Cerebrovascular diseases rank as the second leading cause of death, following heart diseases (Heron, 2007; Zhang et al., 2021a). Stroke is characterized by a sudden disturbance in blood flow, leading to mild or severe neurological dysfunction (The World Health Organization, 1988; World Health Organization, 2004). According to reports, 15 million people suffer from stroke annually, with 5.5 million succumbing to the disease (Banerjee et al., 2005). Stroke rates are increasing, particularly in developing countries, posing a significant societal burden (Zhang et al., 2021b; Shen et al., 2020).

Strokes can be classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic (Xu et al., 2018a; Wang et al., 2022; Xu and Zhong, 2013). They result from an interruption in the blood supply to brain tissues, leading to reduced oxygen and nutrients. Extensive research has been conducted on the pathological mechanisms and various therapeutic drugs for stroke, including studies on cellular apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, brain edema, and cell death (Yi et al., 2013; Han et al., 2004). Currently, no drugs are specifically effective in treating stroke.

The apelin protein and its receptor APJ are extensively distributed in the brain, primarily located in oligodendrocytes and neurons (Gregory et al., 2004; Lee et al., 1993). Growing evidence suggests that apelin and its receptor APJ play crucial roles in protecting neural cells post-stroke (Bhalala et al., 2013; Tatemoto et al., 1998). Therefore, targeting the apelin/APJ system offers neuroprotection for stroke patients. This review aims to highlight the latest developments in the study of the apelin/APJ system’s functions and therapeutic potential in stroke patients.

2 Introduction of the apelin/APJ system2.1 ApelinThe apelin gene expresses a 77-amino acid preproprotein, which is cleaved into several active peptides (Habata et al., 1999; Hosoya et al., 2000; Reaux et al., 2001). The full-length apelin, originating from bovine stomach extracts, consists of 36 amino acids. The presence of apelin-36 was further confirmed in bovine colostrum, and a 13-amino acid peptide (apelin-13) was also identified.

In the peptide, the N-terminus is modified by pyroglutamate, a post-translational modification that renders the protein resistant to enzymatic cleavage. Several potential proteolytic sites on apelin-36 suggest the existence of other endogenous apelin isoforms, such as apelin-19, apelin-17, apelin-16, and apelin-12, all of which can activate the APJ receptor (Kawamata et al., 2001; Tatemoto et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2005; Szokodi et al., 2002; Ronkainen et al., 2007). However, peptides containing fewer than 12 amino acids are inactive. In contrast to preproprotein, shorter forms of apelin exhibit higher binding affinity and greater activity, with pyroglutamated apelin-13 being the most potent.

Under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) upregulates apelin protein levels (Wang et al., 2006). During lactation, apelin synthesis is upregulated in breast tissue via upstream stimulatory factor-1 (Boucher et al., 2005). In fasting states, adipocyte apelin gene expression decreases, while refeeding stimulates its expression, possibly through changes in insulin and counter-regulatory hormone concentrations (Wei et al., 2005; Reaux-Le Goazigo et al., 2004). Furthermore, apelin expression in hypothalamic neurons is increased through the regulation of arginine vasopressin (Vickers et al., 2002). Post-translational processing of apelin is less understood, but angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) may be involved (O'Dowd et al., 1993). ACE2 efficiently hydrolyzes apelin-13 and apelin-36, although its physiological significance remains unknown.

2.2 The APJ receptorThe human APJ receptor, first reported by O'Dowd et al., is a G protein-coupled receptor with a 377-amino acid sequence located on chromosome 11 (Chng et al., 2013). In 1998, Tatemoto et al. identified apelin as the endogenous ligand of APJ (Habata et al., 1999). It wasn’t until 2013 that two groups independently discovered Elabela as another APJ ligand (Pauli et al., 2014; O'Carroll et al., 2006). The genetic regulation of APJ is complex, with a TATA-less promoter region playing a role in APJ gene expression. Physiological stimuli such as stress, salt loading, and water deprivation induce APJ synthesis (Pugh and Tjian, 1991). Several genes with TATA-less promoters are activated by Sp1 (Japp and Newby, 2008), which is also crucial for APJ promoter activation. Other factors influencing promoter activity include estrogen, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein, and glucocorticoids (Pugh and Tjian, 1991).

