Int J Biol Sci 2021; 17(1):271-284. doi:10.7150/ijbs.50003

Review

Xue-yin Pan1,2,3, Cheng Huang1,2,3, Jun Li1,2,3 ![]()

1. Inflammation and Immune Mediated Diseases Laboratory of Anhui Province, Anhui Institute of Innovative Drugs, School of Pharmacy, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, 230032, China.

2. The Key Laboratory of Anti-inflammatory of Immune Medicines, Ministry of Education.

3. Institute for Liver Diseases of Anhui Medical University.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions.

Citation:

The 'epitranscriptome', a collective term for chemical modifications that influence the structure, metabolism, and functions of RNA, has recently emerged as vitally important for the regulation of gene expression. N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most prevalent mammalian mRNA internal modification, has been demonstrated to have a pivotal role in almost all vital bioprocesses, such as stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, heat shock or DNA damage response, tissue development, and maternal-to-zygotic transition. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is prevalent worldwide with high morbidity and mortality because of late diagnosis at an advanced stage and lack of effective treatment strategies. Epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation and histone modification have been demonstrated to be crucial for liver carcinogenesis. However, the role and underlying molecular mechanism of m6A in liver carcinogenesis are mostly unknown. In this review, we summarize recent advances in the m6A region and how these new findings remodel our understanding of m6A regulation of gene expression. We also describe the influence of m6A modification on liver carcinoma and lipid metabolism to instigate further investigations of the role of m6A in liver biological diseases and its potential application in the development of therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Epitranscriptome, N6-methyladenosine, Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

To date, more than 170 types of RNA modifications have been identified, including 5' cap modification, poly(A) tail, pseudouridine (Ψ), N1-methyladenosine (m1A) and N6,2'-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), and N6-methyladenosine (m6A) [1]. Among these modifications, m6A is the most abundant internal RNA modification in eukaryotic cells that widely occurs in mRNA [2] and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [3-11]. Numerous studies have provided evidence that m6A is involved in fundamental physiological and pathological RNA metabolic processes, including splicing, nuclear export, stability, translation, and decay [12-16]. These studies advanced our understanding of m6A function and regulatory mechanisms in various human diseases.

m6A is highly conserved among eukaryotic species ranging from yeast [17,18], plants [19], and drosophila viruses [20,21] to mammals [22,23]. However, the m6A filed did not progress for several decades until the availability of MeRIP-seq or m6A-seq techniques [24,25]. Consensus motif analyses revealed that m6A sites depicted as “DRACH” motif (R = G or A; H = A, C, or U; where A is converted to m6A) in the transcriptome is not random but occurs in coding sequences (CDS), 3'-untranslated regions (3'-UTRs), and especially in the region around the stop codon [24,25]. Despite the prevalence of DRACH sequences in the transcriptome, only 1-5% of these sites are methylated in vivo, indicating that the DRACH motif itself is not sufficient to determine m6A deposition.

m6A modification is induced by m6A methyltransferase complex (composed of METTL3/METTL14/METTL16, WTAP, KIAA1429, ZC3H13, HAKAI, and RBM15/15B) [26-28], removed by m6A demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5) [29,30], and recognized by RNA binding proteins, including YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2, IGF2BP1/2/3, hnRNPs [14,16,31-39]. m6A modification of U6 snRNA and structural RNA, 18 S rRNA and 28 S rRNA, the 5'cap m6Am, and U2 snRNA internal m6Am are methylated by METTL16 [10,11,40], METTL5 [41], ZCCHC4 [9,42] and PCIF1 [43,44], respectively. Recently, METTL4 was shown to be a U2 snRNA internal m6Am methyltransferase [45].

It has been demonstrated that m6A modification influences gene expression and is involved in a variety of human cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [46]. In terms of high morbidity and mortality, HCC ranks the second highest cancer [47,48]. Multiple factors can trigger or worsen the pathology of HCC, including chronic hepatitis B and C viral infection, chronic alcohol consumption, obesity, metabolic disorders, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [49]. Surgical resection is the only curative therapy and sorafenib is the only approved drug for the treatment of HCC. The survival rate is up to 70% in patients with a tumor size of less than 2 cm [50]. Therefore, early diagnosis is essential for HCC treatment. Numerous studies have demonstrated an important role of epigenetic modifications including DNA and histone modification in regulating HCC progression [51]. There is increasing evidence that total m6A levels and abnormal expression of m6A regulators are altered and associated with HCC clinical prognosis [52,53]. Furthermore, the m6A modification regulators play an oncogenic or tumor suppressor role in HCC by influencing the expression of special genes [54-56]. Therefore, in this review, we focused on recent progress in m6A detection, the function and the mechanism of m6A regulators in lipid metabolism, hepatic virus infection, and liver carcinogenesis, and it may provide a potential novel therapeutic and prognosis targets for HCC.

