as, “We help each other to put the problem in perspective and see it in a new light,” were rated from 1(never) to 5(very often). Higher total mean scores indicated higher levels of dyadic coping. Internal consistency of this subscale was .83 (e.g., Bodenmann et al., 2006). For this study, α = .90 for men and .91 women.

Relationship Satisfaction. The 4-item Couple Satisfaction Inventory (Funk & Rogge, 2007), measured relationship satisfaction. Items such as, “How rewarding is your relationship with your partner?” were rated from 1(not at all) to 6(completely). Total mean scored were computed where higher scores indicated greater satisfaction. The CSI was found to demonstrate strong convergent and construct validity with other satisfaction measures and good reliability (α = .94) (Funk & Rogers, 2007). For this study, α = .94 for women and α = .90 for men.

Religiosity. The 5-item Centrality of Religiosity Scale (Huber & Huber, 2012) assessed religiosity. Participants rated the frequency they practiced religion (e.g., “How often do you think about religious issues”) and their religious conviction (e.g., “To what extent do you believe that God or something Divine exists?”). Items were recoded so that higher total mean scores indicated greater religiosity, this study’s results being men’s α = .75 (M = 4.26, SD = .92) and women’s α = .68 (M = 4.23, SD = .88). Given the scales range (1 to 6), participants’ average level of religiosity was above average.

The study controlled for the compounding effects of relationship length (in months), income level (in increments of $10,000), age (in years), education level, and number of children, all found to be associated with satisfaction (e.g., Bryant et al., 2010). Geographical location was also controlled for to account for any influence on PRBD.

Data AnalysisDifferences on all studied variables were examined across gender, geography, and clothing/grooming styles using SPSS Version 25 (IBM, 2017). It was anticipated that PRBD, negative interaction, dyadic coping, and satisfaction would be highly correlated given the interdependence within romantic relationships. Next, Measurement Model (without interaction terms) was tested to determine if the model fit the data using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Variables were mean-centered to avoid probability of high multicollinearity with the interaction variable (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). Evidence of fit between the model and the observed data was determined by a nonsignificant Chi-square (x2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI)>.95, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The standard common-fate method or also known as latent group model was used for variables that affect both members of the couple such as dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction. This method was introduced by Kenny and La Voie (1985) and is considered the most appropriate method of measuring between-dyad variables. The model consists of latent variables that are measured by separate indicators for each member of the couple. Essentially, the model decomposes the relationship between variables into a dyad-level relations and two individual-level relations.

The common-fate method is appropriate for questions about the relationship. For example, for dyadic coping: “We help each other to put the problem in perspective and see it in a new light.” Because both partners are asked the same question hence report on the same variable, the construct represents the dyad and is best represented by the common-fate conception (Ledermann & Kenny, 2011). PRBD, satisfaction, and dyadic coping were modeled as joint measures through a common-fate method to account for the shared variance of the couple dyad, reflected by the factor loadings of the latent construct. Religious congruity was specified by two indicators, one each for women and men.

Next, a Structural Model (Model 2) with interaction terms tested the moderating effects of dyadic coping on negative interaction. Model 1 was compared Model 2 using a x2 difference test (TRd) based on log-likelihood values and scaling correction factors obtained with the robust maximum likelihood estimator (Satorra & Bentler, 2010). Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) indices further helped determine model fit, whereby lower values indicated better fit (Little et al., 2006).

ResultsPreliminary AnalysisIntercorrelations results (Table 2) suggested that men’s and women’s dyadic coping, satisfaction, negative interaction, and PRBD were significantly related to each other, hence justifying the use of a common-fate latent model. For both men and women, PRBD was positively related to negative interaction and negatively related to religious congruity. Satisfaction was significantly associated with dyadic coping and negative interaction. PRBD and satisfaction were not related for either gender.