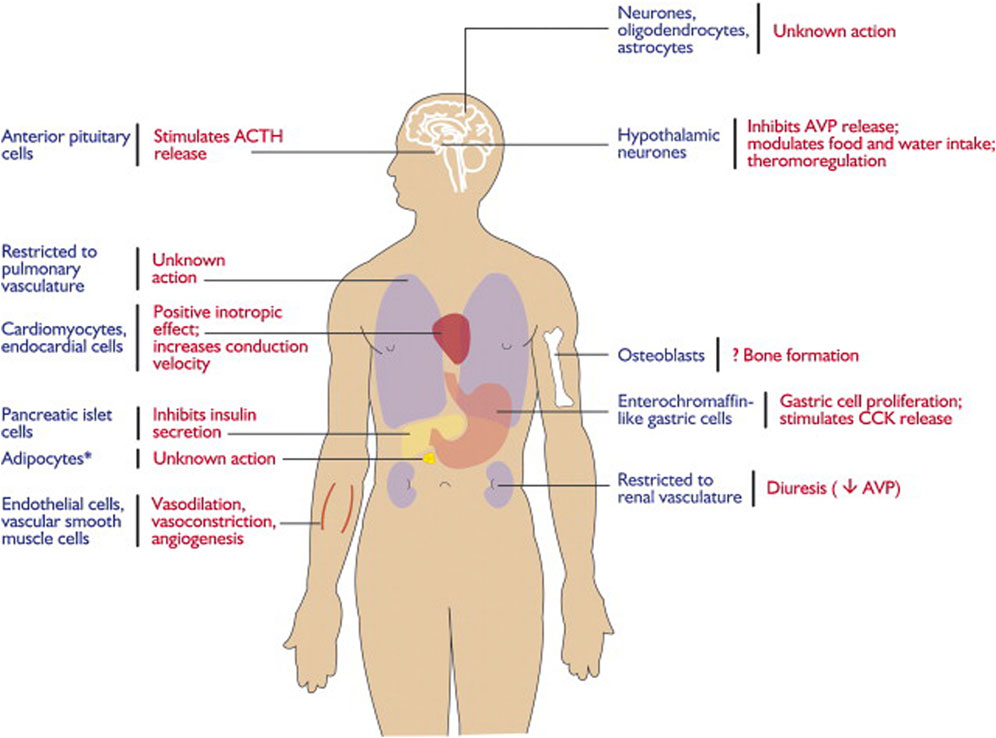

2.3 Distribution of the apelin/APJ system in the CNSThe apelin/APJ system is extensively distributed in the CNS and other tissues (Lee et al., 2000) (Figure 1). In detail, the apelin/APJ system is expressed in neurons of the cerebral cortex, pituitary gland cells, hippocampus, hypothalamus, T-lymphocytes, and pancreatic islet cells. Apelin expression levels are associated with APJ expression.

Figure 1. Expression and physiological functions of the apelin–APJ system. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Chng et al., 2013).

In the CNS, apelin is expressed both centrally and peripherally. Northern blot analysis detected apelin mRNA in the CNS of rats (O'Carroll et al., 2000; Medhurst et al., 2003). The highest mRNA expression of apelin was observed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, pineal gland, spinal cord, and olfactory tubercle of rats (O'Carroll et al., 2000; Reaux et al., 2002) (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical techniques identified apelin-LI in other neural cells, including neurons of the hypothalamus, pons, and medulla oblongata (Kawamata et al., 2001; Kleinz et al., 2005). In humans, apelin expression was first reported in the hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglion, hypothalamus, frontal cortex, and basal forebrain (O'Carroll et al., 2000). Another study localized apelin mRNA in the corpus callosum, spinal cord, substantia nigra, amygdala, and pituitary (Reaux et al., 2002). Apelin-LI is expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum, secretory vesicles, and Golgi complex of endothelial cells, but not in cell organelles of inducible endothelial peptide secretion (Lee et al., 2004).

In the CNS, APJ can be detected in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus, with the highest levels in the hypothalamus (O'Carroll et al., 2000; Medhurst et al., 2003) (Figure 3). Immunocytochemical detection showed that apelin receptors are also expressed in the nuclei of several neuron types, including hypothalamic and thalamic nuclei (Reaux et al., 2002). APJ expressed in human embryonic kidney cells shares similar characteristics with that expressed in rat hypothalamic and cerebellar nuclei (Choe et al., 2000).

Studies on cells expressing APJ in the CNS revealed its presence in neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, but not in macrophages or microglia. Immunocytochemical analysis using an antibody against the apelin receptor confirmed its distribution in the human brain (Masri et al., 2006). APJ-LI was detected only in human pyramidal and cerebellar neurons in culture.