The global levels of m6A in total RNA can be detected by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS), dot-blot analysis [29], and m6A Methylation Quantification Kit [12,29]. The most commonly used approach for detecting transcriptome-wide m6A levels is MeRIP-seq [24] or m6A-seq [25] that can detect m6A sites in a 100-200 nt resolution. Then the SCARLET method was developed to qualify the m6A levels of individual modification sites [57] but it is not feasible for high-throughput applications. Subsequently, MeRIP-seq and m6A-seq methods were improved with an added ultraviolet crosslinking step to identify m6A sites at the single-nucleotide resolution termed PA-m6A-seq (photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing strategy) [58,59] or m6A-CLIP-seq (UV cross-linked m6A antibody-bound RNA sample) [60,61]. Then, MAZTER-seq and m6A-REF-seq, were developed that relied on MazF RNase or ChpBK RNase by two independent groups [62,63]. However, MATER-seq or m6A-REF-seq sensitive to m6A sites occurs only in the ACA motif context. DART-seq, which rely on the cytidine deaminase APOBEC1 refused with YTH domain contain protein was used to induce C to U deamination at sites adjacent to m6A residues [64]. However, the quality of DART-seq relies on transfection efficiency, and its application is limited. DAPT-seq also loses some m6A sites and has higher false-positive and false-negative rates. Recently, an FTO-assisted m6A selective chemical labeling method (termed m6A-SEAL) was developed [65]. However, the resolution of m6A-SEAL is about 200 nt which needs to be improved in the future. In m6A-label-seq method, Se-allyl-l-selenohomocysteine substituted the methyl group with allyl on SAM [66]. Subsequently, cellular RNAs were modified with N6-allyladenosine (a6A) at the presumed m6A-generating adenosine sites and will be further pinpointed by iodination-induced misincorporation at the opposite side in the complementary DNA during reverse transcription. The rapid development of m6A detection method will greatly accelerate the discovery and validation of m6A modification sites in human genome species, which will further facilitate the development of new biomarkers for cancer prognosis and classification.

As showed in Figure 1, m6A modification can be induced by m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC, also known as m6A 'writers') [67,68], which is composed of the core catalytic subunit METTL3/METTL14 [67] and regulatory proteins, including WTAP, VIRMA, ZC3H13, HAKAI, RBM15/RBM15B [28,69]. Unlike METTL3 complex that preferentially methylates single-stranded RNAs (ssRNAs), METTL16 functions alone and selectively methylates structured RNAs in the UACAGAGAA sequence [40]. Recently, METTL5 is reported to catalyze m6A modification in 18 S rRNA at position A1832, and ZCCHC4 induces m6A sites in 28 S rRNA at position A4220, and METTL5 is stabilizes by TRMT112 [9,41,42]. The cap structure, 7-methylguanosine (m7G), is linked to the first transcribed nucleotide (X) that is methylated at the ribose O2 position. If the first nucleotide is adenosine, it can be further methylated on the N6 position, termed m6Am. m6Am modification adjacent to the m7G cap is a reversible modification catalyzed by PCIF1 (CAPAM, cap-specific adenosine N6-methyltransferase) [43,44,70,71]. METTL4 has recently been identified as a novel internal m6Am methyltransferase responsible for N6-methylation of m6Am30 on U2 snRNA with a preference for the AAG motif [45].

Figure 1The dynamic regulation and function of m6A and m6Am. The m6A modification is methylated by the methyltransferase complex (MTC, also known as m6A 'writer'), composed of the core catalytic subunit METTL3-METTL14 and the regulator proteins WTAP, VIRMA, ZC3H13, RBM15/RBM15B and so on. METTL16 alone can methylated m6A deposition in structural RNA and snRNA. METTL5 is responsible for m6A deposition in 18 S rRNA and facilitate ZCCHC4 as 28 S rRNA methylase. METTL4 mediate internal m6Am modification in U2 snRNA. m6A modification can be eliminated by m6A 'eraser' (FTO and ALKBH5). The function of m6A is mediated by m6A 'reader', which affects RNA splicing, export, decay, stabilization and translation. YTHDC1 and hnRNPs (hnRNPA2B1, hnRNPC and hnRNPG) facilitate RNAs alternative splicing. The nuclear export of m6A containing RNAs is mediated by YTHDC1 and FMRP. The nuclear YTHDF2 binds with m6A in 5'UTR prevent FTO demethylation and promote cap-independent translation. The decay of m6A modified RNAs is mediated by YTHDF2/YTHDF3 and YTHDC2. The translation is facilitated by YTHDF1/YTHDF3, IGF2BP1/2/3, FMRP, METTL3 and YTHDC2. IGF2BP1/2/3, FMRP, PRRC2a and SND1 facilitate to keeping methylated RNAs stability.

The m6A mark may be removed by RNA demethylases (also known as m6A 'erasers'), including FTO and ALKBH5 [12,29]. The identification of FTO suggested that m6A modification is dynamic and reversible [29]. Further studies reveal that FTO can remove m6A and m6Am in mRNA and U6 snRNA, and m1A in tRNA [70,72]. ALKBH5 seems to specific demethylated m6A modification in RNA [12].

m6A is involved in numerous RNA processes, including splicing, export, decay, stability, and translation and exerts its functions mainly by recruiting m6A-binding proteins (also known as m6A 'readers'). As displayed in Figure 1, YTHDC1, hnRNPC, hnRNPG, and hnRNPA2B1 may regulate mRNA splicing by recognizing m6A sites on pre-mRNA in a direct or indirect (also known as “m6A switch”) manner [14,33,38,73]. YTHDC1 and FMRP could mediate nuclear export of m6A modified RNAs into cytoplasm [74-76]. The nuclear YTHDF2 binds m6A sites in 5'UTR and prevents demethylation by FTO and thereby promotes cap-independent translation [77]. In the cytoplasm, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC2 could mediate m6A deposited transcripts degradation in p-bodies, whereas IGF2BP1/2/3, FMRP, Prrc2a, SND1, and HuR play an important role in maintaining m6A-containing transcripts stabilization [35,78-84]. YTHDF1, YTHDF3, YTHDC2, IGF2BP1/2/3, FMRP, and cytoplasm METTL3 promotes m6A deposited mRNA translation [31,32,35,36,85-89]. In summary, m6A influence RNA every aspect of RNA metabolism depending on the functions of various readers.

