The Arab region, consisting of 22 countries and a population of approximately 425 million, has one of the largest youth demographics globally, with 60% of its population under the age of 25 (4). Mental health disorders are a critical concern in this region (1), with their burden, measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), exceeding the global average in many Arab countries (2). Arab Adolescents are particularly at risk due to their heightened exposure to social, political, and economic stressors (1, 3). Among this demographic, depression is projected to be the most prevalent mental health disorder (5, 6).

Jordan, as part of the Arab region, exemplifies this challenge, with a national study reporting a 34% prevalence rate of moderate to severe depression among adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Of these, 19% experience moderate symptoms, and 15% face severe symptoms (7). Depression severity was notably higher among female adolescents aged 14–17 years, those from families with lower monthly incomes, and individuals with chronic medical or mental health conditions (7). Despite the evident need for mental health interventions, Jordan, like many Arab countries, faces a critical shortage of mental health resources. Screening, treatment, and prevention practices for depression remain far below recommended standards. Mental health services are primarily limited to two psychiatric hospitals, a few psychiatric units in general hospitals, and outpatient clinics, where the focus is predominantly on psychopharmacological treatments. Psychotherapy services are underdeveloped, with minimal availability for families of individuals with depression (3). Furthermore, while Jordan has committed to integrating mental health services into its primary health care system, progress toward implementation has been minimal (1, 3). These systemic challenges are further exacerbated by a significant shortage of trained mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, psychologists, and psychiatric nurses, as well as pervasive stigma surrounding mental health issues, which discourages individuals from seeking care (8–12). Addressing these barriers necessitates scalable, culturally appropriate, and innovative strategies to enhance mental health care access and outcomes.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (13), addressing the barriers faced by underserved populations is essential for improving global health equity. These barriers can be mitigated through low-intensity interventions, which are designed to be resource-efficient and accessible to a large number of individuals. Examples include self-help programs and interventions delivered by non-professionals (14–17). Among such approaches, digital health interventions (DHIs) have emerged as promising tools due to their ability to provide anonymity, flexibility in time and location, accessibility, and scalability. These characteristics make DHIs particularly suited to overcoming structural barriers to healthcare access (18–21). Evidence has demonstrated the effectiveness of DHIs in preventing and treating mental health disorders (22–26). However, most DHIs have been developed and tested primarily in high-income countries for majority populations. Their effectiveness is often reduced when applied to individuals from diverse cultural or ethnic backgrounds, who face additional barriers such as language, cultural differences in understanding disease and treatment, or limited knowledge of the healthcare system (17, 27–31). These challenges highlight the importance of incorporating cultural considerations into intervention development to address the unique needs of different populations (32). While creating entirely new interventions for each cultural context requires substantial resources, an alternative approach is to adapt existing evidence-based psychological treatments to align with the cultural context of the target population (33).

CATCH-IT (Competent Adulthood Transition with Cognitive Humanistic and Interpersonal Training) is an internet-based depression prevention program designed to help adolescents build resilience and prevent depression. It integrates components of behavioral activation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and interpersonal therapy. The program was developed to target adolescents with sub-threshold depressive symptoms and provide an acceptable, low-cost, and broadly available intervention/prevention model of depressive disorders (34). In addition, its techniques have been shown to impact a range of emotional and psychological issues, including anxiety, self-harm risk, and emotional resilience (35, 36). The program is based on the understanding that a large majority of individuals experience sub-threshold depressive symptoms, which do not currently meet the criteria for major depressive disorder but often progress to it over time (37, 38). Sub-threshold depressive symptoms, such as minor depression (defined as two symptoms persisting for more than one week), are associated with significant costs and impairments in social and academic functioning (39, 40). Consequently, early or preventive interventions targeting individuals with sub-threshold symptoms have been consistently recommended to reduce the overall burden of depressive disorders (41, 42).

Early studies of the program have demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing depressive symptoms, with improvements observed over multiple timeframes, including 6, 12, and 30 months (43–45). For example, Van Voorhees et al. conducted a randomized clinical trial within primary care settings and found that adolescents who participated in CATCH-IT had significantly reduced depressive symptoms over the 12-week intervention period (43). This initial success was further supported by longer-term studies, such as Saulsberry et al. (45), which reported positive outcomes at the one-year mark for preventing adolescent depression in primary care settings, and Richards et al. (44), who found sustained improvements in depressive symptoms up to 2.5 years post-intervention. These findings were corroborated by Gladstone et al., who compared CATCH-IT to an internet-based general health education program. They demonstrated that CATCH-IT participants with elevated symptoms of depression at baseline reported fewer episodes of depression at follow-up, reinforcing its effectiveness in addressing mental health concerns among adolescents (46). Another study found that adolescents with sub-threshold depressed mood showed a clear preference for innovative behavioral treatment approaches, such as CATCH-IT, for depression prevention (47). International studies have also expanded the reach of CATCH-IT, supporting its utility across diverse cultural contexts. For instance, a study by Sobowale et al. (48) adapted the program for Chinese adolescents, and it was later piloted, showing that the culturally adapted version significantly reduced depression and anxiety symptoms among this group (49).

Despite its promise and public health relevance, CATCH-IT and similar DHIs have not been tested in the Arab region, leaving a critical gap in understanding their effectiveness within this cultural context. A study by Al Dweik et al. (50) systematically reviewed DHIs for mental health in the Arab region, examining their opportunities and challenges. The study highlighted the diverse modalities and platforms used to address various mental health conditions and emphasized the potential of digital tools to enhance access to care and reduce stigma. However, it also underscored significant gaps, such as limited cultural tailoring of interventions, lack of integration with broader mental health systems, and insufficient evidence on long-term outcomes. The findings point to the urgent need for more culturally sensitive, scalable, and comprehensive DHIs to address mental health challenges effectively in the region.

These recommendations are particularly relevant given the remarkable growth in internet penetration across the Arab region over the past decade, driven by advancements in digital infrastructure, increased smartphone affordability, and widespread adoption of social media platforms (51, 52). As of 2023, internet engagement in the Arab region slightly exceeded the global average internet penetration rate of approximately 64.5% (51, 52). In Jordan specifically, adolescents rank among the highest internet users in the region (53), with activities such as social media, online gaming, and instant messaging forming integral parts of their daily lives. A recent report indicated that 97.1% of males and 95.8% of females aged 15–19 have internet access in Jordan (54).