2.4 Biochemistry: intracellular signaling mechanismsStudies have shown that apelin inhibits the production of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP, suggesting that APJ is coupled with inhibitory G proteins (Gi) (Habata et al., 1999). Additionally, apelin can activate extracellular-regulated kinases (ERKs) in a Ras-independent manner (Masri et al., 2002) and activate p70S6 kinase in an ERK- and Akt-dependent manner (Neves et al., 2002). Pertussis toxin inhibits these signaling cascades, indicating that they are supported by APJ-Gi coupling. However, pertussis toxin does not completely suppress apelin’s inotropic effect (Ronkainen et al., 2007) but can activate phospholipase C and protein kinase C, which are activated by Gq proteins (Zhou et al., 2003). Therefore, it is possible that APJ receptors couple with both Gq and Gi proteins. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) can be hydrolyzed by phospholipase C to produce inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) (Zhou et al., 2003), demonstrating that apelin can increase intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Masri et al., 2006). Notably, several apelin-mediated signaling cascades are reduced in sensitization following activation (Masri et al., 2002), likely due to the internal positioning of APJ receptors (Eggena et al., 1979). Different sizes of apelin fragments lead to different durations of receptor internalization, correlated with varying patterns of desensitization (Masri et al., 2002; Eggena et al., 1979). Finally, APJ receptors are also localized to the nucleus (Choe et al., 2000), suggesting they can regulate transcription in addition to activating intracellular cascades (Tang et al., 2021).

3 Oxidative stress in the CNS3.1 Characteristics of oxidative stress in the CNSOxidative stress causes significant damage to organs under ischemic conditions, including the heart, liver, kidneys, and especially the brain (Andrianova et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2016; Ikeda and Miyahara, 2003; Frank, 2006). Anatomical, physiological, and functional factors make the brain particularly susceptible to oxidative injury. Human brains consume 20% of the body’s oxygen due to their high metabolic rate, although they account for only 2% of body weight. This higher oxygen availability results in increased ROS production (Gu et al., 2011). The brain’s dependence on glymphatic waste disposal, modest antioxidant defenses, excitotoxic and auto-oxidizable neurotransmitters, polyunsaturated fatty acids prone to peroxidation, limited regenerative capacity, redox-active metal burden, and calcium load make it sensitive to ROS.

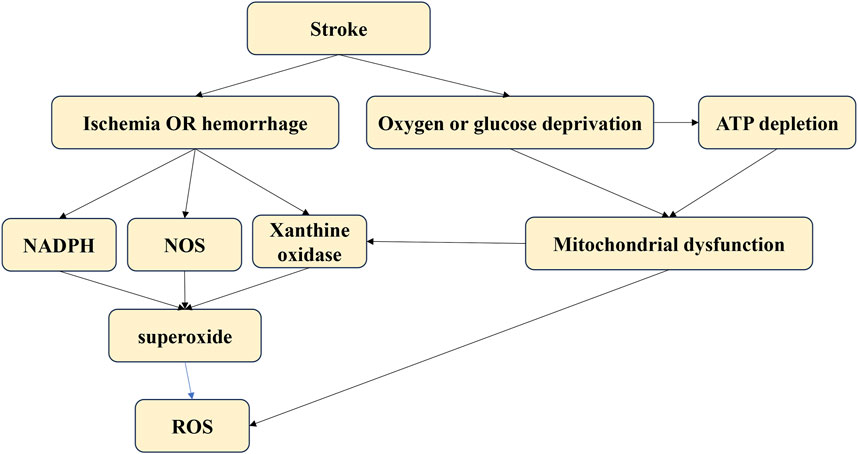

Oxidative stress-related neurofunctional damage may result from various cellular pathophysiological processes within neural cells. The oxidative stress vulnerability of neurons differs biochemically. Psychological stress may compromise antioxidant enzyme function by disrupting the oxidant-antioxidant balance in the brain, depleting glutathione and increasing oxidative stress. When glutamate toxicity occurs simultaneously with mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and calcium overload, it leads to brain damage, impaired neural cell communication, and ultimately neuro-dysfunction. Controlling ROS levels, either by quenching pro-oxidants or enhancing antioxidant defense, is crucial for the CNS. This review provides a biologically plausible explanation of how oxidative damage might contribute to psychiatric symptoms [Figure 4].

Figure 4. The different sources of oxidative stress.