Why the distribution of m6A sites on DRACH motif is not random but occurs in CDS and 3'-UTR regions, especially around the stop codon, despite the high prevalence of DRACH [25]? Yue et al. demonstrated that VIRMA can interact with WTAP-HAKAI-ZC3H13 to recruit METTL3/METTL14 and guide region-selective methylation in 3'UTR and near stop codon [28]. FTO preferentially targets pre-mRNAs in intronic regions and regulates alternative splicing and 3'end processing [64]. Huang et al. described that Histone H3 trimethylation at Lys36 (H3K36me3) can guide m6A modification globally [90]. H3K36me3 can be recognized and bound directly by METTL14, and then facilitates the binding of MTC to adjacent RNA polymerase II, regulating m6A deposition in actively transcribed nascent RNAs. This study revealed a cross-talk between histone modification and m6A deposition. Several studies indicated that transcription factors can also influence m6A deposition. For instance, ZFP217 interacts with several epigenetic regulators and modulates m6A deposition on their transcripts by sequestering the enzyme METTL3 [13]. The CAATT-box binding protein CEBPZ recruits METTL3 to chromatin and promotes m6A modification within the coding region of the associated mRNA transcripts [91]. The interaction of SMAD2/3 with METTL3/METTL14/WTAP complex mediates m6A modification in a subset of transcripts involved in early cell fate decisions [92]. By using the CRISPR-Cas9 technology, the m6A modification site can be edited by fusing dCas9 (dead Cas9) with single-chain methyltransferase domains derived from METTL3 and METTL14 or full-length of m6A demethylase (ALKBH5 or FTO) [88]. Programmable m6A editing can be realized by this approach providing a mechanistic understanding of epitranscriptome.

Lipid metabolismHCC is the second most frequent cancer in the world with high morbidity and mortality [49]. Viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) progress to HCC. Therefore, the prevention of HCC is focused on averting virus infection (hepatitis B and C viruses), inflammation, and obesity [93]. NAFLD is a risk factor predisposing HCC formation and is associated with metabolic syndromes, including diabetes and obesity. Transcriptome-wide m6A profile has revealed that m6A-containing gene exhibit a high overlap in human HepG2 cell lines and mouse livers. Moreover, m6A-modified regions in liver tissues are enriched of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) related to lipid traits [94]. Functional enrichment analysis of m6A-modified genes in porcine liver at three developmental stages are involved in regulating growth, development, metabolic process and protein catabolic processes [95]. The diverse pattern of m6A-modification on genes in different stage had metabolic functions required for or specific to this stage, which indicating that the liver may be exposed to different stimuli during development. High-fat diet (HFD) induced m6A modification enriched in gene associated with lipid-associated processes, including cellular lipid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, response to fatty acids and TG metabolism [96]. Xie et al. reveals that elevated METTL3 expression in Type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients inhibits hepatic insulin sensitivity via N6-methylation of Fasn (fatty acid synthase) mRNA, and subsequently promotes fatty acid metabolism [97]. Approximately one-tenth of liver genes have been identified as rhythmic, however only one-fifth of those genes are driven by de novo transcription, suggesting that both transcriptional and epigenetic mechanism underlie the mammalian circadian clock [98]. At the core of the mammalian circadian clock gene regulatory network, the bHLH-PAS transcriptional activators BMAL1, CLOCK and NPAS2 activate the Period (Per1, Per2) and Cryptochrome (Cry1, Cry2) genes whose transcripts and proteins slowly accumulate during the daytime [98]. Some circadian clock-dependent pathway involved in regulating both anabolism and catabolism, such as lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism and bile acid synthesis [99]. Recently, a research showed that m6A modification involved in regulating this process, liver-specific deletion of Bmal1 (Bmal1-/-) results in high levels of ROS and elevated oxidative damage, and subsequently ROS significantly elevates METTL3 expression, which finally suppresses PPARα (the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activator α) expression in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner, which will influence the lipid metabolism [100]. Recently, it has been reported that m6A modification enriched in and enhanced the expression of lipogenic genes in leptin receptor-deficient db/db mice, however, YTHDC2 could attenuate lipid metabolic disorder and hepatic TG accumulation by binding and decreasing the stability of lipogenic gene including sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (Srebp-1c), fatty acid synthase (Fasn), stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (Acc1) [101]. m6A modification enhances the stability of LINC00958, and subsequently, elevated LINC00958 sponges miR-3619-5p to upregulate hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) expression, thereby facilitating HCC lipogenesis and progression [102]. FTO is known to be tightly associated with increased body mass and obesity in humans [103-105]. FTO is reported to and positively related to obesity and T2D, and FTO levels were significantly increased in NAFLD group [106,107]. These results reveal that m6A modification involved in regulating lipogenesis and NAFLD, which is a major risk of HCC.