The current studyThe widespread of internet usage among adolescents in Jordan presents a significant opportunity to implement DHIs targeting mental health issues such as depression. Therefore, this research thrived in its mission to explore the potential of culturally adapted digital interventions for addressing mental health challenges among Jordanian adolescents. With a focus on scalability and cultural alignment, this initiative represents a pioneering effort to provide innovative and accessible solutions for underserved youth populations in the country. This research is grounded in findings from meta-analyses that highlight the importance of cultural adaptation, suggesting that treatments tailored to populations for whom the intervention was not originally designed are significantly more effective than non-adapted versions (55, 56).

This research has also addressed factors that need consideration when introducing new interventions, including the motivational and behavioral predictors that influence adolescents’ engagement. Research has shown that organizing factors according to the Theory of Planned Behavior framework can effectively predict adolescents’ and young adults’ perceived need for treatment and their intention to accept a physician’s diagnosis of major depression (57, 58). This theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the factors that drive motivation, intention, and adherence to behaviors. In this model, intention is considered the most immediate precursor to behavior and is influenced by three key components: attitudes and beliefs regarding the behavior (e.g., attitudes toward an intervention), subjective norms (e.g., the influence of family, peers, or employers), and perceived behavioral control (e.g., self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s ability to perform the behavior) (59). For example, in the context of adhering to a depression intervention, intention is shaped by how individuals perceive the effectiveness and importance of the intervention, the social pressures they feel from their environment, and their confidence in their ability to follow through. Understanding the attitudinal predictors of motivation and adherence is crucial for mental health care providers, health policy planners, and prevention researchers, particularly when designing interventions that seek to enhance motivation and adherence to preventive care or digital health interventions.

Study aims and hypothesesPrimary aim 1: Evaluate the feasibility and cultural acceptability of Al-Khaizuran DHI among Jordanian adolescents, and compare its acceptability to targeted school-based group CBT. We hypothesize that Al-Khaizuran DHI will be feasible, culturally acceptable, and demonstrate higher engagement and more favorable acceptability ratings than school-based group CBT

Primary aim 2: Evaluate the comparative effectiveness of Al-Khaizuran and school-based group CBT in preventing the onset of depressive episodes and improving other patient-centered outcomes (depressive symptoms, resiliency, and intervention attitudes and preferences) among Jordanian adolescents. We hypothesize that both Al-Khaizuran and school-based group CBT will be comparably effective in preventing depressive episodes and improving other patient-centered outcomes.

Secondary aim 1: To explore the role of adolescents’ attitudes and beliefs regarding the intervention’s effectiveness as predictors of their intention to adopt preventive behaviors and engage in behavioral changes. We hypothesize that these attitudes and beliefs will be strong predictors of their intention to make behavioral changes and engage in preventive strategies.

Guiding frameworksTwo frameworks were employed to guide the content and procedural components of the cultural adaptation of the CATCH-IT program for Jordanian adolescents. The first was the Ecological Validity Framework by Bernal et al. (60), which informed the adaptation of intervention components across eight key domains: language (translation and regional or subcultural differences), persons (roles and patient–therapist relationships), metaphors (symbols and sayings), content (values, customs, and traditions), concepts (theoretical model of the treatment), goals (alignment between therapist and patient objectives), methods (procedures for achieving treatment goals), and context (broader social, economic, and political environments). The second framework, Barrera and Castro’s Heuristic Framework for the Cultural Adaptation of Interventions (61), guided procedural adaptations. This model outlines four steps: (1) gathering information through literature reviews or qualitative research, (2) developing a preliminary adaptation based on the information collected, (3) testing the preliminary adaptation through pilot or case studies, and (4) refining the adaptation based on findings from these studies. Below is a detailed description of how the two frameworks were used to guide the study.

The Al-Khaizuran project: a phased approach to developing a culturally adapted digital intervention for Jordanian adolescentsAl-Khaizuran, meaning “Bamboo” in English, was chosen as the adaptation project’s name to symbolize the remarkable resilience of bamboo, a plant known for its rapid growth, ability to thrive in diverse environments, and flexibility that allows it to bend without breaking even in strong winds or heavy rains.

