Increased milk and meat production in ruminant animals, such as goats, is associated with the depletion of feed resources and methane (CH4) emissions, highlighting the importance of enhancing productivity while mitigating environmental impacts (Xue et al., 2022).

Feed efficiency (FE) is closely associated with microbial fermentation, which depends on high-efficient microbial groups, including bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi (Li and Guan, 2017; Løvendahl et al., 2018).

These microbial groups work together to break down and transform the ingested animal diet into microbial protein (MP) and volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which fulfill the host animal’s energy and protein needs (Firkins and Yu, 2015). Also, microbial fermentation generates hydrogen (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) that are used, besides other substrates, such as acetic and formic acid and methanol, as substrates to produce methane by rumen archaea (Difford et al., 2018). Methane represents a loss in the animal’s gross energy intake and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions (Rabee et al., 2022).

Understanding the relationship between the rumen microbiome and FE can improve current breeding programs by facilitating the selection of highly efficient animals (Xue et al., 2022).

Additionally, recent studies demonstrated the association between the host genome and the rumen microbial community in cattle (Li et al., 2019). Therefore, effective strategies to improve FE and reduce methane emissions in livestock should focus on both animal genomes and rumen microbiomes (Difford et al., 2018).

Animals with higher FE exhibited lower methane emissions, a lower relative abundance of Methanobrevibacter, and higher levels of Candidatus Methanomethylophilus archeae and propionic acid-producing bacteria (Tapio et al., 2017; Bharanidharan et al., 2018; McLoughlin et al., 2020). Previous studies on rumen microbiota indicated that the bacterial community in goats was affiliated mainly with the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, and the dominant genera were Prevotella, Butyrivibrio, and Ruminococcus (Giger-Reverdin et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2022), whereas the gut archaeal community was dominated by the genera Methanobrevibacter and Methanosphaera (Luo et al., 2022).

Feed constitutes the largest expense in livestock production, making selective breeding a key strategy to reduce costs (Singh et al., 2022; Khanal et al., 2023). Thus, identifying genetically superior animals with high FE has become integral to breeding programs. The recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies have helped breeders collect adjunct information about the genetic potentiality of their animals to be included in genomic selection (Weigel, 2017). The best animals (i.e., animals that eat less feed while maintaining similar production to their herd mates) are then selected for breeding to transmit their genes of high FE to the next generations (Khanal et al., 2023). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) use hundreds of thousands of genetic markers, typically single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), that spread out across the entire genome to identify genetic markers for the trait of interest, which supports genomic selection in livestock (Desire et al., 2018; Moreira et al., 2019; Taussat et al., 2020; Barría et al., 2021; Uffelmann et al., 2021; Khanal et al., 2023).

Zaraibi (also known as Egyptian Nubian) and Shami (also known as Damascus) goats are the most important goat breeds in Egypt due to their high potential for fertility and milk production under harsh conditions (Eid et al., 2020; Almasri et al., 2023). Therefore, animals of the two breeds were involved in genetic improvement programs for exotic breeds in several countries (Güney et al., 2006; Tatar et al., 2021). The rumen microbiome and host genome of goat breeds in arid regions received less attention. Furthermore, few studies explored the association between the rumen microbiome, host genome, and FE in ruminant animals. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between FE, rumen microbiota, and host genome in Shami and Zaraibi goat breeds.

Materials and methods Ethics statementAll animal procedures included in the current study were approved by the Animal Breeding Ethics Committee at the Desert Research Center (DRC) in Egypt (reference number: AB/NO2022) and the Research Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Alexandria, Egypt (Reference: Alex. Agri. 082305307). All methods and protocols in this study comply with the ARRIVE 2.00 guidelines. The experiment did not include animal euthanasia, and all animals were released to the goat herd after the end of the experiment.

Animals and samplingThe experiment was conducted at the Agriculture Research Station, Animal Production Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Sakha, Kafr El Sheikh, Egypt. A total of 20 lactating goats were selected to represent both breeds, ensuring sufficient statistical power for comparative analysis. The animals comprised Shami goats (SH) with an average body weight of 40.6 ± 1.39 kg (n = 10) and Zaraibi goats (ZA) with an average body weight of 25.3 ± 1.57 kg (n = 10). The experiment lasted 45 days, with a 15-day adaptation period followed by 30 days of data collection. The adaptation period aimed to adapt the animals to individual housing conditions and feeding systems. All the animals used in this study were the offspring from the Sakha Agriculture Research Station goat herd in Kafr El Sheikh, Egypt. The body weight of the animals was recorded at the beginning of the experiment, and the animals were housed individually and had free access to drinking water. All animals in both groups received the same diet throughout the experiment: fresh Egyptian clover (Trifolium alexandrinum) ad libitum and commercial concentrates (2.5% of live weight per head/day). The quantities of offered and refused clover and concentrates feed mixture were estimated daily for each goat throughout the experiment. Subsequently, dry matter intake (DMI) was calculated as the difference between the offered and refused feed. After 20 days, approximately 200 mL of rumen fluid sample was collected from each doe via a stomach tube before morning feeding. The rumen fluid samples were filtered through a two-layer cheesecloth. The pH of rumen samples was measured using a digital pH meter (WPA CD70, ADWA, Szeged, Hungary). Then, the samples were separated into two portions, which were frozen at −20°C for DNA extraction and to analyze rumen ammonia (NH3-N) and volatile fatty acids (VFA). Milk yield was measured individually on days 20, 35, and 45 using twice-daily hand milking, morning and evening. Approximately 100 mL of representative milk samples were collected to conduct milk chemical composition. At the end of the experiment, all animals were released back to the goat herd without euthanasia.

FE calculationThe gross FE was calculated using the equation FE = milk production (kg/d) divided by DMI (kg/d). Fat-corrected milk for 3.5% fat content was calculated using the formula: milk yield (MY) 3.5% = (0.432 + 0.1625 × % milk fat) × milk yield, kg/d (Sklan et al., 1992). Subsequently, adjusted FE was calculated using the formula: FE = 3.5% fat-corrected milk yield (kg)/dry matter intake (kg). Milk net energy (Milk NE) was calculated using the equation described in National Research Council (NRC) (2001): Milk NE (Mcal of NE_L/d) = Milk Production x (0.0929 * Fat % + 0.0563 * Protein +0.0395 * Lactose %). Finally, FE for lactation was calculated using the formula: Mcal/kg = Milk NE (Mcal /d) / DMI /d.

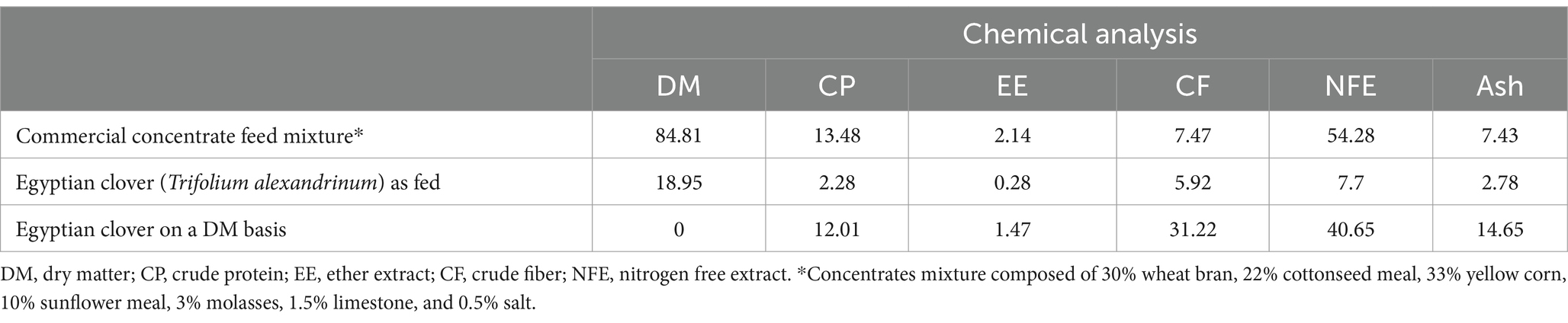

Chemical analysesDiets: Fresh Egyptian clover, concentrate feed mixture, and refused Egyptian clover were analyzed (replicate for every sample”) according to the method of AOAC (1997) to measure dry matter (DM, method 930.15), crude protein (CP, method 954.01), crude fiber (CF, method 962.09), ether extract (EE, method 920.39), and ash contents (method 942.05; Table 1). Nitrogen-free extract (NFE) was estimated by the difference from the sum of the protein, fat, ash, and crude fiber content.

Table 1. Chemical composition of the experimental diets.

Chemical composition of milk: The percentage of milk protein, fat, lactose, and total solid, in addition to somatic cell count (SCC, cells/ml), were analyzed using a MilkoScan (130 A/SN. Foss Electric, Hilleroed, Denmark) using three aliquots (6 mL/aliquot) for each sample. Before the testing, milk samples were heated to 40°C and homogenized by vortexing for 20 s.