Driving factors in hepatocyte transformation and HCC development are chronic inflammation, epigenetic modifications, early neoangiogenesis, senescence, DNA damage, and telomerase reactivation, chromosomal instability [108]. Liver cancer usually develops only after decades of HCV infection, and often accompanied by cirrhosis. As a positive-strand RNA virus, most if not all events related to HCV replication are restricted to the cytoplasm. Therefore, HCV infection induced longstanding hepatic inflammation with associated oxidative and the potential DNA damage in the presence of cirrhosis is thus likely to contribute to the development of carcinoma [109,110]. HBV contributes to HCC progression through direct and indirect mechanisms. HBV-related HCC, cirrhosis is absent in up to one-third of patient. It has been shown that viral infection can affect m6A modification and thus alter m6A in special transcripts and influence viral infection [111]. m6A modification in the 5′ epsilon stem-loop of pgRNA, which mediates HBV life cycle, is necessary for efficient reverse transcription of pgRNA, whereas m6A sites in the 3′ epsilon stem-loop lead to destabilization of HBV transcripts [112]. This study reveals that m6A modification of HBV RNA exerts dual regulatory functions. m6A modification negatively regulates HCV life cycle and the production of infectious HCV particles, and m6A-binding YTHDF proteins relocalize to lipid droplets, sites of HCV viral assembly, and suppress this stage of viral infection [113]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that HBV infection increases METTL3 and subsequently upregulates m6A modification and degradation of PTEN, which consequently inhibits IRF-3 nuclear import and activation of PI3K/AKT pathway to facilitate HCC progression by affecting innate immunity [114]. Taken together, these studies indicated that m6A modification plays a significant role in broader HBV/HCV virus infection, and uncover regulatory strategies to inhibit replication by these established and emerging viral pathogens to prevent HCC development.

This missegregation of genomic material is defined as Chromosome instability that is associated with poor prognosis of cancer patients including HCC [115,116]. HBV can facilitate HCC progression by inducing both chromosome instability by integrating its DNA into the host genome and mutagenesis of various cancer-related genes [117]. Furthermore, HBx could directly induce chromosomal instability by affecting the mitotic checkpoints through binding and inactivating p53 and DDB1 [118,119]. Not only virus DNA, altered cellular signaling pathway could also influence chromosome instability signatures. Weiler and colleagues showed that YAP and its binding partner TEAD4 could induce chromosome instability by interacting with FOXM1 [120]. After the inhibition of YAP, about four fifth gene of CIN25 and three fifth gene of CIN25 were reduced. Although it hasn't been clarified yet whether m6A modification is involved in affecting HCC progression by influencing chromosome instability. Several researchers have shown that YAP mRNA was m6A modified in HCC [121], colorectal cancer [122], NSCLC [123], and so on. Those results hint that m6A modification may implicated in HCC development through chromosome instability by influencing hepatic virus affection and some genes which need further investigation.

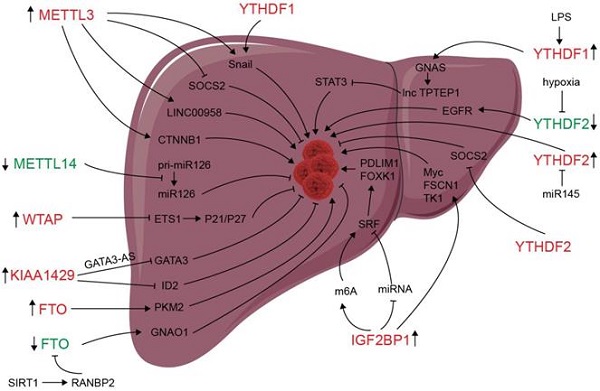

Figure 2Deregulation of m6A modifiers in liver cancers. Modifiers in red indicate an oncogenic role, modifiers in green indicate a tumor-suppressive role.

Angiogenesis is essential for HCC progression and metastasis. Vasculogenic mimicry (VM) formed by aggressive tumor cells has been found in various types of cancer, including ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma and HCC, and associated with poor prognosis in patients [124-126]. Pathologic angiogenesis is critical for the growth and malignant dissemination of solid tumors by providing oxygen, nutrients, and routes for metastasis [127]. Several studies demonstrated that m6A modification could also influence HCC progression through regulating angiogenesis. Qiao et al. showed that silencing METTL3 suppresses VM formation through inhibiting YAP1 expression [124]. Intratumoral hypoxia is a common signature of human solid cancer including HCC and could regulate the expression of genes that involver in regulating angiogenesis, EMT process, self-renewal of cancer stem cells, chemotherapy- and radiation- therapy resistance extracellular matrix remodeling, cancer stem cell maintenance through hypoxia-induced factor (HIF) [128]. Zhong et al. demonstrated that hypoxia down-regulated YTHDF2 expression, and forced YTHDF2 expression could suppress HCC carcinogenesis, proliferation and activation of MEK and ERK in HCC cells through directly binding the m6A sites on EGFR 3'UTR and subsequently promoting its degradation [129]. The activation of EGFR induced by EGF and TGF-α could induce the expression of VEGF which is a predominant stimulator of angiogenesis [130]. Those results illustrated that YTHDF2 may be involved in regulating HCC tumorigenesis by regulating angiogenesis through EGFR/VEGF signaling pathway. Hou et al. showed YTHDF2 expression was decreased in hypoxia and tumor tissues, and HIF-2α antagonist (PT2385) could restore YTHDF2 expression and inhibit HCC progression [131]. Mechanistically, YTHDF2 mediated the decay of m6A-modified interleukin 11 (IL11) and serpin family E member 2 (SERPINE2) mRNAs, which were involved in regulating the inflammation-mediated malignancy and disruption of vascular normalization. These studies showed that m6A modification might regulating HCC development by modulating neovascularization.