3.2 Signal pathways of ROS in the brainThe mechanisms by which ROS induce brain injuries remain unclear. However, ROS have been demonstrated to cause various cellular pathologies, including blood-brain barrier disruption, neuronal apoptosis, and neuroinflammation (Makino et al., 1996). Evidence suggests that N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor glutamate toxicity and glucocorticoid receptor signaling are involved (Okamoto et al., 1999; Tanaka et al., 1999; Albrecht et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2011; Sorce and Krause, 2009). Neurodegenerative diseases such as cerebrovascular disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease have been linked to increased brain oxidative damage (Kamata et al., 2005).

Oxidative stress is believed to damage macromolecules by activating particular signaling pathways in cells, altering gene expression, and leading to cell death (Finkel, 2000; Meng et al., 2002; Hu and Wieloch, 1994). The mechanisms linking oxidative stress signals to cellular responses remain unclear, but several proteins play important roles, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs: JNK, ERK1/2, ERK5, p38MAPK) (Kuan et al., 2003; Suzaki et al., 2002; Dunah et al., 2002), Sp1 (Susin et al., 1999), oxidoreductase apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) (Vahsen et al., 2004; Chalovich et al., 2006), transcription factors such as cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) (Zaman et al., 1999; Van Der Heide et al., 2004), and Forkhead (FOXO) (Brunet et al., 2004; Essers et al., 2004; Orellana-Urzúa et al., 2020).

4 The functions of the apelin/APJ system in stroke4.1 Pathological mechanisms of strokeStrokes result from an interrupted blood supply to brain tissues, leading to reduced oxygen and nutrients. The lack of blood supply causes a rapid increase in ROS production immediately after an acute stroke. These ROS can damage neural cells, leading to further pathological processes such as neuroinflammation, autophagy, neuro-apoptosis, and blood-brain barrier disruption (Rodrigo et al., 2013). The main sources of ROS after a stroke include mitochondria, nitric oxide synthases, NADPH oxidase, and xanthine oxidase (Wu et al., 2017). Targeting oxidative stress post-stroke is critical to preventing oxidative damage and subsequent pathological processes in stroke patients.

4.2 Expression of apelin/APJ after strokeApelin and APJ expression levels vary at different time points during a stroke (Lv et al., 2013). In one of my previous studies, we found that the endogenous level of apelin-13 increased at 12 h and peaked at 24 h after SAH, while the levels of APJ started to increase at 6 h and peaked at 24 h after SAH (Xu et al., 2019). Various transcription factors, such as ATF4, Sp1, STAT3, and HIF-1α, play crucial roles in regulating the apelin/APJ system (Pugh and Tjian, 1991; He et al., 2015; Han et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Yeh et al., 2011). Cerebral ischemia results in oxygen and glucose deprivation, which is associated with abnormal apelin/APJ signaling (Zhang et al., 2009; Yeh et al., 2011). HIF-1α and Sp1 induce the expression of apelin/APJ after a stroke (Pugh and Tjian, 1991; He et al., 2015; Han et al., 2008). Under ischemic conditions, HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus and activates the transcription and expression of apelin and APJ proteins (Wang et al., 2006; Han et al., 2008). Apelin and APJ expression is induced in neurons during the early stages of ischemia by increased Sp1 via HIF-1α (Woo et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2017). Reperfusion, however, results in the downregulation of the apelin/APJ system. In mice subjected to chronic normobaric hypoxia, APJ expression in the hippocampus is significantly reduced, and apelin-13 can reverse this reduction (Sheng et al., 2012). The apelin/APJ system is also affected by ER stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress (Mei et al., 2015; Morimoto et al., 2007). For example, cerebral I/R injury is mediated by the ER stress response, which is activated during reperfusion but not ischemia (Nakka et al., 2010; Xin et al., 2014; Jeong et al., 2014). Reperfusion may induce apelin expression due to ER stress regulation by ATF4 via the p38 MAPK pathway (Liu et al., 2018). Apelin-12 has been shown to inhibit the JNK and p38MAPK signaling pathways, leading to cell apoptosis in MCAO-induced ischemic mice (Arani Hessari et al., 2022).

Due to the crucial roles of the apelin/APJ system in stroke, targeting it could provide novel treatments for stroke.

4.3 Modulation of oxidative stress by the apelin/APJ system after strokeThe apelin/APJ system is widely studied for its neuroprotective properties, including anti-neuroinflammation, anti-apoptosis, and antioxidative stress. Several studies have reported the neuroprotective effects of the apelin/APJ system in the CNS. However, research on stroke has largely focused on its anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammatory effects, overlooking its antioxidative stress effects (Gholamzadeh et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018b; Xu et al., 2019). This study focuses solely on the antioxidative stress effects of the apelin/APJ system, providing guidance for future research.