Fatty acids in milk: The total lipid content of milk was extracted using the Folch et al. (1957) method. Briefly, 2 mL of milk sample were transferred into 15 mL screw cap tubes. Then, 6 mL of a mixture containing chloroform and methanol in a ratio of 2:1 were added to the tubes, followed by vortexing for 3 min. Next, 2 mL of deionized water was added to the tubes and vortexed for 3 min. The tubes were then centrifuged for 30 min at 5000xg. The lower phase containing the extracted lipids was transferred to clean tubes and allowed to dry at room temperature. To methylate the fatty acids, sodium methoxide (2 M) was used following the method suggested by Kramer et al. (1997). The extracted lipids dissolved in 1 mL of hexane were mixed with 200 μL of sodium methoxide and vortexed. The mixture was kept for 10 min at room temperature, and then the clear top layer was transferred to gas chromatography (GC) vials. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) were analyzed using GC with a mass spectrometer detector (Trac 1,300, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, United States) and a TG-5MS Zebron capillary column. The FAME compounds were identified using AMDIS software based on their retention times matching the NIST library database.

Rumen fermentation: For volatile fatty acid (VFA) and ammonia analysis, 1 mL of rumen fluid samples were transferred into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. The samples were then acidified by 200 μL of meta-phosphoric acid 25% (w/v) and stored at −20°C for later analysis. Upon thawing, samples were centrifuged at 30,000 × g (15,000 rpm, JA-17 rotor) for 20 min, and then the supernatant was used for VFA and ammonia determination. A 750 μL of supernatant was transferred to GC vials for VFA analysis by injecting 1 μL into gas chromatography (TRACE 1300, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, United States) using a capillary column (TR-FFAP 30 m × 0.53 mmI D × 0.5 μm). A standard with known concentrations of VFA was used for calibration. The other 250 μL of supernatant was used for ammonia determination colorimetrically using an ammonia assay kit (Biodiagnostic Company, Dokki, Giza, Egypt). The predicted methane was determined using the following equation: Methane yield = 316/propionate +4.4, according to Williams et al. (2019).

Rumen microbial communityDNA extraction and PCR amplification: Total microbial DNA was extracted from 500 μL of rumen sample. Briefly, the sample was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, DNA was extracted from the precipitated solid material using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The quantity and quality of DNA were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis and a Nanodrop spectrophotometer 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, United States). The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with the primers 515F and 926R using the following PCR conditions: 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 50°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The rumen archaeal community was studied using primers Ar915aF and Ar1386R, and the PCR amplification was conducted under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 55°C for 15 s, 72°C for 5 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR amplicons were purified and sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq system.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysesThe generated paired-end sequence reads were analyzed using the DADA2 pipeline in the R platform (Callahan et al., 2016). The fastq files of sequence reads were demultiplexed, and their quality was evaluated. Then, the sequences were filtered, trimmed, and dereplicated, followed by merging read 1 and read 2 together to get denoised sequences. Generate denoised amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), and chimeric ASVs were then removed. Taxonomic assignment of ASVs was performed using the “assign taxonomy” and “addSpecies” functions, as well as the SILVA reference database (version 138). Alpha diversity metrics were measured, including observed ASVs, Chao1, Shannon diversity, and inverse Simpson diversity indices.

Additionally, the beta diversity of the bacterial and archaeal communities was determined as principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, and figures were created using the phyloseq and ggplot R packages. The differences in alpha diversity indices, relative abundances of bacterial and archaeal phyla and dominant bacterial and archaeal genera, feed intake, rumen fermentation parameters, milk yield and composition, and FE were examined using an unpaired t-test at p < 0.05. Function prediction of microbial communities associated with Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goat breeds was conducted based on the 16S rRNA data using PICRUSt2 (Douglas et al., 2020) based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. The false discovery rate (FDR) method was used for multiple-comparison correction, and p-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Blood sampling and genotypingFor animal genotyping, blood samples were collected using vacutainer tubes containing EDTA from each animal’s jugular vein. Samples were directly transferred in an icebox to the Molecular Genetics laboratory at DRC for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted using a Puregen Core Genomic DNA extraction from blood (Qiagen®, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantity and quality of extracted DNA were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, United States). High-quality DNA samples (≥ 50 ng/μL) were used for genotyping at the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology, Dummerstorf, Germany, using the Illumina®Inc. Goat_IGGC_65K_v2 Infinium HD array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). SNP locations reported in this paper are based on the latest goat genome version of Capra hircus available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (ARS1, NCBI). The genotyping BeadChip contained 59,727 SNPs, evenly distributed throughout the entire genome. Genotype calling was performed using GenomeStudio software (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The quality control of genotyped SNPs was performed using PLINK v1.9 software (Chang et al., 2015), with the following filtering criteria: (i) SNPs showing significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) were excluded (p < 10−6); (ii) SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.01 were removed; (iii) markers with a genotype call rate < 99% and individuals with a call rate < 90% were filtered out. Additionally, SNPs mapped to unknown chromosomal positions or duplicate positions on the same chromosome were excluded to ensure data integrity for subsequent analyses.

Genome-wide association analysisGenetic variance explained by markers. The single-step GBLUP implemented in the BLUPF90 family (Legarra et al., 2014) was used to estimate the SNP effects from genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) of genotyped animals using the postGSf90 software of the BLUPF90 package (Aguilar et al., 2010). SNP effects were calculated as: û = DZ’ [ZDZ’]−1 âg, where û is the vector of the SNP effect; D is the diagonal matrix for weighting factors of the SNP effect; Z is the matrix of genotypes, and âg is the vector of breeding values predicted for genotyped animals. The variance explained by each SNP was calculated as σ2 = û2 2p(1 − p), where û is the SNP effect described above, and p is the allele frequency of the SNP (Zhang et al., 2010). The percentage of genetic variance explained by a window segment of 5 adjacent SNPs was calculated as: (Var (ai)) / (σ2a) x100%, where ai is the genetic value of the i-th region that consists of 5 adjacent SNPs, and σ2a is the total genetic variance (Wang et al., 2014). Manhattan plots of minus log10 of SNP p-values versus chromosomal location were drawn using the qqman package in R (Turner, 2018).

Functional annotation, candidate genes, and gene enrichment analysisFor genome windows above the threshold (i.e., explained >0.1% of the total genetic variance), functional annotation of genes was obtained from BioMart at the Ensembl Genome Browser (Kinsella et al., 2011). Gene functions and protein domains were identified by the UniProt OMIA (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Animals) and the GeneCards databases (Safran et al., 2021). The genes that overlapped with the identified genomic interval of the candidate genome were considered candidate genes for FE in goats and were enriched using ShinyGO v. 0.77 (Ge et al., 2020) software. The analysis was based on gene ontology (GO; Ashburner et al., 2000) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Kanehisa et al., 2023) against the goat gene set ontologies. The program’s default parameters were applied, and the results were adjusted to a false discovery rate (FDR < 0.05).