Table 2. Summary of Intercorrelations of Study Variables (N = 129)

Variables1234561. Relationship Satisfaction.67***-.29***.60***-.05.11.062. Negative Interaction-.35***.81*** -.27**.42***-.42***-.053. Dyadic Coping.69**-.30***.79***.06-.11.024. Discrimination-.04.38***.10.80***-.44***-.29*** 5. Religious Congruity.03-.40***-.14-.50***.67***.05 6. Clothing/grooming style.09-.10.11-.18*-.001.46***Women:M5.042.503.751.8513.192.56 SD1.211.401.04.93.65.99Men:M5.082.524.521.8613.184.25 SD1.251.371.27.95.88.92Note. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. (two-tailed). Men = above the diagonal. Women = below the diagonal. Intercorrelations between men and women across the diagonal. Discrimination = Perceived religion-based couple discrimination. Negative Interaction = Couple negative interaction.

Examination of group differences. Results of t-tests indicated that men reported higher dyadic coping [t(246) = 5.65, p < .001, 95%CI = .53, 1.10] and adorned more Western clothing/grooming styles [t(256) = 5.97, p < .001, 95%CI = .47, .94] compared to women. There were no other gender differences. Results of ANOVAs indicated that PRBD differed across clothing/grooming styles for men, F(3,123) = 5.23, p = .002. Post hoc analyses using the Games-Howell criterion indicated the PRBD was significantly higher in men who had long beard and wore long dress and rounded skullcap (M = 16.89, SD = 5.08) than in men with no facial hair who wore Western-styled clothing (M = .43, SD = 5.53). There were no significant differences in PRBD across women’s clothing/grooming styles (F(4,122) = 1.76, p = .14). There were also no significant differences in PRBD for geography and race/ethnicity for men and women.

Model Fit. The estimation of the measurement model fit was poor (CFI = 91, TLI = .88, x2(117) = 185.26, p < .001, RMSEA = .07). To improve fit, the path from PRBD that had no direct effect on satisfaction (β = -.70, p = .34) was removed. This did not change the model fit. Next, control variables were sequentially removed to improve model fit. The fit improved after removing only age (CFI = .95, TLI = .94, x2(96) = 127.43, p = .02, RMSEA = .05), suggesting that the fit was acceptable for the observed data.

Next, TRd was computed using the log-likelihood values of -1800.61 (Model 1) and -1796.76 (Model 2), scaling correction factors of 1.31 (Model 1) and 1.32 (Model 2) and free parameters of 54 (Model 1) and 55 (Model 2). The TRd of 3.91 for 1 df was significant at the .05 level, suggesting that Model 2 better fit the observed data compared to Model 1. Model 2’s AIC and BIC were also lower than that of the Model 1, making the former the final model. Model 2 accounted for 74% of the variance in satisfaction, 25% in negative interaction, and 41% in PRBD. Results are presented in Table 3.

Main AnalysisH1: religious congruity and clothing style will be linked to experiencing religion-based discrimination, was fully supported for men and partially supported for women. For both men and women, feeling that one’s religious values fit with that of the community’s was negatively linked to PRBD (Men: β = -.28, p = .008; Women: β = -.31, p = .004). Additionally, PRBD was found to negatively relate with men’s clothing/grooming style (β = -.21, p = .02). In other words, men who wore more Western-style clothing reported less PRBD compared to men who wore more traditional-styled clothing. Women’s clothing/grooming styles was not related to PRBD.

Table 3. Results of Moderated Mediated Model of Perceived Religion-based Couple Discrimination on Relationship Satisfaction

Model 1Model 295% CIbSEβbSEβCouple Discrimination :Men1.00.00.881.00.00.87***.78, .96Women1.04.13.911.05.13.91***.81, 1.01Relationship Satisfac.:Men1.00.05.741.00.00.72***.58, .87Women1.16.16.871.18.18.87***.80, .95Dyadic Coping:Men1.00.00.871.00.00.86***.79, .93Women1.06.10.921.07.09.92***.86, .98Couple negative interaction:Men1.00.00.991.00.00.95***.86, 1.05Women.82.10.81.89.11.85***.75, .95Paths to Couple Discrimination:R2= .41, p< .001Men Clothing/grooming-.20.09-.21*-.20.09-.21*-.37, -.06Women Clothing/grooming-.09.06-.11-.09.06-.11-.25, .02Men Religious Congruity-.25.09-.29**-.24.09-.28**-.46, -.11Women Religious Congruity-.26.09-.30***-.27.09-.31***-.48, -.13Control Variables:Men Education Level-.002.07-.003-.001.06-.001-.18, .17Women Education Level-.005.05-.01-.004.05-.007-.14, .13Number of Children-.11.13-.07-.10.13-.07-.21, .08Household Income.04.02.14.04.02.14.00, .28Duration of Relationship-.003.01-.03-.003.01-.03-.16, .10Paths to Couple Negative Interaction:R2= .25,p = .002Couple discrimination.56.11.49***.55.12.50***.36, .63Paths to Relationship Satisfaction:R2 = .74,p < .001Couple negative interaction-.13.05-.18*-.17.08-.24*-.40, -.07Dyadic Coping.70.09.83*** .81.181.01***.77, 1.29Couple negative interaction × Dyadic Coping---.18.10.21*.04, .38Fit Indices:AIC3709.223703.52BIC3863.653860.81x2(96)127.42 (p = .02)RMSEA.05CFI.95TLI.94Note. Satisfac. = Satisfaction. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Couple Discrimination = Perceived religion-based couple discrimination.