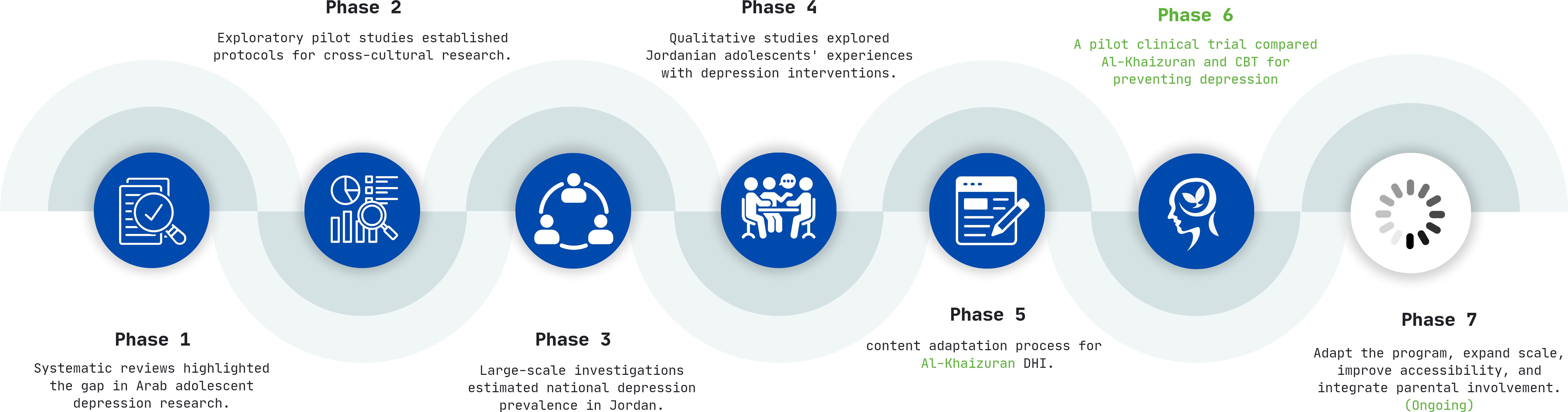

Procedural adaptation (phases 1-4, 6-7)Based on the aforementioned theoretical frameworks, a systematic and comprehensive scientific approach was adopted to ensure that the intervention was evidence-based, culturally relevant, and tailored to the specific needs of the target population. This process followed seven distinct phases for intervention development. Phase one included systematic reviews that explored the mental health profile of Arab adolescents, particularly depression. This work highlighted a significant gap in the literature in terms of availability of prevalence data and culturally competent tools and interventions, which made it difficult to design, implement, and disseminate effective programs to restore, maintain and promote the mental health of Arab adolescents (3, 10). Building on these results, phase two included a series of exploratory pilot studies establishing an evidence-based protocol for conducting cross-cultural research in Jordan, as an Arabic country exemplar, taking into consideration all ethical, methodological, cultural, linguistic, and logistical issues that might potentially affect the validity and reliability of collected data (62, 63). In phase three, the work moved to large-scale investigation that aimed at estimating the national prevalence of depression among adolescents in Jordan (7). This work also identified characteristics associated with the prevalence and severity of these problems, including sociodemographic and health characteristics (8, 64, 65). National data were also utilized to compare and contrast available depression assessment tools often utilized in the Arab context and introduce the most appropriate factor structure for this population (66). Phase four encompassed qualitative studies centered on Jordanian adolescents suffering from depression, aiming to capture their experiences and dysfunctional attitudes toward various depression interventions. During these studies, the translated and adapted concept and methodology were presented to the participants. Their comprehensive feedback, including both positive and negative aspects, was meticulously analyzed and incorporated to enhance and develop the intervention strategies (67, 68). Phase 5 included the content adaptation process detailed in the next section. Phase six, which is presented in this paper, includes a mixed methods randomized clinical trial described in details in next sections. Phase seven of the project is currently underway, involving modifications based on phase 6. During this phase, we are refining the program based on the insights gathered and preparing for its broader implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Al-Khaizuran DHI development phases.

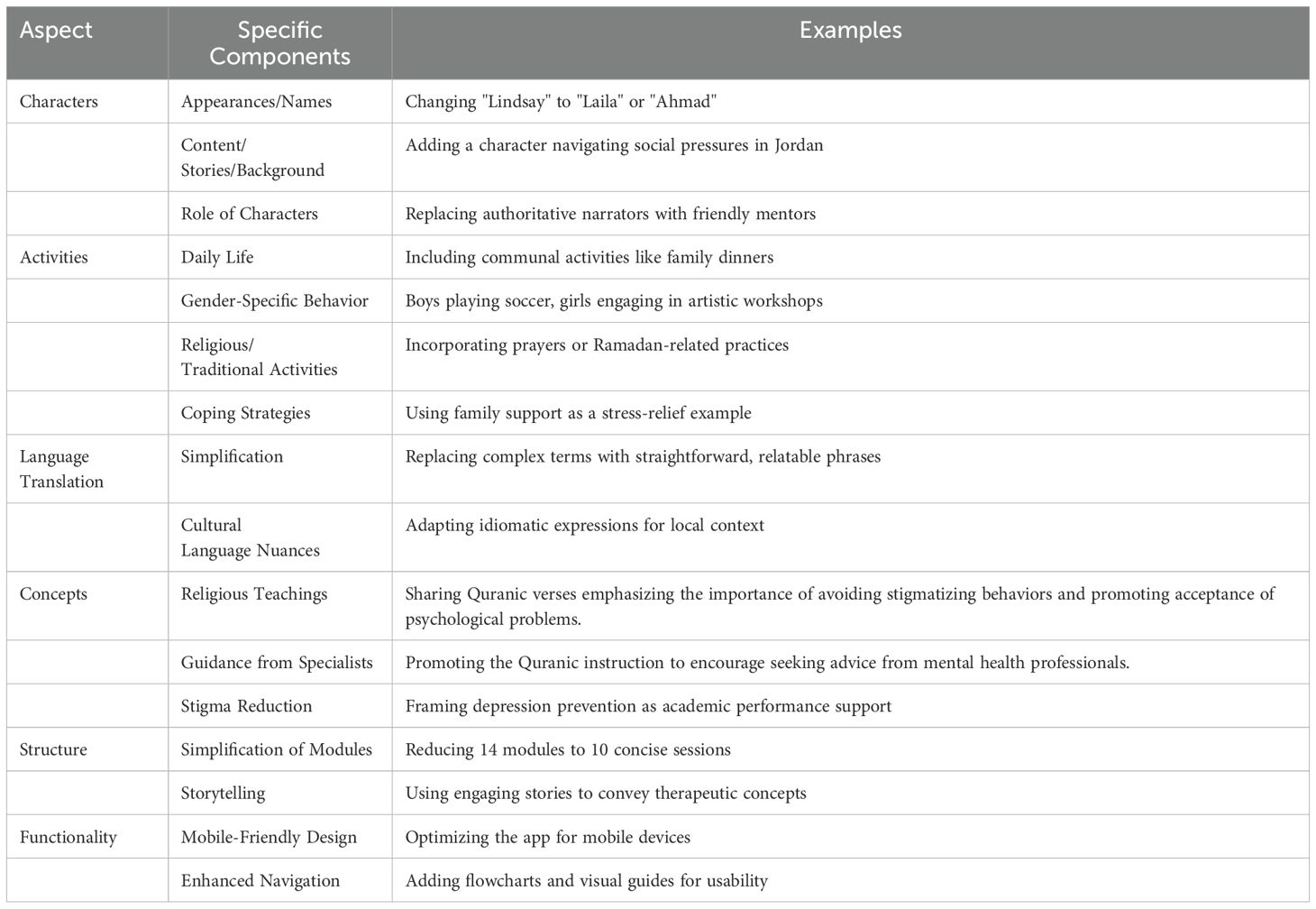

Content adaptation (phase 5)The content adaptation process for Al-Khaizuran focused on six key aspects to ensure cultural relevance and usability for Jordanian adolescents. These aspects included characters, activities, language translation, concepts of mental health and treatment, structure, and functionality, each adapted to align with the cultural and contextual needs of the target population (32, 69). See Table 1.

Table 1. The content adaptation process for Al-Khaizuran.

The first aspect, characters, involved significant changes to ensure relatability. The names of the characters were adapted to resonate with local culture, replacing Western names such as “Lindsay” with culturally relevant names like “Laila” or “Ahmad.” Additionally, new character backgrounds were introduced, such as a young girl navigating social pressures in Jordan, reflecting the lived experiences of adolescents in the region. The roles of narrators were also modified, shifting from authoritative figures to more conversational and approachable styles, akin to a friendly elder or mentor sharing advice, rather than an expert lecturing.

Activities were another focal point of adaptation. Daily life activities were redesigned to prioritize communal and family-oriented practices, such as group games or community events, over solitary tasks. Gender-separated activities were included, such as boys playing soccer and girls engaging in artistic workshops, to align with societal norms. Exercises incorporating religious and traditional practices, like prayer or storytelling around religious occasions, were added to enhance cultural relevance. Moreover, coping strategies were tailored to local contexts, incorporating examples like seeking guidance from a trusted elder or connecting with extended family for support.