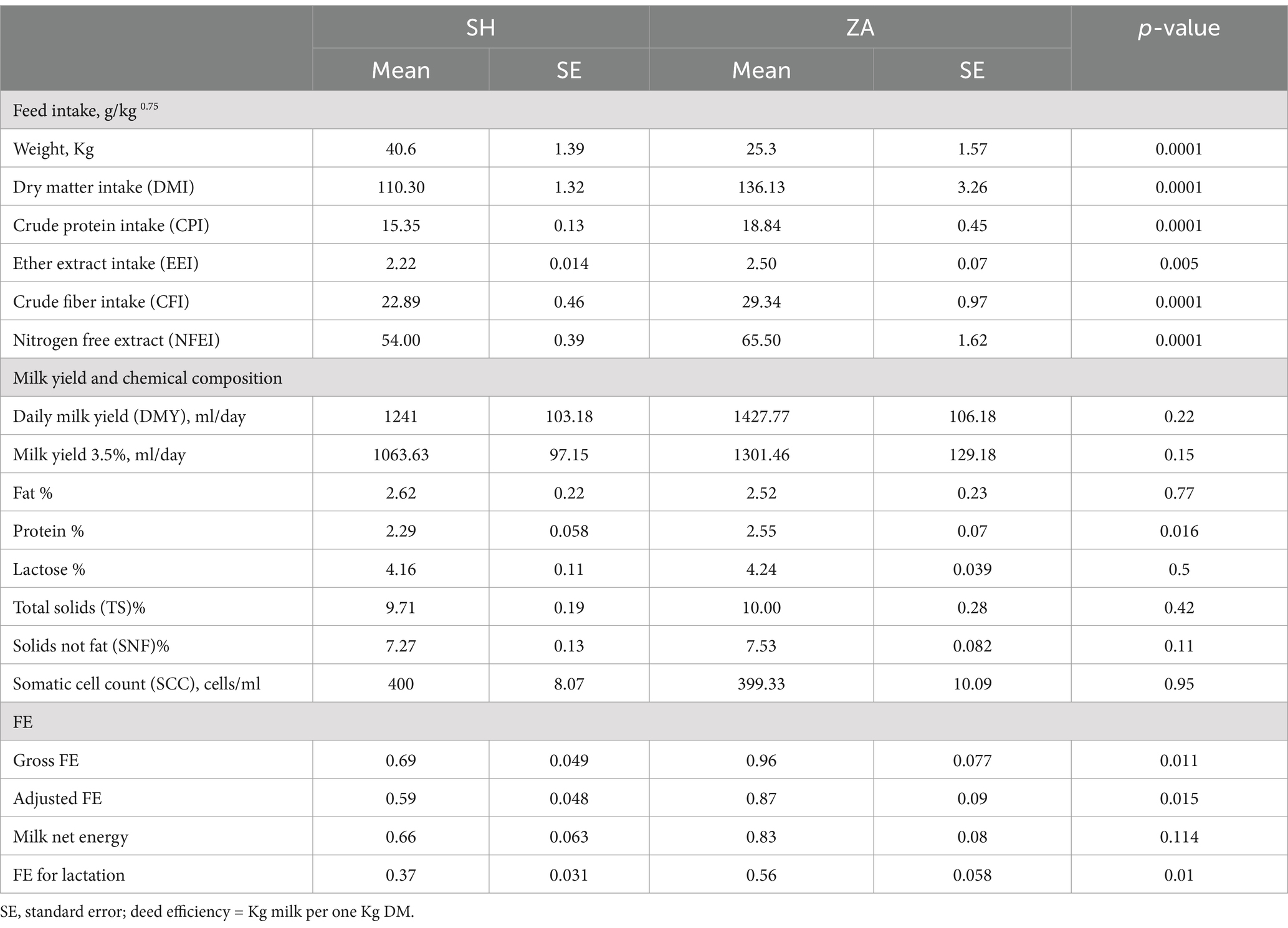

ResultsFeed intake. Animals in this study were fed the same diet, which consisted of a concentrate feed mixture and fresh Egyptian clover. ZA goats exhibited significantly lower body weight compared to the SH goats (p < 0.05; Table 2). Goat breed significantly affected feed intake (g/kg^0.75, metabolic body weight), with ZA goats consuming more DM, CP, CF, EE, and NFE than the SH goats (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Feed intake (g/kg 0.75), milk yield and composition, and FE parameters in SH and ZA goat breeds.

Daily milk yield (DMY), chemical composition, and FE. The estimated average DMY was higher in the ZA goats than in the SH goats. However, the difference was not significant (p > 0.05), and 3.5% of fat-corrected milk followed the same trend (Table 2). Furthermore, the percentages of milk fat, lactose, total solids (TS), solids not fat (SNF), and somatic cell count (SCC) did not exhibit significant differences between the studied goat breeds, but milk protein was higher in the ZA goats (2.55%) than in the SH goats (2.29%; p < 0.05). Based on milk yield and DMI, ZA goats exhibited greater FE expressed as gross FE and adjusted FE (Table 2; p < 0.05). Moreover, milk net energy was higher in the ZA goats without significant difference, and FE for lactation was higher in the ZA goats compared to the SH goats (p < 0.05; Table 2).

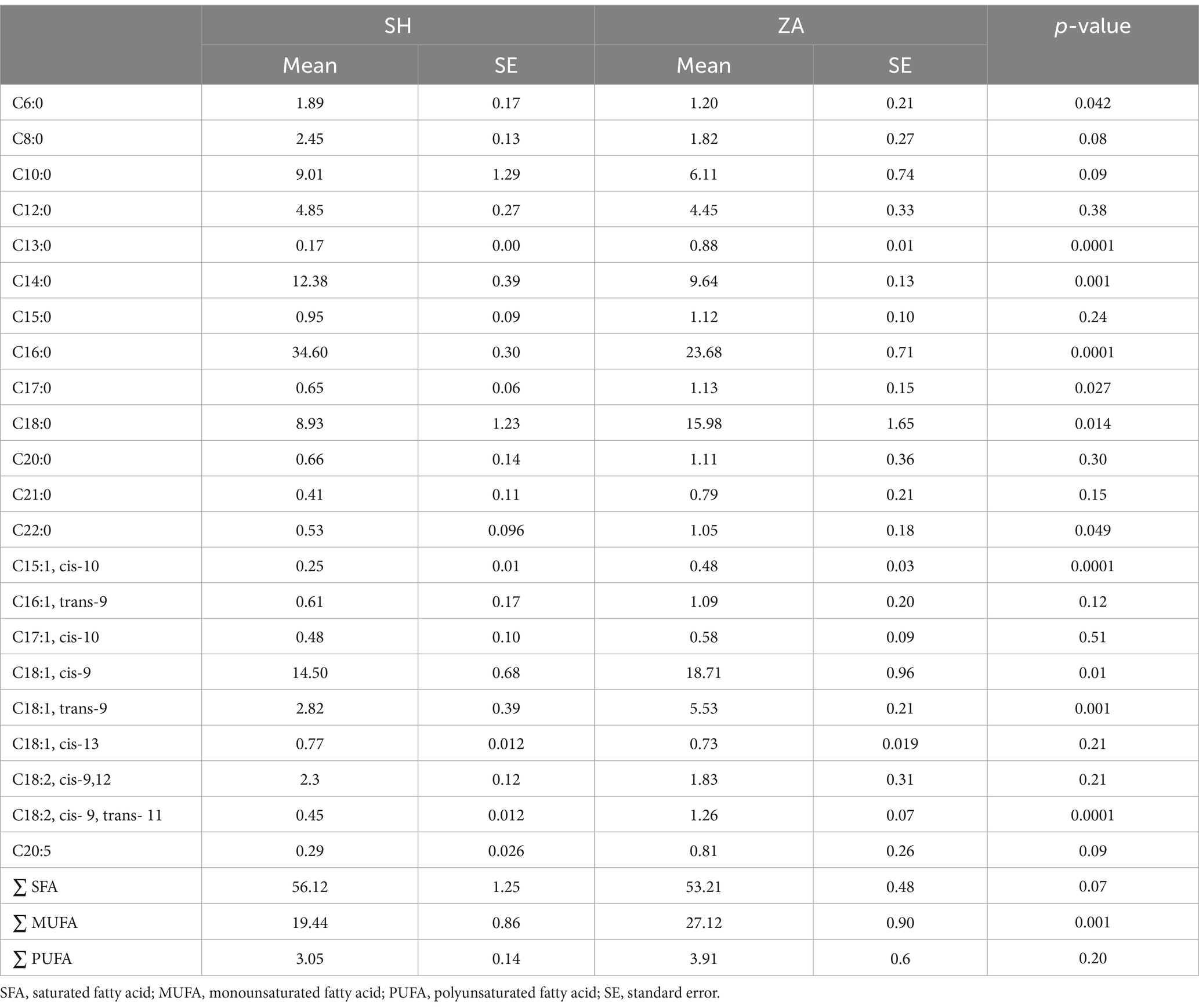

Milk fatty acids: The most abundant fatty acids identified were palmitic (C16:0), oleic (C18:1-cis), stearic (C18:0), myristic (C14:0), capric (C10:0), lauric (C12:0), and linoleic (C18:2-cis-9.12; Table 3). The proportions of certain fatty acids in milk were influenced by the breed of goat. The SH goats exhibited higher percentages of caproic (C6:0), myristic (C14:0), palmitic (C16:0), and total saturated fatty acids (∑ SFA; p < 0.05). In contrast, the ZA goats exhibited higher percentages of tridecylic (C13:0), heptadecanoic (C17:0), stearic (C18:0), behenic (C22:0), pentadecenoic (C15:1, cis-10), oleic (C18:1, cis-9), elaidic (C18:1, trans-9), rumelenic (C18:2, cis 9, trans 11), mono-unsaturated fatty acids (∑ MUFA), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (∑ PUFA; p < 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3. Milk fatty acids (%) in Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goat breeds.