The apelin/APJ system inhibits oxidative and nitrative stresses, producing neuroprotective effects. Our previous study showed that the apelin/APJ system exerts significant antioxidative effects by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated oxidative stress via AMPK/TXNIP/NLRP3 signaling pathways (Wu et al., 2015). It also increases superoxide dismutase activity and decreases malondialdehyde (MDA) levels to reduce oxidative stress induced by I/R injury (Duan et al., 2019). Apelin-13 has been shown to significantly decrease ROS and MDA levels while increasing antioxidant protein expression in a dose-dependent manner via the AMPK/GSK-3β/Nrf2 pathway (Khoshnam et al., 2017). The apelin/APJ system may protect cells from oxidative stress-induced death by decreasing ROS production and promoting ROS clearance.

Nitric oxide (NO) exhibits different effects in ischemic stroke: it is neuroprotective when produced by endothelial NOS (eNOS) but mediates oxidative/nitrosative injuries when generated by neuronal NOS (nNOS) (Iadecola et al., 1997; Salcedo et al., 2007). Similarly, apelin has dual effects on vascular function. Activation of the apelin/APJ axis induces peripheral arterial relaxation in a NO- and endothelium-dependent manner (Japp et al., 2008; Modgil et al., 2013). However, in male rats, the apelin/APJ system inhibits NO-induced cerebral artery relaxation by blocking calcium-activated K (BKCa) channels via the PI3K/Akt pathway (Mughal et al., 2018; McKinnie et al., 2017). Further research is needed to determine how apelin affects oxidative/nitrosative stress in ischemic stroke.

5 Potential targets of the apelin/APJ systemAs indicated above, the apelin/APJ system plays a major role in the occurrence and development of several diseases, including strokes. Therefore, targeting the apelin/APJ system can be a promising approach to treating neurological diseases (Brame et al., 2015). Recent studies have identified small molecule agonists and antagonists targeting the apelin/APJ system. For example, an antidiuretic hormone-inducing non-peptide agonist E339-3D6 has been reported to induced vasorelaxation of rat aorta precontracted with noradrenaline and potently inhibited systemic vasopressin release by activating with apelin receptor, which can be a potential target to allow development of a new generation of vasodilator and aquaretic agents (Murza et al., 2014). [20040517]. Additionally, ML233 selectively inhibits AT1 receptors, inducing vasoconstriction via phospholipase C by binding to APJ (Gerbier et al., 2017). These molecules can decrease renin levels generated via the cAMP pathway (Murza et al., 2012). Research on antagonists of APJ receptors is also progressing rapidly. ML221 was the first such antagonist to be developed (Jia et al., 2012); another antagonist, ALX40-4C, has also been identified. The ALX40-4C receptor antagonist, consisting of nine arginine residues, is effective for both APJ and CXCR4 receptors and inhibits intracellular calcium mobilization and receptor internalization in response to ligands, and it can be the potential utility for further elucidation of HIV-1 neuropathogenesis and therapy of HIV-1-induced encephalopathy (Jia et al., 2012). PMID: 12890632 Additionally, some apelin-13-based molecules showed more potent and stable analogs targeted at APJ (Juhl et al., 2016). Cao et al. showed that apelin analogs directly reduced blood pressure by activating the Akt-eNOS/NO pathway. Drugs targeting apelin might help treat inflammation-related diseases associated with oxidative stress. Puerarin has been shown to reduce apelin expression and protect against renal hypertension (Juhl et al., 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001), suggesting its potential in treating oxidative stress-linked blood pressure. To conclude, Apelin/APJ-targeting drugs contribute to pharmacological research and understanding the mechanism of oxidative stress-mediated diseases.

6 ConclusionThe apelin/APJ system is extensively distributed in the brain and plays vital roles in regulating neurological diseases, including stroke. It shows significant neuroprotective effects by suppressing oxidative and nitrative stresses via different signaling pathways. Recent years have seen the discovery of potential drugs targeting APJ and apelin (E339-3D6, ML233, ML221, and ALX40-4C), and pharmacological interactions with Apelin/APJ have become reliable tools for exploring this system’s role in oxidative stress-mediated diseases.

Further in-depth studies on the physiological and pathological effects of the apelin/APJ system and its potential mechanisms will greatly aid clinical prevention and intervention in strokes. The development of drugs targeting the apelin/APJ system will benefit patients and alleviate the pressures on families and society.