For language translation, the text was simplified to ensure easier comprehension, removing overly technical terms and adapting to the reading level of adolescents. Cultural language nuances were also addressed by replacing metaphors and idiomatic expressions with phrases more familiar to the Jordanian audience, ensuring the intervention felt accessible and relatable.

The concepts of mental health and treatment were framed in culturally sensitive ways. Mental health was often explained through regular symptoms like fatigue or lack of energy, which are commonly recognized expressions of distress in the region. To reduce stigma, the intervention positioned depression prevention as a tool for stress management or academic performance enhancement, making the subject matter more approachable and less stigmatized. The Islamic religious context of participants was utilized as an enabler. Islamic teachings emphasize the importance of seeking treatment and discourage harmful labeling or mocking of others. For instance, a verse from the Holy Quran states: “Let not some men among you laugh at others, it may be that the latter are better than the former. Nor let some women laugh at others, it may be that the latter are better than the former. Nor defame nor be sarcastic to each other, nor call each other by offensive nicknames … And those who do not desist are indeed doing wrong.” (Al-Hujuraat: 11). This verse highlights the prohibition of behaviors that foster hatred or disrupt societal harmony, stressing that actions like mocking or name-calling are sinful and require sincere repentance (Taubah). These principles extend to interactions with individuals experiencing mental illnesses, as Islam categorically rejects stigmatizing beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Additionally, another verse advises: “If ye realize this not, ask of those who possess the Message.” (Al-Nahl: 43). This underscores the importance of consulting specialists in fields where one lacks knowledge, including mental health, rather than relying on unscientific or traditional approaches. Integrating these aspects into mental health interventions has been found promising (10).

The program’s structure underwent significant adjustments. The original 14 modules were condensed into 10 shorter, focused sessions to maintain participant engagement while retaining the therapeutic value of the content. Dense academic descriptions were replaced with engaging storytelling to make the material more relatable and appealing for young participants.

Finally, functionality was adapted to align with the technological habits of the target population. Recognizing the widespread use of smartphones among Jordanian adolescents, the program was optimized for mobile accessibility rather than a website. Navigation was enhanced with visual aids, including tables and flowcharts, to simplify the user experience and ensure the app was easy to use. These adaptations collectively aimed at producing Al-Khaizuran as both culturally relevant and user-friendly, increasing its potential to effectively support mental health among Jordanian adolescents. Fidelity checks were conducted throughout the adaptation process to ensure that the main therapeutic components of CATCH-IT, including behavioral activation, CBT, and interpersonal therapy, were preserved. These checks involved regular reviews by clinical experts to ensure that the adapted modules remained aligned with the evidence-based foundations of CATCH-IT, while also being culturally appropriate for Jordanian adolescents.

Mixed methodologyRCT designA two-arm, single-blind, individually randomized treatment trial was conducted. Participants were assigned to either Al-Khaizuran DHI or school-based group CBT. Outcomes for clinical effectiveness were assessed at baseline and postintervention. This study was prospectively registered on the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN14751844) and received local ethical approval from the University of Jordan (number: 19.2018.1106) and the Jordanian Ministry of Education (number: 3.10.22420). The study was conducted in the two largest governorates in Jordan, Amman and Zarqa, and involved two large public schools that enroll students from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. All participating students were already enrolled in these schools with the intervention designed to integrate seamlessly within the school environment, ensuring accessibility and ease of participation for all students.

Qualitative interviews designTo support or clarify the quantitative results gathered by the study questionnaire, we conducted a series of semi-structured phone interviews with eight participants, consisting of an equal number of males and females. Each interview lasted approximately 20 minutes and aimed to explore the students’ experiences and perceptions of the program. The interviews were designed to capture in-depth insights into how the program influenced the participants, focusing on their engagement, the perceived benefits, and any challenges they encountered during their participation. To ensure a diverse range of perspectives on the intervention, participants were selected based on their engagement with the program, categorized into three groups according to the percentage of modules they completed: High engagement: Participants who completed 75–100% of the modules (n=3); Moderate engagement: Participants who completed 40–74% of the modules (n=3); and Low engagement: Participants who completed 0–39% of the modules (n=2).

The qualitative interview guide for evaluating the website is structured into four key sections: (1) Usage and Engagement: explores interaction patterns, with questions like, “How often do you visit the website?” and “What features or sections of the website do you use most frequently?”, (2) Effectiveness and Impact: assesses the site’s influence on mental health, with questions such as, “Has using the website helped you manage or reduce symptoms of depression?” and “Can you provide specific examples of how the website has been beneficial to you?” (3) The Usability and Design: focuses on ease of navigation and user interface, asking questions like, “How easy is it to navigate the website?” and “Have you encountered any technical issues or bugs while using the website?”, and (4) Suggestions for Improvement: invites feedback for enhancements, with prompts like, “What do you like least about the website?” and “What would it be if you could change one thing about the website?”.

Inclusion criteriaEligible participants consisted of male and female school adolescents aged 13-17 years who exhibited mild to moderate depression (scores ranging between 35 and 49 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II). Individuals with severe depression scores were not included in the study. This is primarily because CATCH-IT program is designed as a preventive intervention aimed at adolescents experiencing subthreshold depressive symptoms, not those with severe symptoms or current major depressive disorder. Additionally, adolescents with comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder, thought disorders, conduct disorders, or substance use disorders, were excluded since these conditions require different or additional treatments. Adolescents presenting with severe suicidality at baseline (based on the Suicide Intent Scale and the Suicide Ideation Scale) were also excluded. Instead, specific procedures were implemented to refer these cases for urgent care, as detailed in the ethical considerations section. Furthermore, adolescents already receiving other forms of depression treatment outside of the study were excluded to prevent contamination of the study results.

Power analysisThe required sample size for this study was calculated based on a statistical test of difference between two independent means (groups). The effect size was estimated as medium based on previous evaluations of the CATCH-IT program (35, 36, 44–46, 49, 69). Using a significance level of 0.05, with a power level of 0.8, a minimum sample size of 106 participants was required. A retrospective power analysis was conducted to determine if the study had sufficient power to detect meaningful differences between the intervention groups. The observed mean difference between groups, the pooled standard deviation, the sample sizes of each group, and the significance level (α=0.05) were used to calculate the statistical power of the study. The power calculation was then performed using a two-sample t-test for independent groups, assuming a two-tailed test. Results indicated that the sample size provided sufficient power to detect medium to large effect sizes, which aligns with the anticipated impact based on prior evaluations of similar interventions. However, the power to detect smaller effect sizes may have been limited due to the sample size constraints of this study.