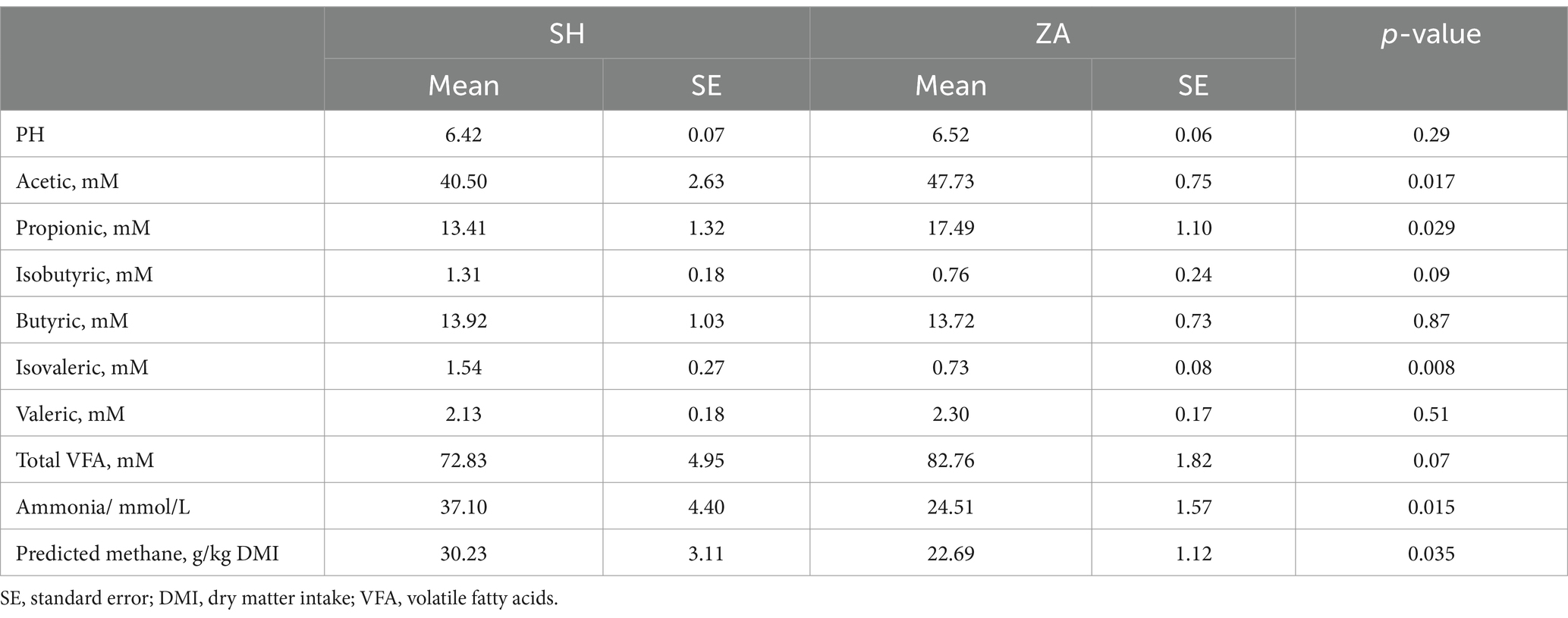

Rumen fermentation: The concentrations of acetic, propionic, and total VFA were higher in the ZA goats (p < 0.05; Table 4). Additionally, rumen ammonia, isovaleric, and predicted methane were higher in the SH goats (p < 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4. Rumen fermentation parameters in Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goat breeds.

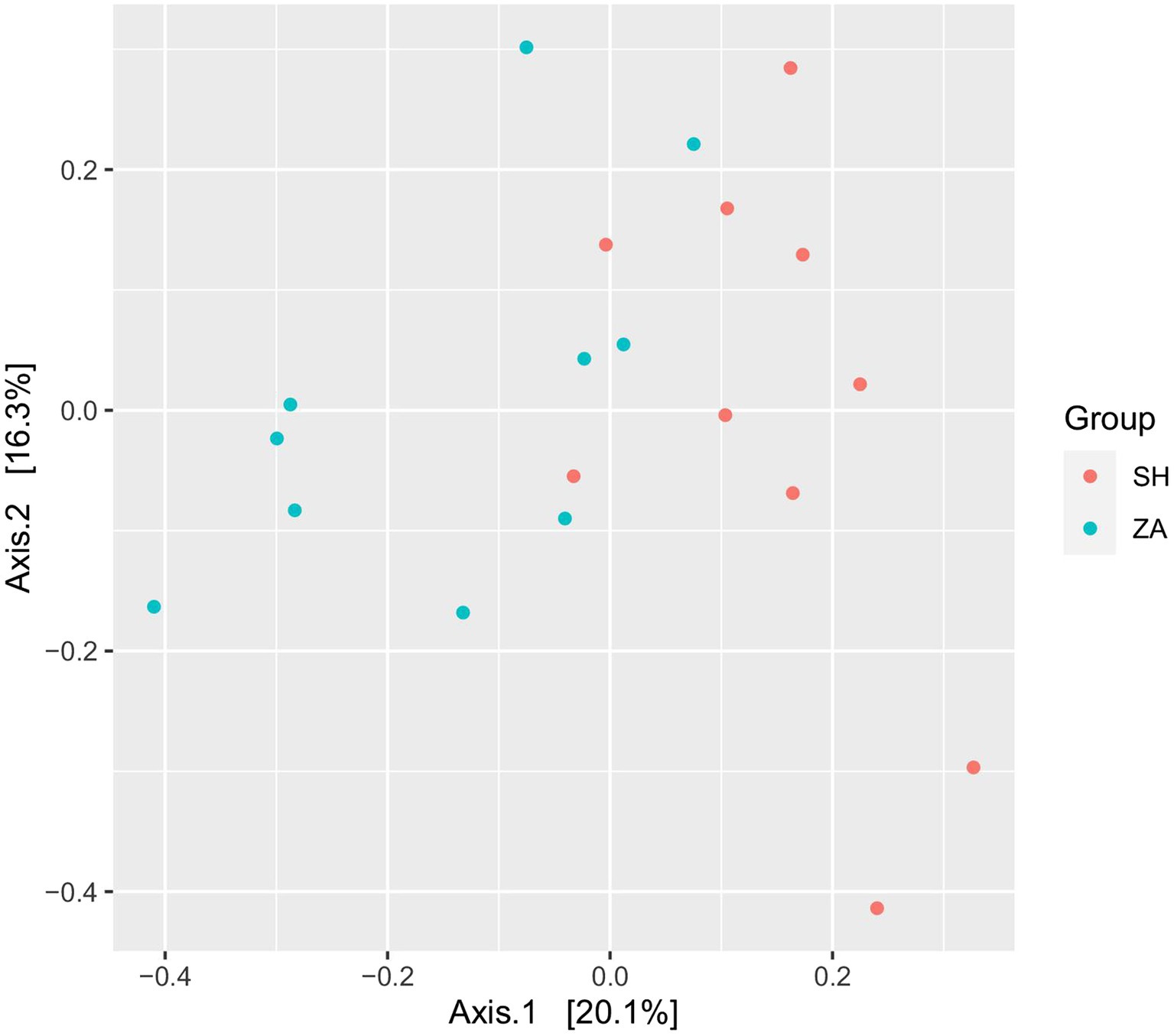

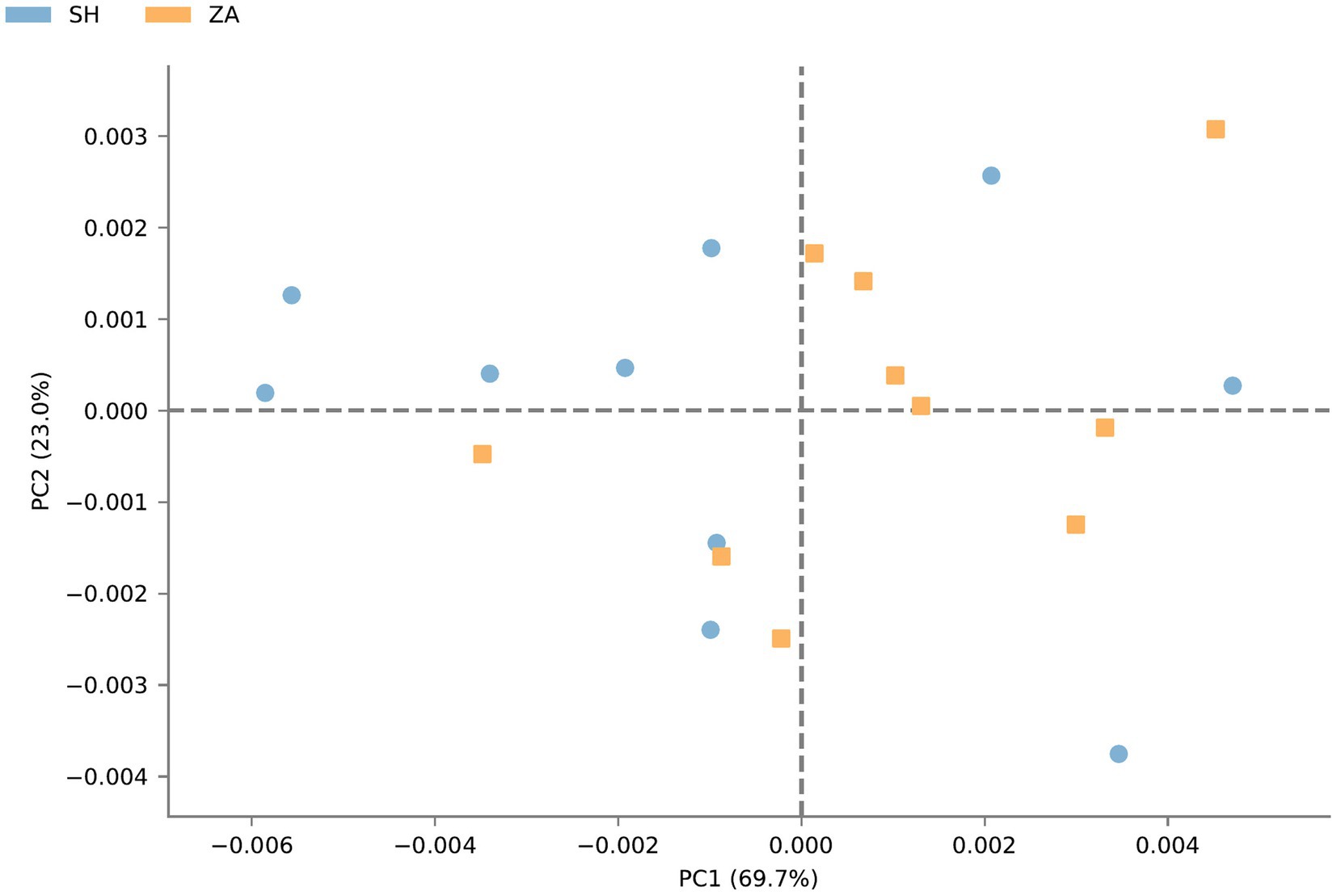

Microbial communityDiversity of bacterial community: The total high-quality non-chimeric reads in the SH and ZA goats were 570,677 and 666,870, respectively, and the difference in the average reads number between the goat groups was not significant (p > 0.05; Table 5). Alpha diversity was calculated as observed ASVs, Chao1, Shannon, and inverse Simpson. (Table 5) showed that the ZA goat group had numerically lower alpha diversity metrics without significant differences (p > 0.05). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis distance was conducted to show the similarity between microbial communities (Figure 1). The results revealed that bacterial communities were clustered separately based on the goat breeds.