m6A modification and m6A regulators have been shown to be dysregulated in liver carcinoma, and m6A expression influences liver progression through proliferation, metastasis, inflammation, and vascularization (as showed in Figure 2). METTL3 facilitates migration, invasion and EMT of cancer cells by promoting Snail (a key transcription factor of EMT) expression through m6A-YTHDF1 pathway [56]. SUMOylation of METTL3 was positively associated with high metastasis potential of HCC via controlling Snail mRNA homeostasis in HCC [132]. Chen et al. showed that METTL3 promotes liver cancer progression by suppressing SOCS2 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 2) via m6A-YTHDF2-mediated degradation [55]. SOCS2 has been shown to inhibit proliferation, migration, and stemness in various cancers, including oral squamous carcinoma, leukemia, and HCC [54]. METTL3-mediated m6A modification upregulates LINC00958 expression, and subsequently enhances hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) expression by sponging miR-3619-5p, and consequently promotes HCC lipogenesis and progression [102]. METTL3 promoting HCC development by interacting with DGCR8 and promoting the maturation of miR-873-5p in an m6A-dependent manner, thereby inhibiting SMG1 expression [133]. METTL3 upregulation promotes hepatoblastoma (HB) progression through enhancing CTNNB1 mRNA stability and subsequently activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway [134]. WTAP suppresses ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1) in an m6A-HuR-dependent manner, which further reverses the inhibition of p21/p27 axis to promote G2/M phase of HCC cells, and consequently promotes HCC progression [83]. KIAA1429 upregulation facilitates migration and invasion of HCC by repressing ID2 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner [135]. lncRNA-GATA3-AS facilitates KIAA1429 induces m6A modification and degradation of GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3) pre-mRNA in an HuR-dependent manner, and consequently promotes HCC growth and metastasis [136]. Circ_KIAA1429 (has_circ_0084922) was upregulated and accelerate HCC development by facilitating HCC migration, invasion, and EMT process through enhancing Zeb1 mRNA stability in an m6A-YTHDF3 dependent manner [137]. However, METTL14 is downregulated in HCC, especially metastasis cancer, can interact with the microprocessor protein DGCR8 and promote pri-miR126 maturation in an m6A-dependent manner, and consequently suppresses HCC metastasis [3]. In summary, those results reveal that m6A “writers” complex involved in regulating HCC progression. However, the function of METTL14 and other m6A “writers” is apparently controversial. The reasons for the above conflicting findings might be associated with the heterogeneity of clinical samples. Further investigations are needed to settle these contradictory findings and clarify the role of different m6A “writer” in the progression of HCC.

Since its identification as the demethylase of m6A, FTO has been reported to play an important role in many cancers including liver cancer [138-141]. Li et al. reported a correlation between up-regulated FTO in liver cancer and poor prognosis. It was also shown that FTO mediates demethylation of PKM2 mRNA and promotes its translation to promote HCC progression [142]. Besides its oncogenic function, FTO also suppresses HCC progression. Liu et al. reported that SIRT1 activate RANBP2 that mediates FTO SUMOylation and degradation, and subsequently leads to m6A deposition in HCC tumor suppressor guanine nucleotide-binding protein G (o) subunit alpha (GNAO1) and inhibits its mRNA expression, and consequently results in liver cancer progression [139]. Recently, a study reveals that FTO plays a protective role in HCC development [143]. Hepatocyte-specific depletion of FTO not only impacts HCC initiation phase (increased tumor numbers) but also influences HCC development (increased numbers of larger tumors) by inhibiting Cul4a translation [143]. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common form of primary liver cancer. Rong et al. demonstrated that loss of FTO in ICC related to poor prognosis, mechanistically, FTO suppresses the anchorage-independent growth and mobility of ICC cells through demethylation and impairing oncogene TEAD2 mRNA stability [140]. These conflicting functions of FTO in HCC and ICC might be associated to heterogeneity of clinical samples and the context-specific m6A roles between HCC and ICC. ALKBH5 inhibits HCC cells proliferation and invasion by suppressing IGF2BP1-mediated LY6/PLAUR Domain Containing 1 (LYPD1) RNA stability [144].

The oncogenic or tumor suppressor role of m6A readers may be associated with their effect on transcripts processing. Several studies have indicated that chronic inflammation is involved in HCC progression [145]. Innate immune cell types, including macrophages, innate lymphoid cells, NK cells, Dendritic cells (DCs), and mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MALTs) are enriched in liver and play essential roles in liver homeostasis [146]. Traditionally, macrophages can be classified as M1 (pro-inflammatory), M2 (anti-inflammatory), or Mreg (immunosuppressive), and the balance of M1-M2 polarization involved in hepatic inflammation and repair [147]. It has been demonstrated that METTL3 facilitates M1 macrophage polarization via the methylation of STAT1 mRNA [148]. Ding et al. found that LPS used to stimulate the inflammatory response in HCC cells enhances GNAS expression in an m6A-YTHDF1-dependent manner [149]. Elevated G-protein alpha-subunit (GNAS) expression can promote inflammation-related HCC progression through promoting STAT3 activation by inhibiting lncRNA TPTEP1 interaction with STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3). YTHDF2 promotes the liver cancer stem cell phenotype and cancer metastasis by promoting OCT4 expression [150]. Hou and colleagues described that hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) inhibits YTHDF2 expression, resulting in elevated expression of m6A-containing interleukin 11 (IL11) and serpin family E member 2 (SERPINE2) mRNAs, which further leads to inflammation and vascular abnormalities in HCC [151]. YTHDF2, downregulated by hypoxia, can suppress HCC progression through binding m6A sites of EGFR 3'UTR and inducing its degradation, and consequently suppresses cell proliferation, tumor growth, and activation of MEK and ERK in HCC cells [129]. However, another research reported that YTHDF2 upregulated and exerts as an oncogene in HCC and can be inhibited by miR-145 [152]. ICF2BP1/2/3 protein were identified as m6A-binding proteins and plays an oncogenic role in HeLa (cervical cancer) and HepG2 (liver cancer) cells via enhancing the stability of MYC, FSCN1, and TK1 mRNAs [35]. IGF2BP1 promotes SRF expression in an m6A- and miRNA- dependent manner and subsequently promotes SRF downstream target gene including PDLIM7 and FOXK1 translation, consequently PDLIM7 and FOXK1 promote tumor cell growth and enhance cell invasion, and indicate a poor overall survival probability in liver, ovarian and lung cancer [153].