H2: religion-based discrimination will be positively linked couples’ destructive communication patterns, was fully supported. Results revealed that more PRBD is associated with more negative interactions between couples (β = .50, p < .001). In other words, as couples PRBD increased, their negative interactions increased.

H3: the effects of religion-based discrimination on couples’ relationship satisfaction is mediated by communication quality that in turn is moderated by couples’ joint dyadic coping, was partially supported. On average, couples who experienced more negative interactions reported lower satisfaction (β = -.24, p = .018). The evidence that this relationship varied based on dyadic coping was significant and varied based on level of dyadic coping (β = .21, p = .04). In other words, the effect of negative interaction on satisfaction depended on dyadic coping.

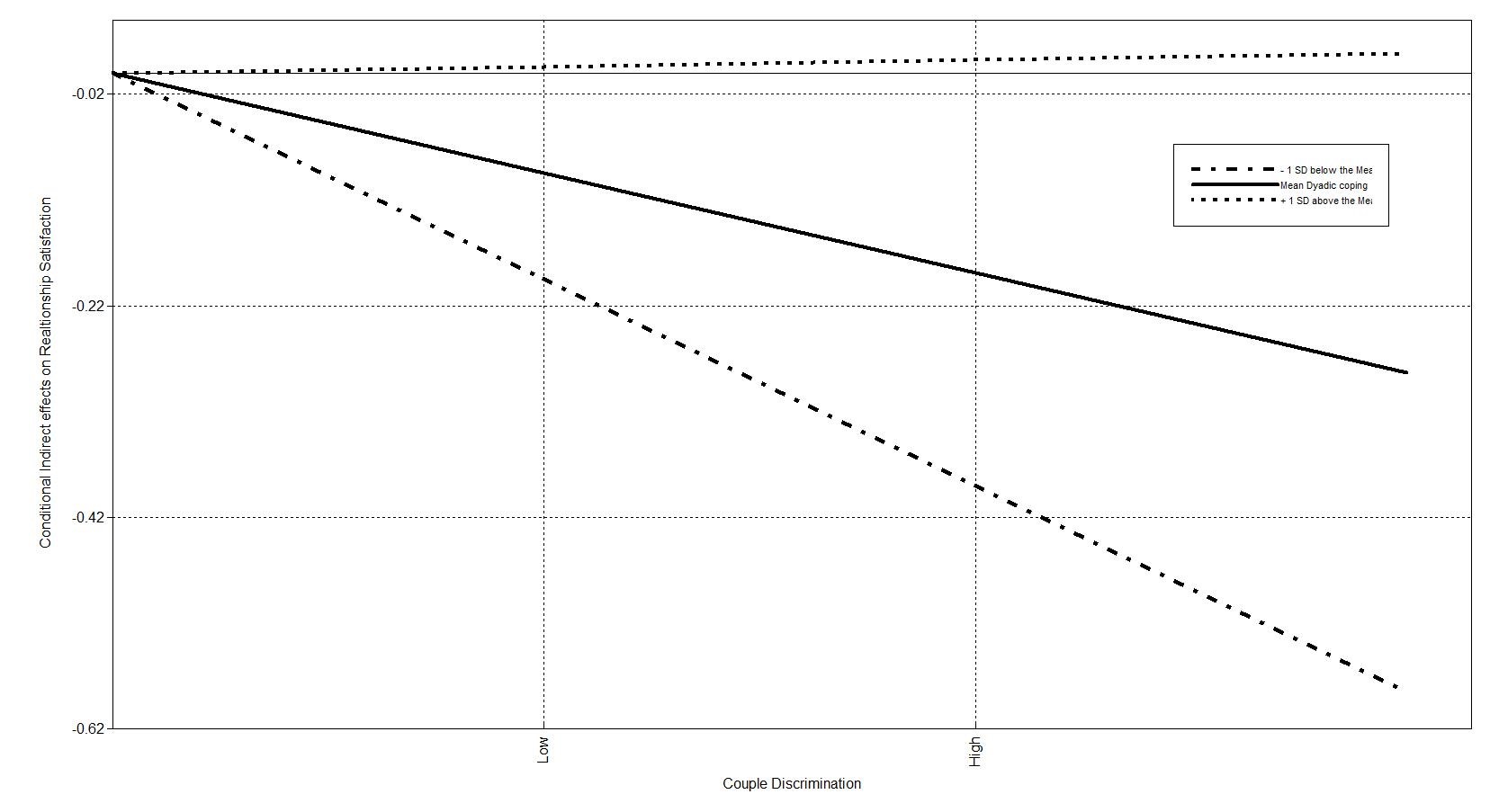

A formal test of the indirect effect is measured by the index of moderated mediation, which was significant (b = .10, Z = .83, p = .07, 95%CI = .01, .09) at the .01 level. The CI does not include a zero; meaning that the indirect effect of PRBD on satisfaction through negative interaction was an increasing function of dyadic coping. Results further indicated significant indirect effects of PRBD on satisfaction through negative interaction when dyadic coping was 1 SD below the mean (b = -.20, Z = -2.04, p = .04, 95%CI = -.35, -.04) or at the mean (b = -.09, Z = -2.08, p = .04, 95%CI = -.17, -.02), but 1 SD above the mean (b = .01, Z = .20, p = .85, 95%CI = -.05, .06) (Figure 2). Results suggested that the mediating effect of negative interaction fluctuated as dyadic coping fluctuated.

Figure 2. Levels of dyadic coping on the indirect effects of perceived religion-based couple discrimination on relationship satisfaction.Discussion