Table 5. Alpha diversity indexes of rumen bacteria and relative abundances (%) of bacterial phyla in the rumen of SH and ZA goat breeds.

Figure 1. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of bacterial community. PCoA of rumen bacteria in lactating goats based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. The analysis was conducted between two goats’ breeds: red circles for Shami breed (SH), blue circles for Zaraibi breed (ZA).

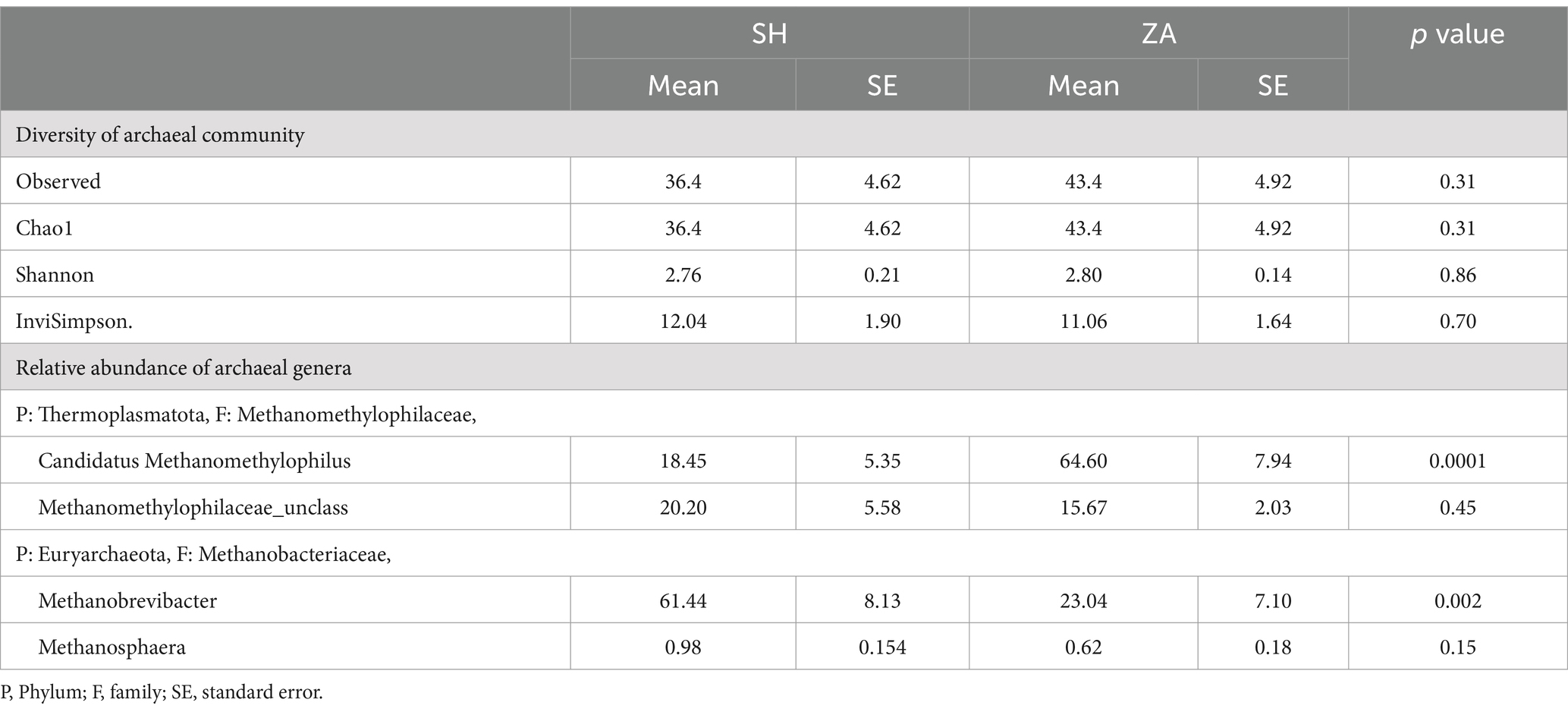

Structure of bacterial community: At the phylum level, the bacterial community in the rumen of goats was affiliated with eight bacterial phyla, including Bacteroidota, Cyanobacteria, Desulfobacterota, Fibrobacterota, Firmicutes, Planctomycetota, Spirochaetota, and Verrucomicrobiota, which were shared between all rumen samples (Table 5). In addition, one bacterial phylum, Synergistota, was observed only in the SH goats. The goat breed affected the relative abundance of bacterial groups (Table 5). Bacteroidota and Firmicutes were the most abundant bacterial phyla, representing more than 98% of the bacterial community. The Bacteroidota phylum dominated the bacterial community and accounted for 85.06 and 87.54% in the SH and ZA goats, respectively. This phylum was classified mainly into the families Prevotellaceae, Rikenellaceae, Bacteroidales RF16 group, Bacteroidales p-251-o5, Bacteroidales F082, Muribaculaceae, and Bacteroidales BS11 gut group (Table 6). Except for the family Prevotellaceae, other families showed higher relative abundance in the SH goats. Family Prevotellaceae represented the most abundant family and accounted for 60.38% in the SH goats and 66.57% in the ZA goats with a significant difference (p < 0.05); this family was classified mainly into two genera, Prevotella and Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, that were higher in the ZA goats. Family Rikenellaceae was dominated by the Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group, which was higher in the SH goats (Table 6).

Table 6. Relative abundances (%) of dominant bacterial families (F) and genera (G) in the rumen of Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goat breeds.

Phylum Firmicutes accounted for 14.77% of the SH goats and 11.03% of the ZA goats, with a significant difference (p < 0.05; Table 5). This phylum was classified mainly into four families, Ruminococcaceae, Oscillospiraceae, Christensenellaceae, and Lachnospiraceae, which were higher in the SH goats (p < 0.05; Table 6). Family Oscillospiraceae was affiliated mainly with the genus NK4A214 group, family Christensenellaceae was affiliated mainly with the genus Christensenellaceae R-7 group, and family Lachnospiraceae was affiliated mainly with the Lachnospiraceae NK3A20 group that was higher in the ZA goats (p < 0.05) in addition to the genus Butyrivibrio that was higher in the SH goats (Table 6). Phylum Fibrobacterota and Spirochaetota were more abundant in the ZA goats compared to the SH goats (p < 0.05; Table 5).