This study extensively shows the apelin/APJ system and its antioxidative roles in stroke. However, some limitations should be addressed: 1. This study focuses solely on the antioxidative effects of the apelin/APJ system in stroke, overlooking other physiological roles such as anti-apoptosis and anti-neuroinflammation. Application of this results should be more carefully. 2. Although some clinical trials have been registered (Num. ChiCTR2200060945, ChiCTR2100054712, ChiCTR-OOC-15006043, ChiCTR-ODT-13004019), clinical application of apelin/APJ has not yet been reported. The clinical values of apelin/APJ system should be further explored in future studies. 3. Currently, limited studies focus on the antioxidative effects of the apelin/APJ system in stroke, which remains largely unexplored. Future studies of the apelin/APJ system should include different cellular signaling pathways of oxidative stress, various sources of ROS, and different clinical drugs that can be further explored. 4. The connection of different signaling pathways mediated by apelin/APJ system should be further explored, which can greatly increase the readability and application of apelin/APJ system.

Author contributionsWX: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft. JYa: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. ZT: Writing–review and editing. CL: Writing–review and editing. LG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. HW: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–review and editing. JinZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. JiaZ: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. AS: Investigation, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. JYu: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing.

FundingThe author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001231, 82001299, 82060225, and 82260239); Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ21H090009); Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (no. 2020GXNSFAA297154); and Guangxi Medical University Education and Teaching Reform Project (2020XJGA24).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s noteAll claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbbreviationsCNS, central nervous system; WHO, World Health Organization; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1; ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ERKs, extracellular-regulated kinases; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate; DG, dentate gyrus; ROS, radical oxidative stress; AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; JNK, C-Jun N-terminal kinase; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NO, nitric oxide; BKCa, blocking calcium-activated K.

ReferencesAlbrecht, P., Lewerenz, J., Dittmer, S., Noack, R., Maher, P., and Methner, A. (2010). Mechanisms of oxidative glutamate toxicity: the glutamate/cystine antiporter system xc-as a neuroprotective drug target. CNS and neurological Disord. drug targets 9 (3), 373–382. doi:10.2174/187152710791292567

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andrianova, N. V., Zorov, D. B., and Plotnikov, E. Y. (2020). Targeting inflammation and oxidative stress as a therapy for ischemic kidney injury. Biochem. Biokhimiia 85 (12), 1591–1602. doi:10.1134/S0006297920120111

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arani Hessari, F., Sharifi, M., Yousefifard, M., Gholamzadeh, R., Nazarinia, D., and Aboutaleb, N. (2022). Apelin-13 attenuates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through regulating inflammation and targeting the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 126, 102171. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2022.102171

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Banerjee, T. K., Roy, M. K., and Bhoi, K. K. (2005). Is stroke increasing in India--preventive measures that need to be implemented. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 103 (3), 162.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Boucher, J., Masri, B., Daviaud, D., Gesta, S., Guigné, C., Mazzucotelli, A., et al. (2005). Apelin, a newly identified adipokine up-regulated by insulin and obesity. Endocrinology 146 (4), 1764–1771. doi:10.1210/en.2004-1427

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brame, A. L., Maguire, J. J., Yang, P., Dyson, A., Torella, R., Cheriyan, J., et al. (2015). Design, characterization, and first-in-human study of the vascular actions of a novel biased apelin receptor agonist. Hypertens. (Dallas Tex 1979) 65 (4), 834–840. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05099

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brunet, A., Sweeney, L. B., Sturgill, J. F., Chua, K. F., Greer, P. L., Lin, Y., et al. (2004). Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Sci. (New York NY) 303 (5666), 2011–2015. doi:10.1126/science.1094637

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults--United States, 1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50 (7), 120–125.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Chalovich, E. M., Zhu, J. H., Caltagarone, J., Bowser, R., and Chu, C. T. (2006). Functional repression of cAMP response element in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (26), 17870–17881. doi:10.1074/jbc.M602632200