Recruitment and consentingParents were invited to participate through SMS messages sent by the school principals, as this is the customary method of communication between school administrators and parents. Participation was voluntary, and parents who agreed to participate responded to the invitation by confirming their willingness. Boys and girls whose parents consented to their participation received a comprehensive package containing all study details. This package provided clear and thorough information about the study’s objectives, procedures, and expectations to ensure informed participation. Those who agreed to participate were invited to a meeting with the study Principal Investigator. During this meeting, the procedures were explained in detail once again, ensuring that both participants and their parents fully understood the study. Any questions or concerns were addressed comprehensively. After this thorough discussion, written assents from the adolescents were collected.

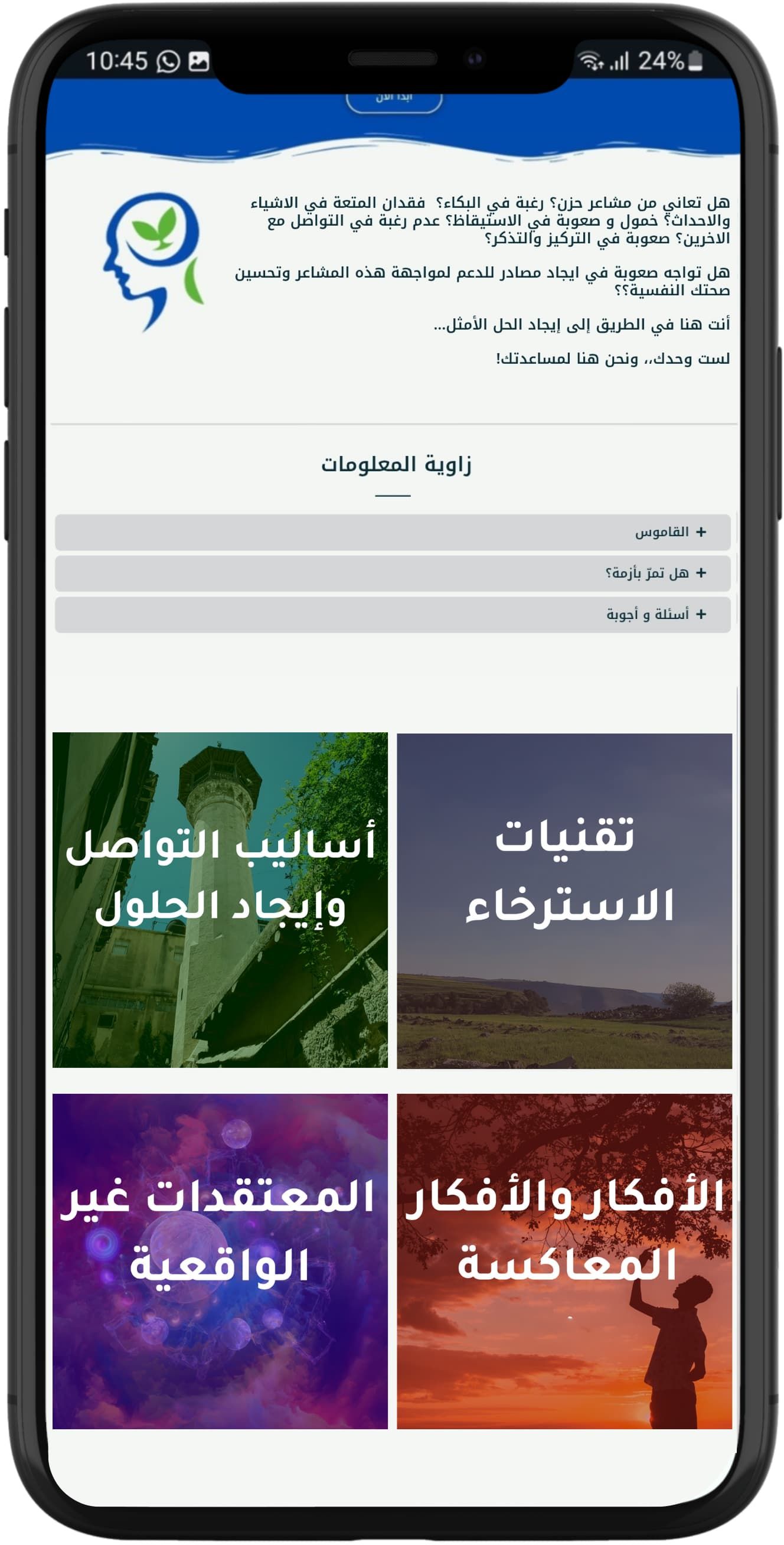

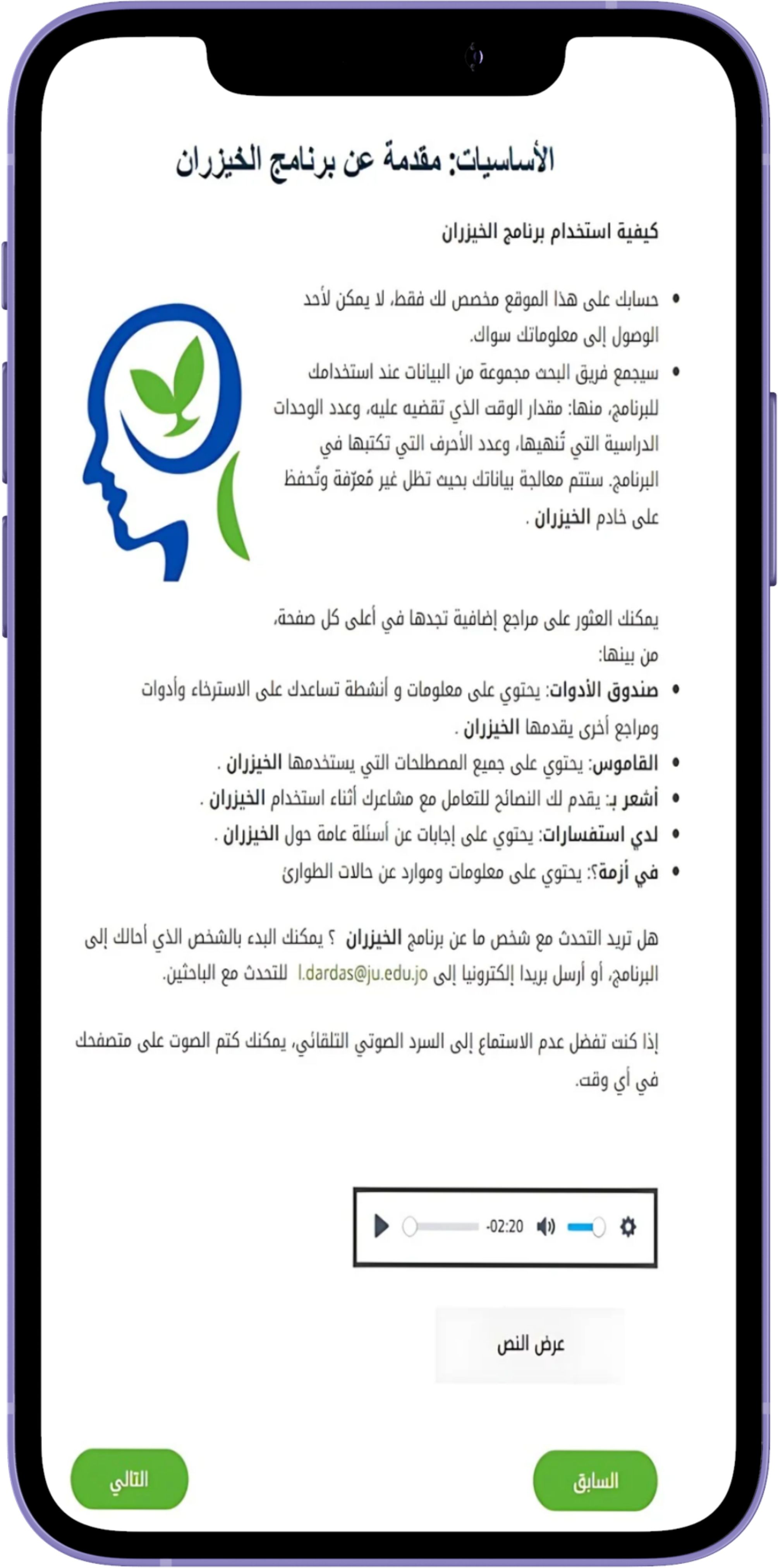

Al-Khaizuran Digital Health InterventionAl-Khaizuran DHI is a self-paced, 10-module digital program designed to help Jordanian adolescents manage depression symptoms, prevent depressive disorders, and build resilience. The modules are concise and user-friendly, allowing participants to progress at their own speed, accommodating individual schedules and learning preferences. Completion time varies based on personal engagement and pacing. The modules generally follow a consistent structure to facilitate learning and engagement. They begin with an introduction to key concepts, followed by a recap of the previous module and a warm-up exercise to reinforce learning. See Supplementary Table S1 for the modules content. The main content also includes questions, examples, and discussions, complemented by real-life stories that demonstrate the skills being taught. The modules also include real-life stories that demonstrate the application of the skills taught, making the content relatable. Users then complete exercises, known as Skill Builders, which allow them to apply what they have learned to their own lives. Feedback sections invite users to reflect on the module, while the Wrap-Up recaps the main points and sets the stage for the next module. Additionally, users are encouraged to set new goals and engage in self-training exercises, with a reward system featuring fun activities and a bulletin board for personal interaction, further fostering a sense of community. See Figures 2–6 of the DHI pages.

Figure 2. Al-Khaizuran DHI homepage displaying the website's module titles, along with the Frequently Asked Questions section and glossary.

Figure 3. Al-Khaizuran DHI content guide providing detailed instructions on how to navigate the website.

Figure 4. Al-Khaizuran DHI character adaptation.

Figure 5. Sample of Al-Khaizuran DHI exercises supported with audiovisuals. The content focuses on how to identify automatic negative thoughts.

Figure 6. Sample of Al-Khaizuran DHI interactive exercises focused on solving social conflicts.