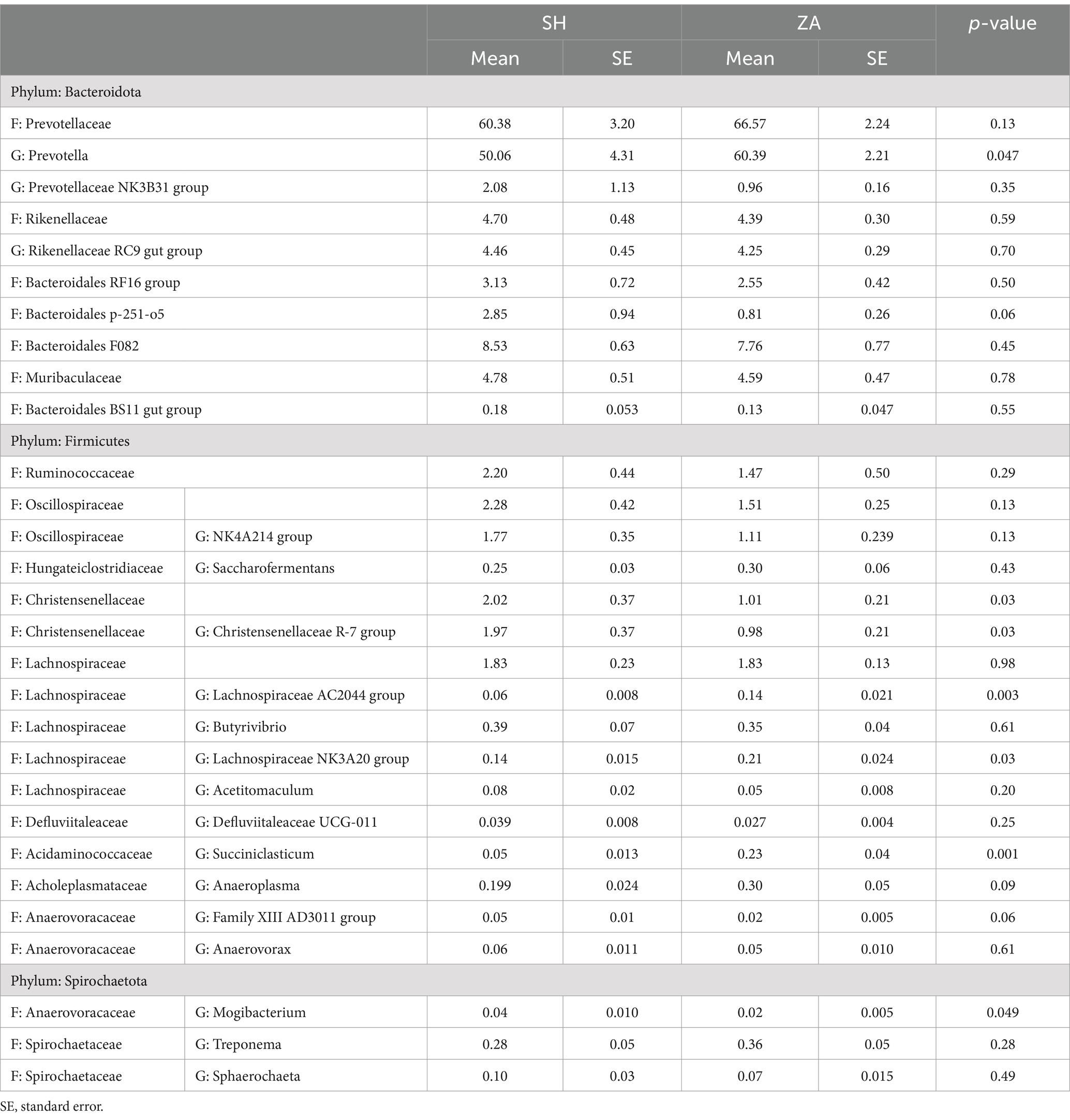

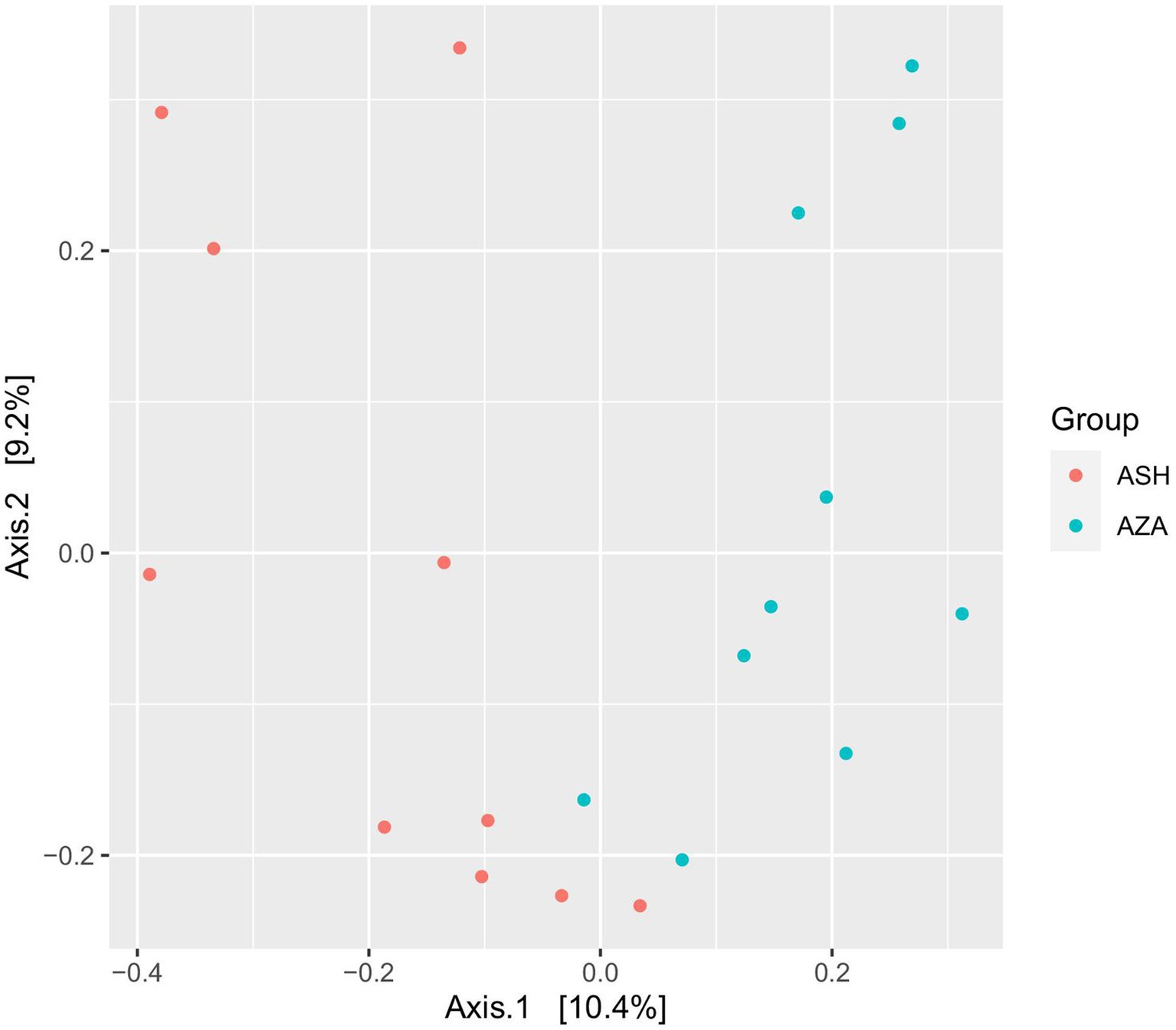

Diversity of archaeal community: After data processing and the chimeras were removed, a total of 40,313 remained in group SH, and 61,061 reads remained in the ZA goats without significant difference (p > 0.05; Table 7). Alpha diversity, including observed ASVs, Chao1, Shannon, and Invisimpsone, was similar between the goat breeds, and the ZA goats showed numerically higher observed ASVs, Chao1, and Shannon, and the SH goats exhibited higher Invisimpsone (Table 7; p > 0.05). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis of archaeal community across the goat breeds demonstrated that the samples were clustered based on the animal breeds (Figure 2).

Table 7. Alpha diversity indexes of rumen archaea and relative abundances (%) of archaeal genera in the rumen of Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goat breeds.

Figure 2. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of archaeal community. The analysis was conducted between two goat breeds: red circles for the Shami breed (ASH) and blue circles for the Zaraibi breed (ZA).

Structure of archaeal community: The taxonomic analysis of the archaeal community revealed that the ASVs were assigned to two phyla, Thermoplasmatota, which was further classified to the family Methanomethylophilaceae, and phylum Euryarchaeota was affiliated with the family Methanobacteriaceae (Table 7). Goat breed affected the archaeal community, and the family Methanomethylophilaceae had two genera, Candidatus Methanomethylophilus, that accounted for 18.45% in group Shami goats (ASH) and 64.60% in Zaraibi goats (AZA) group with a significant difference (p < 0.05), and unclassified Methanomethylophilaceae that was higher in the SH goats compared to AZA. The family Methanobacteriaceae was further categorized into two genera. Methanobrevibacter constituted 61.44% of the archaeal community in the SH goats and 23.04% in the AZA group, showing a significant difference (p < 0.05). Additionally, the genus Methanosphaera was more prevalent in the SH goats compared to AZA (Table 7).