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chng, S. C., Ho, L., Tian, J., and Reversade, B. (2013). ELABELA: a hormone essential for heart development signals via the apelin receptor. Dev. cell 27 (6), 672–680. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Choe, W., Albright, A., Sulcove, J., Jaffer, S., Hesselgesser, J., Lavi, E., et al. (2000). Functional expression of the seven-transmembrane HIV-1 co-receptor APJ in neural cells. J. Neurovirol 6 (Suppl. 1), S61–S69.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Duan, J., Cui, J., Yang, Z., Guo, C., Cao, J., Xi, M., et al. (2019). Neuroprotective effect of Apelin 13 on ischemic stroke by activating AMPK/GSK-3β/Nrf2 signaling. J. neuroinflammation 16 (1), 24. doi:10.1186/s12974-019-1406-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dunah, A. W., Jeong, H., Griffin, A., Kim, Y. M., Standaert, D. G., Hersch, S. M., et al. (2002). Sp1 and TAFII130 transcriptional activity disrupted in early Huntington's disease. Sci. (New York NY) 296 (5576), 2238–2243. doi:10.1126/science.1072613

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Eggena, P., Zhu, J. H., Clegg, K., and Barrett, J. D. (1979)1993). Nuclear angiotensin receptors induce transcription of renin and angiotensinogen mRNA. Hypertens. Dallas Tex 22 (4), 496–501. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.22.4.496

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Essers, M. A., Weijzen, S., de Vries-Smits, A. M., Saarloos, I., de Ruiter, N. D., Bos, J. L., et al. (2004). FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 23 (24), 4802–4812. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fan, J., Ding, L., Xia, D., Chen, D., Jiang, P., Ge, W., et al. (2017). Amelioration of apelin-13 in chronic normobaric hypoxia-induced anxiety-like behavior is associated with an inhibition of NF-κB in the hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 130, 67–74. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.01.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gerbier, R., Alvear-Perez, R., Margathe, J. F., Flahault, A., Couvineau, P., Gao, J., et al. (2017). Development of original metabolically stable apelin-17 analogs with diuretic and cardiovascular effects. FASEB J. official Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 31 (2), 687–700. doi:10.1096/fj.201600784R

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gholamzadeh, R., Ramezani, F., Tehrani, P. M., and Aboutaleb, N. (2021). Apelin-13 attenuates injury following ischemic stroke by targeting matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), endothelin-B receptor, occludin/claudin-5, and oxidative stress. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 118, 102015. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2021.102015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gregory, R. I., Yan, K. P., Amuthan, G., Chendrimada, T., Doratotaj, B., Cooch, N., et al. (2004). The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432 (7014), 235–240. doi:10.1038/nature03120

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gu, Y., Dee, C. M., and Shen, J. (2011). Interaction of free radicals, matrix metalloproteinases, and caveolin-1 impacts blood-brain barrier permeability. Front. Biosci. Sch. Ed. 3 (4), 1216–1231. doi:10.2741/222

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Habata, Y., Fujii, R., Hosoya, M., Fukusumi, S., Kawamata, Y., Hinuma, S., et al. (1999). Apelin, the natural ligand of the orphan receptor APJ, is abundantly secreted in the colostrum. Biochimica biophysica acta 1452 (1), 25–35. doi:10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00114-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Han, J., Lee, Y., Yeom, K. H., Kim, Y. K., Jin, H., and Kim, V. N. (2004). The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes and Dev. 18 (24), 3016–3027. doi:10.1101/gad.1262504

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Han, S., Wang, G., Qi, X., Englander, E. W., and Greeley, G. H. (2008). Involvement of a Stat3 binding site in inflammation-induced enteric apelin expression. Am. J. physiology Gastrointest. liver physiology 295 (5), G1068–G1078. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.90493.2008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

He, L., Xu, J., Chen, L., and Li, L. (2015). Apelin/APJ signaling in hypoxia-related diseases. Clin. chimica acta; Int. J. Clin. Chem. 451 (Pt B), 191–198. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2015.09.029

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heron, M. (2007). Deaths: leading causes for 2004. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 56 (5), 1–95.

Hosoya, M., Kawamata, Y., Fukusumi, S., Fujii, R., Habata, Y., Hinuma, S., et al. (2000). Molecular and functional characteristics of APJ. Tissue distribution of mRNA and interaction with the endogenous ligand apelin. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (28), 21061–21067. doi:10.1074/jbc.M908417199

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hu, B. R., and Wieloch, T. (1994). Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rat brain following transient cerebral ischemia. J. Neurochem. 62 (4), 1357–1367. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62041357.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Iadecola, C., Zhang, F., Casey, R., Nagayama, M., and Ross, M. E. (1997). Delayed reduction of ischemic brain injury and neurological deficits in mice lacking the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J. Neurosci. official J. Soc. Neurosci. 17 (23), 9157–9164. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09157.1997

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ikeda, S., and Miyahara, Y. (2003). Ischemic heart disease and oxidative stress. Nihon rinsho Jpn. J. Clin. Med. 61 (Suppl. 5), 831–836.