These studies illustrate a complicated role of m6A modification and m6A regulators in liver carcinogenesis. m6A modification and m6A regulators involve in regulating cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, immunity, vascular abnormalization, and EMT process. However, some of the studies have reported conflicting results on the expression and function of various m6A regulators. Most of MTCs upregulated and promote HCC progression, however, METTL14 is decreased and could suppressed liver cancer cell metastasis. The role of FTO and YTHDF2 are double-edged sword. When they down-regulated in carcinoma tissues, they may play a tumor suppressive role. However, if they up-regulated, they may be an oncogenic factor. The expression of FTO and YTHDF2 can be influenced by tumor heterogeneity, hypoxia, and post-translational modification. All the discrepant results of the above studies uncover a complicated role of m6A modification and m6A regulators in human HCC. Further investigation and effort will be required to reconcile these paradoxical results. Altered expression, function, and mechanism of m6A regulators in liver carcinoma are listed in Table 1.

Since m6A modification levels and m6A regulators play essential roles in regulating the progression of liver disease, targeting abnormal expressed m6A regulators may serve as a biomarker and potential therapeutic targets. Several studies showed that liver carcinogenesis is related to the altered expression of m6A regulators [3,129,135]. Bioinformation analysis in several studies reveal that METTL3 and YTHDF1 are both significantly upregulated and are associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients [53,154,155]. METTL3, VIRMA, and hnRNPC showed higher expression in tumor samples, while METTL14, ZC3H13, FTO, ALKBH5, YTHDF2, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2 showed higher expression in normal tissue samples [53,152,156,157]. High expression level of METTL14 is associated with a better prognosis in HCC patients [156]. YTHDF2 expression is closely associated with HCC malignance, and can be inhibited by miR-145 [152]. YTHDF2, YTHDF1, METTL3, KIAA1429, and ZC3H13 could be a prognostic signature of malignant HCC patients [52,157-159]. The expression of two genes (hnRNPA2B1 and RBM15) are closely related to the TNM stage and metastasis risk and can act as a prognostic indicator for HBV-related HCC patients in the early TNM stage [160]. In conclusion, METTL3, YTHDF1 are elevated and METTL14 is down-regulated in HCC and can be prognosis biomarker of HCC.

m6A levels in circulating tumor cells (CTCs) can be detected by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS). The authors showed that m6A modification levels in CTCs was significantly elevated compared to the whole blood cells and m6A levels in CTCs might be a non-invasive approach for cancer diagnosis [161]. Therefore, the altered expression of m6A regulators may be a biomarker for prognostic prediction in HCC patients.

Several studies demonstrated that dysregulation of m6A regulators associated with drug resistance. Taketo and colleagues showed that METTL3-depleted pancreatic cancer cells showed higher sensitivity to anticancer reagents such as 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, cisplatin and irradiation [162]. METTL3 knockdown in NSCLC inhibits tumor growth, metastasis and DDP resistance [163]. METTL3 induces the production of p53 R273H mutant protein that results in acquired multidrug resistance in colon cancer cells [164]. Elevated METTL3 expression is implicated in glioma stem-like cell maintenance and radioresistance [165]. The upregulation of FTO enhances chemo-radiotherapy resistance in cervical cancer [166]. Depletion of METTL3 under hypoxia significantly enhances sorafenib-resistant of HCC by decreasing the stability of FOXO3, and overexpression of FOXO3 restores m6A-dependent sorafenib sensitivity [167]. These results highlight the therapeutic value of targeting m6A modification and m6A regulators in drug-resistant tumors.

m6A regulators can be targeted by inhibitors. The nature product rhein is the first identified FTO inhibitor that exerts good inhibitory activity of FTO demethylation and led to increases of m6A modification levels [168,169]. However, it is not an FTO selective inhibitor, as it can also target ALKBH5 [170]. Entacapone, an FDA approved drug used to treat Parkinson's disease, has also be identified as FTO inhibitor that elicited the effects of FTO on gluconeogenesis in the liver and thermogenesis in adipose tissues in mice by acting on an FTO-FOXO1 regulatory axis [171]. Meclofenamic acid (MA), a non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drug, is to be identified as highly selective inhibitor of FTO [30]. Most recently, Su et al. reported two small-molecule inhibitors of FTO that can suppress leukemia stem/initiating cell maintenance and immune evasion by suppressing expression of immune checkpoint genes, especially LILRB4 [172]. Administration of PT2358, an antagonist HIF-2α, restores YTHDF2 expression which attenuates tumorous inflammation and angiogenesis, thus inhibiting HCC progression [151].

The m6A modification in liver can be influenced by gut microbiota, which can further alter lipid metabolism and insulin signaling [173]. Lu et al. reported that curcumin can affect METTL3, METTL14, ALKBH5, FTO, and YTHDF2 expression and subsequently increase m6A modification to inhibit LPS-induced liver injury and lipid metabolism disorders in piglets through inhibiting SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element binding proteins) and SCD-1 (stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1) expression in an m6A dependent manner [174]. Those studies reveal that altered m6A modification involved in regulating liver cancer cell metabolism, proliferation, invasion, and immunity, and is associated with clinical prognosis and progression, indicating that altered expression of m6A regulators may serve as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. However, more studies are required to determine the function of m6A modification on liver carcinogenesis and the potential as therapeutic targets.