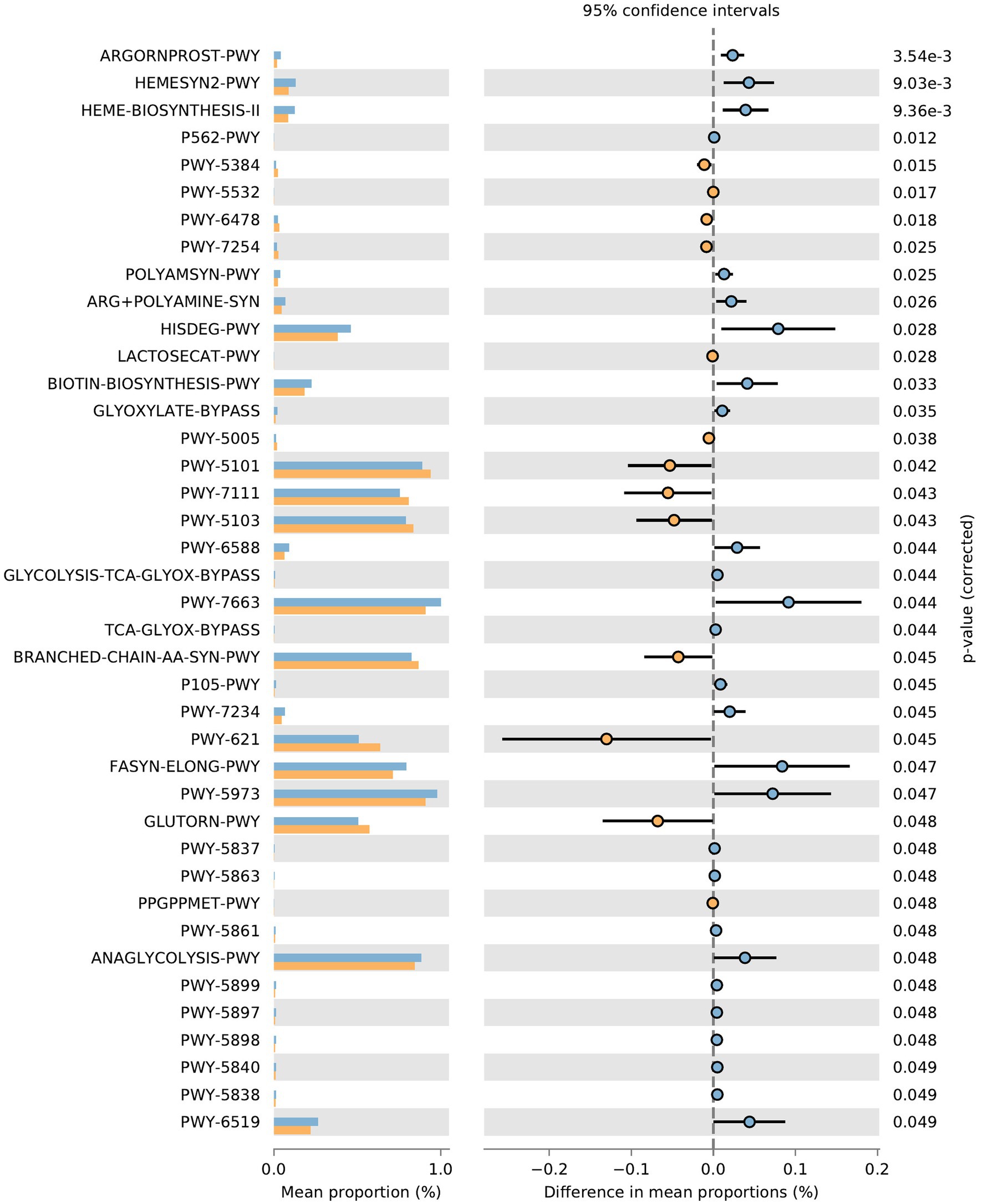

Function prediction of microbial community: The metabolic pathways of rumen microbial communities in Shami (SH) and Zaraibi (ZA) goats were performed using PICRUSt2. Principal components analysis (PCA) of PICRUSt2 function prediction was generated using the relative abundance of metabolic pathways (Figure 3), which revealed that samples were clustered based on animal breeds. The samples of the SH goats revealed significantly higher (q < 0.05) relative abundances of metabolic pathways related to heme biosynthesis-II, L-arginine degradation (ARGORNPROST-PWY), P562-PWY, polyamine biosynthesis I (POLYAMSYN-PWY), ARG + POLYAMINE-SYN, L-histidine degradation I (HISDEG-PWY), biotin biosynthesis-PWY, the glyoxylate cycle (GLYOXYLATE-BYPASS), pyruvate fermentation to acetone (PWY-6588), the glyoxylate cycle and TCA cycle (GLYCOLYSIS-TCA-GLYOX-BYPASS), anaerobic gondoate biosynthesis (PWY-7663), coenzyme B biosynthesis (TCA-GLYOX-BYPASS), and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle IV (2-oxoglutarate decarboxylase; P105-PWY; Figure 4). Additionally, the samples of group ZA revealed significantly higher (q < 0.05) relative abundances of metabolic pathways related to ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, sulfur metabolism, lactose and galactose degradation (LACTOSECAT-PWY), amino acid metabolism (BRANCHED-CHAIN-AA-SYN-PWY), L-ornithine biosynthesis I (GLUTORN-PWY), glycolysis III (ANAGLYCOLYSIS-PWY), the sucrose degradation pathway (PWY-5384), nucleoside and nucleotide degradation (PWY-5532), GDP-d-glycero-alpha-d-manno-heptose biosynthesis (PWY-6478), and the tricarboxylic acid cycle citric acid cycle (PWY-7254; Figure 4).

Figure 3. Principal components analysis of PICRUSt2 functional prediction of microbial communities in the rumen of Shami and Zaraibi goat breeds. Orange squares refer to ZA samples, and blue circles refer to SH’s samples.

Figure 4. Effect of animal species on the relative abundances of metabolic pathways of rumen microbial communities in the rumen of SH and ZA goat breeds. Orange pars refer to ZA’s samples, and blue pars refer to SH’s samples.

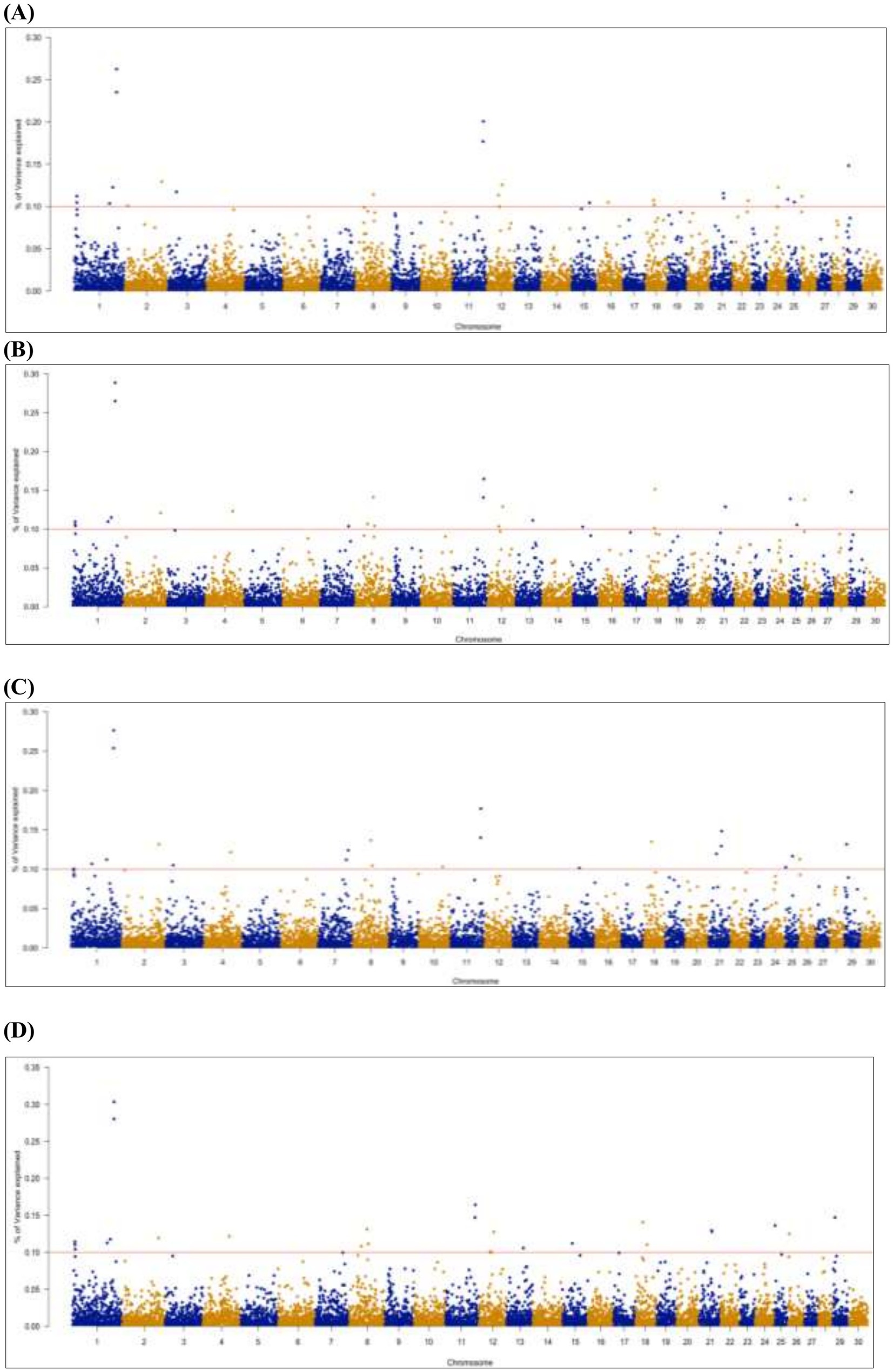

Genetic variance explained by markers: A significant genome window was considered to contribute to the genetic variance of FE traits if it accounted for more than 0.1%. A total of 26 genome windows, each explaining >0.1% of the total genetic variance explained by all windows, with a total of 2.32% of genetic variance (Figure 5). These windows were located on chromosomes 1 (6, 110, and 132 Mb), 2 (9 and 116 Mb), 3 (24 Mb), 7 (88 and 94 Mb), 8 (60 Mb), 10 (76 Mb), 11 (94 and 95 Mb), 12 (47 Mb), 13 (53 Mb), 15 (31 Mb), 18 (21, 23, 25, and 36 Mb), 21 (25 and 41 Mb), 22 (49 Mb), 24 (33 Mb), 25 (1 and 22 Mb), and 26 (3 Mb; Table 8; Supplementary file 1).