The control: school-based group CBTThis school-based group therapy program consisted of eight structured sessions aimed at providing CBT interventions. We used the Coping with Depression: Adolescent Course, which was the foundation for the CBT sections of the CATCH-IT materials (43). The aim was to compare a DHI with a group-based model, both of which are based on the same source manual. The program was designed to address symptoms of depression, anxiety, and general distress through a combination of psychoeducation, mood assessments, and behavioral exercises. Each session builds upon previous ones, progressively equipping participants with skills such as recognizing negative thought patterns, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and problem-solving techniques. The program emphasizes both self-monitoring and practical application of CBT strategies, with a focus on fostering long-term emotional regulation and preventing relapse. Participants were given homework assignments after each session to reinforce the techniques learned, enhancing both individual engagement and therapeutic outcomes. The group sessions were facilitated by a certified educational psychologist who had received specialized training in delivering the training course materials. These sessions were held in designated activity rooms within the same schools, offering a familiar and supportive environment for participants. To ensure the quality and consistency of the intervention, fidelity checks were performed by the leading author to monitor the psychologist’s adherence to the program’s protocols. See Supplementary Table S2 for the sessions content.

RandomizationThe random allocation sequence was generated using Qualtrics software and integrated into the baseline questionnaire. An independent research coordinator, not involved in the intervention delivery or outcome assessment, enrolled the participants by verifying their eligibility and ensuring completion of the baseline assessment. Once the assessment was completed, Qualtrics automatically assigned participants to either the Al-Khaizuran group or the group CBT group in a 1:1 ratio. See Supplementary Figure S1.

MeasuresThe Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (70) was used to evaluate the presence and intensity of depressive symptoms in participants. The validated Arabic version (63) comprises 21 items, each offering four self-assessment statements covering a two-week period, with scores ranging from 1 to 4. The total depression score, which ranges from 21 to 84, is calculated by summing the responses across all items, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. Based on the total scores, each adolescent’s level of depression is categorized into four distinct ranges: (1) minimal (21 to 34), (2) mild (35 to 40), (3) moderate (41 to 49), and (4) severe (50 to 84). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was.92.

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-Short Form (CD-RISC-10) (71) was used to assess resilience, including personal competence, tenacity, tolerance to negative affect, strengthening effects of stress, positive acceptance of change, secure relationships, control, and spiritual influences. The scale comprises 10 items selected from the original 25-item CD-RISC-25. Respondents’ scores can range from 0 to 40, with responses rated as: 0 = Not true at all, 1 = Rarely true, 2 = Sometimes true, 3 = Often true, and 4 = True nearly all the time. The scale demonstrated good reliability, with α = .81 and ω = .82 (72). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was.88.

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale-Shortened Version (DAS-SV) (73) was used to measure maladaptive cognitive patterns associated with psychopathology, such as those outlined in Beck’s cognitive theory. This scale includes items designed to capture underlying assumptions and beliefs that, when combined with stressors, could lead to clinical symptoms (74, 75). Derived from a factor analysis of the original 100-item DAS (76), it uses a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The items reflect rigid and absolute thinking patterns using terms like “always,” “never,” and “must.”