Japp, A. G., Cruden, N. L., Amer, D. A., Li, V. K., Goudie, E. B., Johnston, N. R., et al. (2008). Vascular effects of apelin in vivo in man. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52 (11), 908–913. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Japp, A. G., and Newby, D. E. (2008). The apelin-APJ system in heart failure: pathophysiologic relevance and therapeutic potential. Biochem. Pharmacol. 75 (10), 1882–1892. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2007.12.015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jeong, K., Oh, Y., Kim, S. J., Kim, H., Park, K. C., Kim, S. S., et al. (2014). Apelin is transcriptionally regulated by ER stress-induced ATF4 expression via a p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. Apoptosis Int. J. Program. cell death. 19 (9), 1399–1410. doi:10.1007/s10495-014-1013-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jia, Z. Q., Hou, L., Leger, A., Wu, I., Kudej, A. B., Stefano, J., et al. (2012). Cardiovascular effects of a PEGylated apelin. Peptides 38 (1), 181–188. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2012.09.003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Juhl, C., Els-Heindl, S., Schönauer, R., Redlich, G., Haaf, E., Wunder, F., et al. (2016). Development of potent and metabolically stable APJ ligands with high therapeutic potential. ChemMedChem 11 (21), 2378–2384. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201600307

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kamata, H., Honda, S., Maeda, S., Chang, L., Hirata, H., and Karin, M. (2005). Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 120 (5), 649–661. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.041

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kawamata, Y., Habata, Y., Fukusumi, S., Hosoya, M., Fujii, R., Hinuma, S., et al. (2001). Molecular properties of apelin: tissue distribution and receptor binding. Biochimica biophysica acta 1538 (2-3), 162–171. doi:10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00143-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Khoshnam, S. E., Winlow, W., Farzaneh, M., Farbood, Y., and Moghaddam, H. F. (2017). Pathogenic mechanisms following ischemic stroke. Neurological Sci. official J. Italian Neurological Soc. Italian Soc. Clin. Neurophysiology 38 (7), 1167–1186. doi:10.1007/s10072-017-2938-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kleinz, M. J., Skepper, J. N., and Davenport, A. P. (2005). Immunocytochemical localisation of the apelin receptor, APJ, to human cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Regul. Pept. 126 (3), 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2004.10.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuan, C. Y., Whitmarsh, A. J., Yang, D. D., Liao, G., Schloemer, A. J., Dong, C., et al. (2003). A critical role of neural-specific JNK3 for ischemic apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 (25), 15184–15189. doi:10.1073/pnas.2336254100

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, D. K., Cheng, R., Nguyen, T., Fan, T., Kariyawasam, A. P., Liu, Y., et al. (2000). Characterization of apelin, the ligand for the APJ receptor. J. Neurochem. 74 (1), 34–41. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740034.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, D. K., Lanca, A. J., Cheng, R., Nguyen, T., Ji, X. D., Gobeil, F., et al. (2004). Agonist-independent nuclear localization of the Apelin, angiotensin AT1, and bradykinin B2 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (9), 7901–7908. doi:10.1074/jbc.M306377200

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, D. K., Saldivia, V. R., Nguyen, T., Cheng, R., George, S. R., and O'Dowd, B. F. (2005). Modification of the terminal residue of apelin-13 antagonizes its hypotensive action. Endocrinology 146 (1), 231–236. doi:10.1210/en.2004-0359

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, R. C., Feinbaum, R. L., and Ambros, V. (1993). The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75 (5), 843–854. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, D. R., Hu, W., and Chen, G. Z. (2018). Apelin-12 exerts neuroprotective effect against ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting JNK and P38MAPK signaling pathway in mouse. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22 (12), 3888–3895. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201806_15273

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lv, X. R., Zheng, B., Li, S. Y., Han, A. L., Wang, C., Shi, J. H., et al. (2013). Synthetic retinoid Am80 up-regulates apelin expression by promoting interaction of RARα with KLF5 and Sp1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. J. 456 (1), 35–46. doi:10.1042/BJ20130418

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Makino, Y., Tanaka, H., Dahlman-Wright, K., and Makino, I. (1996). Modulation of glucocorticoid-inducible gene expression by metal ions. Mol. Pharmacol. 49 (4), 612–620.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Masri, B., Lahlou, H., Mazarguil, H., Knibiehler, B., and Audigier, Y. (2002). Apelin (65-77) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases via a PTX-sensitive G protein. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 290 (1), 539–545. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.6230

留言 (0)