Figure 2. Levels of dyadic coping on the indirect effects of perceived religion-based couple discrimination on relationship satisfaction.DiscussionThis study examined the relationship between religious congruity and clothing/grooming styles with PRBD and how dyadic coping moderates the indirect effect of PRBD on satisfaction through couple negative interaction. First, it would be important to preface this discussion with the fact that although the participants in this study indicate that religion was important to them (based on their religiosity scores), participants may interpret the teachings of the Qur’an differently. The discussion below is based on the premise that Qur’anic teachings are interpreted as a resource that can strengthen relationships.

The results suggest that when couples experience their community as accepting of their Muslim culture, they are less likely to perceive themselves as targets of PRBD. This finding supports previous studies where having a Muslim identity that is accepted by society at large may buffer the odds of PRBD (Jasperse et al., 2012). Feeling a sense of belonging and acceptance by society may contribute to reduced vigilance for discrimination or increase the likelihood of brushing off discriminatory acts, not believing that such actions could have ill intent. The Holy Qur’an stresses collective identity and inclusion. Thus, it is likely that in order to maintain their relationships, Muslim couples may tend to perceive that others hold a positive view of them that, in turn, could prompt the denial or hesitation to consider any unjust treatment as discrimination.

Further, acknowledging and accepting the faith and opinions of all people is encouraged as stated in the Qur’an: “We have appointed a law and a practice for every one of you. Had God willed, He would have made you a single community, but He wanted to test you regarding what has come to you. So compete with each other in doing good...” (5:48). Because intolerance, violence, and holding grudges are against Islamic teachings, Muslims who regulate their life based on Qur’an may be more likely to excuse PRBD or brush aside their encounters with discriminatory acts.