The Preferences for Intervention Scale (77) was used to measure individual preferences for different psychological intervention modalities. The scale includes 16 items that assess participants’ comfort and willingness to engage in various treatment options, such as natural recovery, medication, one-on-one counseling, or group counseling. Participants rated statements, including “I will wait and get over it naturally” and “Use anti-depressant drugs,” on a Likert scale from 1 (definitely acceptable) to 4 (definitely not acceptable). Additional options included consulting a primary care physician or completing a questionnaire online. All items followed the same rating scale as the original (47). This scale is particularly relevant for understanding patient engagement and acceptance of the intervention.

The Behavioral Intention Scale (78) was used to assess participants’ intentions to change their approach to solving everyday problems to mitigate depression risk. The scale includes statements reflecting various stages of consideration and decision-making, such as “I have not given any thought to changing…” and “I have decided to change … and I have a plan.” Participants select the statement that best describes their current position, with higher scores indicating stronger commitment to behavioral change.

The Attitudes Toward Depression Prevention Scale (ATDPS) (44) was utilized to assess participants’ beliefs and dysfunctional attitudes toward depression prevention strategies, such as lifestyle modifications, early intervention, and educational initiatives. This scale consists of multiple items designed to evaluate how participants perceive the significance and effectiveness of these strategies, as well as their readiness to engage in preventive actions critical factors.

The Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use Questionnaire (USE) (78) was used to assess the perceived usefulness, ease of use, ease of learning, and satisfaction with the intervention. The scale includes items such as “It gives me more control over the activities in my life,” “Both occasional and regular users would like it,” and “I easily remember how to use it.” Responses were rated on a 1–7 Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

The Website Engagement Tool (78) was used to measure the level of engagement in the Al-Khaizuran DHI. This included two scores: total amount of time spent on the site, and total number of modules completed by participants. These components are consistent with prior CATCH-IT research on engagement, which included the same variables (43).

Tools translationWith the exception of the BDI-II and DASS tools, which have valid and reliable Arabic versions, all other instruments used in this study were translated into Arabic following the WHO guidelines for translation (79). This process involved three key steps: initial translation, cultural adaptation, and validation. The translation emphasized semantic, technical, and conceptual equivalence to ensure that meanings and cultural relevance were preserved. Key informant interviews and focus groups were conducted to refine the tools further, incorporating feedback from diverse participants to address issues of readability and cultural appropriateness. Back translation was then used to verify the accuracy of the translated versions, and revisions were made accordingly.

Statistical analysisSPSS version 23.0 was used to conduct the analysis. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies while continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviations. Differences in patient-centered outcomes pre and post intervention were tested using repeated Measures ANOVA adjusted for gender and age. Differences in post-interventional patient-centered outcomes per intervention were tested using ANCOVA adjusted for gender and age. Multiple multivariate linear regression models were utilized to detect predictors of behavioral intention to prevent depression. A p-value of less than 0.05 was set for statistical significance. For the univariate analysis, normality was checked and all scores were normally distributed. However, due to the small sample size, non-parametric testing was also used, and it showed the same results as their parametric counterparts.

As per the qualitative data, we utilized the approach outlined by Iloabachie et al. (80) for the analysis. This process involved four members of the research team compiling and evaluating the data to identify recurring themes. Grounded theory methodology was applied, with each team member independently reviewing the material. The team then discussed potential themes, and after thorough deliberation, consensus was reached on the key themes, with the belief that thematic saturation had been achieved. Following this, two team members categorized all comments according to the agreed themes. Any differences in categorization were resolved between the two members until they achieved 85% agreement on the final taxonomy. To ensure objectivity and reduce bias, we implemented several strategies. First, the research team was composed of individuals who had no prior involvement with the CATCH-IT program and who worked independently from the intervention’s developer. Second, both raters maintained diaries throughout the study to monitor and mitigate any potential bias. Finally, to further assess bias in developing the taxonomy, we reviewed the classification system and the comments with one interviewer to confirm that the taxonomy and comment classification aligned with their interview experiences.