Figure 5. Manhattan plots of genome-wide association results for gross FE (A), adjusted FE (B), milk net efficiency (C), and FE for lactation (D) in Egyptian goats. Each dot represents a genome window. The scale of the y-axis represents the significance of the percentage of genetic variance explained by the genome window, and chromosomes are displayed on the x-axis.

Table 8. Percentages of variance explained by genome windows and the annotated genes for FE traits in goats.

Gene enrichment analysis: The gene enrichment analysis identified 26 significant (q < 0.05) biological pathways using a list of the identified candidate genes in the current study (Supplementary Excel file S1). The identified candidate genes were significantly enriched in biological pathways related to the regulation of the transport process of many cellular components such as ions, lipids, organic substances, amino acids, and the general transporter activities mechanism (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of biological pathways for the list of candidate genes resulted from genome-wide association analysis for FE in Egyptian goats. False discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

DiscussionFE represents an animal’s capacity to convert feed components into products such as meat and milk through rumen microbial fermentation. This efficiency directly impacts the profitability of livestock production enterprises (Fischer et al., 2022). Therefore, investigating the relationship between the rumen microbiome, animal genotype, and FE is crucial for genetic improvement programs in livestock species comprising goats. In the current study, goats’ diets consisted of a mixture of feed concentrates and fresh clover, which is a high-quality roughage. Estimates of milk yield and feed intake values were in agreement with the values reported by Ghoneem and El-Tanany (2023). On the other hand, milk yield in the current study (Table 2) was higher than those obtained by Alsheikh (2013) and Kholif et al. (2020) for Shami and Zaribi goat breeds. To the best of our knowledge, no studies compared the FE, feed intake, and milk yield between the SH and ZA goats under the same husbandry conditions. However, the studies conducted by Ghoneem and El-Tanany (2023) and Kholif et al. (2020) reported estimates of FE in the SH and ZA goats similar to our study.

ZA goats achieved higher FE (0.96 kg milk/kg DM) than the SH goats (0.69; p < 0.05), likely due to their superior feed utilization and adaptation to the arid conditions of southern Egypt, their region of origin (Alsheikh, 2013). Similarly, Knights and Garcia (1997) reviewed Zaraibi goats as producing higher milk than Shami goats.

Variations in feed intake, milk yield, and composition (Tables 2, 3), and FE between breeds were reported in different ruminant species (Knights and Garcia, 1997; Paz et al., 2016; Currò et al., 2019; Gustavsson et al., 2014; Niero et al., 2023). Bharanidharan et al. (2018) reported that high-efficiency dairy cows showed higher feed intake and higher milk yield. Our results showed that ZA goats exhibited higher levels of milk protein and unsaturated fatty acids (∑ PUFA), which is consistent with the higher abundance of Prevotella observed. The breed-specific differences in milk fatty acid profiles observed in this study align with previous findings in goats and sheep (Idamokoro et al., 2019). This could be attributed to variations between animal species and breeds in metabolic pathways of lipids in mammary glands and rumen microorganisms (Conte et al., 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to understand the differences in milk fat profiles in different livestock breeds.

Zhang et al. (2023) and Sasson et al. (2017) explained that host genome and rumen microbiome impact milk protein, which could be altered due to a higher abundance of rumen bacteria: Prevotella, Bacteroidales, Clostridiales, Flavefaciens, and Ruminococcus. Additionally, the proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) is affected mainly by rumen microorganisms through rumen biohydrogenation (Shingfield et al., 2010; Huws et al., 2011). In this regard, Hu et al. (2020) identified a positive correlation between the higher Prevotella and higher unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) in yaks, as Prevotella play a vital role in energy harvesting in the rumen, and it might provide precursors for UFA synthesis, which demonstrates the higher UFA in ZA compared to the SH goats in this study. A similar conclusion was obtained by Huws et al. (2011), who studied the bacteria that play a predominant role in ruminal biohydrogenation.

Rumen ecosystem and FEThe rumen bacterial community in goats was dominated by the phyla Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Spirochaetota, and Fibrobacterota (Table 5), aligning with findings from previous studies on goats (Giger-Reverdin et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2022). The Firmicutes phylum was higher in the SH goats with lower FE, which was also reported in low-efficiency beef cattle by Brooke et al. (2019).

Host genetics significantly influence the rumen microbiome, with approximately 35% of microbial taxa being heritable (Li et al., 2019). This implies that the difference in the microbial communities between the two goat breeds in the current study is expected. In this context, our PCoA analysis (Figure 1) showed that the bacterial communities in SH and ZA breeds were distinct, which agrees with the findings of Paz et al. (2016) in Holstein and Jersey breeds. Similar results were obtained by Mani et al. (2021) in the rumen of Damara and Meatmaster sheep breeds in South Africa. In the current study, ZA showed numerically low alpha bacterial diversity compared to the SH goats (p > 0.05; Table 5), which is similar to other findings in dairy cows (Shabat et al., 2016).

The variation in the composition of rumen microbiota results in changes in rumen fermentation efficiency, wherever the ZA goats had lower ammonia than the SH goats (24.51 vs. 37.10 mmol/L, p < 0.05). Furthermore, the ZA goats showed higher total VFA than the SH goats (82.76 vs. 72.83 mM, p < 0.05) as well as higher acetic and propionic (Table 4; p < 0.05). VFAs represent the main energy source of the host animal (Paz et al., 2016). Nitrogen and carbohydrate metabolism are the main microbial functions in the rumen (Xue et al., 2022). Higher VFA production in ZA was associated with higher fiber-degrading bacteria and higher carbohydrate metabolism pathways (Table 4; Figure 4), which agrees with Tapio et al. (2017) and Xue et al. (2022), indicating that Zaraibi goats have higher efficiency in carbohydrate metabolism. This finding is supported by higher relative abundances of Fibrobacters, Prevotellaceae, and Lachnospiraceae in the rumen of the ZA goats. These bacterial groups have essential roles in complex carbohydrates and protein metabolism (Thoetkiattikul et al., 2013; Paz et al., 2016; Neumann et al., 2018). Xue et al. (2022) reported that pathways related to carbohydrate metabolism could be used as prediction markers to differentiate efficient and inefficient rumen microbiomes or animals, which helps the future selection of high-efficiency animals. These findings were supported by Wang et al. (2023), who reported higher carbohydrate metabolism pathways in goats with higher growth performance. On the other hand, the ZA goats showed higher relative abundances of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) pathways. The increase in the relative abundance of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) pathways could refer to a higher concentration of BCAA in the rumen. Zhang H. L. et al. (2013) reported that BCAA stimulates fiber-degrading microorganisms and VFA production.

Furthermore, the increment in acetic acid production was accompanied by an increment in the PWY-7254 pathway (tricarboxylic acid cycle citric acid cycle), which is involved in the synthesis of precursors of acetic acid (De Sales-Millán et al., 2024). Group ZA showed lower rumen ammonia and higher relative abundances of pathways related to nitrogen metabolism, which could indicate the efficient use of nitrogen in microbial protein synthesis and the decline in nitrogen loss (Firkins et al., 2007). Higher synthesis of microbial protein increases the protein supply to the host animals Zhang H. L. et al. (2013). Furthermore, the ZA goats showed higher sulfur metabolism, which is linked to lower methane production (Wu et al., 2021), as sulfate-reducing bacteria are able to compete with methanogens for H2 in the rumen, which inhibits the methanogenesis (Zhao and Zhao, 2022).

Genus Prevotella is a major player in ruminal metabolism and predominated the rumen microbiome in several ruminant species (Betancur-Murillo et al., 2022). A higher relative abundance of genus Prevotella was associated with the highly efficient breed (i.e., ZA; Tables 2, 6). This finding is supported by Brooke et al. (2019), who reported that the Prevotella is a microbial marker identifying cattle with higher FE. Genus Prevotella includes members that utilize a wide range of substrates, such as hemicellulose and protein (Matsui et al., 2000). Myer et al. (2015) found a higher relative abundance of Prevotella in the gut of steers with high daily gain and intake. De Vadder et al. (2016) indicated that the genus Prevotella produces succinate, which is the precursor to propionate. The propionate synthesis uses hydrogen molecules, reducing its availability for methane production by methanogenic archaea (Betancur-Murillo et al., 2022). Thus, Prevotella has the potential to be used as an anti-methanogenic agent.

The members of the family Lachnospiraceae have fibrolytic and cellulolytic activities and were associated with higher milk production in Holstein cows (Thoetkiattikul et al., 2013; Paz et al., 2016). In this study, the candidate genus Lachnospiraceae NK3A20 was higher in the ZA goats; this genus was reported to produce butyric acid that promotes the development of the rumen (Huang et al., 202

留言 (0)