Table 1Roles of m6A regulators in liver carcinoma

ProteinsCancerRoleFunctionMechanismReferenceMETTL3HCCOncogeneRegulating EMT progressionPromoting Snail expression[56, 132]HCCOncogenePromoting HCC cell proliferation and migrationRegulating SOCS2 expression[55]HCCOncogenePromoting HCC lipogenesis and progressionm6A modification enhances LINC00958 RNA stability and expression that sponged miR-3619-5p to upregulate HDGF expression[102]HCCOncogenePromoting the development of HCCPromoting the maturation of miR-873-5p and thereby inhibiting SMG1 expression[133]HBOncogenePromoting proliferation of HBRegulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation through regulating CTNNB1 expression[134]METTL14HCCSuppressorInhibiting the migration and invasivenessRegulating pre-miR-126 maturation through interacting with DGCR8[3]WTAPHCCOncogeneWTAP modulated the G2/M phase of HCC cellsSuppressing ETS1 expression in m6A-HuR dependent manner[83]KIAA1429HCCOncogeneEnhancing proliferation, migration, and invasion of HepG2 cellsInhibiting ID2 expression[135]HCCOncogenePromoting proliferation and metastasis of HCC cellsLeading to the degradation of GATA3 pre-mRNA[136]FTOHCCOncogenePromoting proliferation and in vivo tumor growthPromote PKM2 expression[142]HCCSuppressorSIRT1 activates RANBP2 that further mediates FTO SUMOylation and degradationDecreased FTO leads to hypo m6A modification of GNAO1 and reduced its RNA stability[139]HCCSuppressorFTO exerts protective role in the initiation of HCCInhibiting Cul4a translation[143]ICCSuppressorFTO suppresses the anchorage-independent growth and mobility of ICC cellsImpairing oncogene TEAD2 mRNA stability[140]ALKBH5HCCSuppressorALKBH5 inhibits the proliferationm6A is the most abundant internal modification which randomly exists on almost all types of RNAs, including mRNA, lncRNA, circRNA, miRNA, rRNA and snoRNA. Numerous studies have shown that m6A modification plays an essential role in physiological and pathological processes including cell differentiation, meiosis, sex determination, cancer progression, circadian rhythm, neuronal function, and chromatin state. m6A modification is induced by MTC consisting of METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, VIRMA, ZC3H13, HAKAI and RBM15/RBM15B, in which METTL3 is the only catalytic subunit. m6A in structural RNAs and U6 snRNAs can be methylated by METTL16, whereas METTL5 mediates m6A modification of 18 S rRNA and facilitates ZCCHC4 as the 28 S rRNA modification enzyme. m6Am modification is induced by PCIF1 and METTL4 mediates m6Am modification in internal U2 snRNAs. m6A deposition is removed by eraser proteins (FTO and ALKBH5). As the first identified m6A demethylase, FTO can not only demethylate internal m6A and cap m6Am but also mediates demethylation of m6A and m6Am in snRNAs and m1A in tRNAs.

In recent years, global m6A modification has been well described well in different disease contexts by using NGS. m6A deposition is not randomly distributed in transcripts but collectively deposited in 3'UTR and CDS regions, especially the stop codon. m6A deposition sites can be influenced by writers, erasers, histone modification, transcription factors, virus infection, chemical carcinogens, carRNAs, and environmental stimuli. The global m6A abundance can be detected by MeRIP-seq or m6A-seq. However, this approach has some limitations; it needs more initial RNA material; the m6A-antibody cross talks with m6Am and it cannot accurately position on m6A sites. Another technique uses m6A-sensitive RNA-endoribonuclease, which can cleave RNA at unmethylated ACA motifs and is used to detect m6A distribution (m6A-REF-seq or MAZTER-seq). However, this method is not useful for m6A sites in other sequence contexts. Mapping m6A sites precisely is a critical step for understanding its function and regulatory pathways. In this context, DART-seq has substantially improved the transcriptome-wide m6A level detection and provides an efficient detection method for limiting-amounts of RNA samples.

In many disease types, global m6A abundance, as well as m6A regulators, are altered. Because of the simultaneous alteration of m6A writers and erasers, the global m6A level changes may not be informative in carcinoma. Some investigators demonstrated that increased m6A modification in liver carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. However, other groups demonstrated that global m6A levels decrease in HCC tissues especially metastatic tumors. Therefore, the mechanism of m6A regulation in liver carcinoma progression needs further investigation. Recent studies also revealed that m6A modification affects ncRNAs processing such as maturation, cellular location, and function. Further investigations are required to understand the molecular details of these progresses affecting liver cancer progression.

m6A modification is a new layer of post-transcription regulation of gene expression. The dysregulated expression of m6A regulators involved in human carcinogenesis has been demonstrated in various cancer types, including HCC. Altered m6A regulators expression will influence target gene expression by modulating the mRNA stability and translation. m6A modification also plays an essential role in mediating cancer cells response to immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. However, the functional role of m6A in HCC are paradoxical, further studies are needed to illustrates the heterogeneity and complexity of m6A modification and m6A regulators in HCC carcinogenesis. Given the pivotal role of m6A modification and regulation in many cancers, targeting dysregulated m6A regulators may be a therapeutic option in cancer. Therefore, a better understanding of m6A may improve cancer therapy in the future.