The relationship between clothing/grooming styles and PRBD is consistent with previous research where overt markers of Islam were found to be more likely targets for discrimination (e.g., Fozdar, 2011). This could be related to media’s promotion and the profiling of men dressed in traditional Muslim clothing as potential terrorists (Hoewe, 2014). Interestingly, unlike previous studies that found Muslim women experience more acts of discrimination than men (e.g., Rahmath et al., 2016), the present study found that women’s clothing/grooming styles were not linked to PRBD. This finding may be related to women’s employment status. More Muslim women than me in the present study were not fully employed outside the home, perhaps inadvertently protecting them from overt discrimination. Reduced encounters with the general public may mean fewer opportunities to meet persons who are outwardly discriminatory. Another possible explanation for this finding might be that many participants in this study are from the Northeast (42 women), a largely metropolitan, culturally and religiously diverse part of the United States. Women who wear hijab may not be a novelty in this region of the country and thus may not stand out in the crowd or attract undue attention.

As expected, feeling discriminated against as a couple was linked to the couples’ negative communication patterns. This result is consistent with the literature on stress in intimate relationships and relationship functioning (e.g., Feinstein et al., 2018). It appears that partners’ perception of discrimination is related to lower quality of interactions (e.g., Lau et al., 2019). Previous studies on minority couples indicate that prejudice and discrimination impairs intimate relationships that then adversely affect the quality of romantic relationships (e.g., Baptist et al., 2018). Discrimination is a form of stress and when it is experienced by either partner, it can contribute to interpersonal conflict that in turn can lead to more frustration and negativity, less warmth, and decreased efforts to maintain a close bond (e.g. Randall et al., 2009). Both the Stress Process Model (SPM; Pearlin et al., 1981) and Race-based Traumatic Stress Theory (RBTST; Carter, 2007) support this finding. Discrimination, a form of psychological trauma, can lead to avoidance, isolation, opposition, and irritability that can spill over into couples’ relationships and lead to anger, helplessness, fear, hostility, verbal aggression, and frustration. These destructive interactions can exacerbate the harmful effects of discrimination which ultimately results in poorer relationship outcomes. In other words, couples’ strained interactions can contribute to other relationship problems and lower overall satisfaction with their relationship. It is important to note that while negative interactions within the couple relationship was related to lower satisfaction in the current study, PRBD was not directly linked to satisfaction. It is possible that direct effects might emerge in a larger sample.

The results suggest that dyadic coping buffers the effects of PRBD on satisfaction when negative interactions exist but only when dyadic coping is at above average levels. These couples appear to be resilient to PRBD. However, when dyadic coping is at average or below average levels, variations in the level of PRBD significantly changes the level of satisfaction when there is negative interactions in the couple relationship. Congruent with the SPM, the findings suggest that couples with high dyadic coping skills are able to manage conflict together and possibly change the personal meaning of either the stressful experience or situation itself (Pearlin et al., 1981). For those couples who report PRBD, dyadic coping can serve as a protective mechanism by promoting trust, support, and care provided the level of coping is sufficiently high. The findings of this study are consistent with the few previous investigations in this area (e.g., Rusu et al., 2015). The current findings confirm that negative interactions can be deleterious to intimate relationships for Muslim couples, but these relationships reduce in significance when partners have high levels of joint coping skills.

Limitations and Future DirectionsThis study has several limitations. First, the measure for PRBD includes frequency but not intensity. Future studies should assess both the intensity and frequency in order to provide a more accurate assessment of stressful experiences and their impacts. Second, because no time frame was indicated in the scale, it may not have adequately captured the cumulative effects that discrimination can have on relationship outcomes. More sophisticated measures of PRBD should be employed in future research. Third, cross-sectional designs provide only a snapshot in time that makes the casual relationship problematic between variables. Further, PRBD might be different over time in response to various social events and using longitudinal designs in future research would be valuable. Fourth, the small sample in this study limits the ability to examine additional paths and include other relevant variables. Replicating this study with a larger sample would allow inclusion of other relationship processes (e.g., positivity, openness, commitment, and problem-solving) that could contribute to Muslim couples’ ability to preserve their relationships and cope with stress from discrimination.

ImplicationsThe results provide important information for interventions with Muslim couples seeking to enhance their relationships and manage any PRBD. It is important for clinicians working with Muslim couples to be aware of the adverse consequences of PRBD and its potential to strain relationships. It may be particularly important to be aware that men who dress in traditional Muslim clothing may report more PRBD especially if they do not feel accepted by their community. Because feeling accepted as a Muslim can potentially reduce PRBD, assessing for belonging is recommended to ascertain clients’ needs. Muslim clients who present with low belongingness and are new to the United States could benefit from being connected to other Muslims in the community as well as with resources that are Muslim-friendly that offer opportunities to connect with neighbors.