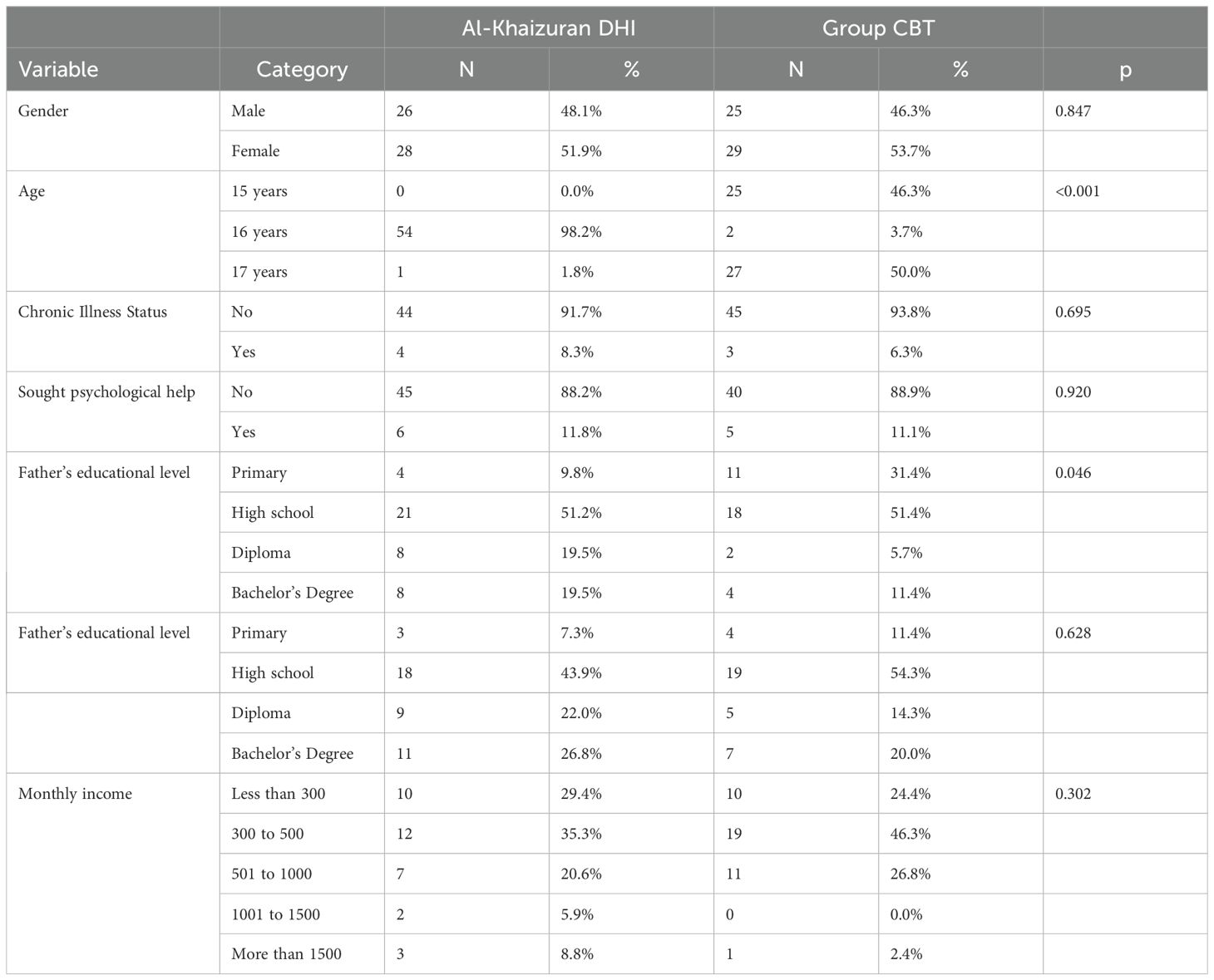

ResultsWe included a total of 109 participants with a mean age of 16.1 ± 0.7 years and male-to-female ratio of 0.78-to-1. The majority of participants did not report chronic illnesses (92.8%) nor sought psychiatric help (88.7%). High school was the highest degree of education for most fathers (50.6%) and mothers (48.1%) of included children. Participants’ characteristics are included in Table 2.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the included sample (n = 117).

Aim 1: evaluate the feasibility and cultural acceptability of Al-Khaizuran DHI among Jordanian adolescents, and compare its acceptability to targeted school-based group CBTBoth qualitative and quantitative data were collected to evaluate the feasibility and cultural acceptability of Al-Khaizuran DHI among Jordanian adolescents. This approach also allowed for a comparison of its acceptability to targeted school-based group CBT. Below are results of the analyses of the semi-structured interviews with participants arranged around two main themes: content and language, and accessibility and engagement.

The content and languageThe content and language used on the website received mixed feedback from the students, highlighting areas of both strength and improvement. Many appreciated the interactive elements, such as being asked to recall personal experiences, and found the exercises and activities, like relaxation techniques, to be highly beneficial. The simplicity and positivity of the website’s ideas were well-received, with students expressing that the content was generally easy to understand and engage with. However, several students noted that the language used was relatively formal, suggesting that a mix of colloquial and formal Arabic would make the content more accessible and relatable.

“I would have preferred the language to be colloquial rather than standard Arabic, as at some points I was listening to boring news!”There was also a recurring concern about the amount of text, with several students reporting a desire for a more personalized approach, where users could access only the sections most relevant to them to reduce the need to sift through extensive text. The audio features of the website were praised for making the content more engaging.

“Hearing the text helped me a lot, without the audio clips that read the text the site would be boring.”Several students appreciated the realism of the stories, noting that they reflected real-life issues and provided useful insights. These students found the narratives impactful, with some even drawing parallels between the stories and their own experiences. However, a few students expressed a desire for more detailed narratives, preferring to have the full context and background to fully grasp the lessons being conveyed.

“The stories were brief, but I prefer to know all the details, even the smallest ones, as they might capture my interest more.”“I liked the stories, and some had a lasting impact that I always remember. I could even relate some of the stories to myself.”Accessibility and engagementThe interviews revealed a wide range of experiences regarding accessibility and engagement with the website. Some students were able to incorporate the site into their daily routines, spending between 15 minutes to an hour per session and finding it beneficial enough to consider making it a regular part of their lives. These students reported using the site consistently for about a week or more, with a few indicating that their engagement would be higher if they had their own devices. One student mentioned using the site for five to seven days, dedicating an hour each day. However, they noted that they are unlikely to continue this routine due to not having access to a personal device. Another student said that they initially used the site daily for two weeks but did not continue due to a lack of motivation, despite benefiting from the sections they completed. Almost all students reported that they wish they could discuss the website content consistently with a mental health professional.

Device accessibility emerged as a significant barrier for several students. Those who did not have a personal device, and instead used a parent’s or sibling’s device, reported discomfort and concerns about privacy, which hindered their engagement with the site. For instance, one student noted that they could only use their mother’s phone, which limited their ability to participate in the site’s activities consistently. Similarly, another student who shared a device with their father mentioned that using the site was not comfortable due to the lack of privacy, which discouraged them from continuing despite recognizing its benefits. These students suggested that their engagement would be higher if they had their own devices.

“I didn’t use the exercises on the site, because the mobile that I enter from on the site is for my mother, so I didn’t have much time““My problem was that I didn’t have my own device to use the site, I was using my parents’ device but this was never comfortable, I didn’t want anyone to read what I was writing on the site.”Time constraints also played a role in how students engaged with the website. Some students with more free time were able to spend extended periods on the site, sometimes using it for over an hour per session. In contrast, those with after-school responsibilities, such as work or family obligations, found it challenging to find time to engage with the site regularly. One student, who worked after school, noted that they were unable to find sufficient time to use the site, which limited their ability to fully benefit from its content. All the students who were interviewed suggested that time be allocated at school to use the site.

“I had a lot of free time that part of it filled the use of the site, I was happy to fill my free time with something useful”“I think it is necessary to allocate appropriate time daily or weekly at school to use the site”The desire for a more modern and interactive design was echoed by several students who found the current layout too rigid and static. They expressed a preference for a more dynamic and engaging interface, comparable to popular social media platforms, which they felt would make the site more appealing and user-friendly.

“If I were to change something, it would be the way the text is presented. I feel like there should be more colors and images.”“The colors used were easy on the eyes. I love the color green; it makes me feel optimistic.”Overall, while the website’s usability was generally well-received, there was a clear demand for enhancements in its design and interactivity to better meet the expectations of its young users.

Quantitative dataBased on the questionnaire assessing usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use, participants shared several notable observations about Al-Khaizuran DHI. Around half of the participants felt the program helped them be effective (52.9%) and empowered them (54.0%). Similar proportions found it simple to use (54%), flexible (51.0%), consistent (46.0%), quick to learn (57.1%), intuitive (55.1%), and pleasant to use (52.0%). Additionally, 51.0% reported being satisfied with the program, and 51.0% indicated they would recommend it to others. However, a considerable number of responses were neutral, categorized as “Neither” (see Table 3). These neutral responses may not necessarily signify dissatisfaction. Further analysis of usage data revealed that many participants who selected neutral responses had completed less than 60% of the program.

留言 (0)