m6A: N6-methyladenosine; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; Ψ: pseudouridine; m1A: N1-methyladenosine; m6Am: N6, 2-O-dimethyladenosine; ncRNAs: non-coding RNAs; CDS: coding sequences; 3'UTRs: 3'untranslated regions; MTC: m6A methylase complex; IGF2BPs: insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins); NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; HPLC-MS/MS: liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry; PA-m6A-seq: photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing strategy; m6A-CLIP-seq: UV cross-linked m6A antibody-bound RNA sample; a6A: N6-allyladenosine; hm6A: N6-hydroxymethyladenosine; dm6A: N6-dithiolsitolmethyladenosine; m7G: 7-methylguanosine; carRNAs: chromosome-associated regulatory RNAs; FMRP: fragile X mental retardation protein; CSC: cigarette smoke condensate; PM: particulate matter; HMPV: human metapneumovirus; dCas9: dead Case9; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; HFD: high-fat diet; T2D: Type 2 diabetes; Fasn: fatty acid synthase; PPARα: the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activator α; Scd1: stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; Acc1: acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1; HDGF: hepatoma-derived growth factor; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HB: hepatoblastoma; ETS1: ETS proto-oncogene 1; GATA3: 3′ UTR of GATA binding protein 3; GNAO1: guanine nucleotide-binding protein G (o) subunit alpha; ICC: Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma; DCs: dendritic cells; MALTs: mucosal-associated invariant T cells; GNAS: G-protein alpha-subunit; HIF-2α: hypoxia-inducible factor-2α; IL11: Interleukin 11; SERPINE2: serpin family E member 2; CTCs: circulating tumor cells; LC-ESI-MS/MS: liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry; MA: Meclofenamic acid; SREBP-1c: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c; SCD-1: stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1.

Authors' contributionsX.Y.P conceived and wrote the manuscript. C. H and J.L. conceived and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis project was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (82070628, U19A2001), Anhui Provincial Universities Natural Science Foundation (KJ2019A0233), and The University Synergy Innovation Program of An hui Province (GXXT-2019-045). We apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited owing to space constraints.

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

1. Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187-200

2. Haussmann IU, Bodi Z, Sanchez-Moran E, Mongan NP, Archer N, Fray RG. et al. m(6)A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature. 2016;540:301-4

3. Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, Liu F, Yuan JH, Wang F. et al. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N(6) -methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65:529-43

4. Han J, Wang JZ, Yang X, Yu H, Zhou R, Lu HC. et al. METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:110

5. Nesterova TB, Wei G, Coker H, Pintacuda G, Bowness JS, Zhang T. et al. Systematic allelic analysis defines the interplay of key pathways in X chromosome inactivation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3129

6. Yang D, Qiao J, Wang G, Lan Y, Li G, Guo X. et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:3906-20

7. Tatomer DC, Wilusz JE. An Unchartered Journey for Ribosomes: Circumnavigating Circular RNAs to Produce Proteins. Mol Cell. 2017;66:1-2

8. Zhou C, Molinie B, Daneshvar K, Pondick JV, Wang J, Van Wittenberghe N. et al. Genome-Wide Maps of m6A circRNAs Identify Widespread and Cell-Type-Specific Methylation Patterns that Are Distinct from mRNAs. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2262-76

9. Ma H, Wang X, Cai J, Dai Q, Natchiar SK, Lv R. et al. N(6-)Methyladenosine methyltransferase ZCCHC4 mediates ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:88-94

10. Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, Lenz C, Urlaub H, Hobartner C. et al. Human METTL16 is a N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:2004-14

11. Mendel M, Chen KM, Homolka D, Gos P, Pandey RR, McCarthy AA. et al. Methylation of Structured RNA by the m(6)A Writer METTL16 Is Essential for Mouse Embryonic Development. Mol Cell. 2018;71:986-1000 e11

12. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ. et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18-29

13. Aguilo F, Zhang F, Sancho A, Fidalgo M, Di Cecilia S, Vashisht A. et al. Coordination of m(6)A mRNA Methylation and Gene Transcription by ZFP217 Regulates Pluripotency and Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:689-704

14. Alarcon CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell. 2015;162:1299-308

15. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H. et al. N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388-99

16. Du H, Zhao Y, He J, Zhang Y, Xi H, Liu M. et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12626

17. Clancy MJ, Shambaugh ME, Timpte CS, Bokar JA. Induction of sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to the formation of N6-methyladenosine in mRNA: a potential mechanism for the activity of the IME4 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4509-18

18. Schwartz S, Agarwala SD, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Mertins P, Shishkin A. et al. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155:1409-21

19. Luo GZ, MacQueen A, Zheng G, Duan H, Dore LC, Lu Z. et al. Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5630

20. Lence T, Akhtar J, Bayer M, Schmid K, Spindler L, Ho CH. et al. m(6)A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature. 2016;540:242-7

21. Kan L, Grozhik AV, Vedanayagam J, Patil DP, Pang N, Lim KS. et al. The m(6)A pathway facilitates sex determination in Drosophila. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15737

22. Rottman FM, Desrosiers RC, Friderici K. Nucleotide methylation patterns in eukaryotic mRNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1976;19:21-38

23. Schibler U, Kelley DE, Perry RP. Comparison of methylated sequences in messenger RNA and heterogeneous nuclear RNA from mouse L cells. J Mol Biol. 1977;115:6

留言 (0)