Second, PRBD can have negative implications on couple relationships. It becomes important for clinicians working with Muslim couples to assess their perceptions of discrimination that could be the precursor to conflict within their relationship. To facilitate this discussion, clinicians need to create a safe environment for couples to share these perceptions. Third, developing couples’ collaborative coping skills can serve as a protective mechanism for the relationship against the indirect effects of PRBD. Clinicians working with Muslim couples could help enhance couples’ dyadic coping strategies, encouraging habits like mutual empathy and helping each other to engage in problem-solving to reduce stress and increase satisfaction. Couples can further be coached to use more constructive means of communication to resolve conflicts more effectively.

The findings have implications for local religious leaders and organizations who can play an important role in advocating for improved acceptance and understanding of diversity. Through their imams and governing boards, mosques and Islamic centers can promote understanding of Islam and Muslims in their local communities. Likewise, local churches can facilitate interreligious dialogue as a means to embrace fellow Muslims in their community. Schools and medical centers can better educate their staff to identify signs of distress and provide appropriate referrals. These institutions can assist with improving religious congruity for Muslims by providing designated prayer rooms, access to interpreters and translated materials, and displaying artwork that are inclusive and broadly representative. Communities can recognize their Muslims residents by noting Muslim holidays and providing time off to their Muslim staff to attend religious gatherings on those days.

Clinicians need training to be attuned to their own perceptions regarding Islam and Muslims in order to ensure that services provided are not infused with prejudice or ignorant presuppositions. Because prejudicial treatment can often be covert and manifest as microaggressions, it would be important for clinicians to be aware of how they come across when working with Muslims. Identifying commonalities with the Muslim community in order to demystify Islam and Muslims and to combat misinformation could be a first step toward support and allyship. Immersion experiences that provide opportunities to connect with Muslims and experience religious practices can help reduce anxiety and increase comfort and the ability to empathize.

ConclusionThis study provides insight into how Muslim couples’ levels of PRBD is associated with satisfaction. The findings provide preliminary evidence that perceiving that one’s religion is accepted by the community and for men only, adorning Western-styled clothing was related to less PRBD. Additionally, this study suggests that PRBD is directly related to conflictual interaction between couples which can reduce their satisfaction. In other words, PRBD has an indirect effect on satisfaction through negative couple interaction. This indirect effect can to be buffered by couples’ joint coping skills only when these skills are sufficiently developed. This study makes an important contribution to the literature while providing a foundation for others to build upon.

ReferencesAbu-Ras, W., Suárez, Z. E., & Abu-Bader, S. (2018). Muslim Americans’ safety and well-being in the wake of Trump: A public health and social justice crisis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(5), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000321Ahmed, S. R., Kia-Keating, M., & Tsai, K. H. (2011). A structural model of racial discrimination, acculturative stress, and cultural resources among Arab American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9424-3Baptist, J., Craig, B., Nicholson, B. (2018). Black–White marriages: The moderating role of openness on experience of perceived religion-based discrimination and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12362Bell, G. C., & Hastings, S. O. (2011). Black and white interracial couples: Managing relational disapproval through facework. The Howard Journal of Communications, 22(3), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2011.590405Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., & Kayser, K. (2006). The relationship between dyadic coping, marital quality and well-being: A 2-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(3), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485Bryant, C. M., Wickrama, K.A.S., Bolland, J., Bryant, B. M., Cutrona, C.E., Stank, C. E. (2010). Race matters, even in marriage: Identifying factors linked to marital outcomes for African Americans. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 2(3), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00051.xCano, M. A., Castillo, L. G., Castro, Y, de Dios, M. A., & Roncancio, A. M. (2014). Acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among Mexican and Mexican American students in the US: Examining associations with cultural incongruity and intragroup marginalization. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-013-9196-6Carter, B. G. (2010). The strengths of Muslim American couples in the face of religious discrimination following September 11 and the Iraq War. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 80(2–3), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2010.481462Carter, R.T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizi

留言